Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mateen Talpur

Uploaded by

Muhammad FarhanOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mateen Talpur

Uploaded by

Muhammad FarhanCopyright:

Available Formats

INTRODUCTION

The addition of a new dimension to national politics by student political activism has compelled many to closely scrutinize this phenomenon and bring out the various backdrop factors which generate it. While in the Asian African countries the students remained the very central element in the anticolonial struggles, in the United States they kept themselves in the forefront of the civil rights movement and, also in the campaign against the Vietnam War. But even before, in the revolutions of 1848 in Germany and in Austria, in Czarist Russia and in the East European countries students spearheaded various revolutionary movements and were the torchbearers of modern ideas of liberty, socialism and equality of opportunity. While student movements are deemed important among the various social movements, student organizations, indeed, recruit students into active politics and socialize them. It is this fact of political socialization and its consequences which form the focal point of this enquiry. Student organizations are secondary groups and they also work as agents of political socialization. The membership of a secondary group provides a person very good apprenticeship for dealing with relationships in the political world. In the context of political participation the members of the group equip themselves with the skill, information, and predispositions that are necessary for it. Student organizations which are political groups of young men are established for the purpose of disseminating political values and as such carry on intentional manifest political socialization. Students and Politics Student organizations as we find them today in Kerala are of quite recent origin, with a history of only four decades or so. But this does not mean that Kerala students were not politically conscious at all before the 1950's. On the contrary there is enough of evidence to show that they have been politically active from the beginnings of the present century and the Quit India Movement of 1942 formed the apex of the student movement in Kerala as was elsewhere in India. The All India Students Federation and the Students Congress were in existence even before 1956 when Kerala became a political unit in its present shape. The student movement which had a nationalist tradition lost its focal point and got disintegrated after the dawn of freedom. In fact, a transformation in the student movement in Kerala could be found after 1947. There has been no unified student movement in Kerala after independence and the movement came to be increasingly politicized.

Even though they are rarely the source of political inquiry, there are more non-college youth than college students in the United States. Data show that roughly one-fourth of Americans do not enroll in formal schooling after obtaining a high school diploma, and-although four-year college graduation rates have been increasing over time--nearly three-fourths of Americans will not earn a college degree (Mastracci, 2003, Stoops, 2004). According to estimates, in 2000 there were roughly 15.4 million 18-25 Americans who had no college experience, a figure that accounts for roughly 55% of the 18-25 year old cohort (Lopez & Kolaczkowski, 2003). For a host of reasons including age, lack of tuition money, inadequate secondary schooling, reluctance to study, [and] discouragement from family and friends, college may not be a reality for a sizable portion of the citizenry. Thus, even though politicians and policy makers speak mainly of sending more people to college, a steady third of adults 25 and older have only finished high school (Uchitelle, 2000).

Since 18 year olds were first given the chance to vote in the 1972 elections, their turnout rates have declined considerably (save two departures to this trend in 1992 and 2004, see Levine & Lopez, 2002; Youth Voter). Concerned with the potential impact this pattern might have on the political system, non-profit organizations, funding agencies and academics have begun to allocate considerable resources to researching the civic participation of Americas youth. Two key findings to emerge from these studies have been that education and maturation are critical predictors of voting behavior for young people (Highton & Wolfinger, 2001; Lopez & Kolaczkowski, 2003; Milbrath & Goel, 1977; Teixeira & Rogers, 2000; Wattenberg, 2002; Wolfinger & Rosenstone, 1980). That is, being part of a college community and gaining life experiences as one grows both have been shown to increase the likelihood that younger Americans will vote.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Todorov The Notion of LiteratureDocument15 pagesTodorov The Notion of LiteratureSiddhartha PratapaNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Importance of RamadanDocument4 pagesImportance of RamadanMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Cambridge O'level Principle of Accounts SyllabusDocument23 pagesCambridge O'level Principle of Accounts SyllabusTalhaRehman100% (1)

- Sustainable Development Plan of The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesSustainable Development Plan of The PhilippinesZanter GuevarraNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 - Prokaryotic VS Eukaryotic CellsDocument3 pagesLesson 2 - Prokaryotic VS Eukaryotic CellsEarl Caesar Quiba Pagunsan100% (1)

- 00 B1 Practice Test 1 IntroductionDocument6 pages00 B1 Practice Test 1 IntroductionsalvaNo ratings yet

- (International Library of Technical and Vocational Education and Training) Felix Rauner, Rupert Maclean (Auth.), Felix Rauner, Rupert Maclean (Eds.) - Handbook of Technical and Vocational Educatio PDFDocument1,090 pages(International Library of Technical and Vocational Education and Training) Felix Rauner, Rupert Maclean (Auth.), Felix Rauner, Rupert Maclean (Eds.) - Handbook of Technical and Vocational Educatio PDFAulia YuanisahNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 - Understanding Consumer - Business Buyer BehaviorDocument48 pagesChapter 5 - Understanding Consumer - Business Buyer BehaviorxuetingNo ratings yet

- SynopsisDocument10 pagesSynopsisMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Naveed and ButtDocument5 pagesNaveed and ButtMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Main Page000Document5 pagesMain Page000Muhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Chapter No. 06 The Risk and Term Structure of Interest RatesDocument4 pagesChapter No. 06 The Risk and Term Structure of Interest RatesMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- SahibDocument45 pagesSahibMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- ObjectivesDocument10 pagesObjectivesMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Socio-Economic Causes and Impact of Exchange Marriage (Watta Satta) in Tribal Area of D.GkhanDocument3 pagesSocio-Economic Causes and Impact of Exchange Marriage (Watta Satta) in Tribal Area of D.GkhanMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Socio-Economic Causes of Watta Satta Marriages in Tribal AreasDocument3 pagesSocio-Economic Causes of Watta Satta Marriages in Tribal AreasMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Title Page Acknowledgement Table of ContentsDocument4 pagesTitle Page Acknowledgement Table of ContentsMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- AsDocument11 pagesAsMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: Mohammad Arshad Maje House#9.A Street#3 Block# X D.G.KhanDocument2 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Mohammad Arshad Maje House#9.A Street#3 Block# X D.G.KhanMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Muhammad Abdul RaufDocument1 pageMuhammad Abdul RaufMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Rosheen Feroz: Curriculum VitaeDocument2 pagesRosheen Feroz: Curriculum VitaeMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- To Whom It May Concern: Dated 20 September 2012Document1 pageTo Whom It May Concern: Dated 20 September 2012Muhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Desi Efu ReportDocument66 pagesDesi Efu ReportMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

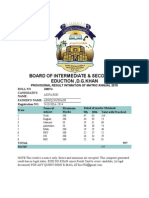

- Lazib Shah: Degree Year Marks/CGPA Board/ UniversityDocument1 pageLazib Shah: Degree Year Marks/CGPA Board/ UniversityMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Bank of Punjab: Internship Report ONDocument7 pagesBank of Punjab: Internship Report ONMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Matric Result Notice for Asifa Bibi with 557 Total MarksDocument1 pageMatric Result Notice for Asifa Bibi with 557 Total MarksMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Govt. Postgraduate College, D.G.Khan: Hope CertificateDocument1 pageGovt. Postgraduate College, D.G.Khan: Hope CertificateMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: Mohammad Arshad Maje House#9.A Street#3 Block# X D.G.KhanDocument2 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Mohammad Arshad Maje House#9.A Street#3 Block# X D.G.KhanMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Chapter No. 06 The Risk and Term Structure of Interest RatesDocument4 pagesChapter No. 06 The Risk and Term Structure of Interest RatesMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Muhammad Faisal HanifDocument2 pagesMuhammad Faisal HanifMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- People's Review of ADB, Sindh Rural Development Project DraftDocument46 pagesPeople's Review of ADB, Sindh Rural Development Project DraftMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- SaqlainDocument21 pagesSaqlainMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Zahid SynopsisDocument10 pagesZahid SynopsisMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Sajid Hussain: Degree Years Marks Board/ UniversityDocument1 pageSajid Hussain: Degree Years Marks Board/ UniversityMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Reference Rehmat UllahDocument5 pagesReference Rehmat UllahMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Reference Rehmat UllahDocument5 pagesReference Rehmat UllahMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Reference Rehmat UllahDocument5 pagesReference Rehmat UllahMuhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Bopps - Lesson Plan Surv 2002Document1 pageBopps - Lesson Plan Surv 2002api-539282208No ratings yet

- Organizational Behavior: Stephen P. RobbinsDocument35 pagesOrganizational Behavior: Stephen P. RobbinsPariManiyarNo ratings yet

- Technical Assistance NotesDocument6 pagesTechnical Assistance NotesJoNe JeanNo ratings yet

- Shahzad Zar Bio DataDocument2 pagesShahzad Zar Bio DatanoureenNo ratings yet

- Parameter For Determining Cooperative Implementing BEST PRACTICESDocument10 pagesParameter For Determining Cooperative Implementing BEST PRACTICESValstm RabatarNo ratings yet

- Holistic Teacher Development LAC SessionDocument2 pagesHolistic Teacher Development LAC SessionfrancisNo ratings yet

- The Snowy Day - Lesson Plan EditedDocument5 pagesThe Snowy Day - Lesson Plan Editedapi-242586984No ratings yet

- 8th Merit List DPTDocument6 pages8th Merit List DPTSaleem KhanNo ratings yet

- PHL 232 Tutorial Notes For Feb 26Document4 pagesPHL 232 Tutorial Notes For Feb 26Scott WalshNo ratings yet

- Luck or Hard Work?Document3 pagesLuck or Hard Work?bey luNo ratings yet

- Instructional SoftwareDocument4 pagesInstructional Softwareapi-235491175No ratings yet

- Theta Newsletter Spring 2010Document6 pagesTheta Newsletter Spring 2010mar335No ratings yet

- Diwan Bahadur V Nagam AiyaDocument168 pagesDiwan Bahadur V Nagam AiyaAbhilash MalayilNo ratings yet

- PHD & Master Handbook 1 2020-2021Document42 pagesPHD & Master Handbook 1 2020-2021awangpaker xxNo ratings yet

- The Law Curriculum - Ateneo Law School PDFDocument2 pagesThe Law Curriculum - Ateneo Law School PDFFerrer BenedickNo ratings yet

- Gaga Hand Dodgeball UnitDocument11 pagesGaga Hand Dodgeball Unitapi-488087636No ratings yet

- Chapter Two: Entrepreneurial Background, Trait and Motivation 2.1 The Entrepreneurial BackgroundDocument13 pagesChapter Two: Entrepreneurial Background, Trait and Motivation 2.1 The Entrepreneurial Backgroundsami damtewNo ratings yet

- Statements of Purpose Guidelines and Sample EssaysDocument51 pagesStatements of Purpose Guidelines and Sample Essaysyawnbot botNo ratings yet

- UCL Intro to Egyptian & Near Eastern ArchaeologyDocument47 pagesUCL Intro to Egyptian & Near Eastern ArchaeologyJools Galloway100% (1)

- Template - Letter of Undertaking (For Students)Document2 pagesTemplate - Letter of Undertaking (For Students)Vanshika LambaNo ratings yet

- Vanessa JoyDocument23 pagesVanessa JoyAstigBermudezNo ratings yet

- 221 Meeting Minutes FinalDocument157 pages221 Meeting Minutes FinalKrishna Kumar MishraNo ratings yet

- Enrolment Action Plan Against COVID-19Document4 pagesEnrolment Action Plan Against COVID-19DaffodilAbukeNo ratings yet