Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ottoman Heritage in The Balkans

Uploaded by

wez99Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ottoman Heritage in The Balkans

Uploaded by

wez99Copyright:

Available Formats

SDU Faculty of Arts and Sciences Journal of Social Sciences Special Issue on Balkans

Ottoman Heritage in the Balkans: The Ottoman Empire in Serbia, Serbia in the Ottoman Empire

Ema MILJKOVIC* ABSTRACT The Ottoman Empire had brought to the Balkans a new administrative and military order, as well as a new religion, but it had not automatically destroyed all existing social relations and institutions. On the contrary, some of them were integrated in the Ottoman state model. As the result of such synthesis, the new cultural circle was created. That particular cultural circle, present even today in the majority of the societies in the Balkans, has usually been defined as the oriental cultural heritage. An impact made by certain civilization, society and culture is seldom one-way street. Regardless the strength and vitality of certain societies, in conflict or encounter of two civilizations there is usually mutual influence, where not only the society in incline, but also the society in decline has something to offer to the other side, in the measure in which that other side is open to the foreign influences. The aim of this paper is to show the Ottoman influence on the Serbian society in the period from 15th to the beginning of the 19th century, but also to point out certain Serbian influence to the Ottoman administrative and state system. Key words: Ottoman Empire, Serbia, oriental cultural heritage, oriental civilization, social history Introduction The Ottoman military force in the Balkans had gained its full swing during the first years of the second rule of sultan Mehmed the Conqueror (1451-1481). By the fall of Novo Brdo (1455), and then the capital of Smederevo in 1459, the Serbian state had vanished from the historical stage, and its territory had become the integral part of the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans, who had defined their state with two basic attributes: Islamic and military, had brought along the new administrative order, based primarily on the Islamic law, the sharia, along with recognition of the traditions of the previously existed Islamic states (primarily the Abbasside Caliphate). The Ottoman rulers, especially Mehmed the Conqueror (1444-1445; 1451-1481) and Suleyman the Lawgiver (1520-1566), well aware that the administration in the newly conquered territories should be properly defined, but

Prof, Ph.D, Department of History Faculty of Philosophy Ni University Serbia

130

Ottoman Heritage in the Balkans: The Ottoman Empire in Serbia, Serbia in the Ottoman Empire

also aware of the limitations of the sharia law1, had proclaimed the secular regulations, qanuns. The qanuns differed from province to province of the Ottoman Empire, since they acknowledged the local characteristics of the regions. It is important to know that some of the legal regulations of the conquered lands were incorporated in those regulations, as well. The Ottomans had accepted the hanefi madhab, which has a reputation for putting greater emphasis on the role of reason and being more liberal than the other three schools. It entails the use of reason in the examination of Quran and Sunna, so as to extrapolate the judgments necessary for the implementation of Islam in a new environment.2 The Serbs had contributed to the Ottoman history and civilization by offering to it two well- known sultanas (Olivera, wife of Bayazid I and Mara3, wife of Murad II), as well as couple of important public officials. Maybe the most distinguished among them was Sokollu Mehmed-pasha, the grand vizier for fourteen years (1565-1579), under the three rulers and certainly a political person who played one of the most important roles in the Ottoman history of the second half of the 16th century. The political implications of the Ottoman conquest are well known and researched in the historical literature into the details. However, the changes of the social relations structure had been much slower, thus the history of the Serbs under the Ottoman rule in the second half of the 15th century could be considered as the period of continuity rather than discontinuity, in comparison with the first half of that century. In the majority of the qanuns, valid for the Serbian lands in the second half of the 15th century, could be observed the whole range of the legal regulations taken over from the Serbian independent state, as well as the influence of the Serbian medieval law. The good examples for this statement present the legal regulations issued during the second half of the 15th century and the first half of the 16th century, for the sanjaks (provinces) of Srmederevo, Kruevac, Klis, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Examination of the above-mentioned texts reveals couple of dozens of words of Slavic origin, which were used in the Ottoman language, due to the lack of the adequate Ottoman expressions4. In some cases, the scribe thought that the usage of the original

1 The sharia law, whose foundation is in the Quran, was organized as a legal system during the 8th and 9th century A.C., but it could not possibly provide adequate solutions for all situations emerging along with changing of the social relations through centuries and in different historical circumstances. Dursun-beg, the Ottoman writer (end of the 15th century) stated that the sultan had right to proclaim the law regulations on his own initiative. Some other jurisprudents insisted that the qanuns were needed in case when the sharia did not offer the solution for existing problem, but it had to be in accordance with certain accepted customs, so that the analogy could be made (qiys). For more details, see: D. Tanaskovi, Islam dogma i ivot, Beograd 2008, 108-115; H. Inaldik, Osmansko carstvo (Klasino doba 1300-1600), 99-101. 2 For more details, see: D. Tanaskovi, Islam dogma i ivot, 116-117. 3 For more details on Mara, see: M. Popovi, Mara Brankovi, Eine Frau zwishcen dem Christlichen und dem Islamishcen Kulturkreis im 15. Jahrh, Wiesbaden 2010. 4 Those expressions were borrowed from the Serbian medieval legal system, thus the Ottoman authorities decided to keep the original terms. See: D. Bojani, Turski zakoni i zakonski propisi iz XV i XVI veka za

Ema MILJKOVIC

131

term was the best choice and solution. Those expressions were mainly used to describe the pre-ottoman institutions accepted in the Ottoman legal and state system, such as batina, Boi, vojnuk, vlah, gornina, katun, knez, komornica, lukno, poboga, primiur, zaruka.5 The best-known example of the influence of the Serbian medieval law to the Ottoman legal system presents the Mining Law proclaimed by the Despot Stephan Lazarevi in 1412. This particular law was incorporated with almost no modifications in the Ottoman legal system. In the qanunname related to the mines, dated 1536-37, in which the mines Novo Brdo, Janjevo, Kratovo, Trepa, Rudnik, Zaplana, Brvenik and Srebrenica were mentioned, the application of the older legislative was sanctioned. The translation of the older legal regulations had been included into this, newer text. The qanunname itself contained around 50 terms, which were not translated into the Ottoman language, but were used in their original Serbian (Slavic) expression. The majority of those expressions were the terms related directly to the mining production.6 This collection of documents present the codex of over-all mining activities in Serbia and Bosnia, including the mining regulations, expressions of the mining tools and production techniques, as well as the regulation of the mining relations. It surpasses, by its essence, the frame of the sharia law, which provides only the regulations regarding the rights of the mine exploitation, as well as the mining taxation. The sharia law does not contain the provisions regarding the relations between the owner of the mine, its lessee (or tenant) and the miners. Those relations had been regulated in accordance with the general rules of the secular laws. However, it is interesting to mention that certain provisions of the mining qanunname dated the period of Suleyman the Lawgiver were directly opposed to the Islamic religious law. The good example is the provision according to which certain illegal deeds related to the mining production, could be punished by throwing the guilty party into the mining hole, as well as the regulation providing the right of morally disputed persons to testify in the court of law. The sharia law of the hanefi madhab does not accept the testifying in the court of law of drunk persons, gamblers, layers, etc, in general persons whose ethics is not in accordance with the Islamic regulations.7 Therefore, the Ottoman authorities took over completely the previous valid legal regulations regarding the mines, including the one regarding the testifying. Such

smederevsku, kruevaku i vidinsku oblast, Beograd 1974, 4; E. Miljkovi, Posebnosti turskog jezika u prvim popisnim defterima Smederevskog sandaka, Istoci i utoci (Collection of works), Beograd 2009, 133-140. 5 See: Istanbul, Trkiye Cumhuriyeti Babakanlk Devlet Arivleri Genel Mdrl, Osmanl Arivi (= ), Tapu tahrir defteri (= TTD), 16 (1476), 1007 (1516), 978 (1528) ; D. Bojani, Turski zakoni i zakonski propisi iz XV i XVI veka za smederevsku, kruevaku i vidinsku oblast, 14, 15, 23, 27, 36, and further on according to the register. See also: E. Miljkovi, A. Krsti, Tragovi srpskog srednjovekovnog prava u ranim osmanskim kanunima i kanunnamama, Srednjovekovno pravo u ogledalu istorijskih izvora, Beograd 2009, 301-309. 6 M. Begovi, Tragovi naeg srednjovekovnog prava, u turskim pravnim spomenicima, Istorijski asopis 3 (1951-1952), 71-74; Idem, Nai nazivi u turskim rudarskim zakonima iz 15. i 16. veka, Anali Pravnog fakulteta 19/1-2 (1971) 19-25. 7 M. Begovi, Tragovi naeg srednjovekovnog prava, 74.

132

Ottoman Heritage in the Balkans: The Ottoman Empire in Serbia, Serbia in the Ottoman Empire

attitude was in the best state interest, regardless some disaccords within the legal system of the Empire. The taking over of the legal solutions from the Serbian medieval legislative could be observed in some other collections of the Ottoman laws, prescribing the position of the various social groups, their rights, obligations and special fiscal status, if existed. That influence was most obvious in the regulations related to the population with the Wallach status, since the Wallach population was the social group taken from the organization of the Serbian medieval state (the notion Wallach was of the Slavic origin, and it was preserved in the Ottoman language as well). The Wallach population, free peasants and cattle-breeders, presented second basic social group within the Serbian society under the Ottoman authority (the first and the biggest one was the reaya group).8 The Wallach population had important fiscal benefits, since they performed the military service for the Ottoman state. They were also the very important colonizing element, thus significant for the Ottoman administrative system. Their status was regulated by the special law regulations called qanun-i eflak. Some other military and paramilitary orders, such as the martoloses or voynuqs, of the Byzantine or Serbian origin had been incorporated in the Ottoman military system, as well. They had important position within that system, especially in the frontier regions of the Empire. II The most relevant social change occurring during the second half of the 15th century in the regions where the Serbs lived under the Ottoman rule was the disappearance of the highly ranked Serbian noble families and beginning of creation of the new Serbian elite which was not of the noble origin and did not have the land in the full ownership; their new social status was obtained by acceptance of the service in the Ottoman army. The examples of the eminent Serbian medieval noblemen becoming a part of the Ottoman ruling class were isolated cases, thus the phenomenon could not possibly be considered as general. On the other side, throughout the second half of the 15th century, could be observed the process in which prominent Wallach chiefs, knezs and primikurs, started to climb up the social scale. This process would reach its peak during the first half of the 16th century. In the Ottoman legislative, the responsibilities of the knezs and primikurs were not precisely determined before the qanunname issued in 1560. But on the basis of the previous legal regulations, which are also very informative, although not so explicit as the above

8 In the Ottoman sources dated 15th and 16th century, the Wallach population had been treated only as a social group, not the ethnic one. For more details on this issue, see: Istorija naroda Jugoslavije II, Beograd 1960, 80-84 (B. urev); Istorija srpskog naroda III/1, Beograd 1993, 65-81 (R. Samardi); O. Zirojevi, Tursko vojno ureenje u Srbiji 1459-1683, Beograd 1974, 170-176, E. Miljkovi-Bojani, Smederevski sandak 1476-1560, Zemlja. Naselja, Stanovnitvo, Beograd 2004, 229-233.

Ema MILJKOVIC

133

mentioned 1560 qanunname, it could be concluded that the duties and rights of the knezs and primikurs in the sanjak of Smederevo had not changed throughout the second half of the 15th and the first half of the 16th century. It is understandable that they were in accordance to the needs of the Ottoman authorities in this province. The duties of primikurs consisted of: 1) help with the tax collection; 2) guard of the territory under their control; 3) care about population movements and prevention of the unplanned migrations; 4) taking part in the campaigns. In return, they were exempted of the tax on the so-called batina of the primikur. The knezs had the similar duties as the quoted duties of the primikurs, with one additional, which was to guarantee for the primikurs. They served with the help of their sons and brothers, as well as through the tekli (messenger) service, in order to keep the communication with the primikurs. For their service, they were granted the timars or knez batinas, which were also exempted of tax. They were also granted one tenth of the penalty money collected by sanjak-beg. 9 Unfortunately, on the basis of the documents in our disposal at the moment, it is not possible to precisely determine the size of those batinas, but according to some fragments it could be concluded that they were two to three times larger than the batinas of the ordinary people, or the size was the same, but the land was of much higher quality; those rules were probably based on the common, the traditional law. In the case of betrayal of ruler interests, knezs and primikurs were severely punished. One of the most serious offenses for a Wallach chief was to hide a Wallach under his authority. When the betrayal was committed by primikur, he would be immediately discarded to the status of the common member of the Wallach community, and the tax collected from his ratays would immediately became a part of the rulers income. In that case, his service could not be inherited by his son or brother, but a person who was able to find new, previously unregistered inhabitants, without permanent residency; new primikur was granted a certain number of ratays. If the similar offense would be perpetuated by the knez, he would be denied his title, as well as his timar, if he was granted one, and the status of his ratays would have been the same as the above described status of discharged primikur ratays. Such a knez would also be reported to the central authority, who would decide his later destiny.10 Although the Ottoman authorities, in the majority of the cases, did not elect directly the Wallach chiefs, the ascent of certain personalities and their families depended on them exclusively. If the knezs and primikurs were loyal in their service, if they managed to obtain the popular respect toward the rulers policy, they were awarded by introduction into the Ottoman feudal system, as the sipahis the timar holders. Several families, as the Baki family11, for example, distinguished themselves among the other families of the knezs and primikurs in the sanjak of Smederevo.

D. Bojani, Jadar u XV i XVI veku, Jadar u prolosti, Loznica 1985, 84.. Ibid, 85. 11 The historiography had already given large contribution regarding this family. For more details, see: N. Lemaji, Bakii, porodica poslednjeg srpskog despota, Novi Sad 1995.

9 10

134

Ottoman Heritage in the Balkans: The Ottoman Empire in Serbia, Serbia in the Ottoman Empire

The majority of families of the Serbian medieval noblemen escaped to Hungary immediately after or even prior to the Ottoman conquest; those who stayed, either converted to Islam or had been lost in the wider social milieu of the Serbian people. At the end of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th century, the Wallach knezs were the only Serbs who managed to survive as the timar holders. That is how had begun the process of reconstruction of the Serbian society and creation of the new upper class in it, which completely consisted of the members of certain influential Wallach families.12 The reshaping of the Serbian society started again during the 18th century, with emergence of the group of wealthy Serbian merchants, whose culture presented the best example of the above-mentioned synthetic cultural model: amalgam of the elitist Ottoman and traditional Serbian culture. They lived together with the Turks in the ari and traded with them. In order to achieve higher social status, those Serbian merchants started to introduce into their everyday lives models of the ruling, dominant Oriental-Islamic culture. III In certain provisions of the legal regulations regarding the reaya population, and especially in the names of certain taxes, could also be recognized influence of the Serbian medieval legal system. However, those provisions were incorporated in the wider context of the Ottoman definition of the notion of reaya (Ott. , herd) subjects. That concept was based on the basic tax obligation haraj. By paying the haraj tax, the reaya was guaranteed the confessional rights (they could preserve and practice their own religion) and were exempted from the military duty.13 Status of the Christian reaya implied the protection guaranteed by the state, but also expressively subordinated position in comparison to the Muslim population of the Empire. The differences were visible in all aspects of the everyday and social life, and the limitations were stricter in the mixed surroundings. Such position had urged the rural population to lock themselves into their own communities, on one and strengthened the influence of the Oriental-Islamic culture with the urban population, on the other side. The rural settlements, in all provinces of the former Serbian state, which had become part of the Ottoman Empire, had preserved the patriarchal, traditional social relations and culture. The Ottoman authorities did not intervene in the sphere of the internal relations within the rural communities. Their only concern was that loyalty of the subjects and regular collection of the taxes. Thus, the rural societies experienced the period of the ethnographic regression (expression introduced into modern science by

12 13

See also: N. Lemaji, Srpski narodni prvaci, glavari i stareine posle propasti srednjevekovnih drava, Novi Sad 1999. For more detalis, see: H. Inaldik, Od Stefana Duana do Osmanskog carstva, Prilozi za orijentalnu filologiju 3-4 (1953) 23-55.

Ema MILJKOVIC

135

Jovan Cviji), i.e. conservation of the older cultural models, which did not undergo important changes during the period between the 16th and 19th century.14 On the other side, the development of the town of the oriental type had usually began two to three decades after the conquest of the settlement, depending on the achieved security level, as well as on the level of conversion to the Islam. The development of the Ottoman town in the Balkans presented the continuation of the urban development of the existing towns, or formation of the new towns, caused by actual economic, communicational, strategic and other conditions. In the case that kasaba had been built on the base of the medieval Christian smaller towns (Serb. varo), those towns had become the suburban part of the new Oriental town. The Christian mahallas, had gradually diminished by conversion of their population to the Islam. If the existing town had stronger economic base (mine, for example), the process of conversion to the Islam, and along it the creation of the town of the oriental type was much slower. During the entire period of the Ottoman domination in the South-Eastern Europe, such towns had not developed into the important kasabas. However, the new towns established by the Ottomans on the sites of the smaller market places and rural settlements differed by their stronger development and were populated, since the very beginning, by the Muslim population. The introduction of the Ottoman authority had interrupted the further development of the Christian towns. The number of the Muslim population in the urban settlements had increased, during the early decades, by re-settlement of the Turkish population from the eastern parts of Rumelia, where the Ottoman administration and the oriental towns had been established half a century prior to the Serbian lands. The emigrants were primary military, administrative and religious officials, as well as skilled artisans. That process of re-settlement had been terminated during the first part of the 16th century, replaced by the process of the more massive conversion of the local population into the Islam.15 The Serbian population, who lived in the towns, were due, in smaller or larger measure, depending on the epoch, but also from the region (sometimes situation differed from town to town), to obey the sharia limitations toward the dhimmi16 population. Those rules prescribed the payment of the sharia taxes, but also showing of respect toward the Muslim population, including: stepping out of their way on the street; offering hospitality to the Muslim travelers for three days; prohibition of construction of new churches and monasteries, loud religious service and hoisting of the religious insignia; prohibition of

J. Cviji, Antropogeografski problemi Balkanskog poluostrva, Naselja srpskih zemalja I, Srpski etnografski zbornik knj. IV, Beograd 1902, XLV. 15 A. Handi, O gradskom stanovnitvu u Bosni u XVI vijeku, Prilozi za orijentalnu fillogiju 28-29, Sarajevo 1980, 247-257; About the destruction of the Serbian medieval towns, for more details see: D. Kovaevi Koji, La destruction des villes serbes au XVe sicles, Zbornik radova Stadtzerstrung und Wiederaufbau, Zerstrung durch die Stadtherrschaft, innere Unruhen und Kriege, band 2, Bern, Stuttgart, Wien, 2000, 179-189. 16 Dhimmi Term used in the Quran describing the protected population, so called people of the Book (Ar. ahl al-kitab), primarily Christians and Jews.

14

136

Ottoman Heritage in the Balkans: The Ottoman Empire in Serbia, Serbia in the Ottoman Empire

dressing the Muslim way including the prohibition of wearing certain colors allowed only for the Muslims; prohibition for Christians to ride and wear arms; prohibition of sale of non-allowed food and drinks to the Muslim population; prohibition of construction of houses higher than the Muslim ones; prohibition of marriage between non-Muslim male and Muslim female; non-acceptance of testimony against the Muslim in court17 Although all those above-mentioned prohibitions and rules emphasized the concept of the visual domination of the Islam, the common living in the towns led to the more equal way of living between the Christian (in our case Serbian) and Muslim population, which would not be possible if the sharia rules were strictly obeyed. The urban settlements in the Ottoman Empire consisted of the mahallas, which were mostly separated along the confessional lines (thus, a town consisted of the Muslim mahalla(s), Christian mahalla(s) and the Jewish one(s) (in the towns where the Jewish population lived), although there were no strict rule prescribing it. The Ottomans accepted the opinion stated by the Hanefi authority Abu Yusuf that the zimmi population was allowed to live in the all towns of the Empire, even in the Muslim mahallas, to keep their own shops, be the members of the mixed artisan gilds and to practice commerce, on one condition: not to disturb the Muslim way of living. Primarily, it was forbidden to the Christians to open the taverns and to sell the alimentary forbidden to the Muslim population.18 The preserved court records (sijills) testify of the common living in the mahllas on one, and the lively purchase of the estates between the Muslim and non-Muslim population on the other side, which could lead to the conclusion that in the towns the houses of ones and the others could not differ very much. The additional proof to this statement is the fact that the house (konak) of prince Milo Obrenovi situated in Kragujevac (thirties of the 19th century) did not differ from the sarays of the local Balkan pashas; even the haremluk was separated from the rest of the house.19 The similar situation was with the clothing. The explicit and very often proclaimed prohibitions to the non-Muslim population to wear the similar clothes as the Muslim testify that such behavior was very common.20 It has to be kept in mind that the Muslims were the social elite, thus imitation of their clothing style was more expression of the intention to be en vogue, rather than citizen`s disobedience. The same model could be seen in practice of some distinguished Serbs who kept private harems, at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century. Even some of the leaders of the First and Second Serbian Uprisings had several wives or publicly acknowledged mistresses. Among them were Milenko Stojkovi, Jovan Mii, prince

A. Foti, Izmeu zakona i njegove primene, Privatni ivot u srpskim zemljama u osvit modernog doba, Beograd 2005, 37. 18 Ibid, 53. 19 Ibid, 57. 20Ibid, 64-71; M. Koci, Orijentalizacija materijalne kulture na Balkanu. Osmanski period XV-XIX vek, Beograd 2010, 361-385.

17

Ema MILJKOVIC

137

Milo, and some others.21 This shows in which measure the oriental way of living had been accepted by the Serbian bourgeoisie, which had been established as a social group during the 18th century. It seems, however, that the strongest influence of the oriental and Islamic material culture had been achieved in the nourishment culture. With the Ottoman conquest, the nourishment in the Balkans had changed, rapidly and dramatically. It had been enriched by the dishes, which are still part of the menu of the majority of the Balkan nations. It was the nourishment culture that had stepped the boundaries of the fortified lines between the Serbian rural and Oriental urban society and entered, although slower and in lesser degree, the rural surroundings as well.

21

A. Foti, op. cit, 59.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- What Kind of Fool Am IDocument13 pagesWhat Kind of Fool Am IAbel Marcel67% (3)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Big Picture Bible Crafts PDFDocument258 pagesBig Picture Bible Crafts PDFAmy and Caleb Stewart100% (9)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Fallout 1 ManualDocument122 pagesFallout 1 ManualFallout Fans94% (17)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Grade 4 English LanguageDocument4 pagesGrade 4 English LanguageUdpk Fernando0% (1)

- Wounded Knee PowerpointDocument11 pagesWounded Knee Powerpointapi-287412792100% (1)

- Archaeology & Conquest, W. Dever, Anchor Bible DictionaryDocument25 pagesArchaeology & Conquest, W. Dever, Anchor Bible DictionaryDavid Bailey100% (1)

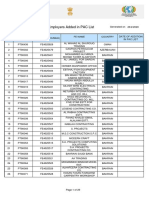

- List of Employers Added in PAC ListDocument29 pagesList of Employers Added in PAC ListCharles DanielNo ratings yet

- HOUSE OF LORDS - The UK and The Future of The Western Balkans PDFDocument117 pagesHOUSE OF LORDS - The UK and The Future of The Western Balkans PDFwez99No ratings yet

- PANORAMADocument7 pagesPANORAMAVũ Quang HưngNo ratings yet

- AELOutline June 2007Document75 pagesAELOutline June 2007mikike13No ratings yet

- Howto TriforceDocument1 pageHowto Triforcewez99No ratings yet

- Altan Vesci LLO Burnton Octovali S Genni Stora Lendi Forma Wosenfeld FardestoDocument1 pageAltan Vesci LLO Burnton Octovali S Genni Stora Lendi Forma Wosenfeld Fardestowez99No ratings yet

- 12 Golden Rules For The Perfect Silicone JointDocument1 page12 Golden Rules For The Perfect Silicone Jointwez99No ratings yet

- GIPE 002309 Contents PDFDocument17 pagesGIPE 002309 Contents PDFwez99No ratings yet

- Zapisnik Aca Stefanovic 2018-01-30Document5 pagesZapisnik Aca Stefanovic 2018-01-30wez99No ratings yet

- 4 Implying Augmented 1 To 4 ChordDocument1 page4 Implying Augmented 1 To 4 Chordwez99No ratings yet

- HeroIdes PDFDocument166 pagesHeroIdes PDFTicciaNo ratings yet

- GIPE 002309 Contents PDFDocument17 pagesGIPE 002309 Contents PDFwez99No ratings yet

- Sidebar FixDocument1 pageSidebar Fixwez99No ratings yet

- Former Yugoslavia - Zhirinovsky VisitDocument2 pagesFormer Yugoslavia - Zhirinovsky Visitwez99No ratings yet

- Migrating Win7Document1 pageMigrating Win7wez99No ratings yet

- How-To Kill A Process On The Windows Command-LineDocument3 pagesHow-To Kill A Process On The Windows Command-Linewez99No ratings yet

- Re FerrersDocument1 pageRe Ferrerswez99No ratings yet

- Shell StylesDocument1 pageShell Styleswez99No ratings yet

- RestrictionDocument2 pagesRestrictionwez99No ratings yet

- Plugin RemovalDocument1 pagePlugin Removalwez99No ratings yet

- GoogleDocument1 pageGooglewez99No ratings yet

- How To Restart Explorer - Exe Process Properly in Windows 7, Vista, XPDocument1 pageHow To Restart Explorer - Exe Process Properly in Windows 7, Vista, XPwez99No ratings yet

- How To Disable The Local Administrator Account On Windows XPDocument1 pageHow To Disable The Local Administrator Account On Windows XPwez99No ratings yet

- Disable Referrers FirefoxDocument1 pageDisable Referrers Firefoxwez99No ratings yet

- Creating Games Explorer ShortcutDocument1 pageCreating Games Explorer Shortcutwez99No ratings yet

- Hidden IexpressDocument2 pagesHidden Iexpresswez99No ratings yet

- Creating Shortcut To Resource Monitor Win7Document1 pageCreating Shortcut To Resource Monitor Win7wez99No ratings yet

- Disable Avira Pop-Ups During UpdatesDocument1 pageDisable Avira Pop-Ups During Updateswez99No ratings yet

- Change YourIP (Through Run)Document1 pageChange YourIP (Through Run)api-3816968No ratings yet

- 3GB SwitchDocument2 pages3GB Switchwez99No ratings yet

- The Mughal EmpireDocument4 pagesThe Mughal Empirerudra rajNo ratings yet

- Teori Florence NightingaleDocument19 pagesTeori Florence NightingaleRahmi ramadhonaNo ratings yet

- MX 2023 Players Cyberface Id List (2k14)Document28 pagesMX 2023 Players Cyberface Id List (2k14)ratou2611No ratings yet

- Sermon 3 - Ban Ieid Ka Long Ban MapDocument4 pagesSermon 3 - Ban Ieid Ka Long Ban MapK. Banteilang NonglangNo ratings yet

- Monitoring DPD & Kol 29062021Document22 pagesMonitoring DPD & Kol 29062021Task ForceNo ratings yet

- Castles of Spain Alcaniz Festiva by Federico Moreno TorrobaDocument5 pagesCastles of Spain Alcaniz Festiva by Federico Moreno TorrobaFelipe Herbert100% (1)

- Daftar Nilai Ganjil Kls 2 2021-2022Document14 pagesDaftar Nilai Ganjil Kls 2 2021-2022fitria nurmala dewiNo ratings yet

- Academic Year Mehmet Akif Ersoy Secondary School 2Nd Term 1St English Written Exam For 6 Grades: - /100Document3 pagesAcademic Year Mehmet Akif Ersoy Secondary School 2Nd Term 1St English Written Exam For 6 Grades: - /100ASEEL ALNAHEELNo ratings yet

- End-Of-term Test 3 (Semester 2)Document10 pagesEnd-Of-term Test 3 (Semester 2)Huyền MaiNo ratings yet

- Yearbook 2016Document164 pagesYearbook 2016manha.ahmaddNo ratings yet

- S5Document14 pagesS5Khaoula DebbabNo ratings yet

- Mcqs On Determiners: A. Both B. Every C. Each D. AnyDocument18 pagesMcqs On Determiners: A. Both B. Every C. Each D. AnyCHHOTOSIJA PRY SCHOOL100% (1)

- Gora by Rabindranath Tagore WikipediaDocument3 pagesGora by Rabindranath Tagore WikipediaLamarNo ratings yet

- Yawshu A Ningbaw Ningla Lai KasiDocument3 pagesYawshu A Ningbaw Ningla Lai KasiLahphai Awng LiNo ratings yet

- The Chart Below Shows The Expenditure of Two Countries On Consumer Goods in 2010Document35 pagesThe Chart Below Shows The Expenditure of Two Countries On Consumer Goods in 2010Vy Lê100% (1)

- 1516673118214895debut ScriptDocument23 pages1516673118214895debut ScriptRoa Recio GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Singapore-malaysia-Indonesia Itinerary (June 4-11,2016) - DraftDocument14 pagesSingapore-malaysia-Indonesia Itinerary (June 4-11,2016) - DraftHij PaceteNo ratings yet

- Ensign Dec 1975 Who and Where Are The LamanitesDocument3 pagesEnsign Dec 1975 Who and Where Are The Lamanitessignal2nosieNo ratings yet

- College of Nursing (Female) Shaheed BenazirabadDocument4 pagesCollege of Nursing (Female) Shaheed BenazirabadUzairNo ratings yet

- Tugas MandarinDocument6 pagesTugas MandarinpujaNo ratings yet

- PublicDocument218 pagesPublicRashmi Kb100% (1)

- Hilmar - Farid-Batjaan Liar in The Dutch East IndiesDocument16 pagesHilmar - Farid-Batjaan Liar in The Dutch East IndiesInstitut Sejarah Sosial Indonesia (ISSI)100% (1)

- Conditional Sentences II, IIIDocument12 pagesConditional Sentences II, IIIsfejziuNo ratings yet