Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Untitled

Uploaded by

api-106078359Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Untitled

Uploaded by

api-106078359Copyright:

Available Formats

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

COVER PAGE -UOM JOURNAL FORMAT

Implementing a Customs Union Agreement : Prospects for a Small, Late Comer, Land-locked Country- Rwanda in the East African Community

By Prof. A.V.Y. Mbelle (Ph.D)

Department of Economics, University of Dar es Salaam; P.O. Box 35045 Dar es Salaam

Tel.: 022 2410500 - 8 Ext. 2262 2410252 - Direct Line Fax: 022 2410162 Telegram: University of Dar es Salaam 022 E-mail: doe@udsm.ac.tz Website: www.economics.udsm.ac.tz

Mobile: 0784-444-453 Personal e-mail: profammon.mbelle@gmail.com Prof. A.V.Y. Mbelle (Ph.D) 10/4/2012

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

IMPLEMENTING A CUSTOMS UNION AGREEMENT: PROSPECTS FOR A SMALL LATE COMER LAND-LOCKED COUNTRY - RWANDA IN THE EAST AFRICAN COMMUNITY

A Partial Equilibrium Model Approach

Author: Prof. A.V.Y. Mbelle (Ph.D) Department of Economics, University of Dar es Salaam P.O. Box 35045, Dar es Salaam; Tanzania

Abstract

Regional Trading Arrangements evolved out of challenges of implementing greater multilateral liberalization within the context of the World Trade Organizationand the need to go beyond the trade agenda to deeper integration. One of the key instruments in a regional integration is the Customs Union an agreement by partner states to adopt a Common External Tariff, over and above Free Trade Area arrangements. The EAC Customs Union came into force on 1st January, 2005 with Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania as the initial members. Rwanda started implementing the EAC Customs Union on 1stJuly 2009. Implementation of a customs union, not least the EAC Customs Union,faces many challenges, prime being the cost and benefits of joining. This paper assesses the gains for Rwanda out of implementing the East African Customs Union using a Partial Equilibrium model. Revenue loss is found to be the main cost of implementing the Customs Union. However, Rwanda experiences welfare gains. The paper argues for staying the course of the East Africa Customs Union since increased benefits are realized with time as integration deepens.[156 words]

KEY WORDS: Regional Integration, Benefits, Small Country

ii

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

I: INTRODUCTION

1.1 Regional Trade Arrangements Regional Trade Arrangements (RTAs) have received great attention in policies of countries after World War II (WW II) mainly out of problems experienced with multilateral liberalization under the World Trade Organization (WTO). The problems center mainly around narrow focus on trade on trade(removing barriers to free trade in the region, increasing the free movement of people, labour, goods, and capital across national borders). Indeed the plight of many countries especially in the developing world dictates the need to go beyond mere trade issues to a broader development agenda. Today,regional blocs are dominating the globalized economic and financial system (Cameron 2010). In the African continent, Regional integration, a logical outcome of RTAs, has come to be seen as an important factor that will facilitate economic development and economic convergence. It is thus no accident that a number of integration schemes exist in the continent. By 2011 there were eight Regional Economic Communities and six other integration blocks recognized by the African Union (AU). Most African countries belong to more than one such arrangement. Multi belonging to regional arrangements have costs. Resources and capacity for negotiation become stretched. There are administrative costs related to often complex Rules of Origin. Multiple membership fees are expensive to pay and maintain. Conflicting objectives among rival arrangements have the potential of slowing progress in some areas. This notwithstanding, within the Abuja Treaty (1995) framework, a common market for Africa is envisaged within thirty years (a moratorium for establishing new blocks was imposed). The

1

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

Treaty thus implicitly allows a country to belong to more than one block. In order to move to an all Africa Common Market, harmonization of regional integrations is inevitable. It is in this spirit that the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) and EAC Blocks are cooperating in harmonization of certain policies. De Rosa (1998)points out that Regional Integration Arrangements have been the subject of considerable economicanalysis over time. However, debate on the issue of gains from integration have not been conclusive especially for small countries and so called natural trading partners.

Integration is a difficult process with many setbacks and crises that have not spared even the most developed integration schemes like the European Union (Cameron 2010). The author points out four tenets that have guided the EU well over the years and enabled the institutions to survive many crises. These are consensus approach, leadership, political will and visionary politicians. 1.2 Customs Union RTAs are governed through agreements, the most important one being the Customs Union (CU). In fact every Economic Union,has a Customs Union. Purposes for establishing a customs union normally include increasing economic efficiency and establishing closer political and cultural ties between the member countries.It is the third stage of economic integration. Andriamanjara(und.) points out that the rationale for choosing a CU overFree Trade Area (FTA), include political and economic ones. Some regional groupings consider the establishment of a CU a prerequisite for the future establishment of a political union, or at least some deeper form of economic integration, such as a Common Market (CM).

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

The history of CUs is traced by Strielkowski (2011)to the Zollverein formed by German states in the 1830s, followed by Benelux (Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg in) 1944 and European Economic Community (EEC)/European Union (EU) (Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and West Germany in 1957). In Africa, history is fading that the oldest CU to be formed was the East African Community Customs Union which came into force in 1919. Since then there have been a number of CUs coming to force, all over the World, and others becoming defunct (see Cameron 2010), while others undergoing metamorphosis (The North American Free Trade Agreement, adopted in 1992, an outgrowth of the 1988 Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement (and earlier Canada-U.S. trade cooperation pacts).

1.3 Problem statement Literature on thebenefits and costs of a CU is quite rich, mostly weighing for benefits. Within a CU there are pronounced differences among member countries in terms of all characteristics. There are a lot of early warnings given to certain groups of countries (land-locked, small) on costs overweighing benefits. Such countries have often doubted their gains in such groupings. Are such countries likely to gain from a CU?

1.4 Objective of Paper

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

The main objective of this paper is to analyze the effect of regional agreements viz CU in the context of the East African Community (EAC) so chosen because it exhibits unique features perhaps not seen in other integration schemes.

1.5 Organization In addition to the introduction section, five other sections form this Paper. Section two is devoted to background, focusing on the East African Community (EAC) and Rwanda, the country of analysis (chosen for the increasing research focus in recent years over all other EAC member countries). In section three we present both theoretical literature and empirical literature of the impact of a CU. Issues of methodology are discussed in section four. Section five is devoted to reporting empirical results while the last section to concluding remarks.

II BACKGROUND

2.1 The East African Community Customs Union The East African Community (EAC) is perhaps the only RTA which provides perfect lessons. It has had three successive CUs coming into force: 1919, 1967-1977 and 2005 with Kenya, Tanzaniaand Uganda as founding members. The Community started with building of a common service,Uganda Railways in 1895 and establishment of a Customs CollectionCentre in 1900; currency board in1905. In post- independence era, the East African community was formed (again) in 1967, and reached a Monetary Union. However in 1977 the EAC collapsed largely due to issues of sharing of benefits and political misunderstandings. Assets of the Community were all shared among the three member states. In 1992 an agreement to revive the EastAfrican cooperation treaty was reached. In 1996 a Secretariat was formed and later transformed into a

4

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

Community in 2000. Another unique feature of EAC is that even beforebecoming a Customs Union, it had already established related institutions. EAC+5 On 18th June, 2007 the Republic of Rwanda and the Republic of Burundi acceded to the EAC Treaty and became full members of the EAC Community effective 1st July 2007, bringing the number of members to five. The addition compounded diversity of members as shown in Table 1. As Table 1 shows there is great diversity among EAC countries. In terms of the economy, Kenya is dominant and Burundi is least. With regard to land area, Rwanda has least share of only one percent. The EAC also has differentiated tariff structures as shown in Annex 2. In addition, the EAC is composed of few countries, with the majority of countries being land-locked.

Table 1: Diversities AmongEast African Community Member Countries

Member/aspect Population (million) Poverty incidence (%) Share of EAC economy Land area (% of total) Political independence Real per capita GDP 2012 ($ 2010) Global rank, Doing Business,2011 Political independence Burundi 9 70 (2010) 1.9 2.0 1962 123 181 1962 Kenya 41 46 (2006) 37.1 33.0 1963 491 98 1963 Rwanda 11 45 (2011) 8.2 1.0 1961 394 58 1961 Tanzania 45 33 (2007) 27 52.0 1961 494 128 1961 Uganda 34 25 (2010) 25.8 12.0 1962 391 122 1962

Sources 1.IMF 2011 2.Ladegaard, 2012; 3.SID 2012.;4. authors computations

The EAC CU is based on three pillars: Common External Tariff (CET), Non-Tariff Barriers (NTBs) and Rules of Origin (RoO) (Gupta 2012).The focus of this study is on the former being the linchpin in integraation.Suffice it to point out here that a number of challenges are identified with respect to NTBs and RoO (EAC 2009, 2011).

5

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

The EAC CET is defined at the eight-digit code of the Harmonized System (HS) as transposed to the EAC level. Rates above 25% apply to the items on the Sensitive Items (SI) list. These high tariffs are related to lines covering dairy goods (60%), wheat (35% to 75%), sugar (100 %) and a few consumer goods - (cigarettes 35%), matches (50%), worn clothing, and other worn articles. These are activities for which Rwanda (and Burundi) had lower tariff rates. The EAC Customs Union Management Act governs the management and administration of Customs and related matters including: administration of the Common External Tariff; enforcement of the Customs law of the Community; trade facilitation as provided for in Article 6 of the Protocol; administration of the Rules of Origin; compilation and dissemination of trade statistics; application and interfacing of information technology in Customs administration; training in Customs related matters; quality control in Customs operations and enforcement of compliance; Customs related negotiations; and implementation of this Act(EAC2009). The Fifth Schedule (s. 114) prescribes the exemptions regime and delineates the privileged persons and institutions. Member countries are prohibited from choosing exemptions not detailed in the Fifth Schedule. Rwanda in EAC+5 Rwandas Vision 2020 (Rwanda, 2000) and the Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy (EDPRS), (Rwanda, 2007) define the countrys overall national development strategy. Trade has been mainstreamed in the governments policy documents for, among other measures to stimulate economic growth and development(UNCTAD/MTI 2010). activities of the Commissioners in the

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

Rwandas development-driven trade policy emphasizes strengthening of Rwandas participation in regional and internationaltrade and derive developmental gains in terms of job creation, welfare improvement and poverty reduction,as well as transformation from an agrarian to a knowledge-based economy. Rwanda joined the EAC CU in 2009. This meant that Rwanda had to: replace its customs law with the EAC Customs Management Act (CMA); harmonize its customs exemptions with the rules described in the Fifth Schedule of the CMA. Over 50 percent of Rwandas imports pass through Tanzania and Uganda (IGC 2011).This raises the challenge of operational arrangements now that the EAC is treated as a single market. Melo (2010)makes an assessment of Rwandas trade regime to be characterized by: low trade ratios for goods, low, diversification across products and geographic markets, and new exports seemed to die quickly. The author points out tofour areas that might merit additional policy discussion: infrastructure, reducing trading costs, leveraging regional trade agreements, and management of real exchange rate. Melo and Collinson (2011) further point out that Rwanda needs to factor in the costs associated with implementation (e.g. Rules of Origin) of the multiple RTAs it is engaged in.Rwanda also has one of the highest trade costs in the world (48 percent of export value compared to 14 percent averages for landlocked countries and 17 percent for LDCs). The authors further point out that prior to joining the CU, Rwanda had a higher average tariff (19 percentcompared to 12 percent for the EAC) and with less variance. In the EAC CU, SI list, products comprise less than 1 percent of tariff lines. However, these products accounted for 22 percent of Rwandas imports in 2006, compared to less than 6 percent

7

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

for the existing EAC members. Fifty percent of Rwandas imports were products with CET rates of at least 25 percent in 2006, while for Kenya and Tanzania this figure was 15 percent (Uganda was 23percent) (Melo and Collins, 2011).The authors further point out that for newcomers, from a resource allocation point of view, joining the EAC is only worth it if adopting the CET is accompanied by a removal of the SI list, i.e. by setting the tariff on the items on the SI list at 25% or less. There is, however, one caveat. The welfare gain comes at the expense of a loss in tariff revenue. Rwanda has had considerable trade relations with EAC countries before joining the scheme as shown in Table 2, much so for exports though declining later. Imports have been rising over time.Rwanda became less dependent on EAC as an export market over the period 2001-2011, while the opposite holds for imports.

Table 2: Rwandas Trade Intensity*: EAC and Rest of the World, 2001/02-2010/11

Region/Year Exports EAC RoW EAC/RoW Imports EAC RoW EAC/RoW 16.0 84.0 19.0 18.2 81.8 22.2 21.0 79.0 26.6 16.5 83.5 19.8 27.0 73.0 37.0 30.6 69.4 44.1 29.7 70.3 42.2 27.6 72.4 38.1 31.0 69.0 44.9 22.7 77.3 29.4 43.0 57.0 75.0 52.7 46.3 113.8 89.3 10.7 834.5 53.8 46.2 116.5 27.0 73.0 37.0 25.9 74.1 35.0 27.0 73.0 37.0 21.5 78.5 27.4 24.6 75.4 32.6 23.1 76.9 30.0 2001/02 2002/03 2003/04 2004/05 2005/06 2006/07 2007/08 2008/09 2009/10 2010/11

*Trade intensity is measured as a countrys total exports or imports in relation to its exports to the rest of the world or to the integration scheme. It is an indicator of how the countrys trade is dependent on the region .

Source: computed using official data

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

When Rwanda joined the EAC, about 56.6 percent of its trade was with the EAC. At the time of adopting the EAC CU the share was 55.6 percent.

III LITERATURE REVIEW

It must be pointed out from the beginning that literature on the subject matter of this paper is too rich and too diverse to be exhaustively covered in a brief paper like this one. A modest attempt has thus been made to only reflect works that have a direct bearing.

Theoretical The pioneering work "customs union issue" by Viner (1950) has inspired considerable theoretical and empirical work on the effects of CUs, especially byintroducing welfare consideration into the theory of international trade in general and particularly into the theory of Customs Unions.Viner considered trade diversion as switch in trade from less expensive to more expensive producers and trade creation as switch in trade from more expensive to less expensive producers. Meade (1955) developed this further by bringing in the reality of many countries in many commodities. Johnson (1965) expanded this further by introducing the concept of welfare.

Johnson (1965) suggested that the concept of trade diversion and trade creation should be more precisely defined on the basis of welfare effects rather than in terms of trade flows. Definition of trade creation was improved to welfare change due to the replacement of higher cost domestic production and/or higher cost imports by lower-cost imports, andtrade diversion to welfare change due to the replacement of imports from a low cost source by imports from a higher cost

9

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

source. In terms of world allocation of resources, trade creation is beneficial to welfare, while trade diversion worsens allocation.ACustoms Union is thus economically justified if it leads to trade creation, while a Customs Union generating a trade diversion leads towards a deeper protectionism and decrease of efficiency.

One of the areas of particular concern in a CU is revenue loss. There are two main channels through which adopting a CET impacts a member country: first, changes in tariff rates for regional imports and second, change in import flows. Both, in turn, induce effects on domestic tax receipts (excise and VAT) collected on imports depending on factors such as the countrys tariff levels prior to joining a CU, the CET, etc.

De Rosa (1998) reviewed the static theory of regional integration arrangements, pointing out that the basic Viner model provides a partial equilibrium framework for considering theeffects of Customs Unions. The framework consists of economic relationships depicting demand,supply, and trade in homogeneous goods (for final consumption) by three representativecountries: the home country (H), a partner member country (P), and a non-member country (N)representing the rest of the world.

The economic size of countries joining a regional integration arrangement has been ofconsiderable interest, the question being whether a small country can expect to gain and relatedly whether natural trading partners can gain more fromforming a regional integration arrangement (De Rosa, op.cit).

10

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

Castro et al(2004) point out that implementing a CU impacts member country economies through various channels. Thenew tariff schedule will change domestic prices of imported goods and thus demand forimports by consumers and supply by domestic producers of such goods. Changes in tariffrates for Most Favored Nation (MFN) and regional imports, together with the change in import flows, will affectcustoms revenue. The aggregate effect, which is the sum of change in revenue, change in consumer surplus, and change in producer surplus,will determine whether the formation of the CU haspositive or negative welfare effects.

The authors further stress that the impact of a change in MFN tariffs on import demand is straightforward. If thetariff is lowered, import prices decline and imports expand; if MFN tariffs are increased imports decline.Demand elasticities will determine the extent.The impact of forming a CU on customs revenue is in general undetermined; it dependson a countrys tariff levels prior to joining a CU, the CET, import demand elasticities, andexport supply elasticities in the CU member states.

Srielkowski (2011) points out that a Customs Union theory builds on strict assumptions such as perfect competition in commodity and factor markets and hence it is often referred to as orthodox Customs Union theory. It also only deals with the static welfare effects of a Customs Union. The pillars of a CU are elimination of tariffs on imports from member countries, adoption of a common external tariff on imports from the rest of the world and apportionment of customs revenue according to an agreed formula. Customs Union has both positive and negative welfare effects, compared to a situation in which every member state is practicing protectionism.

11

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

In terms of numbers and size, Strielkowski (op.cit) points out that the scope for benefiting in an integration scheme is larger for larger economic area and where membership is more numerous.Melo (2010) points out that Regional trade agreements have to be designed to promote deep integration otherwise smallest members suffer.The gains from integration are likely to be greater, the greater is the ratio of intra-trade (trade with future partners) to total trade. Empirical In assessing the trade and welfare effects of Customs Unions and Free Trade Areas, the functional form of demand systems employed in economic models can matter importantly. Melo and Collins (2011) point out that traditionally, RTAs have been analyzed in terms of the effects that tariff preferences have on trade flows between partners and non-partners. However, regional trade blocs always have multiple objectives. The studies that are reviewed here combine both

De Rosa (1998)provides a rich documentation of "evidence" from the quantitativestudies of recently established or revitalized regional integration arrangements. The author found that almostall point to the conclusion that regional trading arrangements established since1990 are trade-creating on a net basis and welfare-improving for member countries and tradingblocs as a whole. Static welfare gains of regionalintegration arrangements for especially less developed countries are modest at best (less than 0.3percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per annum). For advanced countries, quantitative results found using Computable General equilibrium (CGE) models are more favorable, at least in the case of regional integration under the Europe 1992 Plan(welfare gains of 1.0-to-2.0 percent of GDP per annum).

12

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

Madete (2010) investigated the effects of joining customs unions on member countries' Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) inflows using Panel data analysis of a restricted sample of 22 countries and large sample of 209 countries over the period 1970 to 2007. The author found that for most part, joining a Customs Union has positive effect on FDI inflows that member countries receive. The author also found that the length of time that a country has been in a CU is also important. Draper et al (2006) made an analysis of the impact on South Africa, deemed indispensable for any economic integration in the SADC region (accounting for about 60 per cent of SADC total trade and about 70 per cent of SADC GDP).Results of the analysis of trade creation and trade diversion showed the products with highest trade diversion to be tobacco, cotton, apparel articles and vehicles. The results are not surprising given that in all these products the SADC tariff was much lower than the MFN rate. High MFN tariffs protect producers from potential more efficient ROW exporters, thus leaving the South African consumer to bear the cost. In terms of trade creation the authors found no net trade creation, only lower trade diversion implying no new trade created and no significant displacement of South African producers. Total trade creation was South African Rand (SAR) 300 million, trade diversion SAR670 million and net trade diversion SAR370 million. Hallaert (2007) used a CGE framework to simulate the impact of SADC FTA on the Republic of Madagascar. The results suggested that the SADC FTA had a limited impact because of the small share of SADC imports. Textile and clothing sector benefited. However gains became substantial with multilateral liberalization. Mbelleet al 2007 in a study commissioned to propose a CET for SADC, simulated the impact of a CU in the 14 member SADC using a PE model. A total of 140 equations were estimated, ten

13

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

for each country. Simulation of the effect of tariff change on welfare was done. Results showed a rapid decline in welfare resulting from tariff reduction from 40 percent to 25 percent. Tariff reduction below 25 percent will lead to unacceptable welfare losses. For the individual SADC member countries, results were more country-specific. For example, simulation of the impact of tariff reduction on revenue for Tanzania showed that: (i) A reduction of tariff from 40 percent to 25 percent leads to a reduction in revenue more gradually than the drastic/steep revenue loss emerging when tariff is reduced from 25 percent to 15 percent; (ii) At tariff rates of between 25 percent and 30 percent revenue loss is 576,058 units or 40 percent; (iii) Rates below 25 percent will lead to drastic revenue losses.

East Africa A World Bank study (2003), used a Partial Equilibrium model to compute changes in import flows for the proposed EAC CU.Simulations on tariff rates and timing of reductions were made. Assumptions governing the analysis were based on an agreement by the three East African countries (Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda) on Common External Tariffs as follows:0 percent for meritorious goods, raw materials and capital goods; 10 percent for intermediate goods and 25 percent for consumer goods.

14

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

Results of the analysis indicated increases in welfare for Kenya and Tanzania and decrease for Uganda out of trade diversion. Revenue implications indicated balanced costs and benefits for Kenya and Tanzania with Uganda slightly worse off. Castro et al, (2004)used a PE model to simulate EAC CU when the EAC countries had notyet agreed on the tariff classification for 474 items falling into two groups:sensitive products and non- sensitive products.The Harmonized System HS 8-digit level data were used.The study focused on two issues: the change in imports, regional andfrom third countriesthat will result from implementing the CU; and on the effect of the CUimplementation on customs revenue collection. The authors did not calculate consumer andproducer surplus. As such welfare impacts were only discussed in anticipation. The authors found modest increase in regional trade flows as a result of the CU implementation; increase in third country imports for Kenya and Tanzania because of tariff liberalization; modest decline in customs revenue (tariffs and domestic taxes on imports) from implementation. In terms of winners and losers, implementation of the CU was seen to lead to increases in welfare for the Kenyan and Tanzanianeconomies, driven by the reduction in import prices, which will benefit consumers and producers using imported inputs.The situation was different for Uganda, where CU implementation was to lead to more expensive imports for consumersand producers. In addition, Uganda was to lose revenue because of trade diversion. The authors recommended Tariff schedule with top rate at 20 percent as the preferred choice. Rwanda There have been a number of studies on Rwanda in the EAC+5. However almost all have dealt with flows of trade. The closest study to rigorous assessment is provided by Melo and Collins (2011).The authors found substantial loss in tariff revenue from joining the EAC (pointing out

15

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

that the losses were offset by fuel excise taxes, and short term payments from the COMESA Compensation Fund). Simulations by the two authors (before Rwanda adopted EAC CET) showed that: Moving without SI list: revenue loss was 8 percent and change in welfare +0.004 Moving with current list: revenue loss was 18 percent and change in welfare -0.0032 Moving with SI set at 25 percent: revenue loss was 17 percent and change in welfare +0.016

The important conclusion that these authors draw is that for newcomers, from a resource allocation point of view, joining the EAC is only worth it if adopting the CET is accompanied by a removal of the SI list, i.e. by setting the tariff on the items on the SI list at 25 percent or less.

IV METHODOLOGY There are a number of tools that can be used to assess performance in a CU. They can be used in isolation or in combination. The choice of a particular method will be mainly determined by availability of the appropriate data. The most common ones (in this order of sophistication) are Survey method approach, tariff analysis, analytical approaches, residual method (Ogunkola, 1998), measures of Trade Intensity, Revealed Comparative Advantage, PE models, CGEs, each with particular strengths and weaknesses. Estimation method

16

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

Following the review of empirical literature above, the Partial Equilibrium model was used because of its wide application and other strengths. Use of PE models has been wide. Castro et al, (2004)point out that these models are powerful quantitative tools to simulate and measure the effects of changes in trade policy. They can measure the effects of specific changes in tariffs or other trade taxes on trade flows,revenue, prices, and some measures of welfare at a given point intime. PE models allow for detailed product-by-product analysis and are fairly easy to set up and implement.

Analysis of trade creation or trade diversion includes domestic supply functions and changing the assumption that the MFN CET determines all import prices. The partial equilibrium analysis is the more appropriate model only that it is too demanding in terms of data. It rests on the premise that there are sectors in the scheme, in this case EAC, which are globally efficient and therefore the dominant supplier to the country in question, in this case Rwanda market prior to the formation of the CU. Thus, for those sectors where the EAC is the dominant supplier we can estimate the consumption effect alone ( MC) relative to the existing EAC import levels as follows:

t 1 t

D EAC .eM .M O. UVOEAC .......... .......... .......... .......... .....(1)

where t eDM

= current tariff imports from EAC = price elasticity of demand for imports current volume of imports from EAC current average unit value of imports from EAC

MoEAC = UVoEAC =

17

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

The revenue ( Rc) and welfare ( wc) effects associated with this are correspondingly: Trade diversion with consumption effects For imports where ROW is the dominant supplier, if P EAC< P1ROW then, given a constant cost technology over the relevant range, the CU will divert all imports for the ROW to the EAC. Thus, the upper limit of the value of trade diversion ( MTD) is:

W R

0.5t. M c .......... .......... .......... .......... .....( 3)

EAC EAC t.M O. M O .......... .......... .......... .......... .....( 2)

TD

ROW M O. UVOROW .......... .......... .......... .......... .....( 4)

whereMoROW = current quantity of imports from ROW UVoROW = current average unit value of imports from ROW PEAC= Price, East Africa P1 = Price Rest of the world

The tariff revenue effect ( RTD) due to this trade diversion is given by:

TD

ROW tM O. UVOROW .......... .......... .......... .......... .....( 5)

For these sectors there will also be consumption effects. The same general approach is used as above. However, since we do not have information about where the price of EAC imports may lie between P ROW and P1 ROW, we assume that on average PEAC lies halfway between the two.

Given the assumption about PEAC we can approximate the overall welfare (WTD) impact as trade

1 t diversion with consumption effects as follows:

TD

0.5

D ROW .eM .M O UVOEAC .......... .......... .......... .......... .....( 6)

18

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

TD

0.25t

ROW 0.5tM O. UVOROW .......... .......... .......... .......... .....( 7)

Trade creation with consumption effects For those sectors where a specific country from EAC is not a relatively minor supplier (i.e. provide greater than 25percent of imports) we estimate the effects of trade creation (i.e. source substitution) with consumption effects in analogous fashion to the trade diversion case. We assume now the EAC is a more efficient supplier than the ROW (if it is not, we would have a variant of the trade diversion case). If the duty free supply price from the EAC lies over the relevant range between P1

ROW

and P

EAC

then all of the current imports from one country to

another country will be replaced by more efficient production from EAC. Thus the maximum value of the trade created ( M TC) for the EAC by this deflection from any of the countries from EAC sources can be estimated by:

TC

Ci Ci M O. UVO .......... .......... .......... .......... .....(8)

Where:MoCi = current quantity of imports from one of the EAC countries UVCi = current average unit value of imports from one of the EAC countries

TC

0.5

t 1 t

D Ci .eM .M O. UVOSADC .......... .......... .......... .......... .....( 9)

In order to estimate consumption effects in these sectors, we assume that the price from one of the EAC countries is virtually as high as the tariff-inclusive price from EAC. In this case the pre-CU tariff rate against EAC imports provides an (upper) estimate of the extent to which the import price can fall as result of a CU. Thus:

19

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

TC

0.5t

TC

Ci Ci ( M O. UVO .t )......... .......... .......... .......... ......(10)

In turn, the combined welfare (AWTC) effects of trade creation with consumption effects can be identified. The sector estimates can be aggregated to produce overall estimates of the value of trade effects due to consumption, trade diversion and trade creation. The corresponding revenue and welfare effects can be aggregated across sectors, and a net aggregate welfare effect estimated for a move to a CU for each country Data and data sources This study used the EAC s CET as defined at the eight-digit code of the Harmonized System (HS)as transposed to the EAC level. The main sources of data were official Rwanda government statistics, WTO and a number of research works. Data on demand and supply elasticities are in many countries provided by the Central Bank of the country. This is not the case for Rwanda. Hence we used the average for developing countries.

20

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

IV RESULTS

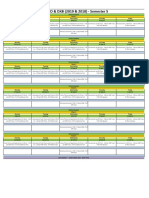

The main results of our analysis are presented in Tables 4.1 and 4.2 and Annex 3.

Table 3:

Results: Rwanda Change in Consumption, Revenue and Welfare from change in CET in EAC Countries (francs)

Change in CET Rate from 40% to 25% Change in CET Rate From 25% to 15% 475,454,000 -767.939,000 104,006,000 Change in CET Rate From 15% to 0%

1. Consumption Effect 2. Revenue Effect (negative) 3. Welfare Effect (positive)

585,828,000 -1,151,908,000 219,685,000

566,017,000 -767,939,000 58,724,000

The EAC customs union leads to an increase in consumption of imports in all the three CET rate change scenarios with the biggest impact being an increase of Rwanda Francs (Frw) 586 million at a CET change of 40 percent to 25 percent, the smallest impact would be an increase of 476 million francs at CET change of 25 percentto 15 percent. The customs union is estimated to decrease revenues collected from imports in all three CET change scenarios with the biggest decline in revenues being Frw1.2 billion at a CET change of 40 percentto 25 percent. The overall welfare effects are positive in all the three CET rate change scenarios. The Customs Union produces gains for consumers, though government revenue from imports declines. Trade creation and trade diversion effects The results from trade diversion show that, Rwanda was importing cheaper goods and services from ROW, which are replaced by expensive imports from within the Customs Union members. At the same time expensive domestically produced goods are replaced by cheaper imported goods from Customs Union members. However, since the overall results indicate a small benefit,

21

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

then the implication that can be drawn is that, negative welfare effect resulting from trade diversion is almost compensated by positive welfare effect from trade creation. The overall benefit was 0.05 percent when the tariff rate is changed from 40 percent to 25 percent compared to 0.04 percent when it changed from 25 percent to 15 percent. The minimum welfare benefit of 0.03 percent was recorded when the tariff rate changed from 15 percent to 0 percent (Table 4). The overall welfare benefit was dropping marginally from tariff change in high band rate to lower band rate.

Table 4: Results - Rwanda: Change in Welfare with Trade Creation and Trade Diversion (%) from Change in CET in EAC

Change in CET Rate from 40% to 25% Welfare Effect with Trade Diversion (-ve) Welfare Effect with Trade Creation (+ve) OVERALL (1+2) 37.45% 37.50% 0.05%

Change in CET Rate From 25% to 15% 39.96% 40.00% 0.04%

Change in CET Rate From 15% to 0% 66.64% 66.67% 0.03%

The results from trade diversion are that, Rwanda was importing cheaper goods and services from ROW, which are replaced by expensive imports from within the Customs Union members.

Comparison with other results

Our results compare well with the results of studies reviewed by De Rosa (1998). Our results compare well with those of Melo and Collins (2011) in terms of unambiguity of revenue loss; and welfare gains except for their moving with current list scenario.

V: CONCLUSIONS, LESSONS, LIMITATIONS AND AREAS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

22

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

Conclusions After joining the EAC CU Rwanda experienced implicit rise in tariffs,narrowing of tariff bands andloss of revenue. Rwanda joined the EAC CU with all odds: a small country, low ratio of trade with future partners, shorter time of being in the EAC CU thus a new comer. Despite all these the country gained overall. Lessons Perhaps the main lesson that Rwanda provides is that despite all odds, a country can gain out of a CU. Perseverance is an important lesson from other schemes as benefits are more dynamic in nature as integration deepens. Limitations The first limitation of this paper is the use of a Partial Equilibrium model. As Castro et al (2004) point out,PE models are static in nature, allowing only for a comparative static comparison ofpre- and post-policy change when all other variables are held constant. Thus, the dynamics that effect the changeare not explicitly modeled, and complex variations in the set-up cannot be considered. Since the model looks atthe partial effectsthat is, for one set of marketsof a policy change, PE models do not capture importantfeedbacks between markets.

In our study, preference of PE model over CGE was dictated by the period since Rwanda joined the EAC CU being too short to enable analysis of dynamics.

23

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

This shortcoming notwithstanding, we are confident that the results obtained are the best given the circumstances.

Areas for further research To the best of our knowledge this is the first study to analyze effects of the EAC+5 CU ex-post, using a Partial Equilibrium framework. Within the confines of time, a study on Burundi is recommended in light of the twin facts that these two countries are small and joined the CU at same time. With passage of time some further work could use other models such as CGEs. The EAC CU is based on three pillars: Common External Tariff (CET), Non-Tariff Barriers (NTBs) and Rules of Origin (RoO).The focus of this study has been on CET. Other studies may look into the other two issues.

References ANDRIAMANANJARA, S (und.) Customs Unions mimeo. CAMERON, F.(2010). The European Union as a Model for Regional Integration mimeo. CASTRO, L., C. KRAUS AND M DE LA ROCHA. (2004). Regional Trade Integration in East Africa:Trade and Revenue Impacts of the Planned East African Community Customs Union World Bank, African Region Working Paper Series, 72. DE ROSA, D.A.(1998).Regional Integration Arrangements: Static Economic Theory, Quantitative Findings and Policy Guidelines World Bank Policy Research Report. DRAPER, P., P. ALVES AND M. KALABA.(2006).South Africas International Trade Diplomacy Implications for Regional Integration, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Botswana.

24

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

EAST AFRICAN COMMUNITY.(2009). East African Community Customs Union (Rules of Origin) Rules, Arusha. EAST AFRICAN COMMUNITY.(2011). EAC Status of Elimination of Non-Tariff Barriers (NTBs), EAC Quarterly Publication, EAC Secretariat, August. GRUBEL, H. G AND P.G. LLOYD. (1975).Intra-Industry Trade London: Macmillan. HALLART, J.J.(2007). Can Regional Integration Accelerate Development in Africa? CGE Model Simulations of the Impact of the SADC FTA on the Republic of Madagascar, IMF Working Paper WP/07/66. HARTZENBERG, T. (2011).Regional Integration in Africa World Trade Organization Staff Working Paper ERSD-2011-14. INTERNATIONAL FINANCE CORPORATION. (2011). Doing Business in the East African Community 2011, IFC/World Bank, WashingtonDC. INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND.(2010). Regional Economic Outlook Sub Saharan Africa, Resilience and Risks, World economic and Financial Surveys, Washington, October. INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND. (2011). Rwanda: Next Steps in Tax and Customs Administration Reform August. JOHNSON, H.G.(1965). An Economic Theory of Protectionism, Tariff Bargaining, and the Formation of Customs Unions.Journal of Political Economy 73 (June): 256-283. LADEGAARD, P. (2012). Improving the Investment Climate in the East African Community Using the Doing Business Surveys to Prioritize and Promote Reform Paper Presented at the IMF/EAC Conference on The EAC After 10 Years: Deepening EAC Integration, Arusha, February 27-28. MBELLE, A.V.Y., MABELE, R, MWINYIMVUA, H. (2004). Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA): Analysis of Adjustment Scenarios for Tanzania, European Union (EU), Brussels.

25

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

MBELLE, A.V.Y., MABELE, R, MJEMA, G., KILINDO, L, HEPELWA, AND E. KISANGA. (2007). Southern Africa Development CommunityCustoms Union: Compatibility of National Trade Policies, (SADC), Gabarone. MCKAY, A., C. MILNER AND O. MORRISSEY.(2000). The Trade and Welfare Effects of a Regional Economic Partnership Agreement (CREDIT). MADETE, L.R. (2010). "Regional Integration and FDI: A focus on Customs Unions" Fordham University. Paper AAI3431920. MEADE, J.E. (1955). The Theory of Customs Unions. Amsterdam: North-Holland. MELO, DE J. AND R. NEWFARMER. (2010). Using Trade to Grow: Lessons from International Experience for Rwanda, mimeo. MELO, DE J. AND L. COLLINSON. (2011). Getting the Best Out of Regional Integration: Some Thoughts for Rwanda, International Growth Center, 2011. Getting theWorking Paper 11/0886, November. OGUNKOLA, E.O. (1998).An Empirical Evaluation of Trade Potential in the Economic Community of West African States AERC Research Paper No.84, Nairobi. PRADHAN, M. (2012). Economic and Financial Integration in Europe, Recent Stresses and Policy Changes Paper Presented at the IMF/EAC Conference on The EAC After 10 Years: Deepening EAC Integration,Arusha, February 27-28. REPUBLIC OF RWANDA.(2000). Rwanda Vision 2020, Kigali. REPUBLIC OF RWANDA. (2007). Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy 2008-2012.Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs, Kigali. REPUBLIC OF RWANDA. (2010). Current Status of NTBs Along the Northern and Cenral Corridors (including the Kigali-Bujumbura Route), An Experiental Study Trip by the Ministry of Trade and Industry & Private sector Federation, November. REPUBLIC OF RWANDA.(2011). Draft Annual Activity Report for 2010/11, Rwanda Revenue Authority, September.

26

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

RWANDA PRIVATE SECTOR FEDERATION.(2008). Assessment of Non-Tariff Barriers (NTBs) Along the Northern and Central Corridors EAC, Baseline Study, Kigali. SEBREGONDI, F.C. (2012). Investment and Trade in the EAC, Progress and Priorities Paper Presented at the IMF/EAC Conference on The EAC After 10 Years: Deepening EAC Integration, Arusha, February 27-28. SOCIETY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT.(2012). The State of East Africa 2012: Deepening Integration, Intensifying Challenges Nairobi. STRIELKOWSKI, W. (2011).Economics of Customs Union Viners Model of Customs Unions IES mimeo. UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT (UNCTAD) AND MINISTRY OF INDUSTRY AND TRADE, RWANDA.(2010).Rwandas Development Driven Trade Policy Framework, New York and Geneva. UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR AFRICA.(2011).Economic Report on Africa, 2011: Governing Development in Africa the Role of the state in Economic Transformation. Addis Ababa. VINER, J. (1950). The Customs Union Issue, New York: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. WORLD BANK. (2003). Regional Trade Integration in East Africa Trade and Revenue Impacts of the Planned Customs Union, World Bank, Washington DC. WORLD BANK. (2011).2011 Doing Business Report, Making a Difference for Entrepreneurs, Washington DC. WTO/OMC/ITC/UNCTAD. (2011). World Tariff Profiles 2011: Applied MFN Tariffs, Geneva

Annex 1 Process of Economic Integration Free Trade Area (FTA) = Elimination of Tariffs between member states but maintain own external tariff on imports from the Rest of the World (ROW)

27

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

Customs Union (CU)

= FTA + Common External Tariff (CET)

Common market (CM) = CU + free mobility of capital and labour across countries (plus harmonized trading standards and practices; common trade policy towards third parties) Monetary Union = CM + Central Monetary Authority/common currency

Political Federation

Source: adopted from international literature

Annex 2: East Africa - MFN Tariff Structure at the HS 6 Level, 2010

Country Year of MFN Applied tariff Simple Average Binding coverage Bound MFN Applied Bound MFN Applied Bound MFN Applied Bound MFN Applied Duty free Non ad valorem duties Duties >15% Number of MFN Applied tariff lines

In % Burundi Kenya Rwanda Tanzania Uganda 2010 2010 2010 2010 2010 22 14.8 100 13.4 15.7 67.6 95.4 89.4 120.0 73.4 12.5 12.5 12.5 12.5 12.5 0.7 0 0.9 0 0

Share of HS 6 digit Sub heading in % 37.7 37.6 37.7 37.5 37.7 0 0 0 0 0 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 19.0 14.8 97.1 13.4 15.7 40.4 40.4 40.4 40.4 40.4 5,261 5,261 5,261 5,261 5,261

Source: Derived from WTO/ITC/UNCTAD World Tariff Profiles, 2011; Tables, pp6-11

28

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

29

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

Annex 3: Results of Estimations

Consumption Effects Only

Equation 1

Rate

0.40 0.35 0.30 0.25 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00

M =

1,952,759 1,771,948 1,577,228 1,366,931 891,477 621,332 325,460 0

t

0.40 0.35 0.30 0.25 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00

t/(1+t)

0.29 0.26 0.23 0.20 0.13 0.09 0.05 0.00

edm

0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89

MoEAC

18,459 18,459 18,459 18,459 18,459 18,459 18,459 18,459

UVoEAC

416.03 416.03 416.03 416.03 416.03 416.03 416.03 416.03

Equation 2

Rate

0.40 0.35 0.30 0.25 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00

R =

-3,071,755 -2,687,786 -2,303,817 -1,919,847 -1,151,908 -767,939 -383,969 0

-t

-0.40 -0.35 -0.30 -0.25 -0.15 -0.10 -0.05 0.00

MoEAC

18,459 18,459 18,459 18,459 18,459 18,459 18,459 18,459

UVoEAC

416 416 416 416 416 416 416 416

Equation 3

0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5

Rate

0.40 0.35 0.30 0.25 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00

0.5t

0.200 0.175 0.150 0.125 0.075 0.050 0.025 0.000

390,552 310,091 236,584 170,866 66,861 31,067 8,136 0

1,952,759 1,771,948 1,577,228 1,366,931 891,477 621,332 325,460 0

Trade diversion with Consumption Effects

Equation 4

MTD=

358,828,997

MoROW

410627.7

UVoROW

873.9

Equation 5

Rate

0.40 0.35 0.30 0.25 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00

RTD=

143,531,599 125,590,149 107,648,699 89,707,249 53,824,350 35,882,900 17,941,450 0

-t

0.40 0.35 0.30 0.25 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00

MoROW

410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7

UVoROW

873.9 873.9 873.9 873.9 873.9 873.9 873.9 873.9

Equation 6

Rate

0.40 0.35 0.30 0.25 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00

MTD=

21,720,280 19,709,143 17,543,303 15,204,196 9,915,780 6,910,998 3,620,047 0.00

0.5(t/(1+t))

0.1429 0.1296 0.1154 0.1000 0.0652 0.0455 0.0238 0.0000

edm

0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89

MoROW

410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7

UVoEAC

416 416 416 416 416 416 416 416

Equation 7

Rate

0.40 0.35 0.30 0.25 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00

W TD=

-71,570,524 -62,640,029 -53,706,057 -44,768,191 -26,878,744 -17,925,917 -8,966,657 0

0.25t

0.100 0.088 0.075 0.063 0.038 0.025 0.013 0.000

Minus

0.5t

0.20 0.18 0.15 0.13 0.08 0.05 0.03 0.00

MoROW

410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7

UVoROW

873.9 873.9 873.9 873.9 873.9 873.9 873.9 873.9

1,952,759 1,771,948 1,577,228 1,366,931 891,477 621,332 325,460 0

Trade Creation with Consumption Effects

Equation 8

MTC=

8,649,214

MoCi

29924.8

UVoCi

289.0

Equation 9

Rate

0.40 0.35 0.30 0.25 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00

MTC=

1,582,879 1,436,316 1,278,479 1,108,015 722,619 503,643 263,813 0

0.5(t/(1+t))

0.14 0.13 0.12 0.10 0.07 0.05 0.02 0.00

edm

0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89

MoCi

29924.8 29924.8 29924.8 29924.8 29924.8 29924.8 29924.8 29924.8

UVoEAC

416 416 416 416 416 416 416 416

Equation 10

Rate

0.40 0.35 0.30 0.25 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00

W TC=

5,189,528 4,540,837 3,892,146 3,243,455 1,946,073 1,297,382 648,691 0

0.5t

0.20 0.18 0.15 0.13 0.08 0.05 0.03 0.00

MTC

8,649,214 8,649,214 8,649,214 8,649,214 8,649,214 8,649,214 8,649,214 8,649,214

Plus

MoCi

29924.8 29924.8 29924.8 29924.8 29924.8 29924.8 29924.8 29924.8

UVoCi

289.0 289.0 289.0 289.0 289.0 289.0 289.0 289.0

t

0.40 0.35 0.30 0.25 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

Consumption Effects Only

Equation 1 0.30 0.25 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00 Equation 2 Rate Rate Mc= 1,577,228 1,366,931 891,477 621,332 325,460 Rc= -2,303,817 -1,919,847 -1,151,908 -767,939 -383,969 0 Wc= 236,584 170,866 66,861 31,067 8,136 t 0.30 0.25 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00 -t t/(1+t) edm 0.23 0.20 0.13 0.09 0.05 0.00 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 MoEACUVoEAC 18,459 18,459 18,459 18,459 18,459 18,459 416.03 416.03 416.03 416.03 416.03 416.03

MoEACUVoEAC -0.30 -0.25 -0.15 18,459 18,459 18,459 Mc 18,459 416 18,459 416 18,459 416 416 416 416

From 30% - 25% -383,9690.30 From 25% - 15% -767,9390.25 From 15% - 10% -383,9690.15 From 10% - 05% -383,9690.10 From 05% - 0% -383,9690.05 0.0 Equation 3 Rate 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.30 0.25 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00

-0.10 -0.05 0.00 0.5t

0.075 0.050 0.025 0.000

0.150 1,577,228 0.125 1,366,931 891,477 621,332 325,460 -

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

Trade diversion with Consumption Effects Equation 4 MTD= 358,828,997 MoROW 410627.7 UVoROW 873.9

Equation 5

Rate 0.30 0.25 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00

RTD= -t 107,648,699 89,707,249 53,824,350 35,882,900 17,941,450 Rate MTD= 17,543,303 15,204,196 9,915,780 6,910,998 3,620,047 -

MoROW 0.30 0.25 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 0.5(t/(1+t)) 0.1154 0.1000 0.0652 0.0455 0.0238 0.0000 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89

UVoROW 873.9 873.9 873.9 873.9 873.9 873.9 edm MoROW 416 416 416 416 416 416 UVoEAC

Equation 6 0.30 0.25 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00

410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7

Equation 7 19.96% 33.308% 100%

Rate 0.30 0.25 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00

WTD= -53,706,057 -44,768,191 -26,878,744 -17,925,917 -8,966,657 0

0.25t 0.075 0.063 0.038 0.025 0.013 0.000

Mc

Minus 0.5t

MoROW 0.15 0.13 0.08 0.05 0.03 0.00

UVoROW 873.9 873.9 873.9 873.9 873.9 873.9

1,577,228 1,366,931 891,477 621,332 325,460 -

410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7 410627.7

ICTI 2012

ISSN: 16941225

Trade Creation with Consumption Effects Equation 8 MTC= 8,649,214 MoCi UVoCi

29924.8 289.0

Equation 9 0.30 0.25 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00 Equation 10 16.67% 0.30 0.25 33.33% 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00

Rate

MTC= 1,278,479 1,108,015 722,619 503,643 263,813 -

0.5(t/(1+t)) 0.12 0.10 0.07 0.05 0.02 0.89 0.5t 0.15 0.13 0.08 0.05 0.03 0.00 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 0.89 29924.8

edm 29924.8 29924.8 29924.8 29924.8 29924.8 416

MoCi 416 416 416 416 416

UVoEAC

0.00

Rate

WTC= 3,892,146 3,243,455 1,946,073 1,297,382 648,691 -

MTC Plus 8,649,214 8,649,214 8,649,214 8,649,214 8,649,214 8,649,214

MoCi

UVoCi t 29924.8 29924.8 29924.8 29924.8 29924.8 29924.8 289.0 289.0 289.0 289.0 289.0 289.0 0.30 0.25 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00

You might also like

- UntitledDocument138 pagesUntitledapi-106078359No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument31 pagesUntitledapi-106078359No ratings yet

- Ramirez - ChicanafuturismDocument10 pagesRamirez - ChicanafuturismOlga 'Ligeia' ArnaizNo ratings yet

- Ramirez - ChicanafuturismDocument10 pagesRamirez - ChicanafuturismOlga 'Ligeia' ArnaizNo ratings yet

- Health Policies Impacts On Providers' Self-Esteem in Rwanda: Some Unexpected ResultsDocument2 pagesHealth Policies Impacts On Providers' Self-Esteem in Rwanda: Some Unexpected Resultsapi-106078359No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument12 pagesUntitledapi-106078359No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument133 pagesUntitledapi-106078359No ratings yet

- Rahsaan@polsci Umass EduDocument49 pagesRahsaan@polsci Umass Eduapi-106078359No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument28 pagesUntitledapi-106078359No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument218 pagesUntitledapi-106078359No ratings yet

- Intimate Partner Violence in Rwanda: A Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Survey Among Antenatal Care NursesDocument38 pagesIntimate Partner Violence in Rwanda: A Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Survey Among Antenatal Care Nursesapi-106078359No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument11 pagesUntitledapi-106078359No ratings yet

- A Review On Minorities' Religion in Iran's ConstitutionDocument6 pagesA Review On Minorities' Religion in Iran's Constitutionapi-106078359No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument43 pagesUntitledapi-106078359No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument99 pagesUntitledapi-106078359No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument25 pagesUntitledapi-106078359No ratings yet

- Impact Evaluation of The Ubudehe Programme in Rwanda: An Examination of The Sustainability of The Ubudehe ProgrammeDocument14 pagesImpact Evaluation of The Ubudehe Programme in Rwanda: An Examination of The Sustainability of The Ubudehe Programmeapi-106078359No ratings yet

- Oint TO Oint: ISSN 0882-4894Document43 pagesOint TO Oint: ISSN 0882-4894api-106078359No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument15 pagesUntitledapi-106078359No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument117 pagesUntitledapi-106078359No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument31 pagesUntitledapi-106078359No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument242 pagesUntitledapi-106078359No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument12 pagesUntitledapi-106078359No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument17 pagesUntitledapi-106078359No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument63 pagesUntitledapi-106078359No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument24 pagesUntitledapi-106078359No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument10 pagesUntitledapi-106078359No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument11 pagesUntitledapi-106078359No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument495 pagesUntitledapi-106078359100% (1)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Topic 2 - Australia's Place in The Global EconomyDocument19 pagesTopic 2 - Australia's Place in The Global EconomyKRISH SURANANo ratings yet

- Chapter 11 - Public FinanceDocument52 pagesChapter 11 - Public FinanceYuki Shatanov100% (1)

- The Pure International Trade Theory: Supply: February 2018Document28 pagesThe Pure International Trade Theory: Supply: February 2018Swastik GroverNo ratings yet

- Brand Names and Franchise Fees Suppose You Are Currently OperatingDocument2 pagesBrand Names and Franchise Fees Suppose You Are Currently Operatingtrilocksp SinghNo ratings yet

- Child labour in Africa highest of all regionsDocument2 pagesChild labour in Africa highest of all regionsRuel Gonzales100% (3)

- ICAO Doc 9184 Airport Planning Manual Part 1 Master PlanningDocument0 pagesICAO Doc 9184 Airport Planning Manual Part 1 Master PlanningbugerkngNo ratings yet

- Uber Technologies, Inc.Document2 pagesUber Technologies, Inc.OilandGas IndependentProject100% (2)

- CHAP19 Micro Foundation Mankiw 10edDocument55 pagesCHAP19 Micro Foundation Mankiw 10edAkmal FadhlurrahmanNo ratings yet

- Exchange Rate Management and Control: Rohit Oberoi Mba 4 Sem WFTMDocument22 pagesExchange Rate Management and Control: Rohit Oberoi Mba 4 Sem WFTMRohit OberoiNo ratings yet

- The Economic Feasibility of An Ultra-Low Cost AirlineDocument1 pageThe Economic Feasibility of An Ultra-Low Cost AirlineTshep SekNo ratings yet

- International MarketingDocument28 pagesInternational Marketingarnab_bhaskar100% (2)

- Money and Its Usage - An Analysis in The Light of Shariah - Final VersionDocument284 pagesMoney and Its Usage - An Analysis in The Light of Shariah - Final Versionojavaid_1100% (2)

- BEC SYD & DXB Online ScheduleDocument2 pagesBEC SYD & DXB Online ScheduleMinhChau HoangNo ratings yet

- What Is Balance of Payment'?: Export Is More Than Its Import SurplusDocument5 pagesWhat Is Balance of Payment'?: Export Is More Than Its Import SurplusnavreenNo ratings yet

- Question Bank: (020) 2447 6938 E MailDocument32 pagesQuestion Bank: (020) 2447 6938 E MailHardik BhondveNo ratings yet

- 503 MID Term Solved Papers WD RefDocument80 pages503 MID Term Solved Papers WD Refds1302003269892No ratings yet

- Lecture 10 Relevant Costing PDFDocument49 pagesLecture 10 Relevant Costing PDFAira Kristel RomuloNo ratings yet

- Jiwaji University Gwalior: Syllabus AND Examination SchemeDocument55 pagesJiwaji University Gwalior: Syllabus AND Examination SchemeShubham VermaNo ratings yet

- Ib ch4 To ch6Document25 pagesIb ch4 To ch6Teesha AggrawalNo ratings yet

- Fifteen: Target Costing and Cost Analysis For Pricing DecisionsDocument38 pagesFifteen: Target Costing and Cost Analysis For Pricing DecisionsApria99No ratings yet

- 1.the Advantages and Disadvantages of StatisticsDocument3 pages1.the Advantages and Disadvantages of StatisticsMurshid IqbalNo ratings yet

- Problem-1: End of Week 1 2 3 4 5 6 Probability of Failure To DateDocument9 pagesProblem-1: End of Week 1 2 3 4 5 6 Probability of Failure To DateKhiz Sam100% (1)

- Bu L5&6 CHDocument43 pagesBu L5&6 CHRichie ChanNo ratings yet

- Measuring Price and Quantity ChangesDocument30 pagesMeasuring Price and Quantity ChangesAfwan AhmedNo ratings yet

- PROMOTE TOURISM WITH SEO-OPTIMIZED CONTENTDocument29 pagesPROMOTE TOURISM WITH SEO-OPTIMIZED CONTENTMalik Mohamed100% (1)

- Grand Strategy Matrix Quadrant AnalysisDocument3 pagesGrand Strategy Matrix Quadrant AnalysisRusselNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of Economic Sectors: Primary, Secondary, Tertiary and QuaternaryDocument27 pagesThe Evolution of Economic Sectors: Primary, Secondary, Tertiary and QuaternarySohail MerchantNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Teaching Strategies and Performance of Students in Economics A Case Study of Selected Secondary Schools in Enugu StateDocument12 pagesAssessment of Teaching Strategies and Performance of Students in Economics A Case Study of Selected Secondary Schools in Enugu StateSir RD OseñaNo ratings yet

- Vision IAS Guide to Indian EconomyDocument3 pagesVision IAS Guide to Indian EconomyannaNo ratings yet

- Are Filipinos Natural Born GamblersDocument2 pagesAre Filipinos Natural Born GamblersCherryl KhoNo ratings yet