Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Paradox of Managing Brand Communities

Uploaded by

Hammad Bin Azam HashmiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Paradox of Managing Brand Communities

Uploaded by

Hammad Bin Azam HashmiCopyright:

Available Formats

16

The Paradox of Brand Community Management

Brand communities, while hot and fundamental in the relationship interactive marketing age, are often seriously misunderstood. Located at the pinnacle of the loyalty continuum, true communities possess social structure and exhibit socialization processes. These sociological facts must be thoroughly understood by any manager who claims community goals for his or her brand. HarleyDavidson frequently admired for its ability to generate an almost religious loyalty to its brand has developed a deep appreciation of the power of brand communities that personally link consumers together and is eager to manage them successfully. The present article, evolved from the Harvard Business School study case on the Harley-Davidson Posse Ride, deals with the management challenges and tensions that may arise when building brand communities.

Prof. Susan M. Fournier Visiting Associate Professor of Business Administration, Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth College, US-Hanover

lic. sc. com Kathrin Sele Doctoral Candidate at the Institute of Marketing and Retailing at the University of St.Gallen, CH-St.Gallen

Prof. Dr. Marcus Schgel Assistant Professor at the University of St.Gallen and Head of the Competence Center Distribution and Co-operation at the Institute of Marketing and Retailing, CH-St.Gallen

1. The Notion of Brand Community

Harley Owners Group (HOG) and the Posse Ride

In 1983 Vaughan Beals, member of the management board, decided with some other colleagues to found the Harley Owners Group (HOG), a factory-sponsored motorcycle enthusiast club. HOGs intention was to foster customer loyalty, enhance the Harley-Davidson lifestyle experience, deepen brand relationships, and, primarily, bring the company closer to its consumers. The club is open to all Harley-Davidson owners and a free one-year membership is included with the purchase of every new motorcycle. As of year end 2004, international HOG membership was close to one million riders who gathered to meet other riders, develop social ties, participate in community service, and, most importantly per the HOG mantra, to ride and have fun. HOG provides its members with ongoing information and leadership training, as well as a vibrant portfolio of national and local rallies and other brand events. The agship rolling rally was introduced in 1997 in the form of the rst Posse Ride. Characterized by spontaneity and a sense of momentousness, roughly 250 hard-core Harley enthusiasts gathered for the rst Posse and rode more than 2000 miles together, coast-to-coast from Portland, Oregon to Portland, Maine. Now cult-like in its attraction, Posse Rides have been creating bonds among Harley fans every year since. Communities are complex and dynamic socio-cultural entities. They possess different temporal dimensions, ranging from stable and enduring to temporary and periodic (McAlexander/Schouten/Koenig 2002, p. 40). First and foremost, the notion of community implies relationships within a group who shares a common connection, in this case with the brand and the aggregated consumption activity. Brand communities share an ethos and a set of values leading to a sense of moral responsibility and duty towards one another as well as towards the brand (Muniz/OGuinn 2001). They exhibit hierarchies of membership status and processes for advancement within this social structure. Shared rituals and traditions, the use of common language, and the presence of signs and symbols signifying group membership

Seite 16 bis 20

3.2005

The Paradox of Brand Community Management

17

and status provide the cultural glue. Strong in- and out-group boundaries (a consciousness of kind) are the basis of a true brand community. The intrinsic connection that members feel towards one another often causes a critical demarcation between users of one brand and users of other brands in response (Muniz/OGuinn 2001, p. 413). Harley-Davidson community members, for example, typically eschew Japanese Rice Burners, while those in the Apple community explicitly and vocally detest IBM. The emotional bonds that emerge in a brand community become a crucial element in consumers personal identication with the brand and its surrounding environment. As a consequence, brand community members are often characterized by symbolic consumption behaviors proving their emotional attachment and commitment to the brand. As the above description makes clear, the concept of brand community is quite different from and, in a sense, much bigger than the notion of lifestyle brands or value segments. A common choice of a branded lifestyle (for example, Ralph Lauren) does not make a true community, which requests from its community members a clear devotion to the brand and its social system that is sincere and for the right reason (Muniz/OGuinn 2001, p. 419). As Muniz and OGuinn (2001, p. 413) say, community became more than a place. It became a common understanding of a shared identity. Community thrives only at the intersection of high centrality of the brand and consumption activity and strong social ties. Without the strong social ties, community dissolves into simple brand loyalty; without centrality of the brand and consumption activity, community manifests itself in minglers and brand tourists. Brand communities are indeed special and rare, and, consequently, not every manager has the right or ability to claim brand community goals. The socio-cultural essence required of true community highlights certain enabling factors for community development: an experience-driven, social center of gravity for the brand, in which brand value is

The Paradox of Brand Community Management

demonstrated by the product or service in use; highly visible (versus private) consumption activity; and recognized cultural capital in the brand as badge. And, perhaps most importantly, communities take an inordinate amount of work, requiring commitments of time and resources that not many companies are prepared or willing to make. Brand communities are not just about consumer bonds. For companies they are explicitly commercial and crucial for the establishment of brand equity by inhering a strong and sustainable differentiation potential that supports the creation and preservation of competitive advantage long-term based on a strong brand (Aaker/Joachimsthaler 2000, p. 88).

2. Fundamental Management Challenges

Because of its role in strengthening brand equity and consumer loyalty, brand community management must be considered a long-term strategic task within the brand management process (Aaker/Joachimsthaler 2000: internal cover). In this sense, an ongoing and temporally-sensitive evaluation, not only of community benets but also of potential risks that arise in their capture, becomes fundamental. Consumer loyalty is a complex relational process that evolves, builds, and develops dynamically over time: a process driven by

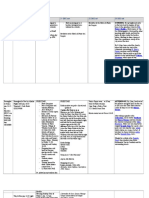

meaningful customer-centric experiences that allow consumers to develop the necessary connections and strong bonds of satisfaction and commitment (Mc Alexander/Kim/Roberts 2003). Strong community relationships are actually built on four different levels: between the consumer and the product, between the consumer and the brand, between the consumer and the rm, and, of course, between consumer and consumer. The more each relationship is internalized as part of the customers life experience, the more the customer is integrated into the brand community and the more loyal the customer is in consuming the brand (McAlexander/ Schouten/Koenig 2002, p. 48). The Harley-Davidson Posse Ride offers an excellent example of a community building tactic that effectively strengthens and cements bonds on all four of these levels (Figure 1). One of the main challenges when managing brand communities that arises from this multi-faceted relational context is the creation of an adequate relationship marketing environment on all levels that ts the brand, the branded product or service as well as the image perceived by the consumer (Kapferer 1997, p. 94). The different levels also need to be managed separately as well as in reliance to one another to fully exploit the power of community bonds. According to Fournier (1998), brand relationship quality, based on the reciprocity principle on which all relation-

Brand The rally offers settings that enhance core brand associations such as camaraderie, freedom, adventure, discovery, irreverence, the purchase of Harley branded goods, and that extend brands reaches into consumers lifestyles.

Product The ride fosters enthusiasm for the sport of motorcycling, supports the customers riding habits, provides challenges and peak experiences to increase their commitment, and to deliver a lifetime experience.

Focal Customer The journey fosters the cultivation and development of social processes and links riders together by taking part in shared rituals, events, and activities and by supporting one another through the challenges and crisis that arise. Customer Riding side by side with consumers gives managers an incomparable opportunity to get to know them first, to find out what matters to them, and to deepen the collaboration especially regarding future product developments. Marketer

Fig. 1: Customer-centric Model of Brand Community applied to the HOG Posse Ride (Source: according to McAlexander/Schouten/Koenig 2002, p. 39)

Seite 16 bis 20

3.2005

18

ships are grounded, evolves through meaningful brand/company and consumer actions. Everything the company or brand does in the context of the community setting therefore has the potential to dene and rene the community relationship. Quite unlike the controlled context offered within a 30-second television advertisement, brand community enactment presents a rather chaotic and complex meaning-making picture, wherein hyper-vigilance is required regarding meanings desired and meanings-made. The unique and distinctive evolutionary character of brand community relationship development also requires management exibility and mutability while simultaneously striving for continuity and consistency in the overall brand positioning and communication. Cultivating a long lasting symbiotic relationship within the community is a crucial yet complicated and delicate management task (Schouten/McAlexander 1995, p. 57). Another important challenge involved in brand community management stems from their genesis and ownership status. Brand communities are created and hence owned by the consumers and cultures that comprise them. Communities come into existence as consumers collectively identify with symbolic goods and activities whose brand meanings fulll their needs. The role of the marketer in the community is therefore that of an enabler: a function that can be more or less visible, powerful and manifested. Because devoted fans and loyal consumers invest much more of themselves in their consumption in community settings, they also exhibit higher expectations and a clearer understanding on when, how, and whether they want to be addressed by the marketer at all (Kozinets 2001, p. 85). Management must take special care to ensure that they do not touch or tamper with community social structure in domineering, overwhelming, or unexpected ways when trying to protect their relationship investments. They must be hyper-critical of interventions that disrupt the authenticity of the social system at play. The paradox here is that the more distinct or strong the mea3.2005

nings underlying the culture and hence the greater the interest the marketer has in managing it, the greater the interest the consumer has in maintaining ownership. Thus brand managers are often forced into the high-risk situation where they must hand the brand community over into the hands of the customers who feel strongly related to it (Muniz/OGuinn 2001, p. 415). In its extreme, brand community management becomes an oxymoronic term.

3. Reducing Tensions when Managing Brand Communities

Brand-oriented companies have an obvious interest in inuencing and developing brand communities characterized by overwhelming loyalty rates and strong relationship bonds that function as exit barriers for customers (McAlexander/Schouten/Koenig 2002, p. 50). Concurrently, the strong emotional and behavioral attachments exhibited by brand community members drive high expectations regarding the experiences that they anticipate. Management is thus confronted with several tensions, the careful balance of which is critical to successful involvement in the community setting. The following outline of management tensions inherent in brand community development is based upon ndings from the HarleyDavidson Posse Ride, though application of these principles to other geographically and non-geographically bound communities should prove sound.

Fragmentation vs. Unity

Brand communities unite people that have a common interest in a product and brand, but possibly not more than that. Community members often reveal distinct socio-economic, geographical, gender, and age differences suggesting potential community fragmentation, especially when physically participating in an event. The question that arises is whether or not these differences have an implication in the notion of a unied brand community. The Posse Ride, for example, provides a way to meet people

The Paradox of Brand Community Management

who share a common bond of uniqueness within the social rider hierarchy. However, the Harley-Davidson Motor Company has evolved over these recent years into a more global and mainstream player with a much broader customer group spanning a range of different subcultures. If the company aims to foster brand community, it should legitimately encourage one large community instead of several small ones, and minimize group differences in order to stress common interests among riders. A major challenge thus presents itself in integrating several disparate but equally important groups, such as, for example, outlaws and mainstream consumers, or authentic riders and so-called Yuppie weekend warriors. On the one hand, events, forums, and other communityenabling mechanisms allow the company to broaden its consumer base and thereby enlarge the community; but, on the other hand, this very expansion portends fundamental changes that may ultimately diminish the appeal of community belonging itself. At what point does management acknowledge the fragmentation of its brand culture? When do the parts matter more than the whole? Astute community management requires reection of the culturally-situated character of the community membership so consumers do not turn against the brand. Critical also is recognition of the fact that some sub-cultures give the brand its mystique, legitimacy, and authenticity (e. g., the outlaws) while others give the company its protability in recognition of these meanings-made (Schouten/McAlexander 1995, p. 59). Care must be taken to balance these meaning creation and reinforcement processes among the multiple players in the system as well.

Structure vs. Chaos

Community managers are also faced with an ongoing question of imposing structure, embracing chaos, or cycling sporadically between both. While management structure may logically seem to imply better value capture, the irony is that the more management tries to structure the community development process, the less a community it

Seite 16 bis 20

19

becomes. On the side of the argument in favor of structure, however, consumers need certain guidelines so that they do not get lost within the social context being established. Acutely aware of this, HOG managers favor a loose structure conducive to spontaneity and co-creation, and a relaxed, hands-off style. They are adamant about avoiding corporate interventions that might cause routine or predictability and impair the spirit of adventure that characterizes the Posse experience. But this hands-off attitude can be misinterpreted. Some Posse Riders feel that HOG management is unavailable, invisible, or simply not attentive enough to the diverse needs of the crowd. Since the consumerrm bond stands as an important community relationship goal, management is continually confronted with this difficult balancing decision.

ment. But, as we all know, not everyone is equally capable in cultivating intimate friendship bonds, nor can all those capable deliver on the reciprocation that true intimacy entails. Community managers must think through exactly how they want to become close to their customers, and who within the organization is capable of performing which closeness roles. A community randomly and opportunistically populated with rm employees seeking simply to become close-to-their-customers in essence sets itself up to fail.

Accelerate acculturation of commu

nity members into the social status system Provide tools and markers for identity expression and advancement within the social system: facilitate accrual of status and cultural capital in the system Fuel the brand mystique that serves the foundation on which community is built Respect and understand the brand heritage and support core brand meaning throughout the community marketing mix Say no to branding opportunities that dilute brand meanings and erode community foundations of the brand Provide opportunities for community interaction: put consumers in close contact with each other, put consumers in close contact with the rm Adopt a close-to-the-consumer strategy capable of granting the true intimacy that community bonds entail Balance the tensions of community growth versus maintenance, as community boundaries are expanded, and core users are compromised Evaluate the community against relationship-relevant metrics

Marketing vs. Authenticity

Most of the issues noted above can be summarized in the marketing versus authenticity tension which incorporates the tightrope walk that management faces in its community development task. Most characteristically, this question manifests itself in issues of credibility: How can management be deeply loyal to both consumer and company goals? Can the manager simultaneously perform as community advocate and champion of company goals? In the community management game, can you play defense and offense at the same time? Successful brand communities will always attract the attentions of management seeking to leverage them more fully so as to capture more value for the rm. And, it is in this, the ultimate paradox, that success breeds failure, for the community that is tampered with is quickly destroyed. We have said that communities are largely the property of the consumers and cultures that create them. The marketers role in the community is much more limited and subtle than one would desire or expect. In this context community managers should focus on ways in which their activities can facilitate and enable the culture, while avoiding interventions that might destroy its core. In the words of HOG Senior Vice President Michael Keefe: My job is to hold the ame, and not put it out ... in essence, to not screw it up. As a consequence, marketers should:

Empathy vs. Intimacy

Events, online forums, and other community platforms bring consumers and managers together in a friendly and unconventional setting and provide ongoing opportunities for serendipitous listening, learning, and exchange. This engagement in dialogue offers enormous added value to the consumer as well as to the company (Gob 2001, p. 262). Community therefore uniquely enables close-to-the-customer interaction: a much sought-after opportunity in todays overwhelming marketing world. Thus confronted with an invaluable amount of ethnographic qualitative data, the challenge for community managers becomes one of developing true intimacy with consumers, versus simple empathy concerning their affairs. Intimacy and empathy are of course both valuable. The empathy approach assumes that if managers can think and act as if they were consumers, then their marketing and product decisions will be better informed. Intimacy, however, as it characteristically exists within the context of friendship, is ever more powerful than that. In the reciprocating friendship relation, each partner shares a deep and complete knowledge of the other. Intimacy thus forms the basis for trust, which propels relationship developThe Paradox of Brand Community Management

Enable the social life of the brand Facilitate socialization of new users so

that the community may further develop

Seite 16 bis 20

As mentioned above, brand community demands an unusual amount of patience, hard work, and devotion on the part of the company. Unfortunately, many companies desirous of community benets have been unwilling to invest the necessary and involved labor to gain them. These companies impose surfacelevel tools that suggest effective community management. Some hire agencies to conduct sensitive community building functions, or even outsource the entire community building process. Others delude themselves into thinking that community can be bought through fun experiences and events. Operating with a driving goal of profit maximization rather than relationship-building toward that ultimate end, these best practices jeopardize the very concept of the brand community for other, more dedicated and enlightened managers. As soon as marketers start to see commu3.2005

20

nity as a commercial property that exists only to be exploited (Kozinets 2001, p. 82), customers begin their turn away from the brand. But, brand community members define success quite differently than does the marketer (Muniz and OGuinn 2001, p. 419). Managers must walk the fine line between commercial marketing activity and credible authenticity when solving this equation for the brand.

4. Conclusion

Brand community meaning making is an inherently uncontrollable process driven as much if not more by the cultures and consumers that own them. The good news is that some lucky brands become a part of the cultural symbol system and thus can claim benets of community for the rm. The bad news is that once a brand becomes a part of the cultural symbol system, any consumer can use it in any way. And, the more distinct or strong the cultural meanings, the greater the interest the consumer has in owning and managing them. The managements role when building brand communities should be a governing one in the sense of brand governance that does not over-engineer but rather secures continuity. Structures, cultures, people and systems need to be developed to support brand-building measures (Davis 2000, p. xii). Companies that seek to cultivate a brand community will have to confront the difficult decision of designing an effective and successful organizational structure to support and manage it. They could choose to build up a separate function such as with Harley-Davidsons HOG organization, or they could decide to run community as a part of the marketing department. A

separated group would have the advantage of offering a boundary function between consumers and the company that seeks to protect the delicate balance of marketing and authenticity at its core. But, at the same time, this situation, and the lack of organizational integration one of the key marketing concepts of the past years that it entails, creates its own conundrums. No solution is perfect, and each creates interest conicts as well as situation-specic advantages. An analysis of organizational processes that allow successful brand community building could surely be used to dene best practices in facing the tightrope walk between marketing and authenticity. At the end of the day, the goal of community is to turn the brand into an icon and its admiring customers into winners (Schouten/McAlexander 1995, p. 55). Of Harley-Davidson, Kunde (2002) says: Harley-Davidson is not just the most powerful motorcycle cult, it is also one of the most powerful religions if not the most powerful brand religion worldwide. Strong brand communities hold the power to create brand equity and brand loyalty long-term. If we can manage the ame.

References

Aaker, D. A./Joachimsthaler, E. (2000): Brand Leadership, New York. Davis, S. M. (2000): Brand Asset Management: Driving protable growth through your brands, San Francisco. Fournier, S. (1998): Consumers and Their Brands: Developing Relationship Theory in Consumer Research, in: Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 24, No. 4/1998, pp. 343373.

Fournier, S./Sensiper, S./McAlexander, J./Schouten, J. (2000): Building Brand Community on the Harley-Davidson Posse Ride, Harvard Business School Cases, Boston. Gob, M. (2001): Emotional Branding the new paradigm for connecting brands to people, New York. Kapferer, J. N. (1997): Strategic Brand Management: Creating and Sustaining Brand Equity long term, 2nd ed., London. Kozinets, R. (2001): Utopian Enterprise: Articulating the Meanings of Star Treks Culture of Consumption, in: Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 28, No. 1/2001, pp. 6788. Kunde, J. (2002): Corporate Religion. Building a strong company through personality and corporate soul, London. McAlexander, J. H./Kim, S. K./Roberts, S. D. (2003): Loyalty: The Inuence of Satisfaction and Brand Community Integration, in: Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice, Vol. 11 No. 4/2003, pp. 111. McAlexander, J. H./Schouten, J. W./Koenig, H. F. (2002): Building Brand Community, in: Journal of Marketing, Vol. 66, January 2002, pp. 3854. Muniz, A. M./Guinn, T. C. (2001): Brand community, in: Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 27, No. 4/2001, pp. 412432. Schouten, J. W./McAlexander, J. H. (1995): Subcultures of consumption: An ethnography of the new bikers, in: Journal of Consumer Research, No. 1/1995, pp. 4361.

T

3.2005

The Paradox of Brand Community Management

Seite 16 bis 20

You might also like

- Brand Communities - An EssayDocument2 pagesBrand Communities - An EssayGiridhar RamachandranNo ratings yet

- "Brand Community: Drivers and Outcomes." Journal of Psychology and Marketing.Document22 pages"Brand Community: Drivers and Outcomes." Journal of Psychology and Marketing.Nandya PanaseaNo ratings yet

- Executive SummaryDocument9 pagesExecutive SummarywontuckyNo ratings yet

- Citizen Brand: 10 Commandments for Transforming Brands in a Consumer DemocracyFrom EverandCitizen Brand: 10 Commandments for Transforming Brands in a Consumer DemocracyNo ratings yet

- Brand CommunitiesDocument22 pagesBrand Communitiesmadadam88No ratings yet

- The Power of Co-Creation: Build It with Them to Boost Growth, Productivity, and ProfitsFrom EverandThe Power of Co-Creation: Build It with Them to Boost Growth, Productivity, and ProfitsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- MA7 1 Tekst Tafra Za MADocument22 pagesMA7 1 Tekst Tafra Za MAfarahalim2310No ratings yet

- The Sincerity Edge: How Ethical Leaders Build Dynamic BusinessesFrom EverandThe Sincerity Edge: How Ethical Leaders Build Dynamic BusinessesNo ratings yet

- Brand Purpose As A Cultural Entity Between Business and Society, Gambetti-Biraghi-Quigley (2019)Document18 pagesBrand Purpose As A Cultural Entity Between Business and Society, Gambetti-Biraghi-Quigley (2019)Alice AcerbisNo ratings yet

- The Customer Advocate and the Customer Saboteur: Linking Social Word-of-Mouth, Brand Impression, and Stakeholder BehaviorFrom EverandThe Customer Advocate and the Customer Saboteur: Linking Social Word-of-Mouth, Brand Impression, and Stakeholder BehaviorNo ratings yet

- Brand Strategies How to Connect Consumer’s Experience And Marketing ProcessFrom EverandBrand Strategies How to Connect Consumer’s Experience And Marketing ProcessRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Brand Engagement With Brand ExpressionDocument27 pagesBrand Engagement With Brand ExpressionArun KCNo ratings yet

- The Stakeholder Strategy: Profiting from Collaborative Business RelationshipsFrom EverandThe Stakeholder Strategy: Profiting from Collaborative Business RelationshipsNo ratings yet

- How culture shapes consumer-brand relationshipsDocument17 pagesHow culture shapes consumer-brand relationshipsMaham QureshiiNo ratings yet

- Clicks and Mortar (Review and Analysis of Pottruck and Pearce's Book)From EverandClicks and Mortar (Review and Analysis of Pottruck and Pearce's Book)No ratings yet

- Wirtzetal JOSM2013 Online Brand CommunitiesDocument22 pagesWirtzetal JOSM2013 Online Brand CommunitiesKishore GabrielNo ratings yet

- HOG's Role in Developing Community & Loyalty for Harley-DavidsonDocument1 pageHOG's Role in Developing Community & Loyalty for Harley-DavidsonBharadwaja ReddyNo ratings yet

- Corporate Social Responsibility vs Creating Shared ValueDocument6 pagesCorporate Social Responsibility vs Creating Shared Valuebayu_pancaNo ratings yet

- Exploring Social Media Engagement Behaviors in The ContextDocument16 pagesExploring Social Media Engagement Behaviors in The ContextWassie GetahunNo ratings yet

- Brand Communities, Marketing, MediaDocument5 pagesBrand Communities, Marketing, MediaBao TruongNo ratings yet

- Building Strong Brands (Review and Analysis of Aaker's Book)From EverandBuilding Strong Brands (Review and Analysis of Aaker's Book)No ratings yet

- Just Good Business: The Strategic Guide to Aligning Corporate Responsibility and BrandFrom EverandJust Good Business: The Strategic Guide to Aligning Corporate Responsibility and BrandNo ratings yet

- Woisetschlager Et Al 2010 How To Make Brand Communities Work - Antecedents and Consequences of Consumer ParticipationDocument21 pagesWoisetschlager Et Al 2010 How To Make Brand Communities Work - Antecedents and Consequences of Consumer ParticipationDevanto ReigaNo ratings yet

- Dr. Shankar ChaudharyDocument8 pagesDr. Shankar ChaudharyAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- The Role of Brand in The Nonprofit Sector - Stanford Social Innovation ReviewDocument12 pagesThe Role of Brand in The Nonprofit Sector - Stanford Social Innovation ReviewGeorgianaYoungNo ratings yet

- The Membership Economy (Review and Analysis of Kellman Baxter's Book)From EverandThe Membership Economy (Review and Analysis of Kellman Baxter's Book)Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- How Purpose-Driven Brands Shape Consumer SocietyDocument6 pagesHow Purpose-Driven Brands Shape Consumer SocietyThya efeNo ratings yet

- A Building Brands TogetherDocument22 pagesA Building Brands TogetherPrameswari ZahidaNo ratings yet

- Getting Brand Communities RightDocument21 pagesGetting Brand Communities Rightmuhammadamad8930100% (1)

- Self-Branding, Micro-Celebrity' and The Rise of Social Media InfluencersDocument19 pagesSelf-Branding, Micro-Celebrity' and The Rise of Social Media InfluencersMilton Inostroza MuñozNo ratings yet

- Trust and Commitment Within A Virtual Brand CommunityDocument17 pagesTrust and Commitment Within A Virtual Brand CommunityCleopatra ComanNo ratings yet

- Values Management and Value Creation in Business: Case Studies on Internationally Successful CompaniesFrom EverandValues Management and Value Creation in Business: Case Studies on Internationally Successful CompaniesNo ratings yet

- Building Brand Community: James H. Mcalexander, John W. Schouten, & Harold F. KoenigDocument17 pagesBuilding Brand Community: James H. Mcalexander, John W. Schouten, & Harold F. KoenigSania MaudyNo ratings yet

- #Trending: A Guide To Social Media MarketingDocument76 pages#Trending: A Guide To Social Media MarketingTaylor OhmanNo ratings yet

- Counter-Brand and Alter-Brand Communities: The Impact of Web 2.0 On Tribal Marketing ApproachesDocument16 pagesCounter-Brand and Alter-Brand Communities: The Impact of Web 2.0 On Tribal Marketing ApproachesJosefBaldacchinoNo ratings yet

- Brand Perception and Revitalization StrategiesDocument6 pagesBrand Perception and Revitalization StrategiesGarima SharmaNo ratings yet

- Conversational Capital (Review and Analysis of Cesvet, Babinsky and Alper's Book)From EverandConversational Capital (Review and Analysis of Cesvet, Babinsky and Alper's Book)No ratings yet

- Brand personality as key to strong brand equityDocument12 pagesBrand personality as key to strong brand equityFazleRabbiNo ratings yet

- Crafting Luxury: Craftsmanship, Manufacture, Technology and the Retail EnvironmentFrom EverandCrafting Luxury: Craftsmanship, Manufacture, Technology and the Retail EnvironmentNo ratings yet

- Building Strong Brands in A Modern Marketing Communications Evironment - Keller-with-cover-page-V2Document19 pagesBuilding Strong Brands in A Modern Marketing Communications Evironment - Keller-with-cover-page-V2ashly rajuNo ratings yet

- Brand ActivismDocument13 pagesBrand ActivismTabitha MichaelNo ratings yet

- Getting Brand Communities RightDocument4 pagesGetting Brand Communities Rightmum830No ratings yet

- Accelteon Tribal MarketingDocument7 pagesAccelteon Tribal MarketingMike_Lagan4789No ratings yet

- Aligning Sustainability With Brand StrategyDocument3 pagesAligning Sustainability With Brand StrategyCindy JenningsNo ratings yet

- Researching Brands EthnographicallyDocument3 pagesResearching Brands EthnographicallyNazish SohailNo ratings yet

- The Power of Employee Resource Groups: How People Create Authentic ChangeFrom EverandThe Power of Employee Resource Groups: How People Create Authentic ChangeNo ratings yet

- The Social Licence for Financial Markets: Reaching for the End and Why It CountsFrom EverandThe Social Licence for Financial Markets: Reaching for the End and Why It CountsNo ratings yet

- Branded Communities in Sport ForDocument45 pagesBranded Communities in Sport Forfaseeh3335057No ratings yet

- Academic Writing Essay - Who Am I?Document6 pagesAcademic Writing Essay - Who Am I?Gabriela (Gabs)No ratings yet

- EMJ Cuomo Et Al 2009Document17 pagesEMJ Cuomo Et Al 2009Debora TortoraNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Social Media Marketing: By: Taylor OhmanDocument76 pagesA Guide To Social Media Marketing: By: Taylor OhmanTaylor OhmanNo ratings yet

- Branding The ManifestoDocument15 pagesBranding The ManifestocolinvandenbroekNo ratings yet

- Sustainability in Business: A Financial Economics AnalysisFrom EverandSustainability in Business: A Financial Economics AnalysisNo ratings yet

- Brand CultDocument16 pagesBrand CultBianca BbyNo ratings yet

- Advertising Paper 2, 2015Document2 pagesAdvertising Paper 2, 2015Hammad Bin Azam HashmiNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 - LS1001201Document13 pagesAssignment 1 - LS1001201Jamal Afridi100% (1)

- Internet and IT Applications in Selling and Sales ManagementDocument3 pagesInternet and IT Applications in Selling and Sales ManagementHammad Bin Azam Hashmi0% (1)

- Management: Introduction To Management and OrganizationsDocument28 pagesManagement: Introduction To Management and Organizationskoolkat87No ratings yet

- The Linkage Between Manufacturing Strategies and Strategic Human Resource Management Practices in MalaysiaDocument19 pagesThe Linkage Between Manufacturing Strategies and Strategic Human Resource Management Practices in MalaysiaHammad Bin Azam HashmiNo ratings yet

- Marketing Strategies: 1. Marketing PenetrationDocument2 pagesMarketing Strategies: 1. Marketing PenetrationHammad Bin Azam HashmiNo ratings yet

- Basic Math and AlgebraDocument296 pagesBasic Math and AlgebralenograNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 of MarketingDocument33 pagesChapter 3 of MarketingKzie RiveraNo ratings yet

- List of Urdu Sentences PDF Issb JuttDocument8 pagesList of Urdu Sentences PDF Issb Juttjutt1100% (3)

- Commercial Banks in PakistanDocument21 pagesCommercial Banks in PakistanzohroonNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Management PPT at Bec Doms Bagalkot MbaDocument34 pagesIntroduction To Management PPT at Bec Doms Bagalkot MbaBabasab Patil (Karrisatte)No ratings yet

- An Introduction To E-Business: Achieving Best Practice in Your BusinessDocument40 pagesAn Introduction To E-Business: Achieving Best Practice in Your BusinessHammad Bin Azam HashmiNo ratings yet

- Case AnswersDocument4 pagesCase AnswersHammad Bin Azam HashmiNo ratings yet

- Emerging MarketsDocument39 pagesEmerging MarketsHammad Bin Azam HashmiNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Strategic ManagementDocument46 pagesIntroduction To Strategic ManagementHammad Bin Azam HashmiNo ratings yet

- Modern Project Management: Student VersionDocument14 pagesModern Project Management: Student Versionvinay_krishna_1No ratings yet

- externalDocument31 pagesexternalHammad Bin Azam HashmiNo ratings yet

- Electronic Business in The: Electrical Machinery and Electronics IndustriesDocument75 pagesElectronic Business in The: Electrical Machinery and Electronics IndustriesHammad Bin Azam HashmiNo ratings yet

- Customer Satisfaction Surveys v1-0Document19 pagesCustomer Satisfaction Surveys v1-0Manish R ChughNo ratings yet

- FMCG and E Commerce: Assignment 3 Submitted by Raghav Mishra CS06B018Document4 pagesFMCG and E Commerce: Assignment 3 Submitted by Raghav Mishra CS06B018Hammad Bin Azam HashmiNo ratings yet

- Electronic Business in The: Electrical Machinery and Electronics IndustriesDocument75 pagesElectronic Business in The: Electrical Machinery and Electronics IndustriesHammad Bin Azam HashmiNo ratings yet

- The Quran-Based Human Resource Management and Its Effects OnDocument12 pagesThe Quran-Based Human Resource Management and Its Effects OnMuhammad Farrukh RanaNo ratings yet

- Media Cyberletter June 09 (2nd Version) PDFDocument4 pagesMedia Cyberletter June 09 (2nd Version) PDFHammad Bin Azam HashmiNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To E-Business: Achieving Best Practice in Your BusinessDocument40 pagesAn Introduction To E-Business: Achieving Best Practice in Your BusinessHammad Bin Azam HashmiNo ratings yet

- 443 1191 1 PBDocument31 pages443 1191 1 PBSayed Kamran NaqviNo ratings yet

- Challenges From Operating Environ PDFDocument5 pagesChallenges From Operating Environ PDFHammad Bin Azam HashmiNo ratings yet

- Nestley Report PDFDocument17 pagesNestley Report PDFmastoi786No ratings yet

- The Linkage Between Manufacturing Strategies and Strategic Human Resource Management Practices in MalaysiaDocument19 pagesThe Linkage Between Manufacturing Strategies and Strategic Human Resource Management Practices in MalaysiaHammad Bin Azam HashmiNo ratings yet

- Customer Satisfaction Questionnaire PDFDocument2 pagesCustomer Satisfaction Questionnaire PDFSadiq Sagheer100% (1)

- This Study Resource Was: ExercisesDocument1 pageThis Study Resource Was: Exercisesىوسوكي صانتوسNo ratings yet

- Method Statement For LVAC Panel TestingDocument9 pagesMethod Statement For LVAC Panel TestingPandrayar MaruthuNo ratings yet

- Example Italy ItenararyDocument35 pagesExample Italy ItenararyHafshary D. ThanialNo ratings yet

- Brochure of H1 Series Compact InverterDocument10 pagesBrochure of H1 Series Compact InverterEnzo LizziNo ratings yet

- CIGB B164 Erosion InterneDocument163 pagesCIGB B164 Erosion InterneJonathan ColeNo ratings yet

- Cryptography Seminar - Types, Algorithms & AttacksDocument18 pagesCryptography Seminar - Types, Algorithms & AttacksHari HaranNo ratings yet

- Private Copy of Vishwajit Mishra (Vishwajit - Mishra@hec - Edu) Copy and Sharing ProhibitedDocument8 pagesPrivate Copy of Vishwajit Mishra (Vishwajit - Mishra@hec - Edu) Copy and Sharing ProhibitedVISHWAJIT MISHRANo ratings yet

- Fayol's Principles in McDonald's ManagementDocument21 pagesFayol's Principles in McDonald's Managementpoo lolNo ratings yet

- Ethics, Governance and SustainabilityDocument408 pagesEthics, Governance and Sustainabilityshamli23No ratings yet

- MatrikonOPC Server For Simulation Quick Start Guide PDFDocument2 pagesMatrikonOPC Server For Simulation Quick Start Guide PDFJorge Perez CastañedaNo ratings yet

- University of Texas at Arlington Fall 2011 Diagnostic Exam Text and Topic Reference Guide For Electrical Engineering DepartmentDocument3 pagesUniversity of Texas at Arlington Fall 2011 Diagnostic Exam Text and Topic Reference Guide For Electrical Engineering Departmentnuzhat_mansurNo ratings yet

- Recent Advances in Mobile Robotics - TopalovDocument464 pagesRecent Advances in Mobile Robotics - TopalovBruno MacedoNo ratings yet

- Salesforce Platform Developer 1Document15 pagesSalesforce Platform Developer 1Kosmic PowerNo ratings yet

- M88A2 Recovery VehicleDocument2 pagesM88A2 Recovery VehicleJuan CNo ratings yet

- Britannia FinalDocument39 pagesBritannia FinalNitinAgnihotri100% (1)

- Soal Pat Inggris 11Document56 pagesSoal Pat Inggris 11dodol garutNo ratings yet

- Guideline 3 Building ActivitiesDocument25 pagesGuideline 3 Building ActivitiesCesarMartinezNo ratings yet

- QA InspectionDocument4 pagesQA Inspectionapi-77180770No ratings yet

- Educ 3 ReviewerDocument21 pagesEduc 3 ReviewerMa.Lourdes CamporidondoNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka Marketing ResearchDocument2 pagesDaftar Pustaka Marketing ResearchRiyan SaputraNo ratings yet

- Chapter FiveDocument12 pagesChapter FiveBetel WondifrawNo ratings yet

- Ceoeg-Cebqn Rev0Document3 pagesCeoeg-Cebqn Rev0jbarbosaNo ratings yet

- Desarmado y Armado de Transmision 950BDocument26 pagesDesarmado y Armado de Transmision 950Bedilberto chableNo ratings yet

- 02 - AbapDocument139 pages02 - Abapdina cordovaNo ratings yet

- Environmental Pollution and Need To Preserve EnvironmentDocument3 pagesEnvironmental Pollution and Need To Preserve EnvironmentLakshmi Devar100% (1)

- Getting Started With DAX Formulas in Power BI, Power Pivot, and SSASDocument19 pagesGetting Started With DAX Formulas in Power BI, Power Pivot, and SSASJohn WickNo ratings yet

- Manual Circulação Forçada PT2008Document52 pagesManual Circulação Forçada PT2008Nuno BaltazarNo ratings yet

- March 29, 2013 Strathmore TimesDocument31 pagesMarch 29, 2013 Strathmore TimesStrathmore TimesNo ratings yet

- Caf 8 Aud Spring 2022Document3 pagesCaf 8 Aud Spring 2022Huma BashirNo ratings yet

- Investigations in Environmental Science: A Case-Based Approach To The Study of Environmental Systems (Cases)Document16 pagesInvestigations in Environmental Science: A Case-Based Approach To The Study of Environmental Systems (Cases)geodeNo ratings yet