Professional Documents

Culture Documents

KAMINER Abstract PDF

Uploaded by

samilorOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

KAMINER Abstract PDF

Uploaded by

samilorCopyright:

Available Formats

Architectural Autonomy: from Conception to Disillusion

Tahl Kaminer

Abstract

The editorial introduction for this issue of Haecceity Papers describes three categories of contemporary architecture: the technological, the critical and the neo-liberal. All three relate, albeit in very different manners, to architectural autonomy. In the forty years since it moved to the center of architectural discussion, autonomy has become a powerful idea, without which any understanding of recent architecture is rendered partial and limited.

The first of the three categories, technological architecture, is a specific result of the computer revolution in architectural practice, a disciplinary revolution the scale of which architecture has not evidenced since the Renaissance. The central interest of technological architecture has been the study of the new tools available to the discipline, examining the opportunities of designing innovative form and producing exhilarating imagery. The major attribute of this category is newness, which is related to the novelty of both software and hardware. Technological architecture has been driven, primarily, by innovative software of representation rather than as in modernism by technologies of realization and construction. Representation software, unlike construction technologies, is the privilege and professional instrument of the architect. Thus, the work of the protagonists of this category Greg Lynn, Nox, Kas Oosterhuis, Asymptote is an extreme example of autonomous architecture: architecture concerned with the discipline itself, studying its new means of representation.

The relation of architecture to autonomy also stands at the center of the two other categories mentioned by the editorial: the critical and the neo-liberal, the latter of which will be called here the real. Both categories have a longer history than the technological: they rose from the ashes of modernism in the late 1960s, and have dominated architectural discourse ever since, particularly in the United States. Peter Eisenman and K. Michael Hays propagated the idea that autonomous architecture is critical, whereas the category of the real consists of a loosely aligned group of practitioners and critics interested in diverse strategies to engage the everyday reality, whether on a cultural, economic or political level, united in castigating the idea of architectural autonomy. Recently, the antagonism between these two categories has reached a climax with the postcritical debate i .

In the escalating dispute, critical architecture has been commonly conflated with architectural autonomy ii . This correlation, accepted as matter of fact by too many practitioners and theorists, is highly contentious and open to dispute. Understandings of autonomy in art have transformed significantly in the two centuries since it was conceived as a theoretical term; in architecture, autonomy has an even shorter and more ambiguous history. In light of the current debate, the following text will attempt to disentangle the skein of ideas of architectural autonomy and explain their development. To do so, the essay will chronologically progress from the writings of Emil Kaufmann to contemporary understandings of autonomy, concisely relating to a variety of diverse usages of the term in architecture. Autonomy and opposition to autonomy have been central to the disciplines development in the last four decades; the changing status of autonomy itself is, therefore, bound to influence architecture in the near future.

For a concise but potent overview of this debate, see George Baird, Criticality and its Discontents, The Harvard Design Magazine, Fall 2004/Winter 2005, number 21.

See, for example, Bob Somol and Sarah Whiting, Notes Around the Doppler Effect and Other Moods of Modernism, Perspecta 33: The Yale Architectural Journal, 2002, 73.

ii

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Five Easy Pieces Dedicated To Ludovico QuaroniDocument22 pagesFive Easy Pieces Dedicated To Ludovico QuaronisamilorNo ratings yet

- Excellence, de Menselijke Aanwezigheid'Document3 pagesExcellence, de Menselijke Aanwezigheid'samilorNo ratings yet

- ArtCriticism V20 N01 PDFDocument108 pagesArtCriticism V20 N01 PDFsamilorNo ratings yet

- 03 T Avermaete ARCHITECTURE TALKS BACK PDFDocument12 pages03 T Avermaete ARCHITECTURE TALKS BACK PDFsamilorNo ratings yet

- ArtCriticism V07 N02 PDFDocument124 pagesArtCriticism V07 N02 PDFsamilorNo ratings yet

- 05 B Lootsma FROM PLURALISM TO POPULISM PDFDocument16 pages05 B Lootsma FROM PLURALISM TO POPULISM PDFsamilorNo ratings yet

- Conversation With Kenneth Frampton-R.banhamDocument24 pagesConversation With Kenneth Frampton-R.banhamCeyda Genc100% (2)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- How To Present A Paper at An Academic Conference: Steve WallaceDocument122 pagesHow To Present A Paper at An Academic Conference: Steve WallaceJessicaAF2009gmtNo ratings yet

- Power Control 3G CDMADocument18 pagesPower Control 3G CDMAmanproxNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Macroeconomics For Life Smart Choices For All2nd Edition Avi J Cohen DownloadDocument74 pagesTest Bank For Macroeconomics For Life Smart Choices For All2nd Edition Avi J Cohen Downloadmichaelmarshallmiwqxteyjb100% (28)

- ATADU2002 DatasheetDocument3 pagesATADU2002 DatasheethindNo ratings yet

- Rare Malignant Glomus Tumor of The Esophagus With PulmonaryDocument6 pagesRare Malignant Glomus Tumor of The Esophagus With PulmonaryRobrigo RexNo ratings yet

- Adverbs of Manner and DegreeDocument1 pageAdverbs of Manner and Degreeslavica_volkan100% (1)

- Villamaria JR Vs CADocument2 pagesVillamaria JR Vs CAClarissa SawaliNo ratings yet

- Uneb U.C.E Mathematics Paper 1 2018Document4 pagesUneb U.C.E Mathematics Paper 1 2018shafickimera281No ratings yet

- Introduction To M365 PresentationDocument50 pagesIntroduction To M365 Presentationlasidoh0% (1)

- 1 - Laminar and Turbulent Flow - MITWPU - HP - CDK PDFDocument13 pages1 - Laminar and Turbulent Flow - MITWPU - HP - CDK PDFAbhishek ChauhanNo ratings yet

- LS01 ServiceDocument53 pagesLS01 ServicehutandreiNo ratings yet

- Resume NetezaDocument5 pagesResume Netezahi4149No ratings yet

- JP Selecta IncubatorDocument5 pagesJP Selecta IncubatorAhmed AlkabodyNo ratings yet

- Feds Subpoena W-B Area Info: He Imes EaderDocument42 pagesFeds Subpoena W-B Area Info: He Imes EaderThe Times LeaderNo ratings yet

- Chapter Three: Tools For Exploring The World: Physical, Perceptual, and Motor DevelopmentDocument43 pagesChapter Three: Tools For Exploring The World: Physical, Perceptual, and Motor DevelopmentHsieh Yun JuNo ratings yet

- 10 Essential Books For Active TradersDocument6 pages10 Essential Books For Active TradersChrisTheodorou100% (2)

- Tachycardia Algorithm 2021Document1 pageTachycardia Algorithm 2021Ravin DebieNo ratings yet

- Use of Travelling Waves Principle in Protection Systems and Related AutomationsDocument52 pagesUse of Travelling Waves Principle in Protection Systems and Related AutomationsUtopia BogdanNo ratings yet

- 3M 309 MSDSDocument6 pages3M 309 MSDSLe Tan HoaNo ratings yet

- Bài Tập Từ Loại Ta10Document52 pagesBài Tập Từ Loại Ta10Trinh TrầnNo ratings yet

- s15 Miller Chap 8b LectureDocument19 pagess15 Miller Chap 8b LectureKartika FitriNo ratings yet

- PCI Bridge ManualDocument34 pagesPCI Bridge ManualEm MarNo ratings yet

- Lista de Precios Agosto 2022Document9 pagesLista de Precios Agosto 2022RuvigleidysDeLosSantosNo ratings yet

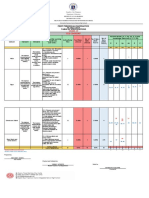

- Revised Final Quarter 1 Tos-Rbt-Sy-2022-2023 Tle-Cookery 10Document6 pagesRevised Final Quarter 1 Tos-Rbt-Sy-2022-2023 Tle-Cookery 10May Ann GuintoNo ratings yet

- Stewart, Mary - The Little BroomstickDocument159 pagesStewart, Mary - The Little BroomstickYunon100% (1)

- Electric Motor Cycle and ScooterDocument9 pagesElectric Motor Cycle and ScooterA A.DevanandhNo ratings yet

- 200150, 200155 & 200157 Accelerometers: DescriptionDocument16 pages200150, 200155 & 200157 Accelerometers: DescriptionJOSE MARIA DANIEL CANALESNo ratings yet

- Manual Ares-G2 2Document78 pagesManual Ares-G2 2CarolDiasNo ratings yet

- NGCP EstimatesDocument19 pagesNGCP EstimatesAggasid ArnelNo ratings yet

- Information Technology Project Management: by Jack T. MarchewkaDocument44 pagesInformation Technology Project Management: by Jack T. Marchewkadeeps0705No ratings yet