Professional Documents

Culture Documents

265.fullthe Impact of Psychosocial Work Conditions On Attempted and Completed Suicide Among Western Canadian Sawmill Workers

Uploaded by

ravibunga4489Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

265.fullthe Impact of Psychosocial Work Conditions On Attempted and Completed Suicide Among Western Canadian Sawmill Workers

Uploaded by

ravibunga4489Copyright:

Available Formats

Scandinavian http://sjp.sagepub.

com/ Public Health Journal of

The impact of psychosocial work conditions on attempted and completed suicide among western Canadian sawmill workers

Aleck Ostry, Stefania Maggi, James Tansey, James Dunn, Ruth Hershler, Lisa Chen, A.M. Louie and Clyde Hertzman Scand J Public Health 2007 35: 265 DOI: 10.1080/14034940601048091 The online version of this article can be found at: http://sjp.sagepub.com/content/35/3/265

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Scandinavian Journal of Public Health can be found at: Email Alerts: http://sjp.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://sjp.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://sjp.sagepub.com/content/35/3/265.refs.html

>> Version of Record - May 1, 2007 What is This?

Downloaded from sjp.sagepub.com by RAVI BABU BUNGA on October 29, 2011

Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 2007; 35: 265271

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

The impact of psychosocial work conditions on attempted and completed suicide among western Canadian sawmill workers

ALECK OSTRY1, STEFANIA MAGGI2, JAMES TANSEY3, JAMES DUNN4, RUTH HERSHLER1, LISA CHEN1, A. M. LOUIE1 & CLYDE HERTZMAN1

1

The University of British Columbia, 2Thompson Rivers University, 3Oxford University, and 4St Michaels Hospital

Abstract Background: Using a large cohort of western Canadian sawmill workers (n528,794), the association between psychosocial work conditions and attempted and completed suicide was investigated. Methods: Records of attempted and completed suicide were accessed through a provincial hospital discharge registry to identify cases that were then matched using a nested case control method. Psychosocial work conditions were estimated by expert raters using the demandcontrol model. Univariate and multivariate conditional logistic regression was used to estimate the association between work conditions and suicide. Results: In multivariate models, controlling for sociodemographic (marital status, ethnicity) and occupational confounders (job mobility and duration), low psychological demand was associated with increased odds for completed suicide, and low social support was associated with increased odds for attempted suicides. Conclusions: This study indicates that workers with poor psychosocial working conditions may be at increased risk of both attempted and completed suicide.

Key Words: Attempted suicide, Canada, completed suicide, psychosocial work conditions, sawmill workers

Introduction National suicide rates differ widely. They tend to be higher in industrialized developed nations and, in Europe, the highest suicide rates are found in Russia and the Baltic states. Nordic and Eastern European countries also have somewhat higher suicide rates, while the southern parts of Europe have comparatively low rates. America and Asia generally have lower rates than most of the European countries [1]. While in many industrialized countries suicide is one of the three leading causes of death among young adults, recent investigations on suicide have focused mainly on adolescents and the elderly [1]. However, the risk of suicide peaks at ages 45 to 54 (declining at ages 55 to 74, and increasing again at ages over 75), both in Canada and worldwide, indicating that working-age populations are at risk of suicide [2,3].

In some nations suicide rates among employed working-age populations are increasing [5,6]. For example, in Japan, in 1999, sharp increases in the suicide rate occurred particularly among men in their forties and fifties and these appear mainly to have been due to economic reasons [6]. In Japan, the links between overwork [7] and suicide (karojisatsu work-related suicide) [8] have been investigated mainly among employed men. For example, in a recent investigation Amagasa and colleagues [8] analyzed 22 insurance and legal reports filed by psychiatrists on employee suicides that were related to heavy workloads. Contributing causes in most of these suicides, as determined by consensus of a clinical epidemiologist and two psychiatrists, included: experience of personnel changes (19 cases), such as a promotion or transfer, low social support (18), high psychological demand (18), low decision latitude (17), and long working hours (19) cases. The authors

Correspondence: Aleck Ostry, Department of Health Care and Epidemiology, 5804 Fairview Avenue, Vancouver BC, V6T 1Z3 Canada. Tel: 604- 822-5872. Fax: 604- 822-4994. E-mail: ostry@interchange.ubc.ca (Accepted 4 October 2006) ISSN 1403-4948 print/ISSN 1651-1905 online/07/030265-7 # 2007 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/14034940601048091

Downloaded from sjp.sagepub.com by RAVI BABU BUNGA on October 29, 2011

266

A. Ostry et al. Material and methods Participants This study is based on a cohort of male sawmill workers for whom we have obtained data on history of unemployment, job mobility, psychosocial work conditions, health outcomes, and death records. The cohort was gathered, originally, in 1988 in order to conduct an occupational study on the effects of chlorophenol anti-sapstain exposure among British Columbia sawmill workers. Fourteen medium to large size (150450 workers each) sawmills located mainly in British Columbian coastal communities were identified. For the original study, research assistants screened personnel records (i.e. the file for each employee that contained personal information such as birth date, marital status etc. and a record of job start and end dates and job titles held while working at the mill) at each of the study mills to identify workers employed, for at least one year, in one of these mills at any time between 1950 and 1988. This cohort was updated in 1998 to extend work histories for cohort members and to add new cohort members who were hired between 1988 and 1998. A cohort of 28,794 male workers was enumerated consisting of eligible cohort members who worked at a study mill between 1950 and 1998. Personal identifying information for eligible workers (i.e. names, social insurance numbers, date of birth) and complete job-history records (consisting of job title and start and end dates for each job held by each worker) were abstracted from personnel records. A complete description of methods used to assemble this cohort can be found in Hertzman et al. [29]. From personnel records, we obtained age, marital status (at time of hiring), and ethnic status (classified as Caucasian, Sikh, or Chinese), duration of employment at a study mill, occupational status (manager, tradesman, skilled worker, unskilled worker), and number of episodes of unemployment. At each job change, mobility was characterized as upward, downward, or stable depending on whether the new job was respectively for more pay, less pay, or the same pay as the previous job. Exposure variables A shortened version of Karaseks Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) [30] was used to measure exposure in terms of control, psychological demand, physical demand, and co-worker social support (see Appendix). Retrospective estimates of job control, demands, noise, and social support were obtained in two ways:

concluded that long working hours, heavy workloads, and low social support may cause depression, which can lead to suicide. While job strain was not implicated in suicides in this rather small-scale study, in a comprehensive review of the causes of karoshi (death from overwork) in Japan, Nishiyama and Johnson [7] postulated job strain as the primary cause. However, despite these suggestive Japanese findings as well as strong evidence highlighting the link between unemployment and suicide, particularly among men [4,922], few studies have investigated the link between working conditions and suicide among employed workers [2328]. Only one prospective cohort study has investigated the relationship between psychosocial work conditions and suicide [2]). In this study, a large US cohort of female nurses (n594,110) was followed up for 14 years and their self-reported stress at work and at home was estimated using a four-point scale: minimal, light, high, and severe. After adjustment for age, smoking, coffee consumption, alcohol intake, and marital status, relative risks (RR) were elevated among women reporting both severe work stress (RR51.9, 95% CI 0.84.7), and high exposure to both home and work stress demonstrated statistically significant positive association with completed suicide (RR54.9, 95% CI 1.417.0). The hypothesis that psychosocial working conditions are a significant determinant of health (including mental health), has been investigated using Robert Karaseks demandcontrol model [3,4]. According to this model, people who perform jobs with high psychological demand and low control (high-strain jobs) are more likely to develop symptoms of psychological stress than those working in jobs with low demand and high control. As well, according to Karaseks model, workers exposed to low psychological demand and low control (so-called passive jobs) are at particular risk of developing a sense of learned hopelessness, which is one of the strongest predictors of completed suicide [29 31]. The purpose of this investigation was to extend the applications of the demandcontrol model to a study of the association between psychosocial working conditions in a cohort of Western Canadian sawmill workers in relation to attempted and completed suicide. Specifically, we tested the hypothesis that sawmill workers in jobs with low control and low psychological demand were at the greatest risk of attempted and completed suicide.

Downloaded from sjp.sagepub.com by RAVI BABU BUNGA on October 29, 2011

Psychosocial work conditions and suicide among sawmill workers 1. Four job evaluators (two union and two management) with over 35 years experience in the BC sawmill industry completed a shortened version of Karaseks Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) 30) retrospectively estimating all basic job titles in the sawmill industry prior to 1975 (for a complete description of these methods see Ostry et al. [31]). 2. A panel of senior workers in each study sawmill was randomly selected and asked to complete the shortened version of the JCQ for basic job titles in their sawmill for the time periods 1975 to 1985, and 1985 to 1998 (for a complete description of these methods see Ostry et al. [32]). Estimates from job evaluators (for the period prior to 1975) and senior workers (for the period between 1975 and 1998) for control, psychological demand, physical demand, social support, and noise were then linked to the job history database in the sawmill cohort. In addition, exposure in terms of job mobility, unemployment experience, and exposure to control, psychological demand, physical demand, social support, and noise was determined for each year a worker was employed at a study sawmill. Exposures were based on the job title held at a given time by a worker and so were linked to the job history file for each worker on the basis of his job title. Outcome variables The cohort of 28,794 sawmill workers with information on work stress obtained by job evaluators and senior workers was probabilistically linked to the British Columbia Linked Health Database (BCLHDB) [30]. The BCLHDB consists of person-specific, longitudinal records on all residents of British Columbia. These files contain data on physician services, hospital discharges, drug prescriptions, long-term care services, mental health client registry, Work Compensation Board records, income assistance records, cancer incidence, deaths, cause of death, and births from 1985 to the present. The records are housed at the University of British Columbias Center for Health Services and Policy Research (CHSPR) and are managed jointly by the Center, the University, and the Ministry of Health. A Data Access Subcommittee consisting of health ministry personnel, staff from the BC Ministry of Information and Privacy, and CHSPR has been established to handle requests for linkage to the BCLHDB and to ensure that such requests meet scientific and ethical standards, are in the public interest, and conform with British Columbias

267

Freedom on Information and Protection of Privacy Act. Each file is stored separately but has been indexed with an individual service-recipient-specific code so that the records of groups of individuals can be linked across files for specific research projects. In British Columbia, complete hospital discharge records are available through the BCLHDB, including ICD9 codes for each diagnosis. A suicide case was defined as anyone with a hospital discharge or death record coded with ICD9 codes 950 to 950.9. We divided suicide cases into two dependent variables: suicide attempts (one or more) and completed suicides. From the hospital discharge database we were able to identify any suicide case (completed and attempted) that occurred between 1 January 1985 and 31 March 2001. Between 1952 and 1985, 162 cohort members completed suicide and between 1985 and 2001, 127 workers attempted suicide. Sociodemographic and occupational characteristics of completed and attempted suicide cases and controls are given in Table I. Analysis Cases were identified from the cohort of 28,784 sawmill workers for each completed suicide and each attempted suicide. Using STTOCC (survival-time to case-control) on STATA 8.0, three controls were selected for each case matched on age. Controls were chosen randomly with replacement from the set at risk that comprised all the members of the cohort who worked in a study sawmill for at least one year. Thus, a control could be anyone at risk who also satisfied the above matching criteria. Statistical analyses were conducted using conditional logistic regression on STATA 8.0. First, we conducted univariate analyses for each of the two outcomes: attempted and completed suicide. The purpose of these univariate models was to identify associations between duration of employment, number of episodes of unemployment, job mobility, control (i.e. decision latitude), psychological demand, physical demand, social support, and noise, and attempted and completed suicide. Second, multivariate models were developed controlling for marital status, ethnicity, duration of employment at a study sawmill, and occupational status.

Results Results from the univariate models show no association between marital status, ethnicity, job mobility,

Downloaded from sjp.sagepub.com by RAVI BABU BUNGA on October 29, 2011

268

A. Ostry et al.

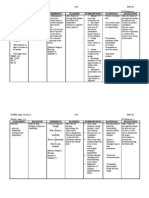

Table I. Sociodemographic and occupational characteristics of cases and controls. Completed suicide Case n5162 Control n5486 Attempted suicide Case n5127 Control n5381

Marital status (%) Unmarried 36 46.3 Married 64 53.7 Unstated 0 0 Ethnicity (%) Caucasian 92 93.9 Sikh 5.7 5.5 Chinese/Other Asian 2.3 .6 Occupational status at time of event (%) Manager 5.3 1.2 Tradesman 23.6 22.7 Skilled 17.2 12.3 Unskilled 53.9 63.8 Average duration (years) of employment at a study sawmill (mean (SD)) 6.9 (6.98) 5.5 (5.8)

34.1 55.9 10 93.1 6.2 .7 4.4 21.3 17.8 56.5 7.5 (7.4)

34.4 56.0 9.6 93.3 6.1 .6 2.2 17.2 21.1 59.5 6.5 (6.8)

duration of employment, type of occupation, physical demand, noise, and attempted suicide. However, duration of employment, job mobility, and type of occupation were significantly associated with completed suicide. In addition, control and psychological demand were significantly associated with both attempted and completed suicide, while social support was associated only with attempted suicide (Table II). Results from the multivariate analysis show that after controlling for marital status, ethnicity,

duration of employment at a study sawmill, job mobility, and occupational status, low psychological demand was associated with greater odds for completed suicide and low social support was associated with greater odds for attempted suicide (Table III). Discussion This study suggests that, after controlling for potential sociodemographic and occupational

Table II. Univariate results for attempted and completed suicides. (OR (95%CI) (p-value))* Completed suicide Marital statusa OR (95%CI) (p-value) 0.97 (0.90, 1.06) (0.54) Ethnicityb Sikh Chinese Occupational status at time of eventc Tradesman Skilled Unskilled Average duration (years) of employment at sawmill Job mobility while employed Control Psychological demand Physical demand Social support Noise 0.64 0.95 0.76 1.04 0.92 0.79 (0.46,0.91) (0.90,1.00) (0.67,0.85) (0.73,1.50) (0.75,1.13) (0.56,1.11) (0.01) (0.04) (0.00) (0.80) (0.42) (0.18) 1.04 0.96 0.90 0.89 0.84 0.92 (0.77,1.42) (0.92,0.99) (0.83,0.97) (0.66,1.21) (0.72,0.99) (0.67,1.26) (0.78) (0.03) (0.01) (0.46) (0.04) (0.61) 0.97 (0.45,2.08) (0.96) 0.27 (0.03,2.11) (0.21) 4.79 (1.04,21.99) (0.04) 3.62 (0.76,17.24) (0.11) 6.17 (1.87,27.77) (0.02) 0.95 (0.92,0.99) (0.01) 0.98 (0.91, 1.06) (0.63) 1.27 (0.68,2.36) (0.46) 0.43 (0.05,3.48) (0.43) 0.76 (0.50,1.16) (0.20) 1.14 (0.77,1.69) (0.51) 1.21 (0.87,1.68) (0.25) 0.98 (0.95,1.00) (0.07) Attempted suicide

a Married5referent; bCaucasian5referent; cmanager5referent. *p value bolded if statistically significant (v0.05).

Downloaded from sjp.sagepub.com by RAVI BABU BUNGA on October 29, 2011

Psychosocial work conditions and suicide among sawmill workers

269

Table III. Multivariate results for attempted and completed suicides after controlling for sociodemographic and non-psychosocial work condition variables. Completed suicide Marital status Sikh Chinese Tradesman Skilled Unskilled Duration of employment Psychological demand Social support 0.96 1.29 0.24 3.39 2.42 3.24 0.98 0.78 (0.89,1.05) (0.38) (0.58,2.87) (0.53) (0.03,1.93) (0.18) (0.73,15.83) (0.12) (0.50,11.68) (0.27) (0.70,15.04) (0.13) (0.95,1.02) (0.29) (0.69,0.89) (0.00) Attempted suicide 0.99 (0.92,1.06) (0.75) 1.08 (0.53,2.23) (0.83) 0.79 (0.09,7.35) (0.84)

1.00 (0.99,1.00) (0.07) 0.98 (0.87,1.10) (0.87) 0.73 (0.54,0.98) (0.04)

confounders, low psychological demand was associated with increased odds for completed suicide among this cohort of sawmill workers. As well, low social support was associated with increased odds for attempted suicide. The fact that two different aspects of the psychosocial working conditions are associated with attempted and completed suicide suggests that there may be different risk factors associated with attempted suicide and completed suicide. The results of the present study help understand what specific working conditions may be associated with suicidal behaviors and contribute to the development of a theoretical framework explaining attempted and completed suicide. For example, we found that the lack of social support at the work place was a risk factor for attempted suicide among male sawmill workers. However, lack of social support was not found to be a risk factor for completed suicide, which was instead associated with low levels of psychological demand. The members of this sawmill worker cohort had to be employed for at least one year so that the most transient sawmill workers were excluded from the study. Nonetheless, some cohort members were employed consistently whereas others experienced periodic layoff and re-hiring at the study mills. Univariate analysis from this study indicated that those workers who experienced more periodic layoffs (i.e. those who were less well attached to the study sawmill workforce) had a greater risk of completed suicide but not of attempted suicide. This result is consistent with the literature, where unemployment is consistently found as a risk factor for suicide. It is possible that periodic layoffs (i.e. short but repeated periods of unemployment) may contribute significantly to the cumulative burden among vulnerable individuals, which, in conjunction with low psychological demand, could lead them to extreme suicidal behaviors such as completed suicide.

The findings of this study and the proposed explanation are in apparent contrast with the emerging literature on karoshi, which has raised the possibility that high psychological demands, resulting from lean production methods, may be associated with death from overwork, including suicides, in Japan. However, it can also be hypothesized that both low psychological demand and high psychological demand at the workplace are risk factors for completed suicide. This hypothesis is supported by the study that found a U-shaped association between severe work stress and minimal work stress and suicide among US nurses [28]. The strengths of this investigation include the rigorous longitudinal study design, and the use of objective measures of both the exposure and outcome variables. On the other hand, the results cannot be generalized to a female population, or a population with different demographic and occupational characteristics. An additional limitation arises because of the potential for exposure misclassification from the retrospective and objectively assessed exposures. This latter limitation would probably have attenuated any association between exposure and outcomes so that the results obtained in this investigation may in fact be an under-estimation of the relationship between psychosocial work exposures and these suicide outcomes. As well, the correlation between indirectly assessed and self-reported working conditions is much better for blue-collar workers than for white-collar workers, which may reduce the potential to apply these indirect assessment methods to white-collar workforces. In summary, the results from the present study indicate that psychosocial working conditions may be important risk factors contributing to suicidal behaviors. Results from the present study also indicate that different psychosocial work conditions may be associated with attempted and completed suicide.

Downloaded from sjp.sagepub.com by RAVI BABU BUNGA on October 29, 2011

270

A. Ostry et al.

follow-up study of a cross-sectional sample of 37,789 people. Public Health 1997;111:415. Qin P, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB. Suicide risk in relation to socioeconomic, demographic, psychiatric, and familial factors: A national register-based study of all suicides in Denmark, 19811997. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160: 76572. Voss M, Nylen L, Floderus B, Diderichsen F, Terry PD. Unemployment and early cause-specific mortality: A study based on the Swedish twin registry. Am J Public Health 2004;94:215561. Gunnell D, Lewis G. Studying suicide from the life course perspective: Implications for prevention. Br J Psychiatry 2005;187:2068. Mortensen PB, Agerbo E, Erikson T, Qin P, WestergaardNielsen N. Psychiatric illness and risk factors for suicide in Denmark. Lancet 2000;355:912. Gunnell D, Lopatatzidis A, Dorling D, Wehner H, Southall H, Frankel S. Suicide and unemployment in young people: Analysis of trends in England and Wales, 1921 1995. Br J Psychiatry 1999;175:26370. Boxer PA, Burnett C, Swanson N. Suicide and occupation: A review of the literature. J Occup Environmental Med 1995;37:44252. Hilliardlysen J, Riemer JW. Occupational Stress and Suicide Among Dentists. Deviant Behavior 1988;9(4): 333346. Mccafferty FL, Mccafferty E, Mccafferty MA. Stress and Suicide in police officers: Paradigm of occupational stress. Southern Med J 1992;85:23343. Hawton K, Malmberg A, Simkin S. Suicide in doctors: A psychological autopsy study. J Psychosom Res 2004;57:14. Schmidtke A, Fricke S, Lester D. Suicide among German federal and state police officers. Psychol Rep 1999;84:15766. Feskanich D, Hastrup JL, Marshall JR, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, et al. Stress and suicide in the Nurses Health Study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2002;56:958. Beck AT, Brown G, Berchik RJ, et al. Relationship between hopelessness and ultimate suicide: A replication with psychiatric outpatients. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147:1905. Beck AT, Steer RA, Kovacs M, et al. Hopelessness and eventual suicide: A 10-year prospective study of patients hospitalized with suicidal ideation. Am J Psychiatry 1985;142:55963. Fawcett J, Scheftner W, Clark D, et al. Clinical predictors of suicide in patients with major affective disorders: A controlled prospective study. Am J Psychiatry 1987;144:3540. Hertzman C, Teschke K, Ostry A, Hershler R, DimichWard H, Kelly S, et al. Mortality and cancer incidence among sawmill workers exposed to chlorophenate wood preservatives. Am J Public Health 1997;87:719. Karasek R. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Admin Sci Q, 1979:285308. Ostry AS, Marion SA, Demers PA, Hershler R, Kelly S, Teschke K, et al. Measuring psychosocial job strain with the job content questionnaire using experienced job evaluators. Am J Ind Med 2001;39(4):397401. Ostry A, Marion SA, Green L, Demers PA, Hershler R, Kelly S, et al. Comparison of expert-rater methods for assessing psychosocial job strain. Scand J Work Environment Health 2001;27:16.

Acknowledgments The authors gratefully acknowledge the Canadian Population Health Initiative for their funding for this project. Acknowledgment is also made to the Canadian Institute of Health Research and Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research for Dr Ostrys salary support, and to the Canadian Institute of Health Research for Dr Maggis New Investigator Award.

[18]

[19]

[20]

[21]

References

[1] World Health Organization. Figures and facts about suicide. Geneva: WHO; 1999. [2] World Health Organization. Distribution of suicides rates (per 100,000) by gender and age, 2000. Geneva: WHO; 2005. [3] World Health Organization. Suicide prevention: Country reports and charts Canada. Geneva: WHO; 2005. [4] Platt S, Pavis S, Akram G. Changing labour market conditions and health: A systematic literature review (19931998). Dublin, Ireland: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions; 1999. [5] Shioiri T, Nishimura A, Akazawa K, Abe R, Nushida H, Ueno Y, et al. Incidence of note-leaving remains constant despite increasing suicide rates. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005;59:2268. [6] Lamar J. Suicides in Japan reach a record high. Br Med J 2000;321:528. [7] Nishiyama K, Johnson JV. Karoshi death from overwork: Occupational health consequences of Japanese production management. Int J Health Serv 1997;27:62541. [8] Amagasa T, Nakayama T, Takahashi Y. Karojisatsu in Japan: Characteristics of 22 cases of work-related suicide. J Occup Health 2005;47:15764. [9] Beautrais AL. Suicide in New Zealand II: A review of risk factors and prevention. N Z Med J 2003;(1175):U461. [10] Fekete S, Voros V, Osvath P. Gender differences in suicide attempters in Hungary: Retrospective epidemiological study. Croatian Med J, 2005:28893. [11] Hintikka J, Pesonen T, Saarinen P, Tanskanen A, Lehtonen J, Viinamaki H. Suicidal ideation in the Finnish general population: A 12-month follow-up study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2001;36:5904. [12] Platt S. Unemployment and suicidal behaviour: A review of the literature. Soc Sci Med 1984;19:93115. [13] Morton MJ. Prediction of repetition of parasuicide: With special reference to unemployment. Int J Soc Psychiatry 1993;39:8799. [14] Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. The effects of unemployment on psychiatric illness during young adulthood. Psychol Med 1997;27:37181. [15] Blakely T. The New Zealand Census-Mortality Study: Socioeconomic inequities and adult mortality 19911994. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2002. [16] Lewis G, Sloggett A. Suicide, deprivation, and unemployment:Record linkage study. Br Med J 1998;317:12836. [17] Johansson SE, Sundquist J. Unemployment is an important risk factor for suicide in contemporary Sweden: An 11-year [22]

[23]

[24]

[25]

[26] [27]

[28]

[29]

[30]

[31]

[32]

[33]

[34]

[35]

Downloaded from sjp.sagepub.com by RAVI BABU BUNGA on October 29, 2011

Psychosocial work conditions and suicide among sawmill workers Appendix: Thirteen-item questionnaire (Raters responded to the 13 statements with one of the following answers. Strongly disagree, disagree, agree, strongly agree.) (A) Items measuring control 1. The job required learning new things. 2. The job involved a lot of repetitive work. 3. The job required a high level of skill. 4. The job had a variety of tasks. 5. The worker had a lot to say about what happened on the job. 6. On this job, the worker had a lot of freedom to decide how to do the work. (B) Items measuring psychological demands 7. 8. 9. (C) 10. (D) 11. 12. (E) 13.

271

The job did not involve an excessive amount of work. The worker had enough time to get the job done. The job was free from conflicting demands. Item measuring physical demand The job required lots of physical effort. Items measuring co-worker social support The worker could leave this job to talk with co-workers. The worker could interact with co-workers while they worked. Item measuring noise The job was noisy.

Downloaded from sjp.sagepub.com by RAVI BABU BUNGA on October 29, 2011

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- ATLS Post TestDocument1 pageATLS Post Testanon_57896987836% (56)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Fracture PathophysiologyDocument1 pageFracture PathophysiologyIrene Joy Gomez100% (2)

- Nursing Care PlanDocument5 pagesNursing Care PlanAnju Luchmun100% (2)

- MeningitisDocument2 pagesMeningitisapi-491868042No ratings yet

- NCP (Icu)Document2 pagesNCP (Icu)jessie_nuñez_263% (8)

- Unit-Iii: Depth PsychologyDocument10 pagesUnit-Iii: Depth Psychologyravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Intro Philosophy July 2017Document24 pagesIntro Philosophy July 2017ravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Attempted Suicides in India: A Comprehensive LookDocument11 pagesAttempted Suicides in India: A Comprehensive Lookravibunga4489No ratings yet

- A Very Short Introduction To EpistemologyDocument10 pagesA Very Short Introduction To Epistemologyravibunga4489No ratings yet

- 144 Factors Associated With Underweight and Stunting Among Children in Rural Terai of Eastern NepalDocument9 pages144 Factors Associated With Underweight and Stunting Among Children in Rural Terai of Eastern Nepalravibunga4489No ratings yet

- New Notes On ThinkingDocument45 pagesNew Notes On Thinkingravibunga4489No ratings yet

- SpinozaDocument8 pagesSpinozaravibunga4489No ratings yet

- LeibnitzDocument8 pagesLeibnitzravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Unit-Iii: Depth PsychologyDocument10 pagesUnit-Iii: Depth Psychologyravibunga4489No ratings yet

- 807participation, Representation, and Democracy in Contemporary IndiaDocument20 pages807participation, Representation, and Democracy in Contemporary Indiaravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Motivations For and Satisfaction With Migration: An Analysis of Migrants To New Delhi, Dhaka, and Islamabad814Document26 pagesMotivations For and Satisfaction With Migration: An Analysis of Migrants To New Delhi, Dhaka, and Islamabad814ravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Transforming Desolation Into Consolation: The Meaning of Being in Situations of Ethical Difficulty in Intensive CareDocument17 pagesTransforming Desolation Into Consolation: The Meaning of Being in Situations of Ethical Difficulty in Intensive Careravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Unit-Iii: Depth PsychologyDocument10 pagesUnit-Iii: Depth Psychologyravibunga4489No ratings yet

- 869Document22 pages869ravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Visiting Nurses' Situated Ethics: Beyond Care Versus Justice'Document14 pagesVisiting Nurses' Situated Ethics: Beyond Care Versus Justice'ravibunga4489No ratings yet

- 89.full INDIADocument34 pages89.full INDIAravibunga4489No ratings yet

- 299Document20 pages299ravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Trends in Understanding and Addressing Domestic ViolenceDocument9 pagesTrends in Understanding and Addressing Domestic Violenceravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Culture and Domestic Violence: Transforming Knowledge DevelopmentDocument10 pagesCulture and Domestic Violence: Transforming Knowledge Developmentravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Night Terrors: Women's Experiences of (Not) Sleeping Where There Is Domestic ViolenceDocument14 pagesNight Terrors: Women's Experiences of (Not) Sleeping Where There Is Domestic Violenceravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Transforming Desolation Into Consolation: The Meaning of Being in Situations of Ethical Difficulty in Intensive CareDocument17 pagesTransforming Desolation Into Consolation: The Meaning of Being in Situations of Ethical Difficulty in Intensive Careravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Meeting Ethical Challenges in Acute Care Work As Narrated by Enrolled NursesDocument10 pagesMeeting Ethical Challenges in Acute Care Work As Narrated by Enrolled Nursesravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Ethical Dilemmas Experienced by Nurses in Providing Care For Critically Ill Patients in Intensive Care Units, Medan, IndonesiaDocument9 pagesEthical Dilemmas Experienced by Nurses in Providing Care For Critically Ill Patients in Intensive Care Units, Medan, Indonesiaravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Violence Against Women: Justice System ''Dowry Deaths'' in Andhra Pradesh, India: Response of The CriminalDocument25 pagesViolence Against Women: Justice System ''Dowry Deaths'' in Andhra Pradesh, India: Response of The Criminalravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Impact of Language Barrier On Acutecaremedical Professionals Is Dependent Upon RoleDocument4 pagesImpact of Language Barrier On Acutecaremedical Professionals Is Dependent Upon Roleravibunga4489No ratings yet

- A Qualitative Analysis of Ethical Problems Experienced by Physicians and Nurses in Intensive Care Units in TurkeyDocument15 pagesA Qualitative Analysis of Ethical Problems Experienced by Physicians and Nurses in Intensive Care Units in Turkeyravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Challenges in End-Of-Life Care in The ICUDocument15 pagesChallenges in End-Of-Life Care in The ICUravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Care of The Traumatized Older AdultDocument7 pagesCare of The Traumatized Older Adultravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Respecting The Wishes of Patients in Intensive Care UnitsDocument15 pagesRespecting The Wishes of Patients in Intensive Care Unitsravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Transforming Desolation Into Consolation: The Meaning of Being in Situations of Ethical Difficulty in Intensive CareDocument17 pagesTransforming Desolation Into Consolation: The Meaning of Being in Situations of Ethical Difficulty in Intensive Careravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Penyakit Respirasi Pada AnakDocument29 pagesPenyakit Respirasi Pada AnakyudhaNo ratings yet

- Shaggy Aorta 8Document1 pageShaggy Aorta 8Eghet SilviuNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Kesehatan MentalDocument6 pagesJurnal Kesehatan MentalRayhan Gymnastiar NasirNo ratings yet

- Hemorragic Crebrovascular Accident: A Case Presentation of A Patient WithDocument7 pagesHemorragic Crebrovascular Accident: A Case Presentation of A Patient Withgerald_ichigo402No ratings yet

- PUP Health Declaration Form ADocument1 pagePUP Health Declaration Form ARJ DAWATONNo ratings yet

- DDs of Red EyeDocument15 pagesDDs of Red EyeSakshiNo ratings yet

- WS7 Bachti Alisjahbana - Pendekatan Klinis Demam Akut PDFDocument47 pagesWS7 Bachti Alisjahbana - Pendekatan Klinis Demam Akut PDFWindy R. PutraNo ratings yet

- Failure To ThriveDocument5 pagesFailure To ThriveSana SiddiqNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis B in PregnancyDocument17 pagesHepatitis B in PregnancysnazzyNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Hiv in Call Center Agents in The Philippines: de La Cruz, Barraca, SantosDocument12 pagesPrevalence of Hiv in Call Center Agents in The Philippines: de La Cruz, Barraca, SantosKarly De La CruzNo ratings yet

- Health Resources Center: Kingsport ScheduleDocument2 pagesHealth Resources Center: Kingsport ScheduleJack MiguelNo ratings yet

- FDA Approves First Treatment For A Form of Batten Disease FDADocument4 pagesFDA Approves First Treatment For A Form of Batten Disease FDAAnonymous EAPbx6No ratings yet

- Circular No. 3 1Document5 pagesCircular No. 3 1spawnn NVX7No ratings yet

- Quotes On VaccinesDocument6 pagesQuotes On VaccinesKris BargerNo ratings yet

- Ophthalmology For The Equine Practitioner 2002-2002Document2 pagesOphthalmology For The Equine Practitioner 2002-2002Francisco JulianNo ratings yet

- Journal Ocular Surface Tumor DiagnosticDocument22 pagesJournal Ocular Surface Tumor DiagnosticMuammar EduNo ratings yet

- CA NursingDocument5 pagesCA NursingMary Angel Nicka LuayonNo ratings yet

- Trends of Measles in Nigeria A Systematic ReviewDocument7 pagesTrends of Measles in Nigeria A Systematic ReviewRizki Nandasari SulbahriNo ratings yet

- ZIMIND 17 04 2020 P - CompressedDocument44 pagesZIMIND 17 04 2020 P - CompressedKennedy DubeNo ratings yet

- Causes of Clubbing - Google SearchDocument1 pageCauses of Clubbing - Google SearchSheikh AnsaNo ratings yet

- BFM - 978 0 387 09834 0 - 1Document30 pagesBFM - 978 0 387 09834 0 - 1Priyanka MishraNo ratings yet

- Surgery PyqDocument17 pagesSurgery PyqPrateek SinghNo ratings yet

- DafpusDocument6 pagesDafpusAnonymous 46SyYMQkNo ratings yet

- Damage Control Fixation of Displaced Femoral.10Document6 pagesDamage Control Fixation of Displaced Femoral.10Hizkyas KassayeNo ratings yet

- Sent Via U.S. Mail and Via E-MailDocument9 pagesSent Via U.S. Mail and Via E-MailThe Salt Lake TribuneNo ratings yet