Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Engleza

Uploaded by

Oana PopaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

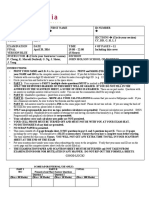

Engleza

Uploaded by

Oana PopaCopyright:

Available Formats

The peddlers were selling not more expensive than the market.

Sometimes even cheaper, due to early morning provisioning and they would not rise the commodities price during the day, as sometimes happened in the market. But even when they were selling more expensive it would still worth buying from them. It was better quality merchandise and fresh. In addition, it was sold by known people who had no reason to cheat, because they would lose customers and couldnt earn new ones. We are in a time when consumer articles are found in abundance (late nineteenth century and early twentieth century). The prices are not high compared with existing purchasing power. According to Constantin Kiritescu calculations, the lowest clerk - copyist, messenger, the signalman - had around 60 lei per month (in 1890, even 120). A head office exceeded 260 -270 lei, a teacher - 220 lei, a captain - 360-400 lei, a regional doctor - 480, a day laborer - 2 lei per day, a qualified worker - 3-4 lei per day. It is found that prices of the main food products would not increase but decrease. Even more interesting is this finding as in the meantime, the salaries grow, although not significantly. Prices needed to be seen also through the operation of bargaining, which began to play an increasingly important role in trade. The best traders were appreciated by bargaining skills. At that time, it was not referred to advertisement as the soul of commerce, but honor. What was good was good. And was even better if you knew how brag about it. Carts had numbers and weighing machines. Permit was not necessary for those who sold in fairs as they lasted, for those who traded in localities certain specified goods or selling newspapers, books, brochures. This includes the fiddlers who could exercise their profession anywhere and at any time. Permit was needed though, for monkeys and bears players, organ grinders, those who claimed to predict the future, clowns. Strolling merchants, as they were called, those sellers of everything or "Marchitani", they were everywhere. Most vendors were known by buyers. Those who were selling freshly milk, cheese, butter, Rumanian pressed cheese, cream, yoghurt, came to Bucharest usually from neighboring villages, each family had its own milkman, or Oltenian guy if the merchandise was different. Most of these Oltenians were young up to thirty years old, walking in a hurry, almost running, with their baskets jumping, and shouting their goods. They had their streets where their customers use to walk; they were entering the yard, put down the baskets and if no household member was seen, they shout. Their shouts were simple, screams, funny, sometimes mini poems. Their merchandise was of all sorts and, of course, depending on the season: spring - early vegetables, summer - vegetables, autumn - fruit. Everywhere was heard the voice of the tireless Oltenian. From the seventeenth century, there is a Oltenians slum in Bucharest. Dating from the nineteenth century, was also a street. Oltenians were joined by Albanians, who sold ice cream with vanilla or raspberry, Bulgarians, who had the monopoly of the cultivation and sale of vegetables, the Turks - with sweets and drinks, Jews - with gourmets, coffee, figs, raisins, cake

essences. Eventually, all food was sold on the street. And not only. Each ethnic group had its own market segment: the Greeks, the Bulgarians, Serbs, Turks, Gypsies, Jews ... And it was respected by everyone. A big advantage of strolling trade was that it had no fixed schedule like groceries. Sellers were popping out from all over the place in to boulevards and side streets in the center or at periphery, from the roosters crowing until sunset. Many took merchandise from Main Square (the Unirii Square). Sellers were expected at gates, at entrances to buildings - by housewives or maids sent by the owners with fix money - with fun and joy. Most people knew each other. Romanian urban society did not yet become impersonal..! Peddling was a great relief for all. Because markets were little, the products transport was hardly managed, on to opened roads, with few expensive vehicles. A boon to buyers. They had everything they needed at home. And more, selling on credit was functional, accounting was held with chalk on the door sill of the kitchen: a circle for an oca and one line for a pound ... Other times! We were in the East, we were in the West? These could be the foreigners questions that discovered in Romania the first circle of existence. But not to the Romanians from the cities, who enjoyed life and often leave thoughts pass by.

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- M1a PDFDocument80 pagesM1a PDFTabish KhanNo ratings yet

- Interest Rate Swaptions: DefinitionDocument2 pagesInterest Rate Swaptions: DefinitionAnurag ChaturvediNo ratings yet

- Theme Park Operations & Major PlayersDocument10 pagesTheme Park Operations & Major Playersvitaliskc0% (1)

- Apply Home Loan FormDocument7 pagesApply Home Loan Formrahulgeo05No ratings yet

- Foreign Exchange Risk ManagementDocument28 pagesForeign Exchange Risk Managementanand_awarNo ratings yet

- 2013-14 State Aid Projections (Final Budget)Document88 pages2013-14 State Aid Projections (Final Budget)robertharding22No ratings yet

- Lecture 14 25062022 060915pmDocument37 pagesLecture 14 25062022 060915pmSyeda Maira BatoolNo ratings yet

- Spa Lpfo AndrewDocument11 pagesSpa Lpfo AndrewnashapI100% (1)

- Differences Between Lease and TenancyDocument3 pagesDifferences Between Lease and TenancyQis Balqis RamdanNo ratings yet

- Contractual ProcedureDocument44 pagesContractual Proceduredasun100% (7)

- 28 Comm 308 Final Exam (Winter 2016)Document11 pages28 Comm 308 Final Exam (Winter 2016)TejaNo ratings yet

- Ic38 Q&a-2Document29 pagesIc38 Q&a-2Anonymous O82vX350% (2)

- Jetta A5 January 2010Document10 pagesJetta A5 January 2010billydump100% (1)

- BDO UITFs 2017 PDFDocument4 pagesBDO UITFs 2017 PDFfheruNo ratings yet

- Big Mac IndexDocument43 pagesBig Mac IndexVinayak HalapetiNo ratings yet

- Qualifying Exam - FAR - 1st YearDocument11 pagesQualifying Exam - FAR - 1st YearKristina Angelina ReyesNo ratings yet

- 758x 3ADocument2 pages758x 3ANathan WangNo ratings yet

- Servis Final CompliationDocument37 pagesServis Final CompliationHamza KhanNo ratings yet

- AbbreviationsDocument4 pagesAbbreviationsMert KIRANNo ratings yet

- Spouses Zalamea vs. CA PDFDocument15 pagesSpouses Zalamea vs. CA PDFAira Mae LayloNo ratings yet

- Investment and Decision Analysis For Petroleum ExplorationDocument24 pagesInvestment and Decision Analysis For Petroleum Explorationsandro0112No ratings yet

- Colombia Watch Bank of America June 2023Document13 pagesColombia Watch Bank of America June 2023La Silla VacíaNo ratings yet

- Intl. Finance Test 1 - CompleteDocument6 pagesIntl. Finance Test 1 - CompleteyaniNo ratings yet

- Agriculture Price PolicyDocument58 pagesAgriculture Price PolicyRohit Kumar100% (4)

- Applied-Econ Q1 W5 M5 LDS Market-Structures ALG RTPDocument7 pagesApplied-Econ Q1 W5 M5 LDS Market-Structures ALG RTPHelen SabuquelNo ratings yet

- Solution To Case 12: What Are We Really Worth?Document4 pagesSolution To Case 12: What Are We Really Worth?khalil rebato100% (1)

- Accept Thomson Division Bid to Support Internal Development CostsDocument2 pagesAccept Thomson Division Bid to Support Internal Development Costsutrao100% (2)

- Exchange Rates & Foreign Markets DocumentDocument5 pagesExchange Rates & Foreign Markets DocumentclareNo ratings yet

- Econ IntroDocument9 pagesEcon Introsakura_khyle100% (1)