Professional Documents

Culture Documents

3 Rules For Hip Towing

Uploaded by

Doug GouldOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

3 Rules For Hip Towing

Uploaded by

Doug GouldCopyright:

Available Formats

TIPS AND TECHNIQUES FOR HIP TOWING

© 2007 Douglas Gould

When I had my own company, and interviewed a prospective captain, applicants would

relate their past experience towing a variety of boats; often boasting about all the miles

they had towed. But I was in Marina Del Rey, where all six thousand boats are in

individual slips; practically every slip with a floating finger on either side, and a

concrete pile at the end of each finger. So, I would explain to my applicant that anybody

can tow a 50’ yacht for fifty miles on a hawser – it’s the last twelve inches that separates

the pros from the hacks. We averaged about 1 dock-dock tow per day, all year long; add

another 500 offshore cases, most of which terminated at a dock. If you consider that each

dock-dock tow involves a maneuver both out of and then into a slip or work dock, you see

that my company was maneuvering over 1000 boats per year into tight quarters. Lets see,

I had the company for over nine years…

Towing on the hip is something that we all have to do, but I have noticed that some

captains are more reluctant than others to do it. I was surprised this spring to see one of

our industry’s more experienced operators attempt to “slingshot” a 54’ full keel sailboat

into a slip. Things got a little tense when it became apparent that the sailboat was heading

towards the wrong slip. Suddenly, the towboat captain was struggling to manage towline,

shift, throttle and helm: basically a four handed job with two hands.

It is my belief that, unless there is an overwhelming reason not to finish a tow on the hip,

every tow that terminates at a dock, slip or mooring should be completed with the

casualty securely hipped up. Attempting to tow a disabled boat on a very short hawser

and then let go at precisely the right

moment requires timing that is too

easily foiled by tide, wind and poor

communications. The “slingshot”

maneuver where you rely on the

skipper of the casualty to steer his

boat the final few yards as it barely

makes headway is a dubious plan at

best, and I shake my head when I see a

towboat trying to check the forward

momentum of a large yacht by pulling

backwards on a towline attached to the

yacht’s bow.

The reluctance to hip up probably

originates from an operator’s past

problems with maneuvering, visibility

and the time it takes to untie. While I

understand these frustrations, most are

easily addressed with a little practice

and planning. One requirement for

successful hip towing will be your mindset; until you believe that being hipped up is the

best way to safely maneuver a boat in tight quarters and into a dock, I don’t think you

will ever really make the commitment to learn to do it well.

As to the time it might take, it is really only a few minutes at most, and if the slingshot

maneuver doesn’t work exactly on the first try, the time to re-group for a second pass will

take more time than just hipping up in the first place would have. From a risk

management standpoint, the two minutes it takes to hip up is time well invested.

I developed a few rules for myself that I passed along to my captains-in-training, and

perhaps you might find these useful guidelines for your captains. As with all rules, you

will discover exceptions.

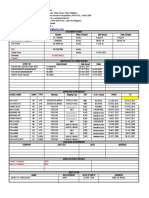

Rule #1: Always plan to be on the “inside” of the final turn. Before I hip up, I make sure I

understand exactly where we will be going. In particular, I want to know what (if any) the

final turn will be. The final turn is the very last turn that the casualty makes as she enters

her slip. If you’re heading to a T head or side tie type of dock, there is no “final turn”,

and obviously you will want to be tied to the side away from the dock. Not only will you

have much better visibility on the inside of the turn, (see diagram #1) but using reverse to

slow down will help to execute the turn at the same time. Single inboard towboats

generally don’t have the luxury of hipping on either side, so my solution was to back up

the last fairway so I ended up on the inside of the final maneuver.

Rule #2: When towing boats equal to or larger than the towboat, always hip up with a

“toe in” attitude. Toe in means that the centerline of your towboat points towards the bow

of the casualty, (see diagram #2) rather than parallel with the casualty’s keel. Without toe

in, you are attempting to steer as if you

had a twin screw with one engine out,

because your power plant’s thrust is still

in line with the casualty’s keel. Directing

your thrust across the keel with toe allows

you to maneuver the entire raft-up more

predictably.

Rule #3: You can’t be too far aft. The

further aft you are, the more leverage your

rudder and prop(s) will have.

Rule #4: Avoid terminating lines

anywhere except on your towboat, i.e.

don’t knot off on the causality’s cleats. I

might take a few turns on a customer’s

cleats with a line that leads back to my

deck, but the knots are all on my cleats.

Here is the logic behind this rule: when it

comes time to untie, you want to do it

fast, and your customer will be busy getting off his boat with his docklines. You don’t

want to be climbing between the two boats and over railings at that critical moment, so

plan for the ability to untie everything from your boat, even if I have to toss my lines on

his deck and then retrieve them when the job is done (while I do my paperwork). Also, I

do not want to give my customer any opportunity to untie something that I don’t want

untied, nor rely on him to untie a line quickly.

Rule #5: Use as few lines as possible. A great set up for most hip tows is to begin with a

forward spring line from your boat, and run that to his stern cleat. This is your

opportunity to set his transom way forward on your boat. Next, toss him a looped end of

a bow line (give him a loop so he can get it off quickly without untying any knots. Pull

your bow in and forward tight and cleat off on your bow bitt or cleat. Now go back and

take the rest of the stern line from his stern cleat back to your boat. A light tap in forward

will bring your stern in towards his, and if you’re quick, you will end up with a nice tight

hip tow that will only require you to untie one knotted cleat. When its time to untie, start

with your stern cleat and then unwrap his stern cleat. Now you’ve made enough slack

forward that a deckhand on the casualty can just take your loop off and drop it in the

water; or, you can untie from your bow while the mariner steps off his boat onto the

dock. (see diagram #3)

Rule #6: Get the lines tight. This insures that the

entire raft-up moves as one giant boat. If your lines

are sloppy, it becomes very hard to make small

adjustments while you are finessing the casualty into

a tight spot.

Being able to maneuver a large yacht while hipped

up to your smaller towboat will impress your

customers if you do it well, and with a little practice

and planning it is not hard to become proficient at it.

You might also like

- Dinghy Sailing Start to Finish: From Beginner to Advanced: The Perfect Guide to Improving Your Sailing SkillsFrom EverandDinghy Sailing Start to Finish: From Beginner to Advanced: The Perfect Guide to Improving Your Sailing SkillsNo ratings yet

- Anchoring Boat SafelyDocument2 pagesAnchoring Boat SafelyFajar IslamNo ratings yet

- Powerboating: The RIB & Sportsboat Handbook: Handling RIBs & SportsboatsFrom EverandPowerboating: The RIB & Sportsboat Handbook: Handling RIBs & SportsboatsNo ratings yet

- Seaworthy Offshore Sailboat: A Guide to Essential Features, Handling, and GearFrom EverandSeaworthy Offshore Sailboat: A Guide to Essential Features, Handling, and GearRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Anchoring and Ship HandlingDocument11 pagesAnchoring and Ship HandlingSunil Kumar100% (2)

- Boating Skills and Seamanship (EBOOK)From EverandBoating Skills and Seamanship (EBOOK)No ratings yet

- Multihull Seamanship: An A-Z of skills for catamarans & trimarans / cruising & racingFrom EverandMultihull Seamanship: An A-Z of skills for catamarans & trimarans / cruising & racingNo ratings yet

- Nautical Flags - A Collection of Historical Sailing Articles on the Use and Recognition of FlagsFrom EverandNautical Flags - A Collection of Historical Sailing Articles on the Use and Recognition of FlagsNo ratings yet

- The Island Hopping Digital Guide To The Windward Islands - Part III - BarbadosFrom EverandThe Island Hopping Digital Guide To The Windward Islands - Part III - BarbadosNo ratings yet

- The Blue Book of Sailing: The 22 Keys to Sailing MasteryFrom EverandThe Blue Book of Sailing: The 22 Keys to Sailing MasteryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- The International Marine Book of SailingFrom EverandThe International Marine Book of SailingRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- The Complete On-Board Celestial Navigator, 2007-2011 Edition: Everything But the SextantFrom EverandThe Complete On-Board Celestial Navigator, 2007-2011 Edition: Everything But the SextantNo ratings yet

- The Complete Rigger's Apprentice: Tools and Techniques for Modern and Traditional RiggingFrom EverandThe Complete Rigger's Apprentice: Tools and Techniques for Modern and Traditional RiggingNo ratings yet

- Sailboat Cowboys Flipping Sail Post-Sandy: The Art of Buying, Repairing and Selling Storm-Damaged SailboatsFrom EverandSailboat Cowboys Flipping Sail Post-Sandy: The Art of Buying, Repairing and Selling Storm-Damaged SailboatsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Emergency Navigation, 2nd Edition: Improvised and No-Instrument Methods for the Prudent MarinerFrom EverandEmergency Navigation, 2nd Edition: Improvised and No-Instrument Methods for the Prudent MarinerRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The Seaman's Friend Containing a treatise on practical seamanship, with plates, a dictinary of sea terms, customs and usages of the merchant serviceFrom EverandThe Seaman's Friend Containing a treatise on practical seamanship, with plates, a dictinary of sea terms, customs and usages of the merchant serviceNo ratings yet

- The Complete Anchoring Handbook: Stay Put on Any Bottom in Any WeatherFrom EverandThe Complete Anchoring Handbook: Stay Put on Any Bottom in Any WeatherRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- The Complete Trailer Sailor: How to Buy, Equip, and Handle Small Cruising SailboatsFrom EverandThe Complete Trailer Sailor: How to Buy, Equip, and Handle Small Cruising SailboatsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Modern Cruising Sailboat: A Complete Guide to its Design, Construction, and OutfittingFrom EverandThe Modern Cruising Sailboat: A Complete Guide to its Design, Construction, and OutfittingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- The Captains Guide to Hurricane Holes - Volume III - The Leeward Islands and the Windward IslandsFrom EverandThe Captains Guide to Hurricane Holes - Volume III - The Leeward Islands and the Windward IslandsNo ratings yet

- Hti1 Towage Guidelines v3Document16 pagesHti1 Towage Guidelines v3hgmNo ratings yet

- StabilityDocument3 pagesStabilityJeremy ParkerNo ratings yet

- GPS for Mariners, 2nd Edition: A Guide for the Recreational BoaterFrom EverandGPS for Mariners, 2nd Edition: A Guide for the Recreational BoaterRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Piloting, Seamanship and Small Boat Handling - Vol. VFrom EverandPiloting, Seamanship and Small Boat Handling - Vol. VRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Learn the Nautical Rules of the Road: The Essential Guide to the COLREGsFrom EverandLearn the Nautical Rules of the Road: The Essential Guide to the COLREGsNo ratings yet

- Practical Navigation for the Modern Boat Owner: Navigate Effectively by Getting the Most Out of Your Electronic DevicesFrom EverandPractical Navigation for the Modern Boat Owner: Navigate Effectively by Getting the Most Out of Your Electronic DevicesNo ratings yet

- Ship Manoeuvring-Closing The Safety LoopDocument13 pagesShip Manoeuvring-Closing The Safety LoopMichael ManuelNo ratings yet

- Small-Boat Sailing - An Explanation of the Management of Small Yachts, Half-Decked and Open Sailing-Boats of Various Rigs, Sailing on Sea and on River; Cruising, Etc.From EverandSmall-Boat Sailing - An Explanation of the Management of Small Yachts, Half-Decked and Open Sailing-Boats of Various Rigs, Sailing on Sea and on River; Cruising, Etc.No ratings yet

- Navigation Rules PDFDocument226 pagesNavigation Rules PDFobayonnnnnnnnnnnnnnnNo ratings yet

- Mastering Navigation at Sea: De-mystifying navigation for the cruising skipperFrom EverandMastering Navigation at Sea: De-mystifying navigation for the cruising skipperNo ratings yet

- Anchorages and Marinas of the Eastern Canaries: Sailing off the Coasts of Lanzarote, Fuerteventura and Gran CanariaFrom EverandAnchorages and Marinas of the Eastern Canaries: Sailing off the Coasts of Lanzarote, Fuerteventura and Gran CanariaNo ratings yet

- Navigation Rules and Regulations Handbook: International—InlandFrom EverandNavigation Rules and Regulations Handbook: International—InlandRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Once Around: Fulfilling a Life-long Dream to Sail Around the WorldFrom EverandOnce Around: Fulfilling a Life-long Dream to Sail Around the WorldNo ratings yet

- Fast Track to Cruising: How to Go from Novice to Cruise-Ready in Seven DaysFrom EverandFast Track to Cruising: How to Go from Novice to Cruise-Ready in Seven DaysNo ratings yet

- Practical Boat-Sailing: A Concise and Simple TreatiseFrom EverandPractical Boat-Sailing: A Concise and Simple TreatiseRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- West Country Cruising Companion: A yachtsman's pilot and cruising guide to ports and harbours from Portland Bill to Padstow, including the Isles of ScillyFrom EverandWest Country Cruising Companion: A yachtsman's pilot and cruising guide to ports and harbours from Portland Bill to Padstow, including the Isles of ScillyNo ratings yet

- The Skipper's Pocketbook: A Pocket Database For The Busy SkipperFrom EverandThe Skipper's Pocketbook: A Pocket Database For The Busy SkipperNo ratings yet

- Asymmetric Sailing: Get the Most From your Boat with Tips & Advice From Expert SailorsFrom EverandAsymmetric Sailing: Get the Most From your Boat with Tips & Advice From Expert SailorsNo ratings yet

- Aizimuth Tug BoatDocument3 pagesAizimuth Tug BoatTuan Dao QuangNo ratings yet

- Safety at Sea for Small-Scale Fishers in the CaribbeanFrom EverandSafety at Sea for Small-Scale Fishers in the CaribbeanNo ratings yet

- Gao Twic RPTDocument64 pagesGao Twic RPTDoug GouldNo ratings yet

- Emperors On Thin Ice Three Years of Breeding Failure at Halley BayDocument6 pagesEmperors On Thin Ice Three Years of Breeding Failure at Halley BayDoug GouldNo ratings yet

- 2010 Recreational Boating StatisticsDocument77 pages2010 Recreational Boating StatisticsDoug GouldNo ratings yet

- Towing Liability 2Document3 pagesTowing Liability 2Doug GouldNo ratings yet

- NTSB Factual Report On DUKW Boat CollisionDocument31 pagesNTSB Factual Report On DUKW Boat CollisionDoug GouldNo ratings yet

- Towing Liability 1Document3 pagesTowing Liability 1Doug GouldNo ratings yet

- NTSB Correction To USCG Preliminary InvestigationDocument2 pagesNTSB Correction To USCG Preliminary InvestigationDoug GouldNo ratings yet

- Shaft SealsDocument10 pagesShaft SealsDoug Gould100% (1)

- Uscg Mission Statement 2008Document76 pagesUscg Mission Statement 2008Doug GouldNo ratings yet

- NTSB Recommendation Re: Cell Phones On USCG BoatsDocument4 pagesNTSB Recommendation Re: Cell Phones On USCG BoatsDoug GouldNo ratings yet

- Identification Credential (Twic) Program in The Maritime SectorDocument63 pagesIdentification Credential (Twic) Program in The Maritime SectorDoug GouldNo ratings yet

- Calulating Submerged WeightDocument5 pagesCalulating Submerged WeightDoug Gould67% (6)

- GigidecisionDocument41 pagesGigidecisionDoug GouldNo ratings yet

- Radio ChecksDocument3 pagesRadio ChecksDoug GouldNo ratings yet

- TWIC Information Bulletin Feb 2009Document2 pagesTWIC Information Bulletin Feb 2009Doug GouldNo ratings yet

- Twin Vs SingleDocument7 pagesTwin Vs SingleDoug GouldNo ratings yet

- Conducting The Radio InterviewDocument5 pagesConducting The Radio InterviewDoug GouldNo ratings yet

- Uscg Boat Crew Seamanship Manual Chapter 15Document56 pagesUscg Boat Crew Seamanship Manual Chapter 15Doug Gould100% (1)

- Dealing With A DismatingDocument5 pagesDealing With A DismatingDoug GouldNo ratings yet

- Twic Small Entitie GuideDocument25 pagesTwic Small Entitie GuideDoug GouldNo ratings yet

- Uscg Document Change FormDocument2 pagesUscg Document Change FormDoug Gould100% (2)

- USCG Communications Watchstander Qualification GuideDocument133 pagesUSCG Communications Watchstander Qualification GuideONTOS66No ratings yet

- Section 4.1 Maritime SAR Assistance Policy (MSAP)Document10 pagesSection 4.1 Maritime SAR Assistance Policy (MSAP)Doug GouldNo ratings yet

- The International Convention On Salvage 1989: Chapter I - General ProvisionsDocument15 pagesThe International Convention On Salvage 1989: Chapter I - General ProvisionsNaeemNo ratings yet

- Indigenous or Traditional Fishing Crafts of IndiaDocument11 pagesIndigenous or Traditional Fishing Crafts of IndiaAbhi BlackNo ratings yet

- Ship To Ship (STS) Operations Plan:: ArrivalDocument3 pagesShip To Ship (STS) Operations Plan:: ArrivalBehendu PereraNo ratings yet

- 4th PartDocument37 pages4th PartPow JohnNo ratings yet

- Ves05 Errv Survey Guidelines Issue 5Document42 pagesVes05 Errv Survey Guidelines Issue 5Shah GulNo ratings yet

- Plan and Ensure Safe Loading, Stowage, Securing, Care During Voyage and Loading ofDocument122 pagesPlan and Ensure Safe Loading, Stowage, Securing, Care During Voyage and Loading ofBintangNo ratings yet

- Planter's Product v. CA DigestDocument3 pagesPlanter's Product v. CA DigestDGDelfinNo ratings yet

- Standard Bulk Cargoes-Hold Preparation and CleaningDocument32 pagesStandard Bulk Cargoes-Hold Preparation and CleaningSoyHan BeLen100% (3)

- Winners of The Congressman James Sener Award For Excellence in Marine Investigations (Cy2010)Document1 pageWinners of The Congressman James Sener Award For Excellence in Marine Investigations (Cy2010)cgreportNo ratings yet

- Lampedusa SmythDocument6 pagesLampedusa SmythDiego RattiNo ratings yet

- CV PantaleonDocument6 pagesCV PantaleonSande PantaleonNo ratings yet

- Ecdis FailureDocument2 pagesEcdis FailureAndrei CondruzNo ratings yet

- Shipborne Navigational Systems and EquipmentDocument10 pagesShipborne Navigational Systems and EquipmentAbdel Nasser Al-sheikh YousefNo ratings yet

- The Only Sci Fi ClichesDocument7 pagesThe Only Sci Fi Clichesdomingojs233710No ratings yet

- Riverine Patrol Vessels Battlefield Communications South Korea'S Armed ForcesDocument32 pagesRiverine Patrol Vessels Battlefield Communications South Korea'S Armed ForcesPEpuNo ratings yet

- RYA Competent Crew and Yacht Skipper PDFDocument221 pagesRYA Competent Crew and Yacht Skipper PDFAlchemistasNo ratings yet

- LIBERTY 100 01 07 09 Web PDFDocument2 pagesLIBERTY 100 01 07 09 Web PDFPatrizia CudinaNo ratings yet

- Different Types of Hatch CoversDocument1 pageDifferent Types of Hatch CoversKryle DusabanNo ratings yet

- Group 2 (Buatan Port)Document11 pagesGroup 2 (Buatan Port)imeldaelisabeth0% (1)

- EU Standards For BoatsDocument11 pagesEU Standards For BoatsRaniero FalzonNo ratings yet

- 10 Professional Mistakes Seafarers Should Never MakeDocument4 pages10 Professional Mistakes Seafarers Should Never Makeidhur61No ratings yet

- PropellerDocument4 pagesPropellerbolsjhevikNo ratings yet

- SQA Stability TheoryDocument10 pagesSQA Stability Theorysaurabh gulawaniNo ratings yet

- LR Ship's DimensionsDocument2 pagesLR Ship's DimensionsSignore DwiczNo ratings yet

- Ocean Engineering: Joshua Cutler, Musa Bashir, Yang Yang, Jin Wang, Sean LoughneyDocument2 pagesOcean Engineering: Joshua Cutler, Musa Bashir, Yang Yang, Jin Wang, Sean LoughneyAdrNo ratings yet

- Crest 2 Particular PDFDocument1 pageCrest 2 Particular PDFElhamy M. SobhyNo ratings yet

- Malaysian Notices To Mariners - Annual Edition 2018 ( ) Containing Annual Notice #1-27 - Temporary and Preliminary Notices PG #71 - 2018Document108 pagesMalaysian Notices To Mariners - Annual Edition 2018 ( ) Containing Annual Notice #1-27 - Temporary and Preliminary Notices PG #71 - 2018Lemuel GulliverNo ratings yet

- 0000the Shipping Law Review Ed 6cDocument632 pages0000the Shipping Law Review Ed 6cCléber MartinezNo ratings yet

- The Mystery of Bermuda TriangleDocument2 pagesThe Mystery of Bermuda TriangleKeren Mnhz ChispaNo ratings yet

- Complete Book of Anchoring and Mooring 1986 Hinz 0870333488Document321 pagesComplete Book of Anchoring and Mooring 1986 Hinz 0870333488Alchemistas100% (1)

- Cargo Record BookDocument8 pagesCargo Record BookKyrylo KirovNo ratings yet