Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Derwing Munro 2013

Uploaded by

trenadoraquelOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Derwing Munro 2013

Uploaded by

trenadoraquelCopyright:

Available Formats

Language Learning

ISSN 0023-8333

The Development of L2 Oral Language Skills in Two L1 Groups: A 7-Year Study

Tracey M. Derwinga and Murray J. Munrob

a

University of Alberta and b Simon Fraser University

Researching the longitudinal development of second language (L2) learners is essential to understanding inuences on their success. This 7-year study of oral skills in adult immigrant learners of English as a second language evaluated comprehensibility, uency, and accentedness in rst-language (L1) Mandarin and Slavic language speakers. The primary data were judgments at three times from two sets of listeners: native monolingual speakers of English and highly procient English L2 speakers. The Mandarin L1 speakers showed no change over time on any of the dimensions, while the Slavic language L1 speakers improved signicantly in comprehensibility and uency. Improvement in accent was limited to the rst 2 years in the Slavic language group. These outcomes appear to be due to the complex interplay of L1, age, the depth and breadth of learners conversations in English, and their willingness to communicate. Keywords comprehensibility; uency; accent; longitudinal; age; pronunciation

Introduction Policy makers in immigrant receiving countries such as Australia, Canada, and the United States tend to assume that newcomers require a certain prociency level in the language of the community in order to integrate successfully into mainstream society (Burns & De Silva Joyce, 2007; Derwing

The ndings from this research were presented at the 2010 meeting of the American Association for Applied Linguistics, Atlanta, GA. We thank the participants in this study, who agreed to return for an eighth round of testing and interviews. We are grateful to the administrators and staff at NorQuest College and Metro Continuing Education for allowing us to contact the participants at the outset of the study. We thank Ron Thomson, who was involved with the rst seven data collections, and Lori Diepenbroek, Amy Holtby, Jennifer Foote, and Jun Deng, who assisted with the nal round of data collection. We are grateful to the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for two grants awarded to us to carry out this research. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Tracey Derwing, Department of Educational Psychology, 6102 Education North, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB T6G 2G5 Canada. E-mail: Tracey.derwing@ualberta.ca

Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123 C 2013 Language Learning Research Club, University of Michigan DOI: 10.1111/lang.12000

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

& Thomson, 2005; McHugh, Gelatt, & Fix, 2007). In these and other countries, government-funded language instruction programs for adults provide a foundation on which the individual learners are expected to build. For example, in Canada, the federal government funds the Language Instruction for Newcomers to Canada (LINC) program, which is intended to serve as basic language training to adult permanent residents in one of Canadas ofcial languages to facilitate their social, cultural and economic integration into Canada (Dempsey, Xue, & Kustec, 2009, p. 1, emphasis added). Support for more advanced language training is more limited, and is inaccessible for many newcomers. There is an implicit assumption that with basic skills in the majority language, immigrants will continue to develop their second language (L2) at work and in the community. This assumption may have some validity, but it does not apply uniformly to all groups of newcomers. In fact, a recent study of oral language in over 4,000 applicants for Canadian citizenship (M = 6 years residence) showed that differences in rst language (L1) background were tied to differences in prociency (Derwing, Munro, Abbott, & Mulder, 2010). For example, speakers of Russian-Ukrainian scored signicantly higher than speakers of Mandarin on the Canadian Language Benchmark Assessment tool (see http://www.language.ca/). Interpretation of these ndings, however, is complicated by a lack of information about the applicants level of education and knowledge of English on arrival. The current study aims at a closer examination of the same two L1 groups, controlling for level of education, immigration class, oral prociency on arrival, nature of instruction, and length of residence. Background to the Study In Canada, the term integration is not synonymous with assimilation; rather, it is understood to mean that while retaining aspects of their own cultures and languages, immigrants can enjoy full participation in Canadian society. This is in contrast to assimilation, which is interpreted as the complete adoption of the new culture and concomitant abandonment of the traditions of the home culture. The Canadian denition of integration is not universally accepted (cf. Li, 2003), but it is the foundation of federal government policies of multiculturalism. Immigrant integration is typically measured in economic terms, such as annual total income and occupational status (Hum & Simpson, 2004). However, such measures are inuenced by a complex array of factors, such as discrimination, difculties with credential recognition, unavailability of jobs commensurate with immigrants occupational training, and language barriers

Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123 2

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

(Krahn, Derwing, Mulder, & Wilkinson, 2000). Moreover, integration entails much more than economic success. Social, cultural, and linguistic factors are also critical. To test policy makers assumptions about the likelihood that adult immigrants will pick up the language skills they need once they have the basic underpinnings of their L2, it is essential to trace their progress over time. Longitudinal studies of the development of oral L2 skills in adults are rare (Ortega & Iberri-Shea, 2005), yet a full understanding of the factors that affect language learning requires the type of data obtained from such research. In the present study, we address this need by examining the oral language development of two groups of adult learners of English as a second language (ESL): Mandarin and Slavic language (Russian and Ukrainian) speakers. Using a picture narrative task, we evaluated the learners comprehensibility, uency, and accent development over a 7-year period, starting when they were in Stage 1 LINC classes, but continuing well past their formal language training period. These narratives were evaluated by two sets of listeners: native monolingual speakers of English and highly procient English non-native speakers (NNSs). On the basis of the biographical data collected from these participants in our previous studies, we could ascertain that, in many respects, the two learner groups were very similar. At the beginning of the study, all learners were assessed to be beginners in oral language skills, and all had similar government-funded language training experiences, comparable levels of education in their countries of origin, and a shared goal for paid employment in their original occupations. Indeed, the two learner groups were judged to have equal comprehensibility and uency at the outset of the data collection, when they began Stage 1 LINC classes. We have no reason to suspect any between-group difference in aptitude or talent for language learning, which has been shown to have an effect on ultimate attainment in L2 (Abrahamsson & Hyltenstam, 2008; DeKeyser, Al-Shabtay, & Ravid, 2010). The participants differed in some respects. They belonged to one of two language backgrounds: Mandarin, which is not related to English, and Slavic languages (Russian and Ukrainian), which are Indo-European. They also differed in years of L2 study in their home country, age of arrival in Canada, and degree of exposure to and patterns of use of English outside of ESL programming. This variability affords an opportunity to assess the contributions of L1 background and these factors to the development of oral language skills. We are not aware of any studies evaluating a relationship between years of L2 instruction in the country of origin and general language skills on arrival to an immigrant-receiving country, but adult ESL programs for immigrants exist

3 Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

in most inner circle countries to help newcomers further develop their English skills (Derwing, Diepenbroek, & Foote, 2009). Because many skilled immigrants L2 skills on arrival are limited, these programs are intended to develop cultural knowledge and linguistic skills to help them integrate into their new society (Louw, Derwing, & Abbott, 2010). By contrast, there is ample research showing that age of L2 learning is related to ultimate attainment in a number of areas of language, particularly L2 phonology (Flege, Munro, & Mackay, 1995), although most relevant studies have focused on differences between children and adults, rather than examining age effects after adulthood has been reached. The few studies that have addressed L2 development in older learners appear to have mixed results. In a large self-report study, Hakuta, Bialystok, and Wiley (2003) found evidence of a broad decline in L2 ultimate attainment across adulthood. Derwing et al. (2010) observed a similar age-related decline in adult immigrants speaking and listening test scores at the time of citizenship. Baker (2010) found an age-related decline in phonetic skills between ages 20 and 30. DeKeyser et al. (2010), on the other hand, have argued for a plateau between 18 and 40 years of age, based on grammaticality judgments. The present study affords us an opportunity to examine the relationship between age and acquisition of oral skills in adults representing a slightly broader age range, as all our participants arrived in Canada between the ages of 19 and 49. Research Purpose and Expectations In several previous studies, we have reported on the progress of these same participants, examining their English vowel development (Munro & Derwing, 2008), their comprehensibility and uency (Derwing et al., 2008), their accent and uency (Derwing, Thomson, & Munro, 2006), and the relationship between uency in their L1 and their L2 (Derwing, Munro, Thomson, & Rossiter, 2009). These and other studies examined the participants productions in the rst year or rst 2 years of their residence in Canada. In the current study, we focus on the longer-term performance of the same learners by extending the time frame to 7 years, well after their formal ESL training had ended. Improvements in second language skills have been documented over time in several studies (e.g., Lightbown, Halter, White, & Horst, 2002; Klapper & Rees, 2003; Mellow, Reeder, & Forster, 1996). In the current paper, we focus on the ongoing development in three dimensions of oral productions that have been considered in a number of previous investigations: comprehensibility, uency, and accent (e.g., Derwing, Rossiter, Munro, & Thomson, 2004; Derwing et al.,

Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

2008). We dene comprehensibility in terms of listeners perceived difculty of understanding. Fluency refers to listeners perceptions of the ow of the speakers language output, for example, whether there are frequent pauses, false starts, or other dysuencies. Accent is the perceived degree of difference from the local language variety. All three dimensions are evaluated through Likert scaling by untrained listeners. There is no question that the larger group of L2 learners from which the current subset is drawn showed improvement over 2 years on some aspects of English prociency, at the lexical, syntactic, and phonetic levels (Munro & Derwing, 2008). However, when we turned our attention to the three dimensions of comprehensibility, uency, and accent, patterns of improvement for the full sample varied between L1 groups and across the dimensions themselves (Derwing et al., 2008). While both groups improved in accentedness in the rst year of the study, the change was small (Derwing et al., 2006). At 2 years, we also found very little change in the Mandarin L1 speakers uency and comprehensibility despite their enrollment in a language program and residence in a predominantly English-speaking city. The Slavic language speakers, on the other hand, exhibited improvement in both comprehensibility and uency over a 2-year period. In interpreting these ndings, we attributed this between-group effect to differences in both the quality and quantity of the immigrants oral interactions in English. More specically, we proposed that the willingness to communicate (WTC) framework (MacIntyre, 2007; MacIntyre, Cl ement, D ornyei, & Noels, 1998) could account for the motivational, cultural, and interactional differences underlying the performance of the two groups over time. Based on the interview data we collected at the 2-year landmark, the Slavic language speakers were more inclined to seek out opportunities to practice English. Although some of the Mandarin speakers did attempt to nd English-speaking interlocutors, they expressed difculty in sustaining ongoing interactions. Our analysis of the interview data suggested that factors within the WTC model, such as intergroup climate, social situation, communicative competence, L2 self-condence, and motivation contributed to the differential outcomes between the Mandarin and Slavic language speakers (Derwing et al., 2008). The current research extends our previous investigations 5 years after completion of those earlier studies, with the expectation that, provided there have been no dramatic changes in frequency of use, the comprehensibility and uency of the two groups of learners will continue to diverge. In other words, the Mandarin speakers will show little or no improvement 5 years after the last

Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

testing point, but the Slavic language speakers will be perceived as more comprehensible and more uent. We would not expect accents to change in either group for several reasons. First, the limited evidence available suggests that accents tend to stabilize within the rst year in the absence of explicit pronunciation instruction (Flege, 1988). Second, prior research indicates that accent is of less communicative value than comprehensibility, in that speakers may be highly comprehensible despite strong foreign accents (Munro & Derwing, 1999). Finally, because all our participants showed more limited early improvement in accent than in the other dimensions, we hypothesize that there would be less change after 7 years in accent than in either uency or comprehensibility.

Method Speakers The speakers were 11 Mandarin and 11 Slavic language speakers (7 Russians and 4 Ukrainians) who were participants in a larger longitudinal study of L2 acquisition. Previous research on these speakers rst 2 years of language development was presented in Derwing et al. (2008) and Munro and Derwing (2008). Not all of the original participants were available at the 7-year point, on which we are reporting here. Because only 11 Mandarin speakers were tested at each of the 2-month, 2-year, and 7-year points, we restricted the number of Slavic language speakers to 11 as well, by randomly selecting from the 17 who were eligible. There were 6 Mandarin females and 5 males, ranging in age from 35 to 47 at Year 7 (M = 42), and 6 Slavic language females and 5 males, ranging in age from 27 to 56 at Year 7 (M = 45.8). We also included three female monolingual English speakers, who provided speech samples. These were later used to verify that the listeners remained in step during the listening task. Listeners Listeners were recruited through posters in the Education building at the University of Alberta. We recruited two sets of listeners: monolingual NSs of English and highly procient English NNSs. The criteria for participation for both sets included undergraduate or graduate student status in a regular (nonESL) academic program, age under 50 years, and normal hearing. Eventually three listeners were dropped (2 NSs and 1 NNS) because of noncompliance with the task instructions, leaving 34 native listeners (12 males, 22 females) of Canadian English (average age = 22 years, range 1837) and another 10

Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

(1 male, 9 females) who were high prociency L2 speakers of English (2 Mandarin, 2 Cantonese, and 1 each of Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, Tagalog, Ukrainian, and Vietnamese)1 with an average age of 26 years (range 1842). The proportions of NS and NNS respondents reect the composition of the student body in the faculty. All listeners were students at the University of Alberta (and thus met the language requirements for admission to an English-speaking university). All reported normal hearing. All were paid an honorarium of $20 for their participation. Stimuli At each test point (2 months into the study, and the 2-year and 7-year points) all the speakers produced narratives based on an 8-frame cartoon story about a man and a woman who mistakenly switched suitcases. High-quality digital recordings were made at the learners schools or in a quiet lab. A 2025-second excerpt was extracted from the beginning of each narrative and normalized to remove variation in volume. The excerpts from all three time periods were then randomized for presentation to the listeners.

Rating Procedure The procedure was the same as that followed in numerous other studies of the speech dimensions evaluated here (Munro & Derwing, 1999; Derwing & Munro, 1997; Munro, Derwing, & Morton, 2006; Derwing et al., 2008). Multiple listening sessions were held in a quiet room to accommodate the listeners schedules. During these sessions, the listeners completed a language background questionnaire and then viewed the cartoon story on which the narratives were based to minimize familiarity effects. They then heard one of three different randomizations of the 70 stimuli and rated each item for comprehensibility (on a scale ranging from 1 = easy to understand to 9 = extremely difcult to understand ), uency (on a scale ranging from 1 = extremely uent to 9 = extremely dysuent), and accentedness (on a scale ranging from 1 = no accent to 9 = extremely strong accent). Instructions on how to use the scales and what the anchor terms meant were provided both in writing and orally (see the Appendix). The listeners heard each complete sample only once before making their judgments and were instructed to use the entire scale. Prior to completing the task, they rated three practice items (not used in the experiment). They were given a 3-minute break partway through the experiment to reduce fatigue. An experimenter controlled the playback of the stimuli to ensure that all raters

7 Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

stayed in step. Total time for the task was approximately 50 minutes. A short debrieng of the listeners took place after the experiment. Biographical Data Finally, we used biographical information about years of English study in the country of origin and age on arrival to Canada that we had collected from our Mandarin and Slavic language participants in the earlier studies. We also elicited data at the 7-year point, through interviews (to be reported elsewhere) and a questionnaire about self-reported frequency of conversations in English. The participants indicated how often they engaged in conversations of 10 minutes or more on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (several times a day). We did not consider shorter conversations because they were likely to be routine and formulaic and thus less likely to contribute to enhanced comprehensibility and uency. Results The ratings of the three female monolingual NS speech samples were not included in any of the statistical analyses that follow. As mentioned above, three listeners were dropped because they did not follow the instructions (e.g., the judgments were made before the speech sample was completed or responses were changed long after items had been played). From among the raters retained, all comprehensibility and accent judgments of the NS speech samples were scored at one or two. Furthermore, with the NNS speech samples, 95% or more of the native listeners assigned at least one score of 9 or 8 at the other end of each of the three scales. For the non-native listeners, 80% or more did so. The data thus indicated that, as in previous studies, the listeners had recognized the NSs in the samples, had stayed in step throughout the task, and had followed the instruction to use the full scales as much as possible. Reliability of Ratings and Comparison of the Two Listener Groups To evaluate reliability across raters, we computed the intraclass correlations (Shrout & Fleiss, 1979) for the three measures for each group of listeners. For the 34 native English listeners, high reliability was observed on comprehensibility (r = .959), uency (r = .971), and accentedness (r = .950). For the 10 non-native listeners, reliability was slightly lower, though still very satisfactory (r = .868, .926, and .896, respectively). Because the intraclass correlation is sensitive to the number of judges, the slightly lower scores may be due to the smaller sample size.

Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123 8

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

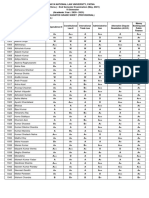

We computed Pearson correlations for the mean ratings from the two listener groups (English NSs and highly procient NNSs) to determine how similar their ratings of the speech samples were. The correlations for comprehensibility and uency were very high (r = .94 and r = .95, respectively) and just slightly lower for accent (r = .88), p < .01 in all cases. Nevertheless, data were analyzed separately in most of the results presented below, as we wanted to determine whether native and bilingual listeners responded to aspects of the L2 language samples in similar ways and whether they held similar perceptions of improvement. Effects of Time and L1 on Judgments Mean ratings for each learner on each scale were submitted to a series of mixed-design analyses of variance (ANOVAs) with L1 (Mandarin or Slavic language) as the between-groups factor, and Test Time (2 months, 2 years, 7 years) as the within-groups factor. Table 1 shows the results of the ANOVAs for both listener groups, including effect sizes (partial eta squared) for the results that were statistically signicant. The rst set of ANOVAs evaluated changes in comprehensibility ratings over time, while the second and third sets focused on uency and accent. A criterion of p < .05 was adopted for statistical signicance. For all three dimensions, the effect of speaker L1 missed signicance, while the effect of Time was signicant, as was the L1 Time interaction (see Table 1). This pattern was observed for both the native English and non-native listener ratings. Figures 1a3b illustrate the ratings of the groups of listeners for comprehensibility, uency, and accentedness across the three times. In each pair of gures the native English listener judgments appear on the top, with those of the non-native listeners below. Pairwise Bonferroni adjusted (p < .05) t tests were calculated to explore the interactions. In general, these revealed signicant improvement over time for the Slavic group but not the Mandarin group (see Table 2). In all but one case, the native English and bilingual listeners showed identical patterns. Neither listener group perceived an improvement in comprehensibility, uency, or accentedness across any of the times for the Mandarin speakers. By contrast, parallel tests on the Slavic language group revealed signicant improvement in comprehensibility from 2 months to 2 years, 2 months to 7 years, and 2 years to 7 years. For uency, both the NS and NNS listener groups judged that the Slavic language group improved between 2 months and 2 years and between 2 months and 7 years. However, for the NNS listeners the difference between the 2-year and 7-year scores was marginal (p = .035 with a Bonferroni criterion

9 Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123

Derwing and Munro

Table 1 Results of mixed-design analyses of variance with L1 and time as factors Listener Group NS (N = 34) p = .30 p < .001, p 2 = .48 p < .001, p 2 = .413 p = .07 p < .001, p 2 = .47 p = .001, p 2 = .30 p = .82 p < .001, p 2 = .47 p = .002, p 2 = .28 F (1, 20) = 3.40 F (2, 40) = 15.82 F (2, 40) = 5.76 F (1, 20) = 1.03 F (2, 40) = 17.19 F (2, 40) = 5.45 F (1, 20) = 1.92 F (2, 40) = 15.57 F (2, 40) = 8.32 NNS (N = 10) p = .182 p < .001, p 2 = .44 p < .001, p 2 = .29 p = .08 p < .001, p 2 = .44 p = .006, p 2 = .22 p = .32 p < .001, p 2 = .46 p =.008, p 2 = .21

Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123

Source

Comprehensibility L1 Time L1Time

F (1, 20) = 1.14 F (2, 40) = 18.44 F (2, 40) = 14.09

Fluency L1 Time L1Time

F (1, 20) = 3.66 F (2, 40) = 17.92 F (2, 40) = 8.59

Accentedness L1 Time L1Time

F (1, 20) = .05 F (2, 40) = 17.79 F (2, 40) = 7.64

Development of L2 Oral Skills

Note. NS = native monolingual speakers of English, NNS = highly procient non-native speakers of English

10

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

a

Comprehensibility

1 3 5 7 9 2 month 2 year 7 year Mandarin Slavic

b

Comprehensibility

1 3 5 7 9 2 month 2 year 7 year Mandarin Slavic

Figure 1 Mean comprehensibility ratings from native English listeners (a) and nonnative listeners (b) for the two speaker groups at 2 months, 2 years, and 7 years.

1 3

1 3

Fluency

Fluency

5 7 9 2 month 2 year 7 year

Mandarin Slavic

5 7 9 2 month 2 year 7 year

Mandarin Slavic

Figure 2 Mean uency ratings from native English listeners (a) and non-native listeners (b) for the two speaker groups at 2 months, 2 years, and 7 years.

of p < .017), while the NS listeners perceived a signicant improvement. For accentedness ratings, both listener groups judged that the Slavic speakers improved from 2 months to 2 years and from 2 months to 7 years, but not from 2 years to 7 years. In sum, as expected, the Mandarin speakers showed little or no improvement 5 years after the last testing point, whereas the Slavic language speakers were perceived as more comprehensible and more uent. In other words, the comprehensibility and uency scores observed in the two groups of learners after 2 years of residence in Canada continued to diverge over 7 years in the country. Accent scores, however, did not change from the 2-year to the 7-year point. To gain deeper insights into the performance of the individual participants, we plotted their scores from 2 years and 7 years for comprehensibility and

11 Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

a

1 Accentedness 3 5 7 9 2 month 2 year 7 year Mandarin Slavic

b

1 Accentedness 3 5 7 9 2 month 2 year 7 year Mandarin Slavic

Figure 3 Mean accent ratings from native English listeners (a) and non-native listeners (b) for the two speaker groups at 2 months, 2 years, and 7 years. Table 2 Perceived improvement over time in the Mandarin (M) and Slavic language (S) groups by two groups of listeners (results of Bonferroni tests) NS (N = 34) Scale L1 2 m-2 yr 2 m-7 yr 2 yr-7 yr 2 m-2 yr NNS (N = 10) 2 m-7 yr 2 yr-7 yr

Comprehensibility M No S Yes Fluency M S Accent M S No Yes No Yes

No Yes No Yes No Yes

No Yes No Yes No No

No Yes No Yes No Yes

No Yes No Yes No Yes

No Yes No No No No

Note. NS = native monolingual speakers of English, NNS = highly procient non-native speakers of English

uency (see Figures 4a5b). In each case, results for the Mandarin speakers are shown in the top panel, and those for the Slavic language speakers are in the bottom panel. Because the two groups of listeners provided such similar ratings, we report here only the judgments of the larger native English group. The dotted lines in the gures indicate numerically worse ratings at 7 years, while solid lines indicate an improvement. The most striking differences between the two participant groups are in comprehensibility, where 7 Mandarin speakers actually showed worse performance at 7 years, as compared with only 2 from the

Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123 12

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

a

Comprehensibility 1 3 5 7 9 2 year 7 year

b

Comprehensibility

1 3 5 7 9 2 year 7 year

Figure 4 Individual comprehensibility ratings for the Mandarin (a) and the Slavic language (b) speakers at the 2-year and 7-year points.

a

Fluency

1 3 5 7 9 2 year 7 year

b1

Fluency 3 5 7 9 2 year 7 year

Figure 5 Individual uency ratings for the Mandarin (a) and the Slavic language (b) speakers at the 2-year and 7-year points.

speakers in the Slavic language group. Furthermore, 5 of the Slavic speakers were rated better at 7 years than the best Mandarin speaker. Figures 5a and 5b show a net uency improvement in 4 Mandarin speakers but in 8 Slavic language speakers; 7 of those scored better than the best Mandarin speaker. For accent (not shown because of the lack of L1-related differences), 6 members of each group were judged to show a net improvement.

Effects of Years of Prior English Study, Age of Arrival, and Amount of English Use Years of English study in the country of origin did not correlate signicantly with comprehensibility, uency, or accentedness scores at the 7-year point (r(20) = .235, .376, and .11, respectively, p > .05). The participants ages on arrival in Canada ranged from 19 to 49 years, all within working age. Age on arrival was signicantly correlated with comprehensibility scores for the combined groups after 7 years, r(20) = .424. When the correlation was

13 Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

1 3 5 7 9 15 25 35 45 Age of Arrival in Canada 55

Figure 6 Correlation of accent ratings with age of arrival in Canada for all speakers. A regression line has been added.

computed for Mandarin speakers alone, the nding was r(9) = .372, p > .05, and for Slavic speakers it was r (9) = .774, p = .005. Age on arrival was also signicantly correlated with accent scores after 7 years, r(20) = .638, p <. 05, (r (9) = .482, p > .05, for Mandarin speakers alone and r(9) = .831, p = .002, for Slavic speakers alone). The correlation with accent for both groups combined is illustrated in Figure 6. Later ages of arrival were thus associated with poorer performance on both these variables. However, age was not correlated with uency scores for the combined groups, r(20) = .384, p > .05, despite higher correlations for the individual groups (Mandarin speakers r(9) = .616, p = .044; Slavic language speakers r(9) = .793, p = .004). It is important to interpret these correlations with caution because of the small sample sizes. When partial correlations for these variables were computed for both groups combined, controlling for years of English study in the country of origin, age of arrival was still signicantly correlated with both comprehensibility and accent scores, r(20) = .444 and .645, respectively, p < .05. The partial correlation between age and uency was marginal, r(20) = .426, p = .05. Finally, we considered the participants reported frequency of conversations of 10 minutes or more. There was very little shift in the frequency of conversations in English from the 2-year to the 7-year point. Of the entire set of 22 speakers, only 5 reported increased numbers. We then compared comprehensibility scores at the 7-year point with participants reported frequency of conversations in English at both the 2-year and the 7-year points. We did so because comprehensibility yielded the most striking 7-year differences between the two participant groups (cf. Figures 4a and 4b). The two weakest performers were both Mandarin speakers who reported less than one English

Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123 14

Accentedness

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

conversation of 10 minutes or more per day at the 2-year test; neither exhibited an increase in conversation frequency over the intervening 5 years. The two Mandarin speakers who were rated most comprehensible, on the other hand, reported having extensive interactions in English on a daily basis at both the 2-year and 7-year points. Discussion This longitudinal study was intended to determine to what extent adult immigrant L2 learners continued to make progress in the development of oral English skills after their formal ESL training in Canada. In particular, it explores whether policy makers are correct in assuming that newcomers will continue to acquire English without further instruction after foundational language skills have been developed. Following well-established procedures, extemporaneous narratives produced by two groups of speakers at 2 months, 2 years, and 7 years were evaluated by listeners for comprehensibility, uency, and accentedness in a blind rating task. The 11 Slavic language speakers improved in comprehensibility and uency both during the time they were enrolled in an ESL program and afterward, while accentedness improved only during the rst 2 years. The 11 Mandarin speakers, on the other hand, showed much less improvement, with most of them making no perceptible gains across the entire 7-year study in any of the three dimensions of comprehensibility, uency, or accentedness. In addition, their ratings across all three dimensions remained markedly worse over the 7-year span than the ratings given to the Slavic group. The rating task ndings are also further testament to the fact that accent and comprehensibility are partially independent; an improvement in comprehensibility does not necessarily require that strength of accent be diminished (Derwing, Munro, & Wiebe, 1998). In this section, we discuss the ndings and propose some explanations. We argue that the between-group differences appear to be the result of the complex interplay of rst language, the extent of linguistic interactions in the L2, and overall WTC. Years of Formal English Language Training in Country of Origin It might be assumed that a greater amount of English study prior to arrival in Canada would afford an advantage to immigrants. There was no indication of such an advantage for the participants here, however. First, all of them were placed at a beginner level in speaking and listening by the central assessment centre in their city. Second, our analyses yielded no signicant correlations

15 Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

at any of the three times between comprehensibility or uency and years of English study in their countries of origin prior to arrival in Canada. While this nding may seem unexpected, the participants were all adult immigrants, and even though many of them had studied English in school, they may not have anticipated having to use it extensively later on in life. Although one might expect an advantage at least at the 2-month stage of the current study (e.g., faster lexical access), the fact that most of the foreign language courses in their countries of origin were focused primarily on written language may have precluded a benet in the development of oral skills. Effect of Age of Arrival The nding of a correlation between age of arrival in Canada and comprehensibility scores after 7 years contributes to the small but growing body of evidence that the level of ultimate L2 attainment decreases steadily across the lifespan. Furthermore, the older arrivals in this study showed a marked tendency to have stronger accents than younger arrivals. These ndings were observed in learners between the ages of 19 and 49, a time period that is thought to be relatively stable for grammatical learning (DeKeyser et al., 2010). However, Baker (2010) noted a decline in Korean English speakers performance on word nal stops depending on whether they arrived in the United States in their 20s or 30s. Our ndings, therefore, appear to conrm that pronunciation learning is subject to age effects even during adulthood. A Comparison of the Mandarin and Slavic Language Learners Performance Our choice of the two L1 groups allows us to examine learning trajectories for learners from very different linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Historically, these two L1 groups are signicantly represented in Canadas immigrant population, and to this day Canada receives large numbers of newcomers who speak either Mandarin or a Slavic language as their L1. Given the importance of these L1 groups, we wanted to compare their learning performance for both theoretical and pedagogical reasons. Of course there is an important L1 difference here, in that Slavic languages are Indo-European and thus show some lexical and structural similarities to English, which undoubtedly contributed to some of the differences in the outcomes. However, in Derwing et al. (2008), we found that the WTC framework (MacIntyre et al., 1998) was especially helpful in accounting for between group differences for the larger sample from which the current participants are drawn. In that study, the Mandarin and Slavic language speakers were judged to have equal comprehensibility and uency at

Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123 16

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

the outset, but the Mandarin speakers were less comprehensible and less uent than the Slavic language speakers after 10 months and 2 years in Canada. The WTC framework accounts for communication behavior on the basis of factors such as intergroup climate, intergroup attitudes, L2 self-condence, and social situation. A qualitative analysis of the interview data at the 2-year point indicated that the participants reections on their language learning and their own situations t the framework very well. The Mandarin speakers overall showed greater ties to their L1 community, more reluctance to initiate conversations as a result of lower self-condence in their English abilities, and fewer opportunities to interact in English. The outcomes for comprehensibility, uency, and accent at 7 years are remarkably similar to those seen at the 2-year point. In other words, the Mandarin speakers continue to make few or no gains, while the Slavic language speakers continue to improve in both comprehensibility and uency. Interestingly, neither group showed any improvement in accentedness between Year 2 and Year 7, despite the signicant improvement in comprehensibility evidenced in the Slavic language group. In Derwing et al. (2008), we concluded that overall experience with an L2, as determined by WTC factors, affected L2 oral development. In this study, at the 7-year point, the ndings are similar. The two Mandarin speakers rated best on comprehensibility at 7 years also reported high levels of exposure to English on a daily basis at the 7-year point. In contrast, the two with the worst comprehensibility scores were also the two who reported the least daily exposure after 7 years in Canada. When asked at the 7-year point what advice on language learning the participants would give to newcomers to Canada, the Mandarin speaker judged to be least comprehensible, who also had the least contact with English interlocutors said, I think rst, always talk, talk with people. If you have any time, any chance. Native English and L2 English Listeners A unique feature of this study was the elicitation and comparison of ratings from two groups of listeners, 34 NSs of English and 10 high-prociency NNSs of English. These two groups showed remarkably parallel ratings; overall reliability within each group was high and the two groups scores correlated with each other at high levels, suggesting that native and bilingual listeners responded to aspects of the L2 language samples in similar ways. With respect to perceptions of improvement, there was only one difference between the two groups: The native English listeners perceived a signicant improvement in uency for the Slavic language speakers between the 2-year and 7-year points, whereas the non-native listeners scores showed only a marginal trend in the

17

Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

same direction. The strong similarities between the ratings of the native and bilingual listeners are important because they indicate that the high prociency L2 listeners in this study interpreted oral productions in a manner very similar to the native listeners. That is, a speaker who was perceived as having low comprehensibility and low uency by native English listeners was perceived the same way by procient NNSs. The fact that the non-native listeners in this study came from a diverse range of L1 backgrounds makes this outcome all the more impressive. They appear to share a similar criterion with NSs for what constitutes easy to understand and uent speech in Canadian English. These ndings replicate and extend other research studies. Flege (1988), for instance, found strong similarities in accent ratings of Taiwanese, Mandarin, and English native listeners who judged Mandarin-accented English speech. Mackay, Flege, and Imai (2006) found a close relationship between native English speakers and Arabic speakers judgments of Italian-accented English. Finally, Munro et al. (2006) had Cantonese, Japanese, Spanish, and Polish native listeners evaluate non-native speech samples from speakers of those same languages. Scores on intelligibility, comprehensibility, and accentedness were again highly similar across listener groups. Furthermore, the scores were also similar to those elicited from English native listeners in Derwing and Munro (1997). Thus, even though factors such as bias (Kang & Rubin, 2009) and familiarity (Gass & Varonis, 1984) can inuence responses to L2 speech, listeners are nonetheless powerfully inuenced by properties of the speech signal itself. Implications and Conclusion Given the central nding of the current studythat the two groups of learners differed dramatically in their progress in oral English over a 7-year periodwe reiterate Ortega and Iberri-Sheas (2005) call for more longitudinal studies in applied linguistics. A diverse range of L1 groups should be investigated to fully understand factors that contribute to ultimate attainment. It is only with longitudinal studies that we can observe the outcomes of language instruction and interaction in the target community. This type of study can inform policy makers who are charged with determining the allocation of resources to immigrant language training. Our research shows that so-called basic language skills are insufcient for some newcomers to ensure full integration, even after a long period of 7 years living and working in the country. The study also suggests that ESL programs should put a greater focus on oral language skills in the

Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123

18

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

beginner stages of language acquisition, particularly because some L2 students do not access much oral language outside the classroom. A limitation here is the somewhat crude measure of frequency and amount of oral language use as measured by self-reported length of interactions in English (frequency of conversations of 10 minutes or more). Of the more sophisticated approaches that have been proposed, experience sampling (Kubey, Larson, & Csikszentmihalyi, 1996) would not be suitable for the lifestyles of the speakers in this study. However, an electronic language log, along the lines of that employed by Ranta and Meckelborg (2008), might be feasible. Improved measures of patterns of L2 use and oral interaction with greater detail may point to ways in which to enhance learners WTC, a fundamental goal for pedagogy (MacIntyre et al., 1998). In addition, one aspect of the method used in this rating study was the xed order of comprehensibility, uency, and accent ratings from the listeners. We opted to assess comprehensibility rst because of its primacy in communication. However, additional research could explore whether there is an order effect in such judgment tasks. This study featured two sets of listeners, NSs of English and highly procient bilingual speakers from a wide range of L1 backgrounds. The striking congruence of the two groups ratings suggests that studies of oral prociency need not restrict listeners to one group or the other. However, the level of L2 prociency required for bilinguals to assess L2 speech reliably has not been established. More research is necessary to determine whether there is a threshold of prociency in an L2 to make such judgments. Although it is possible for listeners to detect a foreign accent in a language they do not speak (Major, 2007), such an ability does not extend to comprehensibility, which requires some as yet unknown level of knowledge of the L2. Finally, correlational analyses carried out with relatively small numbers of participants have to be interpreted with caution. Our nding of a relationship between age of learning and comprehensibility and accent scores for adults between 19 and 49 years at the outset of the study should be tested with a larger number of learners. Although DeKeyser et al.s (2010) examination of grammaticality did not yield such an effect, it may be that pronunciation is subject to different constraints. Learning a new language and integrating into a new workplace, a new community, and a new society are challenging endeavors. If language programs are to facilitate these processes they should take into account the factors that inuence ultimate attainment. This study, in particular, points to the importance of WTC and its relationship to L1s as a factor in successful acquisition of oral

19

Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

language skills. It is clear that one-size-ts-all programs will not serve the needs of all learners, as this longitudinal study demonstrates.

Final revised version accepted 3 January 2012

Note

1 We did not attempt to compare the Mandarin, Russian, and Ukrainian listeners ratings with the others because the numbers did not warrant it.

References

Abrahamsson, N., & Hyltenstam, K. (2008). The robustness of aptitude effects in near-native second language. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 30, 481509. Baker, W. (2010). Effects of age and experience on the production of English word nal stops by Korean speakers. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 13, 263278. Burns, A., & De Silva Joyce, H. (2007). Adult ESL programs in Australia. Prospect, 22(3), 517. DeKeyser, R. Al-Shabtay, I., & Ravid, D. (2010). Cross-linguistic evidence for the nature of age effects in second language acquisition. Applied Psycholinguistics, 31, 413438. Dempsey, C., Xue, L., & Kustec, S. (2009). Language instruction for newcomers to Canada: Performance results by LINC level. Ottawa: Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Derwing, T. M., Diepenbroek, L., & Foote, J. (2009). A literature review of English language training in Canada and other English-speaking countries. Unpublished report prepared for Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Derwing, T. M., & Munro, M. J. (1997). Accent, comprehensibility and intelligibility: Evidence from four L1s. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19, 116. Derwing, T. M., Munro, M. J., Abbott, M., & Mulder, M. (2010). An examination of the Canadian language benchmark data from the citizenship language survey. Retrieved from http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/research/language-benchmark/index. asp Derwing, T. M., Munro, M. J., & Thomson, R. I. (2008). A longitudinal study of ESL learners uency and comprehensibility development. Applied Linguistics, 29, 359380. Derwing, T. M., Munro, M. J., Thomson, R. I., & Rossiter, M. J. (2009). The relationship between L1 uency and L2 uency development. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 31, 533557. Derwing, T. M., Munro, M. J., & Wiebe, G. (1998). Evidence in favor of a broad framework for pronunciation instruction. Language Learning, 48, 393410.

Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123 20

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

Derwing, T. M., Rossiter, M. J., Munro, M. J., & Thomson, R. I. (2004). L2 uency: Judgments on different tasks. Language Learning, 54, 655679. Derwing, T. M., & Thomson, R. I. (2005). Citizenship concepts in LINC classrooms. TESL Canada Journal, 23(1), 4462. Derwing, T. M., Thomson, R. I., & Munro, M. J. (2006). English pronunciation and uency development in Mandarin and Slavic speakers. System, 34, 183193. Flege, J. E. (1988). Factors affecting degree of perceived foreign accent in English sentences. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 84, 7079. Flege, J. E., Munro, M. J., & MacKay, I. R. A. (1995). Factors affecting strength of perceived foreign accent in a second language. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 97, 31253134. Gass, S. M., & Varonis, E. M. (1984). The effect of familiarity on the comprehensibility of nonnative speech. Language Learning, 34, 6589. Hakuta, K., Bialystok, E., & Wiley, E. (2003). Critical evidence: A test of the critical-period hypothesis for second-language acquisition. Psychological Science, 14, 3138. Hum, D., & Simpson, W. (2004). Economic integration of immigrants to Canada: A short survey. Canadian Journal of Urban Research, 13, 4661. Kang, O., & Rubin, D. L. (2009). Reverse linguistic stereotyping: Measuring the effect of listener expectations on speech evaluation. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 28, 441456. Klapper, J., & Rees, J. (2003). Reviewing the case for explicit grammar instruction in the university foreign language learning context. Language Teaching Research, 7, 285314. Krahn, H., Derwing, T. M., Mulder, M., & Wilkinson, L. (2000). Educated and underemployed: Refugee integration into the Canadian labour market. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 1, 5984. Kubey, R., Larson, R., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Experience sampling method applications to communication research questions. Journal of Communication Research, 46, 99120. Li, P. (2003). Deconstructing Canadas discourse of immigrant integration. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 4, 315333. Lightbown, P., Halter, R., White, J., & Horst, M. (2002). Comprehension-based learning: The limits of do it yourself. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 58, 427464. Louw, K. J., Derwing, T. M., & Abbott, M. L. (2010). Teaching pragmatics to L2 learners for the workplace: The job interview. Canadian Modern Language Review, 66, 739758. MacIntyre, P. D. (2007). Willingness to communicate in the second language: Understanding the decision to speak as a volitional process. Modern Language Journal, 91, 564576.

21 Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

MacIntyre, P. D., Cl ement, R., D ornyei, Z., & Noels, K. A. (1998). Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in a L2: A situational model of L2 condence and afliation. Modern Language Journal, 82, 545562. Mackay, I. R. A., Flege, J. E., & Imai, S. (2006). Evaluating the effects of chronological age and sentence duration on degree of perceived foreign accent. Applied Psycholinguistics, 27, 157183. Major, R. (2007). Identifying a foreign accent in an unfamiliar language. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 29, 539556. McHugh, M., Gelatt, J., & Fix, M. (2007). Adult English language instruction in the United States: Determining need and investing wisely. Retrieved from http://www.migrationinformation.org/integration/language.cfm Mellow, J. D., Reeder, K., & Forster, E. (1996). Using the time-series design to investigate the effects of pedagogic intervention on SLA. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 18, 325350. Munro, M. J., & Derwing, T. M. (1999). Foreign accent, comprehensibility and intelligibility in the speech of second language learners. Language Learning, 49, Supplement 1, 285310. Munro, M. J., & Derwing, T. M. (2008). Segmental acquisition in adult ESL learners: A longitudinal study of vowel production. Language Learning, 58, 479502. Munro, M. J., Derwing, T. M., & Morton, S. (2006). The mutual intelligibility of L2 speech. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28, 11131. Ortega, L., & Iberri-Shea, G. (2005). Longitudinal research in second language acquisition: Recent trends and future directions. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 25, 2645. Ranta, L., & Meckelborg, A. (2008, April). Questioning the language exposure questionnaire. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Association of Applied Linguistics, Washington, DC. Shrout, P. E., & Fleiss, J. L. (1979). Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin, 2, 420428.

Appendix: Oral Instructions Provided to Raters You will hear both second language learners and NSs of English describing the storyall of the speech samples are taken from the rst 2025 seconds. What we would like you to do is make three judgments about each sample. First, we will ask you to say how easy or difcult the sample is to understand, using a 9-point scale. You might be able to understand everything but it may require a lot of effort on your partso what we are interested in is the effort you put in. Can you understand it without even thinking about it, or do you have to work at it?

Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123 22

Derwing and Munro

Development of L2 Oral Skills

Second, we will ask you to rate uency. This is the ow of the language does the person have problems nding words, using a lot of ums and ahs, or pauses, or do the words come easily? Dont worry about grammar mistakes that doesnt matter. So, someone who is very uentthat is, the words just ow with no struggle, would be at the left end of the scale, while someone who has a hard time expressing him or herself would be closer to the right end of the scale. Third, we are interested in accent. We all have accents, but what we are interested in knowing is how different the speakers accents are from a standard Canadian English accent. Accent is different from comprehensibilityyou might be able to understand somebody easily and still hear a heavy accent. Again the scale is 19: 1 = no accent and 9 = extremely heavy accent. We would like you to try to use the whole scale over the course of the experiment. Please listen to the whole sample before making your decisions.

23

Language Learning XX:X, XXXX 2013, pp. 123

You might also like

- Group Counseling Outline For Elementary Aged GirlsDocument18 pagesGroup Counseling Outline For Elementary Aged GirlsAllison Seal MorrisNo ratings yet

- RW3 Answer KeyDocument17 pagesRW3 Answer KeyThanhDâuNo ratings yet

- One-To-One Methodology - Ten Activities - Onestopenglish PDFDocument2 pagesOne-To-One Methodology - Ten Activities - Onestopenglish PDFnettie7o7blackNo ratings yet

- Cambridge English Proficiency Reading and Use of English Part 2Document4 pagesCambridge English Proficiency Reading and Use of English Part 2PepepereirasNo ratings yet

- World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2013, List of Participants As of 7 January 2013Document63 pagesWorld Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2013, List of Participants As of 7 January 2013American KabukiNo ratings yet

- Using Role Play Activities To Teach The Present Perfect TenseDocument17 pagesUsing Role Play Activities To Teach The Present Perfect TenseSofii VictoriannaNo ratings yet

- Methods of TeachingDocument11 pagesMethods of TeachingnemesisNo ratings yet

- All ConditionalsDocument12 pagesAll ConditionalsJulio OrozcoNo ratings yet

- Group 3 Global Media CulturesDocument27 pagesGroup 3 Global Media CulturesLouwell Abejo RiñoNo ratings yet

- Derwing (2007) - A Longitudinal Study of ESL Leaners' Fluency PDFDocument22 pagesDerwing (2007) - A Longitudinal Study of ESL Leaners' Fluency PDFManuela PeñaNo ratings yet

- Error Correction PowerpointDocument17 pagesError Correction PowerpointPulkit Vasudha100% (1)

- Distance Dimensions SizeDocument2 pagesDistance Dimensions SizeJosé Manuel Henríquez Galán100% (1)

- The Role of Prior Knowledge in L3 LearningDocument25 pagesThe Role of Prior Knowledge in L3 LearningKarolina MieszkowskaNo ratings yet

- (123doc) A Pragmatic Study On Apology in English and VietnameseDocument76 pages(123doc) A Pragmatic Study On Apology in English and VietnamesehientrangngoNo ratings yet

- Unit 7A - Modals of Deduction & Buildings PDFDocument8 pagesUnit 7A - Modals of Deduction & Buildings PDFнеизвестноNo ratings yet

- Alan Duff's TranslationDocument15 pagesAlan Duff's TranslationUmerBukhariNo ratings yet

- Exam Practice C (v1) P1 T3, P2 T3 FileDocument2 pagesExam Practice C (v1) P1 T3, P2 T3 FileNaserElrmahNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan in Mathematics Grade 3 Quarter Four Week Ten Day OneDocument34 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in Mathematics Grade 3 Quarter Four Week Ten Day OneJohn Paul Dela Peña86% (7)

- Demystifying The Complexity of Washback Effect On LearnersDocument16 pagesDemystifying The Complexity of Washback Effect On LearnersHenriMGNo ratings yet

- 1 ENG709 Course Design and Material DevelopmentDocument5 pages1 ENG709 Course Design and Material DevelopmentvyNo ratings yet

- NguamphiluanDocument112 pagesNguamphiluanMai Linh100% (1)

- Đề Thi Kết Thúc Học PhầnDocument3 pagesĐề Thi Kết Thúc Học PhầnJames MessianNo ratings yet

- ESOL International English Speaking Examination Level C2 ProficientDocument7 pagesESOL International English Speaking Examination Level C2 ProficientGellouNo ratings yet

- The Similarities and Differences in Expressing Apology in English and VietnameseDocument7 pagesThe Similarities and Differences in Expressing Apology in English and VietnamesePoonam KilaniyaNo ratings yet

- Week 1: Complete The Sentences Below. Write No More Than Three Words And/Or A Number For Each AnswerDocument3 pagesWeek 1: Complete The Sentences Below. Write No More Than Three Words And/Or A Number For Each AnswerViễn Phúu67% (3)

- Study 3Document1 pageStudy 3mamo nano100% (1)

- Focus On Academic Skills For IeltsDocument165 pagesFocus On Academic Skills For IeltsĐinh Lý Vân KhanhNo ratings yet

- Sematics Unit 9 - PT 1-Sense Properties and StereotypesDocument28 pagesSematics Unit 9 - PT 1-Sense Properties and StereotypesHilma SuryaniNo ratings yet

- Apology Strategies in English and VietnameseDocument36 pagesApology Strategies in English and VietnameseblazsekNo ratings yet

- HCMC University of Education Department of English - ELT Section Module 2 - MainstreamDocument10 pagesHCMC University of Education Department of English - ELT Section Module 2 - MainstreamphuongNo ratings yet

- 4B07 NguyenThiMyNgan A Contrastive Analysis of Refusing An Offer in English and VietnameseDocument27 pages4B07 NguyenThiMyNgan A Contrastive Analysis of Refusing An Offer in English and Vietnamesephamxiem100% (2)

- 7 READING COMPREHENSION EXERCISE Studying Abroad An Enriching ExperienceDocument4 pages7 READING COMPREHENSION EXERCISE Studying Abroad An Enriching ExperienceMelani Feijoo HuangNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 Summary ZKDocument1 pageChapter 5 Summary ZKZeynep KeskinNo ratings yet

- L3 U01A Planet FootballDocument4 pagesL3 U01A Planet FootballsimonettixNo ratings yet

- Listening and Speaking MegacitiesDocument7 pagesListening and Speaking MegacitiesTania Melissa Chahcinoy GuanchaNo ratings yet

- Punctuation - Full StopDocument3 pagesPunctuation - Full StopHadassah PhillipNo ratings yet

- Intelligence and Second Language LearningDocument10 pagesIntelligence and Second Language LearningVirginia Alejandra GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Roger HawkeyDocument33 pagesRoger HawkeyAna TheMonsterNo ratings yet

- Language Varieties and Standard LanguageDocument9 pagesLanguage Varieties and Standard LanguageEduardoNo ratings yet

- Common European Framework of Reference For LanguagesDocument9 pagesCommon European Framework of Reference For LanguagesBruno FilettoNo ratings yet

- Reading ComprehensionDocument4 pagesReading Comprehensiondurgasaraswathi9111100% (1)

- Unit 3 Clipping Affixation Borrowing Blending and Stress Shift2Document6 pagesUnit 3 Clipping Affixation Borrowing Blending and Stress Shift2Kristian Marlowe OleNo ratings yet

- Top Notch vs. InterchangeDocument6 pagesTop Notch vs. InterchangegmesonescasNo ratings yet

- Giáo Trình Translation 2Document57 pagesGiáo Trình Translation 2Quỳnh PhươngNo ratings yet

- Aspects of Connected SpeechDocument2 pagesAspects of Connected SpeechstereoladNo ratings yet

- 'That' in Noun ClausesDocument3 pages'That' in Noun ClausesAbdulkadir BaştanNo ratings yet

- Questions 1 (Recuperado Automáticamente)Document4 pagesQuestions 1 (Recuperado Automáticamente)ximenaNo ratings yet

- Birth Order Reading ComprehensionDocument2 pagesBirth Order Reading Comprehensionjoseline tomala marinNo ratings yet

- Differences Between New Year Eve in Viet Nam and AmericaDocument2 pagesDifferences Between New Year Eve in Viet Nam and AmericaNgọc Hân Huỳnh PhạmNo ratings yet

- Unit 6B (2) : at Your ServiceDocument20 pagesUnit 6B (2) : at Your ServiceHuy Nguyễn Phan TrườngNo ratings yet

- 1C Global English Worksheet Answers ScriptDocument3 pages1C Global English Worksheet Answers ScriptEdmira Salčinović100% (1)

- Task Based Learning Factors For Communication and Grammar UseDocument9 pagesTask Based Learning Factors For Communication and Grammar UseThanh LêNo ratings yet

- Summary Chapter 4Document3 pagesSummary Chapter 4Hoàng VyNo ratings yet

- PPP Vs TBLDocument2 pagesPPP Vs TBLAndreas GavaliasNo ratings yet

- A Vietnamese - American Cross-Cultural Study of Conversational DistancesDocument53 pagesA Vietnamese - American Cross-Cultural Study of Conversational DistanceslehuulocNo ratings yet

- CA Sample End Term Test 2016Document3 pagesCA Sample End Term Test 2016KimLiênNguyễnNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Using Youtube Videos in Learning English Listening For English Majored Students at TDMUDocument4 pagesThe Effect of Using Youtube Videos in Learning English Listening For English Majored Students at TDMUTrinh NgocNo ratings yet

- Assessing VocabularyDocument12 pagesAssessing Vocabularyloveheart_112No ratings yet

- Cohesive Features in Argumentative Writing Produced by Chinese UndergraduatesDocument14 pagesCohesive Features in Argumentative Writing Produced by Chinese UndergraduateserikaNo ratings yet

- Pronunciation and Word StressDocument12 pagesPronunciation and Word StressPeter PatsisNo ratings yet

- Integrated Skills TestDocument9 pagesIntegrated Skills TestharonNo ratings yet

- Listening Insights For TKT CourseDocument14 pagesListening Insights For TKT CourseFrancisco Ricardo Chavez NolascoNo ratings yet

- Development of First and Secondlanguage Vocabulary Knowledge Among Languageminority Children Evidence From Single Language and Conceptual ScoresDocument12 pagesDevelopment of First and Secondlanguage Vocabulary Knowledge Among Languageminority Children Evidence From Single Language and Conceptual ScoresEric YeNo ratings yet

- Individual Differences in Early Language Learning - Final Author VersionDocument18 pagesIndividual Differences in Early Language Learning - Final Author VersionFeby LestariNo ratings yet

- Paradis Jia 2017 Bilingual OutcomesDocument16 pagesParadis Jia 2017 Bilingual OutcomesMonakaNo ratings yet

- First Lesson Plan TastingDocument3 pagesFirst Lesson Plan Tastingapi-316704749No ratings yet

- Pythagoras 3 (Solutions)Document5 pagesPythagoras 3 (Solutions)ٍZaahir AliNo ratings yet

- Practical TestDocument2 pagesPractical TestgolmatolNo ratings yet

- SEMINAR 08 Agreement and DisagreementDocument5 pagesSEMINAR 08 Agreement and Disagreementdragomir_emilia92No ratings yet

- Public History: Final Reflective EssayDocument12 pagesPublic History: Final Reflective EssayAngela J. SmithNo ratings yet

- The - Skillful - Teacher - CHP 3 To 6Document16 pagesThe - Skillful - Teacher - CHP 3 To 6Mummy Masayu100% (2)

- LP Math 1 2023Document4 pagesLP Math 1 2023Ma. Fatima MarceloNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 8623Document23 pagesUnit 4 8623Eeman AhmedNo ratings yet

- 6th Semester Final Result May 2021Document39 pages6th Semester Final Result May 2021sajal sanatanNo ratings yet

- Chapter1 Entrepreneurship NidhiDocument23 pagesChapter1 Entrepreneurship Nidhiusmanvirkmultan100% (3)

- Statistical Information (Institute - Wise)Document4 pagesStatistical Information (Institute - Wise)ShoaibAhmedKhanNo ratings yet

- Application For Revaluation/Scrutiny/Photocopy of V Semester Cbcss Degree Exams November 2020Document3 pagesApplication For Revaluation/Scrutiny/Photocopy of V Semester Cbcss Degree Exams November 2020Myself GamerNo ratings yet

- Soci1002 Unit 8 - 20200828Document12 pagesSoci1002 Unit 8 - 20200828YvanNo ratings yet

- Amaiub WBLDocument8 pagesAmaiub WBLGear Arellano IINo ratings yet

- A Comparative Essay On Ellen GoodmanDocument3 pagesA Comparative Essay On Ellen GoodmanSharn0% (2)

- SCIENCE 5e's Lesson Plan About DistanceDocument7 pagesSCIENCE 5e's Lesson Plan About DistanceZALVIE FERNANDO UNTUANo ratings yet

- Vidhan Bubna - Final ResumeDocument2 pagesVidhan Bubna - Final ResumeVidhan BubnaNo ratings yet

- Opinion Essay - Would You Be Ready To Live AbroadDocument2 pagesOpinion Essay - Would You Be Ready To Live Abroadali bettaniNo ratings yet

- LE Comon Machine TroublesDocument6 pagesLE Comon Machine TroublesCatherine Joy De Chavez100% (1)

- Engineering CET Brochure 2009 Final-09022009Document52 pagesEngineering CET Brochure 2009 Final-09022009Anil G. DangeNo ratings yet

- SIP Vision SharingDocument14 pagesSIP Vision SharingMarcela RamosNo ratings yet

- Greek Philosophy: A Brief Description of Socrates, Plato, and AristotleDocument3 pagesGreek Philosophy: A Brief Description of Socrates, Plato, and AristotleMissDangNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Span of ControlDocument2 pagesCase Study On Span of Controlsheel_shaliniNo ratings yet

- Assignment in Chilldren's LiteratureDocument4 pagesAssignment in Chilldren's LiteraturePrince LouNo ratings yet

- 2024 Fudan University Shanghai Government Scholarship For Foreign Students Application NoticeDocument2 pages2024 Fudan University Shanghai Government Scholarship For Foreign Students Application NoticeToni MengNo ratings yet