Professional Documents

Culture Documents

HUD Comments - Warehouse Lending

Uploaded by

00aaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

HUD Comments - Warehouse Lending

Uploaded by

00aaCopyright:

Available Formats

COMMENTS On RESPA: Solicitation of Information on Changes in Warehouse Lending and Other Loan Funding Mechanisms [Docket No.

FR-5459-N-01] December 27, 2010

The National Association of Consumer Advocates 1 (NACA) and the National Consumer Law Center, 2 (NCLC) on behalf of its low income clients, submit these comments in response to the Department of Housing and Urban Developments Notice of Solicitation of Information on Changes in Warehouse Lending and Other Loan Funding Mechanisms (Docket No. FR-5459-N01).

I. Introduction: The Interests Protected by the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (RESPA)

Congress enacted RESPA in 1974 to effect certain changes in the settlement process for residential real estate. 12 U.S.C. 2601(b). The purpose of those changes was, among other things, to cause (1) . . . more effective advance disclosure to home buyers and sellers of

The National Association of Consumer Advocates (NACA) is a non-profit corporation whose members are private and public sector attorneys, legal services attorneys, law professors, and law students, whose primary focus involves the protection and representation of consumers. NACAs mission is to promote justice for all consumers. As part of its mission, NACA manages the Institute for Foreclosure Legal Assistance (IFLA), a program designed to fund and train organizations that help consumers protect their homes from foreclosure. 2 The National Consumer Law Center, Inc. (NCLC) is a non-profit Massachusetts Corporation, founded in 1969, specializing in low-income consumer issues, with an emphasis on consumer credit. On a daily basis, NCLC provides legal and technical consulting and assistance on consumer law issues to legal services, government, and private attorneys representing low-income consumers across the country. NCLC publishes a series of eighteen practice treatises and annual supplements on consumer credit laws, including Truth In Lending, (7th ed. 2010 (forthcoming)), Cost of Credit: Regulation, Preemption, and Industry Abuses (4th ed. 2009), and Foreclosures (3rd ed. 2010), as well as bimonthly newsletters on a range of topics related to consumer credit issues and low-income consumers. NCLC attorneys have written and advocated extensively on all aspects of consumer law affecting low-income people, conducted training for thousands of legal services and private attorneys on the law and litigation strategies to address predatory lending and other consumer law problems, and provided extensive oral and written testimony to numerous Congressional committees on these topics. NCLC's attorneys have been closely involved with the enactment of the all federal laws affecting consumer credit since the 1970s, and regularly provide extensive comments to the federal agencies on the regulations under these laws.

settlement costs; [and] (2) . . . the elimination of kickbacks or referral fees that tend to increase unnecessarily the costs of certain settlement services. Id. The statute was enacted against the background of congressional findings that significant reforms in the real estate settlement process are needed to insure that consumers throughout the Nation are provided with greater and more timely information on the nature and costs of the settlement process and are protected from unnecessarily high settlement charges caused by certain abusive practices that have developed in some areas of the country. 12 U.S.C. 2601(a). RESPA consequently sweeps broadly. RESPA covers consumer transactions respecting any federally related mortgage loan, id. 2601(1), 2607, a term that encompasses virtually every consumer mortgage transaction; and the referral of any settlement service, which consists of the origination of a federally related mortgage loan, including, but not limited to, . . . the underwriting and funding of loans . . .. Id. There have been changes in the real estate settlement services industry since 1974, but nothing suggests that Congresss original purpose was misplaced or that the scope of the statute should be diminished. Indeed, many of the changes since 1974 by the settlement services industry have been aimed at evading the scope of the statute. On the rare occasion that Congress has revisited RESPA, it has made clear that the same concerns as in 1974 remain valid today. In 1983, for example, Congress addressed Controlled Business Arrangements, recognizing that these arrangements could harm consumers in several ways: [T]he advice of the person making the referral may lose its impartiality and may not be based on his professional evaluation of the quality of service provided if the referrer or his associates have a financial interest in the company being recommended. In

addition, since the real estate industry is structured so that settlement service providers do not compete for a consumers business directly, but almost exclusively rely on referrals from real estate brokers, lenders or their associates for their business, the growth of controlled business arrangements effectively reduce the kind of healthy competition generated by independent settlement service providers. [H.R. Rep. No. 97-532, 97th Cong., 2nd Sess. at p. 52 (1982).] As a result, today all such arrangements are subject to explicit restrictions, see 12 U.S.C. 2607(c)(4). Other changes since 1974 such as the role of mortgage brokers in the real estate lending processhave, if anything, underlined the need for a robust, expansive RESPA statute and enforcement process. Narrowing the statute would be directly contrary to Congresss stated (and since repeated) intent in enacting the statute.

II.

Background on Warehouse Lending and Table-Funding

Warehouse lines of credit, as HUD is fully aware, are a legal and unexceptional way for

mortgage lenders who lack access to the deposit base of funds to obtain liquidity so that they can engage in mortgage loan transactions. In a standard, arms-length warehouse lending transaction, an unaffiliated warehouse lender and its mortgage banker borrower enter into commercially reasonable, market-based transactions that govern the terms, interest rate, underwriting standards, repayment and replenishment terms, and other similar matters. For example, the interest rate on warehouse lines is often set at the one-month LIBOR rate plus a spread. Other transaction terms will vary, but in a genuinely arms-length lending relationship, they will all be market-based. Such independent lending relationships can and we stress can -- result in a bona fide secondary market transaction within the meaning of the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (RESPA), see 24 C.F.R. 3500.5(b)(7).

By contrast, transactions between related or affiliated parties are often denominated warehouse lines of credit when they are actually table-funded transactions. Table-funded transactions are ones in which the funding and assignment of the loan occur contemporaneously. HUD has long recognized that a table-funded transaction is not a secondary market transaction. 24 C.F.R. 3500.2. Nothing that we have seen suggests that this restriction should be loosened or changed. Yet changes to the warehouse lending definition could do this by ignoring the role of affiliated entities. When the so-called warehouse lending occurs between one entity and another controlled or related entity (a captive mortgage lender), which makes mortgage loans, the terms of the loan may be unusual. In court records recently unsealed in a RESPA case filed in federal court in Maryland, for example, the mortgage lender was owned by a bank, which also acted as the mortgage lenders warehouse lender. The mortgage lenders records revealed that it paid no interest whatsoever to its owner/warehouse lender despite the extension of credit for hundreds of millions of dollars. See Minter v. Wells Fargo Bank. N.A., No. 07-cv-03442-WMN (D. Md.), Dkt. Entry #186, pp. 21-22. In such a situation, there is plainly no shelter from RESPAs restrictions, nor should there be. 3 Frequently, captive mortgage lenders routinely sell or assign most of the loans they originate back to the warehouse lender, in another marker of transfers that are not arms-length or bona fide as required by 24 C.F.R. 3500.5(b)(7). We have seen cases in which a captive mortgage lender assigns or transfers 90% or more of its loans back to a related-party mortgage

The Notice asks for comments on how warehouse lending [has] evolved since HUD issued is 1994 regulations. Practices in such related-party transactions may have evolved, but not in a positive way. Schemes established to evade RESPAs anti-kickback rules, or to skirt the requirements of the Affiliated Business Arrangement rules, should be subject to RESPA scrutiny, whether they are termed warehouse lines of credit or not.

lender, which also happens to be an owner or affiliate of the captive mortgage lender. See, e.g., Petry v. Prosperity Mortgage Company, 07-CV-03442 (D. Md.), Dkt. Entry #124, pp. 22-23, 31, 32. In such related party cases, the fact that the mortgage lender sells a high proportion of its loans back to its warehouse lender indicates that the transaction is anything but arms length. In light of Congresss clearly expressed intent about the scope of RESPA, discussed above, narrowing via regulation or policy statement would be directly contrary to the purpose of the statute. Even if new guidance by HUD would be appropriate in certain circumstances, nothing would justify a relaxation of the rules in the context of related party transactions, such as warehouse lines of credit extended by one owner or affiliate to another.

III. Current Rules and Interpretations Regarding Secondary Market Transactions, Warehouse Lending and Table-Funding Should Not Be Altered

A. Given Congresss Intent and the Potential for Abuse, RESPAs Protections Should Not Be Narrowed The Warehouse Lending Notice suggests that HUD is considering revising or even narrowing the protections afforded by RESPA to consumers in certain types of loans that involve warehouse lending. Given the broad sweep of the statutes language and Congresss plainly expressed intent about the need for stringent controls on anticompetitive conduct, there is no basis for such action. The history of the settlement service industry since RESPAs enactment is one of increasing sophistication and efforts to avoid RESPAs requirements through the creation of Affiliated Business Arrangements and other means. But even if there is some justification for action, related party transactions like the ones described above should never be exempted from RESPAs prohibitions as secondary market transactions. When related parties structure a warehouse line of credit or assign loans to each other, the opportunities for manipulation are apparent. Simply put, such a loan transaction is

never a bona fide transfer of a loan obligation to the secondary market. 24 C.F.R. 3500.5(b)(7). It is all too easy to structure such arrangements in a way that might comply with the letter of a regulation or policy statement. HUD should not encourage the real estate industry to invent new schemes that will shrink the scope of RESPA, and such an action would encourage precisely this conduct. B. The Federal Courts have Relied on HUDs Existing Interpretations to Build a Body of Law That Properly Interprets RESPAs Protections in Related Party Cases HUD should be extremely cautious about redefining the scope of RESPAs protections because the federal courts of appeal have relied on HUDs existing interpretation to erect a body of law that provides an appropriate level of protection for consumers. See Moreno v. Summit Mtg. Corp., 364 F.3d 574 (5th Cir. 2004); Chandler v. Norwest Bank Minnesota, N.A., 137 F.3d 1053 (8th Cir. 1998). Under these decisions, a mortgage purchased by the same warehouse lender who supplied the funds for the mortgage loan falls outside the RESPA secondary market exemption. Using such a captive line of credit makes a lender subject to RESPA. In Chandler, for example, in finding that the loan was not table-funded and thus not subject to RESPAs protections against kickbacks, the court underlined the importance of having a warehouse lender separate from the ultimate purchaser, taking pains to repeat, The Chandlers have neither alleged nor shown any affiliation between CoreStates and Norwest. Id. at 1056 n.5. Similarly, in Moreno v. Summit Mtg., the Fifth Circuit followed Chandler in analyzing a loan sold by the defendant lender, Summit Mortgage. For the loans it originated, Summit borrowed the money to fund them from its warehouse lender, Bank United. 364 F.3d at 575. When Summit sold the loan to a genuine third party, First Nationwide, the Fifth Circuit found that this was a secondary market transaction. As in Chandler, Summit borrowed the money to fund the Morenos' mortgage loan through its established line of credit with Bank United, not First

Nationwide. Id. at 577 (emphasis added). Under this jurisprudence, bona fide purchasers and legitimate warehouse lenders are already protected, while sham transactions are subject to greater scrutiny. These decisions, of course, illustrate the way that bona fide, arms-length lending relationships work in the market, and are thus directly responsive to HUDs request for such information. But just as important, they demonstrate that the current approach, under existing HUD guidance, is working well and does not require change or correction. Moreover, these decisions suggest that the courts have relied to a significant extent on HUDs current interpretation of RESPA and its exemptions. Any change to that interpretation would carry significant risks.

IV.

The Risks Involved in Loosening Controls over Table-Funded Transactions

The Warehouse Lending Notice suggests that HUD is considering changing or diluting

RESPA protections for consumers who finance the purchase of a home through table funding involving warehouse lenders. As explained above, current HUD regulations make clear that table-funded loans where a lender closes a loan in its own name using funds advanced by another party and then contemporaneously assigns that loan to that funding party (see 24 CFR 3500.2(15)) are not secondary market transactions. As a result, table-funded mortgage transactions which typically involve origination through a mortgage broker or an affiliated company are covered by the full panoply of RESPA protections (e.g., prohibition on kickbacks, required disclosures, regulation of Affiliated Business Arrangements or ABAs, etc.). See 24 CFR 3500.5(b)(7). The Warehouse Lending Notice suggests consideration of a

process which blur, if not totally eliminate, this line between bona fide secondary market transactions and table-funded mortgages. Such an action would lead to terrible results for consumers. It would diminish RESPAs coverage over a large segment of mortgage lending. If table-funding involving warehouse lenders is removed from the scope of RESPA protection, we have no doubt that the nontransparent business model this would allow would significantly increase the cost of home loans to American consumers. In fact, we have seen this already attempted where table-funding is already used by large institutional lenders who set up sham ABA lenders with real estate brokers, mortgage brokers, and others to facilitate illegal kickbacks for referrals of business. These large lenders advance mortgage funds to sham ABA lenders, who, contemporaneous with the closing, assign the loans to the real lender i.e., the true source of funds in the transaction. In table-funded transactions, the true identity of the actual lender is concealed from the borrower. In such transactions, the borrower is often saddled with thousands of dollars in unnecessary and illegal underwriting, administrative, application, processing and similar junk fees. The terms of the table-funding transaction may require the imposition of those fees directly or may encourage them as a way of paying kickbacks along the chain. As explained above, at least two federal circuit courts have already held that such tablefunding practices are subject to RESPA, 4 and several state courts, following HUDs current regulations and policies, have found that table-funding facilitated predatory practices such as loan-flipping. Moreover, a number of lawsuits are currently pending around the country challenging various table-funding abuses. Often, as explained above, the advance of funds by

Moreno v. Summit Mtg. Corp., supra; Chandler v. Norwest Bank Minnesota N.A., supra.

the real lender in a table-funded mortgage is done through what the lender will call a warehouse line of credit, but the effect is the same a concealed lender charging and receiving inflated settlement fees. The HUD guidance that the Warehouse Lending Notice anticipates being issued will enable these abusive practices. Such a move by HUD now, when Americans are still reeling from a recession fueled by a spate of disastrous predatory banking practices including many caused by table-funded lending in the subprime market is a recipe for disaster and is the last thing American consumers need today. Finally, and frankly, we remain concerned about HUDs decision to issue this Warehouse Lending Notice. First, with the pending start-up of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), we believe HUD should issue no new rules or opinions on RESPA, but leave rulemaking under RESPA to the CFPB, which is charged with both rulemaking under RESPA and research into many different matters relating to consumer lending. Second, we strongly believe that there are far more pressing issues in the mortgage lending and servicing marketplace for all regulators, including both the CFPB and HUD, to focus on. Loosening the standards for warehouse lending or table-funded transactions is a response to a problem that doesnt need to be fixed. Bona fide secondary market transactions are currently exempt from RESPA and require no additional HUD interpretations or guidance; and genuine warehouse lenders (large financial institutions which extend credit to unrelated, unaffiliated mortgage lenders) do not run afoul of RESPA unless they table-fund. Under current HUD regulation and policy, RESPA is working as intended and covers residential home mortgage transactions, regardless of the funding method employed.

There is no valid reason to carve out an exemption from RESPA for one segment of mortgage transactions, i.e., where the mortgage is table-funded through fictional warehouse lending. Indeed, if HUD were to exempt table-funded warehouse loans to affiliated entities from RESPA, we are certain that the mortgage industry as a whole would re-tool itself to exploit such a large and gaping RESPA loophole. Even if there were a problem that needed addressing, the contemplated cure would end up killing the patient.

V.

The Mortgage Lending Industry Seeks to Preempt Efforts to Build a Fair and Accountable Mortgage Lending System

As of the submission of these comments, twenty-two industry related businesses and

trade groups have submitted comments to HUD regarding the "need" for changes to HUD's regulations regarding warehouse lending. HUD's November 24 Notice, however, requested comments from the industry and others on "changes in warehouse lending and other finance mechanisms" since 1992. The comments submitted from the industry fail to address any such changes or evolutions; rather, the comments simply urge changes to regulations that will exempt "table funding" from HUD and RESPA's regulation. The comments urge changes to HUD's treatment of "table funding" that will have serious repercussions for consumers: 1. Changing the current regulations would undermine attempts to hold mortgage lenders responsible for the quality of loans they fund. Table-funded transactions allow poorly capitalized entitiesoften mortgage brokers masquerading as legitimate lendersto originate loans without retaining any liability for those loans. If a table funded loan, originated by a mortgage broker, is considered a secondary market transaction, and thus outside the regulation of RESPA, then institutional lenders will have less incentive to police the underwriting and other origination activities of the assignor. Large institutional lenders could establish sham lending affiliates with real estate brokers and other referral sources, merely by running the mortgage funds through a

2.

warehouse line of credit. At the moment such transactions fall within RESPA. If the changes suggested by the industry are adopted, then sham lending will become institutionalized, with large opportunities for unregulated and often undiscoverable kickbacks. Not only would consumers be harmed by this kickback arrangement, small businesses (including more moderate size lenders that do not have the resources to establish such affiliates) will suffer a competitive disadvantage.

In the end, any changes to HUD's current regulations would be short sighted. Expanding the reach of the warehouse lending exceptions could have a serious impact on consumers and the economic recovery. As the comments and submissions to date suggest, the industry is not seeking merely to modify current HUD regulations; rather the industry is urging HUD to stop regulating many of the very types of predatory practices that gave rise to the mortgage crisis of 2008. For these reasons, we suggest that no further action or guidance by HUD is required, particularly not in the case of affiliated or related-party transactions involving so-called warehouse lines of credit. Respectfully Submitted,

Ira Rheingold National Association of Consumer Advocates 1730 Rhode Island Ave. NW, #710 Washington DC 20036 Diane Thompson National Consumer Law Center 1001 Connecticut Avenue N.W. S. 510 Washington DC 20036

You might also like

- The Appropriations Law Answer Book: A Q&A Guide to Fiscal LawFrom EverandThe Appropriations Law Answer Book: A Q&A Guide to Fiscal LawNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document24 pagesChapter 4John DoeNo ratings yet

- Court - Affirmation To Motion To Compel PDFDocument4 pagesCourt - Affirmation To Motion To Compel PDFosvaldo valdesNo ratings yet

- Chery v. Conduent EducationDocument15 pagesChery v. Conduent EducationMooreKuehnNo ratings yet

- The State Owned Enterprise As A Vehicle For StabilityDocument72 pagesThe State Owned Enterprise As A Vehicle For StabilityYemmanAllibNo ratings yet

- Brevard CountyDocument3 pagesBrevard CountyMichel WatsonNo ratings yet

- IZE V Experian - DOC 35 - Order On MTDDocument8 pagesIZE V Experian - DOC 35 - Order On MTDKenneth G. EadeNo ratings yet

- Complaint Citigroup in RemDocument7 pagesComplaint Citigroup in RemmschwimmerNo ratings yet

- Judicial Affidavit Rule: Object 1Document4 pagesJudicial Affidavit Rule: Object 1bbysheNo ratings yet

- Subpoena LamarDocument8 pagesSubpoena LamarRuss LatinoNo ratings yet

- 2202-3978375 - 2022 FTL - IRS - and - Form - 990 - Updates - FINALDocument66 pages2202-3978375 - 2022 FTL - IRS - and - Form - 990 - Updates - FINALJamesMinionNo ratings yet

- Via Email & U.S. Mail: Steven - Mnuchin@treasury - GovDocument5 pagesVia Email & U.S. Mail: Steven - Mnuchin@treasury - GovJason PuhrNo ratings yet

- GreatGigz V ZipRecruiter - Order Granting MTDDocument12 pagesGreatGigz V ZipRecruiter - Order Granting MTDSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- 6 Franklin County Filing - OneOhio Open MeetingsDocument58 pages6 Franklin County Filing - OneOhio Open MeetingsTitus WuNo ratings yet

- Yes There Is A Citizen of Another StateDocument12 pagesYes There Is A Citizen of Another StateDan Goodman0% (1)

- V V V V:) V) V5V$V VV V VV9V8) VVDocument2 pagesV V V V:) V) V5V$V VV V VV9V8) VVBhavneesh ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Equifax Ethics ReportDocument9 pagesEquifax Ethics ReportAaminah KhanNo ratings yet

- Brads Response To Void Orders As of 1 March 2023Document18 pagesBrads Response To Void Orders As of 1 March 2023Sue BozgozNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Second CircuitDocument3 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Second CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Washington Mutual (WMI) - Motion of Shareholder William Duke To Allow Certain Documents and InformationDocument148 pagesWashington Mutual (WMI) - Motion of Shareholder William Duke To Allow Certain Documents and InformationmeischerNo ratings yet

- Groundless Litigation and The Malicious Prosecution Debate A Historical AnalysisDocument21 pagesGroundless Litigation and The Malicious Prosecution Debate A Historical AnalysisKroos DominicNo ratings yet

- A Two Phased Decision MakingDocument12 pagesA Two Phased Decision MakingK60 Nguyễn Ngọc HùngNo ratings yet

- Maxims of EquityDocument15 pagesMaxims of Equitygurnoor mutrejaNo ratings yet

- Rhode Island Public Pension Reform-Wall Street's License To StealDocument106 pagesRhode Island Public Pension Reform-Wall Street's License To StealGoLocal100% (2)

- Fiancial Market InfrastructureDocument16 pagesFiancial Market InfrastructureBoubacar Zakari WARGONo ratings yet

- BNK604 Handouts 1 45Document175 pagesBNK604 Handouts 1 45Hufzi KhanNo ratings yet

- Master Circular On Rbi Circular - Circular On Forex Risk ManagementDocument95 pagesMaster Circular On Rbi Circular - Circular On Forex Risk ManagementBathina Srinivasa RaoNo ratings yet

- Marshall Brown, Legal Effects of RecognitionDocument25 pagesMarshall Brown, Legal Effects of RecognitionKajjea KajeaNo ratings yet

- 2.c. Torts and DamagesDocument30 pages2.c. Torts and DamagesArann PilandeNo ratings yet

- Hero LawsuitDocument38 pagesHero LawsuitAnonymous 6f8RIS6No ratings yet

- Bill 30 Parking BillDocument34 pagesBill 30 Parking BillLVNewsdotcomNo ratings yet

- Rough Draft Qualified ImmunityDocument7 pagesRough Draft Qualified Immunityapi-609250441No ratings yet

- Pena V VDH - Oral Arguements - Sketch Order & Opinion LetterDocument15 pagesPena V VDH - Oral Arguements - Sketch Order & Opinion LetterAnthony DocKek PenaNo ratings yet

- HARIHAR V WELLS FARGO, Et Al (Docket No. 1981-cv-00050) - Court Order To E-File and Plaintiff's Extended Offer To Resume Settlement DiscussionDocument44 pagesHARIHAR V WELLS FARGO, Et Al (Docket No. 1981-cv-00050) - Court Order To E-File and Plaintiff's Extended Offer To Resume Settlement DiscussionMohan HariharNo ratings yet

- Mercy FilingDocument17 pagesMercy FilingAnonymous 6f8RIS6No ratings yet

- Institution of Legal Proceedings Against Certain Organs of State Act 40 of 2002Document8 pagesInstitution of Legal Proceedings Against Certain Organs of State Act 40 of 2002Vallaraman KathuravalooNo ratings yet

- LawDocument1 pageLawManojNo ratings yet

- In Re: Gloria Alcordo Estillore, 9th Cir. BAP (2017)Document19 pagesIn Re: Gloria Alcordo Estillore, 9th Cir. BAP (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Piercing The Corporate Veil. CasesDocument104 pagesPiercing The Corporate Veil. CasesVal Justin DeatrasNo ratings yet

- NZX Ecoya Media ReleaseDocument4 pagesNZX Ecoya Media ReleaseAlphatrader.co.nzNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Sub Agent and Substitute Agent - Aviral PathakDocument10 pagesDifference Between Sub Agent and Substitute Agent - Aviral PathakAviral PathakNo ratings yet

- Eng ApeelDocument9 pagesEng ApeelSouth AustralianNo ratings yet

- United States Bankruptcy Court Eastern District of MichiganDocument28 pagesUnited States Bankruptcy Court Eastern District of Michiganjohnathen savannah100% (1)

- CRS - Former Presidents' Pensions, Office Allowances, and Other Federal BenefitsDocument27 pagesCRS - Former Presidents' Pensions, Office Allowances, and Other Federal BenefitsZenger NewsNo ratings yet

- The Court of Appeal: Joseph Nduvi Mbuvi V Republic (2019) eKLRDocument2 pagesThe Court of Appeal: Joseph Nduvi Mbuvi V Republic (2019) eKLRLaelia KagikaNo ratings yet

- Southwestern Law TAA Presentation 2021Document19 pagesSouthwestern Law TAA Presentation 2021rick siegelNo ratings yet

- Motion For Stay and TRO in NMDocument25 pagesMotion For Stay and TRO in NMTom FranklinNo ratings yet

- Figueroa V MERS Doc 184 Order Dismissing Case With PrejudiceDocument35 pagesFigueroa V MERS Doc 184 Order Dismissing Case With Prejudicelarry-612445No ratings yet

- Roll No 140 Vicarious LiablityDocument12 pagesRoll No 140 Vicarious Liablitydnyanesh177No ratings yet

- Ruling Between AgCountry Farm Credit Services and Tri-County Livestock ExchangeDocument13 pagesRuling Between AgCountry Farm Credit Services and Tri-County Livestock ExchangeMichael JohnsonNo ratings yet

- The Community Development Investment Tax Credit ActDocument11 pagesThe Community Development Investment Tax Credit ActRuss LatinoNo ratings yet

- Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, and Order Re: Rule 11Document10 pagesFindings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, and Order Re: Rule 11griz8791No ratings yet

- Metro Regional Info V Am. Home Realty 1stDocument32 pagesMetro Regional Info V Am. Home Realty 1stpropertyintangibleNo ratings yet

- Decision Order and Declaration To Restore The LawDocument59 pagesDecision Order and Declaration To Restore The LawBarbara RoweNo ratings yet

- International Financial MGMT - 2Document49 pagesInternational Financial MGMT - 2Josh ChNo ratings yet

- Figs v. My Open Heart - ComplaintDocument30 pagesFigs v. My Open Heart - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Judges, Fairness, and Litigants in PersonDocument45 pagesJudges, Fairness, and Litigants in PersonKevin TalbertNo ratings yet

- Petition For Extraordinary ReliefDocument3 pagesPetition For Extraordinary ReliefAdam Forgie100% (1)

- Chris Summers RedactedDocument38 pagesChris Summers Redactedthe kingfishNo ratings yet

- Soy The Poison SeedDocument2 pagesSoy The Poison Seedgraduated12No ratings yet

- Outline of Lender Liability IssuesDocument22 pagesOutline of Lender Liability Issues00aaNo ratings yet

- Michele Sjolander, An Alleged Executive Vice President DepositionDocument25 pagesMichele Sjolander, An Alleged Executive Vice President DepositionRazmik BoghossianNo ratings yet

- Testimony of Julia Gordon, Center For Responsible LendingDocument24 pagesTestimony of Julia Gordon, Center For Responsible Lending00aaNo ratings yet

- Testimony of Richard BowenDocument21 pagesTestimony of Richard Bowen00aaNo ratings yet

- SecuritizationDocument89 pagesSecuritizationperezdeleonNo ratings yet

- Georgetown Professor Adam Levetin On Securitization Senate Testimony 11-06-10Document27 pagesGeorgetown Professor Adam Levetin On Securitization Senate Testimony 11-06-10chunga85100% (1)

- Nguyen Case - Handwriting Expert OpinionDocument31 pagesNguyen Case - Handwriting Expert Opinion00aaNo ratings yet

- WF Testimony of Allen Jones Tee On Housing 11-18-2010Document10 pagesWF Testimony of Allen Jones Tee On Housing 11-18-2010John ReedNo ratings yet

- Lender Liability Law Report - HUDDocument8 pagesLender Liability Law Report - HUD00aaNo ratings yet

- Banking Financial Services Article - Aiding Abetting Fraudulent or Predatory Lending2 (July 2010)Document10 pagesBanking Financial Services Article - Aiding Abetting Fraudulent or Predatory Lending2 (July 2010)00aaNo ratings yet

- Report On Fraudulent & Forged Assignments of Mortgages & Deeds in U.S. ForeclosuresDocument88 pagesReport On Fraudulent & Forged Assignments of Mortgages & Deeds in U.S. ForeclosuresForeclosure Fraud94% (36)

- (Goldman Sachs) A Mortgage Product PrimerDocument141 pages(Goldman Sachs) A Mortgage Product Primer00aaNo ratings yet

- Fraudulent ConveyanceDocument1 pageFraudulent Conveyance00aaNo ratings yet

- Nguyen Quiet TitleDocument4 pagesNguyen Quiet Title00aaNo ratings yet

- (JP Morgan) All You Ever Wanted To Know About Corporate Hybrids But Were Afraid To AskDocument20 pages(JP Morgan) All You Ever Wanted To Know About Corporate Hybrids But Were Afraid To Ask00aa100% (2)

- 101116-Kemp V CountryWide NJDocument22 pages101116-Kemp V CountryWide NJMike_Dillon100% (4)

- Nguyen - Complaint - June 25 2009Document86 pagesNguyen - Complaint - June 25 200900aaNo ratings yet

- Testimony - BofA - Rebecca MarinoeDocument7 pagesTestimony - BofA - Rebecca Marinoe00aaNo ratings yet

- Testimony of OCC - John WalshDocument19 pagesTestimony of OCC - John Walsh00aaNo ratings yet

- 101116-Kemp V CountryWide NJDocument22 pages101116-Kemp V CountryWide NJMike_Dillon100% (4)

- (ISDA, Altman) Analyzing and Explaining Default Recovery RatesDocument97 pages(ISDA, Altman) Analyzing and Explaining Default Recovery Rates00aaNo ratings yet

- (Goldman Sachs) Introduction To Mortgage-Backed Securities and Other Securitized AssetsDocument20 pages(Goldman Sachs) Introduction To Mortgage-Backed Securities and Other Securitized Assets00aa100% (4)

- CDO-Handbook - JP Morgan 2002Document52 pagesCDO-Handbook - JP Morgan 2002nagobadsNo ratings yet

- Fidelity's (LPS) Secret Deals With Mortgage Companies and Law FirmsDocument36 pagesFidelity's (LPS) Secret Deals With Mortgage Companies and Law FirmsForeclosure Fraud100% (1)

- Fitch Ratings) Asset-Backed Commercial Paper ExplainedDocument16 pagesFitch Ratings) Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Explained00aaNo ratings yet

- NY Fed Negative Repo RatesDocument7 pagesNY Fed Negative Repo RatesZerohedgeNo ratings yet

- (Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago) Structured NotesDocument24 pages(Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago) Structured Notes00aaNo ratings yet

- (Deutsche Bank) Depositary Receipts HandbookDocument22 pages(Deutsche Bank) Depositary Receipts Handbook00aaNo ratings yet

- (Egar Technology) Weather DerivativesDocument4 pages(Egar Technology) Weather Derivatives00aaNo ratings yet

- Deepak Bank StatementDocument25 pagesDeepak Bank StatementHemant BhattNo ratings yet

- Visa Digital Currency OverviewDocument12 pagesVisa Digital Currency OverviewViviane BocalonNo ratings yet

- Important Committees Related To Banking and FinanceDocument8 pagesImportant Committees Related To Banking and FinanceViraj Choubey50% (2)

- Md Ismail: Date خيراتلاDescription 6تانايبلاAmount Amount Balance ديصرلاDocument2 pagesMd Ismail: Date خيراتلاDescription 6تانايبلاAmount Amount Balance ديصرلاAiman Raja0% (2)

- 2nd PT-Business Finance-Final Exam-2022-2023Document3 pages2nd PT-Business Finance-Final Exam-2022-2023Diane GuilaranNo ratings yet

- FinanceDocument4 pagesFinanceFrancisco QuintanillaNo ratings yet

- Bond Equivalent Yield Financial MarketsDocument5 pagesBond Equivalent Yield Financial MarketsLianne PadillaNo ratings yet

- Financial Markets Institutions and Money 3Rd Edition Kidwell Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument27 pagesFinancial Markets Institutions and Money 3Rd Edition Kidwell Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFalicebellamyq3yj100% (12)

- What Is A Cheque Truncation System?Document7 pagesWhat Is A Cheque Truncation System?PrramakrishnanRamaKrishnanNo ratings yet

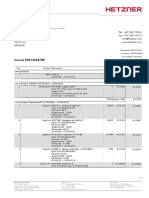

- Hetzner 2021-06-22 R0013604788Document2 pagesHetzner 2021-06-22 R0013604788Vitaliy PodobaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 25: Step by Step Murabaha Financing: Bank ClientDocument3 pagesChapter 25: Step by Step Murabaha Financing: Bank ClientAlton JurahNo ratings yet

- Cash & Cash EquivalentDocument3 pagesCash & Cash Equivalentdeborah grace sagarioNo ratings yet

- British CouncilDocument1 pageBritish CouncilHarpreetSinghNo ratings yet

- Deficiency of Services in BanksDocument10 pagesDeficiency of Services in Banksshaqueeb nallamanduNo ratings yet

- ACI Dealing Certificate: SyllabusDocument12 pagesACI Dealing Certificate: SyllabusKhaldon AbusairNo ratings yet

- K2A Trading Journal FXDocument11 pagesK2A Trading Journal FXmrsk1801No ratings yet

- Cash ManagementDocument20 pagesCash ManagementRahul DewakarNo ratings yet

- Challanform 1570936550Document1 pageChallanform 1570936550malik awanNo ratings yet

- Win22 Pill1A2 RBI Monetary Policy MrunalDocument13 pagesWin22 Pill1A2 RBI Monetary Policy MrunalVinay H PNo ratings yet

- BRS Tax and InstDocument25 pagesBRS Tax and InstNivedhitha BalajiNo ratings yet

- Micro Finance Banks in IndiaDocument9 pagesMicro Finance Banks in IndiaRajat SinghNo ratings yet

- Accounting Cycle: Exercise 6.1Document11 pagesAccounting Cycle: Exercise 6.1Joanna GarciaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Banking Sector Npa'S On Indian EconomyDocument9 pagesImpact of Banking Sector Npa'S On Indian EconomyKaran Veer SinghNo ratings yet

- Handout Mathematics of Investment PDFDocument36 pagesHandout Mathematics of Investment PDFJhon Carlo Delmonte100% (6)

- Universal BankingDocument13 pagesUniversal BankingmangundesanjuNo ratings yet

- Project in Fin Acc Chester Gutierrez Project in Fin Acc Chester GutierrezDocument17 pagesProject in Fin Acc Chester Gutierrez Project in Fin Acc Chester GutierrezJoseph Asis50% (2)

- Hamim Al Mukit - General Banking of Pubali Bank LTDDocument42 pagesHamim Al Mukit - General Banking of Pubali Bank LTDHamim Al MukitNo ratings yet

- Economic FileDocument135 pagesEconomic Filemonikarohilla33No ratings yet

- Account Activity Generated Through HBL MobileDocument1 pageAccount Activity Generated Through HBL MobileMuhammad WaseemNo ratings yet

- SBI Life Cerificate PDFDocument1 pageSBI Life Cerificate PDFsachin sawantNo ratings yet