Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Arakan and Bengal Stephan Van Galen BKK March 2013-1

Uploaded by

Aung Kyaw SeinOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Arakan and Bengal Stephan Van Galen BKK March 2013-1

Uploaded by

Aung Kyaw SeinCopyright:

Available Formats

ARAKAN CONFERENCE BANGKOK 9 MARCH 2013

ARAKAN AND BENGAL

Introduction When somewhere during the first half of the fifteenth century the Venetian merchant Nicolo di Conti travelled through the Bay of Bengal he passed through the kingdom of Arakan.1 Di Conti did not have much to report about Arakan. The city of Arakan did not stand out amongst the many cities and countries he had visited.2 The only thing he recalled about Arakan was that it was situated on the bank of a river and surrounded by a tract of uninhabited mountains. For Nicolo di Conti Arakan was just another harbour en route to his next destination, the magnificent city of Ava. Four hundred years later, when the British laid siege to Mrauk U, they on the other hand were struck by the formidable remains of what appeared to have been a powerful state, but what was at that moment little more than a virtually deserted border area between the Burmese and British empires.3 The centuries between the arrival of Nicolo di Conti and the British annexation of Arakan in 1825 had apparently witnessed a remarkable expansion and subsequent decline of the Mrauk U kingdom in Arakan. [SLIDE} The Arakanese kingdom (Rakhine) grew from the fifteenth century AD from a small agrarian state with its nucleus in the heart of the Kaladan valley to a significant local power. On this late sixteenth century map by the Dutch cartographer Pieter van den Keere you will see Arakan colored yellow, although the boundaries of the kingdom are not represented correct Arakan is far too large - it still is a rather useful image that conveys rather nicely the extent of Arakans influence in the Bay of Bengal at that moment. In the first decades of the seventeenth century the Arakanese kings of Mrauk U received tribute from local rulers between Dhaka and Pegu, cities more than a thousand miles apart. The Mughal rulers of Bengal were forced to build a string of forts to defend the areas around Dhaka and Hugli against Arakanese incursions. On this slide you can see the remains of a mid-seventeenth century Mughal fort that was built to defend the Dhaka area against the invasions of the Arakanese.

1 ARAKAN AND BENGAL STEPHAN VAN GALEN

ARAKAN CONFERENCE BANGKOK 9 MARCH 2013 In my contribution to the Arakan seminar in Bangkok today I want to examine the relationship between Arakan and Bengal between the fifteenth and the eighteenth centuries. Because in my view the rise and decline of the Mrauk U kingdom was closely connected to Arakans ability to control large parts of Eastern Bengal. Arakan and Bengal The early history of the formation of the Mrauk U kingdom is not well known. From what we know today it seems the early kings slowly gained authority over the Arakanese littoral by military means and diplomacy. Mrauk U was chosen as the site for the Arakanese capital in 1430.4 According to Arakanese chronicle traditions the founding father of the Mrauk U dynasty, Man Co Mwan (c. 1404-1433), was exiled from Arakan by the king of Ava. He subsequently regained control of the kingdom after he invaded Arakan from Bengal. 5 The exact circumstances surrounding Man Co Mwans invasion are vague, but all different chronicle traditions reserve an important role for assistance provided by the Bengal sultan Jalal ud-Din (1415/6-1432/3).6 According to the Arakanese chronicles, Mrauk U would remain tributary to the Bengal sultans for several decades afterwards. The foundation myth of the Mrauk U state points to the close relations between Bengal and Arakan from at least the fifteenth century. The legendary stories surrounding the founding of Mrauk U are not confirmed by other sources; especially the involvement of the Bengal sultanate cannot be confirmed by for instance Bengali history.7 The history of the Bengal sultanate during the time of sultan Jalal ud-Din provides no clues at all to his involvement in the creation of Man Co Mwans new kingdom. Jacques Leider has pointed to the abundant use of anachronisms and the frequent erroneous references to Indian or Bengal rulers not contemporary to Man Co Mwan. Jalal ud-Din is also not named as such in the chronicles. The evidence for the existence of a tributary relationship between Arakan and Bengal afterwards is therefore very thin. In the tales about the origin of the Mrauk U kingdom, control over Arakan is however closely associated with access to Bengals resources. The importance of the foundation myths lies therefore more in the way in which the Arakanese have perceived their relationship with Bengal. Earlier examples of this close connection between Arakan and south-eastern Bengal can be traced during the Vesali period (c.600 and 1000) when Arakan and south-eastern Bengal shared a common political culture.8 There are strong indications that the Candra dynasties of the Chittagong area and Arakan were linked and that the Chittagong region was culturally and politically dominated by the descendants of the Candra dynasty from Vesali.9 Man Co Mwan was succeeded in 1434 by his brother Ali Khan (1434-1458).10 Ali Khan brought parts of the Arakanese littoral under control of Mrauk U. Chittagong remained under 2 ARAKAN AND BENGAL STEPHAN VAN GALEN

ARAKAN CONFERENCE BANGKOK 9 MARCH 2013 the control of the Bengal sultans.11 Although it seems the early Mrauk U kings established a temporary hold over the area between Chittagong and the Naf, it is unclear to which extent they were able to control the city.12 The fifteenth and early sixteenth century should therefore be described as the least known period of the Mrauk U dynasty. It seems the hold of Mrauk U over the Arakanese littoral declined and the kingdom was apparently gripped by several succession struggles.13 In 1513 the Arakanese king Man Raja was put to flight because of incursions by the Sak from Tripura. The Tripura governor of Chittagong was styled Vanquisher of Arakan following the 1513 raid on Arakan.14 In Arakanese traditions the reign of the pater patriae king Man Pa (1531-1553) is generally taken as the beginning of Arakanese control over the area around Chittagong. Firm evidence of Arakanese control over south-eastern Bengal is however first available for the reign of his son king Man Phalaung (1571-1593).15 The Arakanese chronicle traditions describing the conquests of Man Pa in Bengal are, like those pertaining to Min Co Mwan, also quite explicitly anachronistic and we must assume that they are eighteenth-century reconstructions of Man Pas reign. The importance of the claims to Arakanese sovereignty in Bengal in these stories is the way in which they legitimize the conquest of Bengal by later Arakanese kings. These chronicles claim Arakanese sovereignty over Bengal long before Man Pas first conquest.16 From an Arakanese perspective Man Pa only reclaimed what the Arakanese chroniclers call the twelve towns of Banga: this part of Bengal had according to them only been ceded to the Bengal sultans by Man Pas predecessor Man Co Mwan when he accepted Bengali aid in his attempts to recover the kingdom. In this way Man Pa not so much occupied south-eastern Bengal but restored Arakanese control over an area which had earlier belonged to the Arakanese.17 The claims to Arakanese dominion in Bengal are also illustrated by the use in sixteenth and seventeenth century Bengali, Persian, Portuguese and Dutch sources of the name Magh or Mog to denote the Arakanese dynasty. Seventeenth-century Arakanese kings were portrayed as Magh princes. Magh in this context is a corrupt form of Magadha, the birth-place of Buddhism and the seat of Buddhist culture in the Ganges delta. Bengali poets active at the seventeenth century Arakanese court frequently used terms such as the Magadha empire, or Maghi era when talking about Arakan and Arakanese rule in Bengal. In portraying themselves as heirs to the Buddhist kings of Magadha the Arakanese kings sought to legitimize their rule in south-eastern Bengal.18 On the slide you can see another way in which kings such as Man Pa made clear their right to Bengal, here we can see the king with his Arakanese and Bengali 3 ARAKAN AND BENGAL STEPHAN VAN GALEN

ARAKAN CONFERENCE BANGKOK 9 MARCH 2013 wives on either side. The adoption of titles of Bengal sultans and Muslim names is another example of how Arakanese kings made clear their claims to this part of Bengal.19 To illustrate the importance of Bengal for the success of the Mrauk U state I propose to do two things today. First I want to provide you with a glimpse of what I have come to call the Ninety Years War (c. 1574-1666) between the Mughal empire and the Mrauk-U kingdom, and second I like to discuss the economy of Arakan in the seventeenth century with you.

I will now first take you to the reign of king Sirisudhammaraja from 1622 to 1638 In 1623, one year after the young king Sirisudhamma came to the throne. The rebellious Mughal prince Shah Jahan came to Bengal, which served to destabilize the already weak Mughal position in Bengal. The unstable political situation in Bengal opened the gates for a series of devastating invasions by the Arakanese. Immediately following Shah Jahans arrival in Dhaka in May 1624 an Arakanese embassy arrived to assure the rebellious prince of the sympathy of their king Sirisudhammaraja. 20 According to the Mughal chronicler Mirza Nathan the Arakanese king possessed 10,000 warboats, 1,500 elephants, and one million infantry. On the slide you can see a mid-seventeenth century drawing by a Dutch artist that depicts Arakanese jelias or warboats- at sea near Pili on the Orissan coast. The Arakanese embassy supposedly brought a peshkash worth 100,000 Rupees, for which in return Sirisudhammaraja received robes of honour and a firman confirming him in his territories.21 The grant of this firman has a certain irony to it. The entry of Shah Jahan into Bengal probably diverted attention from the defence of the borders with Arakan. It is clear that Sirisudhammaraja, despite the meek appearance of his ambassadors before the rebellious prince, in the beginning of his reign continued his fathers campaigns into Bengal. Hendrick Lambrechts, a merchant from the Dutch East India Company, or VOC, reported in a letter to his superiors that in 1623 the young king Sirisudhammaraja returned to Arakan with no less than c. 30,000 Bengali slaves. The captives were described as strong and healthy, which the Dutch merchant ascribed to the abundance of rice and other foodstuffs in Arakan.22 In the same letter he described that the young king on 4 December 1623 paid him a visit aboard the VOCs yacht Medenblick at anchor at Urittaung. Sirisudhammaraja explained the Dutch merchant that he was at that moment setting out for a new campaign into Bengal.23 This puts the friendly reception of the Arakanese ambassadors in Dhaka by Shah Jahan in 4 ARAKAN AND BENGAL STEPHAN VAN GALEN

ARAKAN CONFERENCE BANGKOK 9 MARCH 2013 May 1624 in a different perspective. It now seems that it was probably Shah Jahan who thought to profit most from a friendship with the powerful Arakanese Raja. After the 1623 raid, it seems that Sirisudhammaraja in 1624, perhaps after his ambassadors had visited Shah Jahan in Dhaka, raided Bhalua, returning to Arakan with a rich booty. 24 After the defeat of Shah Jahan by Jahangir, Mahabat Khan was installed by the emperor Jahangir as subahdar of Bengal, who in his turn left his son Khanahzad Khan as governor of Bengal. The extent of the Arakanese incursions after the departure of Shah Jahan is illustrated by a report from Jan van der Burch, a VOC merchant who was in Mrauk U in December 1625. On 5 December 1625 Jan van der Burch described that the king had brought from Bengal 10,000 slaves. According to the Dutch merchant these slaves were the result of last years campaign when Sirisudhammaraja had conquered Sripur.25 Possibly because of the threat of Arakanese invasion the new governor of Bengal Khanahzad Khan did not reside at Dhaka. Khanahzad Khan instead installed others as deputy governors in Dhaka.26 The Mughal deputies would be confronted with the full force of the Arakanese when the young king in 1626 marched on Dhaka.27 The Fatiyyah-i-ibriyyah contemporary Mughal chronicle - describes how during their government Dhaka was sacked by Sirisudhammaraja.28 The sack of Dhaka would have taken place somewhere early in 1626 as in June 1626 following Mahabat Khans defection to Shah Jahan, Khanazad Khan was recalled from Bengal and as a consequence his deputies were recalled from Dhaka as well.29 The Fatiyyah-i-ibriyyah describes how the Arakanese set fire to the Mughal capital of Bengal, plundered its surroundings, and led the populace away as slaves.30 The recall of Khanahzad Khan was followed by a quick succession of governors which served to further destabilize Bengal. The Dutch governor-general Coen reported that every month new governors arrived who all tried in vain to clean up the mess.31 The death of Jahangir in October 1627 had again a negative impact on the Mughals capability to rule effectively in Bengal.32 The sack of Dhaka initiated the collapse of Mughal authority in south-eastern Bengal. The fact that a steady flow of slaves kept the VOC coming back to Arakan suggests that Bengal continued to pay tribute to the Arakanese crown following the sack of Dhaka. In 1628 the Dutch governor-general Pieter De Carpentier (1623-1627) in his final report to the directors in the Netherlands described Sirisudhammaraja as the most warlike king on the coast. The Arakanese king he explained was the only local ruler who defied Mughal rule and was in fact continually at war with the imperialists. He suggested that the Arakanese kept an 5 ARAKAN AND BENGAL STEPHAN VAN GALEN

ARAKAN CONFERENCE BANGKOK 9 MARCH 2013 army of 500 frigates and approximately 80,000 men ready for their wars in south-eastern Bengal.33 These observations are confirmed by Manrique who describes how between 1622 and 1629 no Augustinian monks had traveled from Hugli to Dianga because of the incessant warfare in south-eastern Bengal.34 In 1629 for example an Arakanese fleet sailed up the river Meghna. The fleet under the command of the Portuguese captain Diogo de S plundered villages only a few miles from Dhaka. Manrique described how the crews of the jelias: reaped a rich and plentiful booty. Among this they captured a lovely Mogol lady of rank who was escaping with her daughter and mother-in-law in a covered cart, accompanied by a few men on horseback and some servants. 35 The invaders managed to leave the vicinity of Dhaka without ever being challenged by the Mughal fleet, which had its base at Dhaka. The Mughal lady captured by the Portuguese later explained to Manrique she had been married to a Mirza who held the rank of a commander of two thousand horses. This affair, according to Manrique, sufficiently enraged Shah Jahan to order the destruction of Hugli as the Portuguese from Hugli had strong connections with Portuguese communities in Arakan and Chittagong.36 Although there were much more motives behind the removal of the Portuguese from Hugli in 1632, this event aptly illustrates how ineffective Mughal control over south-eastern Bengal was at the beginning of Shah Jahans reign. The Arakanese controlled eastern Bengal and could claim it as their domain. As a result the Mughals withdrew their capital from Dhaka to Rajmahal in the late 1630s. In Rajmahal they were safe from Arakanese attacks. It is also significant that in 1665 the Portuguese operating under the control of the Arakanese in Chittagong, after they went over to the Mughal side, were able to show complete records of taxes collected from Bengal dating back to c. 1625. These records Talish explained were a comprehensive overview of the division of the income of Bengal, specified on a village by village basis. 37 The existence of these records proves that the Arakanese had been able to control large parts of south-eastern Bengal following the wars of Sirisudhammaraja. Talish interestingly describes the Portuguese as having regarded south-eastern Bengal, or the tract from Dhaka to Chittagong, as their jagir.38 It has of course to be remembered that these Portuguese formed part of the Mrauk U kingdom and were in fact employed by the Arakanese kings. The Arakanese were thus able to levy taxes and extract land revenue from their Bengal domains from the middle of the 1620s. This strongly contradicts conventional views of Mughal rule in Bengal that regard the initial 6 ARAKAN AND BENGAL STEPHAN VAN GALEN

ARAKAN CONFERENCE BANGKOK 9 MARCH 2013 establishment of the Mughal capital of Bengal at Dhaka as the start of Mughal control over all of Bengal. Eatons claim that soon after Islam Khans arrival in Bengal, the Mughals succeeded in annihilating or winning over all major chiefs entrenched in the countryside since the time of the sultans should therefore be revised.39 But the reign of Sirisudhammaraja also saw the emergence of a conflict within Arakan itself. In 1628 one of the most important noblemen in Arakan, the Laungkrak ca, revolted against the king. Laungkrak was a former royal capital and situated close to Mrauk U. A Dutch trading mission arriving in Arakan on 24 July 1628 reported that shortly before their arrival the Laungkrak ca had tried to overthrow the king and had attempted to crown himself king. 40 Following the attempted coup d'tat a civil war ensued in which a large number of noblemen were killed. It was estimated that of the Laungkrak cas people three to four thousand had died. The Dutch merchants described that also during their stay in Arakan people belonging to the rebellious faction were killed. The king apparently still felt that his position was not secure. The Laungkrak ca had escaped the killings and operated in a region outside the control of Sirisudhammaraja. The arrival of the VOC mission aroused suspicion as relations between the VOC and the Laungkrak ca had always been extremely friendly. The revolt of the Laungkrak ca thus temporarily prevented Sirisudhammaraja to execute any plans he might have had towards further territorial expansion.

But in 1635, following the great famine of 1631-1634, Arakans power had reached its zenith.41 Arakanese fleets operated freely from Bengal to Tenasserim.42 The same year Sirisudhammarajas official coronation finally took place. On this slide a royal procession in Mrauk U. The expansion of Arakanese influence prompted the Burmese and the Mughals to retract their (provincial) capitals further inland. The coronation of Sirisudhammaraja as described by Manrique in his Itinerario is a clear indication of the new self-confidence of the Arakanese monarchy. Manrique claimed that the coronation itself was part of Sirisudhammarajas ambition to obtain the vast empires of Delhi, Pegu, and Siam.43 Sirisudhammarajas military achievements and foreign policy seem to confirm the ambitious goals of this king. Although the conquest of these mighty empires might seem several bridges too far, Sirisudhammaraja by military means did earn the respect of his imperial neighbours. This newly-won self-confidence of the Arakanese can also be gleaned from the coins issued at the coronation. While the first coins Sirisudhammaraja struck when he came to power in 1622 7 ARAKAN AND BENGAL STEPHAN VAN GALEN

ARAKAN CONFERENCE BANGKOK 9 MARCH 2013 were still firmly rooted in the tradition of his predecessors, his coin of 1635 is a clear statement of Arakanese supremacy in the region. Earlier Mrauk U coins had trilingual texts in Arakanese script, Persian and Bengali. These coins, apart from the Arakanese titles of the king, also provided Muslim titles.44 The 1635 coin is monolingual, in Arakanese only. The title of the king is given in Pali in Arakanese script a clear statement of a king confident of his power.45 In describing the rise of the Mrauk U kingdom my central theme was the Ninety Years War (c. 1574-1666) between the Arakanese and the Mughals over south-eastern Bengal. Now I will review some aspects of the economic history of the Arakan-Bengal continuum that help us to understand the underlying dynamics of the expansion and the subsequent fragmentation of the Arakanese kingdom at the end of the seventeenth century. It will be argued that the control over south-eastern Bengal, the economic centre of Bengal from the middle of the sixteenth to the middle of the seventeenth century, was the cork on which the Arakanese kingdom thrived. A comparison will be made of the effects of incomes from trade and tax revenues from Bengal on the rise and decline of the Mrauk U kingdom. It has until now been assumed that revenues from trade were essential for the rise to power of the Arakanese kings. Maurice Collis, San Shwe Bu, D.G.E. Hall, Michael Charney and Jacques Leider all have suggested that trade provided the Arakanese kings with revenues that enabled them to first expand and later consolidate their hold over other local centres in the Arakanese littoral and which were also an important instrument in the expansion of the Arakanese kingdom.46 These assumptions have been based on a more or less superficial understanding of the mechanisms of Arakanese trade and taxation. In fact when viewed in terms of the commerce in the Bay of Bengal as a whole Arakanese trade was a rather limited affair. To be able to assess the importance of revenues from trade vis--vis land revenues form Bengal I will provide a more detailed analysis of the development of trade and taxation in Arakan during the seventeenth century. When we compare Mrauk U and Chittagong in a regional context the port of Chittagong was far more successful in attracting long-distance trade and was of strategic importance for anyone wishing to control south-eastern Bengal. The possession of Chittagong and its revenues was in this respect extremely important for the Mrauk U kings if they wanted to keep their advantage in the redistributive networks that formed the Arakanese state. Revenues from south-eastern Bengal flowed directly into the hands of the Mrauk U rulers enabling them to sustain large armies and to build strong alliances. 8 ARAKAN AND BENGAL STEPHAN VAN GALEN

ARAKAN CONFERENCE BANGKOK 9 MARCH 2013

The central role of Chittagong in Bay of Bengal trade was illustrated when in 1608 the VOC sent a trading mission to Arakan to discover the trade of Bengal. The Arakanese king Man Raja-kri offered the harbour of Dianga near Chittagong to the VOC. Man Raja-kri suggested the company should make a fortress at Dianga for the protection of merchants. On this slide you can see the translation of the royal letter with a drawing of the seal of the king. In 1616 after the Arakanese king Man Khamaung had removed Sebastio Gonalves Tibao from Sandwip he told the Dutch company how during the early years of the seventeenth century Manuel de Mattos had succeeded in generating a tax revenue at Dianga of 20,000 Tanka.47 The Arakanese kings thus hoped to employ Dutch naval strength to protect trade in the Arakan-Bengal continuum and to enhance their own income from tax. Arakanese promises of a profitable trade in this part of the Bay of Bengal prompted several investigations by the Dutch company into the nature of trade in the Bay of Bengal. Two special reports concerning this trade were eventually produced, one written in 1608, the other in 1614.48 Both reports provide an overview of the trade in this part of the Indian Ocean during the early seventeenth century. The Sripur area was in fact the economic heart of Bengal. It is striking that early in the seventeenth century the VOC identified Chittagong as the port which they wanted to use as a base for trading with Bengal and places as far into the interior of India such as Agra and Lahore. Surprising as this may seem, accustomed as historians are today to the success of European trading companies operating from their factories on the river Hugli in the eighteenth century, it is certainly an anachronism to identify the Hugli as the centre of the Bengal economy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.49 The superiority of south-eastern Bengal ports over those situated on the Hugli is clearly expressed by Johan van Leenen in his report of the survey of the Bay of Bengal from the Kaladan to the Brahmaputra in 1666. Van Leenen concluded that Dhaka and Chittagong were far better situated to exploit the commerce of Bengal than the ports on the river Hugli. He observed that Dhaka possessed much better inland connections than the ports on the western branches of the Ganges and was also much easier reached from the Bay of Bengal from a port such as Chittagong.50 The only reason in fact that forced the European trading companies, and of course indigenous merchants as well, to settle at the Hugli was the incessant warfare between Arakan and the Mughals over southeastern Bengal, a war that was fought to control the economic centre of sixteenth and seventeenth century Bengal. The settlement of the European companies on the Hugli was thus a necessity and not because this was from the very beginning near the economic centre of Bengal. The Ninety Years war between Arakan and Bengal prohibited those traders from settling at the most convenient spot, Chittagong. 9 ARAKAN AND BENGAL STEPHAN VAN GALEN

ARAKAN CONFERENCE BANGKOK 9 MARCH 2013

I will argue that Arakan itself only permitted a small scale trade, augmented by the slave trade, but put crudely this was just another kind of revenue from Bengal. The rice trade was the central pillar of the Arakanese economy and will be discussed first. The extremely low price of rice in Arakan should, apart from the favourable climate, also be attributed to the use of slave labour.

The development of the Arakanese trade during the 17th century From the reign of king Man Raja in 1518 Arakanese kings are seen to actively promote commerce. Man Raja in 1518 sent a letter to the king of Portugal inviting Portuguese traders to Arakan and offering them security.51 It is however only from the reign of king Man Pa in the middle of the sixteenth century that Arakanese chronicles mention the arrival of large numbers of merchants in Arakan. Man Pa is credited with the creation of a class of guards for the protection of foreign traders and digging tanks with fresh water for the use of these merchants.52 With arrival of groups of Portuguese merchants in the Bay of Bengal in the second half of the sixteenth century more information on Arakanese trade becomes available. From the first decades of the seventeenth century the VOC encountered fierce competition from Muslim merchants from Coromandel in Arakan. During the whole seventeenth century traders from Coromandel would be the only noticeable group of foreign merchants in Mrauk U apart from the VOC and private Portuguese and Dutch traders. The competition of the Coromandel merchants forced the VOC to abandon the idea of importing high quality cloth from Coromandel in Arakan.53 The huge profits of the elephant trade enabled the Coromandel merchants to sell, if needed, their goods at considerable losses in Arakan.54 The trade between Coromandel and Arakan remained firmly in the hands of Indian merchants throughout the seventeenth century.55 Although Arakanese kings from the early sixteenth century actively fostered trade to enhance their own incomes, Sirisudhammaraja is the first Arakanese king known to have operated as a merchant himself. To the marked surprise of the Dutch this king started sending his own ships to Coromandel in 1628.56 Almost a decade later also the chief queen of Sirisudhammaraja, Nat Shin May, is reported to have sent her own ships to Coromandel.57 The trade of the king and queen mainly centred on the sale of elephants to Coromandel. It seems the king received elephants as a form of taxation in kind or tribute from tribes living in the hills and sold them either via his own agents in Coromandel or to foreign merchants in Arakan who would export them to Coromandel.58 The elephant trade would be one of the mainstays of the Arakan10 ARAKAN AND BENGAL STEPHAN VAN GALEN

ARAKAN CONFERENCE BANGKOK 9 MARCH 2013 Coromandel trade during the seventeenth century. Elephants would sell against high prices in Coromandel, giving profits of between 100 to 500%.59 An animal bought in Arakan for 1,300 or 1,400 Tanka would in Coromandel fetch the same amount in Pagodas, i.e. five times as much.60 On this slide an example of a royal letter on the elephant trade from Candasudharmaraja to a merchant in Madras. The goods brought from across the Bay of Bengal were bought in Arakan by petty traders. In Arakan the VOC had to sell its goods in small quantities. Adam van der Mandere remarked that due to the absence of large merchants he had to sell goods in small portions of between 4 and 10 Tanka. Van der Mandere observed that there were no merchants with more than 200 Tanka in cash in Arakan. Rice trade Data on the mainstay of the seventeenth century Arakanese economy, the rice trade, can only be found in the archives of the VOC. The description below of this important sector of the Arakanese economy is therefore heavily influenced by Dutch perspectives. In 1608 Pieter Willems headed the first Dutch trading mission to Arakan and in September 1627 the first Arakanese embassy arrived in Batavia. There the Arakanese noticed that the Dutch settlement was almost stricken by a great famine after the Sultan of Mataram had laid siege to the city.61 The importance of Arakanese rice for the survival of Batavia was thus immediately impressed upon the envoys. The Dutch entertained mixed feelings about the Arakanese presence in Batavia. On the one hand the diplomatic exchanges would provide the much needed rice to feed the citys populace; on the other hand the ambassadors would return with the knowledge of exactly how crucial Arakanese rice was for the survival of Batavia and how cheap it was in comparison with Batavian prices. The marked price difference was indeed sufficient reason to discourage the sending of Arakanese envoys to Batavia.62 In February 1636 Batavia received more than 400.000 kg rice, half of which was immediately sent on to Ambon and the Banda islands. The amount of rice from Arakan would feed a population of approximately 3,000 persons for one year. The next year almost 700.000 kg rice, enough to feed circa 5,000 people a whole year came from Arakan to Batavia.63 Batavia had in 1632 8,060 inhabitants. From these figures the crucial importance of Arakanese rice for the survival of Batavia and the Spice Islands can easily be understood. It appears that the price of rice in Arakan had remained stable throughout the seventeenth century at between 2 and 3 Tanka for 200 kg during normal years. Bad harvests would of course occasionally result in a temporary sharp increase in prices. The high prices following the resettlement program of the 1640s combined with bad harvests remain the only exception 11 ARAKAN AND BENGAL STEPHAN VAN GALEN

ARAKAN CONFERENCE BANGKOK 9 MARCH 2013 to this rule. The mass deportation initiated by Narapati-kri in 1643 resulted in sharp increases in the price of rice and almost everything else. Rice prices more than doubled during these years and resulted in famine. High rice prices continued at least until 1647. It is reasonable to assume that they continued well into the early years of Candasudhammarajas reign. The temporary cessation of taxation during the first three years of Candasudhammarajas reign from 1652 to 1655 suggests that during these years extraordinary measures were needed to revive the Arakanese economy. After 1684 the peace with Banten enabled the VOC to obtain rice from sources closer to Batavia. This meant Arakanese rice was not needed anymore to secure a steady food supply for Batavia and the Spice Islands.

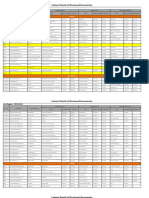

Income from land revenue and trade compared Now that we have briefly touched the functioning and development of trade, it is time to assess the relative importance of the control over south-eastern Bengal in terms of land revenue with Arakanese incomes from trade. The question is essentially how important a source of revenue were Arakans Bengal dominions in comparison to the income from trade. The Mughal estimates of the Bengal revenues provide a clear illustration of the wealth of south-eastern Bengal.64 The first revenue settlement of Bengal made by Todar Mal in 1582 shows the areas which we now know to have been the battlefield between the Arakanese and the Mughals yielded an estimated 2 million Rupees, or about 30% of the Bengal revenues. This would include sarkars under Arakanese control like Hijli, Jessore, Bakla, the Dhaka area, and of course Chittagong. Chittagong alone accounted for 300.000 Rupees, while the Dhaka area was rated at 1.000.000 Rupees.65 The second revenue settlement of Bengal is the 1658 assessment made on orders of Shah Shuja.66 If we are to follow Eaton, who calculated on average a 100% increase in the revenues of south-eastern Bengal from 1582 to 1658, the south-eastern Bengal revenues would have grown to c. 5 million Rupees in the middle of the seventeenth century.67 Although the underlying figures are sometimes difficult to interpret it is clear that south-eastern Bengal was an important economic centre already in the late sixteenth century, certainly worth the effort of conquering.. In the 1658 settlement several new sarkars are added to Todar Mals list, most of them are most likely recently conquered areas. It is therefore wrong to assume, as Eaton does, that the increase in Bengal revenues should be attributed primarily to economic growth. Mughal revenues saw spectacular increases in the mid-seventeenth century that were at least partly the immediate result of conquest. In fact these newly conquered territories had already from the sixteenth century been part of the economic heart of Bengal.68 It would be wrong to assume that the majority of these revenues had all flowed into Arakanese coffers during the first half of the seventeenth century. But it is also wrong to 12 ARAKAN AND BENGAL STEPHAN VAN GALEN

ARAKAN CONFERENCE BANGKOK 9 MARCH 2013 assume that because areas such as Chittagong were included in Mughal revenue accounts since 1582, these areas were actually controlled by the Mughals. On the basis of the reconstruction of the Arakanese-Mughal conflict in my dissertation we can however conclude that a large part of south-eastern Bengal revenues flowed into Arakanese coffers before the middle of the seventeenth century. This corroborates Van der Helms mid-seventeenth century statements quoted earlier where he argued that the income from Bengal taxes was the most important source of revenue for the Arakanese treasury. Earlier in the seventeenth century the Dutch chief on the Coromandel coast wrote to the VOCs governor-general in Batavia that Bengal was of considerable economic importance to the Arakanese.69 British and Mughal revenue settlements of the Chittagong area clearly point to the fact that regular land revenue collection was an important element of Arakanese control over this part of Bengal.70 The fact that when the British took control over Chittagong the land revenue administration was still based on Arakanese standards provides evidence that revenue extraction from Bengal was organized along the same lines as it was in Arakan itself. In Chittagong land was for instance measured in Maghi kani. Land surveys were made according to Arakanese methods, no maps were used, but the measurements were recorded in a field book. The Mughals moreover used the Arakanese era in fiscal matters.71 This would lead to the conclusion that the Mughals probably ratified existing estates, which had already been measured by the Arakanese. This is confirmed by the fact that the majority of local zamindars reportedly settled in Chittagong from the middle of the sixteenth century when the area was first occupied by the Arakanese.72 From this evidence we may conclude that regular land rent collection formed part and parcel of Arakanese administration in south-eastern Bengal. As quoted earlier, Talish in the Fatiyyah-i-ibriyyah stated that regular accounts of the Bengal revenue with regards to the sarkars to the northwest of Chittagong were kept by the Portuguese operating under Arakanese control from Chittagong.73 The question that we should ask ourselves now is what share of official income depended on agrarian management and what share was derived from trade. Taxes on trade in Arakan should be estimated at most at 10%. Of this tax 4% went to the kings officials and 6% directly to the king.74 Between 1636 and 1644 VOC return cargoes from Arakan were valued at between 12,000 and 31,000 guilders a year.75 This suggests that tax incomes from trade with the Dutch probably amounted to between 800 and 2,500 Tanka per annum. The Dutch certainly were the largest traders in Arakan accounting for the majority of the cargo entering and leaving the country. If we speculate, we could assume that tax on trade levied on all other traders would 13 ARAKAN AND BENGAL STEPHAN VAN GALEN

ARAKAN CONFERENCE BANGKOK 9 MARCH 2013 probably not amount to much more than taxes levied on VOC trade as a whole. This would give a tentative figure for income from trade of c. 5,000 Tanka each year. Traders of course also brought gifts, which can also be considered as royal revenues from trade. Taken together taxes and gifts would probably not amount to more than 10,000 Tanka on a yearly basis. Tax incomes from trade in Chittagong are difficult to assess. For the early seventeenth century we know that in 1616 the Arakanese king Man Khamaung told the Dutch that during the early years of the seventeenth century Manuel de Mattos had succeeded in generating tax revenue at Dianga of 20,000 Tanka and I suggest that revenues would not have grown spectacularly during the rest of the seventeenth century. If we are now to compare royal incomes from trade with those from land revenues this means income from trade paled into insignificance, even if only Chittagonian land revenue, which is estimated at between 250.000 and 500.000 Rupees is considered, which as was argued earlier certainly does no justice to the extent of Arakanese control over Bengal. If we add income from the slave trade as another form of revenues the importance of Bengal for Arakan can hardly by underestimated. Conclusion The establishment of Arakanese control over Chittagong from the late sixteenth century onwards provided the Arakanese kings with a significant source of revenue which enabled them to expand Arakanese royal power across the Arakan-Bengal continuum. Arakan thrived because the Arakanese kings were able to exploit the riches of Bengal from the strategic fortress at Chittagong. These riches consisted of its land revenue, taxes from trade and human resources. The withering of Arakanese control in south-eastern Bengal after 1638 meant that the income from land revenues decreased. From the mid 1640s, the Arakanese economy declined and collapsed after the loss of Chittagong in 1666. The large scale trade in slaves slowly died out during this period. VOC demand for Arakanese rice almost disappeared when the Dutch found other more easily accessible sources. The departure of the VOC from Arakan had its impact on other merchants; larger merchants from Coromandel followed the Dutch example and stopped their businesses in Arakan. With the disappearance of the Bengal revenues and the departure of the VOC the Arakanese markets dried up. Arakanese royal power that had depended upon the redistribution of the considerable wealth generated by the control over Bengal and taxes from trade was now challenged from within. The country subsequently was torn apart by civil war at the end of the seventeenth century. This brings me to the end of my talk to you, I have tried to give a brief glimpse of Arakanese history during the rule of king Sirisudhammaraja and the importance of control over Bengal 14 ARAKAN AND BENGAL STEPHAN VAN GALEN

ARAKAN CONFERENCE BANGKOK 9 MARCH 2013 for the expansion of the Arakanese state in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. If you want to learn more you can download my book from the library of Leiden University, it is freely available.

Thank you.

Stephan van Galen.

15 ARAKAN AND BENGAL STEPHAN VAN GALEN

In this paper Arakan will be used to refer to the area which is in Arakanese known as Rakhaing or Rakhine. Arakan is a corruption of Rakhaing, used in western sources since the early sixteenth century. The Arakanese traditionally derive this name from the Pali Rakkha, or the Sanskrit Raksasa synonymous with the Burmese Bilu or Ogre. The Arakanese are by the Burmese also referred to as Myammagye or Great Burmese, the Burmese tracing their decent from the Arakanese. BL OIOC, Mss. Eur. C 13, Copy of a journal of progress and observations during the continuance of the deputation from Bengal to Ava in 1795 in the dominions of the Barma monarch by dr. F. Buchanan, fols. 172, 176-177; Pamela Gutman, Ancient Arakan: with special reference to its cultural history between the 5th and 11th centuries (PhD thesis: Australian National University, 1977), pp. 1-3. 2 As the exact date of Di Contis visit to Arakan is not known it is possible that he visited Arakan at a time when Laungkrak was the capital city. Mrauk U was founded in 1430. 3 An Account of the Burman Empire and the Kingdom of Assam. Compiled from the works and M.S. documents of the following most eminent authors and public functionaries, viz. Hamilton, Symes, Canning, Cox, Leyden, F. Buchanan, Morgan, Towers, Elmore, Wade, Turner, Sisson, Elliot, &c, &c. (Calcutta, 1839), pp. 84-86 . 4 For various legendary explanations of the name Mrauk U see San Baw U, My rambles among the ruins of the golden city of Myauk-u, Journal of the Burma Research Society, 11.3 (1921), pp. 163-169, ch 1-3; 13.2 (1923), pp. 99-105, ch. 4-5; 16.1 (1926), pp. 36-42, ch. 6-7; 23.1 (1933), pp. 13-19, ch. 9; ch 4, pp. 99-103. Leider, Taxation, p. 74-75. 5 Exiled in 1406 the Laungkrak king Naramitlha returned to Arakan taking the name of Man Co Mwan. Leider On Arakanese territorial expansion, pp. 128-129 ; Leider, Le royaume dArakan, pp. 58-64. 6 Although the foundation myths purport to describe the early fifteenth century, there are good reasons to assume that the various chronicle traditions actually refer to a much later period of c. the seventeenth century when the Mughals had become a potentially serious threat to Arakanese rule in south-eastern Bengal. Leider has pointed to the abundant use of anachronisms and the frequent erroneous references to Indian or Bengal rulers not contemporary to Man Co Mwan. Jalal ud-Din is also not named as such, but reference is made to the Bengal sultan. See Leider, Le royaume dArakan, pp. 60-62 and Leider, These Buddhist kings with Muslim names. S.E. Hussain, The Bengal Sultanate. Politics, Economy and Coins (AD 1205-1576) (Delhi: Manohar, 2003) pp. 111-113. 7 Hussain, The Bengal Sultanate, p. 113. 8 Vesali was an early Arakanese city located in the Kaladan valley. 9 Coins struck in east Bengal were for example exact copies of Vesali coins. Kyaw Minn Htin, Historical Geography and Urbanization in Ancient Arakan, Myanmar. The archaeological landscape of the old capitals to AD 1400, 2nd Singapore Graduate Forum on Southeast Asia Studies (Asia Research Institute / National University of Singapore, 26-27 July 2007), pp. 2-6. S.M. Ali, Chandra kings of Pattikera and Arakan, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Pakistan 6 (1961), pp. 267 274. 10 The Arakanese name of this king is Man Kha ri, but he is best known by his Muslim name. Leider, These Buddhist kings with Muslim names, p. 207. 11 Leider, Le royaume dArakan, pp. 66-68. 12 Leider, Le royaume dArakan, pp. 70-74. 13 See Bibliothque national Paris Mss. Anglais 26. Extrait dune chronique Arakanaise. Kindly provided to the author by Jacques Leider. 14 Leider, Le royaume dArakan, pp. 76-77. 15 Leider, Le royaume dArakan, p. 166. 16 See for instance the story of king Datha Raja who allegedly resettled rebellious Bengalis in the Arakan littoral in 1156. Summary of the work done by Maung San Shwe Bu, Honorary Archaeological officer for Arakan, Report of the Superintendent Archaeological Survey Burma (Rangoon, 1919), pp. 55-57. 17 Leider, Le royaume dArakan, p. 138. 18 Perhaps the Arakanese regarded Magadha as their charter state in a sense as suggested by V. Lieberman, Strange parallels. Southeast Asia in global context, c. 800-1830. Volume 1: Integration on the mainland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), pp. 77-78; A. Sharif, On Arakan and the Arakanese in A.B.M. Habibullah, Nalini Kanta Bhattasali commemoration volume. Essays on archaeology, art, history, literature and philosophy of the Orient, dedicated to the memory of dr. Nalini Kanta Bhattasali [1888-1947 A.D.] (Dhaka: Dhaka Museum, 1966), pp. 351-360. Cf. S.C. Das, A note on the antiquity of Chittagong, compiled from the Tibetan works Pagsam Jon-Zan of Sumpa Khan-po and Kahbab Dun-dan of Lama Tara-Natha, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 67 (1898), pp. 20-28. 19 For instance Husain Shah by the Arakanese king Man Khamaung. Leider, These Buddhist kings with Muslim names, p. 211. 20 Sarkar, History of Bengal, pp. 305-311; Nathan, Baharistan-i-Ghaybi, pp. 2:689-694, 711. 21 Nathan, Baharistan-i-Ghaybi, p.2:711. 22 National Archives of The Netherlands (NA) VOC 1083 Letter from Hendrick Lambrechts from the yacht Medenblick at anchor before Urittaung (Arakan) dated 5 December 1623, fol. 188-190. 23 Ibidem.

24

Sarkar, History of Bengal, p. 312. The VOC bought in c. December 1624 400 slaves in Arakan. These slaves must have been the result of the raid described by Nathan. In 1623 the VOC was not allowed to buy slaves who had been in Arakan for more than a year. NA VOC 1084 Letter from Marten IJsbrantsz from Pulicat to the chamber Amsterdam dated 28 April 1625, fol. 167r and .N. A. VOC 1083 Letter from Hendrick Lambrechts from the yacht Medemblick at anchor before Urittaung (Arakan) dated 5 December 1623, fol. 188-190. For the functioning of the slave trade see Chapter 8 of this dissertation. 25 NA VOC 1087 Report on Arakan by Jan van der Burch dated 5 December 1625, fol. 170r-172v. The report does not mention the sack of Dhaka. The capture of Sripur is mentioned as the main result. 26 Sarkar, History of Bengal, p. 313. 27 NA VOC 1094, fol. 245v-246r Letter from Marten Ysbrantsz., dated Pulicat 4 June 1626. 28 Talish, Fatiyyah-i-ibriyyah, fol. 177b erroneously has 1033 AH (1623 AD) as the end date of Khanahzad Khans subahdarship in Bengal, this must be a mistake as in 1623 Ibrahim Khan was still governor. 29 NA VOC 1094, fol. 245v-246r. In a letter from Pulicat dated 4 June 1626 Marten IJsbrantsz. reported that the king of Arakan claimed a large victory in Bengal this year. 30 Talish, Fatiyyah-i-ibriyyah , fol. 155b. 31 Letter from Coen dated 9 November 1629. Alle maenden comender schier nieuwe gouverneurs, die niets trachten als te schrobben en te scheeren. Colenbrander, Coen. Bescheiden omtrent zijn bedrijf, p. 5:29. 32 Letter from Marten IJsbrantsz to Coen, dated Pulicat 30 July 1628. In Bengalen is voor ons niets te doen aangesien dit lant nogh geheel en al in oorlogh staat. Colenbrander, Coen. Bescheiden omtrent zijn bedrijf, p. 7:1350-1352. 33 NA Secrete Casse der Oostindische Compagnie, Archief der Staten Generaal 12581.13 volgnummer in inventaris 1254 Rapport van den gewesenen gouverneur Carpentier van de gelentheijt der saecken in d'Oost Indien ten tijde van sijn affscheijt aen haer hoog mogenden overgelevert den 29 september 1628 n.f. headings Arakan and Bengalen. 34 Manrique, Itinerario, p. 1:84 quoted in Leider, Le royaume dArakan, p. 251. 35 Manrique, Itinerario, pp. 2:316-312. 36 Manrique, Itinerario, pp. 2:316-312. See also Van Veen, Decay or defeat?, p.215. 37 Talish, Fatiyyah-i-ibriyyah , fol. 152a-152b. See also J. N. Sarkar, The Feringi pirates of Chatgaon, 1665 AD, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 3.6 (1907), p. 425. 38 Talish, Fatiyyah-i-ibriyyah , fol. 107b-108a, 123b, 139a-139b. 39 See for such a view Eaton, Rise of Islam, pp. 157 and also pp. 137-138, 149. 40 NA VOC 1096 Letter from Martinus Lowijsen and Roeloff Cornelisz. Kan to the governor Marten IJsbrantsz, dated Arakan 21 October 1628, fol. 136-137. 41 Leider, Le royaume dArakan, p. 251 Lapoge de la puissance militaire (1622-1652). 42 In October 1634 representatives of the English East India Company in Masulipatnam requested their Board of Directors: to sent two small pinnaces to remain on [the coast of Bengal] , of 80 to 120 tons to draw little water and to carry 12 or 14 guns. The Dutch never [are] without three or four of these vessels, which trade from port to port or are employed as men of war, never idle, and clear all their great charges on this coast. There is no thought of trade into the Bay without them, the greater ships riding so far from the shore, and the King of Arracan's jellines, or small boats of war, ever scouting between them, so as neither goods nor provisions can be brought off without pinnaces of some defence, which may go up the rivers without fear. W.N. Sainsbury ed., Calendar of State Papers. Colonial series, East Indies 1513-1634 5 vols. (London, 18621892), pp. 4:583-589. 43 Manrique, Itinerario, p. 1:351. The description of the coronation takes up the chapters 31 to 35. 44 For instance, Sikandar Shah (Man Phalaung) or Husain Shah (Man Khamaung). Leider, These Buddhist kings with Muslim names, pp. 210-211. 45 M. Robinson and L.A. Shaw, Coins and Banknotes of Burma (Manchester: Lancashire and Cheshire Numismatic Society, 1980), pp. 44-65 and esp. pp. 55-56 46 Charney, Rise of a mainland trading state, pp. 1-4; Leider, Le royaume dArakan, pp. 417-418; Maurice Collis and San Shwe Bu, Arakans place in the civilization of the Bay: a study of coinage and foreign relations, Journal of the Burma Research Society 15.1 (1925), pp.. 34-51; Hall, Studies in Dutch relations, pp. 1-31. 47 NA VOC 1061, Letter from Cortenhoeff to the chamber Amsterdam, dated Masulipatnam 25 April 1616, fol. 192r. 48 NA VOC 1055 n.f. Report on the Bay of Bengal and Arakan by Pieter Willemsz., dated Masulipatnam 25 May 1608 printed as Pieter Willemsz, Informatie van de Bochte van Bengala en de Arracan gedaen door Pieter Willemss. in Masulipatnam desen 25 Maij Anno 1608, J.K.J. de Jonge, De Opkomst van het Nederlandsch Gezag in Oost-Indi (15951610) 16 vols. (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1862-1909), pp. 3:287-291. and NA VOC 1059 Cortenhoeff, Short note on Diango and other places in Bengal, n.d. [1614], fol. 107. 49 The Hugli was of course the best place to access the Bihar market for saltpetre and opium. 50 NA VOC 1264, fol. 328-336 Report of Johan van Leenen, commander of the ships Landsmeer and Purmerland in aid of the king of Hindostan in his war against Arakan, darted Batavia 2 July 1667., fol. 332v. Langs dit gewenste vaerwater, dan Edele heeren, connen de goederen en coopmanz. van de Comp. seer bequaemel. naer Decaa en Ouglyse Ganges af en aan

gevoert werden, ende verseeckeren wy Ueds dat sulckx niet alleen vry voorspoediger, maer oock met minder moeyte en gevaer als langs den wegh der sout barcken steets sal connen geschieden ende om weclke redenen benevens alle de vooraangehaelde ick oordeelen moet, niet als seer wel te hebben gedaen, dat den wech van Decaa naer Ougly door see ben gevaeren, ende alsoo sal nu volgens ueds goed concept begrepen in voorgemelt. haer eds papieren het middel syn uytgevonden om niet allen den Tessindiansen zuycker, die met weinigh oncosten een wech van 2 a 3 dagen voor stroom to Decca int laetste van september can gebracht werden, te bevryden, van soo veel molesten pericul en swaere ongelden als men jaerlykcx int afbrenghen van deselve naer Ougly siet geschieden, maer oock behalven dat wy hebben doen sien hoe de vaert van Arracan op Setigam met groot ende cleyn vaertuyg soo wel is te gebruicken, soo sal de negotie tot Decca connen vry syn behalven van de moeilyckheden die dese onderworpen is, noch van soo veele oncosten die nu met t af en aanbrengen vande goederen op de binnenwateren moeten gedaen werden. 51 Bouchon, Voyage, pp. 362-363. 52 Leider, Le royaume dArakan, pp. 429. 53 NA VOC 1084, fol. 166-168 Letter from Marten IJsbrantsz to the chamber Amsterdam, dated Pulicat 28 April 1625., fol. 167r. 54 NA VOC 1134, fol. 183-189 Letter from Arent van der Helm to Batavia, dated Arakan 20 December 1640. 55 Haji Baba operated from Arakan at least from 1608 to 1623. NA VOC 1055 Letters and papers from Atjeh n.f. nr. 1 Letter from Jan Gerritsz Ruyll on board the ship of Moluque Tujar to the next VOC representative arriving in Arakan, dated Arakan 27 March 1608; NA VOC 1065, fol. 114-115 Letter from Andreas Crieck to Coromandel, dated Arakan 12 February 1615; NA VOC 1083, fol. 188-190 Letter from Hendrik Lambrechts to Coromandel, dated Arakan 5 December 1623. 56 Colenbrander, Coen. Bescheiden omtrent zijn bedrijf, pp. 7:1350-1352 Letter from Marten IJsbrantsz to Coen, dated Pulicat 30 July 1628. Subrahmanyam, The political economy of commerce. Southern India 1500-1650 (Cambridge, 1990) p. 307. 57 NA VOC 1125, fol. 477-485 Letter from Adam van der Mandere to Batavia, dated Arakan 10 January 1637. NA VOC 1126, fol. 291-297 Letter from Adam van der Mandere to Batavia, dated November 1638. 58 Colenbrander, Coen. Bescheiden omtrent zijn bedrijf, pp 7:1435-1438 Letter from Marten IJsbrantsz to Coen, dated Masulipatnam 24 September 1628. Dagh-register 1641-1642, p. 145 entry for 1 May 1642 containing a letter from Lunnenburgh to Batavia, dated Arakan 2 March 1642. 59 NA VOC 1134, fol. 183-189 Letter from Arent van der Helm to Batavia, dated Arakan 20 December 1640. 60 The Tanka valued at 24 stivers and the Pagoda at 120 stivers. Pagoda value from Dijk, Seventeenth century Burma 2.135. 61 Colenbrander, Coen. Bescheiden omtrent zijn bedrijf, pp 5:295-296 Letter from Coen to Marten IJsbrantsz., dated Batavia 14 June 1628; Colenbrander, Coen. Bescheiden omtrent zijn bedrijf, pp 5:306-309 Instruction from Coen for Martinus Lowijszen and council with the fluijt Edam destined for Arakan, dated Batavia 15 June 1628. Mataram besieged Batavia in 1628 and 1629. Coen died during the siege as a result of disease. H.E. Niemeijer, Batavia. Een koloniale samenleving in de 17de eeuw (Amersfoort: Balans, 2005), pp. 24-25; Raben, Batavia and Colombo, p. 12. 62 Colenbrander, Coen. Bescheiden omtrent zijn bedrijf, pp 5:451-453 Letter from Coen to president Vischer in Banda, dated Batavia 25 January 1629. 63 The last was set to 3,000 pounds when calculating rice shipments. The World Food Programme of the United Nations recons 144 kilo rice per person per annum as a minimum. 64 The Mughals clearly used existing accounts and made no settlement of their own. W. H. Moreland, Akbars land revenue arrangements in Bengal, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (1926), pp. 43-56. 65 W. K. Firminger ed., The 5th report from the Select Committee of the House of Commons in the affairs of the East India Company: dated 28th July, 1812 3 vols.( Calcutta: R. Cambray, 1917-1918), pp. 2:176-188. 66 F.D. Ascoli, Early Revenue History of Bengal and the fifth report, 1812 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1917), pp. 22-25. 67 Eaton, Rise of Islam, p. 199; Firminger, The 5th report, pp. 176-188; A. Karim, Murshid Quli Khan and his times (Dhaka: Asiatic Society of Pakistan, 1963), pp. 74-81. 68 Eaton, The rise of Islam, pp. 198-203. 69 NA VOC 1057, fol. 127-140 Letter from Wemmer van Berchem to Pieter Both in Batavia, dated Masulipatnam 16 August 1614, fol. 129v-130. 70 C.H.G. Allen, Final report of the survey and settlement of the district of Chittagong, 1888 to 1898 (Calcutta, 1900). Correspondence on the settlement of the Noabad lands in the district of Chittagong (Calcutta, 1889). 71 BL Mss. Add. 29086-29088 Ameen Accounts: a return made in the year 1778 by, a commission for collecting materials or settling the revenue of Bengal, compiled from Native Records, and brought down to A.H. 1183 (1769) 3vols., Mss Add. 29088 fol. 57. Bengal District Records. Chittagong vol. 1 1760-1773 (Letters received and issued) ed. W.K. Firminger (Calcutta, 1923). 72 A.M. Serajuddin, The revenue administration of the East India Company in Chittagong 1761-1785 (Chittagong, 1971), pp. 189-205. 73 Talish, Fatiyyah-i-ibriyyah , fol. 152a-152b. See also J. N. Sarkar, The Feringi pirates of Chatgaon, 1665 AD, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 3.6 (1907), p. 425.

74

NA VOC 1252 fol. 401-416 Letter of Daniel Six to Batavia, dated Arakan 30 January 1665, fol. 408. Cf Leider, Taxation, p. 77. 75 Dagh-register vol. 1636, entry for 14 March 1636, pp. 35-25; vol. 1637 entries for 13 February 1637, pp. 41-45, 8 March 1637, pp. 71-73; vol. 1640-1641, entries for 24 January 1641, pp. 167-170, 16 March 1641, p. 211; vol. 1641-1642 entries for 24 April 1642, pp. 140-141, 1 May 1642, p. 145; vol. 1643-1644, entry for 19 March 1644, p. 41.

You might also like

- Buddhist King With Muslim NamesDocument21 pagesBuddhist King With Muslim NamesKhin Maung MyintNo ratings yet

- Afzal Ahmed Syed and Contemporary Urdu Poetry of PakistanDocument25 pagesAfzal Ahmed Syed and Contemporary Urdu Poetry of PakistanBaisakhi MitraNo ratings yet

- The Constantinople EraDocument10 pagesThe Constantinople EraMilica CvetkovicNo ratings yet

- Excavations at Kankia - 12-13 Final For ORDocument15 pagesExcavations at Kankia - 12-13 Final For ORKristyn FitzgeraldNo ratings yet

- Gifts of Time: Watches and Clocks in Ottoman-British Diplomacy, 1693-1803Document25 pagesGifts of Time: Watches and Clocks in Ottoman-British Diplomacy, 1693-1803Dinçer SunaNo ratings yet

- Architecture Art StylesDocument8 pagesArchitecture Art Stylespratyusha biswas 336No ratings yet

- PersianCivilization PDFDocument9 pagesPersianCivilization PDFZo-an Persia SequitinNo ratings yet

- Arab ConquestDocument5 pagesArab ConquestRaja SirajNo ratings yet

- Hinduism in Southeast AsiaDocument7 pagesHinduism in Southeast AsiaPriya SeshadriNo ratings yet

- West Bengal Tourism PolicyDocument6 pagesWest Bengal Tourism Policyapi-3711789100% (3)

- Romantic Influence in Modern Art Draft 2Document15 pagesRomantic Influence in Modern Art Draft 2api-221261465100% (1)

- BlackAesthetics ReformattedDocument6 pagesBlackAesthetics ReformattedBETIE SONNITA TIQUAFONNo ratings yet

- Part 1 ISLAMIC TECHNOLOGY Transfer TO THE WEST PDFDocument14 pagesPart 1 ISLAMIC TECHNOLOGY Transfer TO THE WEST PDFMas Arman TewoNo ratings yet

- Islamic Wall Art and Its ImportanceDocument3 pagesIslamic Wall Art and Its ImportanceEngr Safeer AhmedNo ratings yet

- Nomadic Empires Class 11 Notes HistoryDocument6 pagesNomadic Empires Class 11 Notes HistoryFIROZNo ratings yet

- ImmigrationDocument6 pagesImmigrationAna GheorghiceanuNo ratings yet

- Ottoman EmpireDocument26 pagesOttoman EmpireImtanan ArifNo ratings yet

- A Manifestation of Self-Reconstruction and Reformation - Ali ShariatiDocument6 pagesA Manifestation of Self-Reconstruction and Reformation - Ali ShariatiBMT-linkNo ratings yet

- Biology NotesDocument32 pagesBiology NotesTaylor BonnetNo ratings yet

- Zaid Hamid BiographyDocument4 pagesZaid Hamid BiographyAbu AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Electron PhysicsDocument8 pagesElectron PhysicsMaryam KiyaniNo ratings yet

- Karnataka Destinations PDFDocument21 pagesKarnataka Destinations PDFsanthu_bhoomi9673No ratings yet

- History of Islamnagar FinalDocument15 pagesHistory of Islamnagar FinalSonika Patel100% (1)

- Arrival of European TradersDocument6 pagesArrival of European TradersTimothy EnglandNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Culture and ReligionDocument6 pagesDifference Between Culture and ReligionZaidbin ZafarNo ratings yet

- India Under Akbar RuleDocument11 pagesIndia Under Akbar RuleIshaq AhmedNo ratings yet

- Annotatedbibliography CrystinacastiglioneDocument6 pagesAnnotatedbibliography Crystinacastiglioneapi-199102923No ratings yet

- Thayer Insurgency in Southern ThailandDocument24 pagesThayer Insurgency in Southern ThailandCarlyle Alan Thayer100% (3)

- Exibition PoDocument8 pagesExibition PoArbainah SastrabayuNo ratings yet

- Caubet The International StyleDocument12 pagesCaubet The International StyleFred VinkNo ratings yet

- Human Geo Chapter 7 Ethnicity OutlineDocument25 pagesHuman Geo Chapter 7 Ethnicity OutlineRhonda Cantrell ApplebaumNo ratings yet

- History Catalogue 07-10Document32 pagesHistory Catalogue 07-10samantha_abela2156100% (2)

- Advent of EuropeansDocument5 pagesAdvent of EuropeansVivek Ranjan MaitreyNo ratings yet

- Archaeology of The Asura Sites in OdishaDocument7 pagesArchaeology of The Asura Sites in OdishaBibhuti Bhusan SatapathyNo ratings yet

- Kovecses Studying American Culture Through Its Metaphors Dimensions of Variation and Frames of ExperienceDocument19 pagesKovecses Studying American Culture Through Its Metaphors Dimensions of Variation and Frames of ExperienceAngela ZenonNo ratings yet

- PersianLitInIndia PDFDocument13 pagesPersianLitInIndia PDFMohammed ArshadNo ratings yet

- Early River Valley CivilizationsDocument19 pagesEarly River Valley CivilizationsGokul SusindranNo ratings yet

- The Hermeneutical Community and The Task of Contextual Engagement (Maggay)Document16 pagesThe Hermeneutical Community and The Task of Contextual Engagement (Maggay)Michael R. CariñoNo ratings yet

- A History of The East German and GothicDocument9 pagesA History of The East German and GothicGodhaelanNo ratings yet

- Steven Dutch - The Rise of Mongol PowerDocument10 pagesSteven Dutch - The Rise of Mongol PowerwinterblossomNo ratings yet

- Two Nation Theory Myth or RealityDocument10 pagesTwo Nation Theory Myth or RealityKashif AfridiNo ratings yet

- Maritime Relation of Kalinga With Srilanka: Dr. Kandarpa PatelDocument7 pagesMaritime Relation of Kalinga With Srilanka: Dr. Kandarpa PatelBhikkhu Kesara0% (1)

- Rootsand Branchesof Psychology SP 05Document13 pagesRootsand Branchesof Psychology SP 05Bakhtawar GillNo ratings yet

- Theory of Electrostatics: Electric ChargeDocument8 pagesTheory of Electrostatics: Electric ChargeAbrahamRubioNo ratings yet

- The History and Territorial Evolution of The ChristianityDocument8 pagesThe History and Territorial Evolution of The ChristianityAndrej2008No ratings yet

- Electric Fields & CapacitorsDocument19 pagesElectric Fields & CapacitorsMohsen SaidiNo ratings yet

- 05 - Experience As A Source For TheologyDocument28 pages05 - Experience As A Source For TheologyEliceo Saavedra RiosNo ratings yet

- Dawah How To Speak To People of Other FaithsDocument13 pagesDawah How To Speak To People of Other FaithsahmadsiraziNo ratings yet

- Indus Valley CivilisationDocument4 pagesIndus Valley CivilisationRohan PandhareNo ratings yet

- Realism (1840s - 1880s)Document9 pagesRealism (1840s - 1880s)Keane ChuaNo ratings yet

- Islamic Education Movement: Recent History and Objectives Shah Abdul HannanDocument6 pagesIslamic Education Movement: Recent History and Objectives Shah Abdul Hannanروحايذول بن يونسNo ratings yet

- The Muslims and Sri LankaDocument11 pagesThe Muslims and Sri LankalakmuslimNo ratings yet

- Hasan Le Gai EatonDocument10 pagesHasan Le Gai EatonmajnunwayfarerNo ratings yet

- Tourism: A Driving Force For Poverty Alleviation, Job Creation & Social HarmonyDocument4 pagesTourism: A Driving Force For Poverty Alleviation, Job Creation & Social Harmonytayyab_mir_4No ratings yet

- Krishna Deva RayaDocument4 pagesKrishna Deva Rayadrmsrmurty9473No ratings yet

- First Europeans in IndiaDocument9 pagesFirst Europeans in IndiaAnonymous v5QjDW2eHxNo ratings yet

- SolarDocument39 pagesSolarLannie MaiquezNo ratings yet

- China and The Chinese According To 5-13th Century Classical Armenian SourcesDocument8 pagesChina and The Chinese According To 5-13th Century Classical Armenian SourcesRobert G. BedrosianNo ratings yet

- GuySanders PDFDocument5 pagesGuySanders PDFЈелена Ј.No ratings yet

- 1887 - 12637-Chapter 2Document30 pages1887 - 12637-Chapter 2yatha winthaNo ratings yet

- Muslim in ArakanDocument31 pagesMuslim in ArakanAung Kyaw SeinNo ratings yet

- Muslim in ArakanDocument31 pagesMuslim in ArakanAung Kyaw SeinNo ratings yet

- Master Thesis Final Version 12th Jan 2011 Araki Sensei 1Document118 pagesMaster Thesis Final Version 12th Jan 2011 Araki Sensei 1Aung Kyaw SeinNo ratings yet

- A New Palace For Mra Swan Dewi: Changes in Spirit Cults in Arakan (Rakhine) StateDocument26 pagesA New Palace For Mra Swan Dewi: Changes in Spirit Cults in Arakan (Rakhine) StateAung Kyaw SeinNo ratings yet

- On The Evoulution of Rohingya ProblemDocument69 pagesOn The Evoulution of Rohingya ProblemPhone HlaingNo ratings yet

- Stanley Commercial Hardware 2014 Price BookDocument124 pagesStanley Commercial Hardware 2014 Price BookSecurity Lock DistributorsNo ratings yet

- Gmu Unofficial TranscriptDocument3 pagesGmu Unofficial Transcriptapi-491861804No ratings yet

- 10 BDDDocument39 pages10 BDDEliana NaviaNo ratings yet

- Top Notch 1, 3° Edicion Workbook Answer KeyDocument14 pagesTop Notch 1, 3° Edicion Workbook Answer KeyLuis Lopez90% (61)

- Digit Sep 09Document107 pagesDigit Sep 09dukerexNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Bicarbonate Additive On Corrosion ResistanceDocument11 pagesThe Effect of Bicarbonate Additive On Corrosion ResistancebexigaobrotherNo ratings yet

- Iwcf Section OneDocument20 pagesIwcf Section OnesuifengniliuNo ratings yet

- Strategic PlanningDocument24 pagesStrategic PlanningSara Sharma0% (1)

- GR No. 188213 - January 11, 2016 FACTS: Herein Petitioner, Natividad Cruz, Was The Punong Barangay or Chairperson of BarangayDocument6 pagesGR No. 188213 - January 11, 2016 FACTS: Herein Petitioner, Natividad Cruz, Was The Punong Barangay or Chairperson of BarangayAilyn GaluraNo ratings yet

- Towards Improvement of The Rights and Duties of Mutawalli and Nazir in The Management And..Document17 pagesTowards Improvement of The Rights and Duties of Mutawalli and Nazir in The Management And..Mutqinah SshiNo ratings yet

- General Milling Corp Vs CA (DIGEST)Document2 pagesGeneral Milling Corp Vs CA (DIGEST)Raima Marjian Sucor100% (1)

- " My Heart Will Go On ": Vocal: Celine DionDocument8 pages" My Heart Will Go On ": Vocal: Celine DionLail Nugraha PratamaNo ratings yet

- Extractive Metallurgy Pachuca Tank DesignDocument8 pagesExtractive Metallurgy Pachuca Tank DesignXtet AungNo ratings yet

- DO 31 s2020Document18 pagesDO 31 s2020charles barkleyNo ratings yet

- Divisional Sec. Contact Details 2019-03-01-UpdateDocument14 pagesDivisional Sec. Contact Details 2019-03-01-Updatedotr9317No ratings yet

- Nacc NCCRDocument6 pagesNacc NCCRChaitra Gn100% (1)

- Hospital DocumentsDocument17 pagesHospital DocumentsRaviraj PisheNo ratings yet

- Contract of EmploymentDocument5 pagesContract of EmploymentFarisNo ratings yet

- Bugreport Fog - in SKQ1.211103.001 2023 04 10 19 23 21 Dumpstate - Log 9097Document32 pagesBugreport Fog - in SKQ1.211103.001 2023 04 10 19 23 21 Dumpstate - Log 9097chandrakanth reddyNo ratings yet

- Numerical Techniques For Global AtmosphericDocument577 pagesNumerical Techniques For Global AtmosphericTatiana N. LeónNo ratings yet

- EE/CS-320 - Computer Organization & Assembly Language (Fall Semester 2013-14) Assignment 2Document11 pagesEE/CS-320 - Computer Organization & Assembly Language (Fall Semester 2013-14) Assignment 2Haris AliNo ratings yet

- Review Accounting NotesDocument9 pagesReview Accounting NotesJasin LujayaNo ratings yet

- Shalina Healthcare JD - Business AnalyticsDocument2 pagesShalina Healthcare JD - Business AnalyticsMeow bunNo ratings yet

- Measuring Food Safety Culture in Food Manufacturing-59-173!50!115Document66 pagesMeasuring Food Safety Culture in Food Manufacturing-59-173!50!115ômąŕ ĕżžãőůįNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Sample CommerceDocument4 pagesDissertation Sample CommerceBuyPapersOnlineForCollegeCanada100% (1)

- SIFI-131 Fire Protection in Electrical Equipment RoomsDocument8 pagesSIFI-131 Fire Protection in Electrical Equipment RoomsemiljanlazeNo ratings yet

- ESAT FormulaDocument11 pagesESAT FormulaSKYE LightsNo ratings yet

- OOAD Documentation (Superstore)Document15 pagesOOAD Documentation (Superstore)Umâir KhanNo ratings yet

- 147380-1 Motoman XRC Controller Fieldbus (XFB01) Instruction ManualDocument102 pages147380-1 Motoman XRC Controller Fieldbus (XFB01) Instruction Manualrubi monNo ratings yet

- Repair of Small Household Appliances and Power ToolsDocument315 pagesRepair of Small Household Appliances and Power ToolsahmadnawazjaswalNo ratings yet

- Bind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next DoorFrom EverandBind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next DoorRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (77)

- The Lost Peace: Leadership in a Time of Horror and Hope, 1945–1953From EverandThe Lost Peace: Leadership in a Time of Horror and Hope, 1945–1953No ratings yet

- Project MK-Ultra: The History of the CIA’s Controversial Human Experimentation ProgramFrom EverandProject MK-Ultra: The History of the CIA’s Controversial Human Experimentation ProgramRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (13)

- The Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hotel Ritz in ParisFrom EverandThe Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hotel Ritz in ParisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (49)

- We Crossed a Bridge and It Trembled: Voices from SyriaFrom EverandWe Crossed a Bridge and It Trembled: Voices from SyriaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (30)

- Rebel in the Ranks: Martin Luther, the Reformation, and the Conflicts That Continue to Shape Our WorldFrom EverandRebel in the Ranks: Martin Luther, the Reformation, and the Conflicts That Continue to Shape Our WorldRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Dunkirk: The History Behind the Major Motion PictureFrom EverandDunkirk: The History Behind the Major Motion PictureRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (19)

- Digital Gold: Bitcoin and the Inside Story of the Misfits and Millionaires Trying to Reinvent MoneyFrom EverandDigital Gold: Bitcoin and the Inside Story of the Misfits and Millionaires Trying to Reinvent MoneyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (51)

- Hubris: The Tragedy of War in the Twentieth CenturyFrom EverandHubris: The Tragedy of War in the Twentieth CenturyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (23)

- The Rape of Nanking: The History and Legacy of the Notorious Massacre during the Second Sino-Japanese WarFrom EverandThe Rape of Nanking: The History and Legacy of the Notorious Massacre during the Second Sino-Japanese WarRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (63)

- Hunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziFrom EverandHunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (157)

- The Great Fire: One American's Mission to Rescue Victims of the 20th Century's First GenocideFrom EverandThe Great Fire: One American's Mission to Rescue Victims of the 20th Century's First GenocideNo ratings yet

- Making Gay History: The Half-Century Fight for Lesbian and Gay Equal RightsFrom EverandMaking Gay History: The Half-Century Fight for Lesbian and Gay Equal RightsNo ratings yet

- 1963: The Year of the Revolution: How Youth Changed the World with Music, Fashion, and ArtFrom Everand1963: The Year of the Revolution: How Youth Changed the World with Music, Fashion, and ArtRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Witness to Hope: The Biography of Pope John Paul IIFrom EverandWitness to Hope: The Biography of Pope John Paul IIRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (58)

- The Quiet Man: The Indispensable Presidency of George H.W. BushFrom EverandThe Quiet Man: The Indispensable Presidency of George H.W. BushRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Desperate Sons: Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, John Hancock, and the Secret Bands of Radicals Who Led the Colonies to WarFrom EverandDesperate Sons: Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, John Hancock, and the Secret Bands of Radicals Who Led the Colonies to WarRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- Reagan at Reykjavik: Forty-Eight Hours That Ended the Cold WarFrom EverandReagan at Reykjavik: Forty-Eight Hours That Ended the Cold WarRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Never Surrender: Winston Churchill and Britain's Decision to Fight Nazi Germany in the Fateful Summer of 1940From EverandNever Surrender: Winston Churchill and Britain's Decision to Fight Nazi Germany in the Fateful Summer of 1940Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (45)

- The Future of Capitalism: Facing the New AnxietiesFrom EverandThe Future of Capitalism: Facing the New AnxietiesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Knowing What We Know: The Transmission of Knowledge: From Ancient Wisdom to Modern MagicFrom EverandKnowing What We Know: The Transmission of Knowledge: From Ancient Wisdom to Modern MagicRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (25)

- The OSS and CIA: The History of America’s Intelligence Community during World War II and the Establishment of the Central Intelligence AgencyFrom EverandThe OSS and CIA: The History of America’s Intelligence Community during World War II and the Establishment of the Central Intelligence AgencyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (27)

- The Pursuit of Happiness: How Classical Writers on Virtue Inspired the Lives of the Founders and Defined AmericaFrom EverandThe Pursuit of Happiness: How Classical Writers on Virtue Inspired the Lives of the Founders and Defined AmericaRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- They All Love Jack: Busting the RipperFrom EverandThey All Love Jack: Busting the RipperRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (30)

- Midnight in Chernobyl: The Story of the World's Greatest Nuclear DisasterFrom EverandMidnight in Chernobyl: The Story of the World's Greatest Nuclear DisasterRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (410)

- Principles for Dealing with the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed or FailFrom EverandPrinciples for Dealing with the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed or FailRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (237)

- Voyagers of the Titanic: Passengers, Sailors, Shipbuilders, Aristocrats, and the Worlds They Came FromFrom EverandVoyagers of the Titanic: Passengers, Sailors, Shipbuilders, Aristocrats, and the Worlds They Came FromRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (86)

- The Faithful Executioner: Life and Death, Honor and Shame in the Turbulent Sixteenth CenturyFrom EverandThe Faithful Executioner: Life and Death, Honor and Shame in the Turbulent Sixteenth CenturyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (77)