Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hindu Temple Fractals - Vastu N Carl Jung

Uploaded by

Disha TOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hindu Temple Fractals - Vastu N Carl Jung

Uploaded by

Disha TCopyright:

Available Formats

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 1 of 31

HINDU TEMPLE FRACTALS

by William J. Jackson, Department of Religious Studies, IUPUI

"As from a blazing fire thousands of sparks fly forth, each one looking self-similar to its source, So from the Eternal comes a great variety of things, and they all return to the Eternal finally." Mundaka Upanishad II.1.1

Opening Question The Idea of Multiple Archetypes Symbolized In Abstract Form Overview of the Complex of Symbolic Meanings Fractal Mountain Universe The Many and the One The Ultimate Purpose Dark Cave as Archetypal Womb and Heart of Light The Hindu Temple Sanctuary as Cave Encountering the Cosmic Person's Identity Interactive Functions of Fractals in the Hindu Temple Complex Around, Inward, Upward at Kandariya Temple

Sketch of a kolam design in rice powder seen on a threshold in Tiruvanamalai, South India, December 1999.

This webpage explores fractal aspects of Hindu temple architecture, examining multiple archetypes and geometry of recursion. It is primarily about architectural design, religious symbolism and imagination. It concerns religious imagination involved in some of the ideas and plans used in Hindu temples. It is not intended to speak to issues of social justice, or economic questions. It is not intended to imply that all temples are the same, or that all temples are perfect institutions. Other studies exist which treat those topics. This short study can offer only a cursory suggestion of the intricasies of the symbol system, the modes of measuring units and proportions, and the reflection of the whole in some of the parts.

OPENING QUESTION

Gazing upon a variety of Hindu temples, one again and again encounters recursive shapes. One sees fractal-like spires (shikharas), and other parts of the architecture

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 2 of 31

which are self-similar to the unity of the whole. Not all Hindu temples are like this but a great many are. Why are these features so common?

Line drawing of the Kandariya temple in Khajuraho.

Drawing from Stella Kramrisch's book, The Hindu Temple

That is, what are these recursive patterns of self-similar forms "saying"? Why is this kind of shape used and not another? What patterns from nature might be involved? What archetypal(1) images, unlabelled metaphors, and worldview meanings, what philosophical and metaphysical concepts are being expressed? What religious experience and spiritual orientation does this form bespeak? How does the geometry express the highest visions of human life and the nature of the human being, the ultimate destiny as understood in the living traditions of Hinduism? How can we read the meanings, analyze the information coded in the mathematics of this "frozen music"? Although we do not wish to imply that Hindu temple design is more monolithic than it actually is, since there are variations both in historical eras and geographical areas, we can generalize about features often or usually found. This study has two objectives-- to elucidate the basic symbolic meanings of Hindu temple architecture and to examine the fractal aspects of temple design. We will confine ourselves to the basics.(2)

Back to Top

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 3 of 31

THE IDEA OF MULTIPLE ARCHETYPES SYMBOLIZED IN ABSTRACT FORMS

It is necessary to consider some basic aspects of the Hindu worldview, overarching and undergirding worldview concepts, to see how they form the background of specific sacred buildings in India. Those who are unfamiliar with Hinduism may not expect a simultaneous complex of ideas expressed in a massive structure. One might expect a single motif in a sacred structure-- a temple in the shape of a chariot, or a church shaped like a ship with an up-pointed prow --and such one-theme structures do exist. But there are also Gothic cathedrals with designs that include a forest of spires, a floorplan which is cross-shaped, a rose window above the main altar and many other forms--statues and symbolic art works-- displaying a combination of themes. The Hindu temple typically involves a multiple set of ideas. Perhaps Hindu traditional architecture has more symbolic meanings than other cultures. It certainly is highly articulated. The temple is oriented to face East, the auspicious direction where the sun rises to dispel darkness. The temple design includes the archetypal image of a Cosmic Person spread out yogi-like, symmetrically filling the gridded space of the floor plan, his navel in the center, and it includes the archetype of the cosmic mountain, between earth and heaven, of fertility, planets, city of the gods, deities, etc.). One encounters these simultaneous archetypal themes and meanings conveyed (and hidden) in the semi-abstract forms in many Hindu temples. There are rules of shape and proportion in the authoritative texts of Hindu tradition (shastras and agamas) which give birth to a variety of complex temple designs. The Brihat Samhita text (4th century CE) says the temple should reflect cormic order. To understand the uses of recursive geometrical forms involving self-similarity on different scales (fractals) in the Hindu temple complex we will need to explore some of these deep images and their uses.

Back to Top

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 4 of 31

OVERVIEW OF THE COMPLEX OF SYMBOLIC MEANINGS

As we have indicated, there are a number of symbolisms combined in the Hindu temple. In fact the Hindu temple is a fusion of archetypes consciously combined and skillfully crafted into structures of abstract geometry and specific numbers. It is a grand synthesis which solves architectural problems using concepts from the characteristically Hindu religious vision of cosmic order. The temple is a visible sign of that mystery, an access point designed to solve life's problems. We will begin with the most apparent -- the rising temple towers with their high peaks. An important Sanskrit word for temple, vimana, literally means "well proportioned, finely organized, a harmonious whole." Prasada is another word for the main body of the temple's superstructure.

Back to Top

FRACTAL MOUNTAIN UNIVERSE

One of the most famous tightrope walkers living today said: "To look up elevates the soul; to watch a falcon take flight from the cornice of a building is to envy its freedom, to consider the world from a loftier perspective. We need altitude as much as we need oxygen. To be surrounded by things of great height -- mountain peaks or skyscrapers -- reminds us of our fragility but also inspires us to reach for the clouds, to take our measure and to stretch it."(3) These observations speak to strong sensibilities in human experience, and usefully broach the topic of the significance of great heights. For countless generations, mountains existing as upthrust geographical areas of higher elevation have nurtured the religious imagination by enticing people with the possibilities of drawing closer to the sky, a realm beyond the human being's usual earthbound reach. Around the world, wherever mountains exist as geographical features of the environment, there are ancient associations -- ideas of reaching up to heaven, contacting a higher spiritual realm.(4) We think of the Himalayas, Olympus, Fuji, Sinai, T'ien-t'ai, and the temple mount in Jerusalem, as well as holy mountains in the Andes, to name but a few.

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 5 of 31

Mountains prefigure the sacred sanctuaries around the world.

Photos by Herb Tobin

In the Hindu experience the idea of the archetypal mountain of existence is mythologized in the cosmic mountain named Meru, the mythological center or navel of the universe. Temple scholar and historian George Michell writes: "In the superstructure of the Hindu temple, perhaps its most characteristic feature, the identification of the temple with the mountain is specific, and the superstructure itself is known as a 'mountain peak' or 'crest' (shikhara). The curved contours of some temple superstructures and their tiered arrangements owe much to a desire to suggest the visual effect of a mountain peak."(5)The fractal structure of some mountains has been researched and discussed by analysts-- self-similar angles of sloping stone are often observable once one has acquired "an eye for fractals."(6) In North India the superstructure is "a solid tower with curvilinear vertical ribs, bulging in the middle and ending in a very narrow necking covered by a distinct ribbed piece of round stone known as amalaka."(7) Temples in South India (an area of about 20% of the subcontinent) typically have a more pyramid-shaped tower, composed of "gradually receding stories divided by horizontal bands, and ending in a dome... or barrel-shaped ridge."(8) South Indian Dravidian culture was already highly evolved before Sanskritic influences arrived from the North-- this accounts for the different styles. In the South tall gateway towers (called gopuras) form entrances to the temple compound; they attained a greater height than the temple superstructure. Here are examples -- one of each kind.

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 6 of 31

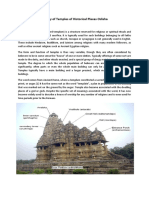

North Indian style temple (left) and South Indian style temple (right).

Left photo by Wes Tedrow, right photo by official temple photographer

While there are a number of variations on the mountain shape in Indian temples, nevertheless "the purpose of the superstructure is always one and the same. It is to lead from a broad base to a single point where all lines converge. In it are gathered the multifarious movements, the figures and symbols which are their carriers, in the successive strata of the ascending pyramidal or curvilinear form of the superstructure. Integrated in its body they partake, each in its proper place, in the ascent which reduces their numbers and leads their diversity to the unity of the point."(9) Thus a structure such as the Kandariya Mahadeva temple in Khajuraho visually conveys a recursive sensibility. It is a whole of self-similar peaks clustered and rising, forming a consistent coherent totality-- the rising slopes of a cosmic mountain. The rising and falling lines lead up to one supreme point of transcendence, symbolic of the ultimate unity which is of supreme importance in many great Hindu traditions. All the features are parts of the ultimate oneness, and so they share the same style, though on various levels and scales of significance and attainment.(10)

Back to Top

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 7 of 31

THE MANY AND THE ONE

This single-pointed wholeness composed of many self-similar peaks at various points in the structure displays a striking fractal quality. Hindus saw fractal-like selfsimilarities in nature, and intuited recursive geometry as a way to express deeply philosophical views.(11) A deep sense of oneness pervades the background of Hindu thought. The One is praised in various ways in the Rig Veda. In Hinduism the One is the ultimate reality with many names and forms (such as Agni, Vishnu, Indra, etc.) "The truth is one though inspired sages speak of it variously," one Rig Veda verse states.(12) In fractal geometry wholeness, whether branching, or clustering or otherwise, contains and is contained in, the parts.

Massive shikhara of the Kandariya temple, showing selfsimilarity of the one and the many in architectural features.

Photo from Stella Kramrisch's book, The Hindu Temple

Back to Top

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 8 of 31

ULTIMATE PURPOSE

"The architecture of the Hindu temple symbolically represents [the quest for moksha-ultimate spiritual liberation, the realization of oneness] by setting out to dissolve the boundaries between man and the divine. For this purpose certain notions are associated with the very forms and materials of the building. Paramount is the identification of the divinity with the fabric of the temple, or, from another point of view, the identification of the form of the universe [for example the cosmic mountain] with that of the temple. Such an identification is achieved through the form and meaning of those architectural elements that are considered fundamental to the temple" which we have mentioned, including mountain, cave, cosmic axis, Cosmic Person or Purusha.(13) In Hindu temples, the highest point of the superstructure is always located directly above the inner sanctum altar,(14) which involves another symbolism, as we shall see. Sensibilities of the sacred which involve concepts of upwardness and inwardness are thus architecturally linked in Hindu design. The Hindu temple is not "a machine to live in" (as French architect le Corbusier defined a modern house), but a microcosm in which pilgrims seek to experience the infinite. It is a structure to reintegrate the part with the whole; it's dynamics involve envisioning and symbolically interacting with features that offer access to experiences of heightening and deepening a sense of the sacred goal and the pilgrim's oneness with it. It is a "tirtha made by art"(15) -- a sacred monument that exists to help the pilgrim cross over to the other shore.

Back to Top

DARK CAVE AS ARCHETYPAL WOMB AND HEART OF LIGHT

There are often caves in mountains, used from ancient times as places of shelter, and also as quiet places to seek contemplative experiences of withdrawal from the world. Caves are known around the world as places for inward reflection, recollection and ritual. Throughout history hermits, sages, monks and yogis have lived in caves in India, China and elsewhere. In legends from Judaism, Abraham while a child hid in a cave for three years. In a central episode from the stories of Christianity, the crucified Jesus was resurrected from a cavern and ascended to heaven on the Mount of Transfiguration. In the Greek

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 9 of 31

mystery religions initiates experienced a spiritual rebirth in underground caverns at Eleusis. In Islam, Muhammad received his revelation in a cave. From ancient times Hindu sages meditated in Himalayan caves. (The Sanskrit term is guha.) Upanishads (Hindu spiritual texts) refer to caves as shelters where yogis practice,(16) and also use cave imagery in depicting the presence of the sacred in the human heart. The sacred is "the primeval one who is hard to perceive, wrapped in mystery, hidden in the cave, residing within the impenetrable depth."(17) Normally our attention is drawn to the world around us, but "entering the cave of the heart, one sees the one who was born prior to heat and waters, the one who has seen through living beings."(18) The nature of this consciousness is described in the Upanishads as Being, Awareness and Bliss -- sat-chit-ananda. Though beyond description, people describe it as "large, heavenly, of inconceivable form; yet it appears more minute than the minute. It is farther than the fathest, yet it is near at hand; it is right here within those who see, hidden within the cave of their heart."(19) In the Upanishadic view the All -- the One-- is found in the secret recess, in the cave in the heart. There one finds the inner core of sacred being, the Atman (Spiritual Self) which is one with Brahman (infinite formless consciousness). To experience this inner light and be established in it is the goal, moksha.

Back to Top

THE HINDU TEMPLE SANCTUARY AS CAVE

George Michell explains the importance of the cave in Hindu practices and in temple design: "The cave is a most enduring image in Hinduism, functioning both as a place of retreat and as the occasional habitation of the gods. Caves must always have been felt to be places of great sanctity and they were sometimes enlarged to provide a place of worship... In all Hindu temples the sanctuary is strongly reminiscent of a cave; it is invariably small and dark and no natural light is permitted to enter, and the surface of the walls are unadorned and massive. Penetration towards the image... is always through a progression from light into darkness, from open and large spaces to a confined and small space. [There are fewer and fewer images, such as sculptures, paintings or decorations, as one goes further toward the sanctuary.] This movement from complexity of visual experience to that of simplicity may be interpreted by the devotee as a progression of increasing sanctity culminating in the focal point of the temple, the cave or 'womb.'"(20) As a contemporary teacher of Hindu spirituality once put it, "The inner you go the more it's pure and simple." Cool, quiet, with less sensory stimulation, the sanctuary is an "objective correlative," to use T.S. Eliot's phrase, of serene deeper consciousness discussed in Hindu philosophy.

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 10 of 31

Image of Hanuman in a shrine in Banaras, with cavelike darkness in the recess.

Photo by Wes Tedrow

The simplicity of the inner recesses keeps the subjective experience focussed, in the intimacy of silence, to face the mystery of the sacred. Psychologically this deepening of awareness and awe corresponds to the elevation of the shikhara above: "Accompanying this penetration inwards toward the cave is the ascent upwards to the symbolic mountain peak, whose summit is positioned over the center of the cavesanctuary. This means that the highest point of the elevation of the temple is aligned with the most sacred part of the temple, the center of the inner sanctuary which houses the image of the god. Summit and sacred center are linked together along an axis which is a powerful projection upwards of the forces of energy which radiate from the center of the sanctuary."(21) Penetration to the inner unknown is thus at the same time symbolic of an ascent to enlightenment-- the temple is meant to express and facilitate this experience. Corridor in the Ramanatha Swamy temple, Rameshwaram, Tamil Nadu, South India. The pillars give

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 11 of 31

a sensation of recursion suggesting infinite depth.

Photo by official temple photographer

Approach to the garbhagriha, the cave-like cube-shaped "womb room," often involves recursive architecture. The pilgrim passing evenly spaced columns experiences a rhythmic sensation. "The architectural rhythms of the Hindu temple impart to each building its consistency and wholeness. They evoke in the devotee an adjustment of his person to its structure; his subtle body (sukshma, sharira) responds to the proportions of the temple by an inner rhythmical movement. By this 'aesthetic' emotion the devotee is one with the temple; and qualified to realize the presence of God."(22) In the rhythms there is a kind of visual music. To amend Paul Claudel's famous verse, music is the soul of [temple] geometry. The name garbhagriha refers to the pilgrim finding his way to this secret inner place and being reborn from it, emerging later, transformed, into the light.

Emerging into the light from a South Indian temple.

Photo by Marcia Plant Jackson

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 12 of 31

Unseen, invisible, but used as the conceptual pattern drawn on the floor plan, the archetype of the Purusha or Cosmic Person, is another feature fundamental to the design of the Hindu temple.

Back to Top

ENCOUNTERING THE COSMIC PERSON'S IDENTITY

We have not yet considered the underlying floor plan-- the layout of the base of the Hindu temple put in place before the massive edifice is mounted up. Before considering that geometric plan, it is necessary to recognize certain ideas in the Hindu outlook. Hindu culture is less enamored of sheer nature than classical Taoism in China. The word "Sanskrit" suggests high culture, the refined-- not raw and spontaneous but well-shaped, "confected," not amateur but classical. The idea of a cave is important, but nature's rough cave, a mere hole in the rock, is refined in the temple into a smoothened archetype, a well-made shape, deliberately rectangularized in form to express an idea. Similarly raw impulses and passions are to be controlled and sublimated in yoga. All of this concern to shape raw nature into refinement has geometric implications for temple design. Since the circle is found in nature it is considered too natural to be favored in Hindu sacred architecture, which seeks to participate in the divine realm. The square is a consciously artificed shape. The Hindu temple is based on the square because it is conceptualized as a perfect form. "The circle and curve belong to life in its growth and movement. The square is the mark of order, of finality to the expanding life, its form; and of perfection beyond life and death."(23) This idea of the circle being less refined and less perfect than the square may sound odd to moderns, including contemporary Hindus. Ancient symbolism goes back to the original thunderbolt emblem put on Indra's banner by the divine artificer Vishvakarma, and the shapeof the Vedic altar and fire container, and the shape of Mount Meru with the four directions of the four castes at its base, and other ancient ideas. The proportions derived from the human body with arms outstretched to the sides also form a square. The square is conceptualized as the perfection of the order of creation which encompasses the circles of time. The circle involves motion, while the square stands for the balance of dualities. Thus, because of these ancient associations, the squate is the prominent symbolic shape in architectural forms, as Stella Kramrisch and others have pointed out. That said, we can explore the meaning of the typical floor plan, the vastupurusha grid

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 13 of 31

of 64 or 81 squares, and the cosmic person's outline within the over-all square shape. Image of the Cosmic Person drawn in an old manual used by temple architects.

Drawing from George Michell's book, The Hindu Temple

The Cosmic Person is sung in Rig Veda hymn X.90, which tells the origin story of self-sacrifice. In it the divine original person of vast dimensions divided to become the various parts of creation. This paradigmatic primal event is recalled and repeated ritually by traditional Hindus whenever they undertake significant actions-- such as planning a city or a temple. To clear and level land at a sacred site, to ritually purify it, to measure and lay down the foundation lines, orienting the structure to the East, involves conceptualizing the construction as a replication on a different scale than the original sacrificial scenario. And like the Vedic altar, the construction ritually enacts the restoration of the Purusha's body.(24) To use a musical metaphor the vastupurusha mandala is the tonic, the stable tone humming in the background over which the superstructure melody of forms takes shape. It is a diagram, or yantra, a geometrical device to represent an aspect of the supreme and make it available to the pilgrim. "The form of the temple, all that it is and signifies, stands upon the diagram of the vastupurusha. It is a 'forecast' of the temple and is drawn on the levelled ground; it is the fundament from which the building arises. Whatever its actual surroundings... the place where the temple is built is occupied by the vastupurusha in his diagram, the Vastupurusha mandala.... It is the place for the meeting and marriage of heaven and earth, where the whole world is present in terms of measure, and is accessible to man."(25) The cosmic person became the universe, and to recreate this origin is to construct a cosmos which offers a return to the transcendent oneness. The vastupurusha mandala is a microcosm with some fractal qualities. As shown in the illustration, there are self-similar squares within squares within squares. The

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 14 of 31

geometric configuration "of central squares with others surrounding it is taken to be a microscopic image of the universe with its concentrically organized structure." Thus the grid at the spatial base and temporal beginning of the temple represents the universe, with its heavenly bodies. It is also more-- it simultaneously symbolizes the pantheon of Vedic gods-- "each square [is] a seat of particular deity."(26) The gods altogether make up the composite body of the Purusha.

Two Vastupurusha mandala plans from architectural texts.

Drawings from George Michell's book The Hindu Temple

The Purusha is the Universal Essence, the Principle behind all things that exist, the Prime Person who is a spirit, the origin of all. "Vastu is the site; in it Vastu, bodily existence, abides and from it Vastu derives its name. In bodily existence, Purusha, the Essence, becomes the Form." The temple building rising above the diagram is a massively substantial structure. "The 'plan' mandala is the ritual, diagrammatic [subtle] form of Purusha. Purusha himself has no substance. He gives it his impress."(27) The navel (or in some texts, the heart) of the outlined Purusha is in the center of the central square of the grid. "In the Purusha, Supernal man, the Supreme Principle is beheld. Man and Universe are equivalent in this their indwelling center...."(28) There is divine city imagery also involved in the grid.(29) There are 32 types of mandalas, an array of configurations of squares in arithmetic progression, beyond the scope of this piece. Around the border of the vastumandala there are 32 squares, each with a presiding deity, to stand for the cardinal and intermediate directions. This border represents the passage of the moon in its complete cycle.

Back to Top

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 15 of 31

INTERACTIVE FUNCTIONS OF FRACTALS IN THE HINDU TEMPLE COMPLEX

There are many different sizes of temples in India, from small village temples to vast urban temple compounds. Traditionally the temple has been the most prominent religious institution in India. Each one in its own way is a center of educational, cultural, social and economic activities. Ritual worship (usually not done congregationally but performed for small groups of pilgrims throughout the day) at sunrise, noon, sunset and midnight, as well as other times, activates the divine presence, with offerings of light, fragrance, music, food, flowers and chanting. The temple is the place for solemn vows, initiations, legal oaths; it is a refuge in times of soul-searching and solace seeking, a place for thanksgiving when prayers are answered, a place of well-being and prosperity, order and meaning. The Hindu temple is an attractor with a variety of visual aspects, and wherever one engages one of them, entering a doorway, circumambulating (ritually walking clockwise around the whole edifice while intently gazing upon parts of it), or approaching the inner sanctuary, or worshipping there-- one is accessing an aspect of the whole. The dynamic is like that of a complex system with multiple feedback flows each giving access into the whole system of metaphysical vision. The temple offers means of engagement in the nuances of the mystery, depending on the stage of development of the pilgrim; a child arriving for the first time experiences certain aspects according to her capabilities, while an elder returning after many previous visits experiences others. The spaces of the HIndu temple involve a dynamic system of traffic flows and feedback loops organized to give a variety of ritual activities, involving the worshippers' mental and physical interactions. "A Hindu temple is a synthesis of many symbols. By their superposition, repetition, proliferation and amalgamation, its total meaning is formed ever anew."(31) This capacity for ever-changing recursive experiences is a vital aspect of Hindu temples, and is often ignored by observers because it is easier to think of the temple as a static structure. The many pilgrims arrive from different backgrounds and locations, each experiencing different aspects of the whole-- yet each aspect can reflect to some extent the whole, or lead further into it. There is a constant renewal over the generations, through the repetition of basic Hindu rituals, the rededication to ideals, and the perpetuation of the philosophical views-- thus the temple serves to inspire. It enacts the mystery that seems to be at the heart of India-- the simultaneous co-existence of the One and the many, the many and the One. It works to help the many pilgrims envision the One in the many, the One found in each one.

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 16 of 31

A temple in Banaras with selfsimilar spires composed of smaller and smaller spires, suggesting the idea of underlying unity.

Photo by Wes Tedrow

Among the examples of ways temple features function to Involve pilgrims are what I would call "Fractals of Circumambulation." By that I mean the recursive action of walking repeatedly around the structure intently looking at its features and thinking of its meanings. "In the rite of circumambulation [the pilgrim] draws and becomes the outermost perimeter of the building; he 'com-prehends' it while walking round it, sees the images not from one side but covers them by his look, one at a time, during his approach and onward progress; while he identifies images thereby evoking its name, the total power of the place which the image occupies is sent as it were into his presence from the centre of his devotion."(32) This recursive action of circling the structure, and also circling the sanctum sanctorum within it, involve wholeness approached through the parts, interiorizing and reflecting on the meaning according to individual attainment. It is a communion incorporating the sacred through mental intention while returning around and around. (Similarly in puja the worshipper moves a flaming lamp of camphor around and around the sacred image while bells are rung and songs are sung.) A description of some of the details can help us understand the practice of circumambulation further. The main body of the temple often gives an impression of fullness; swarming with figures it suggests infinity of being. "The sculptures on the outside of the Prasada are stationed around its body, and while they give an exposition of its meaning they are also its ornaments. By their sequence they form belts around the body (akriti) of the entire temple and its several projections. The latter often form part volumes of their own, massive monumental supports of miniature replicas of the whole temple, each with its own superstructure (shikhara,

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 17 of 31

sringa) thus the ultimate meaning of the temple is brought near to the devotee; at every turn he sees the figures on the walls forming the basis of an ascent towards one high and central shape."(33) At every step, from every angle one sees fractal glimpses of the whole, partial perspectives on the total and ultimate-- this architectural arrangement helps the pilgrim keep the purpose of the visit in view. The images in a temple are re-produced on different scales. Large scale images remain in the sanctum, and smaller scale images are taken out for procession during festivals. Reproductions can be taken home by pilgrims. In the temple "tanks" outside temples in South India there are often pavilions resembling the temple rising up out of the pools of water.

A South Indian temple bathing pool with templelike pavilions.

Photo by Marcia Plant Jackson

At festivals there are similarly shaped tall chariots wheeled through streets, like mobile offspring of the temple.

A chariot festival in Kadugodi village, Karnataka, South

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 18 of 31

India. The chariot being pulled is shaped like a South Indian temple

Photo by Marcia Jackson

Thus, reflection on the fractal qualities of the architecture makes Hinduism's grasp of the whole, and Hinduism's ultimate vision, more comprehensible. "Such an understanding of monumental form by the ritual encompassing movement is a realization as much by the eye as within one's whole living person in motion."(34) Thus, there is made available a holistic progression toward the goal of Hinduism-oneness-- involving the whole person, eyes envisioning, mind devotedly intent, legs taking steps, hands in prayers, and so on. Also, the repeated motifs carry associations with the cyclical time scheme of Hindu worldviews. "This overlapping of cycles of time and repetition of cosmic eras finds visual expression in the forms of the temple, where architectural and sculptural motifs repeatedly appear in different sizes in different parts of the building."(35) This resonance of self-similar geometry and multiple cycles of time is another reason for recursion in Hindu designs. Hindu intuitions that the timebound cosmos is cyclical-on vast scales the four cosmic ages wheel round and round, and on a smaller scale individuals are born again and again, as well. There are seasons, cycles of the moon, cycles of day and night, cycles of breath... Furthemore, in the lives of Hindus there are ritual counterparts to the kind of recursion which recapitulates the main shape of the prasada again and again,

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 19 of 31

reflecting the whole pattern. For example, phases in an individual's life cycle are marked by major turning points, rites of passage, such as the baby's naming ceremony, the initiatory thread ceremony, the wedding ceremony, and the retirement ceremony. As part of the wedding ceremony there is the recapitulation of the earlier rites. I was told by Hindus that the ceremonies are re-iterated, with Sanskrit prayers being said again by the officiating priest, in case they were previously omitted or done improperly, to provide a sense of completeness, and for general religious merit. At the rituals for reaching the ages of sixty and eighty the previous rites are repeated, including the wedding. The hymn of the Cosmic Person (Rig Veda X.90) is used in the sixteen main samskaras, as the sacrificial origin of creation is repeated in all significant acts. This capacity for re-iterative experience is vital to Hindu treaditions. Perhaps it is the Hindu way of accomodating human nature's recurrect need for a sense of completeness at various points in the It is difficult to imagine fully how repetition make the structures of Hinduism not static but dynamic unless one is present to observe the practices. In a sense the temple is rather like a fractal expression of the whole ethos of Hinduism. There are other nuances of religious intentions too, in the deliberate fractal-like designs and other forms of mathematical recursiveness in Hindu temples. The systems dictated by the orthodox lawbooks are the means used to control the proportions of the dimensions of the temple. An important feature of these systems is the standard unit of measurement, often known as a "finger" or angula, "from which are derived the dimensions of the sanctuary or the height of the image of the deity housed there." The number of these "fingers" is what "regulates the masses of the temple as they extend upwards and outwards from the sanctuary. Every part of the temple, therefore, is rigorously controlled by a proportional system of measurement and interrelated by the use of the fundamental unity." The measurements are deliberately not exactly symmetrical.(36) This proportional harmonization of design is of utmost importance in the construction of a temple because the power of the place is thought to depend upon correct measurement. Faith in orthodoxy spelled out in the traditional texts and the orthopraxy of the interpreters and master craftsmen involves a deep belief. "Only if the temple is constructed correctly according to a mathematical system can it be expected to function in harmony with the mathematical basis of the universe. The inverse of this belief is also held: an architectural text, the Mayamata, adds that if the measurement of the temple is in every way perfect, there will be perfection in the universe as well."(37) Thus, the well made temple radiates well being; the welfare of the world surrounding the sacred location depends on the temple's well organized exactness for auspicious energy. Thus, human beings play a part in maintaining the cosmic order. Exact arrangements of numbers are crucial in Hindu temple design. The square of 4 - 16 -- is considered a perfect number, and it that square of squares is marked out in the Vastupurusha mandala, but the square of 8 units is also significant.(38) "All the main horizontal as well as vertical proportions are referred to the Mulasutra, the basic

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 20 of 31

width... This is differently expressed; the area of the Prasada is to be divided into 16 (First Norm) or 64 (Fifth Norm) squares; its width is 4 or 8 units respectively and refers in either case to the Vastumandala called Manduka. All the proportions here form octaves; the width of the Garbhagriha being 2, that of the Prasada is 4, this is also its height; it is a perfect cub and from it rises the Shikhara to twice this height; the wall measuring 4, the Shikhara has 8 units in height. The geometrical progression: width of Prasada or height of wall; and height of shikhara links the temple in its horizontal and vertical extent and interrelates their main parts. Analogous is the proportion between the thickness of the wall, its internal and external width. The ratio 2:1 or the Octave is the leading theme of the First Norm as given in the Vishvakarma prakasha text; with it is interwoven the Fifth Norm, as the total height of this kind of temple is three times the width of the Prasada, the height of the Shikhara being 2/3 of it."(39) The square is said to be the measure of man, because a person with arms extended to the sides reaches out as wide as his body is tall. Thus a sacred mathematics is of great importance in this practical art, a math "composed of a language of precise measurements, which permits a symbolic realization of the underlying cosmic ideas."(40) It is said in a treatise that by itself knowledge of the traditional science and the meanings entailed in it and mastery of the craft do not make a perfect architect. That complete mastery also requires immediate intuition, a readiness of judgement or wise decision in the midst of life's contingencies. Complete mastery also requires the talent of fusing the the requirements, meanings and unique opportunities into the requirements of the whole. (41) Thus, following the rules faithfully and improvising wisely are both necessary for the true architect, who adapts the timeless ideal to the materials, needs of the situation in his specific time and place.(42) There is thus great variety as well as underlying unity in Hindu temples.

Back to Top

AROUND, INWARD, UPWARD at KANDARIYA TEMPLE

To reiterate and carry further the points made thus far, let us imagine a visit to Kandariya Mahadeva Temple, Khajuraho, Central India. On the horizon as you approach the 11th century temple dedicated to Mahadeva Kandariya ("Shiva as Lord of the Cave"), you notice the rising spires of the temple silhouette are very much like mountain peaks. But it is an idealized mountain, with pleasing ornamental symmetries, using a more regular geometry than the crags of

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 21 of 31

most mountains. Light from the sky seems to be playing in the spaces between the peaks, like streams of life-waters flowing from the heights, down through the space of empty valleys from the Himalayan heights. You remove your sandals and wash your dusty feet in the cool water of the temple tank to the left of the temple, when you arrive. Built up on a stone platform, the temple has an entrance above the ground level, thus you must climb a long flight of stairs to approach the structure, and this gives you a feeling of exerting yourself to rise up higher and higher. The temple is considered a spiritual axis where earth and heaven meet, so the pilgrim's progress here is associated with arriving Kailasa, the heavenly realm of Shiva. The Kandariya temple contours in silhouette make a fractal impression. Some parts are even reminiscent of features in the Mandelbrot set. The supreme shikhara or spire of utmost aspiration is made up of smaller scale selfsimilar subsidiary shikharas, rising from yet smaller ones. The eye is drawn up higher to the utmost peak, the main point of the whole which is reflected in the parts. This is a vision of the cosmic mountain, center of the world. The ideal form so gracefully artificed suggests the infinite rising levels of existence and consciousness, expanding sizes rising toward transcendence above, and and at the same time housing the sacred deep within. The gated enclosures-within-enclosures enshrine the inner sanctum, which for Hindus holds an external likeness of the inmost depths of divine mystery. The rising, fractal-like shikharas of Kandariya temple in Khajuraho. Photo from Stella Kramrisch's book, The Hindu . Temple Gazing at the shikharas we are struck by the beauty. The mountain peaks are geometrically finessed, ornate, describing a fancy edge between our time and space and the perfection of eternity and infinity. Perhaps, it is as if ordinary people are privileged to see the glorious mountain reflected in the consciousness of the illumined sage. The temple, like all Hindu cosmic images, is a microcosmic reflection of the

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 22 of 31

play and patterns of consciousness in the pool of time, a context in which pilgrims can locate themselves and make their way further on the inner journey to inmost depths, to approach closer and glimpse spiritual truth, the beyond which abides within. As we circumambulate the mountain tilt back your head and see how the mountains are full of figures-- populated by sculptures of Shiva, the Goddess, saints, musicians, dancers. There are also images of loving couples exhibiting the erotic powers of life. (43) The Hindu temple is a geometric structure meant to bring the divine within reach, and to take man to the heights beyond. Thus, it is a carved stone embodiment of archetypal life's fecund profusion and phototropic thrust, guarded by phantasmagoric images of power. It is a place which celebrates and seeks to propel spiritual evolution. At the door we remember that the rite of Garbhadhana was performed before this temple was built. A small silver or gold casket with dimensions proportionate to the completed temple, its base divided into compartments like the Vastumandala, containing auspicious and representative items such as gems, metals, soils, herbs, and a symbol of the presiding deity, with an image of the serpent of infinity ("Ananta") on the floor, and on the lid a mandala of the earth with its seven continents, oceans and mountains was buried amid chanting in the temple wall to the right of the door, above the level of the first row of stones.(44) So once again within the overall structure, a miniature temple with symbols of its powers stands embedded in the temple, hidden like a fractal seed of the temple's life and character. And in the central compartment is a symbolic seed with meanings related to the underlying power of origin of the casket.(45) There are recursive ritual actions involved in the "seed rites" which are performed before the building the temple, before the last stone is placed in the superstructure, before the main image is installed, and before the consecration of sacred vessels.(46) Entering the mountainous temple from the East, one steps through a series of ever more sacred enclosures, moving deeper into the most sacred area. One is attracted toward the centermost inner sanctum which is thought to radiate subtle energy in four directions. One arrives at the cave-like holy of holies. The Lingam/yoni at the heart is seen here in the shadows, where flowers are offered, and cool libations, and the white light of burning camphor. The Lingam/yoni at the heart of the temple is also considered to co-incide with the antarjyoti or inner light at the heart of worshippers, the divine mystery of timeless transcendent power poking through into this world of time. This is the core of the Kandariya temple-- a symbol of a vision of wholeness-Shiva and Shakti in union, Spirit and Body, God and Creation together as the One, ultimate reality. The aniconic image radiates power upwards to the heavens, and also resonates in the pilgrim's inner reality with the idea of knowing one's Self (Atman), conceived in Hinduism as eternal consciousness. (This is like the Christian teaching that "The kingdom of heaven is in the heart"). One circles the sanctum, circling the universe, thereby symbolically circling the divine, touched and hushed by the sacred space. Through these recursive acts the Hindu hopes to make contact with the

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 23 of 31

sacred and to remain in contact with the higher Self, even after leaving the sacred precincts.

Color image of the Kandariya temple, Kajuraho.

Photo courtesy of official temple photographer

Circling the light, going around the image in the inner sanctum, and being circled by the light, symbolically being born from the "womb room" into the light, going from the mountain to the light beyond-- worshippers involve themselves in these processes. Pilgrims enact the process, recognizing the order, ritually progressing from this world of time, from samsara to moksha, eternal light. The theme of seeking the light, finding and being inspired by the light, is very ancient in Hindu traditions. It is expressed in the universal prayer which summarizes the Vedas: "Om, in these three realms, earth, atmosphere, and beyond, we meditate on the glorious light which causes the sun to shine, may that light impel our thinking, flow in our thought-stream." it is expressed at the thread ceremony which initiates Hindu youths into full-fledged membership in the adult community, when a circle of string through which the initiate's head and shoulder emerge, symbolizing the sun-door or thye portal to the beyond. Thus initiation symbolizes a partial advance to that spiritual; light. It is expressed in the image of stolen cows of light hidden in a mountain cave described in Vedic verses. These cows are liberated by Indra to come out like the light-filled clouds of dawn. It is expressed in the temple puja of waving lights and practices through which the piulgrim enters the light and emerges again with the light of transcendence. The aspirations of the Vedas, which at first and for a long time, had no permanent structures to represent them, eventually were articulated in wood and then stone. The Vedic prototype rises up from images in Vedic chants and horizontal designs of fire altars into vertical visibility. As Stella Kramrisch puts it: "A living memory builds the buttresses of the Hindu temple in a pattern similar to that in which the bricks were laid in the Vedic Altar... With the prototype of the Vastumandala as the tonic, the ground plan is laid out rhythmically 1.)from the centre, 2.)along its perimeter and 3.)once more from there in rhythms in which is summed up the inner impact of movement; it acquires visibility on the outside of the building which is clasped by its indentations and arises in the gradations of its planes... The architectural rhythms of the Hindu temple impart to each building its consistency and wholeness. They evoke in the

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 24 of 31

devotee (bhakta) and adjustment of his person to its structure; his subtle body (sukshma sharira) responds to the proportions of the temple by an inner rhythmical movement. By this 'aesthetic' emotion the devotee is one with the temple; and qualified to realize the presence of God."(47) The temple offers an aesthetically designed location for experiences, ways to act and to be acted upon. It shows the pilgrim the mountain of his or her aspiration. It gives pilgrims an approach to the cave of inward penetration. It returns Hindus to the ground of the cosmic person whose reconstitution is the finding of original unity, the light beyond and within. It gives one the experience of darshan, to see oneself being blessed by the glance of light upon one, and to witness the brilliant light of burning camphor. It gives the pilgrim a momet to ech with the priest's prayer, and to smell such auspicious fragrances as incense and ghee, camphor and honey, flowers and coconuts. (At Tirupati there may also be the aroma of laddus -- gram, ginger and jagary.) The temple's purpose is to awaken a timeless person to go forth again into creation, refreshed by experiencing anew the human/cosmic situation in structures of sacred geometry, including many recursive patterns. The archetypal symbols fused in the temple architecture work on the Hindi pilgrim both cosciously and unconsciously. with multiple possibiities for dramatic and subtle encounters concentrated in one fractal-like integrative sacred space.(48)

Ideally, in the Hindu temple the sacred descends to earth and humans ascend to the spirtual realm. Collage by William J. Jackson

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 25 of 31

Designers must make a very large number of decisions when a public monumental structure is erected. The natural source and inspiration for these decisions can be found in the traditional worldview, the time-honored values of the society. That legacy is expressed and celebrated in the work. Architecture needs to be configured in the context of the dynamics of the cosmos, oriented to the directions, adjusted to the planets, symbolically showing attunement to a higher order. The temple provides a place where the self can seek fulfilment in larger contexts. The temple, with its interactive circuit in space and its symbol system of participation leads the pilgrim further into the unknown aspects of being. In the temple's precincts one is encouraged to let go of the supremacy of the calculative mind and the overly purposive narrow waking consciousness. In reaching the center of sacredness one admits one's limits, submits to mystery and providence beyond one's control. There one can hope to be attuned to the larger reality. Worship opens one to reverent surrender. As Christians say, "Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven." Like other complex practices in India the temple structure is a kind of language which

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 26 of 31

makes more and more sense when one learns the vocabulary or symbol system of ideas involved. Much is encoded in the mathematics of structure, the life in the stone, infinity in the finite, the beyond in the within. In a sense, the temple is a fractal part of the whole of Hinduism, reflecting in architectural shapes and scales self-similar aspects of the total pattern and the ultimate vision. The whole is reflected and celebrated in the parts.

This collage of upward-gazing faces shaped like a mountain is based on a face drawn by A.K. Coomaraswamy.

Collage by William J. Jackson

Back to Top

NOTES

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 27 of 31

1. An archetype is a symbol so deep and pervasive in many peoples experiences, worldviews and stories, that it is for all intents and purposes universal-- such as the chaotic primordial waters in so many stories of origin, and the mountain or mound of form rising from formless waters. These images appear in a great variety of forms in different cultures, with different names and nuances. See the work of Carl Jung for more on the meaning of archetype. Carl. G. Jung, Psychological Reflections, Jolande Jacobi, ed. New York: Harper and Row, 1961, pp. 36-45. Hillman emphasizes the dynamic valuing quality of the term archetypal. James Hillman, A Blue Fire, New York: HarperPerennial, 1991, p. 26. 2.Readers seeking more details and depth are directed to Stella Kramrischs two volume study The Hindu Temple, New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1980. For another website on Hindu temple designs see "Vastu Shastra and Sacred Architecture," by Swami B.G. Narasingha at http:wwwgosai.com/chaitanya/saranagati/html/nmj_articles/sacred_architecture/vastu For a Sanskrit text see Mayamata of Mayamuni, Trivandrum: Trivandrum Sanskrit Series, 1919. In most of the Vastishastras, Shiva is the revealer of the science of architecture. 3.Philippe Petit, Visionaries Dare to Take the Catwalks, New York Times, May 10, 2002, p. A33. 4.Michael Tobias book, Mountain People, Norman, London: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987, on the experiences associated with higher elevations, including Himalayas, is excellent. See also Michal Tobias and Harold Drasdo, The Mountain Spirit, London: V.Gollancz, 1980. Mircea Eliade has written about the archetype, for example in Patterns of Comparative Religion, tr. R. Sheed, New York: New American Library, 1974, pp 99-111. For a non-Himalayan example of thearchetypal mountain image in India see discussions of Arunachala mountain in Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi, Tiruvanamalai: Sri Ramanasram, 1978, pp. 14, 125, 178, 180-2, 228, 230, 416, 418, 509-11. Joseph Campbell, The Mythic Image, Princeton N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1974, p. 72 ff. On the experiential level the shamans trance at the center of early human religious life is often associated with heights. See also R. Bradley, The Archeology of Natural Places, London: Routledge, 1998. And E. Bernbaum, Sacred Mountains of the World, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998. Daniel Davenport's thesis, "The Development of Scale Independent, SelfSimilar Patterns in Khmer Architecture and the Utilised Landscape: And Exploration of Fractal Geometry Through GIS" for the University of Sydney, Australia, explores fractal structures in sacred space. See also Patrick George, "Counting Curvature: the numerical roots of North Indian temple architecture..." in the journal Res, vol. 34, Autumn, 1998, pp. 129-142. 5.George Michell, The Hindu Temple, p. 69. 6.Hollywood films sometimes use fractal programs to create visually realistic mountain ranges. Michael McGuires book, An Eye for Fractals, offers photographs

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 28 of 31

and a discussion of fractal mountains. 7.Ramesh Chandra Majumdar, Ancient India, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1964, pp. 462-3. 8.Ibid. 9.Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vol. I, p. 220. 10.Stella Kramrisch put the experience of multiple scale shikharas like this: One type of temple has the multiples of its own form set forth in the four directions; they ascend moreover from the corners, and each time to the same height as the Uromanjaris [the chest of the main shikhara]; they are accompamied furthermore in this massed competition towards the apex, by lesser replicas at the base, attaining to smaller fractions of the height while they reinforce on their own, lower levels the urgency of the ascent. Each of these multiple replicas has a neck, amalaka and finial [crowning ornament on the upper extremity]; while these terminate the single forms, they punctuate the striving of the entire mass of the superstructure toward the final point which lies beyond the trunk, whatever its height. p.211 With their curves the stone built shikharas of the Khajuraho temples arise and reiterate in their complex organization the perennial meaning of the Tabernacle of the forest. p. 207. 11.Huston Smith used the recursive patterns of three categories and a transcendent in his book the Religions of Man (later retitled as The Worlds Religions. Subash Kak wrote of this also in a paper at the website www.ee.lsu.edu/kak/wish-post Also, McKim Marriot wrote about this pattern in India Through Hindu Concepts: New Delhi: Sage Publications, 1990, pp. 1-41, as have I in an as-yet unpublished work, entitled "Other Shore Fractals.". 12.Rig Veda, I 164.46. 13.George Michell, The Hindu Temple, p. 61. 14.Significantly the English word altar is derived from a word meaning high as can be seen in the related word altitude. As axis of life joining earth to heaven this area may also have symbolisms of column, spine, tree, central towering link between realms. 15.Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vol. I p. 143. A tirtha is a place where the sacred crosses over into the world, within human reach. 16.Svetashvatara Upanishad 2.10. Olivelle tr. 17.Katha Upanishad 2.12. 18.Katha Upanishad 5.6. The Upanishadic view is that the unborn formless divine

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 29 of 31

Person, radiant, vast, the inner and outer of all, the source of all, including planets, beings, waters, plants, etc. All this is simply that Person-- rites, penance, prayer (brahman), the highest immortal, One who knows this, my friend hidden within the cave, cuts the knot of ignorance in this world. (Mundaka Upanishad 2.1.10) Though manifest, it is lodged in the cave, this vast abode named Aged. In it are placed this whole world; in it are based what moves or breathes. (Mundaka Upanishad 2.2.1) 19.Mundaka Upanishad 2.3.7. 20.George Michell, The Hindu Temple, p. 69. 21.This citation is from Stella Kramrisch. 22.Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vol. I, p. 253. 23.Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vol. I, p. 22. 24.Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vol. I, p. 70-71. George Michell, The Hindu Temple, p.70. There are also stories of an Asura purusha who receives a boon from Shiva-- always to be worshipped first. 25.Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, Vol. I, p. 7 26.Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, Vol. I, p. 71 27.Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vol. I, p. 7. 28.Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vol. I, p. 6. 29.The word Sanskrit purusha means pervading a city, and a divine city, such as Ayodhya (meaning the impregnable) is also represented symbolically in many temple plans. 30.Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vol. I, p. 47. 31.Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vol. I, p. 166. 32.Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vol. II, p. 301. 33.Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vol. II, p.302. 34.Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, Vol. II, p.303. 35.George Michell, The Hindu Temple, p. 68. 36.George Michell, The Hindu Temple, p. 73. "Hindu temples are not quite symmetrical: The legend goes that too much perfection would make the gods jealous.

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 30 of 31

But is the real reason not, in truth, that the 'perfection' of a work of art stems from controlled imperfections in the details, just as happens in Nature? Is it not because true perfection is sterile, while measured imperfection begets novelty?" Trinh Xuan Thuan, Chaos and Harmony, (tr. Axel Reisinger), New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. 37.George Michell, The Hindu Temple, p.73. 38.Stella Kramrisch, TheHindu Temple, vol. I. p.47. 39.Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vol. I p. 237 and ff. See also pp. 261 ff. 40.George Michell, The Hindu Temple, p. 61. 41.Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vol. I p. 8. 42.Authoritative sources for images suggesting fractal scaling in Hinduism include A Project on Agama, Alaya and Aradhana, Agama-Khosa (Agama Encyclopedia). S.K. Ramachandra Rao, Bangalore: Kalpatharu Research Academy Publication, 198?; Devendra Natha Shukla, Hindu Science of Architecture, 2 vols. Lucknow: VastuVanmaya-Sala, 1960. Devendra Natha Shukla, The Vastu Sastra, New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1998. 43.The erotic themes in these temples convey archetypal attraction, lifes potency and vitality, fecudity and creativity. as a force for protection. Life power expressed in the dramatic interplay of genders makes the stone figures strangely dynamic-- a generative flourish celebrating couplings, god and goddess genitals joined in grace. The energetic beauties of abundance in blissful rhythmic self-forgetfulness draw the pilgrim into contemplations lifes prolific force and mystery. 44.Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vol. I, 126-8. 45.It is the Seed of the Supreme Principle, in its triple aspect, as Bindu the point-limit between the unmanifest and the manifest, which is beyond perception; as Nada, in its subtle aspect as the basic substance or principal vibration; in its gross aspect, as Bija it is the seed of everything. Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vol. I, p. 128. 46.Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vol. I p. 15. 47.Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vol. i pp. 232, 253. 48. Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, vol. i. "When the building is completed and consecrated, its effigy in the shape of a golden man, the Prasada-purusha, is installed in the Golden jar, above the Garbhagriha, above the Shukanasa. The effigy is invested with all the Forms aned Principles of manifestation. While the Vastupurusha 'Existence' lies at the base of the temple and is its support, the Golden Purusha of the Prasada, its indwelling Essence, sum total of all of the Forms and

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

Hindu Temple Fractals

Page 31 of 31

Principles (tattva) or manifestation and their reintegration lies in the superluminous darkness of the Golden jar on top of the temple below the point limit of the manifest. In supernal radiance, the golden Purusha of the Vedic Altar (Taittiriya Samhita V.2.7.1) appears raised from the golden disc-- of the sun-- within the bottom layer of the Agni to the finial above the superstructure of the Hindu temple. The ascension of the Golden Purusha cancels the descent of the Vastupurusha. Within these two movements the Hindu temple has its being; its central pillar is erected from the heart of the Vastupurusha in the Brahmasthana, from the center and heart of Existence on Earth, and supports the Prasada Purusha in the Golden jar in the splendor of the Empyrean. Its mantle carries, imaged in its varied texture, in all directions all the forms and principles of manifestation towards the Highest Point above the body of the temple." Pp. 360-361.

http://liberalarts.iupui.edu/~wijackso/tempfrac/

10-Feb-13

You might also like

- Your Journey To The Basics of Quantum Realm Vol-I Edition 2: Your Journey to The Basics Of Quantum Realm, #1From EverandYour Journey To The Basics of Quantum Realm Vol-I Edition 2: Your Journey to The Basics Of Quantum Realm, #1Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Cause of Menopause & Mercury Is Not a PlanetFrom EverandThe Cause of Menopause & Mercury Is Not a PlanetRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Mathematics - Vedic Yoga, Seth and Multidimensional CosmologyDocument22 pagesMathematics - Vedic Yoga, Seth and Multidimensional CosmologyThad LekartovskiNo ratings yet

- Solar EcllipseDocument7 pagesSolar Ecllipsebhargavasarma (nirikhi krishna bhagavan)No ratings yet

- Secrets of Bharani NakshatraDocument4 pagesSecrets of Bharani NakshatraloshudeNo ratings yet

- LaserDocument10 pagesLaserBalkrishna DhinoraNo ratings yet

- Fractal Geometry As The Synthesis of Hindu Cosmology in Kandariya Mahadev Temple, KhajurahoDocument15 pagesFractal Geometry As The Synthesis of Hindu Cosmology in Kandariya Mahadev Temple, KhajurahoDr Abhas Mitra67% (3)

- Sadhguru Explores The Nature of Geometry and ArchitectureDocument1 pageSadhguru Explores The Nature of Geometry and ArchitectureAnonymous Dq88vO7aNo ratings yet

- Quantum EntanglementDocument11 pagesQuantum EntanglementSanket ShahNo ratings yet

- DNA Monthly Vol 5 No 3 March09Document13 pagesDNA Monthly Vol 5 No 3 March09pibo100% (1)

- DNA Monthly Vol 1 No 2 July05Document13 pagesDNA Monthly Vol 1 No 2 July05piboNo ratings yet

- Regis Hypothesis Concept en Anglais-SignedDocument33 pagesRegis Hypothesis Concept en Anglais-SignedNORMAND RÉGISNo ratings yet

- Sankhya PPTDocument36 pagesSankhya PPTkumaranNo ratings yet

- The Three Gunas - Tamas, Rajas and SattvaDocument2 pagesThe Three Gunas - Tamas, Rajas and Sattvacharan74No ratings yet

- Steinmetz Analogy Between Magnetic and Dielectric: PreprintDocument4 pagesSteinmetz Analogy Between Magnetic and Dielectric: PreprintbinaccaNo ratings yet

- Matrimandir Issue 1Document12 pagesMatrimandir Issue 1Mohit BansalNo ratings yet

- Vedic PhysicsDocument34 pagesVedic PhysicsKamalakarAthalyeNo ratings yet

- Pascal History PDFDocument32 pagesPascal History PDFraskoj_1100% (1)

- Chart Systems and NakshatrasDocument18 pagesChart Systems and Nakshatrassamm123456100% (1)

- MA Thesis BlasciocDocument65 pagesMA Thesis BlasciocRajamanitiNo ratings yet

- Suitable Astral GemsDocument19 pagesSuitable Astral GemsShyam S KansalNo ratings yet

- Barcellos - Fractal Geometry of MandelbrotDocument18 pagesBarcellos - Fractal Geometry of MandelbrotPatrícia NettoNo ratings yet

- Twelve Facets of Reality, The Jain Path To FreedomDocument102 pagesTwelve Facets of Reality, The Jain Path To FreedomkejalNo ratings yet

- Kemdrum and Othr StuffsDocument99 pagesKemdrum and Othr StuffschukiNo ratings yet

- Binar Sistem TheoryDocument28 pagesBinar Sistem TheoryDonald Carol0% (1)

- Nadi Astrology: 1 HistoryDocument4 pagesNadi Astrology: 1 Historydrago_rossoNo ratings yet

- THEORY SriYantraDocument26 pagesTHEORY SriYantraantonio_ponce_1No ratings yet

- Aspects of Jupiter & Neptune The Harmonious AspectsDocument2 pagesAspects of Jupiter & Neptune The Harmonious AspectsPhalgun Balaaji100% (1)

- The Magic of Ritual and Feng ShuiDocument7 pagesThe Magic of Ritual and Feng ShuiabbeycatNo ratings yet

- Extragalactic Astronomy and Cosmology PDFDocument2 pagesExtragalactic Astronomy and Cosmology PDFChristine0% (1)

- Brahmanda Purana - G.V.Tagare - Part 1 - Text PDFDocument392 pagesBrahmanda Purana - G.V.Tagare - Part 1 - Text PDFbvashramNo ratings yet

- Aintiram Part 2Document2 pagesAintiram Part 2malarvkNo ratings yet

- Planets& DiseasesDocument2 pagesPlanets& Diseasessurinder sangarNo ratings yet

- Review - The Book of RamDocument4 pagesReview - The Book of RamdeepakluniyaNo ratings yet

- Article 3 Vasthu and Feng ShuiDocument2 pagesArticle 3 Vasthu and Feng ShuiSamuel SanchezNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Sacred GeometryDocument6 pagesIntroduction To Sacred GeometryArnauNo ratings yet

- Y Aj Navalkya and The Origins of Pur An - Ic CosmologyDocument9 pagesY Aj Navalkya and The Origins of Pur An - Ic CosmologyJames L. KelleyNo ratings yet

- David Paul ColemanDocument13 pagesDavid Paul ColemanarpitaNo ratings yet

- 441 Heptad Gates PDFDocument1 page441 Heptad Gates PDFdanielmcosme5538No ratings yet

- Coaching Model: Jean Biacsi The SUCCESSDocument4 pagesCoaching Model: Jean Biacsi The SUCCESSCoach CampusNo ratings yet

- Vedic Enunciation of Geological Time ScaleDocument6 pagesVedic Enunciation of Geological Time ScalePurushottam GuptaNo ratings yet

- Inductive and Deductive TheoriesDocument5 pagesInductive and Deductive TheoriesMoureen NdaganoNo ratings yet

- Traditional Indian Architecture:: Hindu TemplesDocument18 pagesTraditional Indian Architecture:: Hindu TemplesFenil AndhariaNo ratings yet

- Hindu Theory: Hindu Philosophy and Its Imprint On ArchitectureDocument37 pagesHindu Theory: Hindu Philosophy and Its Imprint On ArchitectureMonisNo ratings yet

- 2133138-A Review Study On Architecture of Hindu TempleDocument7 pages2133138-A Review Study On Architecture of Hindu TempleAmit KumarNo ratings yet

- Chapter - Iv Temple ArchitectureDocument32 pagesChapter - Iv Temple ArchitectureAdam MusavvirNo ratings yet

- SriyantraDocument42 pagesSriyantraUday DokrasNo ratings yet

- STUPA As CosmosDocument39 pagesSTUPA As CosmosUday DokrasNo ratings yet

- Hindu TempleDocument15 pagesHindu TempleT Sampath KumaranNo ratings yet

- Jain TempleDocument25 pagesJain TempleUday Dokras100% (1)

- History of Temples of Historical Places OdishaDocument15 pagesHistory of Temples of Historical Places OdishaRiyaz KhanNo ratings yet

- HINDU TEMPLE ARCHITECTURE of BHARAT-SOME PDFDocument30 pagesHINDU TEMPLE ARCHITECTURE of BHARAT-SOME PDFSonal KaranjikarNo ratings yet

- T2 Temple Tech A BookDocument645 pagesT2 Temple Tech A Bookshanmuk .p100% (2)

- Some Distinguished Temples of Hinduism BOOKDocument298 pagesSome Distinguished Temples of Hinduism BOOKuday100% (1)

- A Mathematical TempleDocument32 pagesA Mathematical TempleUday Dokras100% (1)

- Hermeneutics and Phenomenology of BorobudurDocument46 pagesHermeneutics and Phenomenology of BorobudurUday DokrasNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature: Hinduism and Hindu ArchitectureDocument7 pagesReview of Related Literature: Hinduism and Hindu ArchitectureAllenJohnAltezaNo ratings yet

- Building Science of Indian Temple ArchitDocument12 pagesBuilding Science of Indian Temple ArchitRam SharmaNo ratings yet

- Borobudur and The Experience of MeaningDocument127 pagesBorobudur and The Experience of MeaningUday DokrasNo ratings yet

- Building Science of Indian Temple Architecture: Shweta Vardia and Paulo B. LourençoDocument12 pagesBuilding Science of Indian Temple Architecture: Shweta Vardia and Paulo B. LourençoGyandeep JaiswalNo ratings yet

- Vaastu - 1. Vastu IntroductionDocument5 pagesVaastu - 1. Vastu IntroductionDisha TNo ratings yet

- Vipassana CritiqueDocument30 pagesVipassana CritiqueDisha TNo ratings yet

- Abhyanga - Ayurvedic Oil MassageDocument11 pagesAbhyanga - Ayurvedic Oil MassageDisha TNo ratings yet

- Overcoming Common Challenges To FitnessDocument6 pagesOvercoming Common Challenges To FitnessDisha TNo ratings yet

- Food Guidelines For Different Doshas - Ayurvedic ConceptDocument6 pagesFood Guidelines For Different Doshas - Ayurvedic ConceptDisha TNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Soaking Nuts and SeedsDocument2 pagesBenefits of Soaking Nuts and SeedsDisha TNo ratings yet

- Jainism - UpdeshprasadDocument424 pagesJainism - UpdeshprasadDisha TNo ratings yet

- Taurine For VegansDocument1 pageTaurine For VegansDisha TNo ratings yet

- Vitamin A For VegansDocument1 pageVitamin A For VegansDisha TNo ratings yet

- Jainism - CelibacyDocument5 pagesJainism - CelibacyDisha TNo ratings yet

- High ALA Sources: Home - Site MapDocument2 pagesHigh ALA Sources: Home - Site MapDisha TNo ratings yet

- Iron For VegansDocument6 pagesIron For VegansDisha TNo ratings yet

- CH 2 Daily Routines Exercise YogaDocument29 pagesCH 2 Daily Routines Exercise YogaDeepakkmrgupta786No ratings yet

- Calcium and Vitamin D For VegansDocument14 pagesCalcium and Vitamin D For VegansDisha TNo ratings yet

- Choline For VegansDocument7 pagesCholine For VegansDisha TNo ratings yet

- Carnosine For VegansDocument2 pagesCarnosine For VegansDisha TNo ratings yet

- Vitamins B2 & B6 For VegansDocument1 pageVitamins B2 & B6 For VegansDisha TNo ratings yet

- manuelWalkNewEnergy1 3Document24 pagesmanuelWalkNewEnergy1 3soaremihaela88No ratings yet

- Spirituality Is India's Contribution To The WorldDocument35 pagesSpirituality Is India's Contribution To The WorldAnushka SaxenaNo ratings yet

- OremusDocument1 pageOremusKyle Benedict OccidentalNo ratings yet

- Evolutionist Manifesto - Book For Change - Sundar Kumar Sharma - Nepal - Documents in PressDocument14 pagesEvolutionist Manifesto - Book For Change - Sundar Kumar Sharma - Nepal - Documents in Presssundarksharma100% (1)

- Stress Management: Ashtanga YogaDocument29 pagesStress Management: Ashtanga YogaRaj BharathNo ratings yet

- Sri Guruji A Living Example of Spiritual NationalismDocument218 pagesSri Guruji A Living Example of Spiritual NationalismVivekananda KendraNo ratings yet

- Science of Mind - Workbook - FoundationsDocument236 pagesScience of Mind - Workbook - Foundationsshane1800100% (10)

- Revealing The Soul - IIDocument119 pagesRevealing The Soul - IIRabbi Yosef Yitzchok SerebryanskiNo ratings yet

- YTT-RYS 200 Application FormDocument5 pagesYTT-RYS 200 Application FormtwerryNo ratings yet

- Is Shamanism A ReligionDocument28 pagesIs Shamanism A Religionbheim108No ratings yet

- (Hinduism) Swami Vivekananda - The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda (Total 9+1 Volumes) - Advaita Ashrama (2020) PDFDocument4,112 pages(Hinduism) Swami Vivekananda - The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda (Total 9+1 Volumes) - Advaita Ashrama (2020) PDFAkshay NarasimhaNo ratings yet

- Iyn 8Document64 pagesIyn 8Michela Brígida RodriguesNo ratings yet

- The Truth of The Spirit World Translated BT Nalaka WeerasuriyaDocument4 pagesThe Truth of The Spirit World Translated BT Nalaka WeerasuriyaNalaka Sajiva WeerasuriyaNo ratings yet

- Yoga (Astanga Marga)Document11 pagesYoga (Astanga Marga)Ramachandra Raju Kalidindi0% (1)

- Zen of Steve Vai by Acharya BabanandaDocument39 pagesZen of Steve Vai by Acharya BabanandaKim Kongfu Panda100% (4)

- Kirael Awakening Your Spiritual BlueprintDocument6 pagesKirael Awakening Your Spiritual BlueprintMeaghan MathewsNo ratings yet

- Learning Activity Sheets Introduction To World Religions and Belief SystemDocument56 pagesLearning Activity Sheets Introduction To World Religions and Belief SystemAngelica Caranzo LatosaNo ratings yet

- June 2019 Solstice CADocument80 pagesJune 2019 Solstice CAataktos100% (1)

- Five Keys of Prana VidyaDocument3 pagesFive Keys of Prana VidyasipossNo ratings yet

- PeaceDocument528 pagesPeacedubrovnik2012No ratings yet

- Principles of Zen Buddhism in A Nutshell (Appamada)Document1 pagePrinciples of Zen Buddhism in A Nutshell (Appamada)Amalie WoproschalekNo ratings yet

- Autobiography of Swami JnananandaDocument45 pagesAutobiography of Swami Jnananandalifesoneric100% (5)

- Mansur Al-Hallaj - Wikiquote PDFDocument5 pagesMansur Al-Hallaj - Wikiquote PDFSKYHIGH444No ratings yet

- Yogacharya T Krishnamacharya As A Sanskrit ScholarDocument19 pagesYogacharya T Krishnamacharya As A Sanskrit ScholarSrinivasaraghava SridharanNo ratings yet

- Baba RamdevDocument7 pagesBaba Ramdevamit singhNo ratings yet

- Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga: "Yoga Begins With Listening." Richard FreemanDocument4 pagesAshtanga Vinyasa Yoga: "Yoga Begins With Listening." Richard FreemanMariana EllaiNo ratings yet

- Engaging The Revelatory Realm of Heaven by Paul Keith DavisDocument128 pagesEngaging The Revelatory Realm of Heaven by Paul Keith Davisfrancofiles100% (17)

- Cloud Banks of Nectar - Longchenpa - David George WarrenDocument4 pagesCloud Banks of Nectar - Longchenpa - David George WarrenArsene LapinNo ratings yet

- Sounds Islamic?: Muslim Music in BritainDocument301 pagesSounds Islamic?: Muslim Music in BritainAfrizal lNo ratings yet

- Jyotish Tantra RahasyamDocument4 pagesJyotish Tantra RahasyamPawan Madan100% (1)