Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Clarinet Emb

Uploaded by

api-217908378Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Clarinet Emb

Uploaded by

api-217908378Copyright:

Available Formats

SPOTLIGHT ON WOODWINDS / LES BOIS DE PLUS PRS

The Clarinet Embouchure

Timothy Maloney

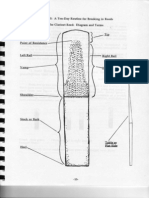

Single-Lip Embouchure The embouchure discussed in this article is the single-lip embouchure of the French school of clarinet playing, used by many clarinetists around the world. It is referred to in this way because only one lip is directly involved: the lower lip is turned back over the bottom teeth so that about half of the pink, eshy part of the lip forms a cushion for the reed to rest on. The top teeth should rest lightly on the mouthpiece about half an inch or so from the tip. Both lips should encircle the mouthpiece like a rubber band, supple and pliable, keeping all the air inside and chanelling it through the mouthpiece and into the clarinet. No air should leak from the corners of the mouth or form pockets in the cheeks or below the bottom lip. The corners of the mouth should be stretched back and upward, as if smiling, and the chin should be pointed downward toward the chest, stretching the skin below the bottom lip. These are the essential features of the French clarinet embouchure. There are other approaches to the single-lip clarinet embouchure, notably that of the German school of playing, where the smile element is absent. There is also a double-lip embouchure, briey discussed further below. At the very beginning, students should practice forming the correct embouchure by substituting the right index nger for the mouthpiece. Have them check themselves in a mirror, making sure they incorporate each of the elements outlined above, concentrating particularly on pointing the chin and pulling the corners of the mouth back and up. As a second step, have them blow into the mouthpiece (or mouthpiece-barrel combination), detached from the clarinet but with a moist reed on it, checking in the mirror as they do so. Using reeds no stronger than 1 or 2 for the earliest attempts should help the process. It is essential that students not let their embouchure collapse as the mouthpiece enters their mouth. This is a common problem with beginners. They should think in terms of setting the embouchure and inserting the mouthpiece into it, or bringing the mouthpiece/ clarinet to the embouchure rather than the embouchure to the mouthpiece/clarinet (by letting the embouchure lose its shape as the mouthpiece is inserted). To maintain concentration on the mouth, the rst note a student should attempt to play on the clarinet is an open G not too forcefully, to help keep the embouchure from collapsing. If all goes well and the embouchure shape is maintained, the student can proceed downward step by step with the left-hand thumb and ngers, playing through F, E, D, and C. This should be relatively uncomplicated, and the focus should continue to be on maintaining a good embouchure shape throughout the process. If the shape is lost or the embouchure collapses at any point, have the student begin again with the index nger, then with the mouthpiece-reed combination, and nally with the mouthpiece

attached to the clarinet. Make sure the reed is not contributing to any problems by being too hard, too dry, or incorrectly placed on the mouthpiece. Preparing the mouthpiece tenon with some cork grease ahead of time will facilitate the insertion/withdrawal of the mouthpiece or mouthpiece-barrel combination into/from the clarinet. Let me pause briey in this discussion to point out that I am a rm believer in holding separate introductory sessions for each instrumental group: i.e., clarinets alone, utes alone, trumpets alone, and so on. The attention to details and individual problems possible in segregated beginner instruction sessions cannot be replicated in classes where beginners on different instruments are all trying to make their rst sounds. I am also a proponent of having beginners play by ear before they attempt to read music, so as not to divert attention away from the embouchure and sound production too soon. Early in my career, I taught Grades 6-12 instrumental music for a few years, and the strongest beginner band I ever had happened the year the band books did not arrive until a few weeks after classes began. By that point, the beginners in question, playing mainly by ear, had far outstripped my previous beginner classes in their command of the fundamentals. The reasons were easy to gure out. Some basic rst tunes to be attempted by ear include the following, which can all be played in C Major on the clarinet using only the left-hand: Mary Had a Little Lamb, Twinkle, Twinkle, Lightly Row, Oh Susanna, and Fiddle-I-Dee. When tunes requiring only the left hand have been sufciently mastered with the embouchure intact, the right-hand ngerings of low B, B-at, A, and G can be introduced, and tunes such as these can be attempted: Alouette, The More We Get Together, Amazing Grace, Go Tell It On The Mountain, O Christmas Tree (all in C Major), and We Three Kings (in A minor). As students develop some prociency on the instrument and expand the range of notes they can play, the basic embouchure shape described above should remain unchanged no matter what kind of music is played: low or high, soft or loud, fast or slow, staccato or legato. The clarinet embouchure can be equated to a violinists grip on her bow: no matter how she plays, her hand grip never changes. For clarinetists, our grip is our embouchure, and our bow is the air we blow. What does change is the air speed: faster air for loud passages, slower for soft (just like the violin bow speed); more intensity in the air stream for the high register, less for the low but our embouchure always stays the same. With young clarinetists, this is rarely the case, so it is a goal for them to keep in mind and work towards, with periodic reminders from their teacher. Some embouchure Dos and Donts include the following: 1. Too much lower lip turned over the teeth will interfere with the free vibration of the reed, and can also cause discomfort or pain from insufcient cushion between the reed and the bottom teeth.

Vents canadiens Canadian Winds Fall / automne 2010 31

THE CLARINET EMBOUCHURE

2. Too little lower lip turned over the teeth can result in lack of control of the sound. 3. Biting or clamping down hard on the mouthpiece with the upper teeth may cause the teeth to loosen and move, and inicts enormous wear and tear on the mouthpiece. Tell-tale evidence of this is gouging of the mouthpiece by the upper front teeth. The upper teeth should simply rest on the mouthpiece. 4. Too much pressure from the lower teeth or lip can also prove painful, and sometimes interferes with the reeds ability to vibrate freely. Inexperienced clarinetists often resort to this type of biting to try to bring high notes up to pitch, instead of increasing the intensity of the air stream. One can test for this by gently pulling the instrument from students mouths while they are playing. This can be accomplished without causing any harm to the clarinetist or the reed. If a clarinet cannot easily be extracted from students mouths while playing, they are probably biting to at least some extent. Breathing deeply and increasing the diaphragm pressure should be stressed and practiced to counteract this problem. Reeds of sufcient strength are also a requirement to play high notes without resorting to biting or other bad habits. 5. Too much or too little mouthpiece in the mouth can affect the tone quality and control of the notes being played. While the size and shape of everyones mouth is different, it is possible for students to nd the right placement for themselves by doing a little experimenting. Once they nd the placement that gives them good control and tone quality, they need to keep it. 6. The jaw should not move when tonguing. It and the rest of the embouchure should remain stationary while the tip of the tongue moves forward and back inside the mouth, engaging and releasing the blade of the reed at its tip. 7. Over-blowing is bad for the embouchure and usually distorts the sound, causing the pitch to go at. It also causes the embouchure to collapse. Avoid it at all costs. 8. Students need to hold their clarinets rmly, not letting the instrument move or wobble in their mouths. The right thumb should not only support the clarinet, it should constantly push the instrument upward, keeping it rmly in the mouth. The lips can then do their job of encircling the mouthpiece and maintaining the correct shape and functions. 9. Weak reeds are incompatible with healthy embouchures. As beginners gain experience playing over the break and exploring the upper register, they should be encouraged to use stronger reeds, moving incrementally to #2, 2, and 3 as their embouchures gain strength and muscle-tone. Given the tessitura of rst-clarinet parts in typical band music, members of that section should normally be playing on no less than #2 reeds #3 if possible. However, sufcient preparation and incremental change are crucial, since attempting to play on a reed that is too strong for ones embouchure is a sure way to cause the embouchure to collapse. 10. Intermediate and advanced students should also be encouraged to have several reeds broken in and used in rotation at all times, rather than playing one reed to death. Rotating ones reed supply, and periodically introducing new reeds while phasing out older reeds (which weaken after much playing) helps keep the embouchure strong and exible. Playing on one reed to the exclusion of all others is very harmful to anyones embouchure. (For further information on clarinet reeds, see my article, A Tutorial on Single Reeds, in Canadian Winds/Vents canadiens, Vol. 1, No. 2, Spring 2003, pp. 18-23.) Double-Lip Embouchure Some clarinetists employ a double-lip embouchure, also cushioning their top teeth with the upper lip, as oboists do. In the nineteenth century, many more clarinetists played that way, especially the Italians, and it was the only kind of clarinet embouchure employed throughout Europe in much of the eighteenth century, when the clarinet mouthpiece was turned so that the reed was on top. Once it was discovered that stronger reeds (resulting in better tone and more volume) could be used by positioning the reed underneath, the double-lip embouchure was no longer a necessity for clarinetists. For general use, this embouchure has some drawbacks (e.g., a looser grip on the mouthpiece, which usually necessitates supporting the clarinet bell with ones leg or knee), and most of us do not employ it today. Some of the nest professional clarinetists have used it with great success, though, including the late Harold Wright, the former Principal Clarinet of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. A present-day practitioner of the doublelip embouchure is Richard Stoltzman, a touring soloist with many CDs to his credit (visit www.richardstoltzman.com). Most professional clarinetists today try to integrate the best feature of the double-lip embouchure into their single-lip embouchure: namely, the high arch in the soft palate (the soft tissue along the roof of the mouth back towards the throat). This can be accomplished by concentrating on an open throat, the smile shape of the lips, and constantly pointing the chin downward. The more the chin is pointed down and the skin there stretched, the greater the arch in the soft palate. One can also get the right feel by forming a double-lip embouchure on the mouthpiece and then gently withdrawing the top lip while concentrating on maintaining the arched palate. This is more a matter for advanced students to think about, not something that beginners need to worry about. For beginner and intermediate clarinetists, it is a good idea to play frequently in front of a mirror to check for collapsed embouchures and other bad habits (e.g., poor hand positions). All band rooms and practice rooms should be equipped with mirrors. Spotting and correcting problems and bad habits early is much easier than trying to undo habits that have been reinforced over a longer period of time. It is also highly desirable for band directors to engage the services of a local professional clarinetist or an advanced university student to keep your clarinetists on their toes through clinics, workshops, sectional rehearsals, and clarinet-choir activities. Such attention

32 Fall / automne 2010 Canadian Winds Vents canadiens

THE CLARINET EMBOUCHURE

to an instrumental group that is often the largest in the band can pay abundant long-term dividends. Further information and diagrams about the clarinet embouchure can be found at Web sites such as the following: www.kjos.com/band/band_news/band_news_emb2.html www.keynotesmagazine.com/article/?uid=162 en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Clarinet/Clarinet_Basics/Tone/ Embouchure www.clarinet-now.com/clarinet-embouchure.html

Timothy Maloney

has played clarinet in professional orchestras and chamber ensembles in the U.S. and Canada, and has taught clarinet at the college/university level in both countries. His playing can be heard on commercial CDs issued by the CBC, CanSona, and Albany labels. Among his clarinet teachers were Harold Wright, Stanley Hasty, and Guy Deplus.

Est. 1980

Attend Canadas Largest Music Festival

ld Go for the Go BC in Richmondt,2011

es host of MusicF

Richmond - May 2011

Showcase Concerts Workshops Masterclasses Scholarships

Celebrating 30 years creating memories that last...

reg. #2392471

Appointed agent for MusicFest Canada

Contact Tasha Shields Exeter Office ~ tashas@ettravel.com Marcie Ellison Outerbridge Vancouver office ~ marcieo@ettravel.com

311 Main St., Exeter, Ontario phone: 519 235-2000 1-800-265-7024

www.musictours-festivals.com email: group@ettravel.com

116 - 255 West 1st St., North Vancouver B.C. phone: 604 983-2470 1-866-983-2470

Vents canadiens Canadian Winds Fall / automne 2010 33

Copyright of Canadian Winds / Vents Canadiens is the property of Canadian Band Association and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- First Embouchure Column For ClarinetDocument9 pagesFirst Embouchure Column For ClarinetMohamed F. Zanaty100% (1)

- Problems & Solutions Regarding Clarinet EmbouchureDocument5 pagesProblems & Solutions Regarding Clarinet Embouchureallison_gerber100% (1)

- Essentials of Clarinet Pedagogy The First Three Years The Embouchure and Tone ProductionDocument23 pagesEssentials of Clarinet Pedagogy The First Three Years The Embouchure and Tone ProductionFilipe Silva MoreiraNo ratings yet

- Clarinet Howard KlugDocument6 pagesClarinet Howard KlugGloria Wan100% (1)

- 04 Day One Handout - Clarinet FinalDocument7 pages04 Day One Handout - Clarinet Finalapi-551389172No ratings yet

- Clarinet TechniqueDocument9 pagesClarinet TechniquemparunakNo ratings yet

- Clarinet Tips OutlineDocument6 pagesClarinet Tips Outlineapi-551389172No ratings yet

- Elementary Clarinet Pedagogy: A Sound ApproachDocument12 pagesElementary Clarinet Pedagogy: A Sound Approachdoug_monroeNo ratings yet

- Alternate Fingering Chart For Boehm-System Clarinet: Chalumeau Register: E TobDocument27 pagesAlternate Fingering Chart For Boehm-System Clarinet: Chalumeau Register: E TobsssorinfrNo ratings yet

- Fit in 15 Minutes: Warm-ups and Essential Exercises for ClarinetFrom EverandFit in 15 Minutes: Warm-ups and Essential Exercises for ClarinetRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Robert MarcellusDocument6 pagesRobert MarcellusBasilis Sisyphus100% (1)

- Army Band Clarinet TechniquesDocument18 pagesArmy Band Clarinet TechniquesRichard Li100% (1)

- Clarinet HandbookDocument4 pagesClarinet Handbookmasemusic123No ratings yet

- Adjusting Clarinet ReedsDocument15 pagesAdjusting Clarinet Reedsapi-201119152100% (1)

- Basic Clarinet AcousticsDocument17 pagesBasic Clarinet Acousticsprofessoraloha100% (8)

- The Pedagogy Corner: Studying Articulation in DepthDocument5 pagesThe Pedagogy Corner: Studying Articulation in DepthPatercomunitas100% (1)

- Clarinet Tuning ChartDocument1 pageClarinet Tuning ChartDaniel MokNo ratings yet

- Saxophone and Clarinet Fundamentals PDFDocument31 pagesSaxophone and Clarinet Fundamentals PDFAlberto Gomez100% (1)

- Backun Alternate Fingerings: Volume 2, Upper RegisterDocument20 pagesBackun Alternate Fingerings: Volume 2, Upper RegisterRoberto RossettiNo ratings yet

- Polatschek 24 StudiesDocument18 pagesPolatschek 24 Studiesclaridclarinet100% (1)

- Clarinetists Compendium BonadeDocument18 pagesClarinetists Compendium Bonadefarfex100% (1)

- The Clarinet Embouchure - Carmine CampioneDocument5 pagesThe Clarinet Embouchure - Carmine Campioneomnimusico100% (3)

- Clarinet AcousticsDocument15 pagesClarinet Acousticsdoug_monroe100% (2)

- Advanced Intonation Technique For ClarinetsDocument54 pagesAdvanced Intonation Technique For ClarinetsStefano Cinnirella100% (1)

- Clarinet Harmonic SeriesDocument3 pagesClarinet Harmonic SeriesAndreea Poetelea100% (1)

- Backun Alternate Fingerings: Volume 1, Throat TonesDocument14 pagesBackun Alternate Fingerings: Volume 1, Throat TonespaubarrinaNo ratings yet

- Making Clarinet ReedsDocument21 pagesMaking Clarinet Reedsprofessoraloha100% (12)

- Clarinet Technique PacketDocument24 pagesClarinet Technique PacketEmmett O'Leary100% (7)

- Tuning and Voicing The Clarinet PDFDocument10 pagesTuning and Voicing The Clarinet PDFLeko Mladenovski100% (1)

- Scales Clarinet Complete GuideDocument6 pagesScales Clarinet Complete Guidemorta8ka8ionait80% (1)

- Clarinet Warm-Ups (Materials For The Contemporary Clarinetist)Document12 pagesClarinet Warm-Ups (Materials For The Contemporary Clarinetist)Travis Boudreau100% (1)

- DAY 25 B Minor 1Document12 pagesDAY 25 B Minor 1Lundrim RexhaNo ratings yet

- Clar Essentiel A NGDocument24 pagesClar Essentiel A NGmacronortepauloNo ratings yet

- Interview - Robert Marcellus PDFDocument6 pagesInterview - Robert Marcellus PDFclarinmala100% (1)

- Epígeno No.2 For Bass ClarinetDocument4 pagesEpígeno No.2 For Bass ClarinetjailtondeoliveiraNo ratings yet

- Weber Concertino Rev. Bonade-HiteDocument4 pagesWeber Concertino Rev. Bonade-HiteZackary WebsterNo ratings yet

- Horovitz ClarinetDocument1 pageHorovitz ClarinetMarco ApazaNo ratings yet

- CLARINETE - GUIA - Leblanc (AV4013) - Apostila Conn-Selmer (Em Inglê S)Document35 pagesCLARINETE - GUIA - Leblanc (AV4013) - Apostila Conn-Selmer (Em Inglê S)Juan Carlos GiraldoNo ratings yet

- Clarinet Alternate Fingering SDocument2 pagesClarinet Alternate Fingering Sints27No ratings yet

- Clarinet Fundamentals 2: Systematic Fingering CourseFrom EverandClarinet Fundamentals 2: Systematic Fingering CourseRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Clarinet - Altissimo Register - Trill Fingering Chart For Boehm-System Clarinet - The Woodwind Fingering GuideDocument4 pagesClarinet - Altissimo Register - Trill Fingering Chart For Boehm-System Clarinet - The Woodwind Fingering GuideJim GailloretoNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Tonguing and Blowing Actions During Clarinet PerformanceDocument12 pagesAnalysis of Tonguing and Blowing Actions During Clarinet PerformancePatercomunitasNo ratings yet

- Etheridge, David - A Practical Approaqch To The Clarinet - AdvancedDocument86 pagesEtheridge, David - A Practical Approaqch To The Clarinet - AdvancedPedro Silva100% (6)

- Clarinet Master Class PDFDocument4 pagesClarinet Master Class PDFRogério ConceiçãoNo ratings yet

- Clarinet Reed AdjustmentDocument6 pagesClarinet Reed AdjustmentJuan Sebastian Romero Albornoz100% (2)

- Reed Adjustment PDFDocument6 pagesReed Adjustment PDFstefanaxe75% (4)

- (Clarinet - Institute) Bach For Solo Clarinet PDFDocument30 pages(Clarinet - Institute) Bach For Solo Clarinet PDFVeronica NoseiNo ratings yet

- Clarinet Altissimo RegisterDocument7 pagesClarinet Altissimo RegisterJuan Sebastian Romero AlbornozNo ratings yet

- Bass Clarinet Basics PDFDocument12 pagesBass Clarinet Basics PDFAlberto Hernández Gómez100% (1)

- W251R Clarinets PDFDocument12 pagesW251R Clarinets PDFKaren AparicioNo ratings yet

- The Developing Clarinet PlayerDocument157 pagesThe Developing Clarinet PlayerclarinmalaNo ratings yet

- (Cliqueapostilas - Com.br) Apostila de Clarinete 12Document55 pages(Cliqueapostilas - Com.br) Apostila de Clarinete 12Ileusis LunaNo ratings yet

- Clarinet Fundamentals Complete - FingeringsDocument29 pagesClarinet Fundamentals Complete - FingeringsEmmett O'Leary93% (30)

- Clarinet CoursepackDocument117 pagesClarinet Coursepackmbean_7100% (14)

- Flute Articles Worth KnowingDocument1 pageFlute Articles Worth Knowingapi-217908378No ratings yet

- Bassoon BasicsDocument4 pagesBassoon Basicsapi-217908378No ratings yet

- Flute Beginning ExercisesDocument4 pagesFlute Beginning Exercisesapi-217908378No ratings yet

- Flute GuideDocument7 pagesFlute GuideJan EggermontNo ratings yet

- Flute Balance PointsDocument1 pageFlute Balance Pointsapi-217908378No ratings yet

- Oboe BasicsDocument5 pagesOboe Basicsapi-199307272No ratings yet

- Reed Players Doubling FluteDocument1 pageReed Players Doubling Fluteapi-217908378No ratings yet

- Clarinet Mainte 1-1Document1 pageClarinet Mainte 1-1api-236899237No ratings yet

- Flute MainteDocument1 pageFlute Mainteapi-201119152No ratings yet

- Grade Woodwind StudentsDocument8 pagesGrade Woodwind Studentsapi-217908378No ratings yet

- Your Very First Clarinet Exercies 1Document1 pageYour Very First Clarinet Exercies 1api-217908378No ratings yet

- BeginningbassoonistDocument9 pagesBeginningbassoonistapi-201119152No ratings yet

- Clarinet EquipmentDocument2 pagesClarinet Equipmentapi-236899237No ratings yet

- UpfrontDocument4 pagesUpfrontapi-217908378No ratings yet

- Img 021Document1 pageImg 021api-217908378No ratings yet

- Woodwind VibratoDocument6 pagesWoodwind Vibratoapi-217908378No ratings yet

- The Effects of Syllabic Articulation Instruction OnwoodwindDocument6 pagesThe Effects of Syllabic Articulation Instruction Onwoodwindapi-217908378No ratings yet

- Keys To Better Saxophone ArticulationDocument2 pagesKeys To Better Saxophone Articulationapi-217908378No ratings yet

- Introducing Jazz Concepts To Young PlayersDocument2 pagesIntroducing Jazz Concepts To Young Playersapi-217908378No ratings yet

- Tuning The Woodwind SectionDocument2 pagesTuning The Woodwind Sectionapi-217908378No ratings yet

- Img 020Document2 pagesImg 020api-217908378No ratings yet

- Img 019Document4 pagesImg 019api-217908378No ratings yet

- Embouchure StrategiesDocument2 pagesEmbouchure Strategiesapi-217908378No ratings yet

- Revisiting Teaching Strategies For WoodwindsDocument12 pagesRevisiting Teaching Strategies For Woodwindsapi-217908378No ratings yet

- Helpful Hints For Teaching BassoonDocument2 pagesHelpful Hints For Teaching Bassoonapi-217908378No ratings yet

- Img017 1Document3 pagesImg017 1api-217908378No ratings yet

- Standard OboerepertoireDocument4 pagesStandard Oboerepertoireapi-217908378100% (1)

- Saxophone PedagogyDocument2 pagesSaxophone Pedagogyapi-217908378No ratings yet

- Img 018Document3 pagesImg 018api-217908378No ratings yet

- Saxophone Performance 1Document5 pagesSaxophone Performance 1api-217908378No ratings yet

- Materi Bhs IngDocument6 pagesMateri Bhs IngEllyaFitrianiNo ratings yet

- Soal Olimpiade Bhs Inggris Mts 2013Document3 pagesSoal Olimpiade Bhs Inggris Mts 2013Khudori94% (18)

- ACE English Malta - Student Enrolment Form - 2017 PDFDocument6 pagesACE English Malta - Student Enrolment Form - 2017 PDFTatiana HoyosNo ratings yet

- Multiple Intelligences: Ms - Ed. Ana Aguirre Jiménez Ms - Ed. Margot Solis LarraínDocument26 pagesMultiple Intelligences: Ms - Ed. Ana Aguirre Jiménez Ms - Ed. Margot Solis LarraínNoemí Margot Solis LarraínNo ratings yet

- Report JsaDocument14 pagesReport JsaNur Izzati SebriNo ratings yet

- Students NeedsDocument2 pagesStudents NeedsJonnifer LagardeNo ratings yet

- Teachers Name: Jessica D. Cagulangan Sex: F Subj Taught: Math Grade/Yr Level: G-9 & 10Document2 pagesTeachers Name: Jessica D. Cagulangan Sex: F Subj Taught: Math Grade/Yr Level: G-9 & 10marie michelleNo ratings yet

- How Motivation Affects Learning and Behavior - ArticleDocument4 pagesHow Motivation Affects Learning and Behavior - ArticleZiminNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Learning DisabilitiesDocument29 pagesPresentation On Learning Disabilitiestricia0910100% (4)

- Stootsd UnitplanreflectionDocument3 pagesStootsd Unitplanreflectionapi-317044149No ratings yet

- Teaching and Learning in The Digital Age Course Syllabus Angela Brown Fall 2013Document5 pagesTeaching and Learning in The Digital Age Course Syllabus Angela Brown Fall 2013api-233750759No ratings yet

- Teacher Expectation Student PerformanceDocument31 pagesTeacher Expectation Student PerformanceMark AndrewNo ratings yet

- 7th Grade Science Class Behavior ContractDocument1 page7th Grade Science Class Behavior Contractapi-343241309No ratings yet

- Affirmative Online Education. EditDocument5 pagesAffirmative Online Education. EdityellowishmustardNo ratings yet

- Work Immersion at The Municipal Treasurer Pt2Document27 pagesWork Immersion at The Municipal Treasurer Pt2Philip Andrey67% (3)

- WHO MNH PSF 93.7A Rev.2 PDFDocument53 pagesWHO MNH PSF 93.7A Rev.2 PDFThe Lost ChefNo ratings yet

- The College of New Jersey Hosts Its First New Jersey Model United Nations ConferenceDocument16 pagesThe College of New Jersey Hosts Its First New Jersey Model United Nations ConferenceHenggao CaiNo ratings yet

- LEARNING ENVI Joanne ZarateDocument46 pagesLEARNING ENVI Joanne ZaratesherwinNo ratings yet

- Gen Math GAS Daily Lesson LogDocument5 pagesGen Math GAS Daily Lesson Logjun del rosario100% (1)

- Mercury Sydney CatalgoDocument25 pagesMercury Sydney CatalgoIntercambio Combr ErickNo ratings yet

- TeodoraUdrescu CV EuropassDocument3 pagesTeodoraUdrescu CV EuropassTeodora UdrescuNo ratings yet

- Attitudes of Students and Teachers Towards Use of Computer Technology in Geography EducationDocument2 pagesAttitudes of Students and Teachers Towards Use of Computer Technology in Geography EducationUcing Garong HideungNo ratings yet

- 8ways - HomeDocument6 pages8ways - HomemalcroweNo ratings yet

- Philosophical and Psychological-FoundationsDocument15 pagesPhilosophical and Psychological-FoundationsJanice JarsulaNo ratings yet

- TechnologyDocument4 pagesTechnologyapi-297909206No ratings yet

- IPM Mega Final 2019Document1 pageIPM Mega Final 2019Kvn Sneh50% (2)

- Lesson ContractDocument2 pagesLesson Contractapi-383968408No ratings yet

- Teacher's Guide - Year 6 Basic Education PDFDocument92 pagesTeacher's Guide - Year 6 Basic Education PDFmejmak100% (3)

- 21.05.2014 - Teaching Quality and Performance Among Experienced Teachers in MalaysiaDocument7 pages21.05.2014 - Teaching Quality and Performance Among Experienced Teachers in MalaysiaAmysophiani Ha-Eun AdeniNo ratings yet

- JK SK Retell Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesJK SK Retell Lesson Planapi-277472970No ratings yet