Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1 - 2 - 1.2 Why Do People Risk Everything For Democracy - (18 Min)

Uploaded by

defensormalditoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1 - 2 - 1.2 Why Do People Risk Everything For Democracy - (18 Min)

Uploaded by

defensormalditoCopyright:

Available Formats

In my travels through developing, what used to be called developing countries in particular, we now call them emerging market countries

or post-communist countries in every continent of the world. I have been struck and we will see quite a wealth of public opinion survey data that I think will underscore the extent to which democracy has become a broadly-shared aspiration in the world even a universal value. And the question that has very substantially motivated my writing and my desire to be supportive, to be engaged to see the United States and other democracies become a partner in trying to facilitate and improve the functioning of democracy around the world or to assist its emergence where it doesn't exist. My motivation, in part, has been a response to what I have seen in terms of less fortunate societies that have long been trapped in authoritarianism and massive political and social inequality and injustice. And in those circumstances of considerable repression and often very great risk for decent for independent political opposition and mobilization, the question arises, why do people take these risks? Why did Nelson Mandela engage in a form of political resistance that sent him to prison for 29 years much of it spent here on the desolate and forbidding terrain of Robben Island outside of Cape Town? the home of a prison camp in which many of the leaders of the African National Congress, the ANC, spent the prime of their life. How did it come to be that Nelson Mandela ultimately triumphed by emerging out of prison, prison? A proud and principled, but yet pragmatic man, who lead the negotiations with the Apartheid regime in South Africa for one of the most successful transitions to democracy. A transition that was notably peaceful in circumstances that could have turned violent in the context of South African completed with the successful national election in 1994. What led this extraordinarily courageous, and principled, and humane, human rights and democracy activist and intellectual, in the center of these photographs here, Liu Xiaobo.

To take the risks he took to challenge the authoritarian nature of rule in China and organize a petition for freedom in China, Charter 08, that was signed, that was signed by thousands of Chinese intellectuals, civil society leaders dissidents, activists and people who simply want to see the emergence of a free, open democratic society in their country. Why would a nuclear physicist of the stature and security the fame and privilege of Andrei Sakharov in the Soviet Union turn from his privileged position in the Soviet physical sciences, the father of the Soviet atom bomb to the campaign for peace and human rights in the Soviet Union, and the ostracism that he suffered as a result? What motivates individuals like this to take great risks for freedom and democracy? We see this story so universally around the world and tragically the price that is sometimes paid by people who take leadership positions in the struggle for democracy. Like the Mongolian politician and civic leader, Zorig Sanjaassuren, who was a prominent Mongolian politician and youth leader who helped to make the 1990 democratic revolution in Mongolia as the Soviet Union was decomposing and the movement for freedom was spreading throughout the communist world. And who tragically was assassinated at the age of 36, in the prime of his life, by unknown assailants, leaving behind a wide number Mongolian youth who had been inspired by him and who've carried on his work and his Civil Society Organization, the Zorig Foundation for Advancing Democracy. Or, of course, the legacy of one of the great pro-democracy leaders of our time. someone who I think stands, in terms of historical perspective with the vision, the courage, and the international prestige and inform, and inspiration that, Nelson Mandela has achieved from his experience in South Africa, namely Aung San Suu Kyi. When you meet individuals like Daw Suu Kyi, one cannot help become, but become inspired by their vision, the strength and conviction of their values the degree of strategy and political reflection that has to go into the calculations and choices they make in a transitional period.

Understanding that politics can not only be about pure morality that as we'll see when we study transitions to democracy. The transitional politics is very much about having to make difficult and painful choices. It's not only about inspiration, but it's about strategy and organization. and the great democratic leaders of our times who have helped to bring about democracy in difficult circumstances have been leaders who combined moral prestige and integrity with a strong dose of pragmatism, of generosity, of magnanimity, of reaching out across polarized lines. And of creating a new type of dialogue, and a system of what the great Yale political scientist, Robert Dahl, called mutual security. This is, I believe, part of the project that Aung San Suu Kyi is now engaged in in Burma, that may heavily affect whether Burma succeeds in its transition to democracy. Burma is privileged to have an extraordinary array of civil society leaders, who have paid dearly as Daw Suu Kyi did. having spent 15 of 20 years of her life under confinement to her house, under house arrest in very difficult and emotionally trying circumstances. But so many Burmese lost the prime of their youth in jail, or even lost their lives in repression. Here we see, on the left-hand side, is student leader. Ko Jimmy is his nickname. On the right, one of the most important leaders of the student movement for democracy in Burma, when it rose up in 1988, against the dictatorship of General Ne Win. On the right, we see Min Ko Naing who co-founded the All Burma Federation of Student Unions in 1988, in the uprising against the military dictatorship. And then, himself, spent 15 years in prison as a political prisoner. And then when he was released, he and his colleagues like Ko Jimmy founded the 88 Generation Students Group, one of the most important networks and advocacy groups for a full democratic transition and the remaking of Burma as a democratic society. How do people like this risk so much for democracy? And how do they emerge out of prison

having lost the prime of the their youthful years with the freedom from bitterness and the focus on the practical challenges of democracy building that they indeed have. If we can understand their experience and draw from their model and their personal values, we might do much to advance democracy around the world and build a global network of democrats who are seeking the common goal of free and accountable government around the world. Here is a woman I've come to know in my travels. and through her presence in the United States, unfortunately in exile now, who's been called the Aung San Suu Kyi of Ethiopia. Birtukan Mideksa is her name. And she is a judge who simply tried to enforce the law in a neutral and dispassionate way as a young judge in Ethiopia, and ran afoul of an authoritarian regime that wanted the judiciary to be pliant and accept instructions from the ruling authoritarian regime. Refusing to accept those instructions, believing in the principle of the rule of law, that no one is above the law, and everyone is equal before the law. Birtukan left the judiciary to form an opposition party and challenge the incumbent government in national elections. For this act of great temerity, she, herself, became a political prisoner, and spent several years in prison. Why do people like this, people with so much to, to lose with the opportunity to become comfortable in the existing structure, with young children and families, that themselves may be vulnerable, why do they take these great risks? Why did the leader of the Zimbabwean political opposition, Morgan Tsvangirai, when he suffered a death, a series of death threats in his efforts to lead and unite the political opposition in a challenge to the authoritarian rule, now more than 30 years long of President Robert Mugabe. why did Tsvangirai continue in this campaign for democracy in Zimbabwe, when he suffered a very narrow escape from an assassination attempt on at least one and possibly several occasions? When his wife was killed in an automobile crash, in what some people believe was

possibly another assassination attempt. And when his supporters have suffered the massive retaliation of physical violence, torture, and intimidation that was visited upon them in the 2008 presidential election campaign, which most independent observers believe the Tsvangirai's MDC, his opposition party would have won. Many people would have quit at that point. Why did Tsvangirai continue to the point where at the moment, he shares power very uneasily with Mugabe and the ruling ZANU-PF party in a difficult and stressful coalition government. We will be looking at the democratic changes that have happened in the Arab world and the extraordinary stories of people like this young woman, Esraa Abdel Fattah of Egypt, a leader of the April 6th Youth Movement, launched in 2008, to support the demand of Egyptian workers for better wages and basic rights as workers. It was Esraa's innovation to launch the general strike on Facebook that rallied so many young Egyptians to the cause and created the platform for a whole new movement and a whole new generation of political action in Egypt that helped to lay the path, the tools, the groundwork for that fed into the Arab Spring. And that helped, eventually helped bring down the Mubarak regime in the revolution that toppled him in February of 2011. Esraa, herself has been harassed, has been sent to prison has been threatened. Why do civil society leaders like this with so much of their lives ahead continue on in the face of risks for this abstract principle that is democracy? Here, we have another Arab activist, Abduljalil Al-Singace, someone we came to know well. Here at Standord University, he spent three weeks at the center I direct here, the Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law as a summer fellow listening to some of the same lectures that you will listen to in this course. Engaging peers from around the world who are trying to campaign for and build democracy in the hope in the same way that I hope you will engage one another in this course. And who, after the eruption of the Arab Spring at the end of 2010 and the beginning of 2011 lead and helped to organize peaceful protests in the round

about square of his own capital of Bahrain, the capital city of Manama. And he too suffered the consequences and in a very serious way. Only recently having been sent to life imprisonment for the simple act of peacefully organizing protests calling for political change in his country. Here's a man who you can see suffers some physical disabilities and yet was subjected to brutal torture by the government and state security operators of Bahrain. Why do individuals like this, living a comfortable, in this case, as a Professor of Engineering at the University in Bahrain, take the risks they do for this abstract concept called democracy?

You might also like

- Patinas - Metal+mettleDocument7 pagesPatinas - Metal+mettledefensormaldito100% (2)

- Hyperbolic Paraboloid #2 - Evelyn MarkaskyDocument3 pagesHyperbolic Paraboloid #2 - Evelyn MarkaskydefensormalditoNo ratings yet

- Fórmulas de PatinasDocument4 pagesFórmulas de Patinasdefensormaldito100% (2)

- Tesoura Ourives e Solda P Joias de Prata e Armação de ÓculosDocument4 pagesTesoura Ourives e Solda P Joias de Prata e Armação de ÓculosdefensormalditoNo ratings yet

- The Sherman Micro FoldDocument5 pagesThe Sherman Micro Folddefensormaldito0% (1)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Michael Gallagher, Paul Mitchell-The Politics of Electoral Systems (2008)Document689 pagesMichael Gallagher, Paul Mitchell-The Politics of Electoral Systems (2008)Hari Madhavan Krishna Kumar100% (2)

- Differences Between Spanish Colonial Government andDocument10 pagesDifferences Between Spanish Colonial Government andLorna Dagasdas Magbanua100% (1)

- Constitutional Law 2 CASES (III)Document398 pagesConstitutional Law 2 CASES (III)Gerard TinampayNo ratings yet

- IPU Report Parliament and The Budgetary Process For English Speaking African ParliamentsDocument98 pagesIPU Report Parliament and The Budgetary Process For English Speaking African ParliamentsMarya AdjibodouNo ratings yet

- (Walter Laqueur) Fascism Past, Present, Future PDFDocument273 pages(Walter Laqueur) Fascism Past, Present, Future PDFRejane Carolina Hoeveler100% (1)

- The Informal Economy - Portes Haller 2004Document23 pagesThe Informal Economy - Portes Haller 2004Martin RiveroNo ratings yet

- Ecuadorian General Election, 1978-1979Document5 pagesEcuadorian General Election, 1978-1979ХристинаГулеваNo ratings yet

- Michal Eskenazi - The American Discourse On The Arab Spring and Its Relevance To IsraelDocument12 pagesMichal Eskenazi - The American Discourse On The Arab Spring and Its Relevance To Israelngoren3163No ratings yet

- Lauren Movius - Cultural Globalisation and Challenges To Traditional Communication TheoriesDocument13 pagesLauren Movius - Cultural Globalisation and Challenges To Traditional Communication TheoriesCristina GanymedeNo ratings yet

- 02 The Rule of Law - An OverviewDocument44 pages02 The Rule of Law - An OverviewtakesomethingNo ratings yet

- Local Government AdministrationDocument55 pagesLocal Government AdministrationApple Panganiban100% (3)

- Chris Hedges Inverted TotalitarianismDocument2 pagesChris Hedges Inverted TotalitarianismAlice PaulNo ratings yet

- Defining Defining Capitalism, Communism, Fascism, SocialismDocument1 pageDefining Defining Capitalism, Communism, Fascism, SocialismRaudah HalimNo ratings yet

- 201437737Document68 pages201437737The Myanmar Times75% (4)

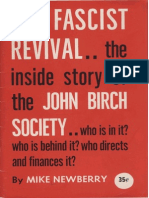

- Newberry The Fascist Revival The Inside Story of The John Birch SocietyDocument52 pagesNewberry The Fascist Revival The Inside Story of The John Birch SocietyKelly LincolnNo ratings yet

- Kenneth Baynes: Deliberative Democracy and The Limits of LiberalismDocument16 pagesKenneth Baynes: Deliberative Democracy and The Limits of LiberalismRidwan SidhartaNo ratings yet

- The French RevolutionDocument5 pagesThe French RevolutionX CrossNo ratings yet

- Norzagaray College: Midterm Examination in Rizal Life, Works, and WritingsDocument3 pagesNorzagaray College: Midterm Examination in Rizal Life, Works, and WritingsRelec RonquilloNo ratings yet

- Local Voice April 2011Document24 pagesLocal Voice April 2011MoveUP, the Movement of United ProfessionalsNo ratings yet

- Leon Trotskii Collected Writings 1934 1935Document489 pagesLeon Trotskii Collected Writings 1934 1935david_lobos_20No ratings yet

- Bureaucratic Politics and The Fall of Ayub KhanDocument19 pagesBureaucratic Politics and The Fall of Ayub KhanUsman Ahmad100% (1)

- The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and AbroadDocument2 pagesThe Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and AbroadRidho Shidqi MujahidiNo ratings yet

- Hilary ClintonDocument15 pagesHilary ClintonKenric WardNo ratings yet

- Tibet - The Myth of Shangri-LaDocument4 pagesTibet - The Myth of Shangri-LasapientpenNo ratings yet

- ANC Candidate List 2019 ElectionsDocument28 pagesANC Candidate List 2019 ElectionsPrimedia Broadcasting67% (3)

- Test Bank For Amgov Long Story Short 1st Edition Christine BarbourDocument20 pagesTest Bank For Amgov Long Story Short 1st Edition Christine BarbourDonald Knapp100% (40)

- NGOs of KazakhstanDocument69 pagesNGOs of KazakhstanDanteKant0% (1)

- Naming The Moment1Document98 pagesNaming The Moment1Javier AmescuaNo ratings yet

- Andrzej Paczkowski, Jane Cave-The Spring Will Be Ours - Poland and The Poles From Occupation To Freedom (2003)Document600 pagesAndrzej Paczkowski, Jane Cave-The Spring Will Be Ours - Poland and The Poles From Occupation To Freedom (2003)Ale Tapia San Martín100% (1)

- Greek Demo ReadingDocument9 pagesGreek Demo Readingapi-234531449No ratings yet