Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Modern Drama

Uploaded by

artedentaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Modern Drama

Uploaded by

artedentaCopyright:

Available Formats

The Modern Drama

Modernism was a predominantly European movement that developed as a selfconscious break from traditional artistic forms. It represents a significant shift in cultural sensibilities, often attributed to the fallout of World War I. At first, modernist theatre was in large part an attempt to realize the reformed stage on naturalistic principles as advocated by Emile Zola in the 1880s. However, a simultaneous reaction against naturalism urged the theatre in a much different direction. Owing much to symbolism, the movement attempted to integrate poetry, painting, music, and dance in a harmonious fusion. Both of these seemingly conflicting movements fit under the term 'Modernism'. MODERN THEATER: 18th - 20th centuries The History of Theatre in the 18th, 19th and 20th Centuries is one of the increasing commercialization of the art, accompanied by technological innovations, the introduction of serious critical review, expansion of the subject matters portrayed to include ordinary people, and an emphasis on more natural forms of acting. Theatre, which had been dominated by the Church for centuries, and then by the tastes of monarchs for more than 200 years, became accessible to merchants, industrialists, the bourgeois and then the masses. The Eighteenth Century Theatre in England during the 18th Century was dominated by an actor of genius, David Garrick (1717-1779), who was also a manager and playwright. Garrick emphasized a more natural form of speaking and acting that mimicked life. His performances had a tremendous impact on the art of acting, from which ultimately grew movements such as realism and naturalism. Garrick finally banished the audience from the stage, which shrunk to behind the proscenium where the actors now performed among the furnishings, scenery and stage settings. Plays now dealt with ordinary people as characters, such as in She Stoops to Conquer by Oliver Goldsmith (1730-1734), and The School for Scandal by Richard Sheridan. This was the result of the influence of such philosophers as Voltaire and the growing desire for freedom among a populace, both in Europe and North America, which was, with advances in technology, beginning to find the time and means for leisurely occupations such as patronizing commercial theatre. It was also in the 18th Century that commercial theatre began to make its appearance in the colonies of North America. The Nineteenth Century During the 19th Century, the Industrial Revolution changed the way people lived and worked -- and it changed the face of theatre as well. Gas lighting was first introduced in 1817, in London's Drury Lane Theatre. Arc-lighting followed and, by the end of the century, electrical lighting made its appearance on stage. The necessity of controlling lighting effects made it imperative, once and for all, that the actors retreat behind the proscenium (until the reappearance of open stages and theatre in the round in the 20th Century). The poor quality of lighting probably contributed to the growth of melodrama in the mid-19th Century, where the emphasis was less on content and acting, and more on action and spectacle. Elaborate mechanisms for the changing and flying of scenery were developed, including fly-lofts, elevators, and revolving stages. Playwrights, due to the tastes of the public and copyright laws of the times, were poorly paid, and the result was the ascendancy of the actor and the action over the author until later in the century with the appearance of great playwrights such as Henrik Ibsen (1828-

1906), George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950), and Anton Chekov (1860-1904). That serious drama continued to develops during this time is witnessed not only by these and similar authors, but by the work of the actor and director, Konstantin Stanislavsky (1865-1938), who wrote several works on the art of acting, including An Actor Prepares, which laid the foundations for the "method" of the Actor's Studio in the 20th Century. The Twentieth Century The 20th Century has witnessed the two greatest wars in history and social upheaval without parallel. The political movements of the "proletariat" were manifested in theatre by such movements as realism, naturalism, symbolism, impressionism and, ultimately, highly stylized anti-realism -- particularly in the early 20th Century -- as society battled to determine the ultimate goals and meaning of political philosophy in the life of the average person. At the same time, commercial theatre advanced full force, manifesting itself in the development of vastly popular forms of drama such as major musicals beginning with Ziegfelds Follies and developing into full-blown musical plays such as Oklahoma!, Porgy and Bess, and Showboat. Ever greater technological advances permitted spectacular shows such as The Phantom of the Opera and Miss Saigon to offer competition to another new innovation: film. Ultimately, the cost of producing major shows such as these, combined with the organization of actors and technical persons in theatre, have limited what live theatre can do in competing with Hollywood. Serious drama also advanced in the works of Eugene O'Neill (1888-1953) in his trilogy Mourning Becomes Electra and in The Iceman Cometh; Arthur Miller (1915- ), in The Crucible and Death of a Salesman; and Tennessee Williams (1911-1983), whose Glass Menagerie, produced immediately after World War II, arguably changed the manner in which tragic drama is presented. Serious drama was accompanied by serious acting in the form of the Actor's Studio, founded in 1947 by Elia Kazan and others, later including Lee Strasberg. The art of writing comedy was brought to a level of near-perfection (and commercial success) by Neil Simon (1927- ), whose plays such as Rumours, The Odd Couple, and The Prisoner of Second Avenue, are among the favourites for production by community theatres. From the time of the Renaissance on, theatre seemed to be striving for total realism, or at least for the illusion of reality. As it reached that goal in the late 19th century, a multifaceted, anti-realistic reaction erupted. Avant-garde Precursors of Modern Theatre Many movements generally lumped together as the avant-garde, attempted to suggest alternatives to the realistic drama and production. The various theoreticians felt that Naturalism presented only superficial and thus limited or surface reality-that a greater truth or reality could be found in the spiritual or the unconscious. Others felt that theatre had lost touch with its origins and had no meaning for modern society other than as a form of entertainment. Paralleling modern art movements, they turned to symbol, abstraction, and ritual in an attempt to revitalize the theatre. Although realism continues to be dominant in contemporary theatre, television and film now better serve its earlier functions. The originator of many antirealist ideas was the German opera composer Richard Wagner. He believed that the job of the playwright/composer was to create myths. In so doing, Wagner felt, the creator of drama was portraying an ideal world in which the audience shared a communal experience, perhaps as the ancients had done. He sought to depict the "soul state", or inner being, of characters rather than their superficial, realistic aspects. Furthermore, Wagner was unhappy with the lack of unity among the individual arts that constituted the drama. He proposed the Gesamtkunstwerk, the "total art work", in which all dramatic elements are unified, preferably under the control of a single artistic creator.

Wagner was also responsible for reforming theatre architecture and dramatic presentation with his Festival Theatre at Bayreuth, Germany, completed in 1876. The stage of this theatre was similar to other 19th-century stages even if better equipped, but in the auditorium Wagner removed the boxes and balconies and put in a fan-shaped seating area on a sloped floor, giving an equal view of the stage to all spectators. Just before a performance the auditorium lights dimmed to total darkness-then a radical innovation. The modern drama does not purport to be easy; it insists on a greater understanding of all things pertinent to modern humanity and its relationships to religion, societal order, and psychology in order to appreciate its message; however, it critically acknowledges that most of us remain ignorant to all the former. Thus, the drama instructs, irritates, challenges, and begs for intelligence in order to gain from its message. It remains didactic, combined with pleasure, but always wishing to challenge the current notions of authority.

MODERN DRAMA

Name: Anggun Erik V. Dewi Aminah Nur Isni Widiarti Wahyu Ganda R. Wulan Nur Endah Siswo Saputra English Department A

TEACHERS TRAINING AND EDUCATION FACULTY PEKALONGAN UNVERSITY 2013

You might also like

- Futurist Theatre Performance TacticsDocument8 pagesFuturist Theatre Performance TacticsBrittanie TrevarrowNo ratings yet

- German Theatre: Reporter: Jared Jane G. MaglenteDocument55 pagesGerman Theatre: Reporter: Jared Jane G. MaglenteMercy TrajicoNo ratings yet

- 20th Century American DramaDocument12 pages20th Century American Dramanikolic_dan5380No ratings yet

- Chapter 11 Modernism and TheatreDocument10 pagesChapter 11 Modernism and TheatreGauravKumar100% (1)

- Modern Drama StuffDocument16 pagesModern Drama Stuffsimsalabima1No ratings yet

- RealismDocument9 pagesRealismAyesha Susan ThomasNo ratings yet

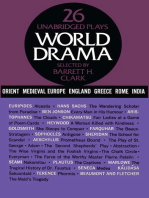

- World Drama, Volume 1: 26 Unabridged PlaysFrom EverandWorld Drama, Volume 1: 26 Unabridged PlaysRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Theatre History PowerpointDocument77 pagesTheatre History PowerpointSarah Lecheb100% (2)

- Renaissance Theatre ArchitectureDocument19 pagesRenaissance Theatre Architecturemalvina902009No ratings yet

- Roman TheatreDocument4 pagesRoman TheatreViki XatzichrysafiNo ratings yet

- Theatre Spaces ExplainedDocument7 pagesTheatre Spaces ExplainedTasya Haslam0% (1)

- Japanese Theatre Transcultural: German and Italian IntertwiningsDocument1 pageJapanese Theatre Transcultural: German and Italian IntertwiningsDiego PellecchiaNo ratings yet

- Complicite Theatre - Simon McburneyDocument1 pageComplicite Theatre - Simon Mcburneyapi-364338283No ratings yet

- Greek and Roman Theatre HistoryDocument59 pagesGreek and Roman Theatre HistoryAdrian BagayanNo ratings yet

- The History of MimesDocument5 pagesThe History of Mimesapi-205951292No ratings yet

- ExpressionismDocument13 pagesExpressionismAndrei Raicu100% (1)

- A Presentation By: Elena Pundjeva Nikolay RaykovDocument13 pagesA Presentation By: Elena Pundjeva Nikolay RaykovDirklenartNo ratings yet

- Theatrical Design Handbook 2017-182Document23 pagesTheatrical Design Handbook 2017-182api-330010982No ratings yet

- Performance and Value: The Work of Theatre in Karl Marx's Critique of Political EconomyDocument21 pagesPerformance and Value: The Work of Theatre in Karl Marx's Critique of Political EconomyLizzieGodfrey-GushNo ratings yet

- PERFORMING ARTS JOHN DERICK TUBODocument13 pagesPERFORMING ARTS JOHN DERICK TUBOJubilee DatinginooNo ratings yet

- Kozintsev On Lear and HamletDocument7 pagesKozintsev On Lear and HamletChandrima BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Meyerhold'sDocument15 pagesMeyerhold'sSquawNo ratings yet

- Theatre DevelopmentDocument6 pagesTheatre DevelopmentBlessing Joseph BenNo ratings yet

- A Walk of Art: The Potential of The Sound Walk As Practice in Cultural GeographyDocument21 pagesA Walk of Art: The Potential of The Sound Walk As Practice in Cultural GeographyGilles MalatrayNo ratings yet

- Theatre of Ancient Greece 1Document7 pagesTheatre of Ancient Greece 1rakeshrkumarNo ratings yet

- History of Theatre - GreekDocument14 pagesHistory of Theatre - GreekJC SouthNo ratings yet

- Presentation by The Bog of CatsDocument22 pagesPresentation by The Bog of CatsEftichia SpyridakiNo ratings yet

- Japanese Dramaturgy 1Document15 pagesJapanese Dramaturgy 1Myrna MañiboNo ratings yet

- History of Medieval DramaDocument9 pagesHistory of Medieval DramaManoj KanthNo ratings yet

- NYUPET Intro to Theatre of the Oppressed Devising GuidelinesDocument2 pagesNYUPET Intro to Theatre of the Oppressed Devising GuidelinesrealkoNo ratings yet

- Bywater-Milton and The Aristotelian Definition of TragedyDocument9 pagesBywater-Milton and The Aristotelian Definition of TragedyjiporterNo ratings yet

- Elizabethan TheatreDocument15 pagesElizabethan TheatretanusreeghoshNo ratings yet

- Theatre of the Absurd ExplainedDocument7 pagesTheatre of the Absurd ExplainedAnamaria OnițaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 Experimental Theatre-IDocument6 pagesChapter 8 Experimental Theatre-IGauravKumarNo ratings yet

- Greek TheatreDocument20 pagesGreek TheatreBrooklynNo ratings yet

- Wendell Cole - The Theatre Projects of Walter GropiousDocument8 pagesWendell Cole - The Theatre Projects of Walter GropiousNeli Koutsandrea100% (1)

- Helene Modern Performance and Adaptation of Greek Tragedy - 1999Document13 pagesHelene Modern Performance and Adaptation of Greek Tragedy - 1999Barbara AntoniazziNo ratings yet

- (Cambridge Studies in Modern Theatre) Richard Boon, Jane Plastow, Wole Soyinka-Theatre Matters - Performance and Culture On The World Stage-Cambridge University Press (1999) PDFDocument225 pages(Cambridge Studies in Modern Theatre) Richard Boon, Jane Plastow, Wole Soyinka-Theatre Matters - Performance and Culture On The World Stage-Cambridge University Press (1999) PDFsuleman husseiniNo ratings yet

- 1.western Theatre HistoryDocument6 pages1.western Theatre Historyapi-3711271No ratings yet

- Woman In Black Play Critique at Ocala Civic TheatreDocument5 pagesWoman In Black Play Critique at Ocala Civic TheatreBrix Quiza CervantesNo ratings yet

- 18th Century Theatre Forms and Staging TrendsDocument39 pages18th Century Theatre Forms and Staging TrendsSham ShamNo ratings yet

- Antigone - Video WorkpackDocument3 pagesAntigone - Video WorkpackClayesmoreDramaNo ratings yet

- Greek and Roman TheaterDocument25 pagesGreek and Roman Theateranne.lyt100% (1)

- Architecture and Drama The Theatre of Public SpaceDocument10 pagesArchitecture and Drama The Theatre of Public Spacendr_movila7934No ratings yet

- Ancient Greek TheatreDocument16 pagesAncient Greek TheatreStyli Von GreeceNo ratings yet

- All About Pygmalion and It's AuthorDocument1 pageAll About Pygmalion and It's Authoroctavianc96100% (1)

- Street Theatre-Development CommunicationDocument10 pagesStreet Theatre-Development CommunicationThomas ChennattuNo ratings yet

- Nigerian Theatre and Drama Evolution and Relevance in A Modern Nigeria byDocument7 pagesNigerian Theatre and Drama Evolution and Relevance in A Modern Nigeria byYohanna Yakubu IsraelNo ratings yet

- Play Script Analysis SCHEDULE SP 2017Document3 pagesPlay Script Analysis SCHEDULE SP 2017Erika BaileyNo ratings yet

- 40 / Sarai Reader 2002: The Cities of Everyday Life: Parsi Theatre and The City Locations, Patrons, AudiencesDocument8 pages40 / Sarai Reader 2002: The Cities of Everyday Life: Parsi Theatre and The City Locations, Patrons, AudiencesManali TalakeNo ratings yet

- Commedia Dell'ArteDocument19 pagesCommedia Dell'ArteSjf WilsonNo ratings yet

- Director's Notes For Hamlet's First SoliloquyDocument5 pagesDirector's Notes For Hamlet's First SoliloquyDee Yana0% (1)

- Performing Arts 1 HistoryDocument21 pagesPerforming Arts 1 HistoryFacundo Antonietti50% (2)

- Meat Is TheatreDocument12 pagesMeat Is TheatreAmy Cecilia LeighNo ratings yet

- Britten and SymbolismDocument20 pagesBritten and SymbolismJason LiebsonNo ratings yet

- Theory and Practice in Erdmann, Becce, Brav's 'Allgemeines Handbuch Der Film-Musik' (1927)Document9 pagesTheory and Practice in Erdmann, Becce, Brav's 'Allgemeines Handbuch Der Film-Musik' (1927)Scott RiteNo ratings yet

- Katie MitchellDocument3 pagesKatie Mitchellapi-568417403No ratings yet

- Greek Theatre: A Presentation by Shamiso Chiza Drama, Form 3Document20 pagesGreek Theatre: A Presentation by Shamiso Chiza Drama, Form 3Shamiso ChizaNo ratings yet

- Cherry Orchard Study Guide Nor A TheatreDocument27 pagesCherry Orchard Study Guide Nor A TheatretoobaziNo ratings yet

- Aveyond 1 - Rhen's Quest WalkTrough PDFDocument48 pagesAveyond 1 - Rhen's Quest WalkTrough PDFartedenta86% (7)

- Bang OneDocument2 pagesBang OneartedentaNo ratings yet

- Eggs: Magic Mirror Express: Goodie Caves: Chests:: HarburgDocument1 pageEggs: Magic Mirror Express: Goodie Caves: Chests:: HarburgartedentaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Simple Present Tense through ConversationDocument7 pagesTeaching Simple Present Tense through ConversationartedentaNo ratings yet

- Walkthrough For Aveyond - LOTDocument31 pagesWalkthrough For Aveyond - LOTChad López Maamo100% (3)

- Walkthrough - Aveyond 2 Ean's QuestDocument25 pagesWalkthrough - Aveyond 2 Ean's Questmtvdw100% (3)

- Brightwood Forest Catacombs Chest LocationsDocument1 pageBrightwood Forest Catacombs Chest LocationsartedentaNo ratings yet

- Makalah ReviewDocument2 pagesMakalah ReviewartedentaNo ratings yet

- Review BookDocument4 pagesReview BookartedentaNo ratings yet

- Modern Theater's EvolutionDocument3 pagesModern Theater's Evolutionartedenta100% (1)

- April 14Document2 pagesApril 14artedentaNo ratings yet

- Rencana Pelaksanaan Pembelajaran IndoDocument5 pagesRencana Pelaksanaan Pembelajaran IndoartedentaNo ratings yet

- How To Review A BookDocument6 pagesHow To Review A BookartedentaNo ratings yet

- King ArthurDocument1 pageKing ArthurartedentaNo ratings yet

- How To Review A BookDocument3 pagesHow To Review A Bookartedenta100% (2)

- AsdasdasdDocument6 pagesAsdasdasdartedentaNo ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension TestDocument17 pagesReading Comprehension Testartedenta100% (1)

- Writing Clearly and ConcicelyDocument30 pagesWriting Clearly and ConcicelyartedentaNo ratings yet

- RemegDocument4 pagesRemegartedentaNo ratings yet

- A AAAAAaDocument45 pagesA AAAAAaartedentaNo ratings yet

- Death Note SketchDocument1 pageDeath Note SketchartedentaNo ratings yet

- AikeDocument5 pagesAikeartedentaNo ratings yet

- BelajarDocument6 pagesBelajarartedentaNo ratings yet

- We Now Have Four Phrases To ParseDocument4 pagesWe Now Have Four Phrases To ParseartedentaNo ratings yet

- English Eaching MethodDocument1 pageEnglish Eaching MethodartedentaNo ratings yet

- We Now Have Four Phrases To ParseDocument4 pagesWe Now Have Four Phrases To ParseartedentaNo ratings yet

- The Prepositional PhraseDocument12 pagesThe Prepositional PhraseartedentaNo ratings yet

- We Now Have Four Phrases To ParseDocument4 pagesWe Now Have Four Phrases To ParseartedentaNo ratings yet