Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The syllable in generative phonology

Uploaded by

Ahmed S. MubarakOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The syllable in generative phonology

Uploaded by

Ahmed S. MubarakCopyright:

Available Formats

The syllable in generative phonology The 1950s and 1960s saw a new approach to language study: generative linguistics,

associated primarily with Noam Chomsky and his contemporaries. This ultimately became the current 'mainstream' of Western linguistic research, leading to theories of both syntax and phonology. Within generative theory, prosodic structure (levels of phonological information, from the segment up to the syllable and the intonation pattern imposed on an utterance) is formed according to the principles of 'Universal Grammar' (UG), which underlie all languages.[14] A speaker of a language possesses some kind of faculty which explicitly sets out what kinds of syllables, patterns of segments and other levels of phonological information are possible, while ruling out those which are not. This, crucially, unfolds in neurologically typical children without instruction, and little influence from the environment around them. For example, children typically produce syllables of consonantvowel (CV) sequences from their earliest productions. However, this presence of the syllable in first language acquisition did not immediately lead to its recognition as a crucial unit of phonological theory. The syllable as a segmental rule By the time of Chomsky and Halles Sound Pattern of English[15] (henceforth 'SPE'), the syllable had been abandoned as a formal phonological unit.[16] In SPE the syllable was not explicitly referred to except as the segmental rather than prosodic feature [ syllabic], attached to vowels and syllabic consonants.[17] However, though there was nothing in SPEbetween the word and the segment, one could infer the existence of the syllable from rules which seemed to take the syllable as their domain of application.[18] For example, a rule inSPE which seems to apply both to word-edges and adjacent consonants becomes suddenly transparent if it is assumed that it activates at the edge of the syllable.[19] An example of this is glottalisation in English, where the /t/ in but, butter and bottle may be glottalised by many speakers. Assuming this occurs at the right edge of the syllable covers what might otherwise be regarded as three separate rules. In the 1970s, the syllable was reintroduced to generative linguistics as a rule inserting boundaries between segments.[20] The syllable had returned as a formal linguistic reality, but remained tied to the segmental level. The syllable as a suprasegmental By the 1980s, the theory that the syllable was confined to the segmental tier - i.e. that certain segments such as vowels could be inherently syllabic - had been eroded. The syllable came to be seen as a separate 'suprasegmental' unit of organisation, i.e. segments could be grouped inside a syllable but not form the structure of the syllable itself.[21] While one avenue of inquiry questioned whether the syllable was a true linguistic universal at all,[22] the majority of phonologists found the syllable invaluable in describing and predicting data. Assuming the syllable to both exist and be a suprasegmental unit allowed for a more productive description of permissible segmental ordering.[23] Challenges to the 'classic' model

Underlyingly, monosyllabic words with a final consonant actually consist of two syllables in government phonology. The traditional model of a syllable as onset, nucleus and coda united in one unit has been challenged in various ways, particularly since the 1990s. Some approaches assume the 'classic' model but modify it; for example, by linking initial and final consonants directly to the syllable itself rather than subsuming them under the intermediate onset and coda constituents.[24] In this version, the syllable consists of a nucleus and optional final consonants within the rhyme, with any pre-nucleic consonants on the same level as the rhyme. The theory of government phonology (GP) is still more radical[25]. This view denies that syllables exist as organising units in their own right; appealing to an 'onset-rhyme constituent' is enough. In other words, phonological rules that supposedly apply to syllables can be better-described as applying to onsets, rhymes or both. Furthermore, final consonants are analysed not as part of the rhyme and/or coda, but as onsets - of 'covert' final syllables. Compare the GP approach to syllabifying the words 'cat' with the traditional model (right).

Some words that appear to differ in number of syllables are actually the same under the surface in government phonology. GP does not completely abolish rhymal consonants: in cases where a sequence of final consonants could not form a normal onset - such as in hand, where *[nd-] could not begin an English syllable - the consonant cluster is broken up as it would be if the two consonants occurred in different syllables: in panda the [n] and [d] occupy separate syllables, so this must also apply to final [-nd] sequences. Note that this means there is no prosodic difference between hand and handy; the addition of -y requires only that the vowel be 'plugged' into the existing syllable structure, rather than requiring a resyllabification rule to produce a new structure. The cost of extra 'covert' structure of phonetically unrealised syllables is met through not having to invoke rules of syllabification when an ending is affixed. This means, of course, that the underlying syllable structure may contrast sharply with speakers' intuitions about how many syllables a word has. Footnotes 1. All languages require onsets to be the initial constituent of the syllable; this is regardless of whether the language is written left to right, right to left or top to bottom. 2. Spoken in Nepal. 3. Although German has many words that begin with a vowel, phonetically a glottal stop is inserted to comply with this obligatory onset rule, except in cases where another consonant is resyllabified to occupy another's onset position as in, hab ich 'have I'. 4. In some models, all varieties of Chinese are considered to have obligatory onsets; see Duanmu (2007). 5. The spelling of button misleadingly implies that for most speakers there are two vowels in the word. 6. Languages allow more codas word-internally than word-finally. Both Japanese and Italian allow a full range of consonants inside the word, e.g. Italianditta 'office' and Japanese datte 'even (if)', though in the latter case they must be part of a long consonant (a geminate). Italian word-final codas are restricted to grammatical function words such as nel 'in the' and loanwords. 7. Some accounts place [s] outside the onset in words such as spread, because it syllabifies differently to 'true' onset consonants; cf. aspect and appraisal. 8. Pike & Pike (1947); Hockett (1955: 150-151). 9. Hockett (1958: 64). 10. Stetson (1951), as reported in Bell & Hooper (1978: 18).

11. Fujimura & Erickson (1997: 99). 12. Laver (1994: 114). 13. A rule which is not necessitated by the facts of phonetics is not "phonetically natural" (Bell & Hooper, 1978: 7). 14. Chomsky (1965). 15. Chomsky & Halle (1968). 16. Kohler (1966). 17. Bell and Hooper (1978: 5). 18. Fischer-Jrgensen (1975: 207); van der Hulst and Ritter (1999: 19). 19. Blevins (1995: 209). 20. Hooper (1972). 21. Selkirk (1984a: 22). 22. Hyman (1983). 23. Selkirk (1984b). 24. Blevins (1995: 216). 25. van der Hulst & Ritter 1999

You might also like

- Jenjo Noun Phrase StructureDocument14 pagesJenjo Noun Phrase StructureSamuel Ekpo100% (1)

- Phonology Homework 3Document8 pagesPhonology Homework 3api-279621217No ratings yet

- Traditional GrammarDocument4 pagesTraditional GrammarAsha MathewNo ratings yet

- Phonetics and Phonology Are The Two Fields Dedicated To The Study of Human Speech Sounds and Sound StructuresDocument11 pagesPhonetics and Phonology Are The Two Fields Dedicated To The Study of Human Speech Sounds and Sound StructuresKisan SinghNo ratings yet

- Functions of Syllables in English LanguageDocument3 pagesFunctions of Syllables in English LanguagePatricia Baldonedo100% (2)

- Comparative Study of Passive VoiceDocument6 pagesComparative Study of Passive VoiceWildan Fakhri100% (1)

- Are Languages Shaped by Culture or CognitionDocument15 pagesAre Languages Shaped by Culture or Cognitioniman22423156No ratings yet

- Sound Assimilation in English and Arabic A Contrastive Study PDFDocument12 pagesSound Assimilation in English and Arabic A Contrastive Study PDFTaha TmaNo ratings yet

- Psycholinguistics - Language ProcessingDocument42 pagesPsycholinguistics - Language ProcessingRakhshanda FawadNo ratings yet

- Polysemy and HomonymyDocument4 pagesPolysemy and Homonymynero daunaxilNo ratings yet

- Reiteration and CollocationDocument3 pagesReiteration and CollocationRoney Santos GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- Universitas Sumatera UtaraDocument13 pagesUniversitas Sumatera Utarahety hidayahNo ratings yet

- General Principles of Transformational Grammar But Have Challenged ChomskyDocument36 pagesGeneral Principles of Transformational Grammar But Have Challenged ChomskyMarilyn Honorio Daganta HerederoNo ratings yet

- Study Guide PDFDocument4 pagesStudy Guide PDFRobert Icalla BumacasNo ratings yet

- Underlying Representation of Generative Phonology and Indonesian PrefixesDocument50 pagesUnderlying Representation of Generative Phonology and Indonesian PrefixesJudith Mara AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Definition of GrammarDocument3 pagesDefinition of GrammarBishnu Pada Roy0% (1)

- Case GrammarDocument13 pagesCase GrammarSanettely0% (1)

- 6-Naturalness and StrengthDocument9 pages6-Naturalness and StrengthMeray HaddadNo ratings yet

- Saussure's Structural LinguisticsDocument10 pagesSaussure's Structural LinguisticsHerpert ApthercerNo ratings yet

- Noam-chomsky-The Cartography of Syntactic StructuresDocument17 pagesNoam-chomsky-The Cartography of Syntactic StructuresnanokoolNo ratings yet

- ElisionDocument4 pagesElisionTahar MeklaNo ratings yet

- Basic Tenets of Structural LinguisticsDocument6 pagesBasic Tenets of Structural LinguisticsAlan LibertNo ratings yet

- 5-Morphological Study of Verb Anglicisms in Spanish Computer Language PDFDocument5 pages5-Morphological Study of Verb Anglicisms in Spanish Computer Language PDFAnna84_84100% (1)

- "PRAGMATIC" by George Yule: Book ReviewDocument20 pages"PRAGMATIC" by George Yule: Book ReviewAmira BenNo ratings yet

- BIAK Noun MorphologyDocument5 pagesBIAK Noun MorphologyKrystel BalloNo ratings yet

- Final Exam LinguisticsDocument5 pagesFinal Exam Linguisticsdomonique tameronNo ratings yet

- Minimalist Inquiries: The Framework Chapter 3Document53 pagesMinimalist Inquiries: The Framework Chapter 3Monica Frias ChavesNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1. Lexicology As A Level of Linguistic AnalysisDocument9 pagesLecture 1. Lexicology As A Level of Linguistic AnalysisАннаNo ratings yet

- 0715 CB 035Document74 pages0715 CB 035RAyn FrAqaNo ratings yet

- Vowelizing English Consonant Clusters With Arabic Vowel Points Harakaat-Does It Help-July 2014Document20 pagesVowelizing English Consonant Clusters With Arabic Vowel Points Harakaat-Does It Help-July 2014aamir.saeed100% (1)

- Particles and Prepositions in EnglishDocument4 pagesParticles and Prepositions in EnglishAndra MihaiNo ratings yet

- Learn about the Hehe language spoken in TanzaniaDocument2 pagesLearn about the Hehe language spoken in TanzaniaAhmad EgiNo ratings yet

- Critical Review About The Differences of The Linguistic Mood Between Arabic and English LanguagesDocument6 pagesCritical Review About The Differences of The Linguistic Mood Between Arabic and English LanguagesJOURNAL OF ADVANCES IN LINGUISTICSNo ratings yet

- Articulation of Speech SoundsDocument6 pagesArticulation of Speech SoundsDian Hadi NurrohimNo ratings yet

- How Aspect Figures in Argument RealizationDocument15 pagesHow Aspect Figures in Argument RealizationDar Rotem100% (1)

- On Case Grammar, John AndersonDocument5 pagesOn Case Grammar, John AndersonMarcelo SilveiraNo ratings yet

- 1.concept of LanguageDocument19 pages1.concept of LanguageIstiqomah BonNo ratings yet

- How Language Changes: Group Name: Anggi Noviyanti: Ardiansyah: Dwi Prihartono: Indah Sari Manurung: Rikha MirantikaDocument15 pagesHow Language Changes: Group Name: Anggi Noviyanti: Ardiansyah: Dwi Prihartono: Indah Sari Manurung: Rikha MirantikaAnggi NoviyantiNo ratings yet

- Aula 1 - Morphemes and AllomorphsDocument13 pagesAula 1 - Morphemes and AllomorphsJose UchôaNo ratings yet

- How Modern English Is Different From Old EnglishDocument3 pagesHow Modern English Is Different From Old EnglishSuryajeeva Sures100% (1)

- Voice Quality - EslingDocument5 pagesVoice Quality - EslingFelipe TabaresNo ratings yet

- Weak Forms SummaryDocument2 pagesWeak Forms SummaryLucia100% (1)

- Phrase Structure Rules: Grammar GuideDocument1 pagePhrase Structure Rules: Grammar GuidefreklesNo ratings yet

- Tugas Uas PhonologyDocument86 pagesTugas Uas PhonologySofi Mina NurrohmanNo ratings yet

- Morphology - Study of Internal Structure of Words. It Studies The Way in Which WordsDocument6 pagesMorphology - Study of Internal Structure of Words. It Studies The Way in Which WordsKai KokoroNo ratings yet

- Words as building blocks of languageDocument5 pagesWords as building blocks of languageNur Al-AsimaNo ratings yet

- Morphology Introduction: Generative and ConceptsDocument17 pagesMorphology Introduction: Generative and Conceptsmocanu paulaNo ratings yet

- Transformational GrammarDocument1 pageTransformational GrammarBrendon JikalNo ratings yet

- Key Words: Lexical Ambiguity, Polysemy, HomonymyDocument5 pagesKey Words: Lexical Ambiguity, Polysemy, HomonymyDung Nguyễn HoàngNo ratings yet

- Phoneme PDFDocument26 pagesPhoneme PDFHusseinNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Grammar 5Document35 pagesTheoretical Grammar 5Айым МухтарбековаNo ratings yet

- Semantics and Pragmatics Group ProjectDocument31 pagesSemantics and Pragmatics Group ProjectNabilah YusofNo ratings yet

- Parts of Speech GuideDocument16 pagesParts of Speech GuideToledo, Denise Klaire M.100% (1)

- Lecture - 10. Phonetics LectureDocument78 pagesLecture - 10. Phonetics LectureMd Abu Kawser SajibNo ratings yet

- Deep StructureDocument9 pagesDeep StructureLoreinNo ratings yet

- Updated English LexicologyDocument179 pagesUpdated English LexicologyAziza QutbiddinovaNo ratings yet

- Connected SpeechDocument4 pagesConnected SpeechMaría CarolinaNo ratings yet

- 11 The Phoneme: B. Elan DresherDocument26 pages11 The Phoneme: B. Elan DresherLaura CavalcantiNo ratings yet

- Sociolinguistic VariablesDocument3 pagesSociolinguistic VariablesAhmed S. Mubarak100% (1)

- Free vs Bound Morphemes: Understanding Their DistinctionDocument2 pagesFree vs Bound Morphemes: Understanding Their DistinctionAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- The Nature of IronyDocument1 pageThe Nature of IronyAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- The Notion of ContextDocument4 pagesThe Notion of ContextAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- Toward The Optimal LexiconDocument13 pagesToward The Optimal LexiconAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- Derivational and Inflectional MorphemesDocument3 pagesDerivational and Inflectional MorphemesAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- Linguistics Lecture Notes - Edward StablerDocument152 pagesLinguistics Lecture Notes - Edward StablerLennie LyNo ratings yet

- Negated Antonyms and Approximative Number Words: Two Applications of Bidirectional Optimality TheoryDocument31 pagesNegated Antonyms and Approximative Number Words: Two Applications of Bidirectional Optimality TheoryAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence of Masculine Expressions in EnglishDocument1 pageThe Prevalence of Masculine Expressions in EnglishAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- Group BDocument6 pagesGroup BAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- Journal of Humanistic and Social StudiesDocument166 pagesJournal of Humanistic and Social StudiesAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- How The Brain Organizes LanguageDocument2 pagesHow The Brain Organizes LanguageKhawla AdnanNo ratings yet

- Proposal 2Document6 pagesProposal 2Ahmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- Communication Between Men and Women in The Context of The Christian CommunityDocument16 pagesCommunication Between Men and Women in The Context of The Christian CommunityAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- SociolinguisticsDocument6 pagesSociolinguisticsAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- PHD SyllabiDocument2 pagesPHD SyllabiAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- Proposal 2Document6 pagesProposal 2Ahmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- The Context of Situation Is TheDocument2 pagesThe Context of Situation Is TheAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Teaching Culture in EFL ClassroomsDocument7 pagesThe Importance of Teaching Culture in EFL ClassroomsAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- Frame, SchemaDocument19 pagesFrame, SchemaAhmed S. Mubarak100% (1)

- 2010 Pragmatic Competence The Case of HedgingDocument20 pages2010 Pragmatic Competence The Case of HedgingAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- The Acquisition of Gambits in IndonesiaDocument4 pagesThe Acquisition of Gambits in IndonesiaAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- Etymology of GambitDocument1 pageEtymology of GambitAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- Hedges 1Document17 pagesHedges 1Ahmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- Utterance ProductionDocument6 pagesUtterance ProductionAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- GLOSSARYDocument1 pageGLOSSARYKhawla AdnanNo ratings yet

- 2010 Pragmatic Competence The Case of HedgingDocument20 pages2010 Pragmatic Competence The Case of HedgingAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- Framework For Analysis of Mitigation in CourtsDocument45 pagesFramework For Analysis of Mitigation in CourtsAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- PHD SyllabiDocument2 pagesPHD SyllabiAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- HBR - Critical Thinking - Learning The ArtDocument5 pagesHBR - Critical Thinking - Learning The ArtVishnu Kanth100% (1)

- A. J. Ayer - The Elimination of MetaphysicsDocument1 pageA. J. Ayer - The Elimination of MetaphysicsSyed Zafar ImamNo ratings yet

- Jan de Vos - The Metamorphoses of The Brain - Neurologisation and Its DiscontentsDocument256 pagesJan de Vos - The Metamorphoses of The Brain - Neurologisation and Its DiscontentsMariana RivasNo ratings yet

- Survival in Southern SudanDocument14 pagesSurvival in Southern Sudanapi-242438369No ratings yet

- Kid Friendly Informational RubricDocument1 pageKid Friendly Informational RubricmrscroakNo ratings yet

- RPH Year 2 LinusDocument37 pagesRPH Year 2 Linuspuancaca100% (1)

- Wong Et Al. - Psychosocial Development of 5-Year-Old Children With Hearing LossDocument13 pagesWong Et Al. - Psychosocial Development of 5-Year-Old Children With Hearing LossPablo VasquezNo ratings yet

- Approximate Scheme of Overall StylisticDocument1 pageApproximate Scheme of Overall StylisticДиана АлексеенкоNo ratings yet

- Inclusive ClassroomDocument7 pagesInclusive Classroomsumble ssNo ratings yet

- Understanding the Learner's Development and EnvironmentDocument8 pagesUnderstanding the Learner's Development and EnvironmentBapa LoloNo ratings yet

- Research Variables GuideDocument2 pagesResearch Variables GuideBaste BaluyotNo ratings yet

- Assignment On "Qualities of Good Research"Document4 pagesAssignment On "Qualities of Good Research"Deepanka BoraNo ratings yet

- SAP PM Codigos TDocument7 pagesSAP PM Codigos Teedee3No ratings yet

- Employee Attitude SurveyDocument5 pagesEmployee Attitude SurveyCleofyjenn Cruiz QuibanNo ratings yet

- 06 Learning SystemsDocument82 pages06 Learning Systemssanthi sNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 HandbookDistanceLearningDocument15 pagesChapter 4 HandbookDistanceLearningKartika LesmanaNo ratings yet

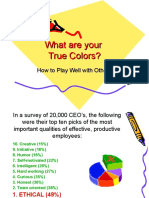

- What Are Your True Colors?Document24 pagesWhat Are Your True Colors?Kety Rosa MendozaNo ratings yet

- Animal Behaviour: Robert W. Elwood, Mirjam AppelDocument4 pagesAnimal Behaviour: Robert W. Elwood, Mirjam AppelputriaaaaaNo ratings yet

- Corporate Strategy in Marine Industries - Module 5Document18 pagesCorporate Strategy in Marine Industries - Module 5Harel Santos RosaciaNo ratings yet

- AI and ML in Marketing (Mentoring)Document21 pagesAI and ML in Marketing (Mentoring)Cinto P VargheseNo ratings yet

- Brain Games 2020 Puzzles KeyDocument31 pagesBrain Games 2020 Puzzles KeyTamal NandyNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Communication Flashcards - QuizletDocument5 pagesIntroduction To Communication Flashcards - QuizletKimberly MagtalasNo ratings yet

- Umi Umd 2239 PDFDocument352 pagesUmi Umd 2239 PDFaifelNo ratings yet

- Test 1 - Thinking and Learning - KEYSDocument1 pageTest 1 - Thinking and Learning - KEYSДарина КоноваловаNo ratings yet

- Most Common Interview Questions AnsweredDocument18 pagesMost Common Interview Questions AnsweredspsinghrNo ratings yet

- Guess The Covered WordDocument4 pagesGuess The Covered Wordapi-259312522No ratings yet

- Senior Practical Research 2 Q1 Module10Document33 pagesSenior Practical Research 2 Q1 Module10Ronnie DalgoNo ratings yet

- Understanding Theories of Relationship DevelopmentDocument42 pagesUnderstanding Theories of Relationship DevelopmentIntan Putri Cahyani100% (1)

- Carleton Arabic Placement Test DetailsDocument9 pagesCarleton Arabic Placement Test DetailsYomna HelmyNo ratings yet

- J Sport Health ResDocument112 pagesJ Sport Health ResViktorNo ratings yet