Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Inventory Control

Uploaded by

scribdacct123Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Inventory Control

Uploaded by

scribdacct123Copyright:

Available Formats

Most companies have more freedom than they imagine to organize their supply chains for maximum efficiency.

By rethinking inventory control in terms of who owns the inventory at any point, where it should be located, and who controls it, managers can develop supply chains that ensure much stronger alignment between their companies and their trading partners. Historically, inventory control was fairly monolithic. A company owning inventory kept it at its premises and controlled the inbound and outbound flows of the materials. The ownership, location, and control of the inventory resided at the same corporate entity. New and highly sophisticated information technologies have enabled the tracking and visibility of inventory across company boundaries so that a company can have its inventory located at another's premises and can control it remotely. Supply chain management concepts such as VMI, Continuous Replenishment Program (CRP), supplier hubs, and outsourcing to third-party logistics (3PL) service providers are now in wide use. The control of inventory - the issue of who triggers and determines the quantity of inventory to be replenished - can also be decoupled from inventory location and ownership. In the case of inventory consignment or a supplier hub, for example, it could be either the buyer or the supplier who controls the replenishment decisions. It is clear that there are many variations of the design of inventory control, each with advantages that fit the needs of a particular environment.

Full Text Most companies have more freedom than they imagine to organize their supply chains for maximum efficiency. By rethinking inventory control in terms of who owns the inventory at any point, where it should be located, and who controls it, managers can develop supply chains that ensure much stronger alignment between their companies and their trading partners. Historically, inventory control was fairly monolithic. A company owning inventory kept it at its premises and controlled the inbound and outbound flows of the materials. The ownership, location, and control of the inventory resided at the same corporate entity. But in recent decades, these three dimensions have been decoupled in a variety of contractual forms, thanks largely to advances in information technology (IT) and to the maturity of modern supply chain management (SCM) concepts and practices. The decoupling is

evident everywhere from the vendor-managed inventory (VMI) programs used by Procter & Gamble to the supplier hubs that feed many electronics and high-tech manufacturing facilities. The upshot is that today's supply chain managers face many alternative ways of designing and implementing an inventory control system. In practice, they now have more freedom than they might think for designing their supply chains-and thus more opportunity to improve supply chain efficiencies. New and highly sophisticated information technologies have enabled the tracking and visibility of inventory across company boundaries so that a company can have its inventory located at another's premises and can control it remotely. Supply chain management concepts such as VMI, Continuous Replenishment Program (CRP), supplier hubs, and outsourcing to third-party logistics (3PL) service providers are now in wide use. These practices involve collaborative efforts between supply partners, whereby decision rights can be delegated from one party to another, risks and costs can be shared, and accountability and performances can be jointly owned. This article deconstructs the design of an inventory control system into its three components: who owns the inventory; where it is located; and how replenishment is controlled. We call this deconstruction the Whose, Where, and How of inventory control design. Our goal for this article is to help supply chain managers see with fresh eyes what most of them are doing already-and give them the tools to proactively redesign their inventory control systems to better align their companies' interests with those of their suppliers and other supply chain stakeholders. In essence, we want to help them move from the arbitrary inventory control designs that they may have had imposed upon them by other supply chain parties, or that they perceived to be best practice at one time. By demonstrating that they have many more degrees of freedom to configure their inventory control designs, we hope to help them significantly enhance their supply chain operations. The "Whose" Question Consider a warehouse at a plant that keeps a stockpile of materials, components or subassemblies (we will refer to them as "materials") to support the execution of production plans, as well as against production fluctuations or schedule uncertainties. The ownership of

inventory at the warehouse constitutes the first design question. Traditionally, supply chains involved the buyer owning the inventory of materials, since it was the buyer who made the decision as to when and how much of the materials were to be procured from the supplier. The buyer controlled the inventory, was accountable for it, and owned it. Nowadays, of course, this is not always the case. Let us look at some of ways in which inventory ownership is dispersed. Inventory Consignment Inventory consignment is a common practice in the retail industry. Let's assume that the supplier owns the inventory at the warehouse or distribution center. Ownership changes when inventory is withdrawn from the warehouse or sold to customers-as in the retail sector. Consignment is not necessarily tied to who triggers the replenishment of inventory at the warehouse, as either the buyer or the supplier can control the replenishment decisions. Hence, the ownership and the location of the inventory are decoupled in consignment. When supply chain partners collaborate on VMI and CRP arrangements-such as those between Wal-Mart and Procter & Gamble-they have to decide whether consignment is to be part of the agreement. When VMI is involved, we call it "VMI with consignment." Recently, scan-based trading (SBT) has emerged as a new form of consignment in retail; it effectively replicates the retail check-out transaction, where ownership changes hands at the point of sale, at the point at which suppliers transfer goods to the retailer. The supplier is paid at that point. (SBT is in use in other industries too-high-tech, for instance. When materials cross from the supplier hub into Nokia's plants, they are scanned and the payment cycle begins. Sony uses the same practice with its suppliers.) First tested in 2000 by the Grocery Manufacturers Association, SBT quickly showed quantifiable benefits. Sara Lee, as a supplier, found a 60 percent reduction in invoicing errors after it had adopted the technique, while Schnuck Markets, a retailer, found corresponding reductions of 70 percent. Besides helping to reduce stock-outs, the supplier's improved visibility of end demand helps to reduce the common bullwhip effect-the distortion of order demands by the buyer that results when the buyer's order variability is much greater than its consumption variability. The bullwhip effect distorts demand information, and the amplification of demand variability makes it difficult for the supplier to manage its production and inventory effectively.

Pre-Positioning or Reverse Consignment Another example of ownership-location disparity involves the prepositioning of raw materials so that suppliers can respond to highly volatile demands. This is a common practice in the fashion industry. Having the right fabrics at the right time is critical for responsiveness, but fabric suppliers are reluctant to take the risk of holding extra inventories. To resolve the dilemma, the apparel manufacturer can purchase extra inventory and pre-position it at the supplier's facilities. Note that pre-positioning can also be in the form of capacity reservation (such as for dyeing and printing operations). This is what Li and Fung has used successfully to shorten lead times of fashion products to its brand-name customers. Similarly, in the high-tech sector, disk-drive manufacturer Seagate maintains both a die-bank (processed wafers awaiting assembly into semiconductor devices) and reserved capacity at its chip supplier's fabrication plant, so it can obtain the chips it needs at short notice. Indeed, this is becoming an increasingly popular practice for fab-less semiconductor manufacturing. One may call pre-positioning "reverse consignment," since the product is owned by the buyer and located at the supplier's site; in effect, it is the mirror image of consignment. In the case of pre-positioning of inventory, the separation between ownership and location arises in order to first position the materials at the "scene of action" (for example, the retail space or assembly site), and then to determine its ownership by considering other factors such as incentive alignment and risk allocation. Third-Party Inventory Owner Bargaining power is another important factor that determines who should own the inventory. During the Internet boom, large original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) such as Cisco had to make extensive commitments to some suppliers to purchase certain quantities of scarce parts months in advance. When the Internet bubble burst, it was the OEMs that had to write off many of those commitments on their books. This happened because the parts makers, regardless of their size, held the bargaining power. In general, large OEMs enjoy more bargaining power and can usually dictate the terms of the shift of inventory ownership---especially if the supplier is a small or medium-sized enterprise (SME). But this can lead to a problem of "inefficient risk allocation." An SME supplier may

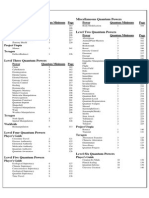

have to incur higher financial costs to finance inventory at the buyer's warehouse, which of course is not healthy for the overall supply chain. A study of supply chain practices by software provider WorldChain, presented at Stanford's Global Supply Chain Management Forum conference in 2004, found that the popularity of having suppliers owning inventory caused them to shoulder a heavily skewed share of the inventory burden (see Exhibit 1). To ease this problem, Silicon Valley Bank launched an inventory financing service some years ago whereby the bank bought the inventory from the supplier. The transaction only occurred in the information sense-the title changed but no physical movement of the inventory was required. The bank's costs of financing the inventory were much lower, of course. The supplier was paid as soon as the bank took title to the inventory; buyers would buy inventory from the bank as needed. Although Silicon Valley Bank has withdrawn this service due to legal constraints that restrict banks from owning inventory, other financial institutions and logistics providers, such as GE Capital and DHL, have jumped in, and several software providers have developed useful trade financing tools. Today, there is a flourishing business in improving efficiencies in the financial supply chain. (See "Gaining an Edge in Supply Chain Financing," Supply Chain Management Review , Nov-Dec 2007.) Exhibit 2 shows a typical trade financing mechanism. The Good and Bad of Inventory Ownership Inventory ownership is not "all cost with no gain." When the supplier owns the inventory, one key benefit to the supplier is direct visibility of the inventory. In the case of a supplier hub, the buyer may withdraw inventory from the hub daily-or in some cases, several times a day. The information about the withdrawal is also available to the supplier. Since most buyers with a supplier hub do not have to store much inventory on the production line, the withdrawals represent usage at the production line. Hence, direct ownership of inventory translates to direct access to information about the buyer's usage patterns, which helps avoid the bullwhip effect. Another reason for wanting to own inventory is somewhat rare, but it can happen in retail. Seven Eleven Japan, that nation's largest convenience store chain, enjoys 55 inventory turns a year, meaning that an average item stays at the store for only a

week. If suppliers are paid on a five-week term, the chain can keep the cash for four weeks before paying its suppliers. The "Where" Question The "where" question refers to determining the location of the inventory, which can be the buyer's site, the supplier's site, or in some cases, a third party's site. Traditionally, the supplier keeps his inventory at his premises, and the buyer keeps hers at her premises. In the case of a "supplier hub," however, the two sets of inventories are pooled at a single location. Buyer's On-Site Inventory In this arrangement, most supplier parts are usually stocked at the premises of the buyer. The advantages are many. For a start, replenishment lead times to the production lines are short since inventories are under the same roof. Also, on-premise inventory is clearly at the disposal of the buyer so there is little risk that it might be diverted or used elsewhere. The latter is especially critical when the component is in short supply. At the same time, the visibility of on-premise inventory makes inventory accounting and auditing straightforward. On-Site Supplier Hubs A supplier hub (also called VMI hub, inbound hub or vendor hub) is a parts warehouse at or near a buyer's premises. Its common characteristics include the following: the arrangement is for multiple suppliers serving the buyer; the hub materials are owned by the supplier; it is operated by a 3PL provider; and it is supported by an inter-organizational information system to share information across partners. The supplier hub was spearheaded by companies such as Dell and Apple. The model is widely used in the electronics, automotive and retail industries, at companies such as Apple, Dell, Fiat, HewlettPackard, Nokia, Sam's Club, Cisco, Samsung Electronics, Flextronics, Solectron, and Volkswagen. The hub can be located at the buyer's site (on-site supplier hubs), or at a neutral party's site (off-site supplier hubs). Exhibit 3 shows how a typical supplier hub works. For the buyer, supplier hubs offer many advantages. For a start, there is just-in-time access to additional inventory without an associated financial burden. The buyer can dynamically adjust production schedules as market circumstances dictate. Also, supplier hubs enable a company to focus on its core competencies by

outsourcing inbound logistics to 3PL and suppliers. In addition, both parties can use the inter-organizational information system to track and trace the inventory in the pipeline (that is, the vendor, ocean shipping, customs clearing, long-haul trucking, and the supplier hub). Often, a 3PL consolidates freight across multiple suppliers in the same region (by converting less-than-truckloads into full truckloads) and lowers the freight cost for suppliers. The 3PL contributes to the supplier hub by planning and executing all logistics functions in the pipeline, providing the inter-organizational information system, selling value-added services such as customs clearance and freight consolidation, and operating the physical facilities at the hub itself. To the supplier, the key downside of supplier hubs is the extra inventory burden. In addition, if a supplier has to stock inventory at multiple supplier hubs (one for each major customer), it may lose the benefits of inventory pooling. That's what happened to Quantum prior to its merger with Maxtor. The disk-drive maker, now part of Seagate, used to carry inventories at a dozen sites, all under its own control. But with the proliferation of supplier hubs at its customers, Quantum had to manage more than 500 inventory sites, which entailed large management costs. Those costs are offset to some extent by the benefits of being able to secure an outpost of continuous sales at the buyer's plant, and perhaps a foothold into a similar relationship in the next generation of products. That is why some supplier companies volunteer to operate such outposts at the buyers' premises. For example, Owens & Minor, a distributor of medical products to hospitals, carries inventories of medical products at its key client hospitals, so doctors and nurses can readily pull the inventory and pay later. Off-Site Supplier Hubs Some supplier hubs are located at "neutral" premises; they are not owned or directly controlled by the buyer, and are usually not far from the plant-30 minutes away, say. There can be a range of advantages for such an arrangement: Having the supplier hub located outside the buyer's premises is one way to clearly signify that the inventory there is owned by the supplier. Unlike inventory consignment where the buyer must be responsible for insurance, accounting, storage and even maintenance of the inventory, supplier-owned inventory at premises outside of the

buyer's facilities shifts the responsibility and liability completely onto the supplier. In some cases, the supplier hub may be used to serve more than one buyer. This enables the supplier to partially recuperate the risk-pooling benefits of its inventory and space requirements. Such a "divert" option would necessitate that the hub is located outside of a single buyer. Some supplier hubs are declared by the buyers to be "bonded warehouses." This means that, if the parts come from overseas, the buyer does not have to immediately pay customs and duties on the inventory at the hub. Instead, customs and duties are levied only when inventory is moved to the production facility. Traditionally, if inventory is located at the production facility, customs and duties have to be paid as soon as the parts arrive at the port of entry. Supplier hubs can be located a few miles away from the production facilities, giving both parties a lot of flexibility. The hub can be located where property costs are lower, or near the transportation hubs of the 3PLs that transport the goods from the suppliers to the hub. It also could allow more space for the hub to sequence multiple parts in sync with the buyer's production schedule, obviating the need to mix and sequence the parts at the production line. This is a common practice among automobile manufacturers. Physical premises outside the buyer's production location are required in order to pursue the inventory financing option described in the previous section. The "How" Question The control of inventory-the issue of who triggers and determines the quantity of inventory to be replenished-can also be decoupled from inventory location and ownership. In the case of inventory consignment or a supplier hub, for example, it could be either the buyer or the supplier who controls the replenishment decisions. Inventory Consignment for Incentive Alignment At first, it may appear natural to conclude that whoever made the replenishment decisions should be accountable for their consequences and therefore should own the material inventory. However, inventory consignment exists whereby the supplier owns the material inventory even if the buyer was the replenishment decision-maker. This arrangement often stems from attempts to align the incentives of a supply chain. It is a form of inventory cost subsidy because the

buyer does not have to bear the inventory's full capital cost. The result is that the buyer becomes more aggressive in procuring materials. We have seen that a buyer may under-stock (or under-purchase) inventory from the supplier if it has to bear the full cost of inventory, which sub-optimizes the supply chain. Inventory consignment is one form of incentive alignment that can be applied to improve the overall supply chain performance. A variant of cost subsidy is appropriately generous return policy. In this case, too, the buyer has almost full control over the timing and size of replenishment, but the right to return unsold or unwanted items without penalty serves as a proxy for consignment, thereby achieving inventory risk-sharing and aligning incentives. Benefits of VMI VMI offers another example of the ownership-control disparity. VMI movement stipulates that the supplier is in charge of the replenishment decisions. A key benefit of VMI, whether consigned or not, is avoidance of the bullwhip effect. Also, under VMI, the supplier does not have to be reactive to every order a buyer places, and as a result may have more flexibility to schedule production runs or replenishments to optimize its supply chain. The supplier may also determine the best delivery schedule in order to optimize its transportation costs. For example, if two buyers place orders at different but close enough times, the supplier could use the same truck to build a full truckload. Furthermore, if VMI is conducted with inventory consignment, the truck may pick up surplus stock at one retailer and trans-ship it to another. Thus, the supplier in consignment would have more degrees of freedom to rebalance retailers' inventories in a centralized manner. Mixed Control: From VMI to JMI But what about the supplier that makes replenishment decisions while the buyer owns the inventory? There are many instances of "VMI without consignment," in which the supplier controls the replenishment decision but the buyer owns the inventory. Saturn is one well-known case. The automaker controls replenishments of spare parts to Saturn dealers. But once the parts inventory arrives, the dealer owns it. Saturn does allow the "retailers" (as it calls its dealers) to adjust the replenishment decisions it makes, which is why the automaker calls it JMI (jointly managed inventory). But the dealers lack full decision rights.

The main purpose of such an arrangement seems to be to emulate the inventory-service performance of multi-echelon inventory control. To align its incentives with those of its dealers, Saturn created something called "obsolescence protection." Even though the dealers own the parts inventory, Saturn is willing to take it back if the parts do not sell in nine months. In that sense, the arrangement amounts to partial consignment by Saturn. The scheme also gives Saturn the ability to trans-ship parts from one dealer to another to address any stock-outs. Control Based on Market Expertise Market expertise is another factor that determines who should control the inventory. Dreyer's manages a designated shelf space of the icecream sections at retailers using its superior knowledge of market trends and its ever-changing portfolio of flavors. Dreyer's is granted full control over the shelf space, determining the mix and location of different SKUs in it. Using SBT, the company gets paid when the items are sold at the retailers. In that way, the ice-cream producer can try new flavors in different regions, learn about demand behaviors, and apply what it learns to other regions and other retailers. Similarly, Procter & Gamble usually works under "VMI without consignment" with its large retailers for most of its products such as soap, shampoo, toothpaste, and detergents. But with newly developed health and beauty products, P&G pursues "VMI with consignment." Since the company has superior information about the potential performance of its new products, it will more readily take the risk in return for higher degrees of freedom in its experimentation. Note here that control, decoupled from inventory ownership or location, is used as a design parameter to optimize the supply chain. Incentive Problems Under VMI A natural concern arises when inventory control and ownership are separated: If the supplier controls the inventory to be owned by the buyer, how can the buyer check and balance the supplier's incentives to exploit them for its own interests? It is a valid concern: recall the case of Cisco's inventory write-off in 2001. The communications equipment maker had outsourced most of its production to EMS (electronic manufacturing services) companies. Dealing with explosive growth, Cisco chose to forward-buy and preposition scarce components at the EMS sites. Cisco even allowed the EMS manufacturers to purchase and hold parts for Cisco. Ownership of the parts was truly separate from their location and control.

However, the EMS firms began to aggressively acquire parts, since by doing so, they could get more orders from Cisco than their competitors could. Total orders of scarce parts soon became two and three times actual demand. When the Internet bubble burst, the owner of the inventory-Cisco-had to underwrite the bulk of the losses and write off obsolete excess inventories worth $2.25 billion. Learning from that experience, Cisco has expanded the scope and depth of its "e-Hub" internal information system so it can see, in real time, the status of the inventory, commitments and capacity at thousands of suppliers, three supplier tiers deep. Cisco can now manage the "book" of orders so the total commitment stays within reasonable bounds. Note that "VMI with consignment" can also misalign supplier-buyer incentives in multi-vendor environments. Consider a retailer that resells competing products from two suppliers, A and B. If A operates on "VMI with consignment" and B on "VMI without consignment," the retailer would make every effort-for example, with better store displays-to sell B's product first since the retailer owns it and incurs inventory cost for any unsold units. Design Alternatives There are many inventory control designs that are based on the "whose," "where," and "how" dimensions. Exhibit 4 summarizes ten alternatives along with a handful of examples. We will briefly describe each of them below. Designs 1 and 6 are standard models of inventory control and need no explanation. Designs 3 and 5 include variations of VMI. The buyer lets the supplier control the inventories at the former's site, either paying upon delivery-which is what Procter & Gamble does-or upon withdrawals or usage, as Nokia does, or upon sales to end consumers, as is the case with ice-cream supplier Dreyer's. Design 2 represents the standard consignment model where the buyer controls the inventory on its site and pays the supplier upon inventory withdrawal. In a supplier hub, it is often unclear who really controls the inventory. Even if the supplier appears to have control, it must count on the buyer's demand forecasts to set the proper stock level. Here, the buyer may have significant power to induce the supplier to carry her desired level of inventory. That is the case with Dell's supplier hub (Design 4), where rigid min-max levels of inventory are given to

suppliers. Drop-shipping in e-commerce is another example of Design 4. In Design 7, inventory is pre-positioned as intermediate work in process (such as the die bank in semiconductor manufacturing) at the supplier's site by the buyer, and the withdrawal of the inventory (often in the form of customization or final assembly) is also controlled by the buyer. Design 8 is one in which the buyer forward-buys but lets the supplier have final control of actual inventory to be purchased. This is often done in times of scarcity or potential shortage. For example, Starbucks forward-buys high-quality coffee beans from a select group of farms well in advance of the harvest time, even though the final control of harvests rests with the supplier. Design 9 is actually a variant of Design 5. But in this case, a thirdparty site, often belonging to a 3PL, is used to stock inventory instead of the buyer's site. Design 10 is a variant of the supplier hub version of Design 6, where ownership of inventory is transferred from the supplier to a third party such as a financial intermediary. Better Design, More Efficiencies It is clear that there are many variations of the design of inventory control, each with advantages that fit the needs of a particular environment. In this article, we have highlighted the decoupling of the ownership, location, and control of inventory, and touched on some ways in which decoupling, planned for and managed appropriately, can improve supply chain efficiencies. A quick survey of many industry sectors reveals that most companies today are, de facto, adopting elements of the decoupling approach. However, it is our observation that supply chain managers at those companies have not been able to analyze and deconstruct their practices and so are unaware of how to use the decoupling approach to its full potential. Facing increased pressure to contain costs, those managers have to find ways to squeeze more efficiencies out of their supply chains. They can do so by understanding the implications of their inventory control designs and constructing designs that are optimal for their companies and for their partners. We hope that this article now gives them the framework they need to do so.

You might also like

- Reebok NFL Case StudyDocument4 pagesReebok NFL Case StudyKomal GuptaNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain ManagementDocument49 pagesSupply Chain Managementmanoj rakesh85% (46)

- Beheshti2020 PDFDocument20 pagesBeheshti2020 PDFVINITHANo ratings yet

- WEEK 1 Reading MaterialsDocument13 pagesWEEK 1 Reading MaterialsNitishSarafNo ratings yet

- Reshaping Retail: Why Technology is Transforming the Industry and How to Win in the New Consumer Driven WorldFrom EverandReshaping Retail: Why Technology is Transforming the Industry and How to Win in the New Consumer Driven WorldNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument114 pagesPDFMusa A. Hassan100% (1)

- Retail Supply Chain ManagementDocument9 pagesRetail Supply Chain ManagementShivatiNo ratings yet

- History of Push and Pull Inventory PhillosophiesDocument6 pagesHistory of Push and Pull Inventory PhillosophiesRishaana SaranganNo ratings yet

- Agile Supply Chain: Assignment 1Document13 pagesAgile Supply Chain: Assignment 1aritri_kumarNo ratings yet

- Continuous Replenishment and VendorDocument5 pagesContinuous Replenishment and VendorZameer AhmedNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Synchronization: White PaperDocument4 pagesSupply Chain Synchronization: White PaperBrooke TillmanNo ratings yet

- Agile Supply ChainDocument8 pagesAgile Supply ChainOlumoyin Tolulope100% (1)

- Chapter Seven: The Synchronous Supply ChainDocument11 pagesChapter Seven: The Synchronous Supply ChainMohaimin Azmain NuhelNo ratings yet

- SCM 301Document10 pagesSCM 301Manda simzNo ratings yet

- Consumption Driven ReplenishmentDocument4 pagesConsumption Driven Replenishmentsappz3545448No ratings yet

- Vendor Managed Inventory Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesVendor Managed Inventory Literature Reviewc5p9zbep100% (1)

- Capitulo 5Document5 pagesCapitulo 5VianethNo ratings yet

- Vendor Managed InventoryDocument2 pagesVendor Managed InventoryAdnan NawabNo ratings yet

- Inventory ManagementDocument5 pagesInventory Managementmickaellacson5No ratings yet

- Supply NetworkingDocument3 pagesSupply NetworkingAizel ParpadoNo ratings yet

- 17-Supply Chain StrategyDocument37 pages17-Supply Chain Strategymanali VaidyaNo ratings yet

- Coronavirus's Impact On Supply Chain - McKinseyDocument10 pagesCoronavirus's Impact On Supply Chain - McKinseyShiKhei ChanNo ratings yet

- LeslyDocument3 pagesLeslymickaellacson5No ratings yet

- Inventory and Logistics - IntroDocument5 pagesInventory and Logistics - IntroAshi gargNo ratings yet

- Clothes MBA Mini ProjectDocument31 pagesClothes MBA Mini Projectavadhesh kumarNo ratings yet

- Vendor Managed Inventory Research PaperDocument4 pagesVendor Managed Inventory Research Papersoezsevkg100% (1)

- DPS 202 AssingmentDocument13 pagesDPS 202 AssingmentsharonNo ratings yet

- What Is Push and Pull Strategy in Supply Chain ManagementDocument4 pagesWhat Is Push and Pull Strategy in Supply Chain Managementnivedita vermaNo ratings yet

- Inventory Management ProjectDocument89 pagesInventory Management ProjectVinay Singh100% (1)

- Risk PoolingDocument3 pagesRisk PoolingÄyušheë TŸagïNo ratings yet

- Inventory Management-Nishi KantrDocument53 pagesInventory Management-Nishi KantrNishi KantNo ratings yet

- Warehousing TodayDocument3 pagesWarehousing Todaylucia.torremochaNo ratings yet

- CPFR Whitepaper Spring 2008-VICSDocument25 pagesCPFR Whitepaper Spring 2008-VICSakashkrsnaNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3952925Document49 pagesSSRN Id3952925Mindaugas ZickusNo ratings yet

- Name: ID: COURSE: Operations Management Course Teacher: Dr. Di LingDocument16 pagesName: ID: COURSE: Operations Management Course Teacher: Dr. Di LingTawsif Shafayet AliNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain ManagementDocument29 pagesSupply Chain ManagementShamNo ratings yet

- SCLM NotesDocument43 pagesSCLM NotesJyoti SinghNo ratings yet

- Bull-Whip Mitigation StrategieDocument3 pagesBull-Whip Mitigation StrategieHariSharanPanjwaniNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 Operations and Supply Chain ManagemetDocument6 pagesChapter 10 Operations and Supply Chain ManagemetArturo QuiñonesNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 NoteDocument9 pagesUnit 3 NoteRavi GuptaNo ratings yet

- IT Enabled Supply Chain Management.Document46 pagesIT Enabled Supply Chain Management.anampatelNo ratings yet

- FinalAssignmentDocument5 pagesFinalAssignmentAB BANo ratings yet

- Topic 8. Warehouses and Distribution CentersDocument7 pagesTopic 8. Warehouses and Distribution CentersAbigail SalasNo ratings yet

- Apa FormatDocument7 pagesApa FormatAimira AimagambetovaNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain ManagementDocument27 pagesSupply Chain ManagementParth Kapoor100% (1)

- Supply Chain MGMT Project1Document40 pagesSupply Chain MGMT Project1arvind_vandanaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Supply Chain Management StrategyDocument13 pagesChapter 3 Supply Chain Management StrategyAnup DasNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain ManagementDocument9 pagesSupply Chain ManagementRupesh SinghNo ratings yet

- Supply ChainDocument8 pagesSupply ChainŠ Òű VïķNo ratings yet

- Quick Response LogisticsDocument18 pagesQuick Response LogisticsPrasad Chandran100% (7)

- Chapter 3 Discussion Questions: Chapter 3: Supply Chain Drivers and MetricsDocument2 pagesChapter 3 Discussion Questions: Chapter 3: Supply Chain Drivers and MetricsShahrukh khanNo ratings yet

- Retail Analytics Unit 3Document19 pagesRetail Analytics Unit 3Adarsh DashNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain MnagementDocument5 pagesSupply Chain MnagementDanish AhsanNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain ManagementDocument6 pagesSupply Chain ManagementHarshith Kumar H RNo ratings yet

- Thi S Is Also Known As A "Pull System," and It Entails The FollowingDocument4 pagesThi S Is Also Known As A "Pull System," and It Entails The FollowingMinh Anh MinhNo ratings yet

- Retailer Supplier PartnershipDocument12 pagesRetailer Supplier PartnershipSanjeev Bishnoi100% (1)

- Fundamental of Logistics and Supply Chain ManagementDocument8 pagesFundamental of Logistics and Supply Chain ManagementAparajith ShankarNo ratings yet

- 9 Reglas B Sicas de Una Cadena de Suministro ExitosDocument10 pages9 Reglas B Sicas de Una Cadena de Suministro ExitosbvasconezNo ratings yet

- Enterprise Supply Chain Management: Integrating Best in Class ProcessesFrom EverandEnterprise Supply Chain Management: Integrating Best in Class ProcessesNo ratings yet

- Brine Shrimp Toxicology LabDocument1 pageBrine Shrimp Toxicology Labscribdacct1230% (1)

- L TEX and The Gnuplot Plotting ProgramDocument10 pagesL TEX and The Gnuplot Plotting Programscribdacct123No ratings yet

- N+ GuideDocument15 pagesN+ Guidescribdacct123No ratings yet

- BuyingDocument1 pageBuyingscribdacct123No ratings yet

- United Nations Convention On Jurisdictional Immunities of States and Their PropertyDocument12 pagesUnited Nations Convention On Jurisdictional Immunities of States and Their PropertyEndah Rastri MustikaningrumNo ratings yet

- PurchaseDocument1 pagePurchasescribdacct123No ratings yet

- dc01 Show - PpsDocument49 pagesdc01 Show - Ppsscribdacct123No ratings yet

- Master Powers ListDocument1 pageMaster Powers Listscribdacct123100% (2)

- Tipv5 PDFDocument11 pagesTipv5 PDFscribdacct123No ratings yet

- VoluntaryistDocument499 pagesVoluntaryistuccmeNo ratings yet

- Svyatoslav BabchanikDocument2 pagesSvyatoslav Babchanikscribdacct123No ratings yet

- IEEE Conformance PHY BookDocument14 pagesIEEE Conformance PHY Bookscribdacct123No ratings yet

- Sigil 156 Is in The HouseDocument1 pageSigil 156 Is in The Housescribdacct123No ratings yet

- Financial Disclosures Checklist: General InstructionsDocument35 pagesFinancial Disclosures Checklist: General InstructionsPaulineBiroselNo ratings yet

- Operations Management: Chapter 2 - Operations Strategy in A Global EnvironmentDocument35 pagesOperations Management: Chapter 2 - Operations Strategy in A Global EnvironmentMichael Tuazon LabaoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 Aggregate PlanningDocument40 pagesChapter 5 Aggregate PlanningMarvin kakindaNo ratings yet

- Caso 2 - Gerencia de Operaciones 2023Document3 pagesCaso 2 - Gerencia de Operaciones 2023Eyner PeñaNo ratings yet

- Manual On Financial Management of Barangays MODULE 2Document29 pagesManual On Financial Management of Barangays MODULE 2vicsNo ratings yet

- A Study On Supply Chain Management in Construction: Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesA Study On Supply Chain Management in Construction: Literature ReviewMoidin AfsanNo ratings yet

- Chopra Scm5 Ch01 GeDocument33 pagesChopra Scm5 Ch01 GeJAVIER ENRIQUE MU„OZ QUIROZNo ratings yet

- Module 1 - SCM (18me653) PDFDocument18 pagesModule 1 - SCM (18me653) PDFVIDYA PNo ratings yet

- Test Bank 3 - Ia 1Document25 pagesTest Bank 3 - Ia 1JEFFERSON CUTE100% (1)

- SQC A2 Group 8Document4 pagesSQC A2 Group 8SHARDUL JOSHINo ratings yet

- Bos 54380 CP 6Document198 pagesBos 54380 CP 6Sourabh YadavNo ratings yet

- Degree Thesis of Zobayer Hosen - A Business Plan For Establishing A Bangladeshi Restaurant in FinlandDocument59 pagesDegree Thesis of Zobayer Hosen - A Business Plan For Establishing A Bangladeshi Restaurant in FinlandAhmed Al MasudNo ratings yet

- 2MBA Biz PlanDocument22 pages2MBA Biz PlanCarinna Saldaña - PierardNo ratings yet

- Lot SizingDocument9 pagesLot SizingZerlynda Ganesha IskandarNo ratings yet

- Inventory Tables3Document3 pagesInventory Tables3KrishnaChaitanyaChalavadiNo ratings yet

- 412 33 Powerpoint-Slides Chapter-17Document20 pages412 33 Powerpoint-Slides Chapter-17Kartik KaushikNo ratings yet

- MAS Variable Absorption Consultation HODocument2 pagesMAS Variable Absorption Consultation HOCeline RiveraNo ratings yet

- OpmDocument15 pagesOpmMuhammed Dursun ErdemNo ratings yet

- REPORT Ayush Choudhary 0901AU171023Document59 pagesREPORT Ayush Choudhary 0901AU171023ayush247No ratings yet

- Bac 412 - Advacc2-Reviewer For Final Departmental ExamDocument11 pagesBac 412 - Advacc2-Reviewer For Final Departmental ExamAudreyMaeNo ratings yet

- Royal Company Budgeting - With Additional DetailsDocument3 pagesRoyal Company Budgeting - With Additional DetailsSonakshi BhatiaNo ratings yet

- Logistics Project ReportDocument67 pagesLogistics Project ReportJadeja Hiralba0% (1)

- Working Capital Management: MenuDocument11 pagesWorking Capital Management: MenuMuhammad YahyaNo ratings yet

- Operations Manager Logistics Distribution in Philadelphia PA Resume Jeffrey WassermanDocument2 pagesOperations Manager Logistics Distribution in Philadelphia PA Resume Jeffrey WassermanJeffreyWassermanNo ratings yet

- Warehouse Clerk Job Description 2-16-2012Document2 pagesWarehouse Clerk Job Description 2-16-2012ResponsiveEdNo ratings yet

- Determining The Optimal Level of Service (Product Availability)Document2 pagesDetermining The Optimal Level of Service (Product Availability)Deepankar Shree GyanNo ratings yet

- Acknowledgement: Prof.N.RAMACHANDRAN, For Helping To Bring Successfully and For Strengthening The Ray ofDocument6 pagesAcknowledgement: Prof.N.RAMACHANDRAN, For Helping To Bring Successfully and For Strengthening The Ray ofSatz TradesNo ratings yet

- Ican b2 Aa Mock As 2019 v2Document15 pagesIcan b2 Aa Mock As 2019 v2demshubedada472No ratings yet