Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Repair of Large Periapical Radiolucent Lesions of Endodontic Origin Without Surgical Treatment

Uploaded by

Fernando CordovaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Repair of Large Periapical Radiolucent Lesions of Endodontic Origin Without Surgical Treatment

Uploaded by

Fernando CordovaCopyright:

Available Formats

Blackwell Publishing IncMalden, USAAEJAustralian Endodontic Journal1329-1947 2007 The Authors; Journal compilation 2007 Australian Society of Endodontology?

? 20073641Case Report Repair

Periapical LesionsN. J. Broon et al.

of Large

Aust Endod J 2007; 33: 3641

C A S E R E P O RT

Repair of large periapical radiolucent lesions of endodontic origin without surgical treatment

Norberto Jurez Broon, DDS, MS; Eduardo Antunes Bortoluzzi, DDS, MS; and Clovis Monteiro Bramante, DDS, MS, PhD

Bauru Dental School, University of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil

Keywords non-surgical treatment, periapical lesion. Correspondence Dr Norberto Jurez Broon, Departamento de Endodontia da Faculdade de Odontologia de Bauru, Universidade de So Paulo, Al. Dr. Otvio Pinheiro Brisolla 9-75 CEP 17012-901, C.P. 73, Bauru, So Paulo, Brazil. Email: endobr1@hotmail.com; clobra@bol.com.br doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2007.00046.x

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to present two case reports of pulp necrosis and radiolucent periapical lesions, which were treated without surgical treatment. The rst was a mandibular molar with periapical lesion of endodontic origin extending towards the furcation in a 20-year-old woman, and the second affected a maxillary right lateral incisor with a large periapical lesion in a 22-year-old woman. The endodontic treatments were carried out in two sessions, with crown-down instrumentation, irrigation with 2.5% sodium hypochlorite and intracanal medication with calcium hydroxide paste. After 30 days, the root canals were lled with gutta-percha and Sealapex sealer by the lateral condensation technique. The clinical and radiographic examination after 1 year revealed complete repair. The appropriate diagnosis of lesions of endodontic origin and the treatment and obturation of the infected canals allowed complete repair of these large radiolucent periapical lesions without surgical treatment.

Introduction

Establishment of a periapical lesion is usually the host response to the invasion of the root canal system by microorganisms and their products. (1). The persistence of aetiological factors that cannot be eliminated from the root canal system by the host organism, such as microorganisms, dead cell remnants, foreign bodies and bacterial metabolic products, can result in a chronic inammatory process (2). At the cellular level, important cells acting in chronic inammation are macrophages and lymphocytes. Macrophages become multinucleated giant cells and are activated by mediators such as interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumour necrosis factor, which lead to bone resorption (3). Seltzer and Naidorff suggested that the incorrect handling of teeth with periapical lesions could cause intense postoperative pain (4). Leonardo and Leal afrmed that elimination of bacteria from the root canal is the most important factor for the successful treatment of periapical lesions, and the lack of regression of such lesions is generally assigned to the persistence of bacteria inside the root canal, with possibility of additional factors (5). Some lesions, however, may not be amenable to conservative

36

treatment and may require surgical treatment for total elimination of the pathologically involved tissues and attenuation of the periapical reaction (6).

Case report 1

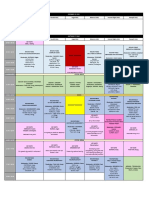

A 20-year-old female patient attended the Endodontic Clinic of the Unit of Dental Specialties of the Mexican Army. The reason for consultation was minor pain associated with the left mandibular rst molar. Upon questioning, the patient reported that the tooth was generally comfortable, yet with minor pain during mastication. Clinical examination revealed a tooth with a wide cavity open to the oral environment. Sensibility tests were negative, with minor discomfort to percussion and palpation. Radiographic evaluation demonstrated two roots and three root canals, which were wide and presented a slight curvature at the apical level. There was loss of continuity of the periodontal ligament and lamina dura and a periapical radiolucent lesion associated with both roots, measuring approximately 5 mm in diameter and completely involving the furcation region (Fig. 1). A diagnosis of chronic apical periodontitis extending to the furcation was

2007 The Authors Journal compilation 2007 Australian Society of Endodontology

N. J. Broon et al.

Repair of Large Periapical Lesions

Figure 1 Initial radiograph displaying the left mandibular rst molar and pathosis of the periapical tissues and furcation.

Figure 2 Radiographic image exhibiting complete lling of the root canals with calcium hydroxide paste (Calen PMCC).

made. This lesion was considered to be of endodontic origin. Periodontal evaluation did not reveal any signs of the lesion being associated with periodontal disease and the patient was otherwise in good health. There were no signicant medical complications. Treatment was performed with a rubber dam in place and preoperative asepsis was made with 1% sodium hypochlorite. Crown-down instrumentation was accomplished with abundant irrigation with 2.5% sodium hypochlorite (Viarzonit) at every change of instrument. Root canal preparation was made with K les (Flexo-File, Dentsply, Maillefer) #2040, with patency conrmed at every change of instruments, and Gates Glidden burs (Maillefer) #4, 3, 2. Final irrigation was performed with REDTA (Roth Int.) for 3 min followed by distilled water (for neutralisation), and then an intracanal medication with calcium hydroxide paste (Calen PMCC, S.S.White) was placed without overlling of the canals. The tooth was temporarily restored with Cavit-G (Espe) (Fig. 2). Clinical and radiographic evaluation was performed after 30 days. The patient was asymptomatic and the canals were obturated by the lateral condensation technique for the three roots canals, using gutta-percha (Hygenic) and sealer (Sealapex, Kerr). The radiograph taken at obturation revealed minimum repair of the chronic apical periodontitis and furcation area (Figs 3,4). At 60 days, the clinical and radiographic control demonstrated that the patient was asymptomatic and exhibited proper integrity of the periodontal tissues. Radiographically, there were areas of bone repair towards the centre of the lesion including the furcation area, minimum lamina dura at the alveolar crest and early reconstitution of the periodontal ligament space. Restoration was initiated by construction of an acrylic resin post (Fig. 5). At 90 days and 180 days,

Figure 3 Radiographic image at 30 days, during which the calcium hydroxide dressing (Calen PMCC) was maintained.

Figure 4 Final radiograph revealing obturation of the roots canals.

2007 The Authors Journal compilation 2007 Australian Society of Endodontology

37

Repair of Large Periapical Lesions

N. J. Broon et al.

Figure 5 Radiograph at 60 days, demonstrating early bone repair.

Figure 7 Radiograph at 180 days with good periapical and periodontal repair.

Figure 8 Radiograph at 270 days, displaying complete repair. Figure 6 Radiograph at 90 days, with prosthetic rehabilitation.

the patient displayed continued improvement with good periodontal condition. Radiographic evaluation exhibited repair of the bone tissues in the area, presence of lamina dura and integrity of the periodontal ligament space (Figs 6,7). The clinical and radiographic evaluation at 270 days and 1 year revealed a healthy tooth. Radiographic images demonstrated repair of the radiolucent periapical and furcation lesions (Figs 8,9).

Case report 2

A 22-year-old female patient attended the Endodontic Clinic of the Unit of Dental Specialties of the Mexican Army. The reason for consultation was completion of root canal therapy on the right maxillary lateral incisor, which

38

Figure 9 Radiograph at 1 year, revealing total integration and proper function of the dental structures.

2007 The Authors Journal compilation 2007 Australian Society of Endodontology

N. J. Broon et al.

Repair of Large Periapical Lesions

had been left unnished with an open cavity. The patient had reported minor pain with the presence of a sinus 8 months previously, yet in general terms she was asymptomatic. Upon questioning, the patient reported pain on mastication. Clinical examination conrmed the presence of a sinus with minor purulent exudate on palpation at the gingival marginal, as well as an open cavity in the tooth. Sensibility tests were negative, with slight discomfort on percussion and palpation. Radiographic examination revealed a seemingly straight root with a wide canal and thickening of the periodontal ligament space and a large radiolucent periapical lesion approximately 15 mm in diameter (Fig. 10). Treatment was performed under the same conditions as for the molar in Case 1. After 30 days, the root canal was obturated with guttapercha (Hygenic) and sealer (Sealapex, Kerr) using the lateral condensation technique. The patient was asymptomatic and the sinus had resolved (Fig. 11). After 90 days, the patient was asymptomatic and exhibited proper clinical integrity of the periodontal tissues. Radiographically, the right maxillary lateral incisor demonstrated initiation of bone tissue repair towards the centre of the lesion, minimal lamina dura, and early reconstitution of the periodontal ligament space and repair of the periapical lesion (Fig. 12). Radiographs at 180 days and 270 days showed progressive steady repair of the lesion (Figs 13,14). At 1 year, the patient exhibited healthy dental structures, a good periodontal condition periodontal and the absence of the original radiolucent periapical lesion (Fig 15).

Discussion

Proper root canal cleaning is fundamental in cases of teeth with radiolucent periapical lesions. Most of these lesions are diagnosed as lesions of endodontic origin; however, a differential diagnosis should include juvenile periodontitis and true endodontic-periodontal lesion (79). In Case 1,

Figure 11 Final radiograph of the right maxillary lateral incisor at 30 days after initiation of endodontic treatment.

Figure 10 Initial radiograph of the right maxillary lateral incisor demonstrating the large radiolucent periapical lesion.

Figure 12 Radiograph of the right maxillary lateral incisor at 90 days.

2007 The Authors Journal compilation 2007 Australian Society of Endodontology

39

Repair of Large Periapical Lesions

N. J. Broon et al.

Figure 15 Radiograph of the right maxillary lateral incisor at 1 year. Figure 13 Radiograph of the right maxillary lateral incisor at 180 days.

Figure 14 Radiograph of the right maxillary lateral incisor at 270 days.

the patient was asymptomatic and did not exhibit periodontal disease, despite the degree of bone loss in the furcation. Surgical intervention was not conducted, notwithstanding the extension into the furcation. Rocha considered that elimination of the antigen is the main factor for the immunopathological response (10). After elimination of the antigenic source, the organism is able to stimu40

late the immunologic system to induce repair. Ramos and Bramante stated that there is new formation of bone and cementum after regression of the apical inammatory process, which allows reinsertion of collagen bres (11). Root canal treatment, non-surgical, should always be the rst choice in cases of non-vital teeth with infected root canals. Souza et al. recommended intracanal medication using calcium hydroxide paste for non-surgical treatment of teeth with periapical lesions, reporting a success rate of 94% (12). According to Leonardo (13), and Leonardo and Leal (5), clinical procedures on teeth with periapical lesions should be performed in two or more treatment sessions. In both of the present cases, treatment was carried out in two sessions, with crown-down instrumentation, aided by irrigation with 2.5% sodium hypochlorite and intracanal medication with calcium hydroxide paste, in accordance with recommendations by Leonardo and Bezerra da Silva (14). Obturation was carried out at 30 days to allow the mechanism of action of the calcium hydroxide and PMCC. The patients' ages and the good general health could also have contributed to success. Rocha stated that patients with impairment of the immunologic system might display delayed or incomplete healing (10). Ramos and Bramante also believe that there are general factors that may inuence the repair of periapical lesions, including age, the presence of metabolic or nutritional disturbances, as well as the presence of systemic disease (11). Estrela and Figueiredo stated that the clinical and radiographic assessment for a period of more than 2 years is able to determine the nal treatment result (15). In the present

2007 The Authors Journal compilation 2007 Australian Society of Endodontology

N. J. Broon et al.

Repair of Large Periapical Lesions

cases, regression of the lesions by a non-surgical approach was evident after 1 year.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Captains CD Lady Eva Acevedo Tapia and Mariana Ortiz Vega (graduates of the Military Dental School, University of Army and Army Force, Mexico, DF) for their enthusiastic collaboration and support in the clinical phases of the procedures and assistance of the patient, to Captain CD Jos Mara Manzano Chaidez from the Unit of Dental Specialties of Mexican Army for his help in prosthetic rehabilitation, and to Gisele da Silva Dalben, from the Hospital for Rehabilitation of Craniofacial Anomalies of University of Sao Paulo, for her help in English language revision.

References

1. Estrela C, Figueiredo JAP. Periapical pathology. In: Estrela C, Figueiredo JAP, eds. Endodontics: biological and mechanical principles. So Paulo: Artes Mdicas; 2001. pp. 193245. 2. Siqueira JF, Dantas CJS. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of inammation. Rio de Janeiro: Medsi; 2000. 3. Trowbridge HO, Emling RC. Inammation: a review of the process. IL: Quintessence Books; 1993. 4. Seltzer S, Naidorff IJ. Endodontic are-ups bacteriological and immunological mechanisms. J Endod 1985; 11: 4644. 5. Leonardo MR, Leal JM. Endodontics: root canal treatment. 3rd ed. So Paulo: Mdica Panamericana; 1998.

6. Bramante CM, Berbert A. Endodontic surgery. So Paulo: Ed. Santos; 2000. 7. Hiatt W. Pulp-periodontal disease. J Periodontol 1977; 48: 598609. 8. Ruiz LF, Mendona JA, Estrela C. Interrelation between endodontics and periodontics. In: Estrela C, Figueiredo JAP, eds. Endodontics: biological and mechanical principles. So Paulo: Artes Mdicas; 2001. pp. 24991. 9. Simon JHS, Werksman LA. Endodonticperiodontal relations. In: Cohen S, Burns RC, eds. Pathways of the pulp. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1988. pp. 51330. 10. Rocha MJC. Microscopic and immunohistochemical study of apical periodontal cysts submitted or not to endodontic treatment, in relation to their non-surgical regression [PhD Thesis]. Bauru, So Paulo: University of So Paulo; 1991. 11. Ramos CAS, Bramante CM. Endodontics: biological and clinical bases. 2nd ed. So Paulo: Editora Santos; 2001. 12. Souza V et al. Non-surgical treatment of teeth with periapical lesions. Rev Bras Odont 1989; 46: 3946. 13. Leonardo MR et al. Histological observations of periapical repair in teeth with radiolucent areas submitted to two different methods for root canal treatment. Endodoncia 1995; 13: 907. 14. Leonardo MR, Bezerra da Silva LA. Topical medication between sessions, intracanal dressing in vital and non-vital pulp therapy I and II. In: Leonardo MR, Leal JM, eds. Endodontics: root canal treatment. 3rd ed. So Paulo: Panamericana; 1998. pp. 491534. 15. Estrela C, Figueiredo PJM. Endodontics: biological and mechanical principles. So Paulo: Artes Medicas; 1999.

2007 The Authors Journal compilation 2007 Australian Society of Endodontology

41

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- PLE 2019 - Medicine Questions and Answer KeyDocument24 pagesPLE 2019 - Medicine Questions and Answer KeydicksonNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- NCP (Rheumatic Heart Disease)Document2 pagesNCP (Rheumatic Heart Disease)Jenny Ajoc75% (4)

- 2019 International Symposium on Pediatric Audiology ScheduleDocument3 pages2019 International Symposium on Pediatric Audiology ScheduleEulalia JuanNo ratings yet

- The Chicken or The Egg? Periodontal-Endodontic Lesions : GHT EssDocument8 pagesThe Chicken or The Egg? Periodontal-Endodontic Lesions : GHT EssFernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- (Oncologysurgery) Graeme J Poston, Michael DAngelica, Rene ADAM - Surgical Management of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Di 1Document630 pages(Oncologysurgery) Graeme J Poston, Michael DAngelica, Rene ADAM - Surgical Management of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Di 1Marlene MartínezNo ratings yet

- Problem SetDocument2 pagesProblem Sethlc34No ratings yet

- Fernando shares photos and proposal from Europe tripDocument1 pageFernando shares photos and proposal from Europe tripFernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Irrigant Extrusion During Root Canal Irrigation A Systematic ReviewDocument20 pagesFactors Affecting Irrigant Extrusion During Root Canal Irrigation A Systematic ReviewFernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary Review 2 - Mode: Report - Unit 1 Genius: Nature or Nurture? Focus On Writing VocabulaDocument2 pagesVocabulary Review 2 - Mode: Report - Unit 1 Genius: Nature or Nurture? Focus On Writing VocabulaFernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Nickel-Titanium Versus Stainless Steel Instrumentation by Means of Direct Digital ImagingDocument5 pagesAnalysis of Nickel-Titanium Versus Stainless Steel Instrumentation by Means of Direct Digital ImagingFernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- Art. Extra de Pierre 2 de JulioDocument5 pagesArt. Extra de Pierre 2 de JulioFernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- Comparison of The Antimicrobial Activity of Six Irrigants On Primary Endodontic Pathogens PDFDocument3 pagesComparison of The Antimicrobial Activity of Six Irrigants On Primary Endodontic Pathogens PDFFernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- 109 - Roots Mounce 3Document5 pages109 - Roots Mounce 3Fernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Joen 2014 10 019Document4 pages10 1016@j Joen 2014 10 019Fernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- Incidence of Dentinal Cracks After Root Canal Preparation With Twisted File Adaptive Instruments Using Different KinematicsDocument4 pagesIncidence of Dentinal Cracks After Root Canal Preparation With Twisted File Adaptive Instruments Using Different KinematicsFernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- Vertical Root FracturesDocument11 pagesVertical Root FracturesVero AngelNo ratings yet

- 87116664Document5 pages87116664Fernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- Enf Pulpar e Incidencia Enf. Coronaria ELTONDocument5 pagesEnf Pulpar e Incidencia Enf. Coronaria ELTONFernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- PD F S May28 Journal of Endodontics 2012 SatoDocument4 pagesPD F S May28 Journal of Endodontics 2012 SatoFernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- Endo PerioDocument41 pagesEndo PerioFernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- Endo Perio2Document9 pagesEndo Perio2Fernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- Enf Pulpar e Incidencia Enf. Coronaria ELTONDocument5 pagesEnf Pulpar e Incidencia Enf. Coronaria ELTONFernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- 55305522Document9 pages55305522Fernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- Tratamiento Inicial Fase IVDocument6 pagesTratamiento Inicial Fase IVFernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- 21 MAYO The Influence of Dental Operating Microscope in Locating The Mesiolingual Canal OrificeDocument5 pages21 MAYO The Influence of Dental Operating Microscope in Locating The Mesiolingual Canal OrificeFernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- Microbiological Findings and Clinical Treatment Procedures in Endodontic Cases Selected For Microbiological InvestigationDocument6 pagesMicrobiological Findings and Clinical Treatment Procedures in Endodontic Cases Selected For Microbiological InvestigationFernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- Root Canal Treatment of Mandibular First and Second Premolars With Three Root CanalsDocument7 pagesRoot Canal Treatment of Mandibular First and Second Premolars With Three Root CanalsFernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- Real World Endo Sequence FileDocument24 pagesReal World Endo Sequence FileFernando CordovaNo ratings yet

- FJMCW Lahore MbbsDocument9 pagesFJMCW Lahore MbbsRayan ArhamNo ratings yet

- Hormone Levels For Fertility Patients1Document4 pagesHormone Levels For Fertility Patients1Kunbi Santos-ArinzeNo ratings yet

- Postpartum Hemorrhage Nursing CareDocument3 pagesPostpartum Hemorrhage Nursing CareClaire Canapi BattadNo ratings yet

- 2019 - E Danse, Dragean, S Van Nieuwenhove Et Al - Imaging of Acute Appendicitis For Adult PatientsDocument10 pages2019 - E Danse, Dragean, S Van Nieuwenhove Et Al - Imaging of Acute Appendicitis For Adult PatientsdaniprmnaNo ratings yet

- Formula of Vital Health IndicatorsDocument3 pagesFormula of Vital Health IndicatorsZyntrx Villas100% (1)

- Aconitum NapellusDocument12 pagesAconitum NapellusMuhammad Mustafa IjazNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Antara Abdominal Perfusion Pressure: (App) Dengan Outcome Post OperasiDocument17 pagesHubungan Antara Abdominal Perfusion Pressure: (App) Dengan Outcome Post OperasidrelvNo ratings yet

- Lec-1h-Excretory System ReviewerDocument12 pagesLec-1h-Excretory System ReviewerProfessor GhoulNo ratings yet

- Apollo: Reliability Meets Realism For Nursing or Prehospital CareDocument2 pagesApollo: Reliability Meets Realism For Nursing or Prehospital CareBárbara BabNo ratings yet

- Neonatal JaundiceDocument22 pagesNeonatal JaundiceNivedita Charan100% (1)

- Steroid Tapering and Supportive Treatment Guidance V1.0 PDFDocument1 pageSteroid Tapering and Supportive Treatment Guidance V1.0 PDFNthutagaol TrusNo ratings yet

- Dobutamine Drug StudyDocument5 pagesDobutamine Drug StudyAlexandrea MayNo ratings yet

- Understanding BenzodiazepinesDocument7 pagesUnderstanding BenzodiazepinesChris Patrick Carias StasNo ratings yet

- MODUL 1 FKG UnairDocument61 pagesMODUL 1 FKG UnairLaurensia NovenNo ratings yet

- Types of Studies and Research Design PDFDocument5 pagesTypes of Studies and Research Design PDFPaulina VoicuNo ratings yet

- ThesisDocument5 pagesThesisVictoria ManeboNo ratings yet

- Abdominoperineal Resection MilesDocument17 pagesAbdominoperineal Resection MilesHugoNo ratings yet

- Reading Task 1-Breast Cancer and The ElderlyDocument6 pagesReading Task 1-Breast Cancer and The ElderlyJats_Fru_1741100% (5)

- Adenoma Carcinoma SequenceDocument27 pagesAdenoma Carcinoma SequenceKhurshedul AlamNo ratings yet

- Cancer ScreeningDocument8 pagesCancer Screeninglakshminivas PingaliNo ratings yet

- Njala University: Bo Campus-Kowama LocationDocument32 pagesNjala University: Bo Campus-Kowama LocationALLIEU FB SACCOHNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes and Contributing Factors Among Pregnant Jordanian Women Attending Jordan University HospitalDocument8 pagesPrevalence of Gestational Diabetes and Contributing Factors Among Pregnant Jordanian Women Attending Jordan University HospitalManar ShamielhNo ratings yet

- Comparative Efficacy of SPONTANEOUS BREATHING TRIAL Techniques in Mechanically Ventilated Adult Patients A ReviewDocument6 pagesComparative Efficacy of SPONTANEOUS BREATHING TRIAL Techniques in Mechanically Ventilated Adult Patients A ReviewInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- E-Poster PresentationDocument1 pageE-Poster PresentationOvamelia JulioNo ratings yet

- Figure 3-1 Comparing Typical Effectiveness of Contraceptive MethodsDocument1 pageFigure 3-1 Comparing Typical Effectiveness of Contraceptive MethodsNuttiya WerawattanachaiNo ratings yet