Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Barillo Vs Gervacio

Uploaded by

Prin CessOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Barillo Vs Gervacio

Uploaded by

Prin CessCopyright:

Available Formats

Barillo vs Gervacio FACTS: Barillo, as President of Cebu State, a government-owned educational institution, introduced a school-based entrepreneurship project known

as the Printing Entrepreneurial Shop (PES), installing himself as the Chairman and Hinoguin, Rojas, Plaza and Allego as the Project Coordinator, Project-in-Charge, Treasurer and Auditor, respectively. In order to establish the PES, seed money in the amount of P40,000.00 was obtained from the Cebu State Entrepreneurship Training Center (ETC) Funds purportedly as a loan to the PES. For this purpose, Rojas, as PES representative, and Eustiquio C. Alinabo, as Fund Administrator of the ETC, executed a Memorandum of Understanding dated September 2, 1994, which was approved by Barillo. The PES was thus formally established. It accepted printing jobs from Cebu State as well as other private entities. Meanwhile, the funds initially deposited in the account of ETC were subsequently withdrawn by Barillo, Rojas and Plaza and deposited in their joint account in Banco de Oro. Similarly, all the subsequent income and funds generated from the PESs operations were deposited in this joint account. In the course of the post-audit and verification of the accounts and operations of Cebu State, COA (Auditor Dela Pea) uncovered certain irregularities and anomalous transactions in relation to the operations of the PES. Auditor Dela Pea requested from Barillo a Value for Money Audit (VFM). Barillo denied the request. Based on the foregoing, Auditor Dela Pea executed an Affidavit accusing Barillo, Hinoguin, Rojas, Plaza and Allego, of violating the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act and the Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees (Code of Conduct). Auditor Dela Pea alleged that the expenditures for the PES projects were illegally taken from the General Fund of Cebu State and that the income generated therefrom were illegally funneled to the personal accounts of petitioners. Criminal case for violation of Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act was filed with the Sandiganbayan and Administrative case for dishonesty Ombudsman-Visayas. The criminal case was subsequently dismissed. Petitioners contention: due to the dismissal by the Sandiganbayan of Criminal Case, the administrative case for Dishonesty should similarly be dismissed. Petitioners also assail the Order directing them to immediately cease and desist from holding office as a palpable violation of the Constitution. According to them, while the Ombudsman has authority to file and investigate administrative cases against government officials and employees, the power to implement the decision of dismissal lies in the Office of the President or the Department Head. On the first issue. WON the Ombudsman has the authority to determine

the administrative liability of a public official or employee, and to direct and compel the head of the office or agency concerned to implement the penalty imposed. HELD: YES, the authority of the Ombudsman under Sec. 15 of Republic Act No. 6770 (RA 6770), otherwise known as The Ombudsman Act of 1989, to recommend the removal, suspension, demotion, fine, censure, or prosecution of an erring public officer or employee is not merely advisory but is actually mandatory within the bounds of the law, such that the refusal, without just cause, of any officer to comply with an order of the Ombudsman to penalize an erring public officer or employee is a ground for disciplinary action.

Second Issue: WON the acquittal of the petitioners in the criminal case results in the dismissal of the administrative case. HELD: NO, Administrative cases are, as a rule, independent from criminal proceedings. The dismissal of a criminal case on the ground of insufficiency of evidence or the acquittal of an accused who is also a respondent in an administrative case does not necessarily foreclose the administrative proceeding nor carry with it relief from administrative liability. This is because unlike in criminal cases which require proof beyond reasonable doubt, the quantum of proof required in administrative proceedings is substantial evidence, defined as such relevant evidence as a reasonable mind might accept as adequate to support a conclusion. Third Issue: WON petitioners are guilty of dishonesty. HELD: YES, Dishonesty connotes a disposition to lie, cheat, deceive, or defraud; unworthiness; lack of integrity; lack of honesty, probity or integrity in principle; lack of fairness and straightforwardness; disposition to defraud, deceive or betray. Notably, the Ombudsman and the Court of Appeals found that the ETC Funds were not meant to be lent as capital for entrepreneurial projects. They were purposely given to Cebu State in order to facilitate the establishment of the latters ETC. Barillo, as President of Cebu State, is charged with knowledge of this fact. Despite this knowledge, however, he approved the Memorandum of Understanding by virtue of which the PES obtained a loan of P40,000.00 from the ETC Funds. Worse, the proceeds of the loan, as well as the income generated by the PES from its operations, were deposited in the Banco de Oro account of Barillo, Rojas and Plaza. Moreover, there is a clear irregularity in the dealings between the PES and Cebu State in that Barillo, who acted as Chairman of the PES, was also the one who approved the latters printing contracts with Cebu State. Considering that he and the other petitioners have a pecuniary interest in the PES as they shared in its income, this conflict of interest should have been militantly guarded against.

There is therefore substantial evidence to find petitioners guilty of Dishonesty under the Code of Conduct. Their act of obtaining direct pecuniary benefits from the PES; use of Cebu States resources, manpower and facilities; disregard of their public accountability; and refusal to submit the books and accounts of the PES to audit are highly irregular and questionable.

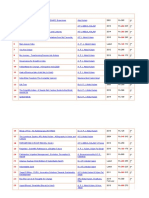

You might also like

- New Central Bank CASES No. 7 & 8Document3 pagesNew Central Bank CASES No. 7 & 8Kristian Oliver CebrianNo ratings yet

- 2008 DigestsDocument11 pages2008 Digestsdodong123No ratings yet

- Vitriolo V DasigDocument9 pagesVitriolo V DasigClement del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Barcena Case Digests Pub CorpDocument7 pagesBarcena Case Digests Pub CorpBryan Jayson BarcenaNo ratings yet

- FRIA Case DigestsDocument20 pagesFRIA Case Digestsnoorlaw75% (4)

- Complainants Vs Vs Respondent de Guzman Venturanza & Vitriolo Law OfficesDocument8 pagesComplainants Vs Vs Respondent de Guzman Venturanza & Vitriolo Law OfficesMonicaSumangaNo ratings yet

- Japson Vs CSC (Digest)Document3 pagesJapson Vs CSC (Digest)Louie Raotraot100% (3)

- Tala Realty Services Corporation Vs CADocument15 pagesTala Realty Services Corporation Vs CALyceum LawlibraryNo ratings yet

- Vitriolo vs. DasigDocument8 pagesVitriolo vs. Dasigroyel arabejoNo ratings yet

- (2-2) Vitriolo - v. - Dasig CANON 1Document8 pages(2-2) Vitriolo - v. - Dasig CANON 1Jinnelyn LiNo ratings yet

- Sesbreno vs. CADocument5 pagesSesbreno vs. CALyNne OpenaNo ratings yet

- Labor 2 M1&2 DigestDocument59 pagesLabor 2 M1&2 Digestrussel leah mae malupengNo ratings yet

- Digest AdminlawDocument17 pagesDigest AdminlawRaineNo ratings yet

- Ejercito V SandiganbayanDocument3 pagesEjercito V SandiganbayanMickey RodentNo ratings yet

- Speccom Exam DungayagenesisDocument11 pagesSpeccom Exam DungayagenesisRowena DumalnosNo ratings yet

- Banking DigestsDocument9 pagesBanking DigestsEm DavidNo ratings yet

- Corporation CasesDocument31 pagesCorporation CasesbgladNo ratings yet

- Banking Law Case DigestDocument4 pagesBanking Law Case DigestLiezel BabadNo ratings yet

- Concepcion, CJ: Entitlement To Constitutional Guarantee Stonehill v. DioknoDocument32 pagesConcepcion, CJ: Entitlement To Constitutional Guarantee Stonehill v. DioknoAnonymous jfDeg87No ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument7 pagesCase Digestronaldsatorre.15No ratings yet

- PoliRev State ImmunityDocument64 pagesPoliRev State ImmunityARIEL LIOADNo ratings yet

- Beja Sr. v. CADocument7 pagesBeja Sr. v. CAJose Antonio BarrosoNo ratings yet

- Case Digest Pimentel Vs Attys. Llorente & SalayonDocument2 pagesCase Digest Pimentel Vs Attys. Llorente & SalayonMadel Malone-Cervantes100% (1)

- PABLICO MASTERS PAB Vs CERRO JR. ET AL G.R. No. 200434Document4 pagesPABLICO MASTERS PAB Vs CERRO JR. ET AL G.R. No. 200434sayNo ratings yet

- Vitriolo v. DasigDocument9 pagesVitriolo v. DasigMaya Angelique JajallaNo ratings yet

- 7 - ABAKADA GURO PARTY LIST vs. PurisimaDocument15 pages7 - ABAKADA GURO PARTY LIST vs. PurisimafloravielcasternoboplazoNo ratings yet

- JudicialDocument34 pagesJudicialLenette LupacNo ratings yet

- Abakada vs. PurisimaDocument32 pagesAbakada vs. PurisimaRommel P. AbasNo ratings yet

- Olaguer Vs Regional Trial Court, 170 SCRA 478 Case Digest (Administrative Law)Document2 pagesOlaguer Vs Regional Trial Court, 170 SCRA 478 Case Digest (Administrative Law)AizaFerrerEbina100% (2)

- Balangauan Vs Court of Appeals, 562 SCRA 184 Case Digest (Administrative Law)Document2 pagesBalangauan Vs Court of Appeals, 562 SCRA 184 Case Digest (Administrative Law)AizaFerrerEbina67% (6)

- PALE - Agno - Vs - CagatanDocument3 pagesPALE - Agno - Vs - CagatanCamille RegalaNo ratings yet

- GBL 9 Soriano V PeopleDocument14 pagesGBL 9 Soriano V PeopleCol. McCoyNo ratings yet

- BSB GROUP V GODocument4 pagesBSB GROUP V GOALEXA100% (2)

- Insurance Case DigestDocument4 pagesInsurance Case DigestChristen HerceNo ratings yet

- AbakadaGuro Party List v. Purisima, 562 SCRA 251 (2008)Document31 pagesAbakadaGuro Party List v. Purisima, 562 SCRA 251 (2008)Enrique Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- PALE Case Digest AssignmentDocument20 pagesPALE Case Digest AssignmentDiana ConstantinoNo ratings yet

- ART XI, ConstitutionDocument6 pagesART XI, ConstitutionJosiebethAzueloNo ratings yet

- V.2 Poli-Digests-5 To 7-MaiDocument6 pagesV.2 Poli-Digests-5 To 7-MaiMyla RodrigoNo ratings yet

- Abakada Guro v. Purisima, G.R. No. 166715, August 14, 2008. Full TextDocument20 pagesAbakada Guro v. Purisima, G.R. No. 166715, August 14, 2008. Full TextRyuzaki HidekiNo ratings yet

- Bouncing Check & Bank Secrecy LawDocument19 pagesBouncing Check & Bank Secrecy LawDave A Valcarcel0% (1)

- ASsignment-3-Admin (1) April 15Document54 pagesASsignment-3-Admin (1) April 15balmond miyaNo ratings yet

- Republic v. CuadernoDocument2 pagesRepublic v. CuadernoMaria Olivia Repulda AtilloNo ratings yet

- Justice Bernabe Case Digests, AteneoDocument274 pagesJustice Bernabe Case Digests, AteneoAiren Jamirah Realista PatarlasNo ratings yet

- 03-Sps. Yu v. Atty. Palaña A.C. No. 7747 July 14, 2008Document4 pages03-Sps. Yu v. Atty. Palaña A.C. No. 7747 July 14, 2008Jopan SJNo ratings yet

- Galicto V AquinoDocument3 pagesGalicto V AquinoEpibelle EderNo ratings yet

- 13 - G.R. No. 166715Document26 pages13 - G.R. No. 166715masterlazarusNo ratings yet

- 16 Letter - of - Atty. - Cecilio - Y. - Arevalo - JR PDFDocument4 pages16 Letter - of - Atty. - Cecilio - Y. - Arevalo - JR PDFCeresjudicataNo ratings yet

- Gonzaga v. CoaDocument2 pagesGonzaga v. CoaAlamMoBa?No ratings yet

- B.M. No. 1370Document3 pagesB.M. No. 1370emmanuel fernandezNo ratings yet

- Petitioners: en BancDocument52 pagesPetitioners: en BancCarol TumanengNo ratings yet

- Poli. 4E Digests. MidtermsDocument72 pagesPoli. 4E Digests. MidtermsCat VGNo ratings yet

- 13 Former Assistant Prosecutor Barrozo DigestDocument2 pages13 Former Assistant Prosecutor Barrozo DigestRexNo ratings yet

- Sasan V NLRCDocument3 pagesSasan V NLRCAices Salvador100% (2)

- BM 1370Document3 pagesBM 1370ERNIL L BAWANo ratings yet

- Debt CollectionDocument4 pagesDebt CollectionLM RioNo ratings yet

- Constitution Statutes Executive Issuances Judicial Issuances Other Issuances Jurisprudence International Legal Resources AUSL ExclusiveDocument11 pagesConstitution Statutes Executive Issuances Judicial Issuances Other Issuances Jurisprudence International Legal Resources AUSL Exclusivekikhay11No ratings yet

- Commercial Law Banking CasesDocument4 pagesCommercial Law Banking CasesAhmad AbduljalilNo ratings yet

- Canon 7 9 CasesandDigestsDocument92 pagesCanon 7 9 CasesandDigestsdNo ratings yet

- Daduvo vs. CSC, 223 Scra 747Document6 pagesDaduvo vs. CSC, 223 Scra 747JemNo ratings yet

- Legal Words You Should Know: Over 1,000 Essential Terms to Understand Contracts, Wills, and the Legal SystemFrom EverandLegal Words You Should Know: Over 1,000 Essential Terms to Understand Contracts, Wills, and the Legal SystemRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (16)

- Econ 2Document3 pagesEcon 2Prin CessNo ratings yet

- Department of Labor and EmploymentDocument6 pagesDepartment of Labor and EmploymentPrin CessNo ratings yet

- Forms Anscc PresentationDocument10 pagesForms Anscc PresentationPrin CessNo ratings yet

- Historical Background of EconomicsDocument3 pagesHistorical Background of EconomicsPrin Cess100% (3)

- Pre-Trial in Criminal CasesDocument3 pagesPre-Trial in Criminal CasesPrin CessNo ratings yet

- EconDocument2 pagesEconPrin CessNo ratings yet

- Legforms 1Document0 pagesLegforms 1Prin CessNo ratings yet

- Corporation Law Q&ADocument6 pagesCorporation Law Q&APrin CessNo ratings yet

- Labor 1Document24 pagesLabor 1Prin CessNo ratings yet

- Rem Rev IDocument45 pagesRem Rev IPrin CessNo ratings yet

- FORMS 3rd PartyDocument8 pagesFORMS 3rd PartyPrin CessNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure Rules 1 - 71 Limitations of The Rule-Making Power of The Supreme CourtDocument16 pagesCivil Procedure Rules 1 - 71 Limitations of The Rule-Making Power of The Supreme CourtPrin CessNo ratings yet

- Us V Panlilio - DigestDocument1 pageUs V Panlilio - DigestPrin CessNo ratings yet

- Final SpecproDocument78 pagesFinal SpecproPrin CessNo ratings yet

- Property 1Document7 pagesProperty 1Prin CessNo ratings yet

- Digest LPODocument5 pagesDigest LPOPrin CessNo ratings yet

- Corporation Law Q&ADocument6 pagesCorporation Law Q&APrin CessNo ratings yet

- Property FullDocument23 pagesProperty FullPrin CessNo ratings yet

- Velasquez v. Solidbank Corp. (2006)Document4 pagesVelasquez v. Solidbank Corp. (2006)Prin CessNo ratings yet

- Corporation Law Q&ADocument6 pagesCorporation Law Q&APrin CessNo ratings yet

- Corporation Law Q&ADocument6 pagesCorporation Law Q&APrin CessNo ratings yet

- Module1 Student ExercisesDocument21 pagesModule1 Student ExercisesPrin CessNo ratings yet

- Katarungang PambarangayDocument6 pagesKatarungang PambarangayPrin CessNo ratings yet

- PaleDocument10 pagesPalePrin CessNo ratings yet

- Prop 2Document7 pagesProp 2Prin CessNo ratings yet

- Prop 2Document6 pagesProp 2Prin CessNo ratings yet

- La Bugal Case.Document3 pagesLa Bugal Case.Karen GinaNo ratings yet

- Reflection On Sumilao CaseDocument3 pagesReflection On Sumilao CaseGyrsyl Jaisa GuerreroNo ratings yet

- Logic of English - Spelling Rules PDFDocument3 pagesLogic of English - Spelling Rules PDFRavinder Kumar80% (15)

- Harvard ReferencingDocument7 pagesHarvard ReferencingSaw MichaelNo ratings yet

- Sample Financial PlanDocument38 pagesSample Financial PlanPatrick IlaoNo ratings yet

- TN Vision 2023 PDFDocument68 pagesTN Vision 2023 PDFRajanbabu100% (1)

- EDCA PresentationDocument31 pagesEDCA PresentationToche DoceNo ratings yet

- Pediatric ECG Survival Guide - 2nd - May 2019Document27 pagesPediatric ECG Survival Guide - 2nd - May 2019Marcos Chusin MontesdeocaNo ratings yet

- Intro To EthicsDocument4 pagesIntro To EthicsChris Jay RamosNo ratings yet

- Karnu: Gbaya People's Secondary Resistance InspirerDocument5 pagesKarnu: Gbaya People's Secondary Resistance InspirerInayet HadiNo ratings yet

- Entrenamiento 3412HTDocument1,092 pagesEntrenamiento 3412HTWuagner Montoya100% (5)

- Physiology PharmacologyDocument126 pagesPhysiology PharmacologyuneedlesNo ratings yet

- Sample A: For Exchange Students: Student's NameDocument1 pageSample A: For Exchange Students: Student's NameSarah AuliaNo ratings yet

- KalamDocument8 pagesKalamRohitKumarSahuNo ratings yet

- DLP No. 10 - Literary and Academic WritingDocument2 pagesDLP No. 10 - Literary and Academic WritingPam Lordan83% (12)

- Seminar On DirectingDocument22 pagesSeminar On DirectingChinchu MohanNo ratings yet

- The BreakupDocument22 pagesThe BreakupAllison CreaghNo ratings yet

- A Professional Ethical Analysis - Mumleyr 022817 0344cst 1Document40 pagesA Professional Ethical Analysis - Mumleyr 022817 0344cst 1Syed Aquib AbbasNo ratings yet

- CAPE Env. Science 2012 U1 P2Document9 pagesCAPE Env. Science 2012 U1 P2Christina FrancisNo ratings yet

- SEW Products OverviewDocument24 pagesSEW Products OverviewSerdar Aksoy100% (1)

- Magnetic Effect of Current 1Document11 pagesMagnetic Effect of Current 1Radhika GargNo ratings yet

- Imogen Powerpoint DesignDocument29 pagesImogen Powerpoint DesignArthur100% (1)

- Sayyid DynastyDocument19 pagesSayyid DynastyAdnanNo ratings yet

- Abramson, Glenda (Ed.) - Oxford Book of Hebrew Short Stories (Oxford, 1996) PDFDocument424 pagesAbramson, Glenda (Ed.) - Oxford Book of Hebrew Short Stories (Oxford, 1996) PDFptalus100% (2)

- DMSCO Log Book Vol.25 1947Document49 pagesDMSCO Log Book Vol.25 1947Des Moines University Archives and Rare Book RoomNo ratings yet

- Buddhism & Tantra YogaDocument2 pagesBuddhism & Tantra Yoganelubogatu9364No ratings yet

- 2017 - The Science and Technology of Flexible PackagingDocument1 page2017 - The Science and Technology of Flexible PackagingDaryl ChianNo ratings yet

- SULTANS OF SWING - Dire Straits (Impresión)Document1 pageSULTANS OF SWING - Dire Straits (Impresión)fabio.mattos.tkd100% (1)

- Outline - Criminal Law - RamirezDocument28 pagesOutline - Criminal Law - RamirezgiannaNo ratings yet

- Organizational Behavior (Perception & Individual Decision Making)Document23 pagesOrganizational Behavior (Perception & Individual Decision Making)Irfan ur RehmanNo ratings yet

- Purposeful Activity in Psychiatric Rehabilitation: Is Neurogenesis A Key Player?Document6 pagesPurposeful Activity in Psychiatric Rehabilitation: Is Neurogenesis A Key Player?Utiru UtiruNo ratings yet