Professional Documents

Culture Documents

COL

Uploaded by

Tani AngubCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

COL

Uploaded by

Tani AngubCopyright:

Available Formats

TAYAG VS.

BENGUET CONSOLIDATED PRIVATE INTERNATIONAL LAW: Situs of Shares of Stock: domicile of the corporation SUCCESSION: Ancillary Administration: The ancillary administration is proper, whenever a person dies, leaving in a country other than that of his last domicile, property to be administered in the nature of assets of the deceased liable for his individual debts or to be distributed among his heirs. SUCCESSION: Probate: Probate court has authority to issue the order enforcing the ancillary administrators right to the stock certificates when the actual situs of the shares of stocks is in the Philippines. Idonah Slade Perkins, an American citizen who died in New York City, left among others, two stock certificates issued by Benguet Consolidated, a corporation domiciled in the Philippines. As ancillary administrator of Perkins estate in the Philippines, Tayag now wants to take possession of these stock certificates but County Trust Company of New York, the domiciliary administrator, refused to part with them. Thus, the probate court of the Philippines was forced to issue an order declaring the stock certificates as lost and ordering Benguet Consolidated to issue new stock certificates representing Perkins shares. Benguet Consolidated appealed the order, arguing that the stock certificates are not lost as they are in existence and currently in the possession of County Trust Company of New York. ISSUE: Whether or not the order of the lower court is proper The appeal lacks merit. Tayag, as ancillary administrator, has the power to gain control and possession of all assets of the decedent within the jurisdiction of the Philippines. It is to be noted that the scope of the power of the ancillary administrator was, in an earlier case, set forth by Justice Malcolm. Thus: "It is often necessary to have more than one administration of an estate. When a person dies intestate owning property in the country of his domicile as well as in a foreign country, administration is had in both countries. That which is granted in the jurisdiction of decedent's last domicile is termed the principal administration, while any other administration is termed the ancillary administration. The reason for the latter is because a grant of administration does not ex proprio vigore have any effect beyond the limits of the country in which it is granted. Hence, an administrator appointed in a foreign state has no authority in the [Philippines]. The ancillary administration is proper, whenever a person dies, leaving in a country other than that of his last domicile, property to be administered in the nature of assets of the deceased liable for his individual debts or to be distributed among his heirs." Probate court has authority to issue the order enforcing the ancillary administrators right to the stock certificates when the actual situs of the shares of stocks is in the Philippines. It would follow then that the authority of the probate court to require that ancillary administrator's right to "the stock certificates covering the 33,002 shares ... standing in her name in the books of [appellant] Benguet Consolidated, Inc...." be respected is equally beyond question. For appellant is a Philippine corporation owing full allegiance and subject to the unrestricted jurisdiction of local courts. Its shares of stock cannot therefore be considered in any wise as immune from lawful court orders. Our holding in Wells Fargo Bank and Union v. Collector of Internal Revenue finds application. "In the instant case, the actual situs of the shares of stock is in the Philippines, the corporation being domiciled [here]." To the force of

the above undeniable proposition, not even appellant is insensible. It does not dispute it. Nor could it successfully do so even if it were so minded. UNITED AIRLINES, INC., vs. COURT OF APPEALS, ANICETO FONTANILLA, et al. Facts: Private respondent Aniceto Fontanilla purchased from petitioner United Airlines in Manila three (3) "Visit the U.S.A." tickets for himself, his wife and his son. The Fontanillas proceeded to the United States as planned, where they used the first coupon from San Francisco to Washington. On April 24, 1989, Aniceto Fontanilla bought two (2) additional coupons each for himself, his wife and his son from petitioner at its office in Washington Dulles Airport. After paying the penalty for rewriting their tickets, the Fontanillas were issued tickets with corresponding boarding passes with the words "CHECK-IN REQUIRED," for United Airlines Flight No. 1108. The cause of the non-boarding of the Fontanillas on United Airlines Flight No. 1108 makes up the bone of contention of this controversy. The Fontanillas claim that they were denied boarding, that the employees of United Airlines were discourteous, arbitrary and discriminatory. On the other hand, according to United Airlines, the Fontanillas did not initially go to the check-in counter to get their seat assignments for UA Flight 1108. They instead proceeded to join the queue boarding the aircraft without first securing their seat assignments as required in their ticket and boarding passes. Having no seat assignments, the stewardess at the door of the plane instructed them to go to the check-in counter. When the Fontanillas proceeded to the check-in counter, Linda Allen, the United Airlines Customer Representative at the counter informed them that the flight was overbooked. She booked them on the next available flight and offered them denied boarding compensation. Allen vehemently denies uttering the derogatory and racist words attributed to her by the Fontanillas. The incident prompted the Fontanillas to file Civil Case No. 89-4268 for damages before the Regional Trial Court of Makati. The TC ruled in favour of the Petitioner. CA reversed, finding that there was an admission on the part of United Airlines that the Fontanillas did in fact observe the check-in requirement and ruled further that even assuming there was a failure to observe the check-in requirement, United Airlines failed to comply with the procedure laid down in cases where a passenger is denied boarding. Issue: Whether or not respondent court of appeals gravely erred in ruling that private respondents failure to check-in will not defeat his claims because the denied boarding rules were not complied with. Held: The Court does not agree with the conclusion reached by the appellate court that private respondents failure to comply with the check-in requirement will not defeat his claim as the denied boarding rules were not complied with. Notably, the appellate court relied on the Code of Federal Regulation Part on Oversales. The appellate court, however, erred in applying the laws of the United States as, in the case at bar, Philippine law is the applicable law. Although, the contract of carriage was to be performed in the United States, the tickets were purchased through petitioners agent in Manila. It is true that the tickets were "rewritten" in Washington, D.C.

however, such fact did not change the nature of the original contract of carriage entered into by the parties in Manila. The doctrine of lex loci contractus. According to the doctrine, as a general rule, the law of the place where a contract is made or entered into governs with respect to its nature and validity, obligation and interpretation. This has been said to be the rule even though the place where the contract was made is different from the place where it is to be performed, and particularly so, if the place of the making and the place of performance are the same. Hence, the court should apply the law of the place where the airline ticket was issued, when the passengers are residents and nationals of the forum and the ticket is issued in such State by the defendant airline. The law of the forum on the subject matter is Economic Regulations No. 7 as amended by Boarding Priority and Denied Board Compensation of the Civil Aeronautics Board which provides that the check-in requirement be complied with before a passenger may claim against a carrier for being denied boarding: Sec. 5. Amount of Denied Boarding Compensation Subject to the exceptions provided hereinafter under Section 6, carriers shall pay to passengers holding confirmed reserved space and who have presented themselves at the proper place and time and fully complied with the carriers check-in and reconfirmation procedures and who are acceptable for carriage under the Carriers tariff but who have been denied boarding for lack of space, a compensation at the rate of: xxx Plaintiffs fail to realize that their failure to check in, as expressly required in their boarding passes, is they very reason why they were not given their respective seat numbers, which resulted in their being denied boarding. the private respondents were not able to prove that they were subjected to coarse and harsh treatment by the ground crew of united Airlines. Neither were they able to show that there was bad faith on part of the carrier airline. CA decision reversed. CADALIN VS. POEA Borrowing Statute Ex: Sec. 48, Rule on Civil Procedure if by the laws of the State or country where the cause of action arose the action is barred, it is also barred in the Philippines. Facts: Cadalin et al. are Filipino workers recruited by Asia Intl Builders Co. (AIBC), a domestic recruitment corporation, for employment in Bahrain to work for Brown & Root Intl Inc. (BRII) which is a foreign corporation with headquarters in Texas. Plaintiff instituted a class suit with the POEA for money claims arising from the unexpired portion of their employment contract which was prematurely terminated. They worked in Bahrain for BRII and they filed the suit after 1 yr. from the termination of their employment contract. As provided by Art. 156 of the Amiri Decree aka as the Labor Law of the Private Sector of Bahrain: a claim arising out of a contract of employment shall not be actionable after the lapse of 1 year from the date of the expiry of the contract, it appears that their suit has prescribed. Plaintiff contends that the prescription period should be 10 years as provided by Art. 1144 of the Civil Code as their claim arise from a violation of a contract. The POEA Administrator holds that the 10 year period of prescription should be applied but the NLRC provides a different view asserting that Art 291 of the Labor Code of the Phils with a 3 years prescription period should be applied. The Solicitor General expressed his personal point of view that the 1 yr period provided by the Amiri Decree should be applied.

Ruling: The Supreme Court held that as a general rule a foreign procedural law will not be applied in our country as we must adopt our own procedural laws. EXCEPTION: Philippines may adopt foreign procedural law under the Borrowing Statute such as Sec. 48 of the Civil Procedure Rule stating if by the laws of the State or country where the cause of action arose the action is barred, it is also barred in the Philippines. Thus, Bahrain law must be applied. However, the court contends that Bahrains law on prescription cannot be applied because the court will not enforce any foreign claim that is obnoxious to the forums public policy and the 1 yr. rule on prescription is against public policy on labor as enshrined in the Phils. Constitution. The court ruled that the prescription period applicable to the case should be Art 291 of the Labor Code of the Phils with a 3 years prescription period since the claim arose from labor employment.

PAKISTAN INTL AIRLINES vs. OPLE (1990) FACTS: Pakistan International Airlines executed in Manila 2 separate contracts of employment which provided that PIA reserves the right to terminate the agreement at anytime by giving the employee notice in writing 1 month before the intended date of termination and that the governing law shall be the laws of Pakistan and venue for actions is Karachi courts. PIA terminated the employment of the 2 Filipinas who filed complaint for illegal dismissal. ISSUE: WON Pakistani law is the governing law. HELD: 1. Public Policy: No. This contractual provision cannot be invoked to prevent the application of Philippine labor laws and regulations to the subject matter of this case. EE-ER relationship is much affected with public interest and that the otherwise applicable Philippine laws and regulations cannot be rendered illusory by the parties by agreeing upon some other law to govern their relationship. 2. Substantive Contacts/Most significant relationship: Karachi courts cannot be the sole venue for the settlement of disputes. Contract was executed and performed in the Philippines. Petitioner is a corp. doing business in the Philippines and private respondents are citizens therein. 3. PIA did not prove Pakistani law, thus, it is presumed to be the same as Philippine law. Huntinghon vs. Attrill, 146 U.S. 657 (1892) Testate Estate of Amos G. Bellis et al. vs. Edward Bellis FACTS: Amos G. Bellis, born in Texas, was "a citizen of the State of Texas and of the United States."

By his first wife, Mary E. Mallen, whom he divorced, he had five legitimate children: Edward A. Bellis, George Bellis (who pre-deceased him in infancy), Henry A. Bellis, Alexander Bellis and Anna Bellis Allsman; by his second wife, Violet Kennedy, who survived him, he had three legitimate children: Edwin G. Bellis, Walter S. Bellis and Dorothy Bellis; and finally, he had three illegitimate children: Amos Bellis, Jr., Maria Cristina Bellis and Miriam Palma Bellis. Amos G. Bellis executed a will in the Philippines, in which he directed that after all taxes, obligations, and expenses of administration are paid for, his distributable estate should be divided, in trust, in the following order and manner: (a) $240,000.00 to his first wife, Mary E. Mallen; (b) P120,000.00 to his three illegitimate children, Amos Bellis, Jr., Maria Cristina Bellis, Miriam Palma Bellis, or P40,000.00 each and (c) after the foregoing two items have been satisfied, the remainder shall go to his seven surviving children by his first and second wives, namely: Edward A. Bellis, Henry A. Bellis, Alexander Bellis and Anna Bellis Allsman, Edwin G. Bellis, Walter S. Bellis, and Dorothy E. Bellis, in equal shares.1wph1.t Subsequently, Amos G. Bellis died a resident of San Antonio, Texas, U.S.A. His will was admitted to probate in the Court of First Instance of Manila. The People's Bank and Trust Company, as executor of the will, paid all the bequests therein. It submitted and filed its "Executor's Final Account, Report of Administration and Project of Partition". In the project of partition, the executor pursuant to the "Twelfth" clause of the testator's Last Will and Testament divided the residuary estate into seven equal portions for the benefit of the testator's seven legitimate children by his first and second marriages. Cristina Bellis and Miriam Palma Bellis filed their respective oppositions to the project of partition on the ground that they were deprived of their legitimes as illegitimate children and, therefore, compulsory heirs of the deceased. Amos Bellis, Jr. interposed no opposition despite notice to him. The lower court issued an order overruling the oppositions and approving the executor's final account, report and administration and project of partition. Relying upon Art. 16 of the Civil Code, it applied the national law of the decedent, which in this case is Texas law, which did not provide for legitimes. ISSUE: WHETHER OR NOT IT IS TEXAS LAW THAT IS APPLICABLE AND NOT PHILIPPINE LAW. RULING: The doctrine of renvoi IS NOT DISCUSSED by the parties in this case anyway it is not applicable in the case at bar. Said doctrine is usually pertinent where the decedent is a national of one country, and a domicile of another. In the present case, it is not disputed that the decedent was both a national of Texas and a domicile thereof at the time of his death. YES, TEXAS LAW IS THE APPLICABLE LAW. Article 16, par. 2, and Art. 1039 of OUR Civil Code, render applicable the national law of the decedent, in intestate or testamentary successions, with regard to four items: (a) the order of succession; (b) the amount of successional rights; (e) the intrinsic validity of the provisions of the will; and (d) the capacity to succeed. They provide that ART. 16. Real property as well as personal property is subject to the law of the country where it is situated.

However, intestate and testamentary successions, both with respect to the order of succession and to the amount of successional rights and to the intrinsic validity of testamentary provisions, shall be regulated by the national law of the person whose succession is under consideration, whatever may he the nature of the property and regardless of the country wherein said property may be found. ART. 1039. Capacity to succeed is governed by the law of the nation of the decedent. The parties admit that the decedent, Amos G. Bellis, was a citizen of the State of Texas, U.S.A., and that under the laws of Texas, there are no forced heirs or legitimes. Accordingly, since the intrinsic validity of the provision of the will and the amount of successional rights are to be determined under Texas law, the Philippine law on legitimes cannot be applied to the testacy of Amos G. Bellis. ZALAMEA vs. CA FACTS: Petitioners- purchased three (3) airline tickets from the Manila agent of respondent TransWorld Airlines, Inc. (TWA) for a flight from NY to LA on June 6, 1984. The tickets of petitioners-spouses were discounted while that of their daughter was a full fare ticket. All three tickets represented confirmed reservations which was reconfirmed while they were in NY already. On the appointed date, petitioners were placed on the wait-list because the number of passengers who had checked in before them had already taken all the seats available on the flight. Passengers holding full fare tickets were prioritized. Mr. Zalamea was holding his daughters ticket. As a result, he was allowed to board while his wife and daughter were denied boarding. Mrs. Zalamea and her daughter purchased tickets with American Airlines since TWA cannot accommodate them in the next flight because it is still fully booked. Upon their arrival in the Philippines, petitioners filed an action for damages based on breach of contract of air carriage before the RTC, which ruled in favor of the petitioners. On appeal, Court of Appeals held that moral damages are recoverable in a damage suit predicated upon a breach of contract of carriage only where there is fraud or bad faith. Since it is a matter of record that overbooking of flights is a common and accepted practice of airlines in the United States and is specifically allowed under the Code of Federal Regulations by the Civil Aeronautics Board, no fraud nor bad faith could be imputed on TWA. Further, it ruled that a confirmed reservation may be denied accommodation on an overbooked flight. It also held that there was no bad faith in placing petitioners in the wait-list along with forty-eight (48) other passengers where full-fare first class tickets were given priority over discounted tickets. Not satisfied with the decision, petitioners raised the case on petition for review on certiorari and alleged the following errors committed by CA. Among others, petitioners contend that the U.S. law or regulation allegedly authorizing overbooking has never been proved. Foreign laws do not prove themselves nor can the courts take judicial notice of them. Like any other fact, they must be alleged and proved. Written law may be evidenced by an official publication thereof or by a copy attested by the officer having the legal custody of the record, or by his deputy, and accompanied with a certificate that such officer has custody. The certificate may be made by a secretary of an embassy or legation, consul general, consul, vice-consul, or consular agent or by any officer in the foreign service of the Philippines stationed in the foreign country in which the record is kept, and authenticated by the seal of his office. Respondent TWA relied solely on the statement of Ms. Gwendolyn Lather, its customer service agent that the Code of Federal Regulations of the Civil Aeronautics Board allows overbooking. Aside from said statement, no official publication of said code was presented as evidence.

RULING: GRANTED. CAs finding that overbooking is specifically allowed by the US Code of Federal Regulations has no basis in fact. Even if the claimed U.S. Code of Federal Regulations does exist, the same is not applicable to the case at bar in accordance with the principle of lex loci contractus which require that the law of the place where the airline ticket was issued should be applied by the court where the passengers are residents and nationals of the forum and the ticket is issued in such State by the defendant airline. 8 Since the tickets were sold and issued in the Philippines, the applicable law in this case would be Philippine law. Existing jurisprudence explicitly states that overbooking amounts to bad faith, entitling the passengers concerned to an award of moral damages. Even on the assumption that overbooking is allowed, respondent TWA is still guilty of bad faith in not informing its passengers beforehand that it could breach the contract of carriage even if they have confirmed tickets if there was overbooking. Respondent TWA should have incorporated stipulations on overbooking on the tickets issued or to properly inform its passengers about these policies so that the latter would be prepared for such eventuality or would have the choice to ride with another airline. CA erred in not ordering the refund of the American Airlines tickets purchased and used by petitioners Suthira and Liana. The evidence shows that petitioners Suthira and Liana were constrained to take the American Airlines flight to Los Angeles not because they "opted not to use their TWA tickets on another TWA flight" but because respondent TWA could not accommodate them either on the next TWA flight which was also fully booked. Garcia vs. Recio, G.R. No. 138322, October 2, 2001 Facts: Article 26; The respondent, Rederick Recio, a Filipino was married to Editha Samson, an Australian citizen, in Rizal in 1987. They lived together as husband and wife in Australia. In 1989, the Australian family court issued a decree of divorce supposedly dissolving the marriage. In 1992, respondent acquired Australian citizenship. In 1994, he married Grace Garcia, a Filipina, herein petitioner, in Cabanatuan City. In their application for marriage license, respondent was declared as single and Filipino. Since October 1995, they lived separately, and in 1996 while inAustralia, their conjugal assets were divided. In 1998, petitioner filed Complaint for Declaration of Nullity of Marriage on the ground of bigamy, claiming that she learned of the respondents former marriage only in November. On the other hand, respondent claims that he told petitioner of his prior marriage in 1993, before they were married. Respondent also contended that his first marriage was dissolved by a divorce a decree obtained in Australia in 1989 and hence, he was legally capacitated to marry petitioner in 1994. The trial court declared that the first marriage was dissolved on the ground of the divorce issued in Australia as valid and recognized in the Philippines. Hence, this petition was forwarded before the Supreme Court. Issue: Whether or not respondent has legal capacity to marry Grace Garcia. Ruling: In mixed marriages involving a Filipino and a foreigner, Article 26 of the Family Code allows the former to contract a subsequent marriage in case the divorce is validly obtained abroad by the alien spouse capacitating him or her to remarry. A divorce obtained abroad by two aliens, may be recognized in the Philippines, provided it is consistent with their respective laws. Therefore, before our courts can recognize a foreign divorce, the party pleading it must prove the divorce as a fact and demonstrate its conformity to the foreign law allowing it. In this case, the divorce decree between the respondent and Samson appears to be authentic, issued by an Australian family court. Although, appearance is not sufficient, and compliance with the rules on evidence regarding alleged foreign laws must be demonstrated, the decree was admitted on account of petitioners failure to object properly because he objected to the fact that it was not

registered in the Local Civil Registry of Cabanatuan City, not to its admissibility. Respondent claims that the Australian divorce decree, which was validly admitted as evidence, adequately established his legal capacity to marry under Australian law. Even after the divorce becomes absolute, the court may under some foreign statutes, still restrict remarriage. Respondent also failed to produce sufficient evidence showing the foreign law governing his status. Together with other evidences submitted, they dont absolutely establish his legal capacity to remarry. Asiavest Merchant Bankers vs. Court of Appeals G.R. No. 110263, July 20, 2001 FACTS: The petitioner Asiavest Merchant Bankers (M) Berhad is a corporation organized under the laws of Malaysia Private respondent Philippine National Construction Corporation is a corporation duly incorporated and existing under Philippine laws. In 1983, petitioner initiated a suit for collection against private respondent before the High Court of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur. Petitioner sought to recover the indemnity of the performance bond it had put up in favor of private respondent to guarantee the completion of the Felda Project and the nonpayment of the loan it extended to Asiavest-CDCP Sdn. Bhd. for the completion of Paloh Hanai and Kuantan By Pass; Project. On September 13, 1985, the High Court of Malaya (Commercial Division) rendered judgment in favor of the petitioner and against the private respondent The private respondent was asked to pay 5,108,290.23 Ringgits Following unsuccessful attempts to secure payment from private respondent under the judgment, petitioner initiated on September 5, 1988 the complaint before Regional Trial Court of Pasig, Metro Manila, to enforce the judgment of the High Court of Malaya The RTC of Manila and the CA denied the motion for lack of want of jurisdiction

ISSUE: Whether or not the Malaysian High Court acquired jurisdiction over the PNCC ot the private respondent. Contentions of Private Respondent: (more of the rules of procedure) 1. The Malaysian High Court did not serve the summons to the right persons a. The summons was sent to the accountant of the PNCC, Cora Deala; she is not authorized to receive the summons for and in behalf of the private respondent. And that there is no lawyer who will defend or act in behalf of the private respondent a. According to Abelardo, the private respondents executive secretary said that there is no resolution granting or authorizing Allen and Glendhill (the said to be lawyers of the company) to admit all the claims of the petitioner. That the decision of the Malaysian High Court is tainted with fraud and clear mistake of fact/law; since there is no statement of facts and law given which the award is given in favor of the petitioner.

2.

3.

Held: Petition Granted. The Malaysian High Court acquired jurisdiction over PNCC due to the following ground: 1. Due to the fact that the rules of procedure (such as those serving of summons) are governed by the lex fori or the internal law forumwhich is in this case is Malaysia a. it is the procedural law of Malaysia where the judgment was rendered that determines the validity of the service of court process on private respondent as well as other matters raised by it. i. Since the burden of proof of showing that there are irregularities in the serving of summons as to the procedural rules of the Malaysian high court should be shouldered by the private respondents; however, the private respondent failed to show or give

2.

3.

proof in the said irregularities therefore the PRESUMPTION of validity and regularity of service of summons and the decision rendered by the High Court of Malaya should stand. On the matter of alleged lack of authority of the law firm of Allen and Gledhill to represent private respondent, not only did the private respondent's witnesses admit that the said law firm of Allen and Gledhill were its counsels in its transactions in Malaysia. a. but of greater significance is the fact that petitioner offered in evidence relevant Malaysian jurisprudence to the effect that i. it is not necessary under Malaysian law for counsel appearing before the Malaysian High Court to submit a special power of attorney authorizing him to represent a client before said court, ii. that counsel appearing before the Malaysian High Court has full authority to compromise the suit iii. that counsel appearing before the Malaysian High Court need not comply with certain pre-requisites as required under Philippine law to appear and compromise judgments on behalf of their clients before said court. On the ground that collusion, fraud and, clear mistake of fact and law tainted the judgment of the High Court of Malaya, no clear evidence of the same was adduced or shown. Since the burden of proof again should be shouldered by the private respondent a. As aforestated, the lex fori or the internal law of the forum governs matters of remedy and procedure. i. Considering that under the procedural rules of the High Court of Malaya, a valid judgment may be rendered even without stating in the judgment every fact and law upon which the judgment is based, then the same must be accorded respect and the courts in the jurisdiction cannot invalidate the judgment of the foreign court simply because our rules provide otherwise.

INTERCONTINENTAL HOTELS CORPORATION, vs. JACK GOLDEN Facts: Plaintiff is the owner and operator of a government-licensed gambling casino in Puerto Rico, which seeks to recover the sum of $12,000 evidenced by defendant's check and I. O. U.s given in payment of gambling debts incurred in Puerto Rico. The Transaction occurred in Puerto Rico where the plaintiff is licensed under the laws of Puerto Rico to conduct said gambling casino. The Supreme Court, New York County entered judgment for plaintiff, and defendant appealed. The Supreme Court, Appellate Division, First Judicial Department, reversed the judgment and dismissed the complaint, and a further appeal was taken. Issue: Whether or not the New York courts may refuse to enforce a foreign right, though valid where acquired, on the ground that its enforcement is contrary to (the public) policy of the forum Ruling: Public policy did not forbid New York court to enforce gambling obligations validly entered into in Commonwealth of Puerto Rico and enforceable under Puerto Rican law.

An indebtedness such as that incurred by the defendant, which is legal where incurred, and sued on here is enforceable in our courts. The fact that New York has no law similar to that of Puerto Rico, legalizing gambling when conducted in a licensed gambling casino, does not preclude the enforcement of plaintiff's claim in New York. "Unless there is something immoral or fundamentally unjust in the arrangement, there is no policy of our State which forbids the enforcement of contracts or agreements which are legal according to the place of performance" However, as was pointed out by Mr. Presiding Justice Botein in Miltenberg & Samton v. Mallor (1 A.D.2d 458, 460) "Sometimes a transaction is so plainly prejudicial to the public good, so clearly repulsive to every concept of morality and fair dealing, that a court need not look further to ascertain whether it is also proscribed expressly by some statute. * * * 'In many of its aspects the term "public policy" is but another name for public sentiment'". In view of present-day conditions, including the licensing of bingo by the State of New York, and the legalizing of pari-mutuel betting (N. Y. Const., art. I, ? 9), gambling may not be said to be such a heinous offense or so clearly repulsive to every concept of morality that it would be contrary to public policy to enforce a gambling debt which was legally incurred, as is the case here. Judgment is accordingly awarded to the plaintiff in the sum of $12,000, with interest as demanded in the complaint.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- New Holland TM165 Shuttle Command (Mechanical Transmission) PDFDocument44 pagesNew Holland TM165 Shuttle Command (Mechanical Transmission) PDFElena DNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- 1000.01 Good Documentation PracticesDocument13 pages1000.01 Good Documentation PracticescipopacinoNo ratings yet

- In Re Farber (State v. Jascalevich) 78 N.J. 259, 394 A.2d 330, Cert. Denied, 439 U.S. 997 (1978)Document30 pagesIn Re Farber (State v. Jascalevich) 78 N.J. 259, 394 A.2d 330, Cert. Denied, 439 U.S. 997 (1978)Tani AngubNo ratings yet

- In Re Farber (State v. Jascalevich) 78 N.J. 259, 394 A.2d 330, Cert. Denied, 439 U.S. 997 (1978)Document30 pagesIn Re Farber (State v. Jascalevich) 78 N.J. 259, 394 A.2d 330, Cert. Denied, 439 U.S. 997 (1978)Tani AngubNo ratings yet

- Remedial LawDocument185 pagesRemedial LawTani Angub100% (2)

- Umali vs. Estanislao - DigestDocument1 pageUmali vs. Estanislao - DigestTani AngubNo ratings yet

- Umali vs. Estanislao - DigestDocument1 pageUmali vs. Estanislao - DigestTani AngubNo ratings yet

- Umali vs. Estanislao - DigestDocument1 pageUmali vs. Estanislao - DigestTani AngubNo ratings yet

- Hydrostatic Pressure Test Safety ChecklistDocument3 pagesHydrostatic Pressure Test Safety ChecklistJerry Faria60% (5)

- Lacoste vs. HernandezDocument3 pagesLacoste vs. HernandezTani AngubNo ratings yet

- Common Metallurgical Defects in Grey Cast IronDocument9 pagesCommon Metallurgical Defects in Grey Cast IronRolando Nuñez Monrroy100% (1)

- Cable 3/4 Sleeve Sweater: by Lisa RichardsonDocument3 pagesCable 3/4 Sleeve Sweater: by Lisa RichardsonAlejandra Martínez MartínezNo ratings yet

- Case DigestsDocument2 pagesCase DigestsTani AngubNo ratings yet

- Case DigestsDocument2 pagesCase DigestsTani AngubNo ratings yet

- Notes in Train Law PDFDocument11 pagesNotes in Train Law PDFJanica Lobas100% (1)

- imageRUNNER+ADVANCE+C5051-5045-5035-5030 Parts CatalogDocument268 pagesimageRUNNER+ADVANCE+C5051-5045-5035-5030 Parts CatalogDragos Burlacu100% (1)

- Asia Brewery vs. Court of AppealsDocument2 pagesAsia Brewery vs. Court of AppealsTani AngubNo ratings yet

- Agan Vs PIATCO DigestedDocument5 pagesAgan Vs PIATCO DigestedTani AngubNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Food Quality Control ProgrammeDocument75 pagesChapter 1 - Food Quality Control ProgrammeFattah Abu Bakar100% (1)

- McDonald's vs. MacJoyDocument2 pagesMcDonald's vs. MacJoyTani AngubNo ratings yet

- #54 Arroyo vs. VasquezDocument7 pages#54 Arroyo vs. VasquezTani AngubNo ratings yet

- #80 Maxey vs. CADocument8 pages#80 Maxey vs. CATani AngubNo ratings yet

- Consolidated DigestsDocument100 pagesConsolidated DigestsTani AngubNo ratings yet

- 3 CasesDocument5 pages3 CasesTani AngubNo ratings yet

- Chamoy & Beryl Digested Cases Republic v. CA and Molina Republic v. CA and Molina GR 108763, 13 February 1997 FactsDocument10 pagesChamoy & Beryl Digested Cases Republic v. CA and Molina Republic v. CA and Molina GR 108763, 13 February 1997 FactsTani AngubNo ratings yet

- Godines vs. MoranDocument2 pagesGodines vs. MoranTani AngubNo ratings yet

- (Civil) Cases-20100703 - 4 CasesDocument15 pages(Civil) Cases-20100703 - 4 CasesTani AngubNo ratings yet

- Wing vs. Ahmad AbubakarDocument2 pagesWing vs. Ahmad AbubakarKate PunzalanNo ratings yet

- VATDocument17 pagesVATTani AngubNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court: Principal P 32,188,723.07 Interest 2,763,088.93 Penalty Charges 5,568.649.09Document4 pagesSupreme Court: Principal P 32,188,723.07 Interest 2,763,088.93 Penalty Charges 5,568.649.09Noelle Therese Gotidoc VedadNo ratings yet

- CaseDocument61 pagesCaseTani AngubNo ratings yet

- CaseDocument61 pagesCaseTani AngubNo ratings yet

- CaseDocument61 pagesCaseTani AngubNo ratings yet

- First AssignmentDocument1 pageFirst AssignmentTani AngubNo ratings yet

- Gaanan vs. IacDocument5 pagesGaanan vs. IacTani AngubNo ratings yet

- I'm Gonna Love YouDocument1 pageI'm Gonna Love YouTani AngubNo ratings yet

- Funny AcronymsDocument6 pagesFunny AcronymsSachinvirNo ratings yet

- Marketing Theory and PracticesDocument4 pagesMarketing Theory and PracticesSarthak RastogiNo ratings yet

- The Development of Silicone Breast Implants That Are Safe FoDocument5 pagesThe Development of Silicone Breast Implants That Are Safe FomichelleflresmartinezNo ratings yet

- Compatibility Matrix For Cisco Unified Communications Manager and The IM and Presence Service, Release 12.5 (X)Document31 pagesCompatibility Matrix For Cisco Unified Communications Manager and The IM and Presence Service, Release 12.5 (X)Flavio AlonsoNo ratings yet

- Submersible Sewage Ejector Pump: Pump Installation and Service ManualDocument8 pagesSubmersible Sewage Ejector Pump: Pump Installation and Service Manualallen_worstNo ratings yet

- Chap 4 Safety Managment SystemDocument46 pagesChap 4 Safety Managment SystemABU BEBEK AhmNo ratings yet

- Template For Public BiddingDocument3 pagesTemplate For Public BiddingFederico DomingoNo ratings yet

- Dy DX: NPTEL Course Developer For Fluid Mechanics Dr. Niranjan Sahoo Module 04 Lecture 33 IIT-GuwahatiDocument7 pagesDy DX: NPTEL Course Developer For Fluid Mechanics Dr. Niranjan Sahoo Module 04 Lecture 33 IIT-GuwahatilawanNo ratings yet

- Digest of Agrarian From DAR WebsiteDocument261 pagesDigest of Agrarian From DAR WebsiteHuzzain PangcogaNo ratings yet

- SYLVANIA W6413tc - SMDocument46 pagesSYLVANIA W6413tc - SMdreamyson1983100% (1)

- ISDM - Lab Sheet 02Document4 pagesISDM - Lab Sheet 02it21083396 Galappaththi S DNo ratings yet

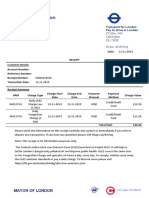

- Transport For London Pay To Drive in London: PO Box 344 Darlington Dl1 9qe TFL - Gov.uk/drivingDocument1 pageTransport For London Pay To Drive in London: PO Box 344 Darlington Dl1 9qe TFL - Gov.uk/drivingDanyy MaciucNo ratings yet

- 'G' by Free Fall Experiment Lab ReportDocument3 pages'G' by Free Fall Experiment Lab ReportRaghav SinhaNo ratings yet

- Megohmmeter: User ManualDocument60 pagesMegohmmeter: User ManualFlavia LimaNo ratings yet

- Assignment3 (Clarito, Glezeri BSIT-3A)Document9 pagesAssignment3 (Clarito, Glezeri BSIT-3A)Jermyn G EvangelistaNo ratings yet

- Fss Operators: Benchmarks & Performance ReviewDocument7 pagesFss Operators: Benchmarks & Performance ReviewhasanmuskaanNo ratings yet

- Validation TP APPO R12Document3 pagesValidation TP APPO R12Suman GopanolaNo ratings yet

- Hyundai Monitor ManualDocument26 pagesHyundai Monitor ManualSamNo ratings yet

- PDF 24Document8 pagesPDF 24Nandan ReddyNo ratings yet

- Experiment No 9 - Part1Document38 pagesExperiment No 9 - Part1Nipun GosaiNo ratings yet

- Nilfisck SR 1601 DDocument43 pagesNilfisck SR 1601 DGORDNo ratings yet

- Instruction Manual Series 880 CIU Plus: July 2009 Part No.: 4416.526 Rev. 6Document44 pagesInstruction Manual Series 880 CIU Plus: July 2009 Part No.: 4416.526 Rev. 6nknico100% (1)