Professional Documents

Culture Documents

BCAS v15n04

Uploaded by

Len Holloway0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

450 views78 pagesBulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars - Critical Asian Studies

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentBulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars - Critical Asian Studies

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

450 views78 pagesBCAS v15n04

Uploaded by

Len HollowayBulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars - Critical Asian Studies

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 78

Back issues of BCAS publications published on this site are

intended for non-commercial use only. Photographs and

other graphics that appear in articles are expressly not to be

reproduced other than for personal use. All rights reserved.

CONTENTS

Vol. 15, No. 4: OctoberDecember 1983

Daniel B. Ramsdell - Asia Askew: US Best-Sellers on Asia,

1931-1980

Jonathan Goldstein - Vietnam Research on Campus: The

Summit/Spicerack Controversy at the University of Pennsylvania,

1965-67

Zawawi Ibrahim - Malay Peasants and Proletarian Consciousness

Kevin J. Hewison - Political Conflict in Thailand: Reform,

Reaction, and Revolution by David Morell and Chai-anan

Samudavanija / A Review Essay

Robert Lawless - A Quasi History of the Central Vietnamese

Highlanders. Sons of the Mountains: Ethnohistory of the Vietnamese

Highlands to 1954 and Free in the Forest: Ethnohistory of the

Vietnamese Highlands, 19541976, by Huynh Kim Khanh / A

Review Essay

Cedric Sampson - The Origins of the Vietnamese Revolution:

Taking the Long View. Vietnamese Tradition on Trial 1920-1945 by

David G. Marr; Vietnamese Communism, 19251945 / A Review

Essay

Penelope B. Prime - Class Conflict in Chinese Socialism by Richard

C. Klaus / A Short Review

BCAS/Critical AsianStudies

www.bcasnet.org

CCAS Statement of Purpose

Critical Asian Studies continues to be inspired by the statement of purpose

formulated in 1969 by its parent organization, the Committee of Concerned

Asian Scholars (CCAS). CCAS ceased to exist as an organization in 1979,

but the BCAS board decided in 1993 that the CCAS Statement of Purpose

should be published in our journal at least once a year.

We first came together in opposition to the brutal aggression of

the United States in Vietnam and to the complicity or silence of

our profession with regard to that policy. Those in the field of

Asian studies bear responsibility for the consequences of their

research and the political posture of their profession. We are

concerned about the present unwillingness of specialists to speak

out against the implications of an Asian policy committed to en-

suring American domination of much of Asia. We reject the le-

gitimacy of this aim, and attempt to change this policy. We

recognize that the present structure of the profession has often

perverted scholarship and alienated many people in the field.

The Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars seeks to develop a

humane and knowledgeable understanding of Asian societies

and their efforts to maintain cultural integrity and to confront

such problems as poverty, oppression, and imperialism. We real-

ize that to be students of other peoples, we must first understand

our relations to them.

CCAS wishes to create alternatives to the prevailing trends in

scholarship on Asia, which too often spring from a parochial

cultural perspective and serve selfish interests and expansion-

ism. Our organization is designed to function as a catalyst, a

communications network for both Asian and Western scholars, a

provider of central resources for local chapters, and a commu-

nity for the development of anti-imperialist research.

Passed, 2830 March 1969

Boston, Massachusetts

Vol. 15, No. 4/0ct.-Dec., 1983

Contents

Daniel B. Ramsdell 2 Asia Askew: U.S. Best-Sellers on Asia, 1931-1980

Jonathan Goldstein 26 Vietnam Research on Campus: The Summitt

Spicerack Controversy at the University of

Pennsylvania, 1965-67

Zawawi Ibrahim 39 Malay Peasants and Proletarian Consciousness

KevinJ. Hewison 56 Political Conflict in Thailand: Reform, Reaction,

Revolution, by David Morell and Chai-anan

Samudavanija/reviewessay

Robert Lawless 60 A Quasi History of the Central Vietnamese

Highlanders; Sons ofthe Mountains: Ethnohistory of

the Vietnamese Highlands to 1954 and Free in the

Forest: Ethnohistory ofthe Vietnamese Central

Highlands, 1954-1976, by Gerald Cannon Hickey/

review essay

Cedric Sampson 63 The Origins of the Vietnamese Revolution: Taking

the Long View; Vietnamese Tradition on Trial, 1920

1945, by David G. Marr and Vietnamese Commu

nism, 1945-1945, by Huynh Kim Khanh/review essay

Penelope B. Prime 69 Class Conflict in Chinese Socialism, by Richard C.

Kraus/a short review

71 List of Books to Review and Correspondence

Index for 1983

Contributors

Jonathan Goldstein: Department of History, West Georgia

College, Carrollton, Georgia

Kevin J. Hewison: School ofHuman Communications, Mur

doch University, Murdoch, West Australia

Robert Lawless: Department of Anthropology, University

of Florida, Gainesville, Florida

Penelope B. Prime: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor,

Michigan

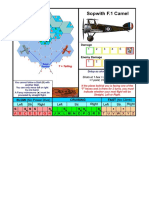

Front cover graphics courtesy ofDaniel B. Ramsdell

Daniel B. Ramsdell: Department of History, Central Wash

ington University, Ellensburg, Washington

Cedric Sampson: Department of History, Los Angeles

Mission College, San Fernando, California

Zawawi Ibrahim: Development Studies, School of Social

Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, West Malaysia

The fine drawings ofIndonesia appearing in this issue are by Hans Borunt .

Leiden. The Netherlands.

Asia Askew: U.S. Best-Sellers on Asia, 1931-1980

by Daniel B. RamsdeU

American Images of Asia

The idea for this project emerged from twenty years of

teaching American college students, including beginning

and advanced undergraduates, about Asia and some of its

parts. For years my assumption and that of many col

leagues, administrators and curriculum specialists was that

college students would not enroll in courses in non

Western areas unless they were interested in advance and

therefore receptive to the information provided. Thus,

American institutions of higher learning have only rarely

required the study of Asia or other segments of the non

Western world. Teachers of such subjects, moreover, have

often been smug in the conviction that at least their

students were not captives, but vitally interested in the

subject. My own experience suggests that juniors and

seniors signed up for courses on Asian History are indeed

willing and receptive, frequently superior students major

ing in History. Their receptiveness, however, does not

necessarily mean that they are well informed in advance.

Instead, I have come to the conclusion that the information

many American college students have about Asia is actu

ally "misinformation" presumably derived impressionisti

cally from a variety of uncatalogued sources.

In teaching World Civilization mostly to freshmen

general education students (some of them "captive") I

discovered that, for many, the acceptance of my informa

tion on Asia (and other less familiar parts of the world) was

determined mainly by the degree to which my statements

conformed to their existing notions and beliefs. This

seemed to confirm the suspicion that facile generalizations

about Asia and Africa, for example, were more common

than for territories whose peoples and cultures were better

known because knowledge of them was part of the common

lore of the land and had been presented more frequently at

earlier educational levels. Both phenomena-impression

istic misinformation and facile generalizations about

Asia - have remained surprisingly stable over the past two

decades. Reflecting upon this stability I ultimately decided

to seek the sources ofthe generalizations from which misin

formation has come and also the reasons for their

durability.

2

Undoubtedly the most common sweeping generaliza

tion I have heard over the years about Asia is that the

people of Asia regard human life cheaply. This is a view

often expressed by both the "interested" and the "general"

student, as well as many non-students. The perpetrators of

this cliche usually make no distinction between various

parts of Asia. The other very common generalization is

closely related to the concept inherent in the first: the

notion that the world is somehow divided into East and

West and that they are irrevocably different and distinct

from each other. Associated with this idea is the belief, in

America at least, that the West means Europe and its

cultural offshoots (especially North America) and the East

embraces everything else, presumably beginning with

Turkey and the "Near East." It is evident that this view still

prevails in the United States where politicians talk about

preserving Western civilization and in the popular press

where the East-West struggle is perpetually discussed.!

Despite the two-day Cancun Conference in October 1981

there is virtually no recognition in the American media of a

North-South or rich-poor dichotomy in world affairs. We

have been conditioned to think that the world is divided

into East and West. The myth of East-West world division

has been studied in a fascinating but little recognized book

by John M. Steadman, The Myth ofAsia (Simon and Schus

ter, 1969). Steadman and others

2

have assailed the cliches

derived from these generalizations, but they have persisted

nevertheless.

In recent years there have begun to appear serious

studies of image formation, including some excellent ones

on American images of Asia. The pioneer work was Harold

Isaacs' highly acclaimed Scratches on Our Minds: American

Views ofChina and India. This lengthy book first appeared in

1958 and has been reprinted and revised frequently there

1. In this struggle, however, at present the "evil" East is strangely led by

the U.S.S.R., a European nation and the East-West struggle has thus

become a contest between the "Free World" and Communism.

2. For example, Edward Said, Orientalism (New York, 1978).

after. Among other things, Isaacs ponders the sources of

popular images of China and India and includes commen

tary on motion pictures, best-selling books, and other ex

pressions of popular culture. The heart of the study, how

ever, was based upon interviews with 181 persons whom

Isaacs regarded as leaders in American life at the time the

study was undertaken. A book of essays, edited by Akira

Iriye and published in 1975 under the title of Mutual Images:

Essays in American-Japanese Relations, contains several il

luminating expositions. The two best essays are Nathan

SBBgB IiIr lonl5

uni&l fBnilfic5

Glazer's "From Ruth Benedict to Herman Kahn: The Post

war Japanese Image in the American Mind" and "U.S.

Elite Images of Japan: The Postwar Period" by Priscilla

Clapp and Morton Halperin. Like Isaacs' study, both of

these are primarily concerned with elites and their percep

tions. Also noteworthy is Sheila Johnson's 1975 book

American Anitudes Toward Japan, 1941-1975 which ex

ConcubinB5, gBi5hBI

onBI bBndH5,

PUB5I5, IriIdBtl, Bnd IIBR5

all play their parts in the drama of-

Steghen ChaSe - the rugged, brilliant, young

American businessman whose driving ambition brings

him to the brink of disaster

Hester- his exotically beautiful, strangely tormented,

young wife

HO - the powerful Chinese merchant prince, wise and

wily, who eventually becomes Stephen's friend

Kendall - smooth and ruthless, Stephen's associate

in the company, who eventually becomes his most dan

gerous enemy

An unforgettable story of bold Americans in China on the eve

of the revolution, trying to cope with an alien civilization that

is itself in turmoil.

"An utterly fascinating tale" -BOSTON TRANSCRIPT

A PYRAMID BOOK 600 Cover painting by Bob Abbett Printed In U.S.A.

Graphics courtesy ofDaniel B. Ramsdell

amines popular attitudes and emphasizes the use of best

sellers, but Johnson draws no conclusions of significance

and confines herself to a single nation.

There are other generalized treatments of certain as

pects of the image of Asia in the United States or the

Western World. Raymond Dawson's The Chinese

Chameleon: An Analysis 0/ European Conceptions o/Chinese

Civilization (London, 1967) is a broad historical examina

tion of European views of China, based mainly on litera

ture and art. Robert McClellan, The Heathen Chinee: A

Study 0/ American Anitudes Toward China, 1890-1905 (Col

umbus, OH, 1970) is a scholarly monograph based on

literary, magazine and congressional sources for the period

in question. Also scholarly but more analytical is The Un

welcome Immigrant: The American Image o/the Chinese, 1785

1882 (Berkeley, 1969) by Stuart Creighton Miller. A more

3

recent book by the well known historian of modem China,

Jerome Ch'en, China and the West: Society and Culture 1815

1937, contains a chapter on mutual images, again derived

mostly from literature and the press. In 1937 Eleanor Tup

per and George E. McReynolds published a surprisingly

good book, Japan in American Public Opinion, but the public

opinion studied by the authors was limited to newspapers.

More recently Jean-Pierre Lehmann studied mostly Eng

lish and French literary material to produce The Image of

Japan: From Feudal Isolation to World Power (London,

1978). All of the above concentrated upon a single country

in East Asia. The studies of Steadman and of Edward Said

(see below) are wider in scope, but are also based heavily

on literary, artistic and philosophical sources of Western

literature and "high culture."

Although the studies noted here represent a good start

toward the definition of American images of Asia, they

neglect certain areas altogether and leave unanswered

questions about the sources of popular attitudes. In this

study I intend to examine a single source of such attitudes

about Asia: best-selling books in the United States.

3

The Pattern of Dest-Sellers on Asia

There is a substantial literature about best-sellers in

this country, although most of it is out-of-date and none at

all is specific in treatment of non-Western peoples or na

tions. The major studies of best-sellers are Frank L. Mott's

Golden Multitudes (New York, 1947) which traces Ameri

can best-sellers from colonial times until the date of publi

cation, and James D. Hart, The Popular Book: A History of

America's Literary Taste (New York, 1950) which is a some

what more critical study. Mass Culture: The Popular Arts in

America (Glencoe, Ill., 1957), edited by Bernard

Rosenberg and David White, consists of articles on various

features of popular culture, including books. Lists of best

sellers with comment is provided in Alice Hackett's Eighty

Years of Best Sellers (New York, 1977), previously pub

lished as Sixty Years of Best Sellers. By far the best critical

study of American best-sellers in general is Suzanne Ellery

Greene's Books for Pleasure: Popular Fiction 1914-1945

(Bowling Green, OH, 1974). There are also many articles

on the subject, few of them of a serious nature. Most of

those who write about best-sellers are deprecatory of their

subject, but seem to think that such popular books reflect

middle-class thinking and values in American society.

From the inception of best-seller lists there has been dis

agreement over their validity and the manner of their prep

aration. Also controversial has been the subject of the

ingredients necessary for best-seller success. Much has

been written about this, especially in high-brow magazines

like The Saturday Review in the 1940s and 1950s. Interest in

this subject has waned in recent years and, fallible as the

lists may be, this study will not take up the question of their

validity or the related issue of how they are created.

In determining the geographical scope of "Asia" for

this study, I have included South and East Asia, but not the

so-called "Near East." This latter area, traditionally seen

3. There are obviously other important sources of images of Asia. In the

future I also intend to examine motion pictures, textbooks, magazines and

newspapers.

by Europeans and Americans as that of Islamic culture and

civilization, is the subject of immense quantities of print in

the United States, but very few best-selling books. The

general Western misunderstanding of this part of the world

is treated in fascinating fashion in a recent book by Edward

Said,Orientalism.

In assessing American best-sellers about Asia and

Asians in the following pages, I started by preparing a

year-by-year list of books (Appendix B) which are also

categorized according to their major characteristics. Here I

have registered all books appearing on the weekly best

seller lists of The New York Times Book Review and Pub

lisher's Weekly between 1931 and 1980. I selected 1931 as an

innaugural date largely because definitive lists are not av

ailable earlier and because there are few books about Asia

before 1931 in the more general compilations of best

sellers.

4

In order to understand the accompanying graphs il

lustrating the fortunes of best-sellers on Asia it is necessary

to refer to Appendix A which explains the point system

used. A quick glance at the graphs yields some rather

obvious conclusions. Interest in books about Asia

remained low throughout the 1930s with no more than two

books a year through 1941. The years ofthe Second World

War brought about a quantum leap in best-sellers on Asia,

many of them non-fiction dealing with aspects of the war

itself. In 1942 there were ten books and in 1943 twenty,

twice the number in one year than had made the list for the

whole previous decade. The all-time zenith in American

publishing for best-selling books about Asia was 1943, both

in number of titles and in the accumulation of points ac

cording to the system in use in this study. The remaining

war years also saw high figures which began to decline with

the termination of hostilities. The late 1940s and 50s also

produced several reminiscences of wartime. A moderately

high level was maintained in this period, although the

year-by-year pattern was uneven. The average number of

best-seller titles on Asia from 1947 to 1960 was 7.7.

Beginning with the early 1960s interest in Asia as

manifested in best-selling books began to diminish'. The

decline can be accounted for in part by the general dis

interest of Americans in the outside world, a tendency

which grew stronger, ironically and devastatingly, with the

4. Popular impressions in writing were, of course, present before 1931

Certain kinds of books which were later made into movies and contributed

significantly to American images of China included the Fu Manchu books

by Sax Rohmer (published between 1913 and 1957) and the Charlie Chan

books by Earl Derr Biggers which appeared serialized in the Saturday

Evening Post from 1925 to 1932. These books did not make best-seller lists,

although portions were undoubtedly read by i 1 1 i ~ n s . Others in a similar

vein include a series ofMr. Moto books by John P. Marquand from 1935 to

1942. Moto and Chan were Japanese and Chinese detectives who were

suitably obsequious to the Westerners among whom they dwelt. Fu

Manchu was the archtypical sinister villain, the popular embodiment of

the Yellow Peril. Another series featuring a Chinese detective was the

Judge Dee series by Robert van Gulick, first appearing in the U.S. in 1958

and lasting until the author's death in 1967. Authors who influenced

scholars and specialists and hence had an important indirect cumulative

impact include such persons as Edgar Snow, Nym Wales, Agnes Smedley,

and Anna Louise Strong, all of whom wrote on China, mostly in the 1930s

and 1940s. Except for Snow's wartime People on Our Side, none of their

works made best-seller lists, It is fair to conclude, therefore, that they had

relatively scant direct influence on popular images of Asia.

4

VI

21l

til

16

t4

12

10

8

6

4

2

1200

1100

1000

900

800

700

600

500

400

300

20.0

100

Total

number of

best

sellers

Points

Non-Fiction Fiction

'-.----- ~ -

o "'"VI4' a v/'4<,-' 1' , VA--J

Jl 12 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 4344 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 5859 60 61 62 6364 65 6667 6869 70 11 72 73 74 75 76 17 7b 79 bO

Year

intensification of the Vietnam war. That war, moreover

unlike earlier encounters, did not provide publishers with

the opportunity to glorify the deeds of heroic military men

in best-selling books.

Undoubtedly the most common sweeping generaliza

tion I have heard over the years about Asia is that the

people of Asia regard human life cheaply.

Aside from war, American popular interest in Asia

has been slim. The blockbusting best-sellers on Asia in

recent years (such as ShOgun, Dynasty and The Far Pavilions,

set respectively in Japan, China and India) all featured

heavy doses of warfare and other violence. To be sure, this

may also be said of many other best-sellers, particularly

lately. The other noticeable trend of the last twenty years

has been the appearance of several major best-sellers with

essentially Asian locales or themes. Of the overall total of

fifty best-sellers frbm 1961 to 1980, eleven ranked in the

"A" popularity grade. In contrast, between 1946 and 1960

only three books out of 121 achieved "A" ranking. There

were four books in this category before 1946.

In his famous study, Scratches on Our Minds, Harold

Isaacs contended

5

that American interest in China was

much greater and more intense than interest in India the

other large and ancient civilization in Asia. Isaacs'

aPI?ears to be confinned by best-sellers lists, although

Chma leads all other countries by a margin narrower than

might be expected. In the fifty year period covered by this

study there were fifty-six books entirely or partially about

China. This number was split almost evenly between

twenty-nine fiction and twenty-seven non-fiction titles.

Japan ranked second with fifty-five (only thirteen fiction,

but forty-two non-fiction) while India was third with forty

three (twenty-five fiction and eighteen non-fiction). No

other individual nation accounted for more than eleven

(Bunna), but there were thirty books, mostly non-fiction

travel or memoirs, that were too generalized in content to

break down by country. According to the point system

Ch.ina outdistanced the others by a wider margin with 5,600

po1Ots (3,770 fiction, 1,830 non-fiction). Japan's point total

was 3,334 (1,483 fiction, 1,851 non-fiction) and India's

3,267 (2,284 fiction, 983 non-fiction). The next highest

accumulation of points was 983 for Vietnam.

The fiction books on China fall mainly into the two

categories of H (Americans or Europeans in Asia) and J

(Asians in an Asian setting). Of the twelve books in the

latter grouping eight were by Pearl Buck whose overall

influence and career will be discussed later. There were

fifteen fiction titles set in China in which the main

characters were Westerners through whose eyes the picture

of China and her people was presented. These books began

5. On page 239, for example. Harold Isaacs, Scratches on Our Minds.

American Views o/Chino andlnd;a (White Plains, N. Y., M. E. Sharpe, 1980

ed.).

6

with Alice Tisdale Hobart's Oil for the Lamps of China in

1933 and continued until the present, the most recent ex

ample included here being Manchu, by Robert Elegant, in

1980. of the H category books featured foreigners

who are mIlItary men or soldiers of fortune, but the trend is

not overwhelming. Oil for the Lamps of China has as its

protagonist a businessman, The Keys ofthe Kingdom a priest,

and The Black Rose, a historical novel, an English

The vision of China and the Chinese people

Imparted through the words and thoughts of the Western

heroes of these novels is a consistent one which will be

taken up in greater detail later.

. surprise at finding Japan with fifty-five best-selling

tItles, Just one less than China, is mitigated by the realiza

tion fourteen of them, or twenty-five percent, were

non-fictIon works published during the war years. Before

War II there was only one book with Japan as its

subject to make U.S. best-seller lists. This was North to the

Orient, by Anne Morrow Lindbergh in 1935. About twenty

percent of it concerned Japan. One may conclude, there

fore, that popular interest in Japan, as reflected in best

selling books, only began with the war.

. . The trend for non-fiction war books to dominate pub

hsh10g on Japan continued through the late 1940s and the

entire decade of the fifties, though not with such great

intensity after 1945. Of the twenty-seven best-sellers on

Japan from 1946 to 1959, twenty were directly related to

the Second World War in the fonn of memoirs, histories,

and personal reminiscences. Indeed, of the fifty-five titles

altogether on Japan, thirty-five, or sixty-four percent, were

The most common types were wartime jour

nalIstIc accounts and biographies or memoirs of U.S. mili

tary figures. There is little doubt that the major American

popular image of Japan is in connection with war. 6

ranked a close third among countries of Asia,

both 10 number of books and in points.

7

Fiction titles on

India were particularly common with twenty-five, almost

double the number on Japan. The fiction works on India

began with Louis Bromfield's two major best-sellers about

Americans and Europeans in India, The Rains Came (1937)

and Night in Bombay (1940). Overall best-seller interest in

India was highest during and shortly after World War II.

From 1946 to 1960 there were seventeen fiction titles on

India, seven by John Masters whose specific contributions

will be taken up later. After 1960, interest of any sort in

India virtually disappeared. From 1961 through 1980 there

were but six best-sellers on India, two of them fiction works

of recent vintage by M. M. Kaye.

The majority of fiction books about India fall into the

H category: Americans or Europeans in Asia. Most of the

seventeen titles so classified were historical and reflected

the heritage of British imperialism in the sub-continent.

6. My impression is that Japan still conjures up Pearl

Harbor In the minds of a great many Americans. From my teaching,

moreover, I have concluded that December 7, 1941, is the best known

single date in American history.

7. The locale of some of the books included under India is in what is now

Pakistan: Most of are fictional titles with historical settings where the

IS always deSIgnated as India. It is, therefore, appropriate to

Include o.nly one national category, namely India, for that portion of

South ASIa presently composed of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.

There was only one India book with an East-West love

theme as the major component. The romance in this case

(Elephant Hill. by Robin White, 1959) featured an Indian

man and an American woman. Many of the books on

China, Japan, and India contained sub-themes of East

West romance, but it was not often the major subject.s

Ordinarily, moreover, the man has been Western and the

woman Asian.

The relative shortage of non-fiction best-sellers about

India may be explained by the absence of warfare there in

which Americans participated. Elsewhere in Asia, where

Americans have fought, books with war themes have been

prominent in the non-fiction realm. In the late 1940s and

early 1950s there were several journalistic accounts, usu

ally covering much of Asia, in which India was included.

Since Indian independence in 1947 there have been only a

sporadic few non-fiction best-sellers focusing on the sub

continent, mainly travel accounts and ambassadorial recol

lections. I am tempted to conclude that Americans lost

what little interest they had in India after the British de

parted. In any event, it is doubtful if Americans have

formed strong impressions of India from best-selling books

in the past fifty years.

After China, Japan, and India no single nation in

South or East Asia has attracted much interest in American

publishing. Taken as a whole, and including general books,

the list on Southeast Asia runs to forty-five books (twenty

four fiction and twenty-one non-fiction). The biggest fic

tional best-seller about Southeast Asia was The Ugly Ameri

can (1958) which was set in several fictional countries.

There have been ten best-sellers on Indonesia, nine of

them fiction, mostly in the H category and all published

before 1962. They generally concern the colonial experi

ence and fail to depict Indonesians in a meaningful way.

Burma has been the subject of eleven titles. The six non

fiction books on Burma were by Americans or Britons

relating their personal experiences during the Second

World War. The five fiction works include two with a

Western male-Burmese female love story, while the

other three are wartime novels. (The love stories were also

set in wartime.) Of the seven best-sellers on Vietnam all

were in some way related to the American presence there

and to warfare as well. Graham Greene's The Quiet Ameri

can (1956) long preceded direct U.S. involvement in the

Vietnam war, but centered its attention upon clandestine

American activity in the former French colony. Surpris

ingly, in view of the fifty years when it was an American

possession, not much interest in the Philippines is evident

in best-seller lists. Only five books on the Philippines are

included. They all appeared between 1943 and 1946 and

were all, needless to say, war related.

There were also three best-sellers on Malaysia, none

of them noteworthy, and one each on Thailand, Laos and

Kampuchea. The only popular book about Thailand ever

published in the United States was Margaret Landon's

Anna and the King of Siam (1944). This is the book from

8. Three times for Japan: The Hidden Flower. by Pearl Buck (1952),

which came the immensely popular stage and screen musi

cal The King and I which has been viewed in one form or

another by many millions of Americans.

9

Although the

book itself did not have such great impact, the result of this

single work has been to perpetuate one of the most monu

mental insults of modem times upon the people of Thai

land and their king. A recent article by William Warren has

exposed the credentials of Anna Leonowens whose two

nineteenth century books served as the basis for Landon's

best-seller,lo but the damage has already been done. It is

unlikely that the American image of Thailand will be re

paired in the near future.

Aside from war, American popular interest in

Asia has been slim. The blockbusting best-sellers

on Asia in recent years (such as ShOgun, Dynasty.

and The Far Pavilions, set respectively in Japan,

China, and India) all featured heavy doses of

warfare and other violence.

The one book on Laos was Thomas Dooley's account

of his own medical work there in the 1950s. It was patroniz

ing to the Laotians. The only study featuring Kampuchea

was the book by the British journalist William Shawcross,

Sideshow (1978). This is one of the few intelligent studies of

any aspect of Southeast Asian politics to make U.S. best

seller charts. There is little doubt that its climb was due to

the subtitle: Kissinger. Nixon, and the Destruction of

Cambodia and the criticism of American foreign policy

implied therein. Overall, works on Southeast Asia, gener

ally and particularly, have not conveyed favorable impres

sions to Americans of the inhabitants of this part of the

world. The individuals portrayed, especially in fiction, are

invariably depicted in a negative manner.

There were ten U.S. best-sellers on Korea, nine of

which, including two in fiction, concerned the Korean War

and American participation in it. This total includes three

specific studies of General Douglas MacArthur. The rem

iniscences of MacArthur (1964) and the recent full length

biography by William Manchester (American Caesar. 1978)

also contain material on Korea, but have been classified

under East Asia because of their broad scope. The only

book about Korea not specifically related to war was Pearl

Buck's 1963 novel, The Living Reed which carried a fictional

Korean family through several generations including war in

the 1950s.

9. The first film version appeared in 1946 under the same title as the book.

Rex Harrison starred as King Monkut. The Rodgers and Harnmerstein

musical version appeared on Broadway in 1951 and on film in 1956

starring Yul Brynner. Both were acclaimed critically and did well at

box The musical production has been frequently revived in touring

compames and there was even an unsuccessful attempt at a television

series in 1972.

Sayonara. by James Michener (1954), You Only Live Twice. by Ian Fleming

10. William Warren, "Anna and the King: A Case of Libel," Asia, 2:6

(1964), and once for China: The World ofSuzie Wong. by Richard Mason

(MarchI April 1980), pp. 42-45.

(1957). 7

"The Big Five"

Of the 178 authors listed in Appendix C, very few have

had great cumulative impact over the years. The names of

five stand out above all the others. They are Pearl Buck,

Lin Yutang, John Masters, James Michener, and James

Clavell. The first two of these were regarded by their con

temporaries as "friends" of Asia, and the latter three are

primarily adventure writers of recent years. Collectively

they may be considered "The Big Five" of U.S. best-selling

authors on Asia.

Pearl Buck

Pearl Buck was the first in point of time and also

impact. She was easily the most influential writer of popu

lar novels about Asia to publish in the United States. She

was an active author and speaker for over forty years and is

still one of the best known American names associated with

China and things Chinese. 11

Buck was of missionary background which is fitting

since missionaries provided the most important general

source of person-to-person contacts with Chinese prior to

World War II. Although she was born in the United States

in 1892, Buck was taken to China by her parents while an

infant and she remained there for most of the next forty

years. She could read, speak and write Chinese. Until fame

found her in middle age her sojourns in the U.S. were

relatively brief. She attended Randolph-Macon Women's

College from which she graduated in 1914, then returned to

China where she married John Lossing Buck, an agri

cultural specialist, in 1917. She returned to the U.S. with

her husband and received an M.A. in English from Cornell

University in 1926. By this time she had begun to publish

articles on China in magazines like Atlantic Monthly , Forum,

and Asia. Pearl Buck was an outstanding example of the

middle class American who, though not born to wealth,

was well educated and had respected family status. She also

grew up in privileged circumstances by virtue of her alien

status in China.

During the period covered by this study Buck had

twice as many books on U.S. best-seller charts as the next

author-John Masters. Her sixteen books amassed a total

of 1,818 points which is almost double the total of James

Michener in second place. Buck had eleven fiction titles on

China, plus one each on India, Japan and Korea and

another that related to both China and Burma. She had two

non-fiction best-sellers, one mainly about Japan and the

other largely autobiographical about growing up in China.

She also wrote many other books which did not make the

best-seller lists and countless articles, many in popular

magazines such as Good Housekeeping. Her works, more

over, spanned a longer period of time than any other au

thor on the list: thirty-eight years from The Good Earth in

1931 to Three Daughters of Madame Liang in 1969. The

cumulative influence of these books was very great, but

Pearl Buck kept herself in the public eye in other ways as

well.

11. Many of the prominent Americans interviewed by Harold Isaacs cited

Pearl Buck and her books as the source of their original exposure to

China. See Isaacs, pp. 155-158.

Of "The Big Five" Buck was the only author who

produced fiction that primarily concerned Asians in Asia.

Her first such effort, The Good Earth, catapulted Pearl Buck

to fame in the United States and much of the rest of the

world. Despite some rather petty criticism, she was

awarded the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1931.

12

The Good

Earth was a simple, sentimental tale of a hardworking

Chinese man, his good and bad times, and the tribulations

encountered by himself, his unlettered wife, and his family.

The book was presumed to uphold the simple dignity of the

earth-bound Chinese peasant and evoke sympathy for him

in affluent American readers. It was, in any event, an

instant hit and Pearl Buck became America's number one

expert on China, a role which she apparently relished over

much of the next four decades.

Once established as a China expert, Pearl Buck's

name began to pop up in the American press almost any

time something pertaining to China did. This included

controversy. In 1933 the Presbyterian Board of Foreign

Missions threatened to expel Buck from their membership

following an article in Harper's which criticized the arro

gance of some foreign missionaries in China and also

questioned aspects of Christian theology. She implied, for

example, that the doctrine that one is eternally damned

unless saved by Christ was a superstition that should not be

inflicted upon the Chinese. 13 After fundamentalists and the

press picked up the issue, Buck resigned from the mission

board later in that year. Thereafter, in her lectures and

writings she seemed to drift away from the traditional

missionary position with respect to China.

There was a certain amount of criticism of Buck's

works in the United States in the 1930s. For example, in

1935, a Kansas City mother attacked The Good Earth as

"filthy" and sought to have it banned from public schools.

No nationwide movement of this sort materialized and

most criticism of Buck in this period came from Chinese.

Elitist Chinese scholars took her to task for concentrating

on what they regarded as the lowliest member of society.

One scholar, Kiang Kang-hu, in a long article in The New

York Times Book Review in 1933, attacked the accuracy of

Buck's portrayal of Chinese customs and declared that she

caricatured Chinese by emphasizing "a few special points

and [she] makes things appear queer and unnatural to both

Western and Chinese eyes."14 Buck answered this and

other criticism so vigorously that she, not the Chinese

scholars, was accepted in the U.S. as the real expert on

China. It is clear, however, that she helped promote the

cliche that Chinese (and hence "Orientals" of all descrip

tions) valued life cheaply. She said as much in an article in

Asia in October 1937 while commenting on the inhumanity

of the war then in progress between China and Japan. 15

12. Some criticized the selection on the grounds that the Pulitzer was

supposed to go to a distinctively American work by an American author.

Many thought Pearl Buck and The Good Eanh did not meet these criteria.

13. Pearl Buck, "Is There a Case for Foreign Missions?," Harper's Maga

zine, 166:2 (Jan. 1933), pp. 143-155.

14. The New York Times Book Review, Jan. 15, 1933. The article by Kiang is

on pages 2 and 6, while Buck's reply appears on pags 2 and 17.

15. "What we now see in China, therefore, is the combination of parts of

two civilizations, without the restraint of the balancing parts; that is, a war

carried on with modem weapons, the product of the West, and with a

8

Indeed, throughout the Sino-Japanese conflict Pearl

was busy in the U.S. in support of the Chinese cause in

particular and in calling attention to troubles in East Asia in

general. It is apparent that she was awarded the Nobel

Prize for Literature in 1938 mainly out of sympathy for

China in her hour of peril. Nearly everyone in the United

States (and many in Europe as well) who commented on

the Nobel selection indicated that she was not a literary

giant, but many claimed that she deserved it nevertheless.

Actually, I think that the Nobel committee as well as many

Americans who read her writings on China, felt that the

downtrodden people of China (like the hero and his wife in

The Good Earth) were the ones who deserved the recogni

tion. Granting the Nobel Prize to Pearl Buck was as close as

they could get to meeting this recognition.

Retaining her reputation as a China expert after Pearl

Harbor, Buck began to take up the question of race pre

judice in her lectures and other public appearances. She

was unmistakably a "liberal" on this issue and it is likely

that she contributed more than she has been credited for to

the liberal movement against racism in America because

she was taken seriously as one who "really understood

Orientals." In the war years she frequently attacked

American racism and smugness, contending in a February

1942 speech that "the peoples of Asia want most of all in

this war their freedom" [from white Western oppression].

She called on the U.S. to practice the democracy it pro

fessed, implying thereby that this had not been the case in

the past. In addition, she claimed that to many Asians the

United States and Britain appeared to be fighting more to

save imperialism than for the freedom of all people. She

predicted by implication the postwar feelings of nation

alism and anti-colonialism that stunned the world. She was,

of course, criticized in the American press for the expres

sion of these unpopular views, but she was also recognized

as a member of the "establishment" whose views could not

be sloughed off with contempt.

After the Second World War Buck remained active in

a variety of causes as well as continuing to produce books in

rapid order. She published five novels in the late 1940s

under a pseudonym, though none concerned China or

other parts ofAsia and none was a best-seller. In 1948 Buck

testified before a Congressional committee against univer

sal military training which she called a "breeder of war. " In

the same year she spoke out against censorship in the U.S.

which she apparently thought was a serious danger. In the

early 1950s, like almost every prominent American with

experience in China, she was attacked by McCarthyites. She

was not a major target, but non-approval from HUAC

(House Un-American Affairs Committee) caused cancela

tion of a high school commencement speech in Washing

ton, D.C. in 1951. Despite her reputation and continued

commentary on Chinese affairs, Pearl Buck rarely returned

to China after she became famous. In any case, she was not

really welcome there. Even in her later years, after the

thaw had begun in American-Chinese relations, she was

refused a visa by the People's Republic.

In the last two decades of her life Buck devoted much

of her time to seeking care for neglected children of Ameri

can fathers and Asian mothers. She set up a foundation for

this purpose while she and her second husband, publisher

Richard J. Walsh, adopted eight children of various back

grounds. Through these means she managed to remain in

the public eye in the U.S. as such activities were ideal for

reportage in women's magazines. It is probably fair to say,

however, that the heyday of her influence was in the late

1930s and the wartime years. Her postwar influence was

largely residual, based on the mark she had made earlier.

At the time of their publication most of Pearl Buck's

books were reviewed favorably by critics. She was seen as

one who "understood" China and the Chinese in a nation

which did not. Those who sang her praises often did so for

her perceived contributions to bridging the East-West gap.

That such a gap existed was taken for granted by all Ameri

cans who ever said anything about it and apparently is still

accepted as a kind of immutable principle. The influence of

the likes of Aristotle and Rudyard Kipling is very hard to

overcome. In Buck's later novels, like The Hidden Flower,

the main theme was East meeting West. Prominent figures

praised her for this. In reviewing her autobiography Edgar

Snow lauded her for contributions to the understanding of

China. 16 Harold Isaacs also praised Buck for her positive

contributions to the American image of China and the

Chinese.

Despite the favorable reviews, by the time of her death

in 1973 Pearl Buck had gone out of fashion as a China

expert. Her works could then be attacked as "puerile. "17

Even in the days of her greatest popularity, the praise had

been mixed with negative comments. For example, critics

often referred to her style as "biblical," meaning that it was

ponderous and moralistic. It was also noted that she dealt

mainly in types and that her characters lacked psychologi

cal insight. She was often described as a "woman's

novelist." Apparently, this meant that she was sentimental

to a fault. Christian critics, Catholic and Protestant, were

also sometimes harsh. A Jesuit journal called her

dogmatic, 18 while the obituary in Christianity Today pointed

out that many evangelicals considered her hostile to them

and their sense of mission. 19

While Buck sought to banish the stereotype of the

yellow-menacing Chinese and to portray them as individu

als with common human attributes, it is also true that the

characters in her books often emphasized rather than min

imized the differences between "East" and "West." A

perceptive comment on Buck and her popUlarity was that

she "makes her followers feel they are getting a learned

insight into ways and things Chinese. "20 Actually, stories

like The Good Earth had plots that were essentially Ameri

can: poor boy makes good by dint of hard work and self

16. See Edgar Snow, "Pearl Buck's Worlds," a review of My Several

Worlds, by Pearl S. Buck, in Nation, 179:20 (Nov. 13, 1954), p. 426.

17. So described by Helen F. Snow (Edgar Snow's ex-wife) in The New

Republic, Mar. 24, 1973, p. 28.

18. Dorothy G. Wayman in a review of My Several Worlds in America, 92:6

(Nov. 6, 1954), p. 160.

spirit of utter disregard for individual human life, which is the result of life

19. Christianity Today, Mar. 30, 1973, p. 29.

in the Orient." Asia. 37:10 (Oct. 1937), p. 672. "Western Weapons in the

Hands of the Reckless East," by Pearl Buck. The title of this piece is also

20. Louise Lux. review of Kinfolk in New York Times Book Review, Apr. 24.

revealing.

9 1949, p. 30.

sacrifice. Other assessments of Buck as a literary figure

described her respectively as a fatalist regarding women, 21

a naturalist possibly influenced in college by Zola,22 and as

a novelist of the depression.

23

Her preeminence as a pur

veyor of popular impressions of China to the American

public was and remains, however, unchallenged.

Before taking up the careers of the other super best

sellers, it seems appropriate here to include a brief sum

mary of Buck's best-sellers in the order of their appear

ance. The Good Earth, her first best-selling novel, was the

most widely acclaimed of her many works. It was the story

of a Chinese peasant, Wang Lung, and his wife and their

rise to prosperity through. perseverance, hard work and

many vicissitudes. Original reviews of The Good Earth were

almost all favorable. This work was followed in 1932 by

Sons, a sequel which concentrated attention mainly on one

of Wang Lung's sons who became a warlord. Sons was

received less positively than The Good Earth. The third

book in the House ofEarth trilogy, A House Divided, which

appeared early in 1935, did not make U.S. best-seller lists.

It focused on the third generation of the Wang family and

was set in the period ofthe revolution. Reviews of this book

were mostly negative with one American critic describing it

as "the worst novel ever written by a competent novel

ist. "24

Buck's next best-seller was Dragon Seed in 1942. It was

largely a story of resistance and collaboration in the war

with Japan. One "good" Chinese family contended against

a "bad" one. The Chinese in it remained peasants and

were, as before, presented as both simple and simple

minded. It received mixed reviews. The Promise in 1943 was

a sequel to Dragon Seed and also set in Burma during the

unsuccessful campaign against Japan. In this novel Buck

stressed white racism against Chinese who were again de

picted as simple, naive, and hard working. Most American

reviewers of The Promise were positive, but some

questioned her harping upon the faults of the U.S. and

Britain in the Burma campaign.

Pavillion of Women in 1946 concerned a Chinese

matron in a wealthy family who brings in concubines to

please her husband and seeks personal happiness for her

self. There was a missionary of no particular sect in this

novel and also a spiritual message. The heroine in her later

life becomes a compassionate "do-gooder." Reviews were

mixed. Peony in 1948 was focused on Jews in China with a

story about a bondmaid who falls in love with a Jewish boy.

The love is unrequited and Peony ends up in a convent. The

reviews were largely negative.

Kinfolk, the following year (1949) was soap opera. A

Chinese scholar living in New York finds that two of his

children are drawn back to China by their own inclinations

and the other two are shanghaied back. As a result all kinds

of complications arise, pitting members of the family

against each other. In this novel is seen another favorite

21. Margaret Lawrence. The School of Femininity (Port Washington.

N.Y., 1936), pp. 318-323.

22. Oscar Cargill, Intellectual America (New York, 1941). pp. 146-148.

23. Carl Van Doren, The American Novel, /789-/939 (New York, 1940), p.

353.

24. Malcolm Crowley, "Wang Lung's Children," New Republic, May 10,

1939, p. 24.

theme of treatises on China-the conflict of generations

and of tradition versus progress. In 1951 God's Men con

cerned two American men, both sons of missionaries born

in China. They go different ways, one to become "good,"

the other "bad." It was a sentimental story that was both

praised and attacked by contemporary reviewers.

Appearing two years before Michener's Sayonara,

Buck's next best-seller, The Hidden Flower (1952) was prin

cipally a love story with an "unhappy" ending between an

American military man and a Japanese woman. The re

views were widely mixed with some lambasting it and

others singing its praises. Buck strayed from China again in

1953 with Come My Beloved which was set in India and

focused on altruistic American missionaries who, over sev

eral generations, get progressively closer to the people.

One reviewer described the theme of this novel as "man

kind is all one family."2s In 1956 Imperial Woman was a

fictionalized biography of the Empress Dowager Ci Xi

(Tz'u Hsi) who was portrayed in a flattering manner. Most

of the reviews of Imperial Woman were mildly positive.

Buck usually sought topicality. Letters from Peking in

1957 features a part-Chinese man who remains in China

when the Communists gained control. He writes a final

letter to his American wife in Vermont, whereupon the

wife recalls with sentiment the things from their past. This

novel was praised as a novel of "understanding," apparently

of East and West with Buck doing the "understanding." Her

next best-seller was the non-fiction A Bridge for Passing

(1962) which was set in Japan, was partially autobiograph

ical, and also described the death of her husband. It was a

sentimental and melancholy book. Next was Buck's lone

novel of Korea, A Living Reed, which was discussed earlier.

Her final best-seller, The Three Daughters ofMadame Liang,

appeared in 1969 with all the ingredients of a standard

potboiler. Madame Liang grew up in the early days of the

revolution and now her three daughters return to the Com

munist controlled mainland where they encounter diverse

adventures. This last of Pearl Buck's novels about China

concentrated upon highly educated Chinese in marked de

parture from the peasantry of her earliest and most famous

work.

LinYutang

With five books and 562 points Lin Yutang ranks as the

second most influential interpreter of China for American

popular audiences through the medium of best-sellers. He

is the only native Asian member of the Big Five lineup of

super best-sellers. Like Pearl Buck, Lin Yutang's impact

was heightened by his presence in the United States at a

time of relatively high public interest in Asia, just before

and during the Second World War. In addition to the five

books which made best-seller lists, Lin wrote many others

and contributed numerous articles to The New York Times

Magazine and other periodicals. He also lectured widely in

the eastern U.S. on a variety of subjects pertaining to

China.

In many ways Lin complemented Buck nicely. They

25. Mary Johnson Tweedy, review of Come My Beloved in New York Times

Book Review, Aug. 9, 1953, p. 5.

10

were contemporaries, both of whom arrived in the United

States and rose to prominence in the mid-1930s. While Lin

represented in himself the educated upper-class Chinese,

Buck stood for the common peasant in her novels. Lin was

hardly a typical Chinese, if there has ever been such a thing.

He was, nevertheless, characteristic of the kind of person

who represents the people of one nation to those of an

other, especially in modern times. That is to say, he was a

person of privilege from one country, China, who became

quite familiar with the customs of another, the U.S., to

whom he then sought to present important aspects of his

native land. The result, influenced by class as well as cul

ture, was distortion as is commonly the case.

Lin was the son of a Chinese Christian clergyman and

born in Fukien Province in 1895. He was educated in mis

sion schools, mostly in Shanghai and, after a brief stint

teaching English, went to Harvard where he received an

M.A. and then to Leipzig University where he obtained a

Ph.D. in Philosophy in 1923. He then returned to China to

become a professor at Peita (China's most prestigious uni

versity) from 1923 to 1926. He was regarded as a radical in

these days, but he moved on to Amoy University as Dean

of the Arts College. He also served briefly as secretary to

Eugene Chen in the Wuhan Government in 1927. He was

with Academia Sinica in the early 1930s. Throughout this

period of his life in China Lin wrote steadily, mostly essays

and translations to and from English. He also edited a

humor magazine, Lun Yu. He was clearly well known in

scholarly circles in China, but he was not regarded there as

a major scholar in any field.

Lin's first best-seller in the United States was The

Importance of Living in 1937. This book purported to de

scribe a style of life, presumably Chinese, calculated to

provide a maximum amount of enjoyment. It was referred

to by some as an example of popular hedonism. 26 Its timing

was excellent as the war between China and Japan soon

aroused American interest in Eastern Asia. The book also

established Lin's reputation as a China expert, whereupon

he began to write about and comment on all kinds of things

pertaining to China. For example, he wrote about Chinese

drama for the entertainment section of the New York Times

and for the New York Times Magazine he prepared an article

comparing the Chinese and Japanese for the benefit of

American readers. ("The Japanese are busier but the

Chinese are wiser.")27 The majority of Lin's articles and

speeches in the late 1930s called for increased American

assistance for his beleaguered homeland. He occasionally

mixed in criticism of Western misunderstanding of China,

but it appears that he contributed not a little to that mis

understanding himself.

Lin loved to make predictions and to pontificate. In

March 1937 he declared that he didn't think Japan would go

to war with China. He also insisted that Communism could

not exist in China because the Chinese believed in a "per

26. For example, Robert F. Davidson, Philosophies Men Live By (New

York, Dryden Press, 1952). Davidson devoted one offourteen chapters in

this college text to "Popular Hedonism: The Cyrenaics, Epicurus and Lin

Yutang."

27. Lin Yutang, "As 'Philosophic China' Faces 'Military Japan,' " New

York Times Magazine, Dec. 27,1936, p. 5.

sonal government" and not in "systems." He was inclined

to stereotype his own countrymen. He promoted the

Chinese as lovers of peace. In reference to Chinese soldiers

in 1937 Lin stated that the Chinese soldier "has better

nerves than many European soldiers. His insensitivity to

pain is almost amazing. Life to him is cheap. "28 Later the

same year Lin clearly revealed his class origins in an article

about Chinese coolies in which he depicted Chinese work

ingmen in a condescending manner. 29 American readers of

this article were likely to conclude that Chinese houseboys,

rickshaw pullers, etc., were born to such occupations and

happy with them. His treatment differed not at all from the

common Western view that most Chinese were subhuman

and deserved to occupy positions of servitude.

As the war in China dragged on and American aid did

not materialize, Lin became increasingly bitter and hostile

toward U.S. policy. He began to express the view, widely

held before and since in China, that Western imperialism

and its ramifications were responsible for China's prob

lems. In a June 1941 article, Lin averred, "Years ago the

white man used to send gunboats to shoot Chinese, having

previously sent missionaries to make sure that their souls

would go to heaven when they were shot. That ought to

make it about even, according to the Occidental way of

thinking, but it does not make sense to an Oriental. Save

our bodies, but leave our souls alone. "30 In two non-fiction

books which made best-seller lists during World War II,

Lin Yutang brought this line of thinking to its culmination

and, in the process, started his own demise as a major

interpreter of China in the U.S.

The books were Between Tears and Laughter, published

in 1943, and Vigil of a Nation in 1945. The first of these

consisted in part of an attack on the United States and its

wartime allies for not assigning higher priority to the China

theater. Lin also excoriated Western imperialism and

materialism, accusing the U.S. and the West of patronizing

the Chinese. American reviewers vigorously denounced

Lin and his book for daring to question the priorities of the

war effort. Amerasia condemned the book for its rejection

of materialism and accused Lin of Gandhism which was out

of favor during a popular shooting war.3l The views ex

pressed in Between Tears and Laughter closely paralleled

those of Chiang Kai-shek whose famous book, China's

Destiny, appeared the same year. Both Chiang and Lin

essentially blamed Western imperialism for China's diffi

culties which could be overcome only by a revival ofConfu

cian values and virtues. Other American reviews of this

book were similarly unfriendly, some downright angry.

28. Lin Yutang, "Can China Stop Japan in Her Asiatic March?," New

York Times Magazine, Aug. 29,1937, p. 5. The depiction of Chinese and

other Asians (but especially Chinese) in this manner has been going on for

a long time. Akira Iriye quotes from a British newspaper at the beginning

of the twentieth century: "Think what the Chinese are; think of their

powers of silent endurance under suffering and cruelty; think of their

frugality; think of their patient perseverance, their slow dogged persis

tence, their recklessness oflife." Akira Iriye, "Imperialism in East Asia,"

in James B. Crowley, Modern East Asia: Essays in Interpretation (New

York, 1970), p. 145.

29. Lin Yutang, "Key Man in China's Future-the Coolie," New York

Times Magazine. Nov. 14,1937, pp. 8-9,17.

30. By-lined article in the New York Times. June 8, 1941, p. 19.

31. Unsigned review in Amerasia. 7:9 (Sept. 1943), pp. 286-289.

II

Vigil ofa Nation was based on a short trip to China and

was a virulent assault upon the Chinese Communists ac

companied by strong expressions of support for Chiang

Kai-shek and his "Nationalist" cohorts. This book drew

criticism from many persons including Edgar Snow whose

earlier works had sung the praises of the Chinese Com

munists. Vigil of a Nation was undoubtedly Lin Yutang's

most controversial book. Amerasia devoted an entire issue

to it 32 while scholarly criticism found expression in an

articie by Michael Lindsay from Yan'an,

stronghold.

33

Lin vehemently denounced his cntlCS whIle

some anti-Communist reviewers, like Freda Utley, ap

plauded Lin and his work. Lin Yutang's views in this book

presaged those of the so-called China lobby which was to

emerge shortly and contribute significantly to the

McCarthyite witch hunts of the early 1950s. Vigil ofa Nation

also marked the beginning of Lin's postwar role as an

anti-Communist publicist.

Despite the consonance of Lin's political position with

that of the emergent anti-Communist right in the U.S.,

there is no doubt that his general influence declined after

the establishment of the People's Republic of China in

1949. In 1954 Lin was lured to Singapore to become the first

chancellor of anew, privately funded university for

Chinese students. The initially advertised purpose of Nan

yang University was to countera.ct the Com

munism in all of Southeast ASIa. In thiS post Lm was

apparently as irascible as ever. He resigned before the

university opened its doors, citing obstruction from

quarters, most of it Communist inspired. After that, Lm

spent some time in the U.S., some in Hong Kong and

visited Taiwan frequently. He repeatedly refused a post m

the Taiwan government, but he remained a staunch

Communist. In the 1960s he developed a new typewnter

for the Chinese language and he brought out a monumental

Chinese-English dictionary in 1972.

34

By the time of his

death on March 26, 1976, his preeminence as an interpreter

of China to the American people had been all but for

gotten. .

Lin contributed significantly to the Amencan popular

image of China in the 1930s and the Second

War through his novels and non-fictIon books. ?IS

Chinese origins, Lin did not break down the cliched m

terpretations of his countrymen offered by. Pearl Buck.

Indeed, he reinforced these stereotypes as hiS characters,

particularly in fiction, were stock characters. The work of

Lin in English and its popularity in the U.S. suggest that

commercial success stems directly from a willingness to

adhere to existing images and prevailing stereotypes. Lin is

really unique among authors on this list as native interp

reter of his own people who, however, did them. a

service in the long run. Lin has never been admIred m

China and was often ridiculed by other Chinese as one who

had no qualifications to portray things Chinese to the rest of

the world. In the United States Lin was popular as long as

32. Vol. 9:5 (Mar. 9, 1945). The co-editors of Amerasia were Philip J.

Jaffe and Kate L. Mitchell.

33. Michael Lindsay, "Conflict in North China: 1937-1943," Far Eastern

Survey. 14:13 (July 4, 1945), pp. 172-176.

34. Chinese-English Dictionary ofModern Usage (Hong Kong, 1972).

he did not seriously challenge the existing notions about

China while playing the role of "wise and kindly

opher." Once he dropped this to attack the West and ItS

pretensions, his influence began to disappear.

John Masters

After Buck and Lin the other members of the "Big

Five" seem less interesting and significant, but they never

theless deserve brief mention, in part because they are still

active writers. John Masters placed eight books, mostly

with Indian locales, on American best-sellers list from

to 1961. He ranks second in number of books and fourth m

points with 586. He is the only author of the "Big to

concentrate on India and he has been, therefore, an Im

portant figure in establishing, pr?moting, nurturing. the

American popular image of IndIa. In to the

best-sellers, two of which were non-fictIonal autobiO

graphical accounts, Masters published five other novels

India seven novels with non-Indian settings, and one addi

tionai volume of autobiography. After the early 1960s his

popularity waned, perhaps as a result of

can interest in the subcontinent and the deromantlclZmg of

imperialism. Masters' later books were also invariably re

viewed unfavorably.

Like Buck and Lin, Masters was not brought up in the

United States. He was, in fact, born in India in 1914. His

father was a military officer, a career followed by John

Masters as well. He attended Sandhurst and served four

teen years in the British Army in India, endingwith Indian

independence in 1947. He then imr,nigrated to the U.S: to

begin a writing career. When intervIewed after the publIca

tion of his first book, Nightrunners of Bengal, m 1951,

Masters announced his intention of writing thirty-five

novels about the British experience in India. He then began

to tum out approximately one novel per year throughout

the 1950s. Masters is, still writing but seems to have aban

doned the ambitious plan for thirty-five books on India. He

has been much less of a public figure or pleader for special

causes than either Buck or Lin Yutang.

Although Masters wrote formula historical romances

set in India with European heroes, most of his earlier books

received praise from reviewers. He was sometimes com

pared favorably to Kipling, once for describing the "feroc

ity with which Oriental natives fought European troops so

long ago. "35 He was occasionally. as me!o

dramatic and no one saw him as a major literary figure WIth

prize winning potential. Some reviewers called his novels

loose and flamboyant and in the 1950s he was condemne.d

by some for his "lushly erotic scenes" and "crudely erotIc

episodes," obviously a major reason for the

larity. His autobiographical praise. for therr

sentimental treatment of the life of a soldier at a tIme when

such a life had romantic attraction in the U.S. He also

evoked nostalgia for the days of empire.

Masters' appeal and also his stereotyping are both

evident in pronounced form in Bhowani Junction

The central character in this novel is an Anglo-Indian wo

35. Harrison Smith, review of Nightrunners ofBengal, in Saturday Review,

Feb. 10, 1951, p. 13.

12

man who is wooed respectively by an Anglo-Indian man,

an Indian, and an Englishman. The Anglo-Indian man is

clumsy and foolish, but well-meaning. The Indian is shy

and reticent, but political. He refuses to kiss the girl before

marriage. The Englishman (a soldier) is decisive, cour

ageous, and virile. He and the heroine make love fre

quently and passionately, but in the end she returns to the

Anglo-Indian essentially because he is one of her own and

he needs taking care of. The Britisher and the Indian do

not. The time setting is 1946 as Britain prepares to leave

India. There is a story line revolving around attempts by

Indian Communists to stir up trouble and the efforts of

British and Indian officials to prevent it. The tale is rela

tively innocuous, but John Barkham called Bhowani Junc

tion the best novel of India since E. M. Forster's Passage to

India.

36

Masters' perspective, however, more closely re

sembles Kipling. The overall impression is that India is

ungovernable, especially by Indians.

Another frequently 0CCUI'I'iDg theme, largely in

fiction, is that Asian women are sexually sub

servient and available to Westerners. Tied to this

is the normaDy imp6cit notion tbat Asian women

prefer Western men as lovers, presumably be

cause they are more "manly," "virile," and less

chlldlike.

Masters' inftuence was of short duration. His treat

ment ofIndia and Indians was essentially that ofthe foreign

imperialist master. It is hard to imagine his books selling

well in India. In sum, the popular novels of John Masters

exemplify the impermanent but romanticized American

vision of India under British rule, replete with problems of

mostly Indian origin and potentially solvable by European

minds and vigor.

James Michener

James Michener's 5'12 books on Asia with 9841f2 points

rank him as a member ofthe super best-selling authors. His

books on Asia were published between 1947 and 1963,

although he has continued to write mammoth novels on

other subjects in the past two decades. Michener easily

ranks as one of the most popular authors in American

history. His writing career began with material on Asia and

he was for some time identified in the popular mind with

that continent. He frequently talked about "my part of the

world," by which he meant the Pacific, and he was briefly

considered an "expert" on just about anything pertaining

36. New York Times Book Review, Mar. 28, 1954, p. 1. Forster's famous

1924 book along with George Orwell's Burmese Days (1934) represent to

some extent opposite views of imperialism to those expressed by the

popular writers. Both concentrated on negative, even hostile, features of

British presence in India and Burma, but neither book made U.S. best

seller lists. Forster depicted in forthright manner and Orwell in exag

gerated fashion the overbearing condescension of white Europeans to

ward Asian "natives."

13

to any part ofAsia. Unlike Buck or Lin, he never became a

polemicist for causes relating to Asia, although he has

spoken out on some controversial social issues in the U.S.

in the last ten years.

Of the "Big Five" best-selling authors identified in this

study, Michener is the only one who spent his formative

years in the U.S. He was born in 1907 and raised near

Philadelphia. He spent some of his youth travelling in the

United States and graduated with honors from Swarthmore

College in 1929. In the 1930s he taught at prep schools and

also spent two years in Europe on wanderjahr. He received

a Masters Degree in Education from Colorado State Col

lege in 1936 and taught there and elsewhere, specializing in

social studies education. He was a visiting professor at

Harvard in 1940-41. He also did some editing for Macmil

lan and contributed articles to scholarly journals in his

specialty. During World War II Michener served in the

Navy and spent most of his time in the South Pacific. After

the war Michener published Tales ofthe South Pacific which

was a series of loosely connected stories set in wartime

among the islands of that part of the world. The book was

widely praised for its originality with Michener receiving

the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1948. Later the material in

this book became the enormously popular Broadway mu

sical and motion picture, South Pacific. Michener's fame

and success were assured.

None of his later worlc received as much critical ac

claim as Tales of the South Pacific, but his popularity re

mained high as he concentrated on stories and novels with

Asian or Pacific settings. The Bridges of Toko-Ri was orig

inally published in full in a single issue of Life (July 6, 1953)

which had, in fact, commissioned the novel. This short

novel of the Korean war thus had a vast readership, not

necessarily reflected in best-seller lists. Some of the scenes

were placed in Japan. Michener followed this with

Sayonara, a romance between an American Air Force offi

cer and a Japanese woman, in 1954; Caravans, the only

U.S. best-seller ever about Afghanistan in 1963; and

Hawaii, the first of his monumental novels, in 1959.

The last named book deserves inclusion in this study

because, despite the geographical setting, a majority of the

fiction characters are Asians. It is essentially a plotless tale,

panoramic in scope, covering respectively the Polynesian,

U.S. missionary, Chinese, and Japanese settlers of Hawaii.

The treatment is designed to be sympathetic to all, but the

characters, without exception, are stock. In the end the