Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tax2 Palanc - Pirovano

Uploaded by

Jade SeitOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tax2 Palanc - Pirovano

Uploaded by

Jade SeitCopyright:

Available Formats

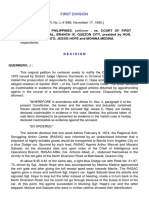

EN BANC [G.R. No. L-16661. January 31, 1962.] CLARA DILUANGCO PALANCA, ET AL., petitioners, vs.

COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE, ET AL., respondents.

SYLLABUS 1.TAXATION; COLLECTION; PERIOD OF LIMITATION; TO START THE RUNNING OF PERIOD; DISTRAINT OF LEVY. All that is required by the provision of Section 332 (c) of the National Internal Revenue Code to start the running of the period of limitation therein prescribed is to distrain or levy, or institute a proceeding in Court, within 5 years after the assessment of the tax. 2.ID.; ID.; WHEN JUDICIAL ACTION IS DEEMED COMMENCED. A judicial action for the collection of a tax is begun by the filing of a complaint with the proper court of first instance, or where the assessment is appealed to the Court of Tax Appeals, by filing an answer to the taxpayer's petition for review where in payment of the tax is prayed for. 3.ID.; ID.; DISTRAINT AND LEVY, HOW COMMENCED. The summary remedy of distraint and levy is begun by the issuance of a warrant of distraint and levy and it is not necessary that it be actually executed to be made effective. 4.ID.; ID.; EFFECT OF WARRANTY OF DISTRAINT AND LEVY. The right of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue to collect by summary method had the effect of stopping the running of prescription once a warrant of distraint and levy is issued. 5.ID.; ID.; INHERITANCE TAX WHETHER ASSESSED BEFORE OR AFTER DEATH OF DECEASED. An estate or inheritance tax, whether assessed before or after the death of the deceased, can be collected from the heirs even after the distribution of the properties of the decedent.

On March 5, 1952, the Commissioner of Internal Revenue issued a warrant of distraint and levy for the satisfaction of the deficiency, estate and inheritance taxes in the total amount of P24,790.21 informing thereof at the same time the register of deeds pursuant to the provisions of Section 104 of the National Internal Revenue Code. However, the warrant of distraint and levy was not executed because the executor of the estate asked for a reinvestigation of the case and for the placing of the real properties left by the deceased under constructive levy in order to obviate the necessity of having to file a surety bond to guarantee the payment of the assessed taxes. This request was granted and the case was again referred to examiner Testa for comment and recommendation. Considering the market value of the properties as appraised by C. M. Hoskins & Company, Inc. which was requested to do the appraisal by the heirs themselves, examiner Testa submitted a report on July 26, 1952, and on the basis thereof a new assessment was made calling for the payment of P10,437.76 on or before September 30, 1952. In view of this new assessment the Commissioner ordered the warrant of distraint and levy dated March 5, 1952 to be executed "except that the amount to be collected should be P10,437.76 instead of P24,790.21 stated therein." In his indorsement dated May 20, 1955, agent Manuel F. del Rosario reported that Atty. San Jose refused to receive the said warrant of distraint and levy and instead requested the suspension of the execution of said warrant in view of certain discrepancies he allegedly found in the amount of the deficiency transfer taxes. In view of this objection, another warrant was issued on June 23, 1955, which was served on the secretary of Atty. San Jose, but instead of paying the tax Atty. San Jose sent a letter requesting that the heirs be informed of the amounts that are respectively due from each with the assurance that upon receipt of the information requested the heirs would immediately make arrangement for the settlement of their tax liabilities. In compliance with this request the Commissioner in a letter to Atty. San Jose dated April 28, 1956 explained the breakdown of the amounts due from the heirs the total of which amounted to P13,884.78, inclusive of surcharges, interests and penalties. Atty. San Jose wrote another letter requesting reconsideration of this assessment but the same was denied by the Commissioner. In a letter dated September 23, 1957, the heirs again requested a revaluation of the properties of the deceased with the assurance that if the request is granted they would be willing to file the requisite surety bond and a waiver of limitations in accordance with the existing regulations, but before such request could be acted upon which they assured was not intended for delay, the heirs, thru counsel, made a turn-about by raising this time the defense of prescription alleging that the right of the Government to collect by summary method the estate and inheritance taxes in question had already prescribed. The answer of the Commissioner was that the right of the Government to collect has not as yet prescribed and that steps would be taken to sell the properties left by the deceased. On March 3, 1958, the heirs filed a petition for review with the Court of Tax Appeals disputing the right of the Government to collect the taxes in question on the ground of prescription. On November 24, 1959, the Court of Tax Appeals rendered decision holding that the right of the Government to collect the sum of P10,437.76 has not prescribed and ordered petitioners to pay respondent said amount, plus the corresponding interest thereon to the date of payment. Petitioners have appealed. Section 332 (c) of the National Internal Revenue Code provides in part: "Where the assessment of any internal revenue tax has been made within the period of limitation above prescribed such tax may be collected by distraint or levy or by a proceeding in court, but only if begun (1) within five years after the assessment of the tax . . . ." It will be noted from this provision that all that is required to start the running of the period of limitation therein prescribed is to distraint or levy, or institute a proceeding in court, within 5 years after the assessment of the tax. A judicial action for the collection of a tax is begun by the filing of a complaint with the proper court of first instance, or where the assessment is appealed to the Court of Tax Appeals, by filing an answer to the taxpayer's petition for review wherein payment of the tax is prayed for (Alhambra Cigar and Cigarette Manufacturing Company vs. The Collector of Internal Revenue, G. R. Nos L-12026 & L-12131, May 29, 1959). And the summary remedy of distraint and levy is begun by the issuance of a warrant of distraint and levy. This has been the practice long observed in the Bureau of Internal Revenue, and this practice had been taken cognizance of by this Court in a number of cases, wherein it held that the right of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue to collect by summary method has the effect of stopping the running of prescription once a warrant of distraint and levy is issued. (The Collector of Internal Revenue vs. Avelino, et al. L-9202, November 19, 1956; The Collector of Internal Revenue vs. Zulueta, et al. L-8840, February 8, 1957;

DECISION

BAUTISTA ANGELO, J p: Gliceria Diluangco died on April 18, 1947 and testate proceedings were filed with the Court of First Instance of Manila for her estate's settlement and distribution. Upon discovering that the executor failed to file the return required by law, the Commissioner of Internal Revenue required him to do so and on March 27, 1951 he filed the requested estate and inheritance tax return. The estate was tentatively assessed estate and inheritance taxes in the total sum of P9,705.61, including 25% surcharge for failure to file the return on time. Atty. Manuel V. San Jose, executor of the estate and counsel for the heirs of the deceased, requested reconsideration of the imposition of the 25%, which the Commissioner denied. Subsequently, Atty. San Jose again requested reconsideration of the imposition of the same surcharge. In a report submitted on August 25, 1951, internal revenue examiner Francisco E. Testa stated that the estate subject to tax amounted to P150,657.40 and not P67,187.86 as reported in the return and, accordingly, an assessment notice was issued calling for the payment of P22,533.46 as deficiency taxes. Atty. San Jose requested a reinvestigation of this assessment which was referred for comment to examiner Testa who however reiterated his recommendation because of the executor's failure to prove his claim relative to the incorrectness of the valuation of the properties.

Collector of Internal Revenue vs. Solano, et al. L-11475, July 31, 1958). From such pronouncement it can be inferred that the issuance of the warrant of distraint and levy begins the summary remedy of distraint and levy and that it is not necessary that it be actually executed to be made effective. Here it is admitted that the estate and inheritance taxes in question were finally assessed on August 18, 1952, and the warrant of distraint and levy was issued within the 5-year period prescribed in Section 331 of the National Internal Revenue Code from the time the return was filed. It is also admitted that the warrant of distraint and levy was issued by respondent on June 23, 1955, but that said warrant has not been fully executed in view of the request of counsel for petitioners for an itemized statement of the amount due from each heir and the assurance given by said counsel that upon receipt of respondent's reply the heirs will immediately make arrangement for the settlement of their shares. We, therefore, hold that the right of the Government to collect the estate and inheritance taxes in question has not yet prescribed because the warrant of distraint and levy for their collection was begun within the 5-year period prescribed by law from the date of the assessment of said taxes. Petitioners, however, contend that the issuance of the warrant in question cannot be considered as having begun the summary remedy of distraint and levy because (a) said warrant is defective and (b) it was not served upon the taxpayer in accordance with law. With regard to the first contention, petitioners allege that the warrant of distraint and levy is defective because (1) it does not contain any description of the property sought to be levied upon; (2) it was issued against the estate whose legal existence had long terminated; and (3) it states the amount due in lump sum and does not itemize the tax and penalty due from petitioners. And with regard to the second contention, the defect is made to consist in that the warrant was served not upon the taxpayer himself but upon one Arturo Cristi, secretary of Atty. Manuel V. San Jose, contrary to what the law provides that a warrant should be served upon the taxpayer himself except when he is absent from the Philippines.

distraint and levy if the proceeding is begun within five years after assessment. In this case, the distraint and levy proceeding was actually begun with the issuance of the corresponding warrant of distraint and levy and the service thereof to Attorney Manuel V. San Jose. It is true that the warrant has not been fully executed with the seizure and sale of any property subject to the lien, but it was not due to the voluntary desistance of respondent; rather it was because of the request of the then counsel for petitioners for a statement of the amount due from each heir and for an opportunity to make arrangement for the settlement of the obligation, which request was considered reasonable by respondent. Under the law, it is not essential that the warrant of distraint and levy be fully executed in order that it may have the effect of suspending the running of the statute of limitation upon collection of the tax. It is enough that the proceeding be validly begun or commenced and that its execution has not been suspended by reason of the voluntary desistance of the respondent. In our opinion, the warrant of distraint and levy of June 23, 1955 was validly issued and was duly served upon counsel for petitioners and, therefore, the five- year period for collection of the state and inheritance taxes in question was suspended. And it continued to be suspended up to the date when the present appeal was filed by petitioners on May 3, 1958. Accordingly, the right to collect said taxes has not prescribed." We agree to the foregoing view. Indeed, the record shows that the warrant was not actually executed or carried out with the seizure and sale of any property of the deceased, not because of any voluntary desistance on the part of respondent, but because of the many requests for postponement, reinvestigation, revaluation, or other matters which had the effect of delaying or postponing the execution of said warrant. Were it not for said requests for postponement or revaluation, the warrant would have been fully executed well within the period prescribed by law. Indeed, if by acceding to the request for postponement of a taxpayer the period of prescription would be allowed to run even if there is no voluntary desistance on the part of the tax collector, we would not only countenance the commission of an injustice but would place the collection of the tax at the mercy or caprice of the taxpayer to the prejudice of the Government. Such a theory certainly cannot be entertained. WHEREFORE, the decision appealed from is affirmed, with costs against appellants. [G.R. No. L-19865. July 31, 1965.] MARIA CARLA PIROVANO, ETC., ET AL., petitioners-appellants, vs. THE COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE, respondent-appellee.

Petitioners apparently confuse the warrant of distraint and levy with the certificate mentioned in Section 324 of the Tax Code. The warrant of distraint and levy is not the certificate referred to in said section. Said warrant is the order to distraint and levy upon the properties of the taxpayer. The certificate mentioned in Section 324 is one prepared and issued by the agent designated by the Commissioner of Internal Revenue to execute the order of distraint and levy. It is issued after the seizure of the property distrained and levied upon. In other words, the issuance of the warrant is merely the step that starts the summary proceeding while the seizure of the properties is the next step. It is for this reason that the warrant did not contain the details regarding the properties to be distrained or levied upon because they are only required in a certificate referred to in Section 324. As regards the claim that the warrant was issued against the estate which has no longer legal existence because the testate proceedings were already closed, suffice it to state that said warrant is a mere order to an agent of the internal revenue office to collect the tax either from the estate or from the heirs if said estate is already closed. It is well-settled that an estate or inheritance tax, whether assessed before or after the death of the deceased, can be collected from the heirs even after the distribution of the properties of the decedent (Pineda vs. Court of First Instance of Tayabas, 52 Phil., 805). The contention that the warrant is ineffective because it was not served upon the taxpayers themselves is also untenable considering that the same was served upon Atty. Manuel V. San Jose, or his secretary, who has always acted right along not only in behalf of the estate but also of the heirs of the deceased. While the law provides that said warrant should be served upon the taxpayer except when he is absent from the Philippines when it may be served upon his agent or upon an occupant of the property, there is nothing therein that would prevent the service to be made upon his authorized representative. Here it is admitted that Atty. San Jose was the duly authorized representative of the estate and of the heirs. With regard to the contention that the issuance of the warrant is not sufficient to begin the proceeding by summary method but that it is necessary that it be actually executed, the Court of Tax Appeals said the following on the point: "Section 332 of the Revenue Code provides that the collection of an internal revenue tax may be made by

Angel S. Gamboa for petitioners-appellants. Solicitor General for respondent-appellee.

SYLLABUS 1.TAXATION; GIFT TAX; DONATION OUT OF GRATITUDE FOR PAST SERVICES. A donation made by a corporation to the heirs of a deceased officer out of gratitude for his past service is subject to the donees' gift tax. 2.ID.; ID.; ID.; NO DEDUCTION FOR VALUE OF PAST SERVICES. A donation made out of gratitude for past services is not subject to deduction for the value of said services which do not constitute a recoverable debt. 3.ID.; ID.; ID.; GRATITUDE NOT CONSIDERATION UNDER TAX CODE. Gratitude has no economic value and is not "consideration" in the sense that the word is used under Section 111 of the Tax Code.

4.ID.; ID.; COLLECTION OF INTEREST AND SURCHARGE FOR DELAY IN PAYMENT OF TAX MANDATORY. Section 119, paragraph (b) (1) and (C) of the Tax Code does not confer on the Commissioner of Internal Revenue or on the courts any power and discretion not to impose the 1% interest monthly and the 5% surcharge for delay in payment of the gift tax already assessed.

DECISION

On September 13, 1949, the stockholders of the Company formally ratified the various resolutions hereinabove mentioned with certain clarifying modifications that the payment of the donation shall not be effected until such time as the Company shall have first duly liquidated its present bonded indebtedness in the amount of P3,260,855.77 with the National Development Company, or fully redeemed the preferred shares of stock in the amount which shall be issued to the National Development Company in lieu thereof; and that any and all taxes, legal fees, and expenses in any way connected with the above transaction shall be chargeable and deducted from the proceeds of the life insurance policies mentioned in the resolutions of the Board of Directors. On March 8, 1951, however, the majority stockholders of the Company voted to revoke the resolution approving the donation in favor of the Pirovano children. As a consequence of this revocation and refusal of the Company to pay the balance of the donation amounting to P564,980.90 despite demands therefor, the herein petitioners-appellants, represented by their natural guardian, Mrs. Estefania R. Pirovano, brought an action for the recovery of said amount, plus interest and damages against De la Rama Steamship Co., in the Court of First Instance of Rizal, which case ultimately culminated to an appeal to this Court. On December 29, 1954, this Court rendered its decision in the appealed case (v. 96 Phil. 335) holding that the donation was valid and remunerative in nature, the dispositive part of which reads: "Wherefore, the decision appealed from should be modified as follows: (a) that the donation in favor of the children of the late Enrico Pirovano of the proceeds of the insurance policies taken on his life is valid and binding on the defendant corporation, (b) that said donation which amounts to a total of P583,813.59, including interest, as it appears in the books of the corporation as of August 31, 1951, plus interest thereon at the rate of 5 per cent per annum from the filing of the complaint, should be paid to the plaintiffs after the defendant corporation shall have fully redeemed the preferred shares issued to the National Development Company under the terms and conditions stated in the resolutions of the Board of Directors of January 6, 1947 and June 24, 1947, as amended by the resolution of the stockholders adopted on September 13, 1949; and (c) defendant shall pay to plaintiffs an additional amount equivalent to 10 per cent of said amount of P583,813.59 as damages by way of attorney's fees, and to pay the costs of action." (Pirovano, et al. vs. de la Rama Steamship Co., 96 Phil. 367-368) The above decision become final and executory. In compliance therewith, De la Rama Steamship Co. made, on April 6, 1955, a partial payment on the amount of the judgment and paid the balance thereof on May 12, 1955. On March 6, 1955, respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue assessed the amount of P60,869.67 as donee's gift tax, inclusive of surcharges, interests and other penalties, against each of the petitioners-appellants, or for the total sum of P243,478.68; and, on April 23, 1955, a donor's gift tax in the total amount of P34,371.76 was also assessed against De la Rama Steamship Co., which the latter paid. Petitioners-appellants herein contested respondent Commissioner's assessment and imposition of the donee's gift taxes and donor's gift tax and also made a claim for refund of the donor's gift tax so collected. Respondent Commissioner overruled petitioners' claim; hence, the latter presented two (2) petitions for review against respondent's rulings before the Court of Tax Appeals, said petitions having been docketed as CTA Cases Nos. 347 and 375. CTA Case No. 347 relates to the petition disputing the legality of the assessment of donees' gift taxes and donor's gift tax while CTA Case No. 375 refers to the claim for refund of the donor's gift tax already paid. After the filing of respondent's usual answers to the petitions, the two cases, being interrelated to each other, were tried jointly and terminated. On January 31, 1962, the Court of Tax Appeals rendered its decision in the two cases, the dispositive part of which reads:

REYES, J.B.L., J p: This case is a sequel to the case of Pirovano, vs. De la Rama Steamship Co., 96 Phil. 335. Briefly, the facts of the aforestated case may be stated as follows: Enrico Pirovano was the father of the herein petitioners- appellants. Sometime in the early part of 1941, De la Rama Steamship Co. insured the life of said Enrico Pirovano, who was then its President and General Manager until the time of his death, with various Philippine and American insurance companies for a total sum of one million pesos, designating itself as the beneficiary of the policies obtained by it. Due to the Japanese occupation of the Philippines during the second World War, the Company was unable to pay its premiums on the policies issued by its Philippine insurers and these policies lapsed, while the policies issued by its American insurers were kept effective and subsisting, the New York office of the Company having continued paying its premiums from year to year. During the Japanese occupation, or more particularly in the latter part of 1944, said Enrico Pirovano died. After the liberation of the Philippines from the Japanese forces, the Board of Directors of De la Rama Steamship Co. adopted a resolution dated July 10, 1946 granting and setting aside, out of the proceeds expected to be collected on the insurance policies taken on the life of said Enrico Pirovano, the sum of P400,000.00 for equal division among the four (4) minor children of the deceased, said sum of money to be convertible into 4,000 shares of stock of the Company, at par, or 1,000 shares for each child. Shortly thereafter, the Company received the total sum of P643,000.00 as proceeds of the said life insurance policies obtained from American insurers. Upon receipt of the last stated sum of money, the Board of Directors of the Company modified, on January 6, 1947, the above- mentioned resolution by renouncing all its rights, title, and interest to the said amount of P643,000.00 in favor of the minor children of the deceased, subject to the express condition that said amount should be retained by the Company in the nature of a loan to it, drawing interest at the rate of five per centum (5%) per annum, and payable to the Pirovano children after the Company shall have first settled in full the balance of its present remaining bonded indebtedness in the sum of approximately P5,000,000.00. This latter resolution was carried out in a Memorandum Agreement on January 10, 1947 and June 17, 1947, respectively, executed by the Company and Mrs. Estefania R. Pirovano, the latter acting in her capacity as guardian of her children (petitioners-appellants herein) and pursuant to an express authority granted her by the court. On June 24, 1947, the Board of Directors of the Company further modified the last mentioned resolution providing therein that the Company shall pay the proceeds of said life insurance policies to the heirs of the said Enrico Pirovano after the Company shall have settled in full the balance of its present remaining bonded indebtedness, but the annual interests accruing on the principal shall be paid to the heirs of the said Enrico Pirovano, or their duly appointed representative, whenever the Company is in a position to meet said obligation. On February 26, 1948, Mrs. Estefania R. Pirovano, in behalf of her children, executed a public document formally accepting the donation; and, on the same date, the Company, through its Board of Directors, took official notice of this formal acceptance.

"In resum, we are of the opinion, that (1) the donor's gift tax in the sum of P34,371.76 was erroneously assessed and collected hence, petitioners are entitled to the refund thereof; (2) the donees' gift taxes were correctly assessed; (3) the imposition of the surcharge of 25% is not proper; (4) the surcharge of 5% is legally due and (5) the interest of 1 per cent per month on the deficiency donees' gift taxes is due from petitioners from March 8, 1955 until the taxes are paid. "IN LINE WITH FOREGOING OPINION, petitioners are hereby ordered to pay the donees' gift taxes as assessed by respondent, plus 5% surcharge and interest at the rate of 1% per month from March 8, 1955 to the date of payment of said donees' gift taxes. Respondent is ordered to apply the sum of P34,371.76 which is refundable to petitioners, against the amount due from petitioners. With cost against petitioners in Case No. 347." Petitioners-appellants herein filed a motion to reconsider the above decision which the lower court denied. Hence this appeal before us.

That the tax court regarded the conveyance as a simple donation, instead of a remuneratory one as it was declared to be in our previous decision, is but innocuous error; whether remuneratory or simple, the conveyance remained a gift, taxable under Chapter 2, Title III, of the Internal Revenue Code. But then, appellants contend, the entire property or right donated should not be considered as a gift for taxation purposes; only that portion of the value of the property or right transferred, if any, which is in excess of the value of the services rendered should be considered as a taxable gift. They cite in support Section III of the Tax Code which provides that "Where property is transferred for less than the adequate and full consideration in money or money's worth, then the amount by which the value of the property exceeded the value of the consideration shall, for the purpose of the tax imposed by this chapter, be deemed as a gift, . . . " The flaw in this argument lies in the fact that, as copied from American law, the term consideration used in this section refers to the technical "consideration" defined by the American Law Institute (Restatement of Contracts) as "anything that is bargained for by the promisor and given by the promise in exchange for the promise" (Also, v. Corbin on Contracts, vol. I, p. 359). But, as we have seen, Pirovano's successful activities as officer of the De la Rama Steamship Co. can not be deemed such consideration for the gift to his heirs, since the services were rendered long before the Company ceded the value of the life policies to said heirs; cession. services were not the result of one bargain or of a mutual exchange of promises. And the Anglo-American law treats a subsequent promise to pay for past services (like one to pay for improvements already made without prior request from the promisor) to be a Nudum pactum (Roscorla vs. Thomas, 3 O.B. 234; Peters vs. Poro, 25 ALR 615; Carson vs. Clark 25 Am. Dec. 79; Boston vs. Dodge, 12 Am. Dec. 205), i.e. one that is unenforceable in view of the common law rule that consideration must consist in a legal benefit to the promise or some legal detriment to the promisor. What is more, the actual consideration for the cession of the policies, as previously shown, was the Company's gratitude to Pirovano; so that under section III of the Tax Code there is no consideration the value of which can be deducted from that of the property transferred as a gift. Like "love and affection", gratitude has no economic value and is not "consideration" in the sense that the word is used in this section of the Tax Code. As stated by Chief Justice Griffith of the Supreme Court of Mississippi in his well-known book, "Outline of the Law' (p. 204) "Love and affection are not considerations of value they are not estimable in terms of value. Nor are sentiments of gratitude for gratuitous past favors or kindnesses; nor are obligations which are merely moral. It has been well said that if a moral obligation were alone sufficient it would remove the necessity for any consideration at all, since the fact of making a promise imposes the moral obligation to perform it." It is of course perfectly possible that a donation or gift should at the same time impose a burden or condition on the donee involving some economic liability for him. A, for example, may donate a parcel of land to B on condition that the latter assume a mortgage existing on the donated land. In this case the donee may rightfully insist that the gift tax be computed only on the value of the land less the value of the mortgage. This, in fact, is contemplated by Article 619 of the Civil Code of 1889 (Art. 726) of the New Code) when it provides that there is also a donation "when the gift imposes upon the donee a burden which is less than the value of the thing given". Section III of the Tax Code has in view situations of this kind, since it also prescribes that "the amount by which the value of the property exceeded the value of the consideration" shall be deemed a gift for the purpose of the tax. Petitioners finally contend that, even assuming that the donation in question is subject to donees' gift taxes, the imposition of the surcharge of 5% and interest of 1% per month from March 8, 1956 was not justified because the proceeds of the life insurance policies were actually received on April 6, 1955 and May 12,

In the instant appeal, petitioners-appellants herein question only that portion of the decision of the lower court ordering the payment of donees' gift taxes as assessed by respondent as well as the imposition of surcharge and interest on the amount of donees' gift taxes. In their brief and memorandum, they dispute the factual finding of the lower court that De la Rama Steamship Company's renunciation of its rights, title, and interest over the proceeds of said life insurance policies in favor of the Pirovano children "was motivated solely and exclusively by its sense of gratitude, an act of pure liberality, and not to pay additional compensation for services inadequately paid for". Petitioners now contend that the lower court's finding was erroneous in seemingly considering the disputed grant as a simple donation, since our previous decision (96 Phil. 335) had already declared that the transfer to the Pirovano children was a remuneration donation. Petitioners further contend that the same was not for an insufficient or inadequate consideration but rather it was made for a full and adequate compensation for the valuable services rendered by the late Enrico Pirovano to the De la Rama Steamship Co.; hence, the donation does not constitute a taxable gift under the provisions of Section 108 of the National Internal Revenue Code. The argument for petitioners-appellants fails to take into account the fact that neither in Spanish nor Anglo-American law was it considered that past services, rendered without relying on a coetaneous promise, express or implied, that such services would be paid for the future, constituted causa or consideration that would make a conveyance of property anything else but a gift or donation. This conclusion flows from the text of Article 619 of the Code of 1889 (identical with Article 726 of the present Civil Code of the Philippines): "When a person gives to another a thing . . . on account of the latter's merits or of the services rendered by him to the donor, provided they do not constitute a demandable debt, . . ., there is also a donation . . ." There is nothing on record to show that when the late Enrico Pirovano rendered services as President and General Manager of the De la Rama Steamship Co. he was not fully compensated for such services, or that, because they were "largely responsible for the rapid and very successful development of the activities of the company" (Resol. of July 10, 1946), Pirovano expected or was promised further compensation over and in addition to his regular emoluments as President and General Manager. The fact that his services contributed in a large measure to the success of the company did not give rise to a recoverable debt, and the conveyances made by the company to his heirs remain a gift or donation. This is emphasized by the director's Resolution of January 6, 1947, that "out of gratitude" the company decided to renounce in favor of Pirovano's heirs the proceeds of the life insurance policies in question. The true consideration for the donation was, therefore, the company's gratitude for his services, and not the services themselves.

1955 only and in accordance with Section 115(c) of the Tax Code; the filing of the returns of such tax became due on March 1, 1956 and the tax became payable on May 15, 1956, as provided for in Section 116(a) of the same Code. In other words, petitioners maintain that the assessment and demand for donees' gift taxes was prematurely made and of no legal effect; hence, they should not be held liable for such surcharge and interest. It is well to note, and it is not disputed, that petitioners donee have failed to file any gift tax return and that they also failed to pay the amount of the assessment made against them by respondent in 1955. This situation is covered by Section 119(b) (1) and (c) and Section 120 of the Tax Code. "(b)Deficiency. "(1)Payment not extended. Where a deficiency, or any interest assessed in connection therewith, or any addition to the taxes provided in section one hundred twenty is not paid in full within thirty days from the date of the notice and demand from the Collector, there shall be collected as a part of the taxes, interest upon the unpaid amount at the rate of one per centum a month from the date of such notice and demand until it is paid. (section 119) "(c)Surcharge. If any amount of the taxes included in the notice and demand from the Collector of Internal Revenue is not paid in full within thirty days after such notice and demand, there shall be collected in addition to the interest prescribed above as a part of the taxes a surcharge of five per centum of the unpaid amount." (sec. 119) The failure to file a return was found by the lower court to be due to reasonable cause and not to willful neglect. On this score, the elimination by the lower court of the 25% surcharge as ad valorem penalty which respondent Commissioner had imposed pursuant to Section 120 of the Tax Code was proper, since said Section 120 vests in the Commissioner of Internal Revenue or in the tax court power and authority to impose or not to impose such penalty depending upon whether or not reasonable cause has been shown in the nonfiling of such return. On the other hand, unlike said Section 120, Section 119, paragraphs (b) (1) and (c) of the Tax Code, does not confer on the Commissioner of Internal Revenue or on the courts any power and discretion not to impose such interest and surcharge. It is likewise provided for by law that an appeal to the Court of Tax Appeals from a decision of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue shall not suspend the payment or collection of the tax liability of the taxpayer unless a motion to that effect shall have been presented to the court and granted by it on the ground that such collection will jeopardize the interest of the taxpayer (Sec. 11, Republic Act No. 1125; Rule 12, Rules of the Court of Tax Appeals). It should further be noted that

secure a ruling as regards the validity of the tax before paying it would be to defeat this purpose." (National Dental Supply Co. vs. Meer 90 Phil. 265) Petitioners did not file in the lower court any motion for the suspension of payment or collection of the amount of assessment made against them. On the basis of the above stated provisions of law and applicable authorities, it is evident that the imposition of 1% interest monthly and 5% surcharge is justified and legal. As succinctly stated by the court below, said imposition is "mandatory and may not be waived by the Commissioner of Internal Revenue or by the courts" (Resolution on petitioners' motion for reconsideration, Annex XIV, petition). Hence, said imposition of interest and surcharge by the lower court should be upheld. WHEREFORE, the decision of the Court of Tax Appeals is affirmed. Costs against petitioners Pirovano.

E. Deductions from the Gross Estate COMMISIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE vs. COURT OF APPEALS G.R. No. 123206 March 22, 2000 Facts: Respondent heirs of Pedro Pajonar, executed extrajudicial settlement of the latters estate. Pursuant to the assessments of the BIR for deficiency tax, they paid the estate taxes. Later the administrator filed a protest seeking the refund of the erroneously paid estate taxes or some portion of it. Without the resolution of the protest, a petition for review was then filed with the CTA, which ordered the CIR to refund the heirs. Among the deductions from the gross estate allowed by the CTA were the amounts representing the Proceedings No. 1254 for guardianship over the person and property of the decedent while he was still alive. The CIR assailed the decision contending that the notarial fee for Extrajudicial Settlement and the attorneys fees in the guardianship proceedings are not deductible expenses. It maintains that only judicial expenses of the testamentary or intestate proceedings are allowed as deduction to gross estate. Issue: Are the notarial fee paid for the extrajudicial settlement and the attorneys fees in the guardianship proceedings allowed as deductions from the gross estate of the decedent in order to arrive at the value of the net estate? Held: Yes. Although the tax code specifies judicial expenses of the testamentary or intestate proceedings, there is no reason why expenses incurred in the administration and settlement of the estate in extrajudicial proceedings should not be allowed. However, deduction is limited to such administration expenses as are actually and necessarily incurred in the collection of the assets of the estate, payment of the debts, and distribution of the remainder among those entitled thereto. It is clear that the extrajudicial settlement was for the purpose of payment of taxes and the distribution of the estate to the heirs. The execution of the extrajudicial settlement necessitated the notarization of the same. It follows then that the notarial fee was incurred primarily to settle the estate of the deceased Pajonar. Said amount should then be considered as administration expense actually and necessarily incurred in the collection of assets of the estate, payment of debts and distribution of the remainder among those entitled thereto. Attorneys fees on the other hand to be deductible from the gross estate must be essential to the settlement of the estate. The amount claimed as deductible was incurred as attorneys fees in the guardianship proceedings. The guardianship proceeding in this case was necessary for the distribution of the property of the deceased. As correctly pointed out by the respondent CTA, the PNB was appointed guardian over the assets of the deceased, and that assets of the deceased form part of his gross estate.

"It has been the uniform holding of this Court that no suit for adjoining the collection of a tax, disputed or undisputed, can be brought, the remedy being to pay the tax first, formerly under protest and now without need of protest, file the claim with the Collector, and if he denies it, bring an action for recovery against him." (David vs. Ramos, et al., 90 Phil. 351) "Section 306 of the National Internal Revenue Code . . . lays down the procedure to be followed in those cases wherein a taxpayer entertains some doubt about the correctness of a tax sought to be collected. Said section provides that the tax should first be paid and the taxpayer should sue for its recovery afterwards. The purpose of the law obviously is to prevent delay in the collection of taxes upon which the Government depends for its existence. To allow a taxpayer to first

[G.R. No. 120880. June 5, 1997.] FERDINAND R. MARCOS II, petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS, THE COMMISSIONER OF THE BUREAU OF INTERNAL REVENUE and HERMINIA D. DE GUZMAN, respondents.

SYLLABUS 1.TAXATION; NATIONAL INTERNAL REVENUE CODE; ENFORCEMENT OF TAX LAWS AND COLLECTION OF TAXES, OF PARAMOUNT IMPORTANCE; CONFLICTING INTEREST OF AUTHORITIES AND TAXPAYERS MUST BE RECONCILED TO ACHIEVE REAL PURPOSE OF TAXATION. The enforcement of tax laws and the collection of taxes, is of paramount importance for the sustenance of government. Taxes are the lifeblood of the government and should be collected without unnecessary hindrance. However, such collection should be made in accordance with law as any arbitrariness will negate the very reason for government itself. It is, therefore, necessary to reconcile the apparently conflicting interests of the authorities and the taxpayers so that the real purpose of taxation, which is the promotion of the common good, may be achieved. IEAacT 2.REMEDIAL LAW; PROBATE COURT; JURISDICTION. The authority of the Regional Trial Court, sitting, albeit with limited jurisdiction, as a probate court over estate of deceased individual, is not a trifling thing. The court's jurisdiction, once invoked, and made effective, cannot be treated with indifference nor should it be ignored with impunity by the very parties invoking its authority. It is within the jurisdiction of the probate court to approve the sale of properties of a deceased person by his prospective heirs before final adjudication; to determine who are the heirs of the decedent; the recognition of a natural child; the status of a woman claiming to be the legal wife of the decedent; the legality of disinheritance of an heir by the testator; and to pass upon the validity of a waiver of hereditary rights. 3.TAXATION; NATIONAL INTERNAL REVENUE CODE; ESTATE TAX; NATURE OF PROCESS OF COLLECTION. The nature of the process of estate tax collection has been described as follows: "Strictly speaking, the assessment of a inheritance tax does not directly involve the administration of a decedent's estate, although it may be viewed as an incident to the complete settlement of an estate, and, under some statutes, it is made the duty of the probate court to make the amount of the inheritance tax a part of the final decree of distribution of the estate. It is not against the property of decedent, nor is it a claim against the estate as such, but it is against the interest or property right which the heir, legatee, devisee, etc., has in the property formerly held by decedent. Further, under some statutes, it has been held that it is not a suit or controversy between the parties, nor it is an adversary proceeding between the state and the person who owes the tax on the inheritance. However, under other statutes it has been held that the hearing and determination of the cash value of the assets and the determination of the tax are adversary proceedings. The proceeding has been held to be necessary a proceeding in rem. In the Philippine experience, the enforcement and collection of estate tax, is executive in character, as the legislature has seen it fit to ascribe this task to the Bureau of Internal Revenue. (Section 3 of the National Internal Revenue Code) ASICDH 4.ID.; ID.; ID.; LIBERAL TREATMENT OF CLAIMS. Thus, it was in Vera vs. Fernandez that the court recognized the liberal treatment of claims for taxes charged against the estate of the decedent. Such taxes, we said, were exempted from the application of the state of non-claims, and this is justified by the necessity of government funding, immortalized in the maxim that taxes are the lifeblood of the government. Vectigalia nervi sunt rei publicae taxes are the sinews of the state. Such liberal treatment of internal revenue taxes in the probate proceedings extends so far, even to allowing the enforcement of tax obligations against the heirs of the decedent, even after distribution of the estate's properties. 5.ID.; ID.; ID.; COLLECTION THEREOF DOES NOT REQUIRE APPROVAL OF PROBATE COURT. The approval of the court, sitting in

probate, or as a settlement tribunal over the deceased is not a mandatory requirement in the collection of estate taxes. It cannot therefore be argued that the Tax Bureau erred in proceeding with the levying and sale of the properties allegedly owned by the late President, on the ground that it was required to seek first the probate court's sanction. There is nothing in the Tax Code, and in the pertinent remedial laws that implies the necessity of the probate or estate settlement court's approval of the state's claim for estate taxes, before the same can be enforced and collected. On the contrary, under Section 87 of the NIRC, it is the probate or settlement court which is bidden not to authorize the executor or judicial administrator of the decedent's estate to deliver any distributive share to any party interested in the estate, unless it is shown a Certification by the Commissioner of Internal Revenue that the estate taxes have been paid. This provision disproves the petitioner's contention that it is the probate court which approves the assessment and collection of the estate tax. CSTcEI 6.ID.; ID.; DISTRAINT OR LEVY; REQUIRES FINAL, EXECUTORY AND DEMANDABLE DEFICIENCY TAX ASSESSMENT; CASE AT BAR. Apart from failing to file the required estate tax return within the time required for the filing of the same, petitioner, and the other heirs never questioned the assessments served upon them, allowing the same to lapse into finality, and prompting the BIR to collect the said taxes by levying upon the properties left by President Marcos. The Notices of Levy upon real properly were issued within the prescriptive period and in accordance with the provisions of the present Tax Code. The deficiency tax assessment, having already become final executory and demandable, the same can now be collected through the summary remedy for distraint or levy pursuant to Section 205 of the NIRC. 7.ID.; ID.; ESTATE TAX; 10-YEAR PRESCRIPTIVE PERIOD FOR ASSESSMENT AND COLLECTION OF TAX DEFICIENCY; CASE AT BAR. The applicable provision in regard to the prescriptive period for the assessment and collection of tax deficiency in this instance is Section 223 of the NIRC, which pertinently provides that the case of a false or fraudulent return with intent to evade tax or of a failure to file a return, the tax may be assessed, or a proceeding in court for the collection of such tax may be begun without assessment, at any time within ten (10) years after the discovery of the falsity, fraud, or omission. The omission to file an estate tax return, and the subsequent failure to contest or appeal the assessment made by the BIR is fatal to the petitioner's cause, as under the above-cited provision, in case of failure to file a return, the tax may be assessed at any time within ten years after the omission, and any tax so assessed may be collected by levy upon real properly within three years following the assessment of the tax. Since the estate tax assessment had become final and unappealable by the petitioner's default as regards protesting the validity of the said assessment, there is now no reason why the BIR cannot continue with the collection of the said tax. Any objection against the assessment should have been pursued following the avenue paved in Section 229 of the NIRC on protests on assessments of internal revenue taxes. 8.REMEDIAL LAW; EVIDENCE; PRESUMPTION THAT OFFICIAL DUTIES ARE REGULARLY PERFORMED; APPLIED IN CASE AT BAR. It is not the Department of Justice which is the government agency tasked to determine the amount of taxes due upon the subject estate, but the Bureau of Internal Revenue, whose determinations and assessments are presumed correct and made in good faith. The taxpayer has the duty of proving otherwise. In the absence of proof of any irregularities in the performance of official duties, an assessment will not be disturbed. Even an assessment based on estimates is prima facie valid and lawful where it does not appear to have been arrived at arbitrarily or capriciously. The burden of proof is upon the complaining party to show clearly that the assessment is erroneous. Failure to present proof of error in the assessment will justify the judicial affirmance of said assessment. In this instance, petitioner has not pointed out one single provision in the Memorandum of the Special Audit Team which gave rise to the questioned assessment, which bears a trace of falsity. Indeed the petitioner's attack on the assessment bears mainly on the alleged improbable and unconscionable amount of the taxes charged. But mere rhetoric cannot supply the basis for the charge of impropriety of the assessment made. cDACST 9.ID.; SPECIAL CIVIL ACTION; CERTIORARI; NOT A SUBSTITUTE FOR LOST APPEAL OF TAX ASSESSMENT. These objections to the assessments should have been raised, considering the ample remedies afforded the taxpayer by the Tax Code, with the Bureau of Internal Revenue and the Court of Tax Appeals, as described earlier, and cannot be raised now via Petition for Certiorari, under the pretext of grave abuse of discretion. The course of action taken by the petitioner reflects his disregard or even repugnance of the established institutions for governance in the scheme of a well-ordered society. The subject tax assessments having become final

executory and enforceable, the same can no longer be contested by means of a disguised protest. In the main, Certiorari may not be used as a substitute for a lost appeal or remedy. This judicial policy becomes more pronounced in view of the absence of sufficient attack against the actuations of government. 10.TAXATION; NATIONAL INTERNAL REVENUE CODE; DISTRAINT OR LEVY; ESTATE OF THE DECEDENT, NOT THE HEIRS, IS THE DELINQUENT TAXPAYER; NOTICES TO HEIRS, NOT REQUIRED BY LAW. In the case of notices of levy issued to satisfy the delinquent estate tax the delinquent taxpayer is the Estate of the decedent, and not necessarily, and exclusively, the petitioner as heir of the deceased. In the same vein, in the matter of income tax delinquency of the late president and his spouse, petitioner is not the taxpayer liable. Thus, it follows that service of notices of levy in satisfaction of these tax delinquencies upon the petitioner is not required by law, as under Section 213 of the NIRC.

actuation of the respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue in assessing, and collecting through the summary remedy of Levy on Real Properties, estate and income tax delinquencies upon the estate and properties of his father, despite the pendency of the proceedings on probate of the will of the late president, which is docketed as Sp. Proc. No. 10279 in the Regional Trial Court of Pasig, Branch 156. Petitioner had filed with the respondent Court of Appeals a Petition for Certiorari and Prohibition with an application for writ of preliminary injunction and/or temporary restraining order on June 28, 1993, seeking to I.Annul and set aside the Notices of Levy on real property dated February 22, 1993 and May 20, 1993, issued by respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue; II.Annul and set aside the Notices of Sale dated May 26, 1993;

11.CONSTITUTIONAL LAW; BILL OF RIGHTS; DUE PROCESS; NOT DENIED WHERE PARTY WAS DULY NOTIFIED BUT DISREGARDED OPPORTUNITY TO RAISE OBJECTIONS ON TAX ASSESSMENT. The record shows that notices of warrants of distraint and levy of sale were furnished the counsel of petitioner on April 7, 1993, and June 10 1993, and the petitioner himself on April 12, 1993 at his office at the Batasang Pambansa. We cannot, therefore, countenance petitioner's insistence that he was denied due process. Where there was an opportunity to raise objections to government action, and such opportunity was disregarded, for no justifiable reason, the party claiming oppression then becomes the oppressor of the orderly functions of government. He who comes to court must come with clean hands. Otherwise, he not only taints his name, but ridicules the very structure of established authority. TIDHCc

III.Enjoin the Head Revenue Executive Assistant Director II (Collection Service), from proceeding with the Auction of the real properties covered by Notices of Sale. After the parties had pleaded their case, the Court of Appeals rendered its Decision 2 on November 29, 1994, ruling that the deficiency assessments for estate and income tax made upon the petitioner and the estate of the deceased President Marcos have already become final and unappealable, and may thus be enforced by the summary remedy of levying upon the properties of the late President, as was done by the respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue. "WHEREFORE, premises considered judgment is hereby rendered DISMISSING the petition for Certiorari with prayer for Restraining Order and Injunction. No pronouncements as to cost. SO ORDERED." Unperturbed, petitioner is now before us assailing the validity of the appellate court's decision, assigning the following as errors: A.RESPONDENT COURT MANIFESTLY ERRED IN RULING THAT THE SUMMARY TAX REMEDIES RESORTED TO BY THE GOVERNMENT ARE NOT AFFECTED AND PRECLUDED BY THE PENDENCY OF THE SPECIAL PROCEEDING FOR THE ALLOWANCE OF THE LATE PRESIDENT'S ALLEGED WILL. TO THE CONTRARY, THIS PROBATE PROCEEDING PRECISELY PLACED ALL PROPERTIES WHICH FORM PART OF THE LATE PRESIDENT'S ESTATE IN CUSTODIA LEGIS OF THE PROBATE COURT TO THE EXCLUSION OF ALL OTHER COURTS AND ADMINISTRATIVE AGENCIES. B.RESPONDENT COURT ARBITRARILY ERRED IN SWEEPINGLY DECIDING THAT SINCE THE TAX ASSESSMENTS OF PETITIONER AND HIS PARENTS HAD ALREADY BECOME FINAL AND UNAPPEALABLE, THERE WAS NO NEED TO GO INTO THE MERITS OF THE GROUNDS CITED IN THE PETITION. INDEPENDENT OF WHETHER THE TAX ASSESSMENTS HAD ALREADY BECOME FINAL, HOWEVER, PETITIONER HAS THE RIGHT TO QUESTION THE UNLAWFUL MANNER AND METHOD IN WHICH TAX COLLECTION IS SOUGHT TO BE ENFORCED BY RESPONDENTS COMMISSIONER AND DE GUZMAN. THUS, RESPONDENT COURT

DECISION

TORRES, JR., J p: In this Petition for Review on Certiorari, Government action is once again assailed as precipitate and unfair, suffering the basic and oftly implored requisites of due process of law. Specifically, the petition assails the Decision 1 of the Court of Appeals dated November 29, 1994 in CA-G.R. SP No. 31363, where the said court held: "In view of all the foregoing, we rule that the deficiency income tax assessments and estate tax assessment, are already final and (u)nappealable and the subsequent levy of real properties is a tax remedy resorted to by the government, sanctioned by Section 213 and 218 of the National Internal Revenue Code. This summary tax remedy is distinct and separate from the other tax remedies (such as Judicial Civil actions and Criminal actions), and is not affected or precluded by the pendency of any other tax remedies instituted by the government. WHEREFORE, premises considered, judgment is hereby rendered DISMISSING the petition for certiorari with prayer for Restraining Order and Injunction. No pronouncements as to costs. SO ORDERED." More than seven years since the demise of the later Ferdinand E. Marcos, the former President of the Republic of the Philippines, the matter of the settlement of his estate, and its dues to the government in estate taxes, are still unresolved, the latter issue being now before this Court for resolution. Specifically, petitioner Ferdinand R. Marcos II, the eldest son of the decedent, questions the

SHOULD HAVE FAVORABLY CONSIDERED THE MERITS OF THE FOLLOWING GROUNDS IN THE PETITION: (1)The Notices of Levy on Real Property were issued beyond the period provided in the Revenue Memorandum Circular No. 38-68. (2)[a] The numerous pending court cases questioning the late President's ownership or interests in several properties (both personal and real) make the total value of his estate, and the consequent estate tax due, incapable of exact pecuniary determination at this time. Thus, respondents' assessment of the estate tax and their issuance of the Notices of Levy and Sale are premature, confiscatory and oppressive. [b]Petitioner, as one of the late President's compulsory heirs, was never notified, much less served with copies of the Notices of Levy, contrary to the mandate of Section 213 of the NIRC. As such, petitioner was never given an opportunity to contest the Notices in violation of his right to due process of law. C.ON ACCOUNT OF THE CLEAR MERIT OF THE PETITION, RESPONDENT COURT MANIFESTLY ERRED IN RULING THAT IT HAD NO POWER TO GRANT INJUNCTIVE RELIEF TO PETITIONER. SECTION 219 OF THE NIRC NOTWITHSTANDING, COURTS POSSESS THE POWER TO ISSUE A WRIT OF PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION TO RESTRAIN RESPONDENTS COMMISSIONER'S AND DE GUZMAN'S ARBITRARY METHOD OF COLLECTING THE ALLEGED DEFICIENCY ESTATE AND INCOME TAXES BY MEANS OF LEVY. The facts as found by the appellate court are undisputed, and are hereby adopted: "On September 29, 1989, former President Ferdinand Marcos died in Honolulu, Hawaii, USA. On June 27, 1990, a Special Tax Audit Team was created to conduct investigations and examinations of the tax liabilities and obligations of the late president, as well as that of his family, associates and "cronies". Said audit team concluded its investigation with a Memorandum dated July 26, 1991. The investigation disclosed that the Marcoses failed to file a written notice of the death of the decedent, an estate tax returns [sic], as well as several income tax returns covering the years 1982 to 1986, all in violation of the National Internal Revenue Code (NIRC). Subsequently, criminal charges were filed against Mrs. Imelda R. Marcos before the Regional Trial of Quezon City for violations of Sections 82, 83 and 84 (as penalized under Sections 253 and 254 in relation to Section 252-a & b) of the National Internal Revenue Code (NIRC). The Commissioner of Internal Revenue thereby caused the preparation and filing of the Estate Tax Return for the estate of the late president, the Income Tax Returns of the Spouses Marcos for the years 1985 to 1986, and the Income Tax Returns of petitioner

Ferdinand 'Bongbong' Marcos II for the years 1982 to 1985. On July 26, 1991, the BIR issued the following: (1) Deficiency estate tax assessment no. FAC-2-89-91002464 (against the estate of the late president Ferdinand Marcos in the amount of P23,293,607,638.00 Pesos); (2) Deficiency income tax assessment no. FAC-1-85-91-002452 and Deficiency income tax assessment no. FAC-1-86-91-002451 (against the Spouses Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos in the amounts of P149,551.70 and P184,009,737.40 representing deficiency income tax for the years 1985 and 1986); (3) Deficiency income tax assessment nos. FAC-1-82-91-002460 to FAC-1-85-91-002463 (against petitioner Ferdinand 'Bongbong' Marcos II in the amounts of P258.70 pesos; P9,386.40 Pesos; P4,388.30 Pesos; and P6,376.60 Pesos representing his deficiency income taxes for the years 1982 to 1985). The Commissioner of Internal Revenue avers that copies of the deficiency estate and income tax assessments were all personally and constructively served on August 26, 1991 and September 12, 1991 upon Mrs. Imelda Marcos (through her caretaker Mr. Martinez) at her last known address at No. 204 Ortega St., San Juan, M.M. (Annexes 'D' and 'E' of the Petition). Likewise, copies of the deficiency tax assessments issued against petitioner Ferdinand 'Bongbong' Marcos II were also personally and constructively served upon him (through his caretaker) on September 12, 1991, at his last known address at Don Mariano Marcos St. corner P. Guevarra St., San Juan, M.M. (Annexes 'J' and 'J-1' of the Petition). Thereafter, Formal Assessment notices were served on October 20, 1992, upon Mrs. Marcos c/o petitioner, at his office, House of Representatives, Batasan Pambansa, Quezon City. Moreover, a notice to Taxpayer inviting Mrs. Marcos (or her duly authorized representative to counsel), to a conference, was furnished the counsel of Mrs. Marcos, Dean Antonio Coronel but to no avail. The deficiency tax assessments were not protested administratively, by Mrs. Marcos and the other heirs of the late president, within 30 days from service of said assessments. On February 22, 1993, the BIR Commissioner issued twenty-two notices of levy on real property against certain parcels of land owned by the Marcoses to satisfy the alleged estate tax and deficiency income taxes of Spouses Marcos.

On May 20, 1993, four more Notices of Levy on real property were issued for the purpose of satisfying the deficiency income taxes. On May 26, 1993, additional four (4) notices of Levy on real property were again issued. The foregoing tax remedies were resorted to pursuant to Sections 205 and 213 of the National Internal Revenue Code (NIRC). In response to a letter dated March 12, 1993 sent by Atty. Loreto Ata (counsel of herein petitioner) calling the attention of the BIR and requesting that they be duly notified of any action taken by the BIR affecting the interest of their client Ferdinand 'Bongbong' Marcos II, as well as the interest of the late president copies of the aforesaid notices were served on

April 7, 1993 and on June 10, 1993, upon Mrs. Imelda Marcos, the petitioner, and their counsel of record, 'De Borja, Medialdea, Ata, Bello, Guevarra and Serapio Law Office'. Notices of sale at public auction were posted on May 26, 1993, at the lobby of the City Hall of Tacloban City. The public auction for the sale of the eleven (11) parcels of land took place on July 5, 1993. There being no bidder, the lots were declared forfeited in favor of the government. On June 25, 1993, petitioner Ferdinand 'Bongbong' Marcos II filed the instant petition for certiorari and prohibition under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court, with prayer for temporary restraining order and/or writ of preliminary injunction." It has been repeatedly observed, and not without merit, that the enforcement of tax laws and the collection of taxes, is of paramount importance for the sustenance of government. Taxes are the lifeblood of the government and should be collected without unnecessary hindrance. However, such collection should be made in accordance with law as any arbitrariness will negate the very reason for government itself. It is therefore necessary to reconcile the apparently conflicting interests of the authorities and the taxpayers so that the real purpose of taxation, which is the promotion of the common good, may be achieved. 3 Whether or not the proper avenues of assessment and collection of the said tax obligations were taken by the respondent Bureau is now the subject of the Court's inquiry. Petitioner posits that notices of levy, notices of sale, and subsequent sale of properties of the late President Marcos effected by the BIR are null and void for disregarding the established procedure for the enforcement of taxes due upon the estate of the deceased. The case of Domingo vs. Garlitos 4 is specifically cited to bolster the argument that "the ordinary procedure by which to settle claims of indebtedness against the estate of a deceased, person, as in an inheritance (estate) tax, is for the claimant to present a claim before the probate court so that said court may order the administrator to pay the amount therefor." This remedy is allegedly, exclusive, and cannot be effected through any other means. Petitioner goes further, submitting that the probate court is not precluded from denying a request by the government for the immediate payment of taxes, and should order the payment of the same only within the period fixed by the probate court for the payment of all the debts of the decedent. In this regard, petitioner cites the case of Collector of Internal Revenue vs. The Administratrix of the Estate of Echarri (67 Phil 502), where it was held that: "The case of Pineda vs. Court of First Instance of Tayabas and Collector of Internal Revenue (52 Phil 803), relied upon by the petitioner-appellant is good authority on the proposition that the court having control over the administration proceedings has jurisdiction to entertain the claim presented by the government for taxes due and to order the administrator to pay the tax should it find that the assessment was proper, and that the tax was legal, due and collectible. And the rule laid down in that case must be understood in relation to the case of Collector of Customs vs. Haygood, supra., as to the procedure to be followed in a given case by the government to effectuate the collection of the tax. Categorically stated, where during the pendency of judicial administration over the estate of a deceased person a claim for taxes is presented by the government, the court has the authority to order payment by the administrator; but, in the same way that it has authority to order payment or satisfaction, it also has the negative authority to deny the same. While there are cases where courts are required to perform certain duties mandatory and ministerial in character, the function of the court in a case of the present character

is not one of them; and here, the court cannot be an organism endowed with latitude of judgment in one direction, and converted into a mere mechanical contrivance in another direction." On the other hand, it is argued by the BIR, that the state's authority to collect internal revenue taxes is paramount. Thus, the pendency of probate proceedings over the estate of the deceased does not preclude the assessment and collection, through summary remedies, of estate taxes over the same. According to the respondent, claims for payment of estate and income taxes due and assessed after the death of the decedent need not be presented in the form of a claim against the estate. These can and should be paid immediately. The probate court is not the government agency to decide whether an estate is liable for payment of estate of income taxes. Well-settled is the rule that the probate court is a court with special and limited jurisdiction. Concededly, the authority of the Regional Trial Court, sitting, albeit with limited jurisdiction, as a probate court over estate of deceased individual, is not a trifling thing. The court's jurisdiction, once invoked, and made effective, cannot be treated with indifference nor should it be ignored with impunity by the very parties invoking its authority. In testament to this, it has been held that it is within the jurisdiction of the probate court to approved (sic) the sale of properties of a deceased person by his prospective heirs before final adjudication; 5 to determine who are the heirs of the decedent; 6 the recognition of a natural child; 7 the status of a woman claiming to be the legal wife of the decedent; 8 the legality of disinheritance of an heir by the testator; 9 and to pass upon the validity of a waiver of hereditary rights. 10 The pivotal question the court is tasked to resolve refers to the authority of the Bureau of Internal Revenue to collect by the summary remedy of levying upon, and sale of real properties of the decedent, estate tax deficiencies, without the cognition and authority of the court sitting in probate over the supposed will of the deceased. The nature of the process of estate tax collection has been described as follows: "Strictly speaking, the assessment of an inheritance tax does not directly involve the administration of a decedent's estate, although it may be viewed as an incident to the complete settlement of an estate, and, under some statutes, it is made the duty of the probate court to make the amount of the inheritance tax a part of the final decree of distribution of the estate. It is not against the property of decedent, nor is it a claim against the estate as such, but it is against the interest or property right which the heir, legatee, devisee, etc., has in the property formerly held by decedent. Further, under some statutes, it has been held that it is not a suit or controversy between the parties, nor is it an adversary proceeding between the state and the person who owes the tax on the inheritance. However, under other statutes it has been held that the hearing and determination of the cash value of the assets and the determination of the tax are adversary proceedings. The proceeding has been held to be necessarily a proceeding in rem." 11 In the Philippine experience, the enforcement and collection of estate tax, is executive in character, as the legislature has seen it fit to ascribe this task to the Bureau of Internal Revenue. Section 3 of the National Internal Revenue Code attests to this: "Sec. 3.Powers and duties of the Bureau. The powers and duties of the Bureau of Internal Revenue shall comprehend the assessment and collection of all national internal revenue taxes, fees, and charges, and the enforcement of all forfeitures, penalties, and fines connected therewith, including the execution of judgments in all cases decided in its favor by the Court of Tax Appeals and the ordinary courts. Said Bureau shall also give effect to and administer the

supervisory and police power conferred to it by this Code or other laws." Thus, it was in Vera vs. Fernandez 12 that the court recognized the liberal treatment of claims for taxes charged against the estate of the decedent. Such taxes, we said, were exempted from the application of the statute of non-claims, and this is justified by the necessity of government funding, immortalized in the maxim that taxes are the lifeblood of the government. Vectigalia nervi sunt rei publicae taxes are the sinews of the state. "Taxes assessed against the estate of a deceased person, after administration is opened, need not be submitted to the committee on claims in the ordinary course of administration. In the exercise of its control over the administrator, the court may direct the payment of such taxes upon motion showing that the taxes have been assessed against the estate." Such liberal treatment of internal revenue taxes in the probate proceedings extends so far, even to allowing the enforcement of tax obligations against the heirs of the decedent, even after distribution of the estate's properties. "Claims for taxes, whether assessed before or after the death of the deceased, can be collected from the heirs even after the distribution of the properties of the decedent. They are exempted from the application of the statute of non-claims. The heirs shall be liable therefor, in proportion to their share in the inheritance." 13

his findings. Within a period to be prescribed by implementing regulations, the taxpayer shall be required to respond to said notice. If the taxpayer fails to respond, the Commissioner shall issue an assessment based on his findings. Such assessment may be protested administratively by filing a request for reconsideration or reinvestigation in such form and manner as may be prescribed by implementing regulations within (30) days from receipt of the assessment; otherwise, the assessment shall become final and unappealable. If the protest is denied in whole or in part, the individual, association or corporation adversely affected by the decision on the protest may appeal to the Court of Tax Appeals within thirty (30) days from receipt of said decision; otherwise, the decision shall become final, executory and demandable. (As inserted by P.D. 1773)" Apart from failing to file the required estate tax return within the time required for the filing of the same, petitioner, and the other heirs never questioned the assessments served upon them, allowing the same to lapse into finality, and prompting the BIR to collect the said taxes by levying upon the properties left by President Marcos. Petitioner submits, however, that "while the assessment of taxes may have been validly undertaken by the Government, collection thereof may have been done in violation of the law. Thus, the manner and method in which the latter is enforced may be questioned separately, and irrespective of the finality of the former, because the Government does not have the unbridled discretion to enforce collection without regard to the clear provision of law." 14 Petitioner specifically points out that applying Memorandum Circular No. 3868, implementing Sections 318 and 324 of the old tax code (Republic Act 5203), the BIR's Notices of Levy on the Marcos properties, were issued beyond the allowed period, and are therefore null and void: ". . . the Notices of Levy on Real Property (Annexes O to NN of Annex C of this Petition) in satisfaction of said assessments were still issued by respondents well beyond the period mandated in Revenue Memorandum Circular No. 38-68. These Notices of Levy were issued on 22 February 1993 and 20 May 1993 when at least seventeen (17) months had already lapsed from the last service of tax assessment on 12 September 1991. As no notices of distraint of personal property were first issued by respondents, the latter should have complied with Revenue Memorandum Circular No. 38-68 and issued these Notices of Levy not earlier than three (3) months nor later than six (6) months from 12 September 1991. In accordance with the Circular, respondents only had until 12 March 1992 (the last day of the sixth month) within which to issue these Notices of Levy. The Notices of Levy, having been issued beyond the period allowed by law, are thus void and of no effect." 15 We hold otherwise. The Notices of Levy upon real property were issued within the prescriptive period and in accordance with the provisions of the present Tax Code. The deficiency tax assessment, having already become final, executory, and demandable, the same can now be collected through the summary remedy of distraint or levy pursuant to Section 205 of the NIRC. The applicable provision in regard to the prescriptive period for the assessment and collection of tax deficiency in this instance is Section 223 of the NIRC, which pertinently provides: "Sec. 223.Exceptions as to a period of limitation of assessment and collection of taxes. (a) In the case of a false or fraudulent return with intent to evade tax or of a failure to file a return, the tax may be assessed,

"Thus, the Government has two ways of collecting the taxes in question. One, by going after all the heirs and collecting from each one of them the amount of the tax proportionate to the inheritance received. Another remedy, pursuant to the lien created by Section 315 of the Tax Code upon all property and rights to property belong to the taxpayer for unpaid income tax, is by subjecting said property of the estate which is in the hands of an heir or transferee to the payment of the tax due the estate. (Commissioner of Internal Revenue vs. Pineda, 21 SCRA 105, September 15, 1967.) From the foregoing, it is discernible that the approval of the court, sitting in probate, or as a settlement tribunal over the deceased is not a mandatory requirement in the collection of estate taxes. It cannot therefore be argued that the Tax Bureau erred in proceeding with the levying and sale of the properties allegedly owned by the late President, on the ground that it was required to seek first the probate court's sanction. There is nothing in the Tax Code, and in the pertinent remedial laws that implies the necessity of the probate or estate settlement court's approval of the state's claim for estate taxes, before the same can be enforced and collected. On the contrary, under Section 87 of the NIRC, it is the probate or settlement court which is bidden not to authorize the executor or judicial administrator of the decedent's estate to deliver any distributive share to any party interested in the estate, unless it is shown a Certification by the Commissioner of Internal Revenue that the estate taxes have been paid. This provision disproves the petitioner's contention that it is the probate court which approves the assessment and collection of the estate tax. If there is any issue as to the validity of the BIR's decision to assess the estate taxes, this should have been pursued through the proper administrative and judicial avenues provided for by law. Section 229 of the NIRC tells us how: "Sec. 229.Protesting of assessment. When the Commissioner of Internal Revenue or his duly authorized representative finds that proper taxes should be assessed, he shall first notify the taxpayer of