Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Instruments of Empire - Peter Gowan

Uploaded by

peterVoterCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Instruments of Empire - Peter Gowan

Uploaded by

peterVoterCopyright:

Available Formats

reviews

Andrew Bacevich, American Empire: The Realities and Consequences of US Diplomacy Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA 2002, $29.95, hardback 320 pp, 0 674 00940 1

Peter Gowan

INSTRUMENTS OF EMPIRE

With the collapse of the Soviet Bloc, conventional accounts of the worldwide expansion of American power since the outbreak of the Pacific War have been in some disarray. The standard version of us power-projection abroad has held that it was called forth by the overriding need, first to liberate Europe and Japan from Fascism, and then to protect democracies everywhere from the ussr and Communism. Logically, then, once the Free World was no longer threatened either by Fascism or Communism, the global operations of the American state ought to have been scaled back. But in fact they have extended yet further, into regions of the earth of which few in Washington had ever dreamed. As the ideological fog of the Cold War cleared, what was revealed was a special kind of imperial state with huge military and civil bureaucracies, flanked by massive business organizations, jutting out into large zones of Eurasia, South America and other parts of the world. How was this to be explained? Through much of the 90s, the new landscape was still in part obscured by the vapours of globalization, propagated by sociologists and speechwriters of the Western establishment. Since the turn of the century, however, it has become more difficult to ignore, and there is now a growing volume of literature seeking to address it. In this field, American Empire strikes a singularly refreshing note. The historian who has written it, Andrew Bacevich, is a former military officer, whose voice retains something of his army background: his picture on the dust-jacket suggests a more amiable and good-looking version of Oliver North. But there is nothing barracks-like about his prose. American Empire is a tonic to read: crisp, vivid, pungent, with a dry sense of humour and sharp sense of hypocrisies. Bacevich is

new left review 21

may june 2003

147

148

nlr 21

a conservative, who explains that he believed in the justice of Americas war against Communism, and continues to do so, but once it was over came to the conclusion that us expansionism both preceded and exceeded the logic of the Cold War, and needed to be understood in a longer, more continuous historical dure. The search for an intellectual perspective that could grasp the dynamics of imperial power led this Army colonel to cross political tracks and find answers in two bodies of work associated, in different contexts, with the American Leftthe writings of Charles Beard, in the inter-war years, and William Appleman Williams, from the 1950s to the 1970s. Both these historians had insisted that the United States, contrary to official liberal mythology, was an expansionist powernot drawn to generous actions abroad by lofty internationalist ideals, but driven towards ceaseless diplomatic and military interventions across the world by forces deeply rooted within American society at home. In the 1920s Beard, already famous for his economic interpretations of the Constitution and the Civil War, turned his attention to us foreign policy, and concludedconsistently with the general focus of his workthat as the domestic market was saturated and capital heaped up for investment, the pressure for the expansion of the American commercial empire rose with corresponding speed. Fearing the consequences of this dynamic, Beard advocated an alternative route of development, much in the spirit of Hobson in England: the better way forward was to deepen the domestic market by raising the living standards of American workers and investing in social programmes at home. The great obstacle to such a path lay in the fear of the American business class that such deepening might unleash political forces that would undermine the entrenched privileges of the propertied classes within the United States itself. For this bloc, if domestic prosperity was to be maintained without sacrifice of economic hierarchy, capital accumulation would have to be re-wired to external expansion. War and conquest had to be accepted as the price of social peace at home. Nations, said Beard, are governed by their interests as their statesmen conceive those interests. In the United States, the principal business of the state was business. Banks and corporations were the real motors of the foreign policy that had pushed America into the First World War, and were driving it towards a Second, against which Beard passionately warned. William Appleman Williams, although he shared many of Beards political instincts, was otherwise a very different kind of historian, who did not so much look at the material interests underlying the dynamic of American expansion, as at the rival ideals whose conflict he took as a guiding thread for understanding the history of the nation. Originally, the Pilgrim Fathers had brought the vision of a Christian Commonwealth to the New Worldan

reviews

gowan: Imperial America

149

egalitarian community of small producers, whose values had never altogether disappeared, taking in later times the form of an ethical socialism. But from the Revolution onwards, an alternative vision of Americas future had developed and for the most part dominated: the construction of a vast continentaland eventually overseasempire, in which big money and hubristic ambition would thrive, under cover of fair-sounding liberal ideals of free trade and competition for all. The Contours of American History, Williamss major work, traces a counterpoint between these incompatible outlooks down into the epoch of the Cold War. The global battle against Communism was just the latest way in which America sought to escape abroad from the calling of what Williams believed was its true, moral self at home. For Bacevich, each historian got the immediate political agenda of his time wrong. Beard was mistaken in opposing us entry into the Second World War, which was necessary to destroy fascism, just as Williams failed to see that it was essential to defeat Communism. But both were right in thinking that something more long-standing was at work in these conflicts. Encompassing these just causes was a larger and less attractive set of objectives, which has outlived them. Bacevich himself, as an heir to Beard and Williams, draws on different sides of their work. His tough-mindedness, of tone and judgement, descends from Beard. But his methodological focus is in many ways closer to Williams. American Empire does not dwell much on the nexus between internal social interests and external power-projection. Nor does it explore the mechanics of grand strategy, in the style of Gabriel Kolko, whose name is absent from the genealogy of critics Bacevich invokes, but whose worksfrom The Triumph of Conservatism to The Politics of War to The Limits of Power and beyondrepresent the other major corpus of critical history and theory of imperial America, the largest of all. There could be a cultural reason for this: Kolko, based in Canada, has never shown the same attachment to popular us values as Beard or Williams. At all events, it could be argued that the selection of legacies Bacevich has made among his forebears limits the way he stages his analytic narrative. In particular, what is not covered here are what could be called the Achesonian foundations of post-war us imperial strategy. For, as Bruce Cumings and others have shown, the turn to a huge power-projection outwards, fuelled by a very large, permanent defence industry and massive military budget, and codified doctrinally in nsc-68, occurred against the background of a serious recession in the American economy in 1949, and still high levels of union militancy. It was then, as Acheson put it, that Korea saved us. The Cold War delivered a range of key domestic benefits: warfare Keynesianism as a strong alternative to and barrier against welfare Keynesianism; a powerful anti-Communist ideology for use against any form of radical dissent; a means

reviews

150

nlr 21

of providing a range of R and D and other supports to a wide spectrum of us industries; and very powerful, cross-class social constituencies in the us with a direct stake in imperial expansion. It is arguable that something similar may have been at work in the steady escalation of us financial, mercantile and military operations since the end of the Cold War. Beginning with the Gulf War under the first Bush, expanding continuously under Clinton, and now speeding up under the second Bush, the combination of American arms and arm-twisting have enforced Washingtons writ across ever wider areas of land and life beyond the oceans, at a time when the stresses of enormous social polarization at home might otherwisewith the demise of the Evil Empirehave led to pressures for domestic reform and redistribution. Bacevich does not pursue this Beardian line of analysis, but focuses instead on the ideology and instruments of the new, post-Cold War imperialism. Following Williams, Bacevich insists that the empire did not just grow like Topsy: it was the outcome of a particular world view and was built by a coherent strategy, which gained support from the American people. The key to both has been the euphemism liberal internationalismcodewords for forcing the world open to American enterprise, backed by American power. But if the terrain is that of Williams, the vision is more caustic. His treatment of globalization, one of the great mantras of the current period, is characteristic. While it is probably no exaggeration to say that tens of thousands of academics around the world have treated the latter as a kind of new world-historical dawn, rendering obsolete much of the entire canon of the social sciences, Bacevich suggests that it can be read as both more parochial and more long-standing. The American economic expansionism that used to be expressed as interdependence has been rebaptized: globalization is essentially a radicalized synonym for this older term. These are concepts that face both inwards and outwards: inwards to convince the American population of the need for economic expansion abroad rather than social transformation at home; and outwards to legitimate the drive to open other territories and markets to American business. How near one to the other is every part of the world. Modern inventions have brought into close relation widely separated peoples and made them better acquainted . . . Distances have been effaced . . . The worlds products are being exchanged as never before . . . Isolation is no longer possible or desirable. Anthony Giddens? No, McKinley in September 1901. Or, as Thomas Friedman put it a century later: Globalization-is-Us. One of the great merits of American Empire is that it makes clear how seamlessly continuous the doctrines of American supremacy have been. Those who fondly imagine there has been some major break with the recent past with the arrival of the current Republican incumbent of the White House are in for a shock from these pages. In the course of demonstrating

reviews

gowan: Imperial America

151

the key organizing concepts of imperial expansion and the discursive codes expressing them, Bacevich brings home with great cumulative force the fact that they have been held in common by Republican and Democrat leaders and presidents. Relentlessly, Bacevich piles quote upon quote from both sides of the party divide on all the key issues to demonstrate that the idea of bipartisanship is, if anything, too weak for the degree of identity between them. The anathemas against the dangers of isolationism, the inevitability and irreversibility of globalization, the centrality of market openness, the indispensability of American leadership for the security of the worldall these tropes are repeated indistinguishably by Republicans and Democrats alike. In this ideology, there is the characteristic slide back and forth between objective and subjective forms of legitimation. Globalization is a historical inevitability that must be accepted. Yet the United States is the author of history, as Madeleine Albright explained, without whose protective might it would be at risk. Bacevich is right to stress that, in fact, the most complete and fulsome versions of Americas imperial mission in the world were the work of the Clinton regime, which wove its necessary internal and external, economic and military-political dimensions into a smooth whole after the rather lame efforts of its predecessor. He also has no difficulty showing that while the current Bush administration has discarded some of the rhetorical dcor of the Clinton years, the basic concepts and goals of American foreign policy remain unchanged. American Empire does more than offer an extraordinary granary of the ruling discourse, which anyone interested in the ideology of us power should read. In chapter after chapter Bacevich documents the twin tracks of expansionism in the 1990s: on one side, the opening of overseas economies and refashioning of financial institutions to us advantage, with the requisite cultural trappings; on the other, the projection of military force to keep or restore order abroad, accompanied by diplomatic strategies to discipline the other main power centres of the world. But in laying out this overall design, Bacevich devotes special attention to the area of his own professional expertise. His most original and valuable contribution to our understanding of the modus operandi of the Empire lies in his analysis of its military apparatus and the purposes to which this is now put. In a striking account, Bacevich argues that the Pentagons principal task today is closer to British gunboat diplomacy of the 19th century than to the conventional land wars of continentalprincipally Franco-German descent. For what are essentially policing operations in peripheral zones, the Department of Defence has developed 21st century equivalents of both gunboats and Gurkhasthat is, a combination of overwhelming air power with surrogate or mercenary forces on the ground: missiles, drones and

reviews

152

nlr 21

b-1s above, and the kla, Northern Alliance and Kurds below. Designed to minimize American casualties, which might unsettle domestic opinion, this two-pronged strategy does not exclude the use of us infantry, where needed: an imperial armed force that has absolutely no capacity to die is hardly adequate even for the clinical operations of a post-modern Empire. It is worth remembering that the gap in military technology between the us army and Iraqi resistance has been greater than that between the British military and the Zulus at the end of the 19th century. A handful of losses suffered in such unequal combat can even serve a purpose, since it is in the American states interest to resocialize its population into accepting some level of battlefield casualties. In cases where these risk breaching a low ceiling, air power can always be called in to flatten the landscape instead. To date, the limitation of this kind of empire lies in its unwillingness to shoulder direct colonial administration of conquered territories for any length of time. Here it has so far needed the help of satrapies, in un or Allied guise, to carry out routine duties, confining its own role to strategic control and direction. Such delegation is the more necessary, the greater the frequency of gunboat operations. In 1999, Bacevich points out, the us Commission on National Security reported that since the end of the Cold War, the United States has embarked upon nearly four dozen military interventions . . . as opposed to only 16 during the entire period of the Cold War. Gunboat diplomacy is not, of course, the only role for the American military. They must also maintain full spectrum dominancethat is, decisive strategic superiority over all other major powers, to deter them from seeking to balance against the United States. Armed vigilance on this scale has spawned an intercontinental network of what Bacevich terms proconsular powers, located in the four great regional commands, each presiding over vast swathes of earth, sky and water: cincpac (East Asia) headquartered in Hawaii; cincsouth (Latin America) in Miami; cinceur (Europe, Africa, Israel) in Brussels; and cincent (Middle East, Central Asia, the Horn) in Tampa. The commanders-in-chief of these theatres typically wield, Bacevich shows, far more political and diplomatic power than any corresponding civilian functionaries of the American state, and expect to be treated as what they areproconsuls of a global empire, invested with vast resources and powers. The staffs of the European, Central and Pacific Commands each exceed the size of the Executive Office of the President. At Southern Command, the smallest of the four, the staff consists of approximately 1,100, while over the 1990s their combined budgets rose from $190 million to $381 million, with figures adjusted for inflation. This militarization of the us outreach into the world, whose long-term effects on the shaping of American policy towards it have yet to be seen, is not exempt from its own contradictions.

reviews

gowan: Imperial America

153

Bacevich shows the way in which the loquacious and incompetent cinceur commander in charge of the Balkan War, Wesley Clark, had to be sidelined by his superiors in Washington, before retiring to the obsequious attentions of Michael Ignatieff and the honours of studio commentary on cnn. Bacevichs book is a level-headed, disciplined exercise. It does not attempt, in the fashion of so much current literature on us foreign policy, to offer half-cocked theories of international relations, the world economy, popular culture, the wonders of electronic technology, or the vagaries of the domestic political system. It sets itself a carefully limited brief: to show the practical and ideological continuities of American imperial power, and the novel military dispositions it has developed since the Cold War. In these aims, it succeeds admirably. Coolly and succinctly, it dismantles most of the mystifications currently surrounding the us imperium. It is to be hoped there will be a rapid translation into Arabic.

reviews

The Consumer Trap

Big Business Marketing in American Life

MICHAEL DAWSON

Michael Dawsons meticulous and illuminating research into marketing theory and practice lays bare some of the most important developments of the twentieth century: the ways in which the sophisticated and self-conscious class coercion designed by and for business leaders passed beyond meticulous management of the workplace to manipulating peoples off-the-job perceptions and actions. Noam Chomsky

The History of Communication

Hardcover, $26.95

800-537-5487 www.press.u

.edu

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The US Foreign Policy Establishment and Grand Strategy: How American Elites Obstruct Strategic Adjustment - Christopher LayneDocument16 pagesThe US Foreign Policy Establishment and Grand Strategy: How American Elites Obstruct Strategic Adjustment - Christopher LaynepeterVoterNo ratings yet

- The Globalization Gamble: The Dollar-WallStreet Regime and Its Consequences - Peter GowanDocument121 pagesThe Globalization Gamble: The Dollar-WallStreet Regime and Its Consequences - Peter GowanpeterVoterNo ratings yet

- Neo-Liberal Theory and Practice For Eastern Europe - Peter GowanDocument58 pagesNeo-Liberal Theory and Practice For Eastern Europe - Peter GowanpeterVoterNo ratings yet

- The Gulf War, Iraq and Western Liberalism - Peter GowanDocument42 pagesThe Gulf War, Iraq and Western Liberalism - Peter GowanpeterVoter100% (1)

- Western Economic Diplomacy and The New Eastern Europe - Peter GowanDocument22 pagesWestern Economic Diplomacy and The New Eastern Europe - Peter GowanpeterVoterNo ratings yet

- It's Over, Over There: The Coming Crack-Up in Transatlantic Relations - Christopher LayneDocument23 pagesIt's Over, Over There: The Coming Crack-Up in Transatlantic Relations - Christopher LaynepeterVoterNo ratings yet

- The Polish Vortex - Peter GowanDocument44 pagesThe Polish Vortex - Peter GowanpeterVoterNo ratings yet

- The Third Round in Poland - Peter GowanDocument40 pagesThe Third Round in Poland - Peter GowanpeterVoterNo ratings yet

- The Origins of The Administrative Elite - Peter GowanDocument31 pagesThe Origins of The Administrative Elite - Peter GowanpeterVoterNo ratings yet

- U.S. Hegemony Today - Peter GowanDocument12 pagesU.S. Hegemony Today - Peter GowanpeterVoterNo ratings yet

- Eastern Europe, Western Power and Neoliberalism - Peter GowanDocument12 pagesEastern Europe, Western Power and Neoliberalism - Peter GowanpeterVoterNo ratings yet

- A Spanish Singleton - Peter GowanDocument6 pagesA Spanish Singleton - Peter GowanpeterVoterNo ratings yet

- PAX EUROPÆA - Peter GowanDocument9 pagesPAX EUROPÆA - Peter GowanpeterVoterNo ratings yet

- American Global Government: Will It Work? - Peter GowanDocument39 pagesAmerican Global Government: Will It Work? - Peter GowanpeterVoterNo ratings yet

- The Waning of U.S. Hegemony-Myth or Reality? A Review Essay - Christopher LayneDocument27 pagesThe Waning of U.S. Hegemony-Myth or Reality? A Review Essay - Christopher LaynepeterVoter100% (1)

- War in The Contest For A New World Order - Peter GowanDocument15 pagesWar in The Contest For A New World Order - Peter GowanpeterVoter100% (1)

- A Salutary Shock For Bien Pensant Europe - Peter GowanDocument6 pagesA Salutary Shock For Bien Pensant Europe - Peter GowanpeterVoterNo ratings yet

- WHERE IS THE EAST? Amrita GhoshDocument7 pagesWHERE IS THE EAST? Amrita GhoshremipedsNo ratings yet

- Lea2 Topic13Document18 pagesLea2 Topic13ChristianJohn NunagNo ratings yet

- UGC - NET With MCQ (English)Document145 pagesUGC - NET With MCQ (English)Preeti BalharaNo ratings yet

- Avignam Company Profile - August 2011Document3 pagesAvignam Company Profile - August 2011Abhilash PuljalNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1 - Understanding GlobalizationDocument18 pagesLecture 1 - Understanding GlobalizationdomermacanangNo ratings yet

- Peter Lang Film Studies 2013Document92 pagesPeter Lang Film Studies 2013prisconetrunner67% (3)

- The Manager of The 21st CenturyDocument35 pagesThe Manager of The 21st CenturySheni Snaptu100% (1)

- Pat Mcfadden On Postcoloniality in The NorthDocument16 pagesPat Mcfadden On Postcoloniality in The Northevolvepast8No ratings yet

- Faculty Based Bank Written SolutionDocument127 pagesFaculty Based Bank Written SolutionOvimani Shan100% (1)

- Steger Manfred The Political Dimension GlobalizationDocument13 pagesSteger Manfred The Political Dimension GlobalizationSharmaine GantanNo ratings yet

- Economic Globalization, Poverty, and InequalityDocument5 pagesEconomic Globalization, Poverty, and InequalityJude Daniel AquinoNo ratings yet

- A Resource Manual On Reducing Enmity: Nemy MagesDocument75 pagesA Resource Manual On Reducing Enmity: Nemy MagesSvetlanaNo ratings yet

- Jain (2003) Local Political Leadership in Japan A Harbinger of Systemic Change in Japanese PoliticsDocument30 pagesJain (2003) Local Political Leadership in Japan A Harbinger of Systemic Change in Japanese PoliticsFiamma LarakiNo ratings yet

- Modern - Civilisation 2 LatestDocument10 pagesModern - Civilisation 2 LatestmubeenNo ratings yet

- Thomas Hylland Eriksen - GlobalizationDocument15 pagesThomas Hylland Eriksen - Globalizationbilal.salaamNo ratings yet

- Location Facilities QuizDocument29 pagesLocation Facilities QuizDiane CabiscuelasNo ratings yet

- Chapter 16 "Global Strategy: An Organizing FrameworkDocument29 pagesChapter 16 "Global Strategy: An Organizing FrameworkMohamdDerpawiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Introduction To International BusinessDocument84 pagesChapter 1 Introduction To International Businesskishore.vadlamaniNo ratings yet

- GlobalisationDocument22 pagesGlobalisationdivyamittalias100% (3)

- 8 Theories of Globalization - Explained!Document31 pages8 Theories of Globalization - Explained!frustratedlawstudentNo ratings yet

- Inequality and Economic Policy: Essays in Memory of Gary Becker, Edited by Tom Church, Chris Miller, and John B. TaylorDocument42 pagesInequality and Economic Policy: Essays in Memory of Gary Becker, Edited by Tom Church, Chris Miller, and John B. TaylorHoover InstitutionNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Global Business Today 11th by HillDocument36 pagesTest Bank For Global Business Today 11th by Hillamplywidenessbwjf100% (44)

- Ö. Burcu Özdemir Sarı, Suna S. Özdemir, Nil Uzun - Urban and Regional Planning in Turkey - Springer International Publishing (2019)Document291 pagesÖ. Burcu Özdemir Sarı, Suna S. Özdemir, Nil Uzun - Urban and Regional Planning in Turkey - Springer International Publishing (2019)Bun NyNo ratings yet

- Globalization Research Paper Thesis StatementDocument5 pagesGlobalization Research Paper Thesis Statementhfuwwbvkg100% (1)

- GlobalizationDocument24 pagesGlobalizationKate NguyenNo ratings yet

- wbs14 01 Rms 20240307Document15 pageswbs14 01 Rms 20240307balgacium.marketerNo ratings yet

- CH 16 - Collective Behavior and Social Change - NotesDocument83 pagesCH 16 - Collective Behavior and Social Change - Notesamnahbatool785No ratings yet

- MCC385B Assignment For Culture or GlobalisationDocument6 pagesMCC385B Assignment For Culture or GlobalisationMyat ThuNo ratings yet

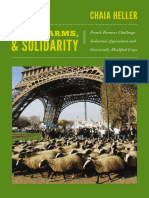

- Food, Farms, and Solidarity by Chaia HellerDocument52 pagesFood, Farms, and Solidarity by Chaia HellerDuke University PressNo ratings yet

- OECD - 2001 - Towards A New Role For Spatial PlanningDocument166 pagesOECD - 2001 - Towards A New Role For Spatial Planningmar laNo ratings yet