Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Public Affairs Function in Dynamic Global

Uploaded by

putri_arianiCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Public Affairs Function in Dynamic Global

Uploaded by

putri_arianiCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Public Affairs Volume 12 Number 1 pp 4760 (2012) Published online 29 January 2012 in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.

com) DOI: 10.1002/pa.1406

Academic Paper

Exploring the management of the corporate public affairs function in a dynamic global environment

Danny Moss1*, Conor McGrath2, Jane Tonge3 and Phil Harris1

1 2

University of Chester Business School, UK McGrath Public Affairs, Ireland 3 Manchester Metropolitan University, UK

This paper explores the importance and approach to managing public affairs as an increasingly important externalfacing function in corporations operating in an increasingly complex, interconnected and politicized global business environment. Drawing on evidence gathered from a multi-site case study of the public affairs function operating within a globally based consumer products company, supplemented by evidence from interviews with public affairs professionals from a cross section of other international companies, the paper examines the role played by public affairs professionals in managing the organizationalgovernmentcitizen interface and the issues that can arise from such potentially complex interactions. The paper examines a number of key factors that have inuenced the way public affairs operates and can be managed on a global scale, and highlights the challenges that global organizations face in ensuring they have an effective global public affairs presence, capable of handling the array of contingencies that any organization may have to confront in pursuing its goals. Copyright 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

INTRODUCTION

As business and particularly larger corporations have become increasingly conscious of the changing expectations held of them not only by their customers but also by a wide array of stakeholders including governments, regulators, community groups and employees (Michell et al., 1997), they have come to recognize the value of having a well-organized and professional communications and public affairs function capable of handling any contingencies that may arise that might threaten the stability and reputation of the organization (van Riel 1995; Argenti, 1998). Indeed, regulatory and legislative intervention has become a signicant potential constraint on the operations and expansion plans of many businesses. It is here that the public affairs function often comes into its own, acting as the corporate voice and advocate of business interests (Heath, 1994; Hutton et al., 2001; Cornelissen, 2004), while also seeking to assuage the concerns of opposing

*Correspondence to: Danny Moss, University of Chester Business School, Westminster Building, University of Chester, Parkgate Rd, Chester, CH 1 4BJ, UK. E-mail: D.moss@chester.ac.uk, danny5moss@gmail.com

stakeholder groups. Such challenges may well be exacerbated when corporations are operating across many international or global markets and hence across a range of governmental and regulatory regimes (Sriramesh and Vercic, 2009). The increasing complexity of many of the issues and challenges that large international organizations, in particular, may encounter nowadays has led to a growing demand for more skilled and experienced public affairs professionals, able to help resolve or combat the effects of such issues and steer organizations through what might prove threatening reputational waters. In contrast to widening recognition of the crucial role that public affairs may play within many areas of the business world, within academic circles, public affairs suffers from a degree of incoherence, at least in part because of its cross-disciplinary origins. Any discussion of public affairs appears to be widely diffused through the literature on politics, communication, marketing and management. Amongst these disciplinary elds, it is in the management literature that we nd public affairs is least well represented, which, in turn, is indicative of the barrier that many public affairs practitioners still face in gaining greater recognition for their role within their organizations.

Copyright 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

48

D. Moss et al. Public affairs is generally recognized as an externally orientated function, encompassing all corporate activities by which an organization engages with its external stakeholders, particularly those involved with public policy issues. Thus, traditionally, public affairs is typically seen to include such activities as lobbying or government relations, media relations, issues management and community relations (Post, 1982; Pedler, 2002). Yet, as already indicated, this view of public affairs does not command universal support, and a number of alternative perspectives and disciplinary boundaries have been advanced (Post et al., 1983; Stanbury, 1988; Fleisher and Blair, 1999; Richards, 2003; Hawkinson, 2005; Showalter and Fleisher, 2005). For example, Carroll (1996) has argued that corporate public affairs encompasses public policy, issues management and crisis management, whereas Marcus and Irion (1987) have suggested that corporate public affairs departments generally have four key functions government relations, issues management, PR and community affairs. In a guide written for practitioners, Thomson and John (2007) suggested a broader remit for public affairs including lobbying, media relations, crisis management, issues management, stakeholder relations and corporate social responsibility. Given an increasingly politicized business environment not just in the west but throughout the world, most major corporations have recognized that the ability to exercise some political inuence may be a crucial factor in enhancing or even realizing a businesss nancial and market performance. Here, for example, Schuler et al. (2002) maintain that The real importance of political strategy lies not just in political outcomes, but also more importantly, in the overall competitive outcomes of the rm. Understanding corporate political strategy is indispensable for making sense of competitive strategy (p. 669).

This study is set against this contradictory background, in which despite recognition of an increasingly politicized business environment, management scholars have shown little inclination to acknowledge the potential importance to organizations of a well-managed and effective public affairs function. In this study, we set out to explore whether the limited recognition of public affairs found within the management literature does, in fact, reect the reality of how the function is perceived and treated within the global business context. Here, we acknowledged that public affairs was unlikely to be found as a distinctive function in relatively small or even medium scale businesses but was more likely to be found in larger national, international and global operating companies. Focusing on a cross section of such companies, we sought to examine how the public affairs function appears to be structured, organized and managed in the international global business context. The initial focus of the study was on the geographically dispersed public affairs function of a large global consumer products company. This multi-site case study was supplemented by a further set of indepth interviews with senior public affairs professionals, drawn from a cross section of international companies. Before embarking on the eldwork stage of the study, we conducted a review of the relevant literature to help inform the approach taken and the design of the data collection methods.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Public affairs: denitions and professional identity Although there has been a signicant growth of professional interest in public affairs over the past decade or more and a growing body of academic and professional literature about public affairs (Hillman, 2002; Grifn and Dunn, 2004; Showalter and Fleisher, 2005), there is still considerable confusion about what public affairs is or how it contributes to organizational success. This confusion is perhaps hardly surprising given there is still a lack of consensus amongst public affairs scholars and professionals themselves about the meaning of the term public affairs (Fleisher and Blair, 1999; McGrath et al., 2010). Harris and Moss (2001) highlighted the challenge of broadening the recognition for public affairs and strengthening its position as a mainstream corporate function: . . . paradoxically, at a time when there are more practitioners than ever who, at least nominally, are employed in public affairs departments/functions, the term public affairs remains one that is surrounded by ambiguity and misunderstanding. In short, public affairs remains a function in search of a clear identity (p. 102). Copyright 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Managing reputation and issues Although perhaps the dominant perspective of public affairs places a focus on its responsibility for government relations and political lobbying, other perspectives of public affairs have emerged that extend its remit to embrace its role in relation to corporate reputation management (Meznar and Nigh, 1995) and also identifying the importance of issues management as a core component of the public affairs function (Heath, 2002). Meznar and Nigh (1995), for example, emphasized the notion that public affairs should have responsibility for maintaining an organizations external legitimacy by managing the interface between an organization and its socio-political environment (p. 975). The notion here is essentially that an organization must have secured a measure of social legitimacy (Shaffer, 1995) as a necessary precondition to being J. Public Affairs 12, 4760 (2012) DOI: 10.1002/pa

Managing public affairs in a position to achieve political goals (Oberman, 2008). This argument is somewhat circular in that legitimacy is something that is a necessary prerequisite for effective public affairs and is in fact constantly strengthened or damaged as a result of the rms political engagement. This duality of roles by which public affairs seeks both to inuence public policy in the organizations favour and to ensure that issues of importance to the wider world are reected within the organizations internal thinking has been characterized well by Fleisher (1998) as the effort to potentially bring alignment between organizational and public policy (p. 7). Of course, public affairs is not the only function with a degree of responsibility for managing an organizations reputation. Indeed, an extensive body of literature exists that recognizes that responsibility for an organizations corporate reputation cannot reside with any one function, be it corporate communications, public relations or public affairs, but rather is the responsibility of all externally facing functions that have the potential to inuence how the organization is perceived over time (Fombrun and Van Riel, 1997; Gray and Balmer, 1998). Academic and professional interest in the area of issues management has grown rapidly over the past decade. From a public affairs perspective, issues management represents one of the most important ways in which public affairs can contribute to the strategic management process in organizations (Stanbury, 1988; Gaunt and Ollenburger, 1995; Heugens, 2005; Issue Management Council, 2005; Lerbinger, 2006). A variety of models have been advanced over the years that attempt to capture the way in which organizations operationalize the issues management function (Jones and Chase, 1979; Chase 1984; Hainsworth and Meng, 1988; Heath, 2002). Most of these models draw the distinction between issues management and strategic planning processes, yet also recognize the link between the two. Generally, issues management is seen to make its most signicant contribution to the strategic planning process around the strategic analysis process (Chaffee, 1985; Johnson et al., 2008), assessing the degree of risk or opportunity associated with those issues identied as of greatest relevance to the organization. Here, public affairs in its issues management guise operates as a boundary-spanning function (Aldrich and Herker, 1977) on behalf of the organization, carefully scanning and analyzing the organizational environment to identify any potentially contentious developments [issues] that might have signicant implications for the strategic decisions and actions determined by the senior management team. However, as White and Dozier (1992) have pointed out, the communication practitioners (public affairs/public relations) are not the only boundary-spanning personnel in most organizations and often compete with other organizational Copyright 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

49

functions such as management information systems, marketing and R&D for this boundary-spanning responsibility, albeit each offering a differing emphasis. However, despite the potential competition between functions for control of the environmental scanning and analysis activity, the area of issues management per se generally appears to be accepted as primarily the responsibility of the public affairs/corporate communications function, albeit often working closely with senior management. Over the past two decades, there appears to have been a growing appreciation of the potential value of the public affairs function particularly amongst senior management in Western-based organizations (Heugens, 2005; Issue Management Council, 2005). However, this apparent improving status and recognition for public affairs stands in contrast with the ndings of other studies that suggest that public affairs has had only a rudimentary involvement in strategic business planning in most organizations (Post et al., 1983). Of course, studies such as those conducted by Post et al. (1983) offer only a snapshot view of the status of public affairs in the eyes of senior management at a particular time. Management perceptions of public affairs do appear to be in transition, with a number of studies suggesting public affairs has become recognized as a more strategically important organizational function over the course of the past decade (Heath, 1988; Ashley, 1996; Shaffer and Hillman, 2000; Watkins et al., 2001; Bronn and Bronn, 2002; Mahon et al., 2004). Again, some caution is needed here about drawing any such conclusions about the status of public affairs and its engagement in the strategic management of organizations because there are still relatively few detailed longitudinal studies of the role of public affairs in organizational management. Indeed, more than 10 years on from the study by Post et al., Chase and Crane (1996, p. 138) were still exhorting companies to pay equal attention to strategic prot planning and strategic policy planning by implication calling for senior management to afford greater recognition to the public affairs agenda.

Corporate political activity A signicant body of academic work now exists that is most often found under the rubric of corporate political activity, which is arguably better conceptualized and certainly more empirically driven than its public affairs counterpart (Grifn, 2005). This scholarly niche does not wholly map onto the full spectrum of what might be considered public affairs but certainly connects with its key components, most notably the area of corporate political inuence and lobbying (Windsor, 2002; Dahan, 2009). Interestingly, research in this area tends to be undertaken by business/management J. Public Affairs 12, 4760 (2012) DOI: 10.1002/pa

50

D. Moss et al. of public affairs as a corporate function is still far from being established. What does seem to emerge from the literature is something of a polarized understanding of the function with, at one extreme, a rather narrow specialized view of public affairs as essentially fullling government relations, political intelligence and lobbying role and, at the other extreme, public affairs being treated as almost a more acceptable corporate label for an array of communications-related activities ranging from lobbying or government relations to media relations, issues and crisis management, and community relations (e.g. Post, 1982; Pedler, 2002). Public affairs has also expanded its presence over the past decade from its strong North American and Western European origins to become an almost universally recognized function in what is nowadays a global business world. Indeed, it is perhaps the rapid expansion of international trade and the emergence of new economic superpowers in China, India, Russia and Latin America, as well an expanded Europe, that has been one of the key drivers in the growth of corporate interest in the public affairs function, viewing it as a key enabling function for multinational businesses seeking to grow and expand their spheres of inuence and trade in markets where there is still a strong political inuence on who and how trade takes place with. It is against this backdrop that we set out to explore how major global and international corporations have sought to organize and manage their public affairs functions across their respective business interests.

academics, whereas public affairs research has tended to be pursued largely by political scientists. This school of thought pays much closer attention than does public affairs scholarship to the question of why organizations engage in political activity. Although public affairs research predominantly examines corporate actions and behaviour, corporate political activity research begins by rst asking what motivates rms to undertake that behaviour. Here, researchers have suggested a number of factors, which promote the importance to rms of engaging in corporate political activity, some of which are particularly instructive in terms of our subsequent understanding of the way public affairs function has been organized and managed in the corporate context. First, several studies show a positive linkage between the degree to which a corporation is diversied and its propensity to engage in some form of political activity (Schuler, 1996; Hillman and Hitt, 1999; Brasher and Lowery, 2006), although it should also be noted that diversication can itself make it more rather than less difcult for any organization to decide on which public policy issues it should prioritize (Shaffer and Hillman, 2000). Second, the corporate political activity is inuenced signicantly (Dickie, 1984; Grant, 1993; Hillman and Hitt, 1999) by the degree to which a rm is dependent upon government in terms either of its sales to public authorities (e.g. pharmaceutical manufacturers in the UK or defence contractors in the US) or of the scope and intensity of regulation in its sector (such as food products or car safety). Third, competition exists not just between functional units within an organization (for resources) but also between organizations we have empirical evidence that as one organization becomes politically engaged, its competitors will be aware of this and seek to match or exceed their rivals activities (Keim et al., 1984; Gray and Lowery, 1997). Fourth, this body of research includes work (Hillman and Keim, 1995; Hillman and Hitt, 1999; Schuler et al., 2002) that considers corporate political activity in a political marketing perspective here, studies view legislators and organized interests as the supply and demand sides of public policy and consider information, money and votes as goods that may be exchanged in a political market, and nd that they correspond with elements of the public affairs toolbox. Finally, and perhaps more tenuously, research in this area also discusses (unlike traditional public affairs scholarship) the integration of a rms business or market strategy with its political strategy Keim and Baysinger (1988), Mahon and McGowan (1996) and Baron (1995), for instance, all argue that neither element can be fully effective unless it is closely allied with the other element. Summary As this review of the literature on public affairs suggests, a comprehensive universal understanding Copyright 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

METHODOLOGY

Data collection The empirical element of this research, which was conducted over a 6-month period, consisted of two major phases: a single multi-site corporate case study within a large multinational consumer goods company and a second stage of in-depth interviews with senior public affairs professionals drawn from a broad cross section of international companies. In total, interviews were conducted with 25 senior public affairs practitioners based across the globe. The initial data collection stage involved the research team meeting the regional and country heads of the public affairs team of the global consumer products company that formed the focal case study at the companys annual internal review conference. This face-to-face contact enabled the research team to establish some degree of rapport with the companys public affairs staff and overcome any initial uncertainties about cooperating fully in the study. The research team was also able to form a tentative assessment of the relative degree of experience and professional sophistication of the various members of the global public affairs team. The research team J. Public Affairs 12, 4760 (2012) DOI: 10.1002/pa

Managing public affairs also received a brieng from the companys public affairs director and had access to corporate documents about the organization of the public affairs functions and the public affairs strategy. The research team then conducted a series of in-depth interviews with 14 of the companys public affairs professionals located in ofces across the companys core operations in Europe, North America, Australasia and Africa. Because these interviewees were based in ofces around the world, most interviews were conducted by telephone or via Skype connection. With the interviewees prior permission, the interviews were all recorded for subsequent transcription and analysis. An interview topic guide was constructed and piloted with a senior member of the companys public affairs team and with other public affairs practitioners to identify any areas of ambiguity prior to undertaking the eldwork. The nal stage of the data collection built on and extended the case study research with a set of 11 further in-depth interviews with senior public affairs managers/directors drawn from a cross section of leading UK-based and internationally based companies. Interviewees were identied through the research teams contacts, from delegate lists at public affairs conferences held in London around that time and from the Whos Who in Public Affairs handbook. Here, the aim was to gather views from a cross section of industry sectors and types in order to ascertain how far the picture of the public affairs function emerging from our focal case study research might be replicated more widely across organizational types/sectors.

51

Data analysis The data collected from the interviews with senior members of the global public affairs team from the focal case study company were transcribed for detailed analysis. Given that the study essentially involved a comparative analysis of public affairs roles within different settings, the researchers elected to adopt an essentially variable-oriented approach (Miles & Huberman, 1994), inductively coding the data to aid the identication of recurring themes and patterns (Eisenhardt, 1989). Each interviewees responses were also subjected to detailed examination to determine whether the patterns that emerged in one case were replicated in others (Yin, 1994). Combining these two approaches to analyze the case interview data allowed the researchers to cycle back and forth through individual responses as well as examine themes that emerged across the global public affairs function as a whole. With the nal stage of the study, comprising indepth interviews with a further 11 senior public affairs professionals based in international companies, we used a very similar interview protocol to that employed for the interviews conducted with the global consumer products companys public affairs Copyright 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

personnel. An identical approach was taken in this analysis as employed in analyzing the data gathered from the previous set of 14 interviews. In conducting this analysis, we were conscious of Silversteins (1988) warning about the dangers of attempting to reconcile the particular and the universal the problems of attempting to reconcile the uniqueness of an individual case with the need to understand generic processes at work across cases. As Silverstein argued, each individual has a specic history that can colour his or her perceptions and hence individual reporting. The research team was conscious of these potential dangers inherent in the analysis and the problems of possible bias associated with the data collection method (Kvale, 1988), all of which could lead to some potential misinterpretation of the data. To help guard against such errors and potential bias in the interpretation of the data collected from both the case study and further external interviews, the research team put a number of checks and balances in place. First, to help check the accuracy and consistency of data collected particularly from company case study interviews, the research team was able to refer to the documentary evidence about the companys public affairs function and its strategy provided by the corporate headquarters. Second, to address any potential errors and bias in the way the interview data was coded and interpreted (Kvale, 1988), the researchers exchanged, explored and veried each others analysis of the interview data. In this way, the researchers sought to test both the reliability and validity of the analysis in terms of the consistency of the categories assigned to the data as well as the truthfulness, plausibility and credibility of the analysis advanced.

FINDINGS

Phase one multi-site case study ndings Size, structure and scope of the public affairs function The rst notable observation to emerge from the investigations was the signicant variation found in the size, structure and scope of the work undertaken by the companys public affairs ofces based in different regions of the world. The differences in function size did not necessarily correspond with the geographical size of the territory or importance of the markets served by the various ofces. At one extreme, one or two ofces had only a single public affairs practitioner, albeit with support from colleagues in related departments where necessary, whereas in the largest regional or country ofces, which included the UK head ofce, there was a staff of some 810 practitioners. However, raw comparisons of functional size proved to be far from straightforward, because of a lack of consistency found in the composition and scope of the J. Public Affairs 12, 4760 (2012) DOI: 10.1002/pa

52

D. Moss et al. Reporting relationships The lack of consistency in the scope and organization of the public affairs function across the company ofces worldwide was also reected in the variations found in functional reporting relationships. In some countries (e.g. UAE and South Africa), the public affairs function reported to the country Chairman; in a number of others, it reported to the Communications Director, or in one or two cases, to the Global Public Affairs Vice President. The overall picture seemed to be an inconsistent one, with no common reporting pattern emerging. Not only were the function and its reporting relationships organized differently, but regional ofces had limited knowledge of how the function was organized elsewhere within the company, because of a lack of contact with other corporate communications/public affairs ofces outside their particular region. As one Europeanbased member of the public affairs team commented, In terms of expertise and capabilities, in Europe we are very strong. Its hard for me to speak about my colleagues anywhere else. We have very little interaction with my public affairs colleagues outside of Europe. Relationship with senior management The majority of interviewees expressed the view that at the more senior levels of management within the company, the importance and value of public affairs was recognized, even if senior management might not always fully understand what the public affairs function does. However, interviewees felt that their role and value to the company was less well understood or appreciated at the middle and lower levels of management within other functions, particularly outside the broad communications eld. The following examples illustrate this varied level of understanding of public affairs that appear to exist within the company: . . . within the communications function, I believe that there is good awareness and appreciation of the public affairs roles and value, or the value of having a public affairs team. If we move beyond that sort of limited circle of people who we deal with on a daily basis, Im afraid there is not very much awareness of the role or of the added value of public affairs. [Asian-based company interviewee] Very few people in other departments know what we are doing and few people are that interested in what we are doing . . .. [European-based company interviewee] Determining the strategic role and direction In probing how public affairs strategic priorities and policies were formulated and, equally, to what J. Public Affairs 12, 4760 (2012) DOI: 10.1002/pa

responsibilities performed by the different ofces. Here, for example, we found that the UK head ofce and other Western European ofces not only tended to be larger than more distant regional ofces, but they also tended to be populated by often highly experienced public affairs professionals, many of whom possessed either a strong political background or had worked in the political lobbying eld for many years. In contrast, many of the regional public affairs ofces outside Western Europe were staffed by practitioners with much more diverse communications or marketing backgrounds but with perhaps limited specialist public affairs experience. However, this was not always the case. The study also found a number of very experienced and obviously very capable public affairs practitioners operating in a number of the non-European ofces but often in isolation or with a very limited number of local knowledgeable staff to support them. In the case of many of the less well-resourced regional public affairs ofces, the study found that they had developed a number of more or less effective mechanisms for handling the various public affairs challenges they faced. One notable example was that of India, where the challenge of dealing with over two dozen separate state governments would have placed an impossible demand on the relatively limited public affairs resources of the companys India ofce. The solution adopted was to train up the companys factory managers in each Indian state to act as quasi-public affairs representatives, liaising with local government ofcials and leaders and ensuring that the companys position and benign inuence were recognized where appropriate. Functional titles The fact that many of the regional public affairs ofces were required to perform a broader range of communications activities than would normally be seen as part of public affairs practice was reected to a degree in the range of functional titles held by those practitioners interviewed, as well as in their functional reporting relationships. Here, the most common functional title found across the regional ofces was that of corporate communications rather than public affairs, which seemed indicative of their broader scope of responsibilities or, conversely, the lack of specialist public affairs expertise available within them. Indeed, it was acknowledged that some of the regional ofces had employed external public affairs consultant support for larger projects where necessary. The following comment captures some of the more typical views gathered from non-UK/EU-based regional company practitioners: . . . public affairs in this part of the world is not really developed . . .. you work more through your contacts and things like that .. . . We actually dont understand what public affairs is. . .. [Asianbased company interviewee]. Copyright 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Managing public affairs degree public affairs contributed to the development and implementation of corporate strategy, the research team was aware that the company had already instigated a major reorganization and restructuring of its global communications functions. The central corporate public affairs function claimed to have overall responsibility for determining the broad public affairs agenda, strategy and goals, and for setting the direction for the function as a whole but devolved responsibility for day-today public affairs operations to regional or country level. However, a somewhat differing view of the public affairs strategic priorities emerged from the interviews with public affairs practitioners based in the companys regional public affairs ofces. Although in most cases interviewees recognized that they were part of the companys global public affairs function and acknowledged that there were a number of common global issues that were relevant to all of the companys public affairs ofces, many of them emphasized that they saw their primary responsibility as servicing the needs of their regional or country ofce rather than servicing the corporate headquarters public affairs agenda. This tension between the corporate centre and regional/local operating company allegiances was, in part, a product of the devolved structure of the business as a whole but was exacerbated by both the functional reporting structures and the fact that the salaries of the regional public affairs staff were paid by the local operating company. Some typical interview responses that illustrate the difference between the views of European-based practitioners and those based in other parts of the world are captured as follows: . . . public affairs is a corporate strategy. It is what the centre has planned, and this is what we want the countries to do, so therefore theres very little buy-in from the countries, in terms of what might be on your agenda in corporate ofce. [Europeanbased company interviewee] I decide on it [the strategy], Im the one who implements it only. Basically I am the only one really who actually does public affairs for [named country] . . .. I basically have had to decide in terms of the knowledge I have about the operating environment, in terms of who are the key stakeholders who want to get involved because we accept that we do not have the capacity to engage everybody. [Asian-based company interviewee] . . . there is no meaningful global public affairs agenda, it is all very bottom-up thinking in this part of the world. [African-based company interviewee] Because of the unique nature of this area . . . the global stuff does not mean much here. [Eastern European-based company interviewee] Copyright 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

53

Factors affecting the operation of public affairs In gathering data about the structure, organization and management of the companys public affairs function, we had already begun to gain insight into the range of factors that appeared to inuence and shape the operation of the public affairs function, both positively and negatively. Here, three broad categories of factors were identied that appeared to have the greatest inuence on the conguration of the corporate public affairs functions: peoplerelated, organizational-systems/values-related and local operational context-related factors. In terms of organizational-systems/values and local context-related factors, perhaps the most potent positive inuence identied was the companys reputation and long-standing position and track record of success in many of its markets around the world, which helped ensure access to policy makers and insulate the company from criticism over any of its potentially more controversial ventures. More negative factors included the limited resources available to many regional ofces, the politically complex operating environment that a number of the regional operating companies faced and tensions created by the dual lines of reporting to regional/national company chairmen and to the corporate head ofce. In terms of people-related factors, positive inuences included the expertise of many of the more senior public affairs practitioners, who could be deployed, albeit temporarily, to support regional or national ofces that might lack sufciently experienced public affairs personnel to handle particular issues as they arose. Having strong support for public affairs from key members of the companys senior management team was also recognized as a very positive factor in ensuring that public affairs could exercise some inuence within the companys decision-making processes where necessary. More negative inuences included the varied level of public affairs experience found amongst the practitioners in a number of the companys more distant regional ofces and the lack of specic training to upgrade their knowledge and skills. Some interviewees also pointed to something of a silo mentality within the regional ofces, which militated against closer integration of the public affairs function as a whole. Some examples of comments offered by interviewees that illustrate these factors are captured below: We have people in all countries doing public affairs, but within a communications team the weakness is that these people dont have necessarily the right training or the right background to do public affairs because they are rather overall communications specialists. [European-based company interviewee] As far as the companys concerned, the headcount is a very tightly managed issue . . . Im the only J. Public Affairs 12, 4760 (2012) DOI: 10.1002/pa

54

D. Moss et al. one handling public affairs. With the current stafng levels . . . peoples roles are very overloaded and we just do the bare minimum we can. [Africanbased company interviewee] corporate communications/public affairs functions participated in this phase of the research is summarized in Table 1. Given the diversity of companies included in this stage of the research, which ranged from consumerorientated companies in the branded foods and drink sectors to industrial and chemical manufacturers, and also service organizations in the banking and insurance sectors, it is perhaps not surprising that we found signicant variations in both the organization and resourcing of the communications/public affairs function across the sample. Moreover, comparisons between these companies and the case study company were further

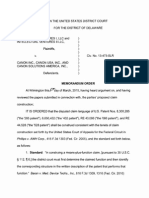

Phase two ndings from non-case public affairs practitioners The ndings from this second phase of eldwork were derived from interviews conducted with 11 senior public affairs managers/directors employed at some of the largest national and international companies. A prole of the companies whose Table 1

Company A B Sector Consumer Food Producer Beer, Spirits and Wines

Communication/public affairs functional size and structure

Department Public Affairs Corporate Relations Size Three + admin 220 spread across 19 communications hubs around the world + smaller global functional teams at HQ 20 based in head ofce and regional ofces Structure/composition Specialist European public affairs function based in Brussels Corporate communications Brand communications Media relations Employee communications Public affairs and policy CSR Alcohol policy Subdivided into stakeholder relations CSR Political analysis Regulatory and legal oversight Based around corporate communications Business communications Geographic/country communications Corporate communications Issues management Government and regulatory Corporate reputation and internal communications Media relations Public affairs and EU policy Regional affairs CSR Communications Issues management Public affairs Legal and regulatory Specialist public affairs function Government relations and lobbying Media relations Customer communications Internal communications Public affairs Education Part of policy and external relations team Handles all global reputation issues Specialist advisor to CEO on public affairs

International Banking

Corporate Affairs

Industrial Chemicals and Technology Insurance Energy and Utilities

Corporate Communication

250+ worldwide including 3035 in the European ofce mapped onto major business markets Eight with one specialist public affairs person 38 based in the head ofce plus local business communications managers

E F

Communications Public Affairs Corporate Affairs

Energy

External Corporate Affairs Public Affairs

Three people but support from legal and regulatory specialists Five handling European public affairs supported by similar teams based in North America and other Asia 30 with three working specically in public affairs

Brewing and Distribution Water and Power Utility

Group Communications

Petrochemicals

Policy and External Relations Public Affairs

Healthcare

12 in global issues and regulation + local teams supporting different business divisions in handling local/ regional issues One public affairs advisor

Copyright 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

J. Public Affairs 12, 4760 (2012) DOI: 10.1002/pa

Managing public affairs complicated by the fact that in some cases, public affairs was treated as a distinct function in its own right, whereas in others, it is treated simply as a sub-function of a broader communications or corporate affairs function. The size of the communications/public affairs function varied across the sample from, at one extreme, two companies with departments of over 200 people, albeit spread across global markets and locations, and, at the other extreme, departments comprising only two or three specialists practitioners (Table 1). The variety and complexity of the structures adopted reected, in part, the size of the functions and their respective geographic distribution. Thus, for example, Company B, a beer, spirits and wine producing company that operates on a global scale, had 220 people employed worldwide in its corporate relations department, divided between its head ofce and 19 communications hubs based across ve geographical regions. Each of these communications hubs had a relatively small team of communications staff responsible for developing and implementing the companys communications strategy at the local/regional level in terms of corporate communications, brand communications, employee communications, media relations, CSR, public affairs and public policy. An equally large communications function was found at a large multinational chemical and technology company (Company D), which comprised over 250 staff worldwide, 3035 of whom are based in the companys European head ofce with other regional centres in its major area of business. The companys communications function was structured in terms of three core components: corporate communications (corporate media relations, public affairs, corporate advertising and internal communications); business communications (marketing communications and brand public relations); and geographic communications (which focuses on communications support for operations in any one country or region and works alongside the other two components). However, such large-sized communications functions were more the exception than the rule. Our study, although obviously not representative of industry as a whole, found very few large scale communications/public affairs functions but did nd a number of medium-sized functions employing between 20 and 35 people, as well as many smaller scale departments comprising fewer than 10 people. Any meaningful discussion about the size of public affairs departments requires that we distinguish between broad corporate communications departments in which public affairs may operate as one of a number of sub-functions and dedicated public affairs specialist departments operating largely independently of the corporate communications structures. If referring specically to the numbers of people working as specialist public affairs executives/practitioners, then it Copyright 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

55

appears that in most cases, a corporate public affairs department is more likely than not to comprise fewer than a dozen people. Indeed, one very experienced interviewee who had worked for a number of major international corporations suggested that in his experience, public affairs teams of perhaps no more than four or ve were the norm in most European headquarters. Of course, the total number of public affairs staff employed by a large multinational may well multiply signicantly when taking account of the public affairs staff employed in each of the major regions/markets in which it might be operating. Reporting structure Despite varying designations and functional department sizes, virtually all the interviewees had a direct reporting line to the CEO or senior management team or to an immediate superior who themselves reported directly to the top management team within their respective organizations. In those companies where there was an extended international network of communications/public affairs ofces and personnel, there was something of a mix of devolved regional reporting coupled with, in some cases, strong central control over the function as a whole. Clearly, where the communications/public affairs function was focused on handling issues supporting local/regional business units, it was logical to nd communications/public affairs teams reporting into the senior management at the local business level. However, the interviewee at Company B, one of the larger multinational companies in the sample, highlighted the companys policy of having all of the communications/public affairs team on the central payroll in order to ensure that the centre is able to exercise clear control over priorities and the overall global strategy to be pursued: . . . the core communication goals and objectives are distilled from the corporate mission and visions both on a global basis as well as to some degree at a regional basis; there is some tension between global and local priorities but mainly in terms of the delivery as there has been a general buy-in to the mission and vision for the company, and control over the broad team is achieved from the centre because there is a hard line functional reporting system whereby all the communication function heads report directly into the corporate centre. [Interviewee at Company B] Senior management view of public affairs At the senior management level, the role and importance of public affairs appeared to be generally well appreciated in all the companies in the sample. However, interviewees acknowledged that public affairs was less well understood at lower J. Public Affairs 12, 4760 (2012) DOI: 10.1002/pa

56

D. Moss et al. issues that may have global implications for the organization up the line to the centre. Factors affecting the operation of public affairs Perhaps understandably, many of the interviewees were reluctant to discuss particular strengths or weaknesses of their own public affairs functions. Nevertheless, some themes did emerge that seemed to resonate with a number of interviewees and equally with the ndings from the case study interviews. The most frequently cited factors that contributed positively to having an effective public affairs capability were (i) the experience and expertise of the senior people working in public affairs; (ii) the networks that public affairs people normally have access to, including senior management; and (iii) having a well-established position and reputation in the markets in which you operate. In terms of adverse factors affecting the public affairs functions operations, some broadly common themes emerged from the interviews that echoed what had broadly been found at the case study phase of the research: (i) inadequate resourcing of the function; (ii) lack of understanding of public affairs away from the very top tier of management; and (iii) difculty of demonstrating/measuring the impact of public affairs to the rest of the business. The evidence from these two strands of research, on the whole, suggests a broadly similar picture of the core characteristics of the corporate public affairs function across the companies studied. Interestingly, despite more than three decades of research and an even longer period of professional practice, one of the recurring themes appears to be a notable degree of ambiguity about what exactly public affairs involves. This confusion was particularly evident amongst other functions and amongst middle and junior management in many of the organizations studied. Moreover, the studys ndings do seem to clearly point to the still emerging understanding and recognition of public affairs in different parts of the world. However, international comparisons remain problematic because differences in political systems, in the understanding and training for public affairs practitioners and in the resources committed to support public affairs all mean that it remains far from the level playing eld in terms of the way in which public affairs is organized and practiced and the inuence it has on corporate performance.

levels of management or within other functions: Public affairs is still considered as an intangible asset in many companies. They [senior management] will not give you many resources until they realize that the company can be so badly hit by legislation that they start taking it seriously. [Interviewee at Company F]. A further interesting point was made about the type of people that some companies mistakenly appoint to carry out the public affairs role: Companies still make the mistake that they put junior people into the role, and I think what you need to do is to consider the environment in which you let people loose the political environment means you need to understand your company, your products well, but you also need to understand the political environment in which decisions are made and you need them . . . that typically is something which you dont go into, either straight out of school, or even new to the company. And . . . there is no way around experience in that area. [Interviewee at Company D, an industrial chemical and technology company] Determining the strategic role and direction When asked about how communications/public affairs strategy was formulated within their organizations, there was something of a consensus that communications or public affairs strategy had to originate from and support the corporate business strategy. In some cases, there appeared to be a clearly structured process of communicating the corporate vision and goals down through the organization and ensuring all business and functional strategies align with it. In other cases, the process of linking business and communications/ public affairs was less obvious, but the latter were said to be driven by the business agenda. For example, at Company A, a global consumer food producer, there was a very clear centralized view about how strategic priorities for public affairs are set: The goals are global goals, under which our regional goals t, under which national goals t. If it doesnt t into a global goal then it isnt a priority and it isnt done, so I dont perceive any conict . . .. Although a less dogmatic view emerged from other companies, there was a more or less common recognition that some issues which affect organizations as a whole have to be given priority, and the strategy for dealing with them must come from the centre. On the other hand, it was equally recognized that in a global organization, there would inevitably be many local/regional issues that are best dealt with by people with local knowledge and contacts. However, here, it was also acknowledged that there must be a mechanism to pass local Copyright 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

DISCUSSION

Understanding of public affairs The notion of a profession characterized by a widespread sense of ambiguity and lack of clear identify that was noted in the earlier literature review (Fleisher and Blair, 1999; McGrath et al., J. Public Affairs 12, 4760 (2012) DOI: 10.1002/pa

Managing public affairs 2010) appeared to resonate strongly with the ndings of both phases of our eldwork. What was interesting is that appreciation of the value of public affairs was generally quite strong at the most senior management levels, but below this level, understanding of public affairs appeared to break down. Our study found that the confusion over the identity of public affairs that exists amongst other functions and some sections of management arguably has been exacerbated by a lack of clarity and consistency in the roles that public affairs professionals themselves have sometimes assumed. Although in some cases, the lack of resources has forced some practitioners to accept broad responsibility for a range of communications activities in addition to public affairs, in other cases, they have assumed broader communications responsibilities without what appears to be a clear understanding of the distinction between corporate communications, public relations and public affairs. Size and capability of the function Moreover, we suggest that this ambiguity about what exactly public affairs is or does may in part explain the quite varied sizes of public relations departments found across the sample. Invariably, where functions comprised relatively large numbers, this went hand-in-hand with a much broader understanding of what activities were managed under the public affairs functions banner. Indeed, some of the largest functions that we encountered certainly comprised more a mix of corporate communications and public relations than classical public affairs staff. In terms of the size of the specic public affairs teams themselves, the study found that the largest teams were located in Westernbased organizations, as well as in the European ofces of the multi-site global consumer products company. In the latter case, the European public affairs teams were signicantly larger than those found in the companys ofces based in the developing countries. We believe there may be several reasons for this disparity in the size of public affairs departments, particularly between Western-based functions and those based in ofces in Asia, Africa, the Middle East or perhaps Latin America. First, the historical development of the public affairs function has taken place largely in the West, and hence, there is a greater pool of experienced and talented professionals available to carry out the work. Second, there is a tendency for public affairs to be seen as a head ofce function, and hence, the larger ofces tend to be found close to the corporate centre, which for most of the companies studied was in Europe or the USA. Third, public affairs has tended to develop around the more complex democratic centres of government such as the EU, Washington and London, which have consequently attracted a concentration of public affairs expertise. Copyright 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Experience and expertise

57

In addition to the variation in the numbers of people working in public affairs functions across the sample organizations, it was equally noticeable that there were marked variations in the experience and background of the personnel employed in different public affairs ofces. Although it is perhaps dangerous to generalize, the public affairs staff employed in most of the Western ofces tended to possess far greater experience and expertise than their opposite numbers based in developing countries. This situation may reect differences in recruitment and training policies, or may simply be a function of the lack of talented expertise available in many of the countries where public affairs does not traditionally have a strong disciplinary base.

Managing international functional networks One of the more contentious issues to emerge from the research was that of how international and global companies can maintain control over what may be a widely dispersed network of public affairs ofces. In the case of the multi-site case study, tension existed between the corporate centre and the regionally based public affairs ofces that reported to the regional or national chairman. Locally based practitioners were faced with the dilemma of trying to satisfy a centrally determined global public affairs agenda, while responding at the same time to local priorities determined by their own operating company. In such situations, almost inevitably proximity appeared to win out, in that the public affairs function tends to bow to the more immediate pressure exerted by the local operating companys senior management team. In those companies examined where the corporate head ofce/centre was able to exert greater control over public affairs functions located around an international network of ofces, it did so by ensuring that there were clear reporting lines from the corporate centre to regionally based teams, and all of the staff in question were on a central payroll and the structures were in place to maintain tight control over the agenda setting and actions performed by practitioners on the ground.

The status of public affairs Finally, reecting on the issues of the professional status, inuence and capability of the public affairs functions across the companies examined in this study, the balance of evidence points to an increasing recognition on the part of senior management at least of the potential for public affairs to play a signicant and sometimes game-changing role helping global businesses to enter, grow or, in some cases, survive what can often be quite dynamic and sometimes politically complex business J. Public Affairs 12, 4760 (2012) DOI: 10.1002/pa

58

D. Moss et al. almost unplanned manner or, in other cases, as part of a corporate restructuring designed to cut costs or deliver greater efciency rather than having any sort of ideological inference in terms of how public affairs and other organizational communications functions are viewed and expected to be related to each other. The structural alignment of public affairs and other communications functions may vary from organization to organization, or even between divisions and regional operating companies within the same organization; all of which contributes to the general confusion about what exactly the public affairs function is supposed to do. Such ambiguity about the nature and scope of public affairs clearly does not help in establishing public affairs as an important business function. Yet, arguably pulling in the other direction is the growing politicization of the business environment in many parts of the world a trend that has been accelerated as a result of developments such as the recent global nancial crisis. In such an increasingly politicized climate, corporate business of all complexions appears to have recognized the potential for public affairs to provide it with a more powerful voice in policy-making circles to help ght against the imposition of potentially damaging new policies, legislation and regulation. The potential danger here is that in moving towards broader organizational/ corporate communications functions, the traditional public affairs skills base may be lost or at least depleted, weakening the capability of the public affairs function to full its role effectively. This was exactly the situation we discovered in a number of cases, where responsibility for public affairs was sometimes left to practitioners who might have a broad range of professional communications experience but who were perhaps relatively inexperienced in terms of public affairs expertise. In such cases, it was sometimes necessary to try to parachute in additional expertise to support local personnel on the ground. Although the use of such a ying trouble shooting team might be a viable and even a costeffective option where particularly difcult issues or potential public affairs crises arise, it cannot be a solution for sustained government relation building activity that is generally recognized as being the bedrock of effective public affairs work. To capitalize fully on the potential of public affairs to act as corporate advocate and earpiece the window-in and window-out perspective (Post, 1982) of public affairs it is vitally important that senior management understands what public affairs can and cannot achieve, what support and resources it requires to be effective, and what sort of access and power it needs if it is to help shape corporate policies to respond to, or take advantage of, what is likely to be an increasingly dynamic business environment, but also one in which government regulation or oversight may play an important part in determining the potential for corporate success. J. Public Affairs 12, 4760 (2012) DOI: 10.1002/pa

environments around the world. Here, the increasing sense of the globalization of many key issues that have the potential to impact signicantly on business was cited as one of the key drivers in elevating the status of public affairs within the corporate boardrooms of most leading global operating companies.

CONCLUSION

We believe this study offers some valuable insights into the dening characteristics of public affairs, as it is organized and managed in a cross section of international/global business organizations. The inference of this study, which also seems to be reected in previous reported research (e.g. Grifn and Dunn, 2004; Showalter and Fleisher, 2005; McGrath et al., 2010), is that for perhaps the majority of organizations, including even those with extensive international operations, public affairs remains generally something of a specialist function, often treated as part of a broader corporate communications function rather than being seen as one of the mainstream corporate functions such as nance, HRM and marketing. Paradoxically, where a mainstream communications function exists within larger domestic and/or internationally based organizations, that function is sometimes designated public affairs, even where the functions remit is predominantly concerned with corporate communications or public relations. Functional positioning and status issues aside, public affairs professionals appear to be increasingly taking on a leading role in handling organizational engagement with a range of external issues that may have signicant operational and reputational consequences, particularly those issues that have a notable regulatory or political dimension that may affect the organizations operations. The mystique that often surrounds what exactly it is that public affairs people actually do is perhaps not helped by the rather arcane world of policy negotiation and development and inuence via various lobbying strategies. The study has highlighted a distinction between what might be termed traditional public affairs departments or functions, where the focus is largely on specialist lobbying and government relations activity, and more diverse departments, where the functional designation as public affairs may simply have been carried forward from previous times or may have been consciously adopted perhaps to confer what might be perceived as greater status to what may be something of a mixed bag of communications sub-functions ranging from corporate communications/public relations, media relations, community relations and CSR to more traditional government relations and lobbying work. This dilution and expansion in the scope of work of the traditional public affairs function appears in many cases to have happened in an Copyright 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Managing public affairs

59

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Danny Moss is Professor of Corporate and Public Affairs at the University of Chester. Prior to moving to Chester, he was co-Director of the Centre for Corporate and Public Affairs at the Manchester Metropolitan University Business School, and Programme Leader for the Universitys Masters Degree in International Public Relations. He also held the post of Director of Public Relations programmes at the University of Stirling where he established the rst dedicated Masters Degree in Public Relations in then UK. He is also the co-organiser of Bledcom the annual Global Public Relations Research Symposium which is held at Lake Bled, Slovenia. Danny Moss is co-editor of the Journal of Public Affairs and author of over 80 journal articles and books; the latest of which is Public Relations: A Managerial Perspective [co-edited with Barbara Desanto]. Conor McGrath is an Independent Scholar and self-employed public affairs consultant (www. conormcgrathpa.com). He is Deputy Editor of the Journal of Public Affairs, and Practitioner Editor of Interest Groups & Advocacy. He was Lecturer in Political Lobbying and Public Affairs at the University of Ulster in Northern Ireland from 1999 to 2006. His books include Lobbying in Washington, London and Brussels: The Persuasive Communication of Political Issues (2005), Challenge and Response: Essays on Public Affairs and Transparency (2006, co-edited with Tom Spencer), Irish Political Studies Reader: Key Contributions (2008, co-edited with Eoin OMalley), and The Future of Public Trust: Public Affairs in a Time of Crisis (2008, co-edited with Tom Spencer). He has edited a collection of three books published by Edwin Mellen Press in 2009 Interest Groups and Lobbying in the United States and Comparative Perspectives; Interest Groups and Lobbying in Europe; and Interest Groups and Lobbying in Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Jane Tonge is a Senior Lecturer in Marketing Communications at Manchester Metropolitan University Business School, where she gained her doctorate. She also holds an Honours Degree in History from Cambridge University and an MA in Public Relations from Manchester Metropolitan University, where she focused on the strategic role of public relations in local government. Janes research interests are public relations, networks and networking, SMEs, gender issues and arts marketing. Jane is a former public relations practitioner, working in-house for a housing association and in local government, and as a manager in a business-to-business public relations consultancy with a range of national and international clients. She also set up and ran her own freelance public relations consultancy business. Phil Harris is Executive Dean of the Faculty of Business, Enterprise and Lifelong Learning (and Westminster Chair of Marketing and Public Affairs) at the University of Chester. He was previously Professor of Marketing at the University of Otago in Copyright 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

New Zealand, and Co-Director of the Centre for Corporate and Public Affairs at Manchester Metropolitan University Business School. He is joint founding editor of the Journal of Public Affairs and a member of a number of international editorial and advisory boards. He has published over 150 publications in the area of communications, lobbying, political marketing, public affairs, relationship marketing and international trade. His latest books are European Business and Marketing (with Frank Macdonald, 2004), The Handbook of Public Affairs (with Craig Fleisher, 2005), Lobbying and Public Affairs in the UK (2009), and The Penguin Dictionary of Marketing (2009).

REFERENCES

Aldrich H, Herker D. 1977. Boundary spanning roles and organizational structure. Academy of Management Review 2: 21730. Argenti P. 1998. Corporate Communication, 2nd edn. Irwin/ McGraw Hill: New York. Ashley WC. 1996. Anticipatory management: linking public affairs and strategic planning. In Practical Public Affairs in an Era of Change: a Communications Guide for Business, Government, and College, Dennis LB (ed.). University Press of America: Lanham, MD; 23950. Baron D. 1995. Integrated strategy: market and nonmarket components. California Management Review 37(2): 4765. Brasher H, Lowery D. 2006. The corporate context of lobbying activity. Business and Politics 8(1): 123. Bronn PS, Bronn C. 2002. Issues management as a basis for strategic orientation. Journal of Public Affairs 2(4): 24758. Carroll A. (ed.). 1996. Business & Society: Ethics and Stakeholder Management, 3rd edn. Southwestern: Cincinnati, OH. Chaffee EE. 1985. Three models of strategy. Academy of Management Review 10(1): 8998. Chase WH. 1984. Issues Management: Origins of the Future. Issue Action Publications: Stamford, CT. Chase WH, Crane TY. 1996. Issue management: dissolving the archaic division between line and staff. In Practical Public Affairs in an Era of Change: a Communications Guide for Business, Government, and College, Dennis LB (ed.). University Press of America: Lanham, MD; 12941. Cornelissen J. 2004. Corporate Communications: Theory & Practice. Sage: London. Dahan NM. 2009. The four Ps of corporate political activity: a framework for environmental analysis and corporate action. Journal of Public Affairs 9(2): 111123. Dickie RB. 1984. Inuence of public affairs ofces on corporate planning and of corporations on government policy. Strategic Management Journal 5(1): 1534. Eisenhardt KM. 1989. Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review 14: 53250. Fleisher CS. 1998. Are Corporate Public Affairs Practitioners Professionals? A Multi-region Comparison with Corporate Public Relations. Fifth Annual Bled Symposium on International Public Relations Research, Bled. Fleisher CS, Blair NM. 1999. Tracing the parallel evolution of public affairs and public relations: an examination of practice, scholarship and teaching. Journal of Communication Management 3(3): 27692. Fombrun C, Van Riel CBM. 1997. The reputational landscape. Corporate Reputation Review 1(1/2): 513. Gaunt P, Ollenburger J. 1995. Issues management revisited: a tool that deserves another look. Public Relations Review 21(3): 199210. Grant W. 1993. Business and Politics in Britain, 2nd edn. Macmillan: Basingstoke.

J. Public Affairs 12, 4760 (2012) DOI: 10.1002/pa

60

D. Moss et al.

Mahon JF, Heugens PPMAR, Lamertz K. 2004. Social networks and non-market strategy. Journal of Public Affairs 4(2): 17089. Marcus AA, Irion MS. 1987. The continued growth of the corporate public affairs function. The Academy of Management Executive 1(3): 24750. McGrath C, Moss D, Harris P. 2010. The evolving discipline of public affairs. Journal of Public Affairs 10(4): 33552. Meznar MB, Nigh D. 1995. Buffer or bridge? Environmental and organizational determinants of public affairs activities in American rms. Academy of Management Journal 38(4): 97596. Michell RK, Agle BR, Wood DJ. 1997. Towards a theory of stakeholder identication and salience: dening the principle of who and what counts. Academy of Management Review 22(4): 85386. Miles MB, Huberman AM. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: an Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd edn. Sage: Newbury Park, CA. Oberman WD. 2008. A conceptual look at the strategic resource dynamics of public affairs. Journal of Public Affairs 8(4): 24960. Pedler R. 2002. Introduction: changes in the lobbying arena: real-life cases. In European Union Lobbying: Changes in the Arena, Pedler R (ed.). Palgrave: Basingstoke; 110. Post J. 1982. Public affairs: its role. In The Public Affairs Handbook, Nagelschmidt JS (ed.). Amacom: New York; 2330. Post JE, Murray EA, Dickie RB, Mahon JF. 1983. Managing public affairs: the public affairs function. California Management Review 26(1): 13550. Richards DC. 2003. Corporate public affairs: necessary cost or value-added asset? Journal of Public Affairs 3(1): 3951. van Riel CBM. 1995. Principles of Corporate Communication. Prentice Hall: London. Schuler D. 1996. Corporate political strategy and foreign competition: the case of the steel industry. Academy of Management Journal 39(3): 720737. Schuler DA, Rehbein K, Cramer RD. 2002. Pursuing strategic advantage through political means: a multivariate approach. Academy of Management Journal 45(4): 65972. Shaffer B. 1995. Firm-level responses to government regulation: theoretical and research approaches. Journal of Management 21(3): 495514. Shaffer B, Hillman AJ. 2000. The development of business government strategies by diversied rms. Strategic Management Journal 21(2): 17590. Showalter A, Fleisher CS. 2005. The tools and techniques of public affairs. In The Handbook of Public Affairs, Harris P, Fleisher CS (eds.). Sage: London; 10922. Silverstein A. 1988. An Aristotelian resolution of the ideographic versus nomethic tension. American Psychologist 43: 42530. Sriramesh K, Vercic D. 2009. The Global Public Relations Handbook: Theory Research and Practice. Routledge: New York. Stanbury WT. 1988. BusinessGovernment Relations in Canada. Nelson: Scarborough. Thomson S, John S. 2007. Public Affairs in Practice: a Practical Guide to Lobbying. Kogan Page: London. Watkins M, Edwards M, Thakrar U. 2001. Winning the Inuence Game: What Every Business Leader Should Know about Government. John Wiley: New York. White J, Dozier DM. 1992. Public relations and management decision-making. In Excellence in Public Relations and Communications Management, Grunig JE (ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ; 91108. Windsor D. 2002. Public affairs, issues management, and political strategy: opportunities, obstacles, and caveats. Journal of Public Affairs 1(4)&2(1): 382415. Yin R. 1994. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 2nd edn. Sage Publishing: Beverly Hills, CA.

Gray ER, Balmer JMT. 1998. Managing image and corporate reputation. Long Range Planning 31(5): 68592. Gray V, Lowery D. 1997. Reconceptualizing PAC formation: its not a collective action problem, and it may be an arms race. American Politics Quarterly 25(3): 319346. Grifn JJ. 2005. The empirical study of public affairs. In The Handbook of Public Affairs, Harris P, Fleisher CS (eds.). Sage: London; 458480. Grifn JJ, Dunn P. 2004. Corporate public affairs: commitment, resources, and structure. Business & Society 43(2): 196220. Hainsworth B, Meng M. 1988. How corporations dene issue management. Public Relations Review 14(4): 1830. Harris P, Moss D. 2001. Editorial: in search of public affairs: a function in search of an identity. Journal of Public Affairs 1(2): 10210. Hawkinson B. 2005. The internal environment of public affairs: organization, process, and systems. In The Handbook of Public Affairs, Harris P, Fleisher CS (eds.). Sage: London; 7685. Heath RL. 1988. Introduction: issues management: developing corporate survival strategies. In Strategic Issues Management: How Organizations Inuence and Respond to Public Interests and Policies, Heath RL (ed.). Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA; 143. Heath RL. 1994. Management of Corporate Communications: from Interpersonal Contacts to External Affairs. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ. Heath RL. 2002. Issues management: its past, present and future. Journal of Public Affairs 2(4): 20914. Heugens PPMAR. 2005. Issues management: core understandings and scholarly development. In The Handbook of Public Affairs, Harris P, Fleisher CS. (eds.). Sage: London; 481500. Hillman AJ. 2002. Public affairs, issue management and political strategy: methodological issues that count a different view. Journal of Public Affairs 1(4)&2(1): 35661. Hillman AJ, Hitt M. 1999. Corporate political strategy formulation: a model of approach, participation and strategy decisions. Academy of Management Review 24(4): 825842. Hillman AJ, Keim G. 1995. International variation in the businessgovernment interface: institutional and organizational considerations. Academy of Management Review 20(1): 193214. Hutton JG, Goodman MB, Alexander JB, Genest CM. 2001. Reputation management: the new face of corporate public relations? Public Relations Review 27: 24761. Issue Management Council. 2005. Nine Issue Management Best Practice Indicators. Available at http://www.issuemanagement.org/documents/best_practices.htm (accessed on 8 January 2010). Johnson G, Scholes K, Wittington R. 2008. Exploring Corporate Strategy, 8th edn. Pearson Education: Harlow. Jones B, Chase H. 1979. Managing public policy issues. Public Relations Review 5(2): 320. Keim G, Baysinger B. 1988. The efcacy of business political activity: competitive considerations in a principal-agent context. Journal of Management 14(2): 163180. Keim GD, Zeithaml CP, Baysinger BD. 1984. New directions for corporate political strategy. Sloan Management Review 25(3): 5362. Kvale S. 1988. The 1000-page question. Phenomenology and Pedagogy 6(2): 90106. Lerbinger O. 2006. Corporate Public Affairs: Interacting with Interest Groups, Media, and Government. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ. Mahon JF, McGowan RA. 1996. Industry as a Player in the Political and Social Arena: Dening the Competitive Environment. Quorum Books: Westport, CT.

Copyright 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

J. Public Affairs 12, 4760 (2012) DOI: 10.1002/pa

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)