Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Prison Experiences of The Suffragettes in Edwardian Britain

Uploaded by

Felis_Demulcta_MitisOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Prison Experiences of The Suffragettes in Edwardian Britain

Uploaded by

Felis_Demulcta_MitisCopyright:

Available Formats

This article was downloaded by: [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] On: 17 April 2013, At: 07:32 Publisher:

Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Women's History Review

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rwhr20

The prison experiences of the suffragettes in Edwardian Britain

June Purvis

a a

University of Portsmouth, United Kingdom Version of record first published: 20 Dec 2006.

To cite this article: June Purvis (1995): The prison experiences of the suffragettes in Edwardian Britain, Women's History Review, 4:1, 103-133 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09612029500200073

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN Womens History Review, Volume 4, Number 1, 1995

The Prison Experiences of the Suffragettes in Edwardian Britain

JUNE PURVIS University of Portsmouth, United Kingdom

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

ABSTRACT This article focuses in depth upon the prison experiences of the suffragettes in Edwardian Britain and challenges many of the assumptions that have commonly been made about women suffrage prisoners. Thus it is revealed that a number of the prisoners were poor and working-class women and not, as has been too readily assumed, bourgeois women. The assumption too that the women prisoners were single is challenged. Married women and mothers as well as spinsters, endured the harshness of prison life. Other differences between the women, such as disability and age, are also explored. Despite such differentiation, however, the women prisoners developed supportive networks, a culture of sharing and an emphasis upon the collectivity. Their courage, bravery and faith in the womens cause, especially when enduring the torture of forcible feeding and repeated imprisonments, should remain an inspiration to all feminists today.

The womens movement of early Edwardian Britain has attracted the attention of many scholars.[1] In particular, most of the interest has focused on the militant [2] suffragettes, especially those active within the Womens Social and Political Union (WSPU), founded on 10 October 1903 by Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst and her eldest daughter, Christabel. Yet, as Liz Stanley and Ann Morley point out, the WSPU was not a single entity; on the level of practical feminist politics, the formal dividing barriers between the WSPU and other suffrage organisations such as the Womens Freedom League (WFL), the National Union of Womens Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), the United Suffragists (US) and the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF) often broke down.[3] From 1905 until the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 about 1000 women were sent to prison because of their suffrage activities, most of these being members of the WSPU and of the less militant WFL.[4] While these prison experiences have not been ignored by historians, they have been discussed as a part of a broader account of the suffrage movement rather than focused upon in depth as a

103

JUNE PURVIS

subject worthy of investigation.[5] Furthermore, a dominant narrative of these experiences has emerged which has only recently been challenged by some Second Wave feminist historians. In this dominant narrative, we may identify two main themes. First, that the women themselves were to blame for their often harsh prison experiences, including the pain of hunger striking and forcible feeding, and secondly, that the prisoners were middle-class and single women. Early histories of the suffrage movement present a more sympathetic picture of prison life than many subsequent accounts. Metcalfe, for example, writing in 1917, speaks of the scenes of horror which had taken place in Holloway and other prisons ... in the unavailing effort to govern women against their consent.[6] However, it is the history written by the constitutional suffragist, Ray Strachey, a member of the NUWSS and hostile to the WSPU, that became the influential text. Strachey blames the WSPU women themselves for the treatment they received from the prison authorities with what Dodd has termed illiberal callousness.[7] Unwilling to acknowledge the hunger strike as a political tool, Strachey comments how the suffragettes, once in prison, ceased to be militant and created a number of protests including the refusal to eat food. Forcible feeding was tried in vain, she continues; the prisoners struggled so violently against it that the process became actually dangerous, and the prison officials were obliged to let them starve till they came to the edge of physical collapse, and then to let them go.[8] In spite of the severe pain and damage to health which the process involved, scores of suffragettes adopted it ... The officials tried everything they could think of in vain ....[9] This picture of irrational women, deliberately seeking their own torture was eagerly seized upon by male historians who sought to ridicule the WSPU and its politics. George Dangerfields The Strange Death of Liberal England, first published in 1935, discusses the suffragette movement as one of the forces in the downfall of the Liberal Party.[10] Describing the movement as a form of pre-war lesbianism of daring ladies, he suggests that the best way to approach the campaign for womens emancipation is through the wardrobe.[11] Thus we find references to high starched collars, hard straw hats, long skirts, feathered hats and corseted bosoms.[12] Not surprisingly, Dangerfield too presents the suffragettes as fanatical women who chose the hardships of prison life in a sado-masochistic way ... How can one avoid the thought, he questions, that they sought these sufferings with an enraptured, a positively unhealthy pleasure?[13] If the victim does not resist, forcible feeding is no more than extremely unpleasant. But the suffragettes were determined to resist.[14] In view of the fact that Dangerfields account contained no footnotes whatsoever to primary sources to support his claims, it is incredulous that his analysis was received so enthusiastically and became so influential. The Times and Tribune, for example, hailed it as brilliant.[15] Reprinted, at least up to 1972, it

104

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

presented a narrative and historical plot from which, as Jane Marcus observes, subsequent historians have seldom been able to free themselves; as the first historian, that is male historian, to treat the womens movement seriously, Dangerfield was assured of frequent citation.[16] Thus the scene of the drama is set and the props are changed only with slight variations. Roger Fulford in 1957 emphasised the middle-class membership of the WSPU and mocked their prison experiences, claiming that solitary confinement in prison was not always unwelcome to adults.[17] Furthermore, although forcible feeding is a disgusting topic ... it was not dangerous ... [It] is of course a familiar form of treatment in lunatic asylums.[18] While Andrew Rosen is much more sympathetic to the women prisoners, he too, in a matter of fact way speaks of how forcible feeding involved mouths being prised open, lacerations, phlegm, vomiting, pain in various organs, loss of weight and so on.[19] David Mitchell compares the WSPU to the German terrorist Baader-Meinhof Gang and suggests that like the prison staffs which had to deal with writhing WSPU militants, German doctors were sometimes sorely tempted to let their charges die of hunger if they wished.[20] Martin Pugh contends that the WSPU, by driving the Liberals to force-feeding and the Cat and Mouse Act (Figure 1), hoped to discredit the government totally in the eyes of its supporters.[21] Brian Harrison, while admiring the injudicious courage with which respectable Edwardian middle-class women undertook militancy, facetiously points out that clumsiness in the prison-doctor during forcible feeding could destroy womans greatest assets, her looks which were necessary for what was then seen as her most important trade, marriage.[22] And Les Garner, while noting that from April 1913 until the outbreak of the First World War Mrs Pankhurst was in and out of prison like a yo-yo imprisoned and released ten times, nevertheless adds, If nothing else, suffragette militancy destroyed the myths about the physical capabilities of women.[23] This dominant narrative was not always challenged in the new feminist womens history that was written after the advent of the Second Wave of feminism in Britain, Western Europe and the USA from the late 1960s. In particular, in Britain, it was particularly socialist feminists who were active in researching womens past. And as socialists for whom capitalism, not patriarchy, was the key source of womens oppression, the WSPU was easily dismissed as a bourgeois movement that failed to attract working-class women and to support working-class causes. Sheila Rowbotham, for example, whose 1973 book, Hidden from History: 300 years of womens oppression and the fight against, is commonly regarded as the catalyst for the growth of feminist history in Britain, criticises Mrs Pankhurst and Christabel for not thinking of mobilising women workers to strike, but of making even more dramatic gestures.[24] The Pankhursts, she asserts, minus the socialist daughter Sylvia, were quite explicitly on the

105

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

JUNE PURVIS

side of the ruling class, conservatism and the Empire ... The split was apparent when Sylvias attempt to link the womens cause to that of the working class met with her mothers and her sisters determined opposition.[25] This theme, that the only significant form of struggle is that against class exploitation was especially evident in Liddington & Norriss account of the involvement of working-class women in radical suffragist politics in early twentieth-century Lancashire.[26] Although condemning the Liberal governments cruel treatment of the WSPU prisoners, the WSPU is identified with Mrs Pankhurst and Christabel and presented as a bourgeois organisation that during 1906 lost the support of working-class women.[27]

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

121mm

Figure 1. WSPU poster for the The Cat and Mouse Act of 1913 (see note [21])

Critics of this analysis have not been plentiful in Britain, the most sustained voice being that of the radical feminists Stanley and Morley, who explore the way the Union operated as a feminist organisation through womens friendship networks; furthermore, they emphasise that the WSPU

106

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

campaigned for an end to a wide range of social ills that particularly affected working women, such as sweated labour, low pay, womens and childrens sexual slavery, and was thus feminist socialist in orientation.[28] Apart from their contribution, it has largely been left to US based feminist historians to present an alternative picture to the dominant paradigm discussed above. Thus Martha Vicinus offers an insightful analysis of the way the suffragettes believed that only by giving their bodies to the womens cause through such public activities as marching in delegations or processions, selling literature, public speaking and ultimately, for many, the physical sacrifice of prison and hunger striking would they win the necessary spiritual victory that would enable them to enter the male political world.[29] Marcus, in contrast, interprets the hunger strike as a symbolic refusal of motherhood since when woman, as the quintessential nurturer, refuses to eat she cannot nurture the nation.[30] Mary Jean Corbett argues further that by denying their prescribed reproductive function, suffragette hunger-strikers were contesting patriarchal definitions of woman-as-mother while also appropriating what had been the political tool of other, mostly male, dissenters to make their own argument.[31] All of these feminist histories, however, as well as more recent accounts of the suffrage movement in Scotland and Wales, stress the middle-class membership of the WSPU.[32] Furthermore, none of these accounts, like those considered previously, focus in detail on prison life. The aim of this article is to address this neglect. In particular, by drawing upon a range of personal texts written by the suffrage prisoners themselves, such as published autobiographies, unpublished and published letters and unpublished and published testimonies, I shall reveal aspects of the prison experience that have remained hidden from view.[33] I shall focus especially, although not exclusively, on WSPU women.

ooo

Although prison conditions might vary, depending on the year in which the sentence was served and upon local variations and personnel, common admission procedures stripped the individual of self-identification. On entry to Holloway in 1908, for example, the women were immediately called to silence by the wardresses, locked in reception cells, and then sent to the doctor before they were ordered to undress. Once they had been searched to make sure they concealed nothing, their own clothes were stored by the authorities and details requested about name, address, age, religion and profession and whether she could read, write and sew. A bath was then taken. Although each bather was separated from the next by a partition, low doors enabled wardresses to overlook such a private bodily function. Once dried, the prisoner was told to dress herself from clothes lying in piles on

107

JUNE PURVIS

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

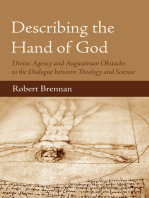

the floor. Second-class prisoners wore green serge dresses, third-class brown. All had white caps, blue and white check aprons, and one big blue and white handkerchief a week. Every garment was branded in several places, black on light things, white on dark, with a broad arrow. Underclothing was coarse and ill-fitting; shoes were heavy and clumsy and rarely in pairs while the black thick and shapeless stockings, with red stripes going round the legs, had no garters or suspenders to keep them up. On the way to her cell, the prisoner was given sheets for the bed, a toothbrush (if she asked for it), a Bible, prayer book and hymn book, a small book on Fresh Air and Cleanliness and a tract entitled The Narrow Way. Once in the cell, which might be about 9 feet high and either about 13 feet by 7 feet or 10 feet by 6 feet (Figure 2), she was given a yellow badge bearing the number of her cell and the letter and number of its block in the prison. From now until her release, the inmate would be known only by her cells number.[34]

124mm

108

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN Figure 2. A cell in Holloway Prison, similar to those occupied by the suffragettes, as it is in the daytime, with the plank bed against the wall and the bedding folded up. Source: Supplement to the Illustrated London News, 7 August 1909.

Prison regulations imposed a certain routine on daily life.[35] At this period in Holloway, for example, a waking up bell rang about 5.30, one and three-quarter hours before a breakfast consisting of a pint of sweet tea, a small brown loaf and two ounces of butter (which had to last all day) was handed to the prisoner in her cell. Before the daily half an hour of chapel the prisoner had to empty her slops, scrub the floor and three planks that formed her bedstead, fold up the bedclothes into a roll and stow them away with the mattress and pillow, and polish with soap and bath-brick the tin utensils of her cell. Inspection each day ensured that the task was done in the required manner. In chapel and at the daily hour of exercise in a gravelled yard, talking was not permitted. Lunch was at noon and a supper consisting of a pint of cocoa with thick grease on top plus a small brown loaf was taken at 5pm. The electric light in the cell was controlled from outside and turned off at 8 in the evening. During the first 4 weeks of imprisonment, the rest of the prisoners time was spent in her cell, which was often airless, especially in summer; a certain amount of associated labour had to be undertaken, which might involve making nightgowns or knitting mens socks. Once a week a bath was taken and twice a week books could be borrowed from the poorly stocked prison library. After 4 weeks, prisoners were allowed to take their needlework or knitting to the hall downstairs, which was more airy, and sit side by side, although talking was still forbidden. Those serving one month or less in the Second Division were not entitled to receive any visits from friends nor to have any correspondence with them. Special permission to visit might sometimes be obtained by making special application to the Home Office or through a Member of Parliament. Those whose sentences exceeded a month were entitled to a visit at the end of a month, and on that occasion not more than three friends were allowed to see the prisoner. The prisoner was also entitled to write a letter at the end of a months imprisonment, for which writing materials, in addition to the slates and slate pencils given on admission, were permitted.[36] A reply to that letter might be sent to the prison and then given to the prisoner. While all suffragette prisoners shared with other women inmates this structuring of their daily lives (even though the formal rules were frequently subverted), their differential status was also apparent. Since it was commonly recognised that the militants did not belong to the so-called criminal classes[37], they were usually segregated from the other women by being placed in separate cell blocks and being kept separate in communal activities, such as chapel and exercise. Often too, they were placed in the newer, lighter cells, as Maud Joachim found when she entered Holloway Gaol in 1908 but this was not always so.[38] Katherine Gatty, of the WFL, in the same jail 4 years later was initially placed in E Block which was

109

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

JUNE PURVIS

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

ghastly! The lavatory accommodation was absolutely inadequate. The whole block was infested with mice & co. there was no heating apparatus at all. Her relief was enormous when, during the month of March, she was transferred to another block. Im all right now in D, she wrote to Mrs Arney.[39] Mary Nesbitt was another Holloway prisoner in 1912 who found her cell unacceptable. On one of its dirty walls had been written Thank God I am going out in two days had a month for soliciting in Hyde Park. Refusing to stay in a room that had been occupied by a prostitute, her request for a transfer was given without delay.[40] The hierarchy between different categories of prisoner was also evident in the practice of Third Division women cleaning the cells of those who, for various reasons, were exempted from doing so. Sylvia Pankhurst, placed in a hospital cell in 1913, exhausted and ill after being forcibly fed, remembered how Third Division prisoners scrubbed her cell floor old women: pale women: a bright young girl who smiled at me whenever she raised her eyes from the floor; a poor, ugly creature without a nose, awful to look up.[41] Such contacts often highlighted for the suffragettes the common bond between all womankind and how they had to work not just for the vote but for a wider range of issues, including prison reform. The sweet and innocent-looking face of one prison cleaner, just over 20 years of age, made an impression on the young Greta Cameron, condemned to a punishment cell for desiring fresh air. When Greta quietly asked the cleaner what crime she had committed, the reply of attempted suicide! so horrified the WSPU member that she resolved to work for prison reform, after the needful tool of the vote was won.[42] Above all else, however, the recognition of the suffragettes as not ordinary inmates was marked by their collective belief in The Cause, a theme that was articulated by WSPU leaders and rank and file members alike. Emmeline Pankhurst, the much loved leader of the WSPU, implored in 1909:

Women! Comrades! Dear Fellow-workers! I charge you, love this Movement, work for it, live for it. Let no thought of your own comfort and happiness hinder you from rendering it your whole service. Give it your thought, your time, your all. It is worth everything that you can give.[43]

For Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, treasurer of the WSPU and one of its leaders until ousted by Mrs Pankhurst and Christabel in 1912, women of the upper, middle and working classes found a new comradeship with each other in the suffrage cause. Neither class, nor wealth, nor education counted any more, she claimed, only devotion to the common ideal.[44] Although by 1912, when the more extreme forms of militancy were common, there was a marked decline in the rate of new members joining the WSPU[45], time and time again suffragette prisoners testified that they endured the hardships of prison life because they believed in the womens

110

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

movement, the feeling of collectivity that was fostered, the common bond that united all women and the dignity of women to stand up and fight for what they believed in. Patricia Woodlock, honorary secretary of the Liverpool branch of the WSPU and imprisoned many times, did not hesitate to put the welfare of her sex before her own freedom.[46] Emily Wilding Davison, imprisoned eight times, stressed that the perfect militant warrior will sacrifice all ... to win the Pearl of Freedom for her sex.[47] Daisy Dorothea Solomon saw her prison life as a baptism to work for the uplifting of womanhood.[48] Ethel Smyth remembered with affection those women forgetful of everything save the idea for which they had faced imprisonment.[49] Kathleen Emerson, while serving her sentence in 1912, expressed her feelings in poetry:

THE WOMEN IN PRISON Oh, Holloway, grim Holloway, With grey, forbidding towers! Stern are they walls, but sterner still Is womans free, unconquered will. And though to-day and yesterday Brought long and lonely hours, Those hours spent in captivity Are stepping-stones to liberty.[50]

Mary Nesbitt, coming out of jail in the same year, emphasised, I was deeply impressed by the wonderful spirit of loyalty and love for the cause and for our leaders all, irrespective of class, creed or age, were unwavering.[51] For these women and many more, The Cause was like a religion and the participants a spiritual army who sought a new way of life.[52] As Elizabeth Robins, the well-known actress, writer and WSPU member commented, the ideal for which Woman Suffrage stands has come, through suffering, to be a religion. No other faith held in the civilised world to-day counts so many adherents ready to suffer so much for their faiths sake.[53] This faith in the movement helped the forging of a community spirit and supportive networks amongst the women prisoners so that they were, what one WSPU member termed a sympathetic family helping each other to endure.[54] Various activities organised by the prisoners both expressed this sense of belonging and helped to maintain it. In Holloway in 1912, on a chilly May morning in the exercise yard, the women played Here we come gathering nuts and may on a cold and frosty morning with Mrs Pankhurst and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence joining in the game.[55] Football was played too, and with especial vigour by Emily Wilding Davison who became very hot and tired.[56] Various entertainments, such as singing, story telling and reading aloud, also took place.[57] Even a sports day was held, complete with prizes, and considered by Margaret Thompson as more enjoyable than Vera Wentworths impersonation, with a button in her eye, of Lord Cromer.[58] A scene from Shakespeares The Merchant of Venice was

111

JUNE PURVIS

performed, with Miss Grey as the Duke, Hilda Burkett as Shylock, Doreen Allen as Narissa, Mrs Field as Gratiano, Miss Mitchell as Antonia, and Mrs Bard as Bassanio.[59] All suffrage prisoners, including those who were members of the WFL, joined in the activities. Katherine Gatty, a League member friendly with Emily Wilding Davison, observed that her fellow prisoners played everything imaginable, like a lot of small children & sometimes so roughly that now & again someone gets rather badly hurt, with a sprained wrist or ankle. Furthermore:

One day we had that was rather pretty & very clever a Fancy Dress Ball. The girl who put on a brown paper hat & folded her arms like Napoleon, was most clever ... Another day we had a contested general election, using our slates as sandwich men. The candidates (four girls) were chained the aged electors ... we carried to the poll. The ... speeches, the election addresses, the canvassing & (I regret to say) the bribery & corruption were all realistic![60]

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

The group cohesion and emotional support so evident in these activities could also extend to the many ways the formal rules were broken by, for example, hiding written notes in stockings and passing them secretly to each other in church services on Sundays.[61] The knowledge that WSPU members outside were sending thoughts of comfort and also demonstrating in a more noisy way around or near the prison walls reinforced the sense of solidarity. In her address at the weekly At Home of the WSPU at Queens Hall on Monday 6 November 1908, for example, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence announced that a fresh demonstration on a larger scale than previously would be made to Holloway the following Saturday. Singers, sellers and sewers wanted!, she pleaded the singers to form a choir, the sellers to distribute suffrage literature and the sewers to make some imitation prison clothes for released prisoners to wear.[62] Such demonstrations, with bands playing The March of the Women and the crowd singing The Marseillaise could be very cheering to the lonely suffragette prisoner, locked in her cell at night.[63] Indeed, as Mrs Marie Leigh, a working-class woman from Birmingham and the first suffragette to be forcibly fed, pointed out, it was all the Heart beats, thoughts & love which were just concentrated on us from outside that enabled us to Hold on Hold fast & Hold Out.[64] However, despite the sense of unity and friendship the suffragettes felt as they faced the common external reality of prison life, their shared experiences were not experienced equally but fractured on a number of differences. This is not surprising given the complexity of womens lives within a radical womens political movement that was both in opposition to, and yet a part of, an Edwardian culture that expected women to be ideally located within the private sphere of the home rather than the male world of politics. Differences would also be accentuated by the fact that hunger striking and force feeding were acts committed by, and on, individuals in

112

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

their own cells. Whether force fed by a cup, tube through the nostril (the most common method) or tube down the throat into the stomach (the most painful), the individual suffragette struggled on her own and often feared damage to the mind or body. Kitty Marions screaming in prison greatly upset the other women, but she found it was the only way she could fight against the torture of forcible feeding and remain sane.[65] Rachel Peace, an embroideress, who had already experienced several nervous breakdowns, was not so fortunate. During a period of prolonged hunger striking and forcible feeding three times a day she feared, I should go mad ... Old distressing symptoms have re-appeared. I have frightful dreams and am struggling with mad people half the night.[66] Her fears became true when she lost her reason in prison and spent the rest of her life in and out of asylums, with Lady Constance Lytton, an upper-middle-class WSPU worker, maintaining her.[67] The forcible feeding of the disabled May Billinghurst in Holloway in January 1913 brought a particular wave of revulsion since she was small, frail, and ha[d] been a cripple all her life.[68] Paralysed as a child and confined to a tricycle for mobility[69], she told how the three doctors and five wardresses who held her down:

forced a tube up my nostril; it was frightful agony, as my nostril is small. I coughed it up so that it didnt go down my throat. They then were going to try the other nostril, which, I believe is a little deformed. They forced my mouth open with an iron instrument, and poured some food into my mouth. They pinched my nose and throat to make me swallow.[70]

After 10 days of almost incredible suffering, when she was fed three times every 24 hours, she was released a physical wreck.[71] Margaret Thompson, in prison in 1912, had a facial disability, resulting from a car accident; after examining her face to see if it was fit for forcible feeding, the doctor decided she should be fed by the cup rather than the tube.[72] Miss McCrae, in prison at the same time, thought she too should take food through the cup, on account of her deafness, although she feared the other women would scorn her for doing so.[73] For women with disabilities such as those mentioned here, imprisonment and forcible feeding were particular acts of courage. Age, too, would be another possible line of difference. The three grandmothers, Mrs Heward, Mrs Boyd and Mrs Aldham, in Holloway in 1912, as well as the 78 year-old Mrs Brackenbury, may have found prison life especially tiring.[74] And older women generally may have been more prone to accidents. A tall suffragette, by no means young, tripped and fell in a frosty exercise yard one morning and broke several bones although this was not discovered until the day before her sentence expired.[75] It is highly probable that few teenagers became prisoners since Mrs Pankhurst had an inflexible rule that no one under 21 years old should do anything that might incur a prison sentence.[76] Nevertheless, there were a number of

113

JUNE PURVIS

women prisoners in their mid-twenties and thirties who may have had more energy and agility than their more mature sisters. However, those women still menstruating may have found their monthly cycle an inconvenience, especially when the supply of sanitary towels was inadequate. Phyllis Keller, in Holloway in 1912, found none available and so her mother sent to her some of the old fashioned, washable sort while also using the opportunity to hide in the box a small ball with which the women would play.[77] Despite the importance of such factors as age and disability in fracturing prison experiences, personal accounts written by suffragette prisoners reveal that the most commonly recorded differences related to marital status, social class background and rank within the WSPU. It is commonly assumed that the majority of suffragette prisoners were single rather than married women.[78] Of the 108 women arrested for stone throwing after a demonstration to the House of Commons on 29 June 1909, for example, 80 were termed Miss and 26 Mrs.[79] Yet there were, as we shall see, a number of married prisoners too, often with children, although it is difficult to quantify their number. However, whether married or not, the women were not separated from their lives outside the prison: the sexual politics of home, work and politics could intermesh with prison life in complex yet different ways.[80] Single women may have worried about employers, parents, friends and lovers, and some might have had dependants. The 80 single women arrested and imprisoned for stone throwing on 29 June, included a number engaged in paid work Miss Ivy Beach and Nellie Godfrey were both business women; Sarah Carwin, Helen Grace Lenanton, Rachael Graham and Ellen Pitman were nurses; Millicent L. Brown, Alice E. Burton, Emily Wilding Davison, Florence T. Down, Elizabeth Roberts, Irene Spong and Alice M. Walters were teachers; Kitty Marion an actress; Katheleen Streatfield an artist; Jessica Walker a portrait and landscape painter; and Harriet Rozier a typical working woman, having had to earn her bread since she was nine years old.[81] Employers may not have looked kindly upon such behaviour, especially when it involved the inconvenience of absenteeism. Florence T. Down, for example, was a supply teacher in the elementary sector and had 2 days pay withheld from her when her case was adjourned, a loss she could barely afford since she was the eldest of seven at that time and a great deal depended on me.[82] Elementary schoolteachers, of course, were particularly vulnerable to hostility since their salaries were paid out of public funds.[83] Elsa Myers, a London County Council teacher somewhere in North London, arranged to be arrested on the last day of the summer term in order to keep her militant activity unknown to the authority. Thus she spent her summer vacation in jail and was released in time ready for the start of the new term.[84] Kitty Marion, the actress, could find that even one night in a cell, resulting in one missed performance, was sufficient to damage chances of future employment; the one member of the AFL who

114

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

was repeatedly arrested and imprisoned, she was eventually forced to give up her theatrical career.[85] And countless more single women faced a range of other personal issues, including the pressure to hide their true identity under a fictitious name. Agnes Olive Beamish, for example, along with Elsie Duval, was sentenced to 6 weeks imprisonment in April 1913 for being a suspected person or reputed thief when, both having lost their way in the early hours of the morning, they were arrested on the street in possession of paraffin and other incendiary materials carried in suitcases. Olive was convicted under the name of Phyllis Brady.[86] Worries about dependants and parents must also have been common for single women. Dora Montefiore, a widow, found the visit of her daughter who was pregnant with her first child and far from strong a bitter-sweet experience. I could not bear that she should see me, her mother, in prison dress, wrote Dora in her autobiography.[87] She worried, too, about how she could send money to her son who was entirely dependent upon her financially for his engineering studies:

The end of the month was approaching, and I had had one or two sleepless nights in prison wondering how I should send him his allowance which was due at the end of the month, and wishing at the same time I might be able to send him a message of love and of sorrow for the trouble I knew I was causing him by the publicity of my actions.[88]

When Miss Charlotte Marsh was serving a 3 month prison sentence in Winson Green Prison in 1909, during which she was tube-fed 139 times, her father became dangerously ill. Although the prison authorities knew of his illness, they did not release Charlotte until 9 December, one day after they received the news that he was dying. Travelling straight to Newcastle by train, she found her father unconscious. He died without recognising her.[89] Alison Neilans, of the WFL, planning a hunger strike, smuggled out a note to Edith How-Martyn in December of the same year. I have decided on the All, she confessed, & have commenced the secret fast today Monday 27th. She implored her friend not to worry nor to enquire about her, unless she became ill. Dont tell Mother yet, was another plea, but let Peter know.[90] It was probably the rare suffragette and yet there were some who felt that she had no one to worry about and no one to worry over her. Such circumstances, as with Mary Richardson, may have helped the unmarried WSPU member to become one of the more militant guerrilla activists, engaging in bombing empty buildings and in arson:

What brought me some relief, personally, was the knowledge I belonged nowhere; I had no home, and so there was nobody who would worry over me and over whom I need worry. From the start it had been this knowledge that had made me feel I must do more than my fair share to make up for the many women who stood back from militancy because 115

JUNE PURVIS

of the sorrow their actions would have caused some loved one. It would have been the same with me had I been in their position. For anyone who loved me to have suffered on my account would have been an unbearable thing.[91]

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

Contrary to the popular view[92], a number of married women did enter prison, although not always under their married name. Mrs Frances Clara Barlett, for example, conscious of her husbands position, decided to serve her months imprisonment as Frances Satterley, her maiden name.[93] Wives and mothers, especially those with small children, were likely to be anxious about how their families coped in their absence. Minnie Baldock, a WSPU organiser and wife of a fitter in Canning Town, was sentenced to one months imprisonment in February 1908. Her anxieties about her small son, left at home with his father, might be somewhat alleviated by the knowledge that Union members outside would offer help. Julie Easts invitation to Minnies husband to bring the boy over to her one Sunday so she could have lent him books & known more that he liked was not realised, however, since Mr Baldock was unable to come and Julie East herself had been very poorly.[94] Maud Arncliffe Sennett, on the other hand, a relatively wealthy Union member, sent the child some presents much to his delight:

Dear Lady Thank you very much for the toys you sent me. I am proud of my mother. I will be glad when She comes out of prison But I now [sic] She is there for a good cause. I am saving up all my farthings to put in that money box you was kind enough to send me. I will send it on as soon as I get it full. For the cause. I am writing this letter with your nibs you sent me. Again thanking you for sending me so many nice presents which amuse me very much. I remain greatfully [sic] yours J. Baldock.[95]

Mrs Baldock, like other working-class women, would not be able to afford to pay for alternative child care while she was in jail and would have to rely on the goodwill of her husband and neighbours. But even when a prisoner did have domestic help at home, the worries about the family were still acute. A typical example is that of Myra Sadd Brown writing to her husband from Holloway on 16 March 1912. She had discovered in her bag a photograph of her children and now kissed them every night and was glad that they were always looking at her. Let them know a little where I am so that they can send their loving thoughts to me, she pleaded, they need not think because I am shut up I have done wrong. When she got into her narrow bed at night her thoughts however flew to her husband & your strong loving arms.[96] Her undated letter to her children and Mademoiselle,

116

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

written on dark brown lavatory paper, probably 6 days later, is especially poignant:

My three little Darlings & Mlle Mummy thanks you ever so much & also Mlle for the letters they were such a joy & I wanted to kiss them all over but I am going to kiss all the writers when I see them & I dont think there will be much left when I have finished. I have got such a funny little bed, which I can turn right up to the wall when I dont use it. I am learning French & German so you must work well or Mummy will know lots more than you. Next time you see Granny I want you to give her a big kiss and hug from me with lots of love Now 1. 2. & 3 it is Mummys bed time so goodnight ... Lots of love & kisses Mummy Mrs Pankhurst thinks there is enough evidence against her to give her 7 years. Dont forget Matildas bedstead.[97]

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

Some weeks earlier, on 24 February 1912, Mrs Alice Singer, married with two small daughters, Mary and Christabel, had written to the WSPU offices to offer herself as a window breaker. After she committed the deed, she was arrested. On 2 March 1912, while at Bow Street Police Station, she wrote to her husband and youngest child, Mary, Perhaps you will not see me for some weeks. That is why I thought I would write. She also worried about Mrs Lane, who sat next to her and whose boys & Tom Rowat are so proud of her; but Col. Lane is very angry. She entreated her family to try to alleviate the tensions in the Lane household. You must cheer the boys up; & perhaps you, Daddy, can make their Daddy more reasonable.[98] Another window breakerr, Mrs Hudleston, serving 6 months in Birmingham Gaol, developed excessive anxiety at being separated from her small daughter who had developed tubercular glands, which might need an operation. The anxious parent petitioned the Home Office for release on condition of being bound over for a reasonable period, and was told that the petition would only be granted if she consented to be bound over for life.[99] As all these accounts by single and married women reveal, prison life could be interwoven with a range of duties as wage or salary earners, daughters, friends, wives and mothers. It is commonly assumed that suffragettes were middle-class women, the educated and well-to-do.[100] Obviously working-class women, especially in comparison with leisured middle- and upper-class women, would have less time and money to give to The Cause. Hannah Mitchell, a working-class wife and mother and member of the WSPU in its early years, travelled down from Manchester to join the demonstration to the House of Commons on 23 October 1906. Coming back home on the midnight train, tired and

117

JUNE PURVIS

exhausted, she knew that arrears of work, including the weekly wash awaited her return. Working housewives, she mused, faced with such an accumulation of tasks, often resolved never to leave home again.[101] Yet despite such difficulties, a number of poor WSPU women, like Minnie Baldock, served prison sentences. Indeed, even by 1912, 9 years after the WSPU was founded, Ethel Smyth found in Holloway more than a hundred women, rich and poor ... young professional women ... countless poor women of the working class, nurses, typists, shop girls, and the like.[102] These working-class women would have to rub shoulders with their more elevated sisters, such as Miss Janie Allan, a millionairess of the Allan Line, Lord Kitcheners niece Miss Parker, several cousins of Lord Haigs, Mrs Barbara Ayrton Gould (daughter of Hertha Ayrton, the scientist who invented the safety lamp for miners) and Alice Morgan Wright, an American sculptress.[103] The official line of the prison authorities was that all prisoners were treated alike, irrespective of their class background, a claim of which some in the WSPU became very suspicious. Lady Constance Lytton, an upper-middle-class spinster, believed she had received preferential treatment in Newcastle Prison when, on hunger strike in October 1909, she was not forcibly fed and released after only 2 days, officially because of her heart condition. Although Constance did indeed have a weak heart and had been, in her own words, more or less of a chronic invalid throughout the great part of her youth [104], she felt that her family background and political connections (her brother was the Earl of Lytton and a member of the House of Lords) had influenced the prison authorities; lesser known women and women in poorer health than she had been imprisoned longer and forcibly fed. An incident later in the year confirmed her doubts. On 21 December, Selina Martin, a working-class woman of high character [105], was arrested and remanded for a week in Walton Gaol, Liverpool, bail being turned down. Refusing to eat prison food, she and another working-class woman, Leslie Hall, were forcibly fed despite the fact that it was contrary to the law for remand prisoners to be treated in this way. After being kept in chains at night, Selina was frog-marched up the steps to a cell where she was forcibly fed again. Since frog-marching involved seizing her arms and legs and carrying her head downwards, her head bumped on each step. The brutality of the incident was reported in many of the major newspapers and on the front page of the 7 January 1910 issue of Votes for Women. Constance, in Manchester at the time, shared her concerns with a distressed Mary Gawthorpe, another Union worker, who confided that the women were quite unknown nobody knows or cares about them except their own friends. They go to prison again and again to be treated like this, until it kills them! Constance determined to try out whether the prison authorities would recognise her need for exceptional favours if they did not know her name.[106] Thus, after some elaborate planning, including

118

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

removing her own initials from her underwear, she assumed the guise of Jane Warton, a working woman, and rejoined the WSPU under her new name. With her hair cut short and parted in early Victorian fashion, a tweed hat with a bit of tape saying Votes for Women interlaced with the hatband, woollen scarf and gloves, a pair of pince-nez spectacles, and small china portrait brooches of Mrs Pankhurst, Mrs Pethick-Lawrence and Christabel Pankhurst pinned to the collar of a long green coat costing 8s. and 6d, Jane Warton protested against forcible feeding outside Walton Gaol and was arrested.[107] Sentenced to a fortnight in the Third Division, she went on a hunger strike.

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

140mm

Figure 3. A WSPU poster reproduced in Votes for Women, October 1909, p. 68.

119

JUNE PURVIS

Before the first forcible feeding, neither her heart was examined nor her pulse felt. After a struggle, the doctor managed to insert a steel gag which fastened her jaws wide apart, far more than they could go naturally, and caused intense pain. Then:

he put down my throat a tube which seemed to me much too wide and was something like four feet in length. The irritation of the tube was excessive. I choked the moment it touched my throat until it had got down. Then the food was poured in quickly; it made me sick a few seconds after it was down and the action of the sickness made my body and legs double up, but the wardresses instantly pressed back my head and the doctor leant on my knees. The horror of it was more than I can describe. I was sick over the doctor and wardresses, and it seemed a long time before they took the tube out. As the doctor left me he gave me a slap on the cheek, not violently, but as it were, to express his contemptuous disapproval.[108]

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

This scene was repeated another seven times before Constances true identity was discovered and she was released. Although she had proved her point about the differential prison treatment of women from differing social backgrounds, she never fully recovered from her ordeal, but suffered a stroke in 1912 and died in 1923. Social class differences between women prisoners were also apparent not just in the different ways they were treated by the prison authorities but in the differing class experiences and expectations of the women themselves. The new prisoner, Zo Proctor, expected her bed to be made for her, much to the amusement of the old-timers around her.[109] Margaret Thompson, on her first imprisonment in February 1909, found that:

The scrubbing of my floor was a new experience. I was toiling away at it when a wardress came and looked on disapprovingly. What have you been doing to the floor of your cell, 27? I have been attempting to scrub it, I answered. I think it is an attempt was the sneering reply. Then she showed me how to wring out the flannel and remarked You must do it better another time.[110]

A parlour maid in Holloway with Margaret at this time, Miss Walsh, may not have needed such instruction. She seemed to keep to herself ... and was conscious ... of not always knowing what good form was, and that kept her quiet and retiring.[111] Class differences between women prisoners may have become more accentuated after 15 March 1910 when Rule 243a was added to the regulations governing prison life. The new rule, framed with the suffragettes in mind, permitted the Secretary of State to approve ameliorations ... in respect of the wearing of prison clothing, bathing, hair-curling, cleaning of cells, employment, exercise, books, and otherwise.[112] Under the new rule, the wealthy Miss Allen was always correctly dressed for prison exercise,

120

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

and wore a hat and lemon kid gloves.[113] Under the new rule too, friends and relatives outside, could send in extra food. Phyllis Keller asked her mother to send parcels of fruit and a hamper with enough for three meals twice a week; on the other days she would eat prison food.[114] The potential of such gifts for splintering the sense of collectivity amongst the inmates was mitigated by the practice of those militants outside organising money collections for prisoners hampers and of those inside sharing any food that was sent in. In 1912, for example, Mrs A. E. Gordon of 16 Daleham Gardens, Hampstead, thanked those who had sent money in response to her appeal for funds for prisoners hampers. Those who gave money included Mrs M. Pollock, 10s; Miss Evelyn Sharp, 1.1s; Miss A. Clifford, 1s 6d; Mrs Saul Soloman, 10s 6d; and Miss Morice, 2s.[115] In Holloway in June 1912, Margaret Thompson went round distributing much praised shortbread while Miss Allan put cake, strawberries and cherries on her plate.[116] The arrival of another parcel from Ilkley, this time containing pressed beef and a large veal roll, was also shared.[117] It was at this time, too, that the suffragette prisoners had another lesson in the ways the prison authorities could offer preferential treatment to certain of their members, on this occasion according to their rank within the WSPU. When Mrs Pankhurst, and Emmeline and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence were sentenced on 22 May 1912 to 9 months in the Second Division, they had all proclaimed their intention of hunger striking unless they were accorded the normal rights of political offenders and transferred to the First Division. Five days after their removal there, on 15 June, the WSPU held a meeting at the Albert Hall where Mabel Tuke announced that if the government did not transfer all 75 WSPU members currently in prison also to the First Division, all, including the leaders, would hunger strike.[118] The audience cheered when she told them that messages from the prisoners in Holloway, Winson Green Prison, Birmingham, and Aylesbury Prison, would now be read out. The sense of collectivity that the WSPU inspired amongst its members was typically expressed by the Winson Green prisoners:

Give our love to all our friends, and tell them we long to join them in their strenuous work out-side. Meanwhile, we are playing our part with undaunted spirits. Our hearts go out in love and sympathy to our brave leaders, and we are ready to face whatever lies before us and fight with all our strength to win for them and for all who come after us the status of political offenders.[119]

When the Government refused to transfer all suffragette prisoners to the First Division, the threatened hunger strike began on 19 June. Frederick Pethick-Lawrence was force fed five times, his wife once. Mrs Pankhurst, lying in bed, very weak from starvation, was in the cell next to Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence when she heard a sudden scream come from her friend and then the sound of a prolonged and very violent struggle. I sprang out

121

JUNE PURVIS

of bed, Mrs Pankhurst recalled in her autobiography, and, shaking with weakness and with anger, I set my back against the wall and waited for what might come.[120] When the doctors and wardressess appeared at her door, she grabbed a heavy earthenware water jug on a nearby table and cried, If any of you dares so much as to take one step inside this cell I shall defend myself. The group retreated.[121] By 6 July, all the hunger strikers had been released, including 545 women who were freed before their sentences had expired.[122] This was the last attempt made by the prison authorities to forcibly feed Emmeline Pankhurst. The Government was too worried about her possible death on their hands, and thus instant martyr status, to dare attempt such an assault again.[123] Unlike well-connected women and high-ranking women within the WSPU who might receive privileged prison treatment, unknown and occasionally well-known women from the rank and file shared alike, irrespective of their social class background, the torture of forcible feeding. As we saw earlier, the first woman to be forcibly fed, in October 1909, was a rank and file member from Lancashire, a working woman of sturdy constitution, Mrs Marie or Mary Leigh.[124] Nurse Ellen Pitfield, also forcibly fed in 1909, was a poorly paid midwife.[125] In the summer of 1914, Mary Richardson, a relatively unknown middle-class woman who had achieved notoriety by slashing the painting of the Robeky Venus in the National Gallery earlier in the year, was a mouse on an expired licence, evading arrest, when she was caught and convicted of arson. Back in Holloway, she was too tired and dejected to offer any resistance physical or mental to the first attempt to forcibly feed her.[126] Afterwards, lying exhausted on her bed, she could barely acknowledge her old cleaner who bent over her, the smell of the dirty water in her bucket making Mary feel nauseous. The following week, when some of Marys strength returned and she resisted the forcible feeding with almost superhuman strength, sterner tactics were used. In a ju-jitsu hold, a small wardress threw her to the floor and then immobilised her by burrowing her thumbs into Marys neck and drawing the pointed end of a large key up and down the soles of her stockinged feet. Thus utterly passive, prostrate and amenable, the only difficulty the doctors encountered was forcing the stiff end of the tube into her swollen nostril.[127] For many of these women, the worst feature of prison life was the public violation of their bodies when being forcibly fed. Helen Gordon Liddle hated the lack of privacy when enduring the pain of forced feeding.[128] Nell Hall spoke of the frightful indignity of it all.[129] For Sylvia Pankhurst, the sense of degradation endured was worse than the pain of sore and bleeding gums, with bits of loose jagged flesh, the agony of coughing up the tube three or four times before it was successfully inserted, the bruising of her shoulders and the aching of her back.[130] Sometimes,

122

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

when the struggle was over, or even in the heat of it, she felt as though she was broken up into many different selves, of which one, aloof and calm, surveyed all the misery, and one, ruthless and unswerving, forced the weak, shrinking body to its ordeal. Although the word rape is not used in the personal accounts of force fed victims, the instrumental invasion of the body, accompanied by overpowering physical force, great suffering and humiliation was akin to it [131], especially so for women fed through the rectum or vagina. Janet Arthur, later identified as Fanny Parker, in Perth prison in 1914, was one such victim:

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

Thursday morning, 16th July ... the three wardresses appeared again. One of them said that if I did not resist, she would send the others away and do what she had come to do as gently and as decently as possible. I consented. This was another attempt to feed me by the rectum, and was done in a cruel way, causing me great pain. She returned some time later and said she had something else to do. I took it to be another attempt to feed me in the same way, but it proved to be a grosser and more indecent outrage, which could have been done for no other purpose than torture. It was followed by soreness, which lasted for several days.[132]

When released, a medical examination revealed swelling and rawness in the genital region.[133] The knowledge that new tubes were not always available and that used tubes may have been previously inflicted on diseased persons and the mentally ill or be dirty inside the tube, issues that had been openly discussed in Votes for Women[134], undoubtedly added to the feelings of abuse, dirtiness and indecency that the women felt. On 10 August 1914, on the outbreak of the First World War, the Government ordered all persons serving prison sentences for suffrage agitation to be released.[135] Three days later, Mrs Pankhurst called an end to all militancy ... it has been decided to economise the Unions energies and financial resources by a temporary suspension of activities.[136] This news must have been greeted with mixed feelings by WSPU activists, glad that their guerrilla activities would end, sad at the prospect of slaughter that war would bring and disappointed that all their efforts had still not won the vote for women. Mary Richardson and other battle-worn suffragettes were delighted to see the last of the policemen and detectives as they were to see the last of them.[137] Elsie Bowerman greeted the declaration of war with almost a sense of relief ... as we knew that our militancy, which had reached an acute stage, could cease and we could devote ourselves entirely to the service of our country.[138]

ooo

123

JUNE PURVIS

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

This account of the prison experiences of the suffragettes in Edwardian Britain has revealed that historians have too readily assumed that the women were bourgeois. As we have seen, a focus on the suffrage prison experience offers an introduction to the poor, and not simply the working class. Furthermore, the common assumption that the women prisoners were single women is not valid. Mothers with children endured the harshness of prison life as well as single women. Despite these and other differences, however, the prisoners developed supportive networks and a culture of sharing. In particular, their insistence upon the collectivity holds an important lesson for feminists today. As they knew, to emphasise our differences at the expense of our commonalities, is to re-radicalise our politics and to weaken the potential alliances between all women. Their courage, bravery and faith, particularly when enduring the torture of forcible feeding and repeated imprisonments, remains an inspiration to us all. Acknowledgements I would like to thank the two referees for this journal who commented on previous drafts of this article which was accepted for publication in 1993. Any errors, however, remain my own. Some of the material presented here has been discussed in June Purvis (1994) Doing feminist womens history: researching the lives of women in the suffragette movement in Edwardian England, in Mary Maynard & June Purvis (Eds) Researching Womens Lives from a Feminist Perspective, pp. 166-189 (Basingstoke: Taylor & Francis). Notes

[1] See, for example, Ray Strachey (1928) The Cause, a short history of the womens movement in Great Britain (London: G. Bell & Sons); E. Sylvia Pankhurst (1931) The Suffragette Movement, an intimate account of persons and ideals (London: Longmans, Green & Co.); Roger Fulford (1957) Votes for Women, the story of a struggle (London: Faber & Faber); Christabel Pankhurst (1959) Unshackled, the story of how we won the vote (London: Hutchinson); Josephine Kamm (1966) Rapiers and Battleaxes, the womens movement and its aftermath (London: George Allen & Unwin); Constance Rover (1967) Womens Suffrage and Party Politics in Britain 1866-1914 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul); David Mitchell (1967) The Fighting Pankhursts, a study in tenacity (London: Jonathan Cape); Antonia Raeburn (1973) The Militant Suffragettes (London: Michael Joseph); Jill Liddington & Jill Norris (1978) One Hand Tied Behind Us, the rise of the womens suffrage movement (London: Virago); Brian Harrison (1978) Separate Spheres: the opposition to womens suffrage in Britain (London: Croom Helm; Martin Pugh (1990) Womens Suffrage in Britain 1867-1928 (London: The Historical Association, pamphlet); Leslie Parker Hume (1982) The National Union of Womens Suffrage Societies 1897-1914 (New York and London: Garland

124

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

Publishing); Brian Harrison (1982) The act of militancy, violence and the suffragettes, 1904-1914, in his Peaceable Kingdom, stability and change in modern Britain, pp. 26-81 (Oxford: Oxford University Press); Brian Harrison (1983) Womens suffrage at Westminster, 1866-1928, in Michael Bentley & John Stevenson (Eds) High and Low Politics in Modern Britain (Oxford: Oxford University Press); Les Garner (1984) Stepping Stones to Womens Liberty, feminist ideas in the womens suffrage movement 1900-1918 (London: Hutchinson); Sandra Stanley Holton (1986) Feminism and Democracy, womens suffrage and reform politics in Britain 1900-1918 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press); Susan Kingsley Kent (1987) Sex and Suffrage in Britain 1860-1914 (New Jersey: Princeton University Press); Lisa Tickner (1987) The Spectacle of Women, imagery of the suffrage campaign 1907-14 (London: Chatto & Windus); Jane Marcus (Ed.) (1987) Suffrage and the Pankhursts (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul); Linda Walker (1987) Party political women: a comparative study of Liberal women and the Primrose League, 1890-1914, in Jane Rendall (Ed.) Equal or Different, womens politics 1800-1914, pp. 165-191 (Oxford: Basil Blackwell); Liz Stanley with Ann Morley (1988) The Life and Death of Emily Wilding Davison: a biographical detective story (London: The Womens Press); Katrina Rolley (1990) Fashion, femininity and the fight for the vote, Art History, 13 March, pp. 47-71; Claire Hirshfield (1990) A fractured faith: Liberal Party women and the suffrage issue in Britain, 1892-1914, Gender and History, 2, pp. 173-197; Sandra Stanley Holton (1990) In sorrowful wrath; suffrage militancy and the romantic feminism of Emmeline Pankhurst, in Harold Smith (Ed.) British Feminism in the Twentieth Century, pp. 7-24 (Aldershot: Edward Elgar); Hilda Kean (1990) Deeds not Words: the lives of suffragette teachers (London: Pluto Press); Leah Leneman (1991) A Guid Cause, the womens suffrage movement in Scotland (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press); Rowena Fowler (1991) Why did suffragettes attack works of art? Journal of Womens History, 2, pp. 109-125; Kay Cook & Neil Evans (1991) The petty antics of the bell-ringing boisterous band? the womens suffrage movement in Wales, 1890-1918, in Angela John (Ed.) Our Mothers Land, chapters in Welsh womens history 1830-1939 (Cardiff: University of Wales Press); Janet Lyon (1992) Militant discourse, strange bedfellows: suffragettes and vorticists before the war, Differences: a Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, 4, pp. 100-133; Sandra Stanley Holton (1992) The suffragist and the average woman, Womens History Review, 1, pp. 9-24; June Purvis (1994) A lost dimension? The political education of women in the suffragette movement in Edwardian Britain, Gender and Education, 6, pp. 319-327; June Purvis (1995) Deeds, not words: the daily lives of militant WSPU suffragettes in Edwardian Britain, Womens Studies International Forum, 18, forthcoming. [2] The term militant is usually applied to the activities of members of the WSPU and constitutional to the law-abiding methods of the NUWSS, led by Mrs Millicent Garrett Fawcett. The analytical imprecision of these terms, however, is explored in Holton, Feminism and Democracy, p. 4, where she points out that if militancy involved a preparedness to resort to extreme forms of violence (such as arson, bombing and vandalising pillar boxes and large-scale 125

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

JUNE PURVIS

window-smashing raids) then few militants were militant and then only from 1912 onwards. If, as Holton argues, militancy concocted amongst NUWSS members a willingness to take the issues on to the streets, or if it sometimes indicted labour and socialist affiliations, then many constitutionalists were also militant. Similarly Purvis (1995) Deeds, not words, points out that to label all WSPU members militant is to ignore the differentiation within the WSPU; in particular, I suggest that we might apply the label militant to that small number of WSPU members who engaged in such activities as arson and window smashing and feminists to that much larger number of WSPU members who participated in peaceful activities, such as taking part in processions and demonstrations, selling newspapers, doing general office work. I am not adopting this terminology in this article, however, but, instead, follow the practice amongst historians of referring to WSPU and NUWSS members as suffragettes and suffragists, respectively. It is commonly believed that the term suffragette was coined by the Daily Mail in 1906 to describe WSPU activists see A. E. Metcalfe (1917) Womans Effort, a chronicle of British womens fifty years struggle for citizenship (1865-1914), p. 36 (Oxford: B. H. Blackwell), and Rosen, Rise Up Women!, p. 65. [3] Stanley with Morley, The Life and Death of Emily Wilding Davison, p. 175. [4] Figures are calculated from the Roll of Honour, Suffragette Prisoners 1905-1914 (n.d.) (Keighley: Rydal Press). It is impossible to be accurate here. I am assuming that those listed with female or male first names are, respectively, women and men. I have excluded from my count the 49 persons listed with a surname but no Christian name or initial. [5] For feminists, womens experiences have traditionally formed the bedrock of feminist knowledge and, in particular, their common experiences derived from their subordination under patriarchy. Thus finding womens voices in the past has been regarded as a critical concern for feminist historians who search for, and quote from, personal texts written by women, such as personal letters, diaries and autobiographies, as a way of documenting a womans experience. However, the term experience has recently been subjected to critical enquiry by post-structuralists, especially in the USA. For example, Joan Scott (1991) The evidence of experience, Critical Inquiry, 17, Summer, p. 797, points out that the historian cannot capture the lived reality of any one individual, a comment with which many historians would agree. Experience, she continues, is a linguistic event ... Experience is a subjects history. Language is the site of historys enactment (p. 793). Yet again, most historians would agree that language is necessary for both the subject of history and for the historian studying that subject to communicate his or her views. However, Scott then goes further in her argument and states that historians need to attend to the historical processes that, through discourse, position subjects and produce their experiences (p. 779). This notion that language/discourses produce experiences and the emphasis generally given by post-structuralists to the study of such phenomena rather than material reality has been strongly criticised by a number of feminists see, for example, the exchange between Joan Scott and Linda Gordon (1990) in Signs, 15, pp. 848-860; Kathleen 126

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

Canning (1994) Feminist history after the linguistic turn: historicizing discourse and experience, Signs, 19, pp. 368-404, and the critique of post-structuralism offered by Joan Hoff (1994) Gender as a postmodern category of paralysis, Womens History Review, 3, pp. 149-168. Ruth Roach Pierson (1991) Experience, difference, dominance and voice in the writing of Canadian womens history, in Karen Offen, Ruth Roach Pierson & Jane Rendall (Eds) Writing Womens History: international perspectives, pp. 79-106 (Basingstoke: Macmillan) offers some particularly useful reflections which have influenced my own views on the debate. Thus I argue that a suffragettes experience of prison life, as evident in the various texts documenting that experience, was not a mere abstraction or a discursive reality; to claim that it was would be to deny that woman a subjectivity from which to speak. Although any one text quoted in this article is not that suffragettes experience but a representation of it, it was a lived experience even if mediated through her material, social and interpersonal context as well as the discourses of the day. Thus any one prisoners experience would be both subject to and the subject of such phenomena something about which we cannot draw clear hard and fast distinctions. [6] Metcalfe, Womans Effort, p. 363. [7] Kathryn Dodd (1990) Cultural politics and womens historical writing: the case of Ray Stracheys The Cause, Womens Studies International Forum, 13, p. 135. [8] Strachey, The Cause, p. 314. [9] Ibid., p. 314. [10] George Dangerfield (1972 reprint edition) The Strange Death of Liberal England (London: Granada Publishing; first published 1935, London: McGibbon & Kee). The other forces include Tory rebellion over Home Rule for Ireland and the rise of organised labour. [11] Ibid., pp. 40, 135. [12] Ibid., p. 145. [13] Ibid., p. 145. [14] Ibid., p. 163. [15] Ibid., cited on the back cover. [16] Jane Marcus (1987) Introduction to Marcus (Ed.) Suffrage and the Pankhursts, pp. 2-3. [17] Fulford, Votes for Women, p. 176. [18] Ibid., p. 206, my emphasis. [19] Rosen, Rise Up Women!, p. 124. [20] David Mitchell (1977) Queen Christabel, a biography of Christabel Pankhurst, p. 322 (London: MacDonald & Janes). [21] Pugh, Womens Suffrage in Britain, p. 25, my emphasis. The Cat and Mouse Act is the popular term for the Prisoners Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health Act, rushed through Parliament in April 1913, which allowed prisoners who 127

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

JUNE PURVIS

had damaged their own health through their own conduct to be released into the community and then, once fit, to be re-arrested to continue their sentence. The Cat was the state and the Mouse the suffragette, clawed back at the wish of her tormentor. [22] Harrison, The act of militancy, p. 27. [23] Garner, Stepping Stones to Womens Liberty, p. 49, my emphasis. [24] Sheila Rowbotham (1973) Hidden from History: 300 years of womens oppression and the fight against it, p. 88 (London: Pluto Press). [25] Sheila Rowbotham (1975 reprint edition) Women, Resistance and Revolution p. 85 (Harmondsworth: Penguin; first published 1972, London: Allen Lane). [26] Liddington & Norris (1978) One Hand Tied Behind Us (London: Virago). See the insightful review by Christine Stansell (1983) One Hand Tied Behind Us: a review essay, in Judith L. Newton, Mary P. Ryan & Judith R. Walkowitz (Eds) Sex and Class in Womens History (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul). [27] Liddington & Norris, One Hand Tied Behind Us, p. 207. A similar viewpoint is evident in Gifford Lewis (1988) Eva Gore-Booth and Esther Roper (London: Pandora Press); although Gore-Booth and Roper were from upper-middle and middle-class backgrounds, respectively, their work in campaigning for improvements in the lives of working-class women is praised while the WSPU is seen as a narrow movement that excluded working-class women. [28] Stanley with Morley, The Life and Death of Emily Wilding Davison, p. 84. See also the sympathetic appraisals of the Pankhursts in Dale Spender (1982) Women of Ideas and What Men Have Done To Them: from Aphra Behn to Adrienne Rich, pp. 397-403 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul) and Elizabeth Sarah (1983) Christabel Pankhurst: reclaiming her power (1880-1958), in Dale Spender (Ed.) Feminist Theorists: three centuries of womens intellectual traditions, pp. 256-284 (London: The Womens Press). [29] Martha Vicinus (1985) Independent Women: work and community for single women 1850-1920, pp. 263, 268 (London: Virago). [30] Marcus, Introduction to her Suffrage and the Pankhursts, pp. 1-2. [31] Mary Jean Corbett (1992) Representing Femininity: middle-class subjectivity in Victorian and Edwardian womens autobiographies, p. 163 (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press). [32] Stanley with Morley, The Life and Death of Emily Wilding Davison, p. 85; Vicinus, Independent Women, p. 256; Marcus, Introduction to her edited Suffrage and the Pankhursts, p. 4; Corbettt, Representations of Femininity, p. 169; Leneman,A Guid Cause, pp. 93-94; Cook & Evans (1991) The petty antics of the bell-ringing boisterous band?, p. 159. [33] For a discussion of some of the factors that may have framed the way these texts were written and of the problems involved when consulting and interpreting such personal texts see Purvis, Doing feminist womens history, pp. 178-184. [34] Mrs Pankhurst (1908) Suffragists in prison, The Daily Telegraph, 18 February.

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

128

SUFFRAGETTES IN EDWARDIAN BRITAIN

[35] The following information is taken from Maud Joachim (1908) My Life in Holloway Gaol, Votes for Women, 1 October, pp. 4-5, and Daisy Dorothea Solomon (n.d. 1909?) My Prison Experiences, leaflet reprinted from the Christian Commonwealth, 25 August 1909. [36] The Times (1908) 18 November, House of Commons, Tuesday, 17 November. [37] Tickner, The Spectacle of Women, p. 107. [38] Joachim, My life in Holloway Gaol, p. 5. [39] Unpublished letter dated 14 March 1912 from Katherine Gatty in Holloway to Mrs Arney, Fawcett Library Autograph Letter Collection, London Guildhall University. [40] Unpublished letter dated 1 May 1912 from Mary C. Nesbitt to Miss Sinclair, Suffragette Fellowship Collection, Museum of London. [41] Pankhurst, The Suffragette Movement, p. 446. [42] Greta Cameron (1909) The spirit that upheld us, Votes for Women, 20 August, p. 108. [43] Emmeline Pankhurst (1909) March, breast forward!, Votes for Women, 2 July, p. 880. [44] Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence (1938) My Part in a Changing World, p. 188 (London: Victor Gollancz). [45] Rosen, Rise Up Women!, p. 211. [46] Patricia Woodlock procession and meeting, Votes for Women, 25 June 1909, p. 843. [47] Emily Wilding Davison (1914) The price of liberty, Daily Sketch, 28 May. [48] Solomon, My Prison Experiences, p. 7. [49] Ethel Smyth (1934) Female Pipings in Eden, 2nd edn, p. 211 (Edinburgh: Peter Davies). [50] N. A. John (Ed.) (n.d.) Holloway Jingles, Written in Holloway Prison during March and April, 1912 (published by the Glasgow Branch of the WSPU). [51] Unpublished letter dated 1 May 1912 from Mary C. Nesbitt to Miss Sinclair, Suffragette Fellowship Collection, Museum of London. [52] Vicinus, Independent Women, p. 260. [53] Elizabeth Robins (1913) Way Stations, p. 7 (London: Hodder & Stoughton). [54] Solomon, My Prison Experiences, p. 7. [55] Margaret E. Thompson & Mary D. Thompson (1957) They Couldnt Stop Us! Experiences of Two (usually law-abiding) women in the years 1909-1913, p. 46 (Ipswich: W. E. Harrison & Sons). [56] Ibid., p. 47. [57] Ibid., pp. 47, 49, 50. [58] Ibid., p. 50. [59] Ibid., p. 46.

Downloaded by [MPI Fuer Ethnologische Forsc] at 07:32 17 April 2013

129

JUNE PURVIS