Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Music As Drama

Uploaded by

mastermayemOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Music As Drama

Uploaded by

mastermayemCopyright:

Available Formats

Society for Music Theory

Music as Drama Author(s): Fred Everett Maus Reviewed work(s): Source: Music Theory Spectrum, Vol. 10, 10th Anniversary Issue (Spring, 1988), pp. 56-73 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Society for Music Theory Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/745792 . Accessed: 15/02/2013 04:50

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

University of California Press and Society for Music Theory are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Music Theory Spectrum.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded on Fri, 15 Feb 2013 04:50:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Music

as

Drama

FredEverettMaus

Introduction

Recent professional music theory and analysis have tended to avoid certain large questions. Theorists have written little, explicitly at any rate, about the value of music, or the nature of musical experience. Stanley Cavell has noted that, whateverthe cause, the absence of humanemusiccriticism... seems particularlystriking against the fact that music has, among the arts, the most, perhapsthe only, systematicand precise vocabularyfor the descriptionand analysisof its objects. Somehow that possession must itself be a liability; as though one undertook to criticize a poem or novel armedwith complete control of medieval rhetoricbut ignorant of the modes of criticismdeveloped in the past two centuries.1 Joseph Kerman has also expressed regret at the limitations of professional theory and analysis. Kerman suggests that the appeal of systematicanalysiswas that it providedfor a positivistic approachto art, for a criticismthat could draw on precisely defined, seemingly objective operations and shun subjectivecriteria.2

The following have given me valuable advice and encouragement in response to earlierversions of this paper, and I am very gratefulto them: Milton Babbitt, Edward T. Cone, Joseph Dubiel, PatrickGardiner, Eric Graebner, Marjorie Hess, Katharine Maus, Alan Montefiore, James K. Randall, Eric Wefald, Peter Westergaard,and RichardWollheim. 1StanleyCavell, Must We Mean What We Say? (Cambridge:Cambridge UniversityPress, 1976), 186. 2JosephKerman, ContemplatingMusic (Cambridge:HarvardUniversity Press, 1985), 73.

Cavell and Kerman agree that the precision, definiteness, and clarity of theory and analysis have worked to discourage the study of more obscure and demanding aspects of music. It would be hard to relinquish the precision and detail that musical analysis can offer; the problem is to integrate theory and analysis somehow into a more comprehensive understanding of music. At times theorists seem simply oblivious to such issues. Allen Forte, in a paper on Schenker that is probably the best introduction to Schenker's late work, concludes with a list of unsolved problems in music theory, suggesting that Schenker's work might contribute to solutions. He mentions, for instance, the lack of a theory of rhythm in tonal music, and the lack of helpful analytical techniques for music outside the standard eighteenth- and nineteenth-century repertoire. Forte does not ask whether Schenker's work can lead to a better understanding of the importance of music, or to a convincing account of musical experience. In this Forte is more reticent than Schenker himself, whose writings are full of evaluations and speculations that go far beyond Forte's range of concerns. But Forte is silent about Schenker's broader claims, except for a footnote in which he tersely dismisses "Schenker's frequent indulgence in lengthy ontological justification of his concepts."3 Forte's paper assumes that one aspect of music, its "structure," can be distinguished from other aspects and studied separately. Other forms of inquiry might concern themselves with other aspects of music, but music theory and musical analysis, as the study of "structure," can progress independently of those other fields. Some theorists are more explicit than Forte in acknowledging areas of aesthetic inquiry that they have set aside. Fred Lerdahl and Ray Jackendoff write that

3Allen Forte, "Schenker's Conception of Musical Structure," in Maury Yeston, ed., Readingsin SchenkerAnalysis and OtherApproaches(New Haven: Yale UniversityPress, 1977). Kermanhas commentedon Forte'spaperto show the self-imposed restrictionsof professionaltheory and analysis.

This content downloaded on Fri, 15 Feb 2013 04:50:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Musicas Drama 57

anartistic concern we do notaddress is theproblem musithat here of calaffect-the interplay between music emotional and . responses . likemostcontemporary we fromaffect,for theorists, haveshiedaway it is hardto sayanything such systematic beyondcrudestatements as that To observing loudandfastmusictendsto be exciting. approach of a affect,we assume,requires better anyof the subtleties musical of musical structure.4 understanding David Epstein writesthat "the matterof 'expression'in musicis beyond the confines of these studies ... the question of what music 'says' is vast and complex and deserves separatestudy." Like Lerdahl and Jackendoff, Epstein suggests that an understanding of "expression" presupposes an understanding of "in "structure": attackingthis problem it is firstof all essential to perceive, to recognize, and to comprehendwhat it is clearly we hear, free of external or misconstruedmeanings."5These two sourcesimplythe existence of a dichotomybetween, on one hand, issues of musical "structure,"and on the other hand, issues of "affect" or "expression."In referringto "affect,"Lerdahl and Jackendofflink that partof the dichotomyto emotion. Epstein, more cautiously, relies on two differentformulations, referringto" 'expression' "and to "whata piece 'says,' "using scare-quotesand commentingthat the termsare imprecise.But evidently Epstein sees a dichotomy between, on one hand, "structure,"and on the other hand, an aspect of music analogous to the meaning of humanlanguageor gesture. Whether or not they acknowledge the existence of larger aesthetic issues, theorists generally defend the autonomy of their own studies. Even Kerman,while castigatinganalystsfor

4FredLerdahl and Ray Jackendoff, A GenerativeTheoryof Tonal Music (Cambridge:MIT Press, 1983), 8. In a footnote they add a furthercomment: "The affective content of music, we believe, lies in its exploitationof the tonal system to build dramaticstructure."This suggestionis in accordwith my argument in this paper, though Lerdahl and Jackendoff would probably find my presentationunacceptablyinformal. 5DavidEpstein, Beyond Orpheus(Cambridge:MIT Press, 1979), 11.

their narrowness,seems to leave room for such an independent area of inquiry: Theirdoggedconcentration internalrelations on withinthe single workof artis ultimately subversive faras anyreasonably as complete viewof music concerned. is Music's autonomous is structure onlyone of manyelementsthatcontribute its import.Alongwithpreoccuto withstructure theneglect othervitalmatters-not only of pation goes thewholehistorical ... butalsoeverything thatmakes else complex musicaffective, emotional, moving, expressive.6 Accordingto Kerman,analysishas usurpedthe place in musical institutionsand education that should be occupied by a more ambitiousmusic criticism.But Kermanwrites of the "autonomous structure"of music as though such a component can be isolated unproblematically: is one, though only one, of muit sic's "elements." Criticism, then, would supplement descriptions of "structure"with considerationsof historical context and with-again-an area of concernslinked somehow to human emotion. In tryingto understandwhatmusictheorycan contributeto a more generalunderstanding music, it would be naturalto beof gin with this well-entrencheddichotomy between "structure" and "affect" or "expression."Many musiciansand writerson musicbelieve that some suchdichotomyexists. If they are right, then an understanding the distinctionbetween these different of aspectsof music, and-once they are clearlydistinguished-an of understanding the relationbetween them, would be a crucial step in integratingthe insightsof musictheory into a largerpicture. In reflecting on this dichotomy, theorists can now turn to work by the philosopher Peter Kivy, who has recently distinguished between "technical" and "emotive" descriptions of music, arguingfor the musicalimportanceof emotive qualities.

6Kerman,Contemplating Music, 73.

This content downloaded on Fri, 15 Feb 2013 04:50:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

58

MusicTheorySpectrum

Kivy's essay The CordedShell begins by noting a "paradoxof musicaldescription": of Eitherdescription musiccanbe respectable, "scientific" analysis, at the familiar of losingall humanistic cost or connotations; it lapses intoits familiar emotivestanceat the costof becoming, to according themusically learned, subjective meaningless maundering.7 Kivy distinguishestwo kinds of musicaldescription,and he associateseach kindwith a differentreadership: trainedmusicians prefer technical description, while "musically untrained" music-loversare likely to findemotive descriptionattractive.So in evaluating emotive description, Kivy not only addresses a general aesthetic issue, he also addresses a practicalproblem about criticism.Professionalmusiciansmay enjoy "the healthy atmosphereof amphibrachsand enhanced dominantrelationships," but such technicaldescription leavesa largeandworthy musical out community in the cold.Music, afterall,is notjustformusicians musical and scholars, morethan any is or painting just for arthistorians, poetryfor poets. It seemsboth and that the surprising intolerable whileonecanreadwithprofit great of critics the visualandliterary without of arts beinga professor Enof untrained humanistically but glishor the history art,the musically educatedseem to face a choicebetweendescriptions musictoo of for or technical themto understand, else decried nonsense the as by authorities education taught their has themto respect.8 How should one addressthis issue? Accordingto Kivy, lanthanto takecheapshotsat technical Whatneedsdoing,rather in once againrespectable the is to makeemotivedescription guage,

eyes of the learned, so that it can stand alongside of technical description as a valid analytic tool.9

So Kivy intendshis defense of emotive descriptionas a defense of the criticismthat amateurscan read-at any rate, those amateurs who are "humanistically educated."But Kivy is not only, not primarily,concernedwith the needs of musicalamperhaps ateurs.Kivy arguesthat ascriptionsof emotionalpropertiescan be intelligible,objective, andrelevantto aestheticevaluation.If Kivy is right that emotional propertiesoften contributeto the value of a composition, then anyone who cares about music shouldwant to know about them. The emotive descriptionthat interestsKivy has two defining traits. It ascribesemotional expressivenessto the piece, rather and it than ascribingemotions to the composer or listener,?0 should be taken literally, not as "nonsense" that somehow guides the listener'sperception." Kivy associatesemotive criticism especiallywith the writingsof Donald F. Tovey, whose famous Essays in MusicalAnalysis originatedas programnotes for concertsin whichTovey appearedas conductoror pianist.12 Kivyis astute in choosingTovey to exemplifypopularcriticism: not only are Tovey's essays accessible to readers with diverse musicalbackgrounds,but manyprofessionalmusiciansandmusicalscholarsconsiderTovey one of the most insightfulanalysts, in his programnotes no less than in his more professionallyoriented works.13 Many musicianswould grantthat an interpretation and defense of Tovey's criticismis a valuableundertaking.

9Ibid., 9. l?Ibid.,6-7. 1Ibid., 9-10. introduces the discussion of emotive criticismby quoting some of 12Kivy Tovey's analyticalwriting(p. 6), and at the end of his essay he indicatesthat his argumentshave vindicated Tovey's critical practice (p. 149). Kivy mentions only one other contemporarywriter, H. C. Robbins Landon, as a practitioner of emotive description(p. 120). to 13According Joseph Kerman, "for richness, consistency, and completeness, Tovey's Beethoven stands out as the most impressiveachievement, per-

7PeterKivy, The CordedShell: Reflectionson MusicalExpression(Princeton: PrincetonUniversity Press, 1980), 9. Kivy expects that his dichotomybetween ways of describingmusic will not be novel for his readers.As he puts it, musicianswritetechnicallyat a "familiar" cost; the alternativeis the "familiar" emotive stance. 8Ibid., 8-9.

This content downloaded on Fri, 15 Feb 2013 04:50:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Musicas Drama 59

Though one is gratefulfor Kivy'sclarity,his projectis much too simplyconceived. If Kivysucceedsin defendingemotive description so that it can "stand alongside of technical description," he is left with an obvious puzzle about musical experience. When he concludes his defense of emotive description,it seems that music can be describedin two very differentways. These two ways use quite differentvocabularies,andmanypeople can only understandone kind of description,althoughboth ways of describingmusicconstitute"validcriticism."Assuming that the two kinds of descriptionbring out differentaspects of music, what is the relation of these aspects? What is it like to hear a composition that has such diverse qualities?How might the experiences of listeners with differentvocabulariesdiffer? Do the two vocabulariesrecordtwo completely differentways of experiencingmusic? Or do perceptionsof musicalstructure and perceptions of emotional expressionsimply "standalongside of' each other in musicalexperience?Or is there some way of unifyingthese differentaspectswithina singlecoherentexperience? At several points Kivy's essay touches on the relation between emotional aspectsof music and other aspects. Kivywonders whether it is possible to listen to musicwithout perceiving its expressiveness: Somepeopleclaimto, andI suppose should we taketheirwordforit. I suspect,though,thatthe mostplausible of lookingat it is as a way matter selectiveattention. listener of A can,I think,decideto focus on the expressive of qualities music,orto focuson someotheraspect instead.Whether cantotallyextirpate one one'sperception musiof cal expressiveness tend to doubt, but am prepared believeif I to to brought it.14

haps, yet produced by the art of music criticism." (Kerman, "Tovey's Beethoven," in Alan Tyson, ed., BeethovenStudies2 [London: Oxford UniversityPress, 1977], 191.) 14Kivy,The CordedShell, 59.

This is an intriguingsuggestion, but Kivy's claim that one can focus selectively on differentaspectsof music does not commit him to any view about the way a listener might integratethose aspects. When Kivy presentshis theory of musicalexpression,he argues that variousfeaturesof pieces, identifiableundertechnical descriptions,are naturallyor conventionallyexpressive.For example, he connectsmusicalcontourwith expressiveinflectionin speech, the diminishedtriad with restlessness, and the minor triadwith "the darkerside of the emotive spectrum."15 such But correlationsleave the relationbetween differentaspectsof music obscure, for it seems that emotive and technicaldescriptions interpretthe same featuresof a piece in quite differentways. A conventionalmusical analystmight try, for instance, to understand the motivic relations among the details of the piece, and he or she might try to place the details in a largermusicalprogression described in technical vocabulary. Kivy's approach takes the detailsone by one and associatesthem with emotional theirsuccessionin termsof a costates, presumably interpreting herentlydevelopingseriesof emotionalstates. Thisleaves a variant of the original puzzle about Kivy's position: can the two kinds of descriptioncome together in a single unified description of a piece, or do they reflect two fundamentallydisparate ways of regardingthe same details? No accountof music as a loose conjunctionbetween, on one hand, ingeniouslypatternedsounds, and on the other hand, expressionsor evocationsof variousemotionalstates, will be plausible. A better account must consider, much more centrally than does Kivy's essay, the extent to which a compositioncan unifyits differentaspects. Given the confusing, fragmentedimage of music in Kivy's treatment,it is easy to see why theoristslike Lerdahland Jackendoff, or Epstein, have suggested the priorityof theory and

15Ibid.,46-56, 71-83.

This content downloaded on Fri, 15 Feb 2013 04:50:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

60

MusicTheorySpectrum

formsof interpretation. Edward analysisover more humanizing T. Cone has argued similarly: "If verbalization of true content-the specific expression uniquely embodied in a work-is possible at all, it mustdependon close structural analRatherthan dismantling musicinto loosely relatedcomysis."16 ponents, these writersargue, one shouldbegin with what is solidly established-the insightsof theory and analysis-building from this knowledgetowardan understanding "affect,""exof ... pression," "content,""meaning," The discussionso far points toward an attractivebut inadequate position on the relation between music theory and the broader issues of music criticismand aesthetics. The position can be summarized four claims:(1) Musictheoryandmusical in constitute an autonomousdiscipline,capableof estabanalysis lishing its methods and achieving results without drawingon other ways of interpreting music. (2) Theoryand analysisstudy one aspectof music, namelyits "structure." The "structure" (3) of a compositionis only one of its aspects. Among the others, crucialfor criticismand aesthetics.It is hard one is particularly to name, because the common designations-"expression," "affect," "content," etc.--all imply controversial commitments. But this other aspectis closely linkedin some way to human feeling or emotion, and it may also have affinitieswith linguistic meaning. (4) An attempt to articulatethis unnamed humanisticaspectof musicmustdrawon the solid achievements of theory and analysis.Ignoringthe findingsof theoryand analysis will lead to a fragmentary,unconvincingaccount of other aspectsof music. I am in partialagreementwith this position. Certainlyit improves upon Kivy's views. Theory and analysishave achieved many insightsinto tonal music, and a more ambitiousaesthetic theorymust drawon those insightsandplace them in a convincT. 16Edward Cone, "Schubert's Promissory Note," Nineteenth Century Music 5/3 (1982): 233.

ing relationto its own claims. But I find the received notion of musical "structure,"as an aspect of music that can be distinguishedfrom "meaning,"to be vague andobscure.Further,the position that I have summarized places far too muchweight on the role of emotion in musicalexperience. It will take considerableexposition to clarifyand motivate these points of disagreement. Reflectionson a Passageby Beethoven To move toward a more general understanding music, it of will be helpful to reflectat length on a particular musicalexample. The beginning of Beethoven's String Quartet, opus 95, (Ex. 1) is richlycomplex, invitingclose scrutiny.In this section I begin with detailed description of the first seventeen measures, interruptingthe descriptiontwice for some preliminary commentary. I have not restrictedthe descriptionto the language provided by conventional music theory; rather, I have tried to articulatemy understandingof the passage as clearly and flexiblyas possible, usingmusic-theoretical languagealong with other kindsof description.After the Beethoven analysis,I move to a more general considerationof the kind of musical thoughtinstantiatedin the description.17 Analysis. Loud, aggressive,astonishinglybrief, surrounded by silence-the initial abruptoutburstleaves muchunresolved complexity, even confusion. It is strangelytimed as a whole, arrivingforcefully and apparentlydecisively-no uncertainty among the instrumentsabout the proper course-but ending so quickly, as though that gesture could feel complete and selfsufficient.It is palpablyincomplete. The clumsinessof the passage, its awkwardincompleteness,comes largelyfromits inter17By working from a detailed analysisto more general claims, obviously I run the risk that some readerswill disagreewith some or muchof the analysis. Such readersmay still find interest in the generalizationsthat follow, provided they believe that there are satisfactoryanalysesthat conformto my generalizations. (In any case, the analysis is offered as one way of hearingthe passage, one option among many for me or for any other listener.)

This content downloaded on Fri, 15 Feb 2013 04:50:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Musicas Drama 61

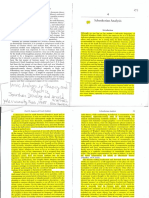

Example 1. Beethoven, StringQuartet, opus 95, beginningof firstmovement

) A Violino I ,: Allegro con brio _.-:--.

ibtbIbi '

Violino II

""

"

""

,_

'

.

-' ,'

r89

r_..-".

~f~ ~

?i W

~~~ ^ " ^ Y'

S K^*bbbb

Viola

II

Violoncello )l:Ir ' r. bM

I

Ij

I

I 1-.

0 iI

1

.1

i I

1.

IfI

*-

w LiweL

10

L--

,--

tt

|

|

I

:fbr Bbbb

bbib jLr- j_

(f

:j1 r

p

bo

ii,,.,

,t [-'.

o .

c

o.

-ILl F-

?J.

el'

~rZc

This content downloaded on Fri, 15 Feb 2013 04:50:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

62

MusicTheorySpectrum

Example 1, continued

15

rrr-Sif

cresc. ten. ten.

^

,-..,.bt

f fc^

f- t

f G~5 7

cresc.

re.,

cresc.

nal timing. The change from sixteenths to eighths articulates the opening strangely;the placingof Dl and C createsrhythmic conflictand confusion. The sixteenthnotes, alongwith the repetition of the opening F, suggest a quarter-notepulse, and to some extent that pulse gives greater weight to the Dl than to the C. But this creates a bizarreneighboringmotion, the elaborated note altering between its two appearances!The pitches are easier to understandas a line descendingfrom F to C and returningto F, passing through the pitches that most conventionally appearin ascents and descents in minor. But this latter pitchconfiguration gives specialweightto the C, contraryto the implied quarter-notepulse. Rhythmic ambivalence comes along with harmonicuncertainty. Heard as rhythmicallystressed, the Db creates some sense that D[, ratherthan C goes togetherwith the emphasized Fs and the top AN to make a backgroundtriad for these two bars;this sense is muddled or contradictedby the D in the as-

cent to F-muddled ratherthanwiped out. C, taken as partof a backgroundtriad, would give a second inversion,that is, a dissonant, unstableform, of the F-AkI-C triad.Perhapsthe C can be heardas resolvingDI, but as standingfor a V chord(extending througha consonantE at the end of the bar). Thislast might be the most satisfactoryharmonyfor the passage, but still the rhythmiclocation of the implied V is vague, and the passage does not in itself suggest such importancefor the E; so this interpretationfeels more like the listener'sdesperateimposition of a familiarstereotypethanlike a reporton the harmoniesprojected by this very passage. Commentary. The analysis uses traditional musictheoretical vocabulary and relies on traditional assumptions about tonal music-that pitch and rhythm go together most simplywhen their hierarchiesalign, that neighboringstructures normallybegin and end with the same pitch, not with an altered version of the same scale-step, and so on. Correctlabellingus-

This content downloaded on Fri, 15 Feb 2013 04:50:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Musicas Drama 63

ing theoretical vocabulary, and comparisonof the Beethoven passage to the common proceduresof musicalsuccessionsummarized in theoretical generalities, are essential parts of the analysis. But the analysisbegins by callingthe opening a loud, aggressive, abrupt outburst, calling it clumsy, incomplete. These are not technical terms of music theory. Nor do they name emotional qualities, though they do anthropomorphize the passage somewhat, describingit as one might describe a person or a human action. In the analysisthey functionas general descriptionsof the music, the theoreticaldescriptionserving to amplifyand substantiate.The clumsinessor incompleteness of the music is not hard to hear, but it is heard more precisely when one is sharply aware of the disproportioncreated by the sixteenth notes, dividing the music into a short span-but not an upbeat!-set against a much longer, slower lack of fospan, or when one is sharplyaware of the particular cus createdby skewing of pitch structureand meter. Both sorts of description-"technical" or music-theoretical,"dramatic" or anthropomorphically evocative-belong, interacting,to the analysis. If the "specifically musical"descriptionsdo not supplantthe others, then the more animistic or anthropomorphic descriptions, attributingto the piece qualities of human action-"an aggressive, abrupt outburst, forceful and apparently decisive"-need furtherattention and reflection. Analysis, continued. The next outburst (mm. 3-5) invites comparison to the first: again, loud, aggressive, and surrounded by silence, but this second attackis not quite so brief; indeed, it is long enough to seem very repetitiousby the end, even while it sustains the sense of frustratingly halting succession. The increased durationfeels like a response to the excessive brevityof the firstpassage, while the repetitiousnessmarks the response as less than successful. In other respects as well the new passageregistersan awareness of peculiaritiesof the opening and an effort to clarify,but againthere is abruptnessthroughout,and new peculiaritiesap-

pear. Response to the earlierproblemscomes in variousways. The rhythmiccomplexitiesof the openingyield to an almostobsessional clarificationand simplification.In m. 3 the firstviolin refersto the stressedsecond beat of m. 1, but now the emphasis belongs to what is obviouslyan offbeat pattern,clearlysubordinated to the strongerbeats stressed by the lower instruments. The lower instrumentsalso emphasizea divisionof the barinto halves, responding to the uncertain articulationof the third beat in m. 1. In the next measure all four instrumentsjoin to divide the bar neatly in half. And when, in the next bar, the earlier stress on the second beat appears,it no longer subverts the strengthof the firstor thirdbeat, ratherappearingas an aftereffect to the strong downbeat, almost an echo. The pullingin of the registerand move from a full triadto a bare octave not only subordinatesthe second beat to the first,but the silence on the thirdbeat is a naturalcontinuationof this fadingaway. This last effect, then, refers to the opening bar, divided into 1+3 but beats, reproducingthe disproportion renderingit appropriate and undisturbing. The passage also refersto the pitch-relatedobscuritiesof the opening, offering clean, simple reworkingsof the pitch material. The whole three-barpassage harpson the dominanttriad, vaguely suggested at the opening; and in particular,the outer parts pound on the pitch C on strong beats (even the firstviolin's offbeat patternplaces C in strongerpositionsthanin m. 1). F Earlierthere was an obscuresuggestionof a second-inversion now such a triad appearsunequivocally,emergingfrom triad; and resolving into V chords. The definitenessof the dominant harmonies,with subordinatedtonic harmoniesdistinctlyinterposed, makes the possible glimpse of V in m. 1 seem, in retrospect, too dim to be believable. To some extent this second outburst reshapes the first as essentially a long tonic chord to be succeeded by a long dominant. However, the sound of that tonic remainsclutteredwith intimationsof other harmonies. Throughoutthere is, strangely,no hint of the Dl, nor of the Dt which was at odds with it. And even more disturbingis the

This content downloaded on Fri, 15 Feb 2013 04:50:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

64

MusicTheorySpectrum

registraldiscontinuitybetween the two outbursts, the second until quite late the lower registerof the first,while disregarding without transitionan area extendinga tenth above the opening originalupper boundary.This upper region containsonly first violin Cs, whichperhapsassociatesthe pitchand registralpeculiaritiesof this response especiallywith somethinglike hysteria on the part of the first violin. More generally, the completely unmediated contrast of textures-octave-doubled theme followed by tuneless chords-gives the two passagesa mutualrepulsionthat keeps them from settlinginto anypersuasivecontinuity. So far, then, the events of this piece are a rough, abruptinitial outburst, and a second outburstwhich responds to many peculiarfeaturesof the opening but also ignoressome of its salient aspects, matching the roughness and abruptnessof the opening and combining urgent response to the first passage with a straineddisjunction. Commentary.The analysiscontinues to include specificdescriptionin music-theoreticalterms, again in interactionwith general descriptionsthat do not use specificallymusicalvocabulary. A crucial element becomes prominent: events are explained, the analysis gives reasons for their occurrence. The analysistreats the second passage as in many ways a reasoned response to the first. The first passage was rhythmicallyconfused; that gives a reason for the second passage to respond with correspondingrhythmicclarifications; rhythmicfeatures of the second passage are explainedby citingsuch reasons.The firstpassage was harmonicallyobscure;that gives a reason for the second passage to respond with correspondingharmonic clarity,retrospectivelysimplifyingthe harmonicfeel of the first passage somewhat and integratingthe two passagesinto a single clear harmonicsuccession, or tryingto. Analysis of the next few measureswill show a continuation the of this dramaof abruptaction and response, confirming apof the analysis so far but introducingno new propriateness modes of interpretation.

Analysis, concluded.The next passage, fromm. 6 to the first beat of m. 18, retracesthe precedingevents: there is a returnto the motive of the opening, then somethingwhichis like the second outburst in amounting to a long, decorated V chord. As mm. 3-5 respondedto mm. 1-2, mm. 6-18 respond,more adequately, to all the preceding events. The passage is long and continuous, continuallypurposeful,neither abruptnor repetitious. Addition of an explicit chord to the cello's repetitionof the opening motive makes the harmony unambiguous. Because the harmonyis clear, and because a meter has alreadybeen established, the placement of a passing tone on the third beat raises no special problems. In the present setting the motive seems much more straightforward. That second-beat chord hardensthe break between the sixteenth notes and eighthsin the cello motive, revivingandintensifying the earlier disproportion. But relatively unemphatic syncopations(mm. 8, 10, 12) referquietlyto the chordalattack, context, placing softer attacks in a metricallystraightforward absorbingthe blow until by m. 14 rhythmsalignsimplywith the meter-a gradual,tactfulprocedure. The previously slighted D[, now exerts its influence: the opening returnsin Gb major, which bears the same relationto the tonic key that Db bears to C, and a key in which Db is part of the tonic triad, as the first violin demonstrates. From this starting-pointthere is a slow move to the dominant. Not only does the move to V (mm. 8-9) spell out the semitone relation between the keys of Gb and F (their dominantsare connected by an utterlyliteralsemitone descent), but the Db to C connection is singledout as specialby delaysof both pitches. The strategy: since previouslythere was an outburstwith a problematic Db, and a response that seemed to ignore the Db, compensate by imitatingthe firstoutburstbut doing somethingwilderthan the Dl, was (but like the D,), and resolve it explicitlyto something like the initial response. The beginningof the responseis a little startling;it creates anothersharpbreak between contig-

This content downloaded on Fri, 15 Feb 2013 04:50:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Musicas Drama 65

uous gestures, having little to do with the tonic and dominant chords that immediately precede it; but since its motive and harmony link it primarilyto the first gesture of the piece, this local disjunctionis not as disturbingas the contrastbetween the firstand second outbursts. Explicitresolutionof the Db to C continuesin the firstviolin tune (mm. 12-15), twice by puttingDb in a muchweakerrhythmic position than C, once by puttingthe D, on the thirdbeat of the bar and resolvingit unambiguouslyto C. The firstviolin in this passage sticks to the new register it opened in bar 3; the high registerwas abruptlyand irrelevantlyopened, but now the first violin assimilates it to the other registers that have been used by repeatingin this registerthe featuresof lower registers (an F triadwith C as the lowest note, Cs neighboredby D[,s). Mm. 13-15 refer back to the earlier alternatingtonic and dominantchords, but slowly, smoothly. And ratherthan eliminating the problematic Db, these measures include it, along with D1, in clear relation to the primarychords. And then, recallingthe possible minglingof Dl and F triadsat the opening, m. 16 places a D6 triad in the position that might have been occupied by F minor, leading the Dl up to D1 while placing a chromaticlower neighbor to C, as if to diminishthe import of the Dl by providinga symmetricalsemitone neighbor,the two focal C. In place of the earlierdisclosing in on the structurally regardof the problematicD 6, here is elaborate, lucid acknowledgement of the pitch, placing it in vivid, definiterelationto F minor. The Db triadalso does muchto assimilatethe Gb sound, absorbingit and placingit in the governingtonality. The present passage occupies the combinedregistralspread of the opening outbursts,formingone seamlessspace fromregistersthat had contrastedsharply.The piece now seems to have opened a wide registralspan by successivelyopening two subspans. Withinthis space the cello has a specialrole. Havingbegun the passage by retrieving the opening motive, the cello maintainsa special concern with the beginningof the piece: its remarkableascent and descent (mm. 10-17) occupy the regis-

tral spread that was occupied at the opening by the entire ensemble, referring to those boundaries but showing them to have been narrow. The earlier textural discontinuityis absorbed into a single developing process. What felt like a jarring succession of extremes-line versus chords-now appearswithin a process of increasinglyindependent instrumentalparts. Stages of the process: octave doubling; chords, with some rhythmicdiversity;line and chords;polyphonicallyindependent,rhythmically diverse parts. The return to the opening motive and texture in m. 18 groupsthe firstseventeen measurestogetheras a separatestage of the action, and the analysis of those measures has already providedsufficientbasisfor the followingdiscussion.However, it is worth noting briefly that the issues arisingin the opening measures remain fundamentalconcernsin the continuationof the piece. The abrupt return to the opening raises new questions about the statusof Dl and now G6 as well, and the subsequent tonicizationof Db attemptsto drawthe disheveledpitch materialsinto a new stability. The major-modereturn of this materialin the recapitulationreenactsthe suppressionof Db in mm. 3-5, giving urgency to the final return of F minor. Concern about the metricalplacementand resolutionof Db persists to the last measures of the movement. Of course, to explore these later developmentsfullywould requirea lengthyanalysis. It would be naturalto call the quartet a conspicuouslydramatic composition, and the analysismakes the sense of drama concrete by narrating a succession of dramatic actions: an abrupt, inconclusive outburst; a second outburstin response, abruptand coarse in its attempt to compensate for the first;a response to the first two actions, calmer and more careful, in many ways more satisfactory. I suggest that the notion of actionis crucialin understanding the Beethoven passage. A listenerfollows the musicby drawing

This content downloaded on Fri, 15 Feb 2013 04:50:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

66

Music Theory Spectrum

on the skills that allow understanding of commonplace human action in everyday life. In transferring those skills from the context of ordinary human behavior to the more specialized context of musical events, a listener can retain some forms of interpretation relatively unchanged, while other habits of thought must be changed to fit the new context.18 In order to understand the use of these skills in hearing music, it will be helpful to begin with some generalizations about nonmusical contexts. The related notions of action, behavior, intention, agent, and so on, figure in a scheme of explanation or interpretation that applies to human beings (also, more controversially or problematically, to some animals and to sophisticated machines, for instance, chess-playing computers). The scheme works by identifying certain events as actions and offering a distinctive kind of explanation for those events. The explanations ascribe sets of psychological states to an agent, states that make the action appear reasonable to the agent and that cause the action. The explanatory psychological states can be divided roughly into epistemic states (beliefs and the like) and motivational states (desires and the like). Ascriptions of psychological states are constrained by the need for the agent to shape up as an intelligible person: fairly coherent, consistent, rational, and so on. Besides beliefs and desires, one important class of ex-

planatory states includes character traits, moods, and emotions. These functionin a varietyof ways:they can affectepistemic and motivational states, and they sometimes help to explain failuresof consistencyor rationality.19 What shows that an event is being regarded as an action? Some wordsare consistentlyassociatedwith actions;to say that some event is a theft is alwaysto classifythat event as an action. Other words sometimes designate actions, sometimes not; knocking down a snowman might be an action, but if I slip on the ice, bumping the snowman by accident, and it falls, my knockingit down is not an action. More generally,it is a necessaryconditionfor an actionthat it can be explainedby citingthe agent's reasons, by ascribingan appropriateconfigurationof psychologicalstates.20 The Beethoven analysisincludessome termsthat alwaysindicate actions. An abrupt outburst, for instance, is always an action, and so is a reasoned response. But also, the explanations the analysisgives for events in the piece, beginningespecially in the descriptionof mm. 3-5, cite reasons consistingof psychologicalstates, explainingthe events of the piece just as actions are explained. Consideragainthe analysisof mm. 3-5: manyfeaturesof the second outburstareexplainedby ascribing an intention to respond to the first outburstand beliefs about

18In focusing on musical action, and most obviously in my discussion of

fictional"musicalagents," I have been influencedby EdwardT. Cone's excellent study The Composer's Voice (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974). The importanceof that book has not yet been sufficientlyrecognizedby music theorists. To trace the precise pattern of agreement and disagreement between Cone's ideas and mine would require a separate and ratherintricate essay; here I can only record my indebtedness to his work. I encountered Roger Scruton'sfine essay "UnderstandingMusic" (in his The Aesthetic Understanding[London: Methuen, 1983]) after formulatingthe claims and arguments of this paper, but I am pleased by the similaritybetween his position and mine. Three other models that were influentialfor me: work by Flint Schierin aesthetics, and the art criticismof Adrian Stokes and MichaelFried.

19For careful and influentialexplorationsof the point, see Donald Davidson, Essayson Actions and Events(New York: OxfordUniversityPress, 1980). My account drawslargely on Davidson's views. Along with Davidson's work, G. E. M. Anscombe, Intention (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1957) was crucialin establishingthe study of action as a centralpreoccupationof current analytic philosophy. Sophisticated, engaging, recent work includes Daniel Dennett, Brainstorms (Montgomery: Bradford Books, 1978); Christopher Peacocke, Holistic Explanation(New York: Oxford University Press, 1979); Adam Morton, Framesof Mind (New York: Oxford UniversityPress, 1980); and JenniferHornsby, Actions (Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1980). 20These generalizationssimplify, but not in ways that affect the musicalapplications. For discussionof necessaryand sufficientconditionsfor an event to be an action, see Davidson, Essays, and Peacocke, Holistic Explanation.

This content downloaded on Fri, 15 Feb 2013 04:50:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Musicas Drama 67

the precise points of unclarityin the opening gesture. For instance, the descriptionpoints out that the passagepresentscertain pitch material, which was more obscurely presented before, and in depicting this as a response, it ascribes thoughts which refer to the opening, that is, thoughts that the opening had certainfeatures which make a compensatingaction appropriate. Something like this: "Thatoutburstleft a vague, equivocal sense of a dominant triad. That is unsatisfactory,and one way to deal with the situation is to present a dominant triad more straightforwardly, leaving no doubt about what I mean." The thought is ascribedto explain an action, the actionthat the thought shows as rational. More formally, one can identify beliefs-"There was something vague about the harmony at alternationof tonic and domithe opening; a straightforward nant would be much clearer"-and a desire-"I want to replace the sound of the opening with something clearer"combiningto give a reason for acting. Sayingthat the passage harpson the dominantsuggeststhat the response is repetitious and perhaps a little out of control. While the contents of mm. 3-5 warrantthis description,there trait is a furthersuggestionthat the same mood or character that led to the initial outburstcontinuesto operate, infectingthe response with a certainclumsiness,both internallyand in its relation to the firstoutburst.As with the ascriptionof thoughts,the ascriptionof mood or characterto explainevents resemblesexplanationof actual behavior. In general, the description of the Beethoven passage explains events by regardingthem as actionsand suggestingmotivation, reasons why those actions are performed, and the reasons consist of combinationsof psychologicalstates. But to whom are these ascriptions of action and thought made? It might be thought that these descriptionsare straightforward accounts of what the composer did in composing the piece, or what performersdo in performingit. Two considerations show that these suggestionsare too simple.

First, if the analysiscontainsdescriptionof an action or motivationthat cannot be ascribedto the composeror performers, and if this fact does not show that the analysisis wrong, then it seems the analysisinvolves the ascriptionof at least one action to an imaginaryagent. Consideragainthe accountof mm. 3-5: the second outburst is an abrupt, clumsy response to the first outburst. But that does not mean that Beethoven penned the opening, noticed its unresolved complexities, and hastily penned a rough response. (Maybe he did, but that is independent of what the analysis claims.) Neither is it the case that Beethoven pretendedto respond roughly and hastily; there is no sense of play or pretense about that response, whichsounds earnest. Nor does the analysis describe the actual response of the membersof the stringquartet.An essentialpartof the passage is the feeling that the first outburst has taken someone somewhat by surprise, and that the roughness of the second outburstcomes from unpreparedness.But the membersof the quartetknow what is coming next. A second consideration is more general. In listening to a piece, it is as though one follows a series of actionsthat are performednow, before one's ears, not as thoughone merelylearns of what someone (Beethoven) did years ago. And in following the musical actions, it is as though the future of the agent is open-as though what he will do next is not already determined. But then the actions are not straightforwardly those of the composer, whose (relevant) sections are all in the past, nor of the performers,whose futureactionsare alreadyprescribed. But these considerationsare not conclusive. They indicate that some kind of imaginativeactivityor constructionof fiction figuresin understandingmusic. That might involve the ascription of actions and psychologicalstates to fictionalcharacters; but it might equally, for all these argumentshave shown, involve the creation of fictionalizedversions of the composer or performers.For instance, if I follow musicalactions as though they are presentlytakingplace, I could be followingthe actions

This content downloaded on Fri, 15 Feb 2013 04:50:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

68

MusicTheorySpectrum

of imaginaryagents, but I could rather be imaginingthat the composer is presently performingthose actions. Or if I follow actions of which the future is open, I could be following the actionsof imaginaryagentsor I could be imaginingthatthe performers are improvising. The analysisdoes not answerthese questionsabout agency; indeed, at many points the Beethoven analysisis evasive about specifyingan agent. For example, "the next outburst... registers an awarenessof peculiaritiesof the openingand an effortto clarify... The whole three-barpassageharpson the dominant triad." The first sentence mentions an outburst, an awareness of something and an effort, without identifying anyone to whom these thoughtsand actionsbelong. The second sentence seems to say that a passage does something:but perhapsthis is a way of saying that the passage is a harpingon the dominant, againwithout specifyinga musicalagent. Such evasions mightseem to be omissions, gapsthat a fuller analysiswould fill. I suggest, however, that the gaps belong in the analysis, that they record an aspect of musicalexperience. The evasions reflecta pervasiveindeterminacy the identificain tion of musicalagents. Sometimesit seems appropriate think to of the whole texture of a piece as the actionof a single agent. In other contexts a differentiation of agents within the texture may be more natural,conspicuouslyin concertostyle, where a solo part interactswith an orchestra,but also in many less extreme contexts. For instance: "the first violin refers to the

stressed second beat of m. 1 . . . The lower instruments also

emphasize a division of the bar into halves." What questions about individuationdoes such a passage answer?Does it, for instance, show that the first violin part in this passage corresponds to the activityof a single agent, determinatelyset apart from the rest of the ensemble? But why not think of the first violin part as somewhat like one limb of an agent who has several limbs and can do several things at once? And what about the other three instruments-are they three agents cooperating, or a single agent producingchords?Further,the distinction

between firstviolin and lower instruments sharpin m. 3 of the is Beethoven (as described by the excerpt just quoted), but decreases in the following measures; the firstviolin retains individualityin that it contributesonly Cs, while the other instruments play more different pitches, but the rhythmic unison suggests a single chord-producingagent. And-whatever is shown by the dissociation of the first violin from the other instruments-this is only a small part of a piece in which the four instrumentscontinue to play; what does the temporary distinctnessof the firstviolin mean for the dramatis personaeof the rest of the piece? Indeed, what is the relation, in terms of the identity of the agent, between the opening outburstand mm. 3-5? The indeterminacyhere is reflected by another evasion in the language of the analysis:nowhere is it clear whetherthe response to the firstoutburstis made by the same agent or agents. If the continuity in the performingforces suggestscontinuityof the musical agency, the registral discontinuity and utterly different treatmentof the ensemble may suggest that a distinctagent or agentshave entered to respond. (Consideralso the prominence of the firstviolin in m. 3; at the opening, the firstviolin merely doublesthe second, so at m. 3 the firstviolinenterssomewhatas a new character.) Questions like these arise naturally,and they do not invite determinateanswers. The actions that a listener follows in listening to the Beethoven passage do not belong to determinately distinct agents. More precisely, as the listener discerns actions and explains them by psychologicalstates, variousdiscriminationsof agents will seem appropriate,but never with a determinacythat rules out other interpretations.The claim is not that differentlistenersmay interpretthe music differently (though they undoubtedlywill), but ratherthat a single listener's experiencewill includea play of variousschemesof individuation, none of them felt as obligatory. If this is correct,then the thoughtsconnectedwith musicare not just a matter of imaginingthe composer'sactions as occur-

This content downloaded on Fri, 15 Feb 2013 04:50:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Musicas Drama 69

ring in the present. Were that the case, indeterminacyabout the musical agent would not be possible; there would be one agent, whose actionsgive rise to the entire musicaltexture, determinatelycontinuous from beginningto end of a piece. Nor does a listener simply imagine that the performersbefore him are improvising,or otherwise cast them in dramaticroles like actors in a play; once again, a determinateset of agents would result. However, it remainspossible that the play of interpretations within this indeterminacywould include interactionsinvolving fictionalizedrepresentationsof the composer and performers. As indicated in the commentaries, the analysis mingles standardmusic-theoreticalvocabularywith other sorts of description. The anthropomorphiclanguage, I suggested, belongs to the analysisbecause the analysisreportsan experience of the music as a succession of actions. A crucialquestion remains: what is the relation between the actions I have discussed-outbursts, attempts to resolve-and the musictheoretical language of the analysis?The musicalterminology includes some phrases (e.g., "measures 7-10") that serve mainly to locate parts of the score, but also phrases(e.g., "the change from sixteenthsto eighths," "a rhythmicstrongpoint," "the pulling in of the register and move from a full triad to a bare octave") which describethe way the music sounds in performance. It is the latter language, and its relationto the more overtly dramaticlanguage, that is interesting. The firstpoint to observe is that the technicallanguageand the dramatic language offer descriptions of the same events. That event at the opening of the quartet,accordingto the analysis, is an outburst and it is also a unison passage with an obscure relation between metricalhierarchyand pitch hierarchy. The technical vocabularyof the analysis describesthe actions that make up the piece. To develop this point into something more interesting,further reflection on ordinarynon-musicalaction will be helpful. Suppose I write an address on an envelope. That action has

many different descriptions;for example, I have addressed a letter, used some ink, misspelledpartof the address,embossed the addresson one page of the enclosed letter, moved my hand in an elaborate pattern, and so forth. Some of these descriptions, but not all of them, are pertinentin understanding why I want to performthe action; or to put the point differently,the action is intentional under some descriptions, but not under others. I intentionally address a letter, I do not intentionally misspellsome words. Again, my actioncan be evaluatedin various ways accordingto variouscriteria,and given certaincriteria some descriptionswill be pertinentto evaluatingthe action while others will not. Descriptionsthat bear on evaluationwill not necessarilybe the same as those under which the action is intentional. For an evaluationof my social skills, it may be important that there are misspellingsand that the pen has made indentationson the letter in the envelope. Muchof the theoreticallanguageof the analysisnot only describesthe actionsof the piece, but describesthem in ways that show the intention with which the action is performed.To explain the second outburst, the analysisimplies an intention to respondto harmonicobscuritywith a clear alternationof dominant and tonic chords. Otherlanguage,not providinga description of an act as intentional, nonetheless providesdescriptions that pertain to evaluations that motivate subsequent actions. The metricaland harmonicobscuritiesof the firstoutburst,as it is depicted in the analysis, seem consequencesof its haste and abruptness, not features intended by the musical agent or Those obscurities, though, are recognized and motiagents.21

21This point depends on a crucialdistinctionbetween Beethoven's historical intentions and those of the agents in the piece. Suppose a dramatistwrites that a charactershould trip and fall at a certain point in a play. The dramatist intends the clumsiness,but in an importantsense it is not his or her clumsiness, and within the world of the play the clumsiness is not intentional. A similar distinctionholds for the quartet. Perhaps Beethoven intended the passage to be clumsy. Still it makes sense to say that this is not Beethoven's clumsiness, and that it is not intentional in the world of the quartet.

This content downloaded on Fri, 15 Feb 2013 04:50:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

70

MusicTheorySpectrum

vate later attempts to compensate. The theoretical language provides a descriptionthat bears on an evaluationof the passage; that descriptionthen figuresin the thoughtsof the agents of the piece when they evaluate the firstoutburstandformulate a response.22 In short, the music-theoreticallanguage in the Beethoven analysisgives descriptionsof the actions in the piece, bringing out aspects that are pertinentin describingand evaluatingthe events as actions. This point is not trivial:it shouldnot be taken for grantedthat descriptionsof actionshappen to be pertinent to their explanationand evaluation.Consider,for instance,the descriptionsthat a physiologistmight give of my bodily movements in addressinga letter, sealingit, and walkingto the mailbox. The physiologistmight produce accurateanatomicaldescriptionsof my actions, but those descriptionswould not show how I thought of the actions in decidingto performthem, nor would they be relevant for most criteria of evaluating my actions. Because of the relevance of the theoretical descriptions in explanationand evaluation, that languagealso figures in attribution thoughtto the musicalagents. of While the theoretical language of the analysis most obviously designates actions, a further indeterminacyconcerning agency enlarges the possible dramaticfunctionsof theoretical language. In everydaycontexts, there is a sharpdistinctionbetween agent and action. Agents and actions are differentsorts of things: an agent is, for instance, me, an animal of a certain size, shape, and history, while my actions are transientevents. But in musicalthought, agents and actions sometimes collapse into one another.An F minortriador the openingmotive of the Beethoven quartetmight be regardedas actions, perhapstypi22The last three paragraphs are indebted to Davidson. See especially "Agency," "The Logical Form of Action Sentences," and "The Individuation of Events," in Essays on Actions and Events. Davidson'sviews are controversial. Other positions on the individuationof actionsand events would allow me to make the same points, but in a more cumbersomeway.

cal actions of some recurringcharacter;but they might instead be regarded as agents, as characterswithin the composition. This issue does not arisein the languageof the Beethoven analysis, except perhapsin its evasiveness, but Schoenberg,for instance, writesthat "a piece of musicresemblesin some respects a photographalbum, displayingunder changingcircumstances the life of its basic idea-its basic motive,"23and similardescriptionsare common. In Schoenberg'sdescriptiona motive is treated as a dramaticcharacter.This indeterminacybetween sounds as agents and as actions is possible because a musical texture does not provide any recognizableobjects, apartfrom the sounds, that can be agents. If the sound is regarded as action, the listenermay also, seeking a perceptibleprotagonist, attribute those actions to the sounds as agents. In music, Yeats's enigma-how to tell the dancerfromthe dance-arises continuouslyand vividly. I will summarizethese points about the Beethoven analysis by comparingthe Beethoven passageto a stage-play.Comparisons between dramaand music, especiallymusicof the classical period, are commonplace,but the Beethoven analysismakesit It possible to specify the comparisonin considerabledetail.24 will be useful, for purposes of comparison,to sketch a some23ArnoldSchoenberg, Fundamentalsof Musical Composition (London: Faber and Faber, 1967), 58. and Rosen have writteninfluentiallyabout the dramaticcharacter 24Tovey of the classical style. For characteristicpassages, see Donald F. Tovey, "Sonata Forms," in his MusicalArticlesfrom the EncyclopediaBritannica(London: OxfordUniversityPress, 1944), 208-232, and CharlesRosen, TheClassical Style (New York: W. W. Norton, 1972), 70-78. Stanley Cavell, "The Avoidance of Love: A Reading of King Lear," in his MustWe Mean WhatWe Say? (New York: CharlesScribner'sSons, 1969), 267-353, includesinsightful suggestionsabout music and drama. Cavell writes about music on pp. 320-22 and 352-53, but the point of his remarksdepends on much of the rest of the essay. Elliot Carterdescribeshis own musicas dramaticin conception. See, for instance, his remarkson the Second String Quartet, in Else Stone and Kurt Stone, eds., The Writingsof Elliott Carter(Bloomington: IndianaUniversity Press, 1977), 278-79.

This content downloaded on Fri, 15 Feb 2013 04:50:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Musicas Drama 71

what simplified, idealized notion of a "normal stage play." Four propertieswill be relevant: (1) a play presents a series of actions; (2) the actions are performed by fictional characters (or fictionalized representations of mythical or historical figures);(3) for the audience, it is as thoughthe actionsare performed at the same time as the audience's perception of the actions; and (4) the series of actions forms a plot that holds the actionstogether in a unifiedstructure.I have suggestedthat the quartet, like a stage play, presents a series of actions, performed by imaginaryagents and perhapsfictionalizedversions of the composer and performers, and that these actions are heardas takingplace in the present. Regardingthe fourthproperty of a "normalstage play," the structuringof events into a plot, it may seem obvious that the issue arisesonly for an entire movement or multimovement composition, rather than the opening fragmentof a piece. but in fact a definiteplot structure is discerniblewithinthe opening barsof the quartet.For a pertinent account of plot one can turn to the work of the contemporaryliterarytheorist Tzvetan Todorov. Accordingto Todorov, an idealnarrative that beginswitha stablesituation someforcewill Fromwhich results stateof disequilibrium; theaction a of perturb. by a force directed in a converse direction,the equilibrium reis to the is established; secondequilibrium quitesimilar thefirst,butthe twoarenot identical.25

25Tzvetan Todorov, Introductionto Poetics, trans. RichardHoward (Minneapolis: Universityof MinnesotaPress, 1981). Todorov has contributedsome of the best work toward the constructionof a "grammar" narrative,analoof gous to the grammarof a language. Some other crucialworks in this areas are Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folktale, trans. Laurence Scott (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1968); Claude Levi-Strauss,"The StructuralStudy of Myth," in his Structural Anthropology, trans. Claire Jacobsen and Brooke GrundfestSchoepf (Garden City: Anchor Books, 1967);Roland Barthes, "Introduction to the StructuralAnalysis of Narrative," in his Image-MusicText, trans. Stephen Heath (London: Fontana, 1977), and S/Z, trans. Richard Miller (New York: Hill and Wang, 1974). These studies are by now somewhat dated: theoretical work on narrativehas recently concentratedmore on politi-

Todorov's remarksare very suggestivefor the general issue of musicalplot; musicianswill findit easy to thinkof manyways in whichcompositionscan conformto Todorov'sschema. (A particularlyobvious example of an "ideal narrative"would be sonata form.) In applying the schema to the opening of Beethoven's quartetone should rememberthat Todorov is describingan ideal narrativein which the plot structureis simple and complete. The Beethoven passagecan be understoodas involving a modificationof Todorov's schema, in two respects. First, the opening gesture combines the functionsof establishing an initial state of stabilityand introducingan imbalanceof to "disequilibrium": put it in a very general way, the first two bars establisha certaintonality and meter, but they do so in an obscure or confusingway, thereby introducinga problemthat needs to be resolved. A second modification of Todorov's schema appearsin the occurrenceof two attemptsto establish stability, one (in bars 3-5) that is only partlysuccessful,and a second (in the rest of the passage) that respondsmore successfully to the opening five bars. The existence of such condensation and overlappingsuggests that the Beethoven passage not only organizesits events into a plot, but does so in a particularly sophisticatedway. The analogy between the opening of the quartet and the "normalstage play" holds up fairly well. Two points that emerged earlier qualify the analogy in importantways. First, the actions in the music are not as close to everydayactions as are the actionsof nonmusicaldrama.In a stageplay, characters per-

cal, psychoanalytic,or rhetoricalissues ratherthan the narrowlyformalissues of structuralist accountsremainpromising analyses. However, the structuralist for work on musical narrative. Typically such accounts abstractfrom specific actions and individual characters while generalizing about the patterns of events within "well-formed"narratives:accordingly,this approachseems peculiarlywell-suited to bringingout similaritiesbetween musicaland nonmusical narratives.

This content downloaded on Fri, 15 Feb 2013 04:50:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

72

MusicTheorySpectrum

form actions that occur in everyday life: they make promises, argue,marry,murder,andso on. In the Beethoven passage,the actionshave general descriptionswhich can be satisfiedby eveat rydayactions:for instance,there are two outbursts the beginning of the piece, and the second one is an attemptto respondto the firstand compensatefor it. But these actionsalso have more detailed descriptions that are "specificallymusical": for instance, the second outburstrespondsto the firstby establishing a straightforward metricalpattern,by clarifying pitch structhe ture, and so on. Second, a stage play normally involves a definite number of fictionalcharactersthat can be reidentified as the same characters differentpointsin the play. Hamletis a at differentcharacterfrom Gertrude, and Hamlet in Act V is the same characteras Hamletin Act I (otherwiseone couldnot contemplate the extent to whichHamletmighthave changedin the courseof the play). But the agentsin the Beethoven passageare indeterminate. It may seem strange at first to think of music as a kind of drama that lacks determinate characters. The position may seem less strange if one recalls that Aristotle, in the Poetics, considersthe traitsof individualcharacters be less important to for a tragedy than the intelligibilityand unity of the series of actionsin the plot: of of For themostimportant allisthestructure theincidents. Tragedy is animitation, of men,butof an actionandof life ... Dramatic not of is action,therefore, not witha viewto the representation characto ter:character comesin as subsidiary the action,andof the agents witha viewto the action.26 mainly For Aristotle, the imitationof agentsin tragedyservesthe more essentialpurpose of imitatingan action. PerhapsAristotle'sremarkscan help one graspthe suggestionthat musiccan be dra-

maticwithout imitatingor representingdeterminatecharacters at all. MusicalStructure DramaticStructure as In light of the precedingdiscussion,what is the structureof the Beethoven passage?The analogyto dramasuggeststhatthe structure of the music is its plot. The structure could be summedup as three large actions, the second respondingto the first and the third respondingto both earlier actions. Or, following Todorov, one could describe the structurein terms of equilibriumand imbalance,in the slightlycomplicatedway that I indicated. But these structuresdo not imply any distinction between structureand other aspectsof the music, for all the detail of the analysis simply provides fuller specification of its plot. Nor does this accountof structurepermita distinctionbetween "structure"and a more "humanistic" "emotive" asor of the music:humanisticaspects, more preciselythe drama pect and anthropomorphism that I have discussed, are already present as aspects of the plot. But this notion of dramaticstructureis different from the notion of "structure"that appeared in the first section of this a paper. There, I cited writerswho agreedin distinguishing particularaspect of music, "structure,"that is studied in isolation from other aspects by theorists and analysts. How would one isolate the structure,in that sense, of the Beethoven passage'? In particular,does the dramaticor anthropomorphic language contributeto a descriptionof "structure"? is it closer to the Or pole of "meaning"and "expression"? This question is hardto answerwith any conviction.The notion of "structure"seems stable when it is vaguely specifiedas some sort of "patterning sounds"and placedin oppositionto of "affect," "emotion," and so on. When the picture is complicated-and given greater verisimilitude-by introduction of the dramatic aspects I have presented, the contrast breaksdown.

26Aristotle, Poetics, trans. S. H. Butcher (New York: Hill and Wang, 1961), 62-63.

This content downloaded on Fri, 15 Feb 2013 04:50:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Musicas Drama 73

The contrastbreaksdown at both ends. In light of a detailed narrationof musical drama, it becomes very implausiblethat emotion occupies a privileged role in musical experience. A writerwho believes that emotion is the only link between music and ordinaryhuman life will stress emotion heavily in explaining the importanceof music. But the Beethoven passageis connected to everyday life by action, belief, desire, mood, and so

on.27

In short, the quartet analysis, along with my subsequent commentary,does little to supportthe notion of musicalstruc27Kivy'sThe Corded Shell, as I indicated earlier, relies uncriticallyon a sharp distinction between technical and emotive descriptionof music. Curiously, however, there is a brief passage in which one can glimpse a promising unificationof his account of musical experience, along the same lines that I have been exploring. Kivy observes that to regard a piece as expressive is to regardit animistically.In order to defend the ascriptionof emotional expression to music, he argues that ascriptionof emotion to music figuresin a much more general patternof animisticconstrual: reflection the waywe talkaboutmusicwillreveal,I think,how on onlya moment's our of dedeeply "animistic" perception it reallyis. A musicalthemeis frequently scribed a "gesture." fuguesubjectis a "statement"; is "answered" the fifth as A it at of is call bythe next"statement" the theme.A "voice" stillwhatmusicians a partin a polyphonic composition,even if the partis meantto be playedon an instrument ratherthan sung by a voice. ... we must hear an auralpatternas a vehicleof or expression-an utterance a gesture-before we canhearitsexpressiveness. (Pp. 58-59) According to Kivy, the vocabularyof technicaldescriptionrevealsthat musical events are sometimes construedas utterancesor gestures, and it is such utterances or gestures that provide the basis for the ascriptionof emotion. The dichotomy between technical and emotive aspects of music governs Kivy'sthinkingso powerfullythat he can even sketch a position that eliminates the dichotomy, without being led to question the fundamentalimportanceof the dichotomy.

ture as a patterningof sounds, the appropriatesubject matter of a technical discourse that remains aloof from aesthetic issues. For at least some music, a satisfactoryaccount of structure must alreadybe an aestheticallyoriented narrationof dramatic action. Evaluation and elaboration of the claims I have made can come from two obvious sources:furtherdetailed analyses, and close interpretationof major texts in musictheory and aesthetics to see whether dramaticmodels operate in these texts. The latter task is both importantand promising:in fact, it turnsout that some of the finestand most influentialtheoristsunderstand music as a drama of interactingagents. I mentioned Schoenberg's dramaticconstrual of motivic patterning;more generally, Schoenberg's Harmonielehreconstrues pitches and harmonies as agents, strugglingfor supremacy, and it is notable that his languagebecomes more animistically dramatic when he addresses the most crucial foundationalconcepts. Schenker's early work depends on a similar dramatizationof pitch relations, and his later work remains pervasivelyanimisticin the context of a very different theory. Tovey is perhaps the most obvious example of a majoranalystwho explainsmusicby providing a dramaticnarrative.(Ironically,Kivy'scentralexample of an emotive analyst turns out not to be predominantlyconcerned with emotion, but rather with narrativesin which dramatic and technical language mix freely, as in my Beethoven The quartetdescription.)28 prerequisitefor such furtherexplorations is a clear, if provisional, exposition of the concepts of musicalagency, drama,and so on, whichthe presentpaperhas attemptedto provide.

28These brief comments on major theoristssummarizedetailed interpretations that I hope to publishshortly.

This content downloaded on Fri, 15 Feb 2013 04:50:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- The Sounds of Capitalism: Advertising, Music, and the Conquest of CultureFrom EverandThe Sounds of Capitalism: Advertising, Music, and the Conquest of CultureNo ratings yet

- Music - Drastic or Gnostic?Document33 pagesMusic - Drastic or Gnostic?jrhee88No ratings yet

- Philip Bohlman, Music As RepresentationDocument23 pagesPhilip Bohlman, Music As RepresentationcanazoNo ratings yet

- Roman Ingarden's Theory of Intentional Musical WorkDocument11 pagesRoman Ingarden's Theory of Intentional Musical WorkAnna-Maria ZachNo ratings yet

- Ton de Leeuw Music of The Twentieth CenturyDocument8 pagesTon de Leeuw Music of The Twentieth CenturyBen MandozaNo ratings yet

- Jams 2007 60 1 1Document71 pagesJams 2007 60 1 1Tiago Sousa100% (1)

- Carl Dahlhaus The Idea of Absolute Music CH 1Document9 pagesCarl Dahlhaus The Idea of Absolute Music CH 1RadoslavNo ratings yet

- Revisión Pacífica de EtnomusicologíaDocument137 pagesRevisión Pacífica de EtnomusicologíaAnonymous Izo0nlkTD5No ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 212.230.168.162 On Fri, 14 Oct 2022 18:39:27 UTCDocument18 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 212.230.168.162 On Fri, 14 Oct 2022 18:39:27 UTCTomas VidalNo ratings yet

- Form and Process in Music, 1300-2014 An Analytic Sampler (Jack Boss, Heather Holmquest, Russell Knight Etc.) (Z-Library)Document342 pagesForm and Process in Music, 1300-2014 An Analytic Sampler (Jack Boss, Heather Holmquest, Russell Knight Etc.) (Z-Library)gustavoestevam100No ratings yet

- Composing Imitative Counterpoint AroundDocument59 pagesComposing Imitative Counterpoint AroundYuri BaerNo ratings yet

- Cage Cunningham Collaborators PDFDocument23 pagesCage Cunningham Collaborators PDFmarialakkaNo ratings yet

- Becker. Is Western Art Music Superior PDFDocument20 pagesBecker. Is Western Art Music Superior PDFKevin ZhangNo ratings yet

- Williams 2006Document6 pagesWilliams 2006manuel1971No ratings yet

- Cusick, S. Gender and The Cultural Work of A Classical Music PerformanceDocument34 pagesCusick, S. Gender and The Cultural Work of A Classical Music Performanceis taken ready100% (1)

- Composing Imitative Counterpoint Around PDFDocument59 pagesComposing Imitative Counterpoint Around PDFYuri Baer100% (1)

- How To (Not) Teach CompositionDocument14 pagesHow To (Not) Teach CompositionAndrew100% (1)

- Benjamin Gerald - Sonido13 PDFDocument37 pagesBenjamin Gerald - Sonido13 PDFMariana Hijar100% (1)

- Anne C. Shreffler, "Musical Canonization and Decanonization in The Twentieth Century,"Document17 pagesAnne C. Shreffler, "Musical Canonization and Decanonization in The Twentieth Century,"sashaNo ratings yet

- Categorical Conventions in Music Discourse Style and Genre ALLAN MOOREDocument12 pagesCategorical Conventions in Music Discourse Style and Genre ALLAN MOORELeonardo AguiarNo ratings yet

- Straus - Post Structuralism and Music Theory Response To Adam KrimsDocument3 pagesStraus - Post Structuralism and Music Theory Response To Adam KrimsJoão CorrêaNo ratings yet

- Stravinsky AnalysisDocument6 pagesStravinsky Analysisapi-444978132No ratings yet

- Ben Johnston - The Corporealism of Harry PartchDocument14 pagesBen Johnston - The Corporealism of Harry PartchGeorge Christian Vilela Pereira100% (1)

- Music and Spatial VerisimilitudeDocument210 pagesMusic and Spatial VerisimilitudeAlan Ahued100% (1)

- The Schoenberg-Schenker Dispute and The Incompleteness ofDocument8 pagesThe Schoenberg-Schenker Dispute and The Incompleteness ofDaniel Roi Calingasan100% (1)

- Musical Form in The Age of Beethoven Selected Writings On Theory and Method 1998 PDFDocument223 pagesMusical Form in The Age of Beethoven Selected Writings On Theory and Method 1998 PDFCosmin PostolacheNo ratings yet

- Debussy in PerspectiveDocument4 pagesDebussy in PerspectiveBelén Ojeda RojasNo ratings yet

- Country Music Records: A Discography, 1921-1942: Tony RussellDocument1,198 pagesCountry Music Records: A Discography, 1921-1942: Tony RussellElisandro T CostaNo ratings yet

- Roesner - The Origins of W1Document52 pagesRoesner - The Origins of W1santimusic100% (1)

- Title of The Piece Name of The Composer Period/date of Composition Genre Stylistic CharacteristicsDocument2 pagesTitle of The Piece Name of The Composer Period/date of Composition Genre Stylistic CharacteristicsJohn HowardNo ratings yet

- 01 Cook N 1803-2 PDFDocument26 pages01 Cook N 1803-2 PDFphonon77100% (1)

- InsideASymphony Per NorregardDocument17 pagesInsideASymphony Per NorregardLastWinterSnow100% (1)

- Kim YoojinDocument188 pagesKim YoojinBob_Morabito_2828No ratings yet

- Words Music and Meaning PDFDocument24 pagesWords Music and Meaning PDFkucicaucvecuNo ratings yet

- Atonal MusicDocument6 pagesAtonal MusicBobby StaraceNo ratings yet

- Tagg. Popular Music Studies PresentationDocument37 pagesTagg. Popular Music Studies Presentationdonjuan1003No ratings yet

- Almén, Byron - Modes of AnalysisDocument39 pagesAlmén, Byron - Modes of AnalysisRicardo Curaqueo100% (1)

- Marx FormDocument26 pagesMarx FormKent Andrew Cranfill IINo ratings yet

- Ars SubtILIORDocument10 pagesArs SubtILIORextravalgoNo ratings yet

- Fartein Valen Atonality in The NorthDocument15 pagesFartein Valen Atonality in The NorthIlija AtanasovNo ratings yet

- (New Perspectives in Music History and Criticism) Holly Watkins - Metaphors of Depth in German Musical Thought - From E. T. A. Hoffmann To Arnold Schoenberg-Cambridge UniveDocument350 pages(New Perspectives in Music History and Criticism) Holly Watkins - Metaphors of Depth in German Musical Thought - From E. T. A. Hoffmann To Arnold Schoenberg-Cambridge UniveMina BožanićNo ratings yet

- Ears Have Walls Thoughts On The Listenin PDFDocument15 pagesEars Have Walls Thoughts On The Listenin PDFBernardo Rozo LopezNo ratings yet

- Life As An Aesthetic Idea of Music FullDocument192 pagesLife As An Aesthetic Idea of Music FullIlija AtanasovNo ratings yet

- Music of The Gods: Solo Song and in The Interludes For LaDocument52 pagesMusic of The Gods: Solo Song and in The Interludes For LaNathanNo ratings yet

- Cobussen - 13 Meditations On - Black AngelsDocument32 pagesCobussen - 13 Meditations On - Black AngelsBonnie Kuan-yi LeeNo ratings yet

- ViewDocument117 pagesViewFrancisco RosaNo ratings yet

- Guillaume de MachautDocument29 pagesGuillaume de MachautRUBENS PIMENTA DE PÁDUA FILHONo ratings yet

- 1002 Stravinsky Great PassacagliaDocument173 pages1002 Stravinsky Great PassacagliaHANS CASTORPNo ratings yet

- The Tonal-Metric Hierarchy - A Corpus Analysis Jon B. Prince, Mark A. SchmucklerDocument18 pagesThe Tonal-Metric Hierarchy - A Corpus Analysis Jon B. Prince, Mark A. SchmucklerSebastian Hayn100% (1)

- Analise PierroDocument21 pagesAnalise PierroAndréDamião100% (1)