Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Vaclav Havel: Language and Peace

Uploaded by

arbarne2Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Vaclav Havel: Language and Peace

Uploaded by

arbarne2Copyright:

Available Formats

14 Oct 2011 Vaclav Havel: Language and Peace There has never been a time when a sense of the

importance of words was not present in human consciousness (A Word About Words.) This statement by former President Vaclav Havel, made in his 1989 acceptance speech for the Peace Prize of the German Booksellers Association, is crucial in understanding the elements of Havels democratic and literary successes; while also addressing the power human beings have in their ability to exercise the miracle of human speech. (A Word About Words.) As a politician, activist, playwright, poet, essayist, etc, Havel, himself, used language as a noble tool in preserving his own human dignity, as well as in his accomplishments towards human rights and world peace. Havels credibility can be measured not only in his revolutionary influence in the democratization of Czechoslovakia, but also by his contributions to the global human rights movement as well as in his diverse literary works. In his essay, The Power of the Powerless, Havel illustrates the ambiguity of words and the effects that occur when our words have multiple meanings. He gives an example of a green grocer, who has on display in his store window, the slogan, Workers of the world, Unite! For five small words, this phrase actually speaks measures when its implications are considered. Havels argument on the ambiguity of language begins here; to the totalitarian state, this slogan is symbolic of the arrogant state of control it exercises over the individual. However, in the perspective of the grocer, these words mean: I behave in the manner expected of

me. I can be depended upon and am beyond reproach. I am obedient and therefore I have the right to be left in peace. The slogan also implies another reality; which is the grocers fear of prosecution if he protests the display of the slogan. Havels use of this example shows a mundane aspect of life in a society, yet the message and the symbolism of the slogan to each party involved is clear. Havel takes his argument one step further and depicts the scenario if the grocer decided to use his voice to object the slogan. The grocer would be remaining loyal to his conscience, but would face retributions by the state. However, the value in this option would be that he gives his freedom a concrete significance. His revolt is an attempt to live within the truth. Another, more significant effect of his revolt is that it illegitimates the institution by exposing it for its true arrogance. Drawing from his personal experience, Havel spoke of a time when his German colleagues would not associate with him because he was considered an enemy of his government. Havel said, even in those days, it was I who pitied them, since it was not I but they who were voluntarily renouncing their freedom. This quote represents the core of Havels argument, and the measure of his moral integrity as a whole. Havel would rather sacrifice material liberties than the ideologies that define his character. Even though his words were in disobedience with the state, he never lost his own freedom of thought because he chose not to betray his conscience regardless of the repercussions he faced. Throughout his resistance to the Communist government Havel was sentenced to prison several times. Even in those years of imprisonment, he was

remained free in his thoughts. He continued to use words for self-expression by writing to his wife in Letters to Olga. Similarly to the hypothetical green grocer scenario, Havel proved that the true overcoming force is the one that remains in truth, even if it has to make a sacrifice to remain earnest. Havel Another personal example of Havels literature holding a prominent role in his ideologies is in the ban of his plays from Czech theater in 1968, after the Prague Spring ended. Often based on absurd themes, his plays were being performed in New York City during the time of their ban in Czechoslovakia. Once again, Havels words prevailed. Although the plays did not get performed in his country, his words were alive somewhere else, so he was still communicating effectively to an audience. In his speeches, Havel used language to articulate the lessons we can learn from our histories. In 1989, upon receiving the Peace Prize of the German Booksellers Association, Havel gave an acceptance speech entitled A Word About Words, in which he boldly defines words as the very source of our being. He compels the argument that as language is the framework for our civilization, we must be aware of the implications of our word choices, especially considering the ambiguous nature of language. Havel pays particular attention to the ways in which words and peace are correlated. The meaning of our language is so complex that in order to create peace we have to be responsible and humble when choosing our words. , We have tried incessantly to address that which is concealed by mystery, and

influence it with our words. This statement rings true one of the basic principles of human nature: our ability to use reason and logic to find answers. However, Havel makes

a crucial point in this speech by pointing out that, although humans are incredibly capable of cognitive thinking, there are some phenomena belonging to the Laws of Nature which are outside of our realms of understanding. When our human intelligence is too limiting to give us all of the answers we want, we create theories in attempts at reaching an understanding of the unknown. This is the point in which the words we choose to use have the power to change history. Another aspect of Havels democratic success through the use of language is his belief that dialogue is central to the development of peace. His founding of the Forum 2000 conference is indicative of his earnest dedication to the dialectic method for promoting democratization and tolerance in the world. I have said again and again how it would be good if intelligent people, not only from the various ends of the earth, different continents, different cultures, from civilization's religious circles, but also from different disciplines of Human knowledge could come together somewhere in calm discussion. At the Forum 2000 conference of 2011, discussions of democracy brought together delegates from around the globe in a peaceful recognition of mutual respect and appreciation. Not only was the importance of word choice obvious in the panel discussions between leaders coming from differing cultures, it was also important because of the obvious language barrier issue. Translators were crucial players in the forum discussion, and once again it became clear just how much we rely on language to keep the peace in our society. In a Forum 2000 debate regarding freedom of speech and dialectics in religion, Egyptian journalist and delegate Shahira Amin spoke of an Egyptian law student in

Alexandria who was explicitly arrested and sentenced to three years in prison for writing anti-religious posts on an internet blog in 2007. The issue could not be more relevant to Havels original motivation for the Forum 2000 foundation, and remains present proof that Havels writings and discussion topics are crucial to understand. Our words do impact history, and the words outlining governmental policies may not always align with the words we feel are true in our hearts. The urgency of President Havels insight, responsibility for and toward words is a task which is intrinsically ethical, is crucial to recognize. Whether in politics, literature, or the slogans on our windows that bore of mundane essence, words and literature, as created by mankind, are the ultimate tools and weapons at our discretion. It is through words which we create the fundamental laws and institutions of our society, through words we have come to understand our religions, and most importantly, it is through words which human beings are capable of causing turmoil as well as triumph.

You might also like

- Deadly UnnaDocument2 pagesDeadly Unnaroflmaster22100% (2)

- Peter Sloterdijk Nietzsche ApostleDocument92 pagesPeter Sloterdijk Nietzsche ApostleLucas Girard88% (8)

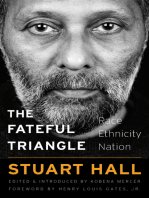

- Representation by Stuart HallDocument5 pagesRepresentation by Stuart HallElmehdi MayouNo ratings yet

- Humor PDFDocument11 pagesHumor PDFJohn SanchezNo ratings yet

- Human RightsDocument66 pagesHuman RightssergeNo ratings yet

- An Essay On The Inequality of The Human Races - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument4 pagesAn Essay On The Inequality of The Human Races - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopedialimechipNo ratings yet

- Henrik Ibsen's Life and WritingDocument11 pagesHenrik Ibsen's Life and WritingDaniel Lieberthal100% (1)

- Havel - The Anatomy of HateDocument9 pagesHavel - The Anatomy of HateOtilia IoanaNo ratings yet

- Nietzsche Will To PowerDocument79 pagesNietzsche Will To PowerToh Qin KaneNo ratings yet

- William Graham Sumner: "What The Social Classes Owe ToDocument9 pagesWilliam Graham Sumner: "What The Social Classes Owe ToAnurag KureelNo ratings yet

- Lord Ewald's final doubts about mechanical natureDocument23 pagesLord Ewald's final doubts about mechanical natureSydney TyberNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Amusing Ourselves To Death Book Review 1Document7 pagesRunning Head: Amusing Ourselves To Death Book Review 1Kennedy Gitonga ArithiNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument210 pagesUntitledBen MilesNo ratings yet

- The Art of Uncertainty: A Scrutiny in Theatre of Michael FraynDocument8 pagesThe Art of Uncertainty: A Scrutiny in Theatre of Michael FraynIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Great Piece by John KayDocument2 pagesGreat Piece by John KaysanjayjogsNo ratings yet

- We Live in a Contaminated Moral Environment SpeechDocument3 pagesWe Live in a Contaminated Moral Environment SpeechTheresa MurilloNo ratings yet

- Norris CavellDocument18 pagesNorris Cavellpaguro82No ratings yet

- Etc 75-3-4 Levinson Aldous Huxley and General SemanticsDocument9 pagesEtc 75-3-4 Levinson Aldous Huxley and General SemanticsHoneyLopesNo ratings yet

- Love and Law Short VersionDocument11 pagesLove and Law Short Versionrajgopal27No ratings yet

- Texts of Value Outlive and Transcend The Context in Which They Were CreatedDocument3 pagesTexts of Value Outlive and Transcend The Context in Which They Were CreatedZaeed HuqNo ratings yet

- Wellness Beyond Words: Maya Compositions of Speech and Silence in Medical CareFrom EverandWellness Beyond Words: Maya Compositions of Speech and Silence in Medical CareNo ratings yet

- 43 Orwell's Politics and The English LanguageDocument7 pages43 Orwell's Politics and The English Languagecmarchiani100% (1)

- Sage V For VendettaDocument25 pagesSage V For VendettaImadNo ratings yet

- Orwell's 1984 Analyzed Through Marxist and Psychoanalytic LensesDocument8 pagesOrwell's 1984 Analyzed Through Marxist and Psychoanalytic LensesTrailer Guys100% (1)

- CT200 Short Paper Hegeland LanguageDocument6 pagesCT200 Short Paper Hegeland LanguagePedro Javier RolónNo ratings yet

- Language, History, and Class Struggle Ni David McNallyDocument6 pagesLanguage, History, and Class Struggle Ni David McNallyJoanna Marie OliquinoNo ratings yet

- Eva Duarte de PerónDocument5 pagesEva Duarte de PerónAye GarneroNo ratings yet

- Reading Silence (Excerpt From Skepticism and Redemption:: The Political Enactments of Stanley Cavell)Document21 pagesReading Silence (Excerpt From Skepticism and Redemption:: The Political Enactments of Stanley Cavell)FastBlitNo ratings yet

- Miller Robert L The Linguistic Relativity Principle and HumbDocument130 pagesMiller Robert L The Linguistic Relativity Principle and HumbMuhammad LuthendraNo ratings yet

- The Humiliation of The WordDocument6 pagesThe Humiliation of The Worde4unityNo ratings yet

- Bein 1964Document40 pagesBein 1964Selva TorNo ratings yet

- Engl 1010 Rhetorical AnalysisDocument4 pagesEngl 1010 Rhetorical Analysisapi-242228959No ratings yet

- Language and Ideology, Language in IdeologyDocument5 pagesLanguage and Ideology, Language in IdeologyBen WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Herder, Humboldt, Heidegger - Language As World-Disclosure - Issue 108 - Philosophy NowDocument4 pagesHerder, Humboldt, Heidegger - Language As World-Disclosure - Issue 108 - Philosophy NowBanderlei SilvaNo ratings yet

- McNally Language History and Class StruggleDocument9 pagesMcNally Language History and Class StruggleChokkon DixNo ratings yet

- Compare Contrast Essay TopicsDocument4 pagesCompare Contrast Essay Topicsafibyoeleadrti100% (2)

- Language George OrwellDocument4 pagesLanguage George OrwellIuliana CostachescuNo ratings yet

- Handout 1 - IdentityDocument7 pagesHandout 1 - IdentityVere Veronica VereNo ratings yet

- Politics and The Political The Mythical Superposition of Two Political StatesDocument12 pagesPolitics and The Political The Mythical Superposition of Two Political StatesFederico SantacruzNo ratings yet

- Tok ExhibitionDocument4 pagesTok ExhibitionPhilip GöserNo ratings yet

- Rhetorical CitizenshipDocument11 pagesRhetorical CitizenshipLauren Cecilia Holiday Buys100% (1)

- PORCHEDDU, A. Orwell and The Power of LanguageDocument3 pagesPORCHEDDU, A. Orwell and The Power of LanguageNicole DiasNo ratings yet

- Listening To LanguageDocument18 pagesListening To LanguagemychiefNo ratings yet

- The Problems of Language in Cross Cultural StudiesDocument22 pagesThe Problems of Language in Cross Cultural StudiesMuhammedNo ratings yet

- Mustapha Khayati Captive Words Preface To A Situationist DictionaryDocument6 pagesMustapha Khayati Captive Words Preface To A Situationist DictionaryMiguel SoutoNo ratings yet

- Political Correctness Synthesis EssayDocument2 pagesPolitical Correctness Synthesis EssayViidra1No ratings yet

- Discourse of Denunciation: A Critical Reading of Chinua Achebe'S Man of The PeopleDocument15 pagesDiscourse of Denunciation: A Critical Reading of Chinua Achebe'S Man of The PeopleMaryam SàddiqäNo ratings yet

- Lyric Orientations: Hölderlin, Rilke, and the Poetics of CommunityFrom EverandLyric Orientations: Hölderlin, Rilke, and the Poetics of CommunityNo ratings yet

- Havel's Dual Legitimacy of Soviet DissentDocument8 pagesHavel's Dual Legitimacy of Soviet DissentMaya BoyleNo ratings yet

- Noam ChomskyDocument15 pagesNoam ChomskyAnonymous lHYiPmRfNo ratings yet

- Daniel Defoe S Moll Flanders and Paulo Coelho S Eleven Minutes - A Comparative Study PDFDocument115 pagesDaniel Defoe S Moll Flanders and Paulo Coelho S Eleven Minutes - A Comparative Study PDFTothMonikaNo ratings yet

- Deleuze's Schizoanalytic Approach to LiteratureDocument27 pagesDeleuze's Schizoanalytic Approach to LiteratureN IncaminatoNo ratings yet

- Deborah Cameron On WhorfDocument4 pagesDeborah Cameron On Whorfcorto128100% (1)

- 2013 Peter Thompson The Privatization of Hope - Ernst Bloch and The Future of UtopiaDocument331 pages2013 Peter Thompson The Privatization of Hope - Ernst Bloch and The Future of UtopiacjlassNo ratings yet

- Adriana Cavarero Feminist PhilosophyDocument6 pagesAdriana Cavarero Feminist PhilosophybesciamellaNo ratings yet

- How our words influence thought: the principle of linguistic relativityDocument3 pagesHow our words influence thought: the principle of linguistic relativityThalassa MarisNo ratings yet

- Untitled DocumentDocument2 pagesUntitled Documentapi-359544595No ratings yet

- Poetry and PoliticsDocument21 pagesPoetry and Politicshotrdp5483No ratings yet

- Financial Accounting and ReportingDocument31 pagesFinancial Accounting and ReportingBer SchoolNo ratings yet

- Electric Vehicles PresentationDocument10 pagesElectric Vehicles PresentationKhagesh JoshNo ratings yet

- Barnett Elizabeth 2011Document128 pagesBarnett Elizabeth 2011Liz BarnettNo ratings yet

- Plo Slide Chapter 16 Organizational Change and DevelopmentDocument22 pagesPlo Slide Chapter 16 Organizational Change and DevelopmentkrystelNo ratings yet

- Daft Presentation 6 EnvironmentDocument18 pagesDaft Presentation 6 EnvironmentJuan Manuel OvalleNo ratings yet

- Reduce Home Energy Use and Recycling TipsDocument4 pagesReduce Home Energy Use and Recycling Tipsmin95No ratings yet

- Surrender Deed FormDocument2 pagesSurrender Deed FormADVOCATE SHIVAM GARGNo ratings yet

- Chemistry Sample Paper 2021-22Document16 pagesChemistry Sample Paper 2021-22sarthak MongaNo ratings yet

- Henry VII Student NotesDocument26 pagesHenry VII Student Notesapi-286559228No ratings yet

- Bias in TurnoutDocument2 pagesBias in TurnoutDardo CurtiNo ratings yet

- Helical Antennas: Circularly Polarized, High Gain and Simple to FabricateDocument17 pagesHelical Antennas: Circularly Polarized, High Gain and Simple to FabricatePrasanth KumarNo ratings yet

- Zeng 2020Document11 pagesZeng 2020Inácio RibeiroNo ratings yet

- First Time Login Guidelines in CRMDocument23 pagesFirst Time Login Guidelines in CRMSumeet KotakNo ratings yet

- Lifting Plan FormatDocument2 pagesLifting Plan FormatmdmuzafferazamNo ratings yet

- Forouzan MCQ in Error Detection and CorrectionDocument14 pagesForouzan MCQ in Error Detection and CorrectionFroyd WessNo ratings yet

- jvc_kd-av7000_kd-av7001_kd-av7005_kd-av7008_kv-mav7001_kv-mav7002-ma101-Document159 pagesjvc_kd-av7000_kd-av7001_kd-av7005_kd-av7008_kv-mav7001_kv-mav7002-ma101-strelectronicsNo ratings yet

- PAASCU Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesPAASCU Lesson PlanAnonymous On831wJKlsNo ratings yet

- HVDC PowerDocument70 pagesHVDC PowerHibba HareemNo ratings yet

- Chess Handbook For Parents and Coaches: Ronn MunstermanDocument29 pagesChess Handbook For Parents and Coaches: Ronn MunstermanZull Ise HishamNo ratings yet

- Adam Smith Abso Theory - PDF Swati AgarwalDocument3 pagesAdam Smith Abso Theory - PDF Swati AgarwalSagarNo ratings yet

- 486 Finance 17887 Final DraftDocument8 pages486 Finance 17887 Final DraftMary MoralesNo ratings yet

- Khandelwal Intern ReportDocument64 pagesKhandelwal Intern ReporttusgNo ratings yet

- The Gnomes of Zavandor VODocument8 pagesThe Gnomes of Zavandor VOElias GreemNo ratings yet

- Monetbil Payment Widget v2.1 enDocument7 pagesMonetbil Payment Widget v2.1 enDekassNo ratings yet

- 01.09 Create EA For Binary OptionsDocument11 pages01.09 Create EA For Binary OptionsEnrique BlancoNo ratings yet

- Polisomnografí A Dinamica No Dise.: Club de Revistas Julián David Cáceres O. OtorrinolaringologíaDocument25 pagesPolisomnografí A Dinamica No Dise.: Club de Revistas Julián David Cáceres O. OtorrinolaringologíaDavid CáceresNo ratings yet

- Vol 013Document470 pagesVol 013Ajay YadavNo ratings yet

- Senarai Syarikat Berdaftar MidesDocument6 pagesSenarai Syarikat Berdaftar Midesmohd zulhazreen bin mohd nasirNo ratings yet

- Algebra Extra Credit Worksheet - Rotations and TransformationsDocument8 pagesAlgebra Extra Credit Worksheet - Rotations and TransformationsGambit KingNo ratings yet