Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Abject Sexuality in Pop Art

Uploaded by

Gris ArvelaezOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Abject Sexuality in Pop Art

Uploaded by

Gris ArvelaezCopyright:

Available Formats

ABJECT

SEXUALITY

IN

POP

ART

Joe

A.

Thomas

Erotic

art

has

long

comprised

the

secret

museum

of

art

history

because

societal

taboos

and

restrictive

cultural

mors

have

created

an

awkward

and

embarrassing

atmosphere

around

human

sexuality,

at

least

in

the

west.

Similarly,

some

writers

and

viewers

have

considered

Pop

Art

as

something

of

an

embarrassment

in

the

history

of

art.

Seen

as

selling

out

modernism,

its

popular

and

economic

success

helped

to

spur

its

general

critical

rejection

in

the

art

world

of

the

early

sixties.

Pop

was

seen

as

thumbing

its

nose

at

serious

modernist

art

for

many

reasons,

but

among

the

least

discussed

of

its

artistic

transgressions

has

been

the

consistent

use

of

sexual

and

erotic

imagery.

In

a

sort

of

artistic

patricide,

the

Pop

artists

used

erotic

images

as

part

of

an

overall

strategy

to

establish

themselves

as

the

new

avant-garde

while

distancing

themselves

from

the

oppressive

weight

of

the

Abstract

Expressionist

art

establishment.

In

1939

Clement

Greenbergs

Avant-Garde

and

Kitsch

codified

the

almost

sacred

separation

of

modernist,

highbrow

culture

and

art

from

popular,

lowbrow

products.

In

Greenbergs

view

whatever

held

popular

appeal

for

the

masses

was

by

definition

lowbrow

kitsch

and

artistically

insignificant.

Kitsch

was

thus

defined

by

its

designated

site

in

popular

culture.

Greenberg

was

not

alone

in

his

opposition

to

mass

culture;

commercial

art

and

popular

media

were

widely

considered

artistically

insignificant.

Bernard

Rosenberg

and

David

Manning

White,

discussing

mass

culture

in

1957,

expressed

the

accepted

opinion

that

art

was

the

counterconcept

to

popular

culture

and

that

a

genuine

esthetic

(or

religious

or

love)

experience

becomes

difficult,

if

not

impossible,

whenever

kitsch

pervades

the

atmosphere.1 When

Pop

artists

began

to

appropriate

popular

culture

by

using

commercial

images

and

styles,

they

defied

Greenbergs

artistic

hierarchies

and

consciously

sought

out

the

abjectrelative

to

their

own

art-historical

context.

While

some

recent

psychoanalytic

theory

projects

many

complex

layers

of

meaning

onto

the

term

abjection,

I

prefer

a

less

labored

definition.

Websters

dictionary

defines

abject

as

miserable;

wretched

or

lacking

self-respect;

degraded.

It

derives

from

the

Latin

verb

abjicere,

which

means

to

throw

away.

The

modernist

imperative

included

an

unspoken

rule

The

Free

Press,

1957),

10.

1 Bernard Rosenberg and David Manning White, eds., Mass Culture: The Popular Arts in America (London:

that

the

radicality

of

the

art

would

produce

an

underlying

sense

of

the

abject,

hence

provoking

negative

reactions

of

shock

from

an

uninformed

public.

Pop

Art,

however,

redoubled

and

redefined

the

modernist

affection

for

the

abject.

Even

the

self-styled

avant-garde

saw

it

as

miserable

and

wretched.

Max

Kozoloffs

famous

1962

article

derided

the

emerging

style

for

its

metaphysical

disgust

practiced

by

new

vulgarians.2

Paradoxically,

Pop

artists

had

turned

to

popular

culture

largely

because

they

felt

such

intense

pressure

to

conform

to

modernist

standards

of

the

avant-garde.

Andy

Warhol

well

illustrated

this

impulse.

As

he

began

to

seek

a

high

profile

in

the

New

York

art

world,

he

visited

the

art-lending

gallery

then

offered

by

the

Museum

of

Modern

Art.

Upon

seeing

a

collage

by

Rauschenberg,

Warhol

remarked

with

disgust,

Thats

a

piece

of

shit.

Anyone

can

do

that.

I

can

do

that.

His

friend

Ted

Carrey

responded,

Well,

why

dont

you

do

it?

Well,

Ive

got

to

think

of

something

different,

was

Warhols

response.3

The

Pop

artists

effectiveness

in

conveying

their

radical

status

was

instantaneous

and

profound.

Thomas

Hess

reported

that

a

leading

modernist

painter,

upon

seeing

the

watershed

exhibition

of

Pop

and

other

art

at

Sidney

Janis

Gallerys

New

Realists

show

in

November

1962,

exclaimed,

I

feel

a

bit

like

a

follower

of

Ingres

looking

at

the

first

Monets.4

In

fact,

the

disgust

of

the

modernist

establishment

was

such

that

Janiss

entire

stable

of

Abstract

Expressionists

(except

Willem

de

Kooning)

left

his

gallery.5

Erotic

and

sexual

contentwhich

could

increase

the

arts

wretched

and

degrading

connotationswere

among

the

Pop

artists

most

effective

tools

in

establishing

their

avant- garde

credentials.

All

of

the

major

Pop

artists

involved

themselves

with

such

imagery

to

some

degree,

particularly

those

whose

work

commented

on

the

mass

media

exploitation

of

female

sexuality:

Tom

Wesselmann

and

Mel

Ramos.

Typical

of

Wesselmanns

work

is

Great

American

2

Max

Kozloff,

Pop

Culture,

Metaphysical

Disgust,

and

the

New

Vulgarians,

Art

International

6

(March

1962):

34-36.

3

Patrick

Smith,

Art

in

Extremis:

Andy

Warhol

and

his

Art

(Ph.D.

diss.,

Northwestern

University,

1932),

468-69.

4

Thomas

Hess,

New

Realists,

Art

News

61

(December

1962):

12.

5

Barbara

Haskell,

Blam!

The

Explosion

of

Pop,

Minimalism,

and

Performance,

1958-1964

(New

York:

Whitney

Museum

of

American

Art

in

association

with

W.

W.

Norton

&

Co.,

1984),

86;

Calvin

Tomkins,

Profiles:

A

Good

Eye

and

a

Good

Ear,

Leo

Castelli,

The

New

Yorker,

26

May

1980,62.

Nude #55 of 1964. All of the elements of the painting are simplified into flat areas of commercial-looking, bright color, except for the tasteless, leopard-print spread on which the nude lies. The artists characteristic emphasis on erogenous zones by the use of contrasting colors is heightened in this work by the use of collaged hair. Interestingly, in explaining his artistic strategy the artist revealed an odd conflation of formalism with a realization of the abject quality of the subject. He stated (not referring specifically to #55) that he found the emphasized pubic areas blatantly erotic and consequently visually aggressive. A shaved vagina had the same vividness and immediacy as a strong red.6 Mel Ramoss most famous works are probably the paintings of 1965-66 in which nude centerfold girls were paired with common commercial products (usually food, but always something consumable). In Val Veeta a nubile sixties sex kitten sprawls on a giant box of Velveeta cheese spread. Ramos customarily played with the title in order to alliteratively connect the womans name with the corresponding product. The painting equates the highly processed and artificial erotic image of the nude woman with the similarly processed and

artificial

food

product.

The

sensual

aspects

of

the

food

parallel

the

sensual

aspects

of

the

nude.

The

extensive

finishing

and

processing

that

such

a

nude

model

would

undergoincluding

later

airbrushingmade

her

a

product

as

far

removed

from

a

real

woman

as

the

rubbery,

glutinous

Velveeta

is

from

real

cheese.

Both

were

meant

to

be

consumedone

by

the

eyes,

the

other

by

the

mouth.

Ramoss

smooth

brushwork

in

Val

Veeta

imitates

the

airbrushed

perfection

of

Playboy

centerfold

models

and

recalls

the

slick

technique

of

advertising

illustration.

Both

in

style

and

subject,

the

painting

embodies

some

of

the

most

reviled

and

abject

features

of

popular

culture:

blatant

consumerism,

the

sexual

sell,

crassness.

Oddly,

Ramos

has

never

acknowledged

any

such

purposeful

strategy,

however,

maintaining

that

he

is

just

a

figure

painter.7

In

contrast,

Claes

Oldenburg

explicitly

related

eroticism

to

the

transformative

nature

of

his

art.

As

he

said,

My

work

is

always

on

its

way

between

one

point

and

another.8

The

points

in

his

particular

artistic

geometry

usually

encompassed

mundane

objects

at

one

end

6

Slim

Stealingworth

[Tom

Wesselman],

Wesselmann

(New

York:

Abbeville,

1980),

23.

7

Mel

Ramos,

interview

by

the

author,

30

May

1991,

Oakland,

California,

Tape

recording.

8

Lawrence

Alloway,

American

Pop

Art

(New

York:

Macmillan,

1974),

101.

and

sexual

organs

or

erotic

symbols

at

the

other.

Falling

Shoestring

Potatoes

(1966)

illustrates

the

fluid

mutations

Oldenburg

saw

in

objects.

Ostensibly

it

is

a

giant

bag

of

French

fries

spilling

onto

the

gallery

floor.

But

as

Lawrence

Alloway

has

explained,

in

a

sketch

for

the

piece

Oldenburg

wrote

that

an

electrical

plug

equals

legs,

which

then

equal

shoestring

potatoes.

The

potatoes

resembled

both

legs

and

the

prongs

of

the

plug,

while

the

sack/skirt

from

which

the

potatoes/legs

protrude

was

the

plug

itself;

the

French

fries

were

thus

a

metaphor

for

legs

under

a

miniskirt

and

an

electrical

plug.9

Oldenburgs

vision

of

a

pansexual

world

correlated

with

contemporaneous

psychoanalytic

theories

that

posited

sexuality

as

being

at

the

root

of

our

perception.

Oldenburg

was

a

fan

of

Norman

O.

Brown,

an

early

sixties

writer

and

thinker

who

believed

in

the

renunciation

and

repression

of

logic

in

a

favor

of

a

return

to

the

polymorphous

perversity

of

infancy

as

described

by

Freud.10

There

is

often

a

grotesque

quality

to

Oldenburgs

transmutations:

for

example,

in

a

musing

written

in

his

notebooks,

ice

cream

=

God

=

sperm.11

Such

polymorphous

perversity

would

have

created

a

sense

of

abjection

in

a

typical

squeamish

1960s

viewer.

Almost

as

soon

as

James

Rosenquist

turned

to

painting

Pop

works,

erotic

elements

began

to

appear.

I

Love

You

With

My

Ford

has

probably

received

more

critical

attention

than

any

other

Rosenquist

painting

except

F-111.

Gene

Swenson

wrote

in

1962:

The

upper

section,

an

obsolescent

49

Ford,

comments

on

things

which

change

(car

models),

or

persist

(making

love

in

cars).

The

progressive

enlargement

of

scale

in

the

three

sections

parallels

the

increasing

loss

of

identity

in

the

sexual

act.12

Or

as

Simon

Wilson

saw

it,

.

.

.

the

Ford

phallic

symbol

looms

over

the

face

of

the

girl,

her

eyes

closed

and

lips

parted

in

ecstasy,

while

below

the

consummation

is

somehow

symbolized

by

the

writhing,

glutinous

masses

of

spaghetti.13

9

Ibid.,

104.

10

Barbara

Rose,

The

Origins,

Life

and

times

of

Ray

Gun,

Artforum

8

(November

1969):

57;

Barbara

Rose,

Claes

Oldenburg

(New

York:

Museum

of

Modern

Art,

1970),

64.

11Ellen

Johnson,

Claes

Oldenburg

(Harmondsworth

and

Baltimore:

Penguin,

1971),

24.

12

Gene

Swenson,

The

New

American

Sign

Painters,

Art

News

61

(September

1962):

60-61.

13

Simon

Wilson,

Pop

(Woodbury,

NY:

Barrrons,

1978),

24.

Rosenquists title perhaps suggests that commodity exchange involving objects such as this

will replace physical affection (and its accompanying messiness and complications). The artist depicted the sexual act on three levels corresponding to the three horizontal bands of imagery. On top is the car itself, a representation of consumerist societys love affair with the automobile. The middle register conveys the romance of the sexual act as immortalized in films and advertisements: the idealized embrace of a white, heterosexual couple, reduced to the acceptable synecdoche of faces pressed together. In the lowest register, the spaghetti refers to the actual, sensual, physical experience of sexual intercourse. The symbolic consummation of the spaghetti refers to the most abject attributes of the sexual act: the friction of mucous membranes and the secretion of bodily fluids. The softly modulated contours of Rosenquists billboard-inspired brushwork increase the sensuality of the spaghetti and the embracing couple above it. As with Oldenburgs work, there is a grotesque aspect to Rosenquists metaphorical conjunction of the most base and physical aspects of love with American commercialism. Andy Warhol went far beyond the teasing, often subliminal sexuality of advertising and mass media by dealing with sex more candidly than any other Pop artist. Among Warhols earliest, widely-noticed works were silkscreened images of Hollywood sex symbols such as Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor. However, the very first of these images, made in limited numbers during the summer of 1962, depicted the male actors Troy Donahue and Warren Beatty. Thomas Crow has demeaned these works as dead-end experiments,14 but their erotic content is significant. While the open recognition of male sex symbols was largely taboo in normative straight culture, Donahue and Beatty would have been widely and openly renowned as desirable sexual objects by Warhol and others in New Yorks gay subculture. As Warhol told an interviewer regarding Donahue, He was so great. God!15 In 1963 Warhol first announced his intention to make pornographic pictures using black lights so that the canvas looked blank under normal gallery lights. If the show was

14

Thomas

Crow,

Saturday

Disasters:

trace

and

Reference

in

Early

Warhol,

Art

in

America

75

(May

1987):

134.

15

Smith,

944.

raided by the police, the lights would go on and the evidence would disappear.16 Such a painting finally appeared in October 1966 at Sidney Janis Gallerys Erotic Art 66 show.17 Seemingly derived from a soft-core pornographic nude, in his usual serial fashion Warhol repeated the image of a womans stomach and breasts. Art critic David Bourdon recalled that the image was repeated on many panels that covered a wall, and that a special switch was available for the viewer to turn on the ultraviolet light,18 just as Warhol had earlier planned. Interestingly, the eerie glow of the ultraviolet light in the darkness and the flicking off of the lights before the show starts is also reminiscent of the peep shows and porno arcades of 42nd Street, with which Warhol was certainly familiar. Warhols forays into filmmaking were startlingly sexual almost from the beginning. In

fact,

we

might

even

say

that

Warhols

entire

film

career

was

predicated

on

sexuality.

The

first

film

for

which

he

became

widely

known,

Sleep,

depicted

Warhols

then-crush,

the

poet

John

Giorno,

sleeping

for

hours,

variously

repeated

into

a

six-hour

film.

The

reels

focused

on

Giornos

nude

body

and

created

a

teasing

nudity

and

subtle

eroticism.

Only

a

few

months

later

in

January

1964

Warhol

filmed

another,

more

explicitly

sexual

work,

Blow

Job.

The

camera

never

left

the

face

of

the

still-anonymous

Factory

visitor

who

was

the

films

focus;

it

simply

documents

the

varied

and

sometimes

hilarious

expressions

that

passed

across

his

face.

If

not

for

the

title

the

nature

of

the

activity

would

be

difficult

to

determine.

Such

films,

which

engaged

eroticism

through

allusion,

were

a

far

cry

from

slightly

later

works

such

as

Couch,

explicitly

depicting

random

couplings

on

a

couch

in

the

silver

Factory.

With

connotations

ranging

from

pornography

to

homosexuality,

the

sexuality

of

Warhols

oeuvre

was

probably

the

most

threatening

of

any

Pop

artist

to

the

sixties

establishment.

Pops

obvious

connections

to

quickly

shifting

trends

in

mass

culture

often

resulted

in

the

two

being

directly

confused

with

each

other.

Max

Kozloff

reported

in

1965

that

media

had

started

to

connect

art

with

other

aspects

of

popular

culture

because

of

a

confusion

between

behavior

at

openings

(or

at

independent

film

showings

or

discotheques)

and

works

of

art.19

16

Gene

Swenson,

What

is

Pop

Art?

Part

I,

Art

News

62

(November

1963):

60-61.

17

New

York,

Sidney

Janis

Gallery,

Erotic

Art

66,

Exhibition

3-29

October

1966.

18 David Bourdon, interview by author, Tape recording, New York, 15 May 1991. 19 Max Kozloff, Art: Review of the Season, The Nation, 7 June 1965, 623.

Gallery receptions could be news for the society page. Art became fashionable and hip in a way it had not been before. Pop Art rapidly became connected in the public mind to a variety of simultaneous cultural trends. For instance, the art world and the public often associated Pop with the burgeoning interest in the camp sensibility, exemplified by the publication of Susan Sontags Notes on Camp in late 1964.20 The conflation of the two even resulted in a wave of accusations that Pop Art was a homosexual conspiracy to ruin the art world.21 Warhols importance in this phenomenon cannot be underestimated. Although he was the last of the major New York Pop artists to have a solo exhibition, he quickly became the most famous of the group because of his purposely outrageous lifestyle and his clever manipulation of media. Starting as a commercial artist, then moving to paintings, films, nightclubs, bands, and becoming a semi-professional party-goer, Warhol both epitomized and spearheaded the blending of genres at the time. His undisguised homosexuality added a good deal of verve to his public image as a shocking sexual rebel. His retinue of pill-popping drag queens, gays, lesbians, and others of varied sexual orientations completed the outrageous picture he sought to portray. By promoting a bandthe Velvet Undergroundopening a nightclubThe Exploding Plastic Inevitableand attending (often crashing) society gatherings, he associated Pop Art with everything trendy and fashionable. Sexuality involves an element of pleasure just as popular culture does, and the pleasurable aspects of Pop also played an important role in both its initial critical rejection and its association with the abject. Dick Hebdige pointed out that critics summarily dismissed Pop Art as empty and shallow, but that Pop actually set out to blur the distinctions and overturn the suppositions that provided the very foundations of this critical attitude. By way of explanation Hebdige quoted Pierre Bourdieu, who described the traditional antithesis between culture and corporeal pleasure (or nature if you will) that was expressed by a social relationship: the opposition between a cultivated bourgeoisie and the people. In other words, critics rejected Pop because of its association with the pleasurable, which was by

20

Susan

Sontag,

Notes

on

Camp,

Partisan

Review

31

(Fall

1964):

515-16,

530.

21 Most notably seen in Vivian Gornick, Pop Goes Homosexual: Its a Queer Hand Stoking the Campfire,

The Village Voice, 7 April 1966, 1, 20-21.

definition common and kitsch.22 The Pop artists easygoing personalities and commercial success, their arts obvious humor, and their use of eroticism all emphasized the pleasurable aspects of their art and a consequential association with the non-elite masses that were the intended market of the creators of Pops original sources of imagery. Little had been more reviled, repressed and kitsch in America than the open,

pleasurable enjoyment of sexualitythe reaction to the publication of Kinseys famous works was proof enough of that. Sex was an integral part of popular culture, however. Pinups, pornography, and comic books: all of these utilized eroticism, and all were at the bottom of the kitsch barrel. Pop artists initially sought a variety of kitsch imagery from popular culture as a revolutionary alternative to modernist abstraction. But if an artist really wanted to turn his back on modernist formalism, he could do more than just copy a comic bookhe could copy an erotic comic book. By injecting elements of sexuality, the Pop artists were able to increase the trashy connotations of their work and begin the overturning of modernist dogma that was eventually to create a basis for postmodernism.

22 In Paul Taylor, ed., Post-Pop Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press and Flash Art Books, 1989), 94, 104-05.

You might also like

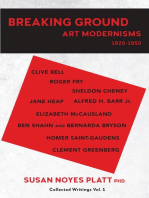

- Breaking Ground: Art Modernisms 1920-1950, Collected Writings Vol. 1From EverandBreaking Ground: Art Modernisms 1920-1950, Collected Writings Vol. 1No ratings yet

- HH Arnason - Pop Art and Europes New Realism (Ch. 21)Document46 pagesHH Arnason - Pop Art and Europes New Realism (Ch. 21)Kraftfeld100% (1)

- UNIT FOUR 4 Birthing Women ArtistsDocument8 pagesUNIT FOUR 4 Birthing Women ArtistsArgene Á. ClasaraNo ratings yet

- Women Art and Power by Yolanda Lopéz and Eva BonastreDocument5 pagesWomen Art and Power by Yolanda Lopéz and Eva BonastreResearch conference on virtual worlds – Learning with simulationsNo ratings yet

- Oscar Wildes Salomé 1Document15 pagesOscar Wildes Salomé 1Souss OuNo ratings yet

- Naïve ArtDocument5 pagesNaïve ArtKelvin Mattos100% (1)

- Oldenburg and DubuffetDocument29 pagesOldenburg and Dubuffetcowley75No ratings yet

- The Roaring TwentiesDocument17 pagesThe Roaring TwentiesAlexandraNicoarăNo ratings yet

- Biography of Oscar WildeDocument2 pagesBiography of Oscar WildeRibana RibiNo ratings yet

- HBDDocument2 pagesHBDginish12No ratings yet

- CH 3Document23 pagesCH 3madifaith10906No ratings yet

- Why Architecture Isn't ArtDocument2 pagesWhy Architecture Isn't ArtpiacabreraNo ratings yet

- Post ImpressionismDocument11 pagesPost ImpressionismAlexandra BognarNo ratings yet

- What Were The Origins of Modern Art?: Applied Art Design Bauhaus SchoolDocument13 pagesWhat Were The Origins of Modern Art?: Applied Art Design Bauhaus Schoolasdf1121No ratings yet

- HH Arnason - The School of Paris After WWI (Ch. 14)Document22 pagesHH Arnason - The School of Paris After WWI (Ch. 14)KraftfeldNo ratings yet

- How Painting Became Popular AgainDocument3 pagesHow Painting Became Popular AgainWendy Abel CampbellNo ratings yet

- Salome - Constraints of PatriarchyDocument9 pagesSalome - Constraints of PatriarchyMayank JhaNo ratings yet

- Excerpt From "The Sixth Extinction" by Elizabeth Kolbert.Document3 pagesExcerpt From "The Sixth Extinction" by Elizabeth Kolbert.OnPointRadioNo ratings yet

- Book Review of Ken Johnson's Are You Experienced?Document3 pagesBook Review of Ken Johnson's Are You Experienced?Nicolas LanglitzNo ratings yet

- Rosalind Krauss Is A Highly Influential Art Critic and Theorist Whose Career Was Launched in TheDocument2 pagesRosalind Krauss Is A Highly Influential Art Critic and Theorist Whose Career Was Launched in TheJuvylene AndalNo ratings yet

- Salome in ArtDocument11 pagesSalome in ArtemasumiyatNo ratings yet

- Whitney Museum: "Alexander Calder: The Paris Years, 1926-1933" BrochureDocument9 pagesWhitney Museum: "Alexander Calder: The Paris Years, 1926-1933" Brochurewhitneymuseum100% (9)

- CZY - Making Art GlobalDocument17 pagesCZY - Making Art GlobalJOSPHAT ETALE B.E AERONAUTICAL ENGINEER100% (1)

- Gustav Klimt Art AsiaDocument4 pagesGustav Klimt Art Asiaa.valdrigue7654No ratings yet

- 7 - Dada-1Document44 pages7 - Dada-1Mo hebaaaNo ratings yet

- Photography Extended WritingDocument8 pagesPhotography Extended Writingapi-510004852No ratings yet

- Julia Bryan-Wilson Dirty Commerce Art Work and Sex WorkDocument42 pagesJulia Bryan-Wilson Dirty Commerce Art Work and Sex WorkkurtnewmanNo ratings yet

- Moma's Paul Klee CatalogDocument39 pagesMoma's Paul Klee CatalogJulian Guerrero100% (1)

- Presentacion 1Document69 pagesPresentacion 1lorenaNo ratings yet

- Dokumen - Pub - The Crisis of Ugliness From Cubism To Pop Art Hardcovernbsped 9004366547 9789004366541 PDFDocument203 pagesDokumen - Pub - The Crisis of Ugliness From Cubism To Pop Art Hardcovernbsped 9004366547 9789004366541 PDFChristina GrammatikopoulouNo ratings yet

- Critics at Large - Excerpt From Ballerina - Sex, Scandal, and Suffering Behind The Symbol of Perfection by Deirdre Kelly PDFDocument7 pagesCritics at Large - Excerpt From Ballerina - Sex, Scandal, and Suffering Behind The Symbol of Perfection by Deirdre Kelly PDFlord GABRIEL af ROSENSVERDNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument10 pages1 PBSiddhartha Della SantinaNo ratings yet

- Francis Alys Exhibition PosterDocument2 pagesFrancis Alys Exhibition PosterThe Renaissance SocietyNo ratings yet

- E. On The Hot Seat - Mike Wallace Interviews Marcel DuchampDocument21 pagesE. On The Hot Seat - Mike Wallace Interviews Marcel DuchampDavid LópezNo ratings yet

- 07 The European Ideal BeautyDocument12 pages07 The European Ideal BeautydelfinovsanNo ratings yet

- Women in the fine arts, from the Seventh Century B.C. to the Twentieth Century A.DFrom EverandWomen in the fine arts, from the Seventh Century B.C. to the Twentieth Century A.DNo ratings yet

- Degas Odd Man OutDocument39 pagesDegas Odd Man OutJ. Michael EugenioNo ratings yet

- Leighten Picassos Collages and The Threat of WarDocument21 pagesLeighten Picassos Collages and The Threat of WarmmouvementNo ratings yet

- Modernist Magazines and ManifestosDocument25 pagesModernist Magazines and ManifestosThais PopaNo ratings yet

- Fiction and Friction Agostino Carracci's Engraved, Erotic Parody of The Toilette of VenusDocument11 pagesFiction and Friction Agostino Carracci's Engraved, Erotic Parody of The Toilette of VenusJung-Hsuan WuNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Cut o 00 WhitDocument20 pagesContemporary Cut o 00 WhitrataburguerNo ratings yet

- From Figure To AbstractionDocument9 pagesFrom Figure To AbstractionAlejandro MarreroNo ratings yet

- Saggio Di Anthea CallenDocument31 pagesSaggio Di Anthea CallenMicaela DeianaNo ratings yet

- Godfrey, Mark - The Artist As HistorianDocument35 pagesGodfrey, Mark - The Artist As HistorianDaniel Tercer MundoNo ratings yet

- Final Research Paper On BaroqueDocument11 pagesFinal Research Paper On BaroqueAarmeen TinNo ratings yet

- Balla and Depero The Futurist Reconstruction of The UniverseDocument3 pagesBalla and Depero The Futurist Reconstruction of The UniverseRoberto ScafidiNo ratings yet

- Moma Catalogue 226 300198614Document287 pagesMoma Catalogue 226 300198614Lokir CientoUnoNo ratings yet

- Sophie TaeuberDocument59 pagesSophie TaeuberMelissa Moreira TYNo ratings yet

- Carrier Manet and His InterpretersDocument17 pagesCarrier Manet and His InterpretersHod ZabmediaNo ratings yet

- Pop Art A Reactionary Realism, Donald B. KuspitDocument9 pagesPop Art A Reactionary Realism, Donald B. Kuspithaydar.tascilarNo ratings yet

- The Grid As A Checkpoint of ModernityDocument11 pagesThe Grid As A Checkpoint of ModernityHugo HouayekNo ratings yet

- Baroque Tendencies IntroDocument30 pagesBaroque Tendencies IntrobblqNo ratings yet

- Grid, Glitch and Always-On in Warhol Outer SpaceDocument35 pagesGrid, Glitch and Always-On in Warhol Outer SpaceAsta De KosnikNo ratings yet

- John Kelsey Rich Texts Selected Writing For Art 1Document125 pagesJohn Kelsey Rich Texts Selected Writing For Art 1Francesca Mangion100% (1)

- 2015 Publication Prospect - and - Perspectives ZKMDocument187 pages2015 Publication Prospect - and - Perspectives ZKMMirtes OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Foul Perfection Essays and Criticism PDFDocument259 pagesFoul Perfection Essays and Criticism PDFAdrián López Robinson100% (2)

- 271 Syllabus F2012 Final RevDocument9 pages271 Syllabus F2012 Final RevMrPiNo ratings yet

- Contrapposto: Style and Meaning in Renaissance ArtDocument27 pagesContrapposto: Style and Meaning in Renaissance ArtvolodeaTis100% (1)

- Feminity, Feminism and The Histories of ArtDocument7 pagesFeminity, Feminism and The Histories of ArtGris ArvelaezNo ratings yet

- War Is Culture: Global Counterinsurgency, Visuality, and The Petraeus DoctrineDocument18 pagesWar Is Culture: Global Counterinsurgency, Visuality, and The Petraeus DoctrineDiajanida HernándezNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Politics and InterculturalDocument208 pagesKnowledge Politics and InterculturalGris ArvelaezNo ratings yet

- Newman Talking About RevolutionDocument11 pagesNewman Talking About RevolutionGris ArvelaezNo ratings yet

- Condé Nast Traveler USA - 2017-01Document118 pagesCondé Nast Traveler USA - 2017-01pussywalkerNo ratings yet

- WOVEN Order StatusDocument906 pagesWOVEN Order StatusM A HaqueNo ratings yet

- Catherine Taylor CV/PORTFOLIODocument13 pagesCatherine Taylor CV/PORTFOLIOCatherine TaylorNo ratings yet

- Canadian Jeweller - June/July 2011 IssueDocument100 pagesCanadian Jeweller - June/July 2011 IssuerivegaucheNo ratings yet

- Sliding SlidingDocument12 pagesSliding SlidingBobWilsonNo ratings yet

- Elle UK March 2018Document294 pagesElle UK March 2018Andrada Nechifor100% (1)

- Mess Dress (Australia)Document10 pagesMess Dress (Australia)Herbert Hillary Booker 2ndNo ratings yet

- Miego NaudaDocument18 pagesMiego NaudaGabrelizzzNo ratings yet

- Acropolis Retail Data UpdateDocument279 pagesAcropolis Retail Data UpdateSergio ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Finishing and PressingDocument42 pagesFinishing and PressingKushagra Jain100% (1)

- Frank Lloyd Wright-Le CorbusierDocument60 pagesFrank Lloyd Wright-Le CorbusierDiana UrsuNo ratings yet

- Keeping Inventory - and Profits-Off The Discount Rack: Merchandise Strategies To Improve Apparel MarginsDocument12 pagesKeeping Inventory - and Profits-Off The Discount Rack: Merchandise Strategies To Improve Apparel MarginsslidesputnikNo ratings yet

- Comitatus Article - in Their Shoes in Their Shoes Shodding Yourself Unshoddily, Hobnailing Without Hobbling Etc. Etc. by Stephen KenwrightDocument8 pagesComitatus Article - in Their Shoes in Their Shoes Shodding Yourself Unshoddily, Hobnailing Without Hobbling Etc. Etc. by Stephen Kenwrightcannonfodder90No ratings yet

- 复古未来主义在当代服装设计中的应用研究 赵天爱Document71 pages复古未来主义在当代服装设计中的应用研究 赵天爱ylu870301No ratings yet

- Fashion Pitch Deck With AnimationDocument18 pagesFashion Pitch Deck With AnimationAnya Vilardo100% (2)

- Operation Breakdown ShirtDocument18 pagesOperation Breakdown ShirtAnkur KumarNo ratings yet

- Gloria - Sierra SimoneDocument52 pagesGloria - Sierra SimoneMiruna Andra MihuţNo ratings yet

- Peter EnglandDocument10 pagesPeter EnglandRakesh MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- Fashion Sense of Himachal PradeshDocument12 pagesFashion Sense of Himachal PradeshShabana Mirsa100% (1)

- Fashion, Music & Dance ExtravaganzaDocument6 pagesFashion, Music & Dance ExtravaganzanetbotesNo ratings yet

- Mario & Luigi Superstar Saga - ItemsDocument24 pagesMario & Luigi Superstar Saga - ItemsisishamalielNo ratings yet

- Case Map 3eDocument3 pagesCase Map 3emaestro9211No ratings yet

- Tepar ProductsDocument3 pagesTepar Productshill51No ratings yet

- Ip Uk NiftDocument16 pagesIp Uk Niftparidhi palNo ratings yet

- Fashion Show Production Public Relations CommitteeDocument19 pagesFashion Show Production Public Relations Committeeapi-365228469No ratings yet

- Cbmii SwarovskiDocument56 pagesCbmii Swarovskianumita24No ratings yet

- Nicolae HTE1017Document2 pagesNicolae HTE1017Roxana-Elena Nicolae KaracaNo ratings yet

- Specification Package Cover PageDocument11 pagesSpecification Package Cover PageAli ZaibNo ratings yet

- Observer Playground June 2010Document84 pagesObserver Playground June 2010Anna C. Lindow100% (1)

- The TwistDocument9 pagesThe TwistjessieharmerNo ratings yet