Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Amafter911 Stampala

Uploaded by

majcek13Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Amafter911 Stampala

Uploaded by

majcek13Copyright:

Available Formats

RUBRIK

TEMA: AMERICAN ISSUES

Thomas rvold Bjerre Center for American Studies, SDU

American Literature after September 11

The cataclysmic terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 played like a well-known Hollywood movie but with real-life tragic consequences. In the years since, Hollywood and other parts of popular culture have attempted to make sense of the tragedy. While 9/11 was quickly incorporated into American music, by artists like Neil Young and Bruce Springsteen1, and the movie industry spurted out the propagandistic and heroic TV-lm DC 9/11: Time of Crisis in 2003, it would be almost four years before the rst novel about 9/11 emerged. We already have the ofcial version of 9/11. Its called The 9/11 Commission Report and has been praised by, among others, John Updike as a masterpiece produced by a committee, comparable only to the King James Bible. It also became a bestseller, selling more than a million copies in the rst four months. However, many have questioned the report, and in any case, as we all know, many prefer ction to the truth, especially in such complex issues as this one. So the story of 9/11 has become many different stories, stories that all play a part in the struggle to become the dominant narrative about 9/11. Unlike, for instance, the Vietnam War or other crises, 9/11 took place within a few hours. The ramications of the attacks, however, have continued to reverberate in American culture ever since. And the US-led wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have been direct consequences of the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington DC. So I think it is important that we try to make sense of the way 9/11 has been absorbed into American culture. Not just the way it has been used and abused by politicians, but the more quiet way it has been picked up by songwriters, poets, lmmakers, the way it has become part of the language, and the way serious writers of ction have handled the unthinkable. As Peter Schepelern has argued, talking about lm, effective ction inuences the formation of public opinion and shapes our general perception of things (Schepelern 44) That too is the case with literature, of course.

48 | ANGLO FILES | Februar 2009

RUBRIK

TEMA: AMERICAN ISSUES

However, in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, it did not seem likely that there would ever be literature dealing with the horric attacks. The British writer Martin Amis perhaps best summed up the general attitude among writers immediately after the terrorist attacks: After a couple of hours at their desks, on September 12, 2001, all the writers on earth were reluctantly considering a change of occupation, he wrote in an essay in The Guardian. A novel, he contin-

ued, is politely known as a work of the imagination; and the imagination, that day, was of course fully commandeered, and to no purpose . The so-called work in progress had been reduced, overnight, to a blue streak of pitiable babble (Amis). However, there still seemed to be a need for what the novelist could offer. In a September 23, 2001 essay in The Observer titled The need for

50 | ANGLO FILES | Februar 2009

RUBRIK

TEMA: AMERICAN ISSUES

novelists, Robert McCrum points to the paradox that its the imaginative writers who have provided the most trustworthy response to the dreadful irruption of horryfying reality and points to contemporary masters like Ian McEwan and Paul Auster, who have come up with the words of comfort and clarity we crave in the midst of shock and desolation (McCrum). But the novelists could no longer rely on old and comfortable habits. 9/11 demanded that they rise to the challenge, at least according to James Wood who in his essay in The Guardian offers a critique of the contemporary American novel, which he describes as a watered-down DeLilloinuenced display of knowledge, but without a beating heart: Knowing about things has become one of the qualications of the contemporary novel, he states. The result in America at least is novels of immense self-consiousness with no selves in them at all, curiously arrested and very brilliant books that know a thousand things but do not know a single human being. The writers he has in mind are people like Jay McInerney, Bret Easton Ellis, Thomas Pynhon, Dave Eggers, and David Foster Wallace but also post-colonial writers like Salman Rushdie and Zadie Smith. Pointing out the characteristics of many of these writers, Wood hopes that the events of 9/11 will bring about the end of what he calls hysterical realism, a type of ction which is characterized by a fear of silence. This kind of realism is a perpetual motion machine that appears to have been embarrassed into velocity. Stories and sub-stories sprout on every page. There is a pursuit of vitality at all costs. Instead, Wood hopes for novels that have space for the aesthetic, for the contemplative, for novels that tell us not how the world works but how somebody felt about something indeed how a lot of different people felt about a lot of different things (Wood Tell me). So where does the novelist t into all this? In the much talked about essay In the Ruins of the Future in Harpers, Don DeLillo offers the pessimistic view that Today, again, the world narra-

tive belongs to terrorists (33). DeLillos response was particularly interesting, and met with great attention, partly because of his canonical status in American letters, but also because he, unlike any other American novelist, has spent his carreer probing issues like terrorism and paranoia in American culture. In fact, DeLillos bleak statement echoed his novel Mao II (1991), in which the writer and the terrorist were linked. This is the writer Bill Gray speaking: Theres a curious knot that binds novelists and terrorists . Years ago I used to think it was possible for a novelist to alter the inner life of the culture. Now bomb-makers and gunmen have taken that territory. They make raids on human consciousness. What writers used to do before we were all incorporated . Were giving way to terror, to news of terror, to tape recorders and cameras, to radios, to bombs stashed in radios. News of disaster is the only narrative people need. The darker the news, the grander the narrative. (41-42) And later in the novel, the terrorist sympathizer George Haddad is talking to Bill: In societies reduced to blur and glut, terror is the only meaningful act. Theres too much everything, more things and messages and meanings than we can use in ten thousand lifetimes. Inertia-hysteria. Is history possible? Is anyone serious? Who do we take seriously? Only the lethal believer, the person who kills and dies for faith. Everything else is absorbed . Only the terrorist stands outside. The culture hasnt gured out how to assimilate him. Its confusing when they kill the innocent. But this is precisely the language of being noticed, the only language the West understands. The way they determine how we see them. The way they dominate the rush of endless streaming images. (157-58) So after 9/11, when the discussions of Mao II had become bloody reality on American soil, any writer of serious ction had to ask him/herself how to become heard amidst the terrorists language of being noticed? And what should a serious writer write about? DeLillo answers the last question in his essay In the Ruins of the FuANGLO FILES | Februar 2009 | 51

RUBRIK

TEMA: AMERICAN ISSUES

ture: The narrative ends in the rubble, and it is left to us to create the counter-narrative, he writes (34). This counter-narrative will have to constist of seemingly trivial stories of everyday lives affected in one way or another by the attacks, stories that take us beyond the hard numbers of dead and missing and give us a glimpse of elevated being. (34). According to DeLillo, we need these stories to set against the massive spetacle that continues to seem unmanageable, too powerful a thing to set into our frame of practiced response (35). I will return to DeLillo shortly. But let us now take a closer look at some of the American 9/11 novels that have arrived within the past four years novels that contribute to the way Americans, the way we all, perceive and think about 9/11. Let me start with a list of novels that can be labelled 9/11 stories: Philip Beard: Dear Zoe (March 2005) Jonathan Safran Foer: Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (April 2005). Lynne Sharon Schwartz: The Writing on the Wall (May 2005) Reynolds Price: The Good Priests Son (June 2005) Jay McInerney: The Good Life (January 2006) John Updike: Terrorist (June 2006) Ken Kalfus: A Disorder Peculiar to the Country (July 2006) Jess Walter: The Zero (September 2006) Don DeLillo: Falling Man (May 2007) Andre Dubus III: The Garden of Last Days (June 2008) This is not necessarily a complete list. There are other novels, such as Paul Austers The Brooklyn Follies (December 2005), Claire Messuds The Emperors Children (August 2006), and Philip Roths Exit Ghost (October 2007) that allude to 9/11 in minor ways. And then there are distinguished novels like Mohsin Hamids The Reluctant Fundamentalist (April 2007) and Joseph ONeills Netherland (May 2008) very much 9/11 novels that take place in the US, but since

52 | ANGLO FILES | Februar 2009

they are written by non-Americans, I will not include them in here they are, however, very recommendable and ne examples of the power of transnational ction. As we can see, the list of American writers is comprised of both old and young, of well-established, canonical writers like Updike, Price, and DeLillo, of up-and-coming writers like Foer and Kalfus, and those in-between. What is perhaps most interesting is that only one woman has so far written about 9/11 and its aftermath. And in fact, the issue of masculinity plays an important part in several of the novels, particularly The Good Life, Terrorist, A Disorder Peculiar to the Country, The Zero, and Falling Man. But despite the gender and age differences, many of these novels have several things in common: All of them focus on private, individual destinies. Rather than trying to see the terrorist attacks in a larger, global perspective, they focus on how the events inuenced the lives of a few American people. A minor exception here is Jess Walters The Zero, an absurd political satire in which a heroic New York cop wakes up shortly after 9/11, having unsuccessfully tried to kill himself. Brian suffers from memory gaps, which become part of the novels narrative structure, thereby affecting the reader as well. Brian works as an ofcial guide for celebrities that want a tour of Ground Zero. He is then (perhaps?) hired by the Documentation Department, a subagency of the Ofce of Liberty and Recovery, which has to analyse every piece of paper that spread over the city when the towers fell. Brian begins to realize that he is caught up in a covert and possible illegal business. As a backdrop to Brians story, Walter displays how the unnamed mayor The Boss cashes in on the tragedy, and how the national grief evolved into a commercial nationalism used for political and nancial gain. But let us return to the theme that unites the novels: often, the novelists use personal crises (divorces, traumas, etc) to reect the larger, national crisis. Different as they are in tone, The

RUBRIK

TEMA: AMERICAN ISSUES

Good Life, A Disorder Peculiar to the Country, and Falling Man are all stories about broken-up marriages. It can even be said that these personal crisis often overshadow the larger national crisis. Jay McInerney was one of the young stars on the literary scene in the 1980s. Together with his buddy Bret Easton Ellis he gave a satirical portrait of the hedonistic lifestyle in Manhattan in the 1980s. But while The Good Life still centers around Manhattans upper-class, the tone is much more subdued, serious, almost sacred. This very traditional story tells of two married Manhattan couples. Both marriages have become routine, and the terrorist attacks serve as a catalyst. Luke who makes it out of the World Trade Center alive meets Corinne on the street.

They both start volunteering at a soup kitchen for rescue workers, they fall in love and start an affair. Ken Kalfus A Disorder Peculiar to the Country is completely free of McInerneys sombre and reverential tone; in fact the novel is a shamelessly funny social satire, chronicling a bitter Manhattan divorce. Watching the collapse of the World Trade Center where her husband Marshall works, Joyce has to suppress a laugh amidst her colleagues. And Marshall, who cancelled his meeting at the last minute, is thrilled when he

ANGLO FILES | Februar 2009 | 53

RUBRIK

TEMA: AMERICAN ISSUES

hears of the Flight 93 crash because his wife was supposed to be on that plane. When they see each other alive that afternoon, both are bitterly disappointed, and the divorce proceedings soon turn very ugly. Don DeLillos Falling Man is a subdued, almost mufed story of Keith, who walks out of the rubbles and arrives at the doorstep of his ex-wife Lianne. The two try to mend their relationship and care for their son, who has become paranoid and keep searching the skies for signs of the man the media call Bill Lawton. But Keith has trouble committing. He starts seeing a fellow survivor from the Towers, Florence, and he becomes obsessed with playing poker professionally. Even the novels that do not focus on brokenup marriages still attempt to juxtapose the national catastrophe with personal tragedy or trauma. In Philip Beards Dear Zoe, the teenage girl Tess writes letters to her baby stepsister who was killed in front of the family home in a car accident on September 11. Tess was supposed to look after her three-year-old sister but became distracted by the horrible news on TV. In The Writing on the Wall, the terrorist attacks spring open the protagonist Renatas old traumas, which she is then forced to face: her twin sisters mysterious drowning, her fathers fatal car accident, and her mothers lapse into insanity. In The Good Priests Son, the protagonists father, an 80-year-old wheelchair-bound Southern preacher, admits that the only person he ever loved was his son Gabe, the protagonists brother who was killed in a hunting accident at age 18. All these years later, the old father still cannot get over the loss: The end of the World Trade Center in New York is nothing at nothing compared to the death of that one child (Price 123). Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close is a playful and very postmodern story, certainly an example of the hysterical realism that James Wood hoped would disappear in the wake of 9/11. It

54 | ANGLO FILES | Februar 2009

is the story of 9-year-old Oskar who lost his father in the World Trade Center attacks, but the story soon begins to focus on another major historical trauma, that of Oskars grandparents and their experience of the rebombing of Dresden. This last aspect is really the only global perspective that any of these novels offer, and it would be hard to argue that World War II is directly connected to 9/11. There are several examples of writers that try to portray the terrorists. The rst was John Updike, who passed away just this week. His deliberately provocative and fast-paced thriller (an unlikely genre for Updike) Terrorist tells the story of eighteen-year-old Ahmad, the son of an IrishAmerican mother and an Egyptian father, who grows up in northern New Jersey and turns to Islam at the age of eleven. He becomes drawn into a group of Islamic fundamentalists and ends up planning to blow up the Lincoln Tunnel. In Falling Man, DeLillo devotes a few brief chapters to Hammad, one of the terrorists preparing their attacks, rst in Hamburg then in Florida. Like Updikes troubled teen, Hammad is torn between the religious teachings of Mohamed Atta and the seductive lures of the Western world. But Hammad never becomes a fulledged character, and it seems DeLillo uses him more as a provocative link to the protagonist Keith, suggesting that the Islamic terrorist and the white, middle-class American both live their lives according to the same belief in ritual and restriction. In Keiths case, he becomes increasingly drawn into the world of professional poker with its strict set of rules and regulations. As Laura Miller suggests, this link between Hammad and Keith is perhaps DeLillos comment on the effects of the sacred male bonds, the brotherhoods that take up more and more space in our culture (Miller). As DeLillo writes about Keiths passion for poker: they loved doing this, straight faced, because where else would they encounter the kind of mellow tradition exemplied by the needless utterances of a few archaic words (99). DeLillo does not answer the question, but the

RUBRIK

TEMA: AMERICAN ISSUES

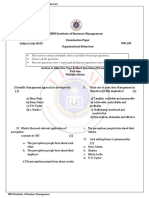

En del af hungersndskulpturen i Boston

ANGLO FILES | Februar 2009 | 55

RUBRIK

TEMA: AMERICAN ISSUES

inclusion of Hammad in the novel certainly puts Keiths unquestioning adherence to discipline and purity in an unsettling perspective. Both Updike and DeLillo seem drawn to the clash between the strict Islamic traditions and the hedonistic culture of the US experienced by the young jihadists. Updikes young Ahmad has been warned that women are animals easily led and he can see for himself that the high school and the world beyond it are full of nuzzling blind animals in a herd bumping against one another, looking for a scent that will comfort them. But talking to one of the few girls in school who takes an interest in Ahmad, he must try extra hard not to let his hormones get the better of him: The tops of her breasts push up like great blisters in the scoop neck of the indecent top that at its other hem exposes the fat of her belly and the contour of her deep navel. He pictures her smooth body, darker than caramel but paler than chocolate, roasting in that vault of ames and being scorched into blisters (Updike 10, 9). DeLillo, as always, is much more frank than the polite Updike, as in this brief sentence about Hammad: Late one night he had to step over the prone form of a brother in prayer as he made his way to the toilet to jerk off (80). And nally, in the most recent 9/11-novel, The Garden of Last Days, Andre Dubus III devotes more than 500 pages to a story revolving around the The Puma Club for Men, a Florida strip club, where one of the 9/11 hijackers, Bassam al-Jizani a ctionalised character encounter and becomes obsessed with the Florida stripper April. While the novel is as much about April and other characters, much of it focuses on Bassams relentless internal conict between his spiritual discipline and his sexual urges. Another interesting aspect in the novels is the way most of them focus on New York. This is no surprise, since the largest attack took place in New York and since most of the writers are themselves New Yorkers. I do want to point

56 | ANGLO FILES | Februar 2009

to a small tendency that is apparent in two of the books that of contrasting New York the loud, crazy, traumatized metropolis with the South, traditionally the image of laid-back tradition and old manners. The South has always held a unique position in American culture. This is based on the commonly accepted idea that the South as a region and as a culture is distinctly different from the rest of the US. The otherness or exceptionalism, depending on who you ask, is grounded in historical events the southern states were the slave states that fought on the losing side of the Civil War (1861-65), a loss and a subsequent period of Reconstruction/occupation that served to create a strong sense of unity among southerners and that led to a strong and stubborn regional pride that is still felt today. The South is also synonymous with certain characteristics or values, perhaps more so than any other region in the country a greater attention to the past, an acceptance of mans niteness, his penchant for failure, a tragic sense . a religious sense, a closeness to nature, a great attention to and affection for place, a close attention to family, a preference for the concrete and a rage against abstraction (Hobson 3). These values become important in two of the novels, Prices The Good Priests Son and McInerneys The Good Life which momentarily retreat from the chaos of a wounded New York and to the tranquillity of the Southern countryside. In Prices novel, the 53-year-old protagonist Mabry Kincaid is on a plane returning from Europe to New York when he learns of the attacks. Realizing that he will be unable to reach his Manhattan apartment, Mabry decides to return to his small hometown in North Carolina, where his old father still lives. As a Southernerturned-New Yorker, Mabry suffers from many of the conditions of the modern world: he is lonely and rootless, and to top it off, his body is decaying. Returning to the South is both a way of escaping the current tragedy, but as it turns out, Mabry has plenty of old demons awaiting him at home. However, as a male version of the Scarlett OHara that he admires, Mabry gradually nds

RUBRIK

TEMA: AMERICAN ISSUES

strength in the Southern soil and eventually recovers his Southern identity, which again helps him nd meaning in the chaotic presence that surrounds him. Mabrys rekindled love for the South serves as a stark contrast to his newfound disgust for New York. Returning briey to his Manhattan apartment, Mabry realizes that hed never enter that door again, struck as he is with the death that hung enormous above him his countrys inevitable doom somehow inscribed around him in the air they were breathing (209). In The Good Life, which mostly takes place in Manhattan, Luke brings his suicidal teenagedaughter back to his mother in Tennessee. Here the South comes to serve as a haven, a place of regeneration and of real values opposed to the supercial role-playing in Manhattan. Even though Luke wasnt one of those for whom southernness was a religion, for whom nostalgia was an emotion more primal than lust, (278) he still feels a strong connection to the region. In

an important scene ripe with Southern Gothic undertones, Luke, who is in love with Corinne and plans to leave his wife Sasha, sits in a Civil War graveyard at night, listening, waiting for the dead to communicate. It seemed worth a shot. No one else was going to tell him what to do, and surely these men knew something about duty and honor (289-90). Like a true Southerner, Luke respects the wisdom of his elders and tries to gain their advice. And, more importantly, the daughter Ashley brings back to New York a newfound pride in her Southern roots. At the annual pre-Christmas lunch at a fancy New York restaurant, a choir performs Christmas carols and then sings Battle Hymn of the Republic. When they follow up with the Southern hymn Dixie, Ashley, whod spent most of lunch trying to shrink under the table, surprises everyone by rising and standing to attention. When she urges her father to do the same, Sasha, always keeping the right Manhattan appearances, can only shake her head almost imperceptibly, forcing a smile of tolerant indulgence, and bitterly

ANGLO FILES | Februar 2009 | 57

RUBRIK

TEMA: AMERICAN ISSUES

commenting Well, arent we the rebels, before refusing to join her family with the acid remark: Theres a time and a place (330-31). This was an outline of some of the general tendencies in the genre known as 9/11 ction. I would like to end this talk by going into a little more detail with what I think is, so far, the best and most ambitious novel about 9/11 and its aftermath in American culture: Don DeLillos Falling Man. In the years after the attacks, many felt that DeLillo was the obvious writer to take on the event. As Laura Miller argues, the attacks themselves seemed DeLilloesque a freakish juxtaposition of big, glossy, spectacular images and the confusion, fear and death we knew lay behind them (Miller). This is very much the stuff DeLillos novels are made of, and the expectations to Falling Man were high, to say the least. I think many of us were waiting for a sweeping Underworldlike treaty on the subject (even the cover of Underworld seemed prophetic after 9/11!), but Falling Man is ultimately closer to DeLillos slim, ethereal novel The Body Artist (2001). As already mentioned, the story centers around Keith and Lianne, a divorced couple who try to mend their relationship after the attacks. DeLillo opens the novel in the immediate chaotic aftermath of the towers collapse: It was not a street anymore but a world, a time and space of falling ash and near night (3). And the last breathtaking pages of the novel describe the plane hitting the rst tower, rst seen from Hammads point of view, which then at the moment of impact changes seamlessly to Keiths point of view. This circular structure of beginning and ending with the disaster suggests that there is no escape from this tragedy, at least not for the characters. This is enforced by the repeated returns to the descriptions of 9/11 that appear randomly throughout the novel. This can be seen, perhaps as a comment on the endless stream of images fed to us by the news media in the aftermath of the attacks, but also, of course, as a way of in58 | ANGLO FILES | Februar 2009

scribing the characters traumas, their inability to escape the disaster, into the very structure of the text. As Laura Frost notes in her review, the fact that we do not experience the actual attack until the very end of the novel, is a narrative move that imitates the structure of psychological trauma: numbness in the moment itself followed only later by delayed understanding (Frost). The novels title refers to a performance artist who suspends himself in midair, mimicking the shocking images of people jumping and falling from the towers. But the title also refers to Keith, who is in every sense of the word falling. This is Keith watching the second tower fall: That was him coming down, the north tower (5). Traumatized by the events, he is in emotional collapse, he becomes more and more distant to his family, and tries to lose himself and the memory of the attacks through poker playing. And while Keith is actively working to escape his own memories, his wife Lianne is struggling not to lose hers. Terried that she has inherited her fathers Alzheimers, Lianne tries to calm her fears by working with a group of old people suffering from Alzheimers. There is a less noble reason for this, however. By getting to know these old people, by witnessing the gradual decline of their minds, Lianne somehow feels closer to her own father whose dementia-driven suicide when she was young still haunts her. While the reader may suspect some sort of happy ending in store for Keith and Lianne, there are none of the tender touches of McInerneys The Good Life to be found in Falling Man. Instead of rekindling their love, Keiths return to Lianne, as James Wood notes, does not so much heal old wounds as add a new one to the old: The marriage must now accommodate Keiths incommunicable memories, his drifting trauma, the hours he spends at Florence Givenss apartment (Wood Black Noise). As he did in Mao II, DeLillo has characters debate the nature of terrorism. This time it is Li-

RUBRIK

TEMA: AMERICAN ISSUES

annes mother Nina and her German lover Martin. In the 1970s, Martin was part of a radical group, Kommune One that, perhaps, resorted to terrorism in their protest against the West German state. So Martin offers provocative sympathies for the urge behind the attacks: Werent

the towers built as fantasies of wealth and power that would one day become fantasies of destruction? he asks. You build a thing like that so you can see it come down. The provocation is obvious. What other reason would there be to go so high and then to double it, do it twice?

ANGLO FILES | Februar 2009 | 59

RUBRIK

TEMA: AMERICAN ISSUES

You are saying, Here it is, bring it down (116). And despite Martins sympathies with the terrorists, Lianne touches upon the heated and controversial debate regarding terrorism, religion, and race when she thinks to herself: Maybe he was a terrorist but he was one of ours, she thought, and the thought chilled her, shamed her one of ours, which meant godless, Western, white (195). One of the biggest surprises in the novel is that DeLillo does not focus on the medias role in 9/11 and its aftermath. Coming from a writer who has written obsessively, and with great insight, about the power of mass media in constructing our world, of seductive and deceptive images, in novels like White Noise, Mao II, and Underworld, the absence of media in Falling Man is striking, to say the least. We do get brief images of Keith and Liannes son Justin in front of the TV, staring helplessly into the glow, a victim of alien abduction (117). And in a scene where Keith and Lianne talk about their son, the TV glows mutely in the background: There was stock footage on the screen of ghter planes lifting off the deck carrier. He waited for her to ask him to hit the sound button (131). But the role of the media in the novel remains just that, mute. Laura Frost suggests that the absence is an attempt from the novelist to wrest 9/11 back from the media. Because media bombardments leaves no room for or trumpets the novelists embellishment? (Frost). Many critics have faulted the novel for lacking a heart, or as James Wood puts it: a book that is all limbs but nally no living, pulsing center (Wood Black Noise). This is often an accusation against DeLillos books and his style, which is admittedly formal and theatrical, his characters are vague and speak an implausible dialogue. But I would argue that the lack of a living, pulsing center is exactly the point in Falling Man. DeLillos stunned style seems to perfectly match the dazed, shell-shocked state of mind of the characters, which is hard not to see as a general

60 | ANGLO FILES | Februar 2009

comment on the state of the union in general. An impending sense of quiet doom pervades the novel, which is a refreshing respite from the heroic sentimentalism that bogs down so many of the 9/11 narratives, especially in lm and music. While Keith certainly lives up to the image of the corporate he-man, his role is anything but heroic in the novel. His development never reaches a satisfying peak. At the end of the novel Keith has reached a point where he seems to have found a way of being that enables him to function, but when he thinks of himself, it is unshaped, a false memory or too warped and eeting to be false. Keith wonders if he was becoming a self-operating mechanism, like a humanoid robot that understands two hundred voice commands, farseeing, touch-sensitive but totally, rigidly controllable (228, 226). So rather than becoming a full human being again, Keith has managed to leave himself behind altogether. As for Lianne, she comes to the recognition that She was ready to be alone, in reliable calm, she and the kid, the way they were before the planes appeared that day, silver crossing blue (236). DeLillos characters are just a few of the many New Yorkers who remain stuck in a state of trauma, unable to nd any sort of redemption or regeneration in the aftermath of the attacks. People can attempt to do good things, like attending anti-war rallies, but mostly they just act human: selsh and random. Falling Man is a post-traumatic snapshot of a nation living in the shadows of no towers, to borrow Art Spiegelmans title. In this way, Falling Man places itself between the sanctimoniousnes of i.e. The Good Priests Son and The Good Life and the acidic and subversive satire of A Disorder Peculiar to the Country and The Zero. It still needs to be seen whether an American writer will attempt to see 9/11 in a larger, global perspective. So far, US writers have retreated to the domestic life, licking the nations wounds by focusing solely on the emotional and existential struggles of 9/11. This certainly needed to

RUBRIK

TEMA: AMERICAN ISSUES

be done, and it has resulted in a number of ne novels. However, it is not until American writers dare to lift their heads and look beyond the nations borders that we may get the ultimate 9/11 novel, one that focuses both on the immediate American experience but also dares to draw in the outside world.

1. Neil Young: Lets Roll from the album Are You Passionate? Reprise, 2002 and Bruce Springsteen: The Rising. Columbia Records, 2002.

Bibliography

Amis, Martin. The Voice of the Lonely Crowd. The Guardian (June 1, 2002). <http://www.guardian.co.uk/ books/2002/jun/01/philosophy.society>. Beard, Philip. Dear Zoe. New York: Plume, 2005. DeLillo, Don. Falling Man. New York: Scribner, 2007. In the Ruins of the Future. Harpers (December 2001): 33-40. Available from The Guardians website: http:// www.guardian.co.uk/books/2001/dec/22/ction. DeLillo, Don. Mao II. New York: Viking, 1991. Dubus III, Andre. The Garden of Last Days. New York. W. W. Norton & Company, 2008. Foer, Jonathan Safran. Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close. New York: Frost, Laura. Falling Mans Precarious Balance. The American Prospect (May 11, 2007). <http://www.prospect.org/cs/articles?article=falling_mans_precarious_balance>. Hobson, Fred. The Southern Writer in the Postmodern World. Athens: U of Georgia P, 1991. Kalfus, Ken. A Disorder Peculiar to the Country. New York: Ecco, 2006. McInerney, Jay. The Good Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006. Miller, Laura. Falling Man. Salon.com (May 11, 2007). <http://www.salon.com/books/review/2007/05/11/delillo/>. Price, Reynolds. The Good Priests Son. New York: Scribner, 2005. Schepelern, Peter. Terroristerne lavede lm. EKKO 34 (September-October 2006): Schwartz, Lynne Sharon. The Writing on the Wall. New York: Counterpoint, 2005. Updike, John. Terrorist. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006. Walter, Jess. The Zero. New York: Regan, 2006. Wood, James. Black Noise. The New Republic (July 5, 2007). <http://www.powells.com/review/2007_07_05.html>. Tell me how does it feel? The Guardian (October 6, 2001). < http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2001/oct/06/ction>.

When I gave this presentation at Engelsklrerforeningens Generalforsamlingskursus at SDU, several teachers expressed an interest in short stories and poetry about 9/11. The following titles may be of use:

Poetry after 9/11: An Anthology. Ed. Dennis Loy Johnson. New York: Melville House, 2002. September 11, 2001: American Writers Respond. Ed. William Heyen. New York: Etruscan Press, 2002. 110 Stories: New York Writers after September 11. Ed. Ulrich Baer. New York: NYU Press, 2004. Don DeLillo: Looking at Meinhof. The Guardian (August 17, 2002). <http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2002/ aug/17/ction.originalwriting>. Deborah Eisenberg. Twilight of the Superheroes. Twilight of the Superheroes. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2006.

ANGLO FILES | Februar 2009 | 61

You might also like

- John Duvall - Don DeLillo's UnderworldDocument43 pagesJohn Duvall - Don DeLillo's UnderworldRobertoBandaNo ratings yet

- Underworld A Reader's GuideDocument36 pagesUnderworld A Reader's GuideteaguetoddNo ratings yet

- Proposal Version 4 FinalDocument14 pagesProposal Version 4 FinalAlireza AsadiNo ratings yet

- The Contemporary Period (1939 - Present)Document7 pagesThe Contemporary Period (1939 - Present)dulce crissNo ratings yet

- 23 1dohertyDocument21 pages23 1dohertyJeff MburuNo ratings yet

- The Great National DisasterDocument30 pagesThe Great National Disasterlucas parenteNo ratings yet

- In the Shadow of the Towers: Speculative Fiction in a Post-9/11 WorldFrom EverandIn the Shadow of the Towers: Speculative Fiction in a Post-9/11 WorldNo ratings yet

- The Reluctant Fundamentalists Depiction of The PostmodernDocument75 pagesThe Reluctant Fundamentalists Depiction of The PostmodernJaya DasNo ratings yet

- Jewish American Literature - 97Document3 pagesJewish American Literature - 97slnkoNo ratings yet

- Kurt Vonnegut: Brokenhearted American Dreamer: Gregory D. SumnerDocument12 pagesKurt Vonnegut: Brokenhearted American Dreamer: Gregory D. SumnerAurelian Buliga-StefanescuNo ratings yet

- Contextualising 9/11 LiteratureDocument59 pagesContextualising 9/11 LiteratureAlex DuncanNo ratings yet

- Taking Out The Trash: Don Delillo'S Underworld, Liquid Modernity, and The End of GarbageDocument30 pagesTaking Out The Trash: Don Delillo'S Underworld, Liquid Modernity, and The End of GarbageJamie FurnissNo ratings yet

- Ode To The Midwest - Refiguring Lorrie Moores A Gate at The Stairs As A Romantic Response To Post-9-11 Trauma-LibreDocument21 pagesOde To The Midwest - Refiguring Lorrie Moores A Gate at The Stairs As A Romantic Response To Post-9-11 Trauma-LibrelinguistAiaaNo ratings yet

- 20th Century's Greatest Hits: 100 English-Language Books of FictionDocument13 pages20th Century's Greatest Hits: 100 English-Language Books of FictionNaveen AmarasingheNo ratings yet

- Introducing Don Delillo - Frank LentricchiaDocument73 pagesIntroducing Don Delillo - Frank Lentricchiaashishamitav123No ratings yet

- Essential Literary Works Through the CenturiesDocument29 pagesEssential Literary Works Through the CenturiesPretheesh Paul CNo ratings yet

- The Unkillable Dream of The Great American Novel: Moby-Dick As Test CaseDocument34 pagesThe Unkillable Dream of The Great American Novel: Moby-Dick As Test CaseAnas RafiNo ratings yet

- 40.1.miller (PDF Version (153k) )Document2 pages40.1.miller (PDF Version (153k) )giovpNo ratings yet

- Finial Annotated Bibliography For Albert CamasDocument5 pagesFinial Annotated Bibliography For Albert Camasktsanb629No ratings yet

- The Contemporary PeriodDocument15 pagesThe Contemporary Periodloganzx100% (1)

- Don Delillo - Mao II, Underworld, Falling Man PDFDocument207 pagesDon Delillo - Mao II, Underworld, Falling Man PDFsajid ullah khan100% (1)

- Packer, Matthew J - at The Dead Center of Things in Don DeLillo's White Noise - Mimesis, Violence, and Religious AweDocument20 pagesPacker, Matthew J - at The Dead Center of Things in Don DeLillo's White Noise - Mimesis, Violence, and Religious AwePetra PilbákNo ratings yet

- Arthur Miller DissertationDocument7 pagesArthur Miller DissertationDoMyCollegePaperJackson100% (1)

- One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest: The Literary, Historical, and Cultural Contexts ofDocument6 pagesOne Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest: The Literary, Historical, and Cultural Contexts oflolmemNo ratings yet

- Classic British and American Essays and SpeechesDocument9 pagesClassic British and American Essays and SpeechesIndie BotNo ratings yet

- Kurt Vonnegut (From Norton)Document3 pagesKurt Vonnegut (From Norton)Marcin DąbekNo ratings yet

- The Inadvertent Epic. From Uncle Toms Cabin To Roots.Document98 pagesThe Inadvertent Epic. From Uncle Toms Cabin To Roots.José Luis Caballero MartínezNo ratings yet

- Bleeding Edge Neoliberalism and The 911 NovelDocument25 pagesBleeding Edge Neoliberalism and The 911 NovelAnonymous TkpPdPiNo ratings yet

- World of James BondDocument218 pagesWorld of James BondVinay Yadav50% (2)

- Why I Wrote, The CrucibleDocument6 pagesWhy I Wrote, The CrucibleMadison CroweNo ratings yet

- 6comprehension Check On Lecture 6 ELDocument4 pages6comprehension Check On Lecture 6 ELКунжан АбауоваNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of Dystopian Literature and Why 1984 Still PertainsDocument29 pagesThe Evolution of Dystopian Literature and Why 1984 Still PertainsNoor Al hudaNo ratings yet

- Frank TheNovelafter9 11 2019Document21 pagesFrank TheNovelafter9 11 2019luciaNo ratings yet

- POSTMODERN LITERATURE KEY FEATURES (1945Document4 pagesPOSTMODERN LITERATURE KEY FEATURES (1945RinaNo ratings yet

- Miller at the Outpost_The Evolution of Social Warning in An Enemy of the People andDocument15 pagesMiller at the Outpost_The Evolution of Social Warning in An Enemy of the People anddoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Top 10 Postmodernism and Modernism Books: Authors and Works ExplainedDocument7 pagesTop 10 Postmodernism and Modernism Books: Authors and Works ExplainedLyren PalinlinNo ratings yet

- World Trauma Center: Linda S. KauffmanDocument14 pagesWorld Trauma Center: Linda S. KauffmanNajar RimNo ratings yet

- W H Auden September 1 1939 A Literary AnDocument9 pagesW H Auden September 1 1939 A Literary AnabdulNo ratings yet

- Review Bret Easton EllisDocument6 pagesReview Bret Easton EllisRodrigo ZamoranoNo ratings yet

- P2 Orwell, OBrien, SolzhenitsynDocument5 pagesP2 Orwell, OBrien, Solzhenitsynhappyhania23No ratings yet

- 21st Century Lit MastersonDocument10 pages21st Century Lit MastersonHerbie CuffeNo ratings yet

- Steven Moore - The Novel - An Alternative History - Beginnings To 1600 (2013)Document1,205 pagesSteven Moore - The Novel - An Alternative History - Beginnings To 1600 (2013)Fer100% (3)

- Literature Famous AuthorsDocument20 pagesLiterature Famous AuthorsMilagro DíazNo ratings yet

- Aldous Leonard HuxleyDocument9 pagesAldous Leonard HuxleyMelany YcianoNo ratings yet

- المراجعة المركزة الشاملة لمادة المسرحيةDocument50 pagesالمراجعة المركزة الشاملة لمادة المسرحيةtahseen96tNo ratings yet

- The End of the English Novel and the Rise of the British NovelDocument2 pagesThe End of the English Novel and the Rise of the British Novel013AndreeaNo ratings yet

- Vengeance of Rome: The Fourth Volume of the Colonel Pyat QuartetFrom EverandVengeance of Rome: The Fourth Volume of the Colonel Pyat QuartetNo ratings yet

- Truman Capote's Contribution To The Documentary Novel: The Game-Theoretic Dilemmas of in Cold BloodDocument36 pagesTruman Capote's Contribution To The Documentary Novel: The Game-Theoretic Dilemmas of in Cold Blooddwigtrain100% (1)

- Desperate Faith: A Study of Bellow, Salinger, Mailer, Baldwin, and UpdikeFrom EverandDesperate Faith: A Study of Bellow, Salinger, Mailer, Baldwin, and UpdikeNo ratings yet

- Le of A National LiteratureDocument2 pagesLe of A National LiteraturebassemNo ratings yet

- Digital ElectricalsDocument16 pagesDigital ElectricalsjmavjngoeNo ratings yet

- Balay Dako Menu DigitalDocument27 pagesBalay Dako Menu DigitalCarlo -No ratings yet

- 313 Electrical and Electronic Measurements - Types of Electrical Measuring InstrumentsDocument6 pages313 Electrical and Electronic Measurements - Types of Electrical Measuring Instrumentselectrical civilNo ratings yet

- Pilar Fradin ResumeDocument3 pagesPilar Fradin Resumeapi-307965130No ratings yet

- 1st Part PALIAL CasesDocument255 pages1st Part PALIAL CasesAnonymous 4WA9UcnU2XNo ratings yet

- ''Let All God's Angels Worship Him'' - Gordon AllanDocument8 pages''Let All God's Angels Worship Him'' - Gordon AllanRubem_CLNo ratings yet

- Kamala Das Poetry CollectionDocument0 pagesKamala Das Poetry CollectionBasa SwaminathanNo ratings yet

- Outlook Business The Boss July 2015Document14 pagesOutlook Business The Boss July 2015Nibedita MahatoNo ratings yet

- DTF - Houses of The FallenDocument226 pagesDTF - Houses of The FallenShuang Song100% (1)

- Endocrine System Multiple Choice QuestionsDocument42 pagesEndocrine System Multiple Choice QuestionswanderagroNo ratings yet

- String Harmonics in Ravel's Orchestral WorksDocument97 pagesString Harmonics in Ravel's Orchestral WorksYork R83% (6)

- Antenna Tilt GuidelinesDocument24 pagesAntenna Tilt GuidelinesJorge Romeo Gaitan Rivera100% (5)

- MC Data Dig Graphic Organizer 1Document5 pagesMC Data Dig Graphic Organizer 1api-461486414No ratings yet

- JIPMER B.Sc. Prospectus 2016Document31 pagesJIPMER B.Sc. Prospectus 2016Curtis LawsonNo ratings yet

- A480 PDFDocument95 pagesA480 PDFIrma OsmanovićNo ratings yet

- CITY DEED OF USUFRUCTDocument4 pagesCITY DEED OF USUFRUCTeatshitmanuelNo ratings yet

- Competitor Analysis - Taxi Service in IndiaDocument7 pagesCompetitor Analysis - Taxi Service in IndiaSachin s.p50% (2)

- CPS 101 424424Document3 pagesCPS 101 424424Ayesha RafiqNo ratings yet

- Reflective Paper Assignment 2 Professional Practice Level 2Document3 pagesReflective Paper Assignment 2 Professional Practice Level 2api-350779667No ratings yet

- Black EarthDocument12 pagesBlack Earthrkomar333No ratings yet

- Apt 2Document12 pagesApt 2Shashank ShekharNo ratings yet

- VA anesthesia handbook establishes guidelinesDocument11 pagesVA anesthesia handbook establishes guidelinesapierwolaNo ratings yet

- Sap Interface PDFDocument1 pageSap Interface PDFAwais SafdarNo ratings yet

- CHN ReviewerDocument9 pagesCHN ReviewerAnonymousTargetNo ratings yet

- Marketing Communications and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) - Marriage of Convenience or Shotgun WeddingDocument11 pagesMarketing Communications and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) - Marriage of Convenience or Shotgun Weddingmatteoorossi100% (1)

- Garrett-Satan and The Powers (Apocalyptic Vision, Christian Reflection, Baylor University, 2010)Document8 pagesGarrett-Satan and The Powers (Apocalyptic Vision, Christian Reflection, Baylor University, 2010)Luis EchegollenNo ratings yet

- Organizational Behaviour PDFDocument4 pagesOrganizational Behaviour PDFmaria0% (1)

- Con Men ScamsDocument14 pagesCon Men ScamsTee R TaylorNo ratings yet

- DualSPHysics v4.0 GUIDE PDFDocument140 pagesDualSPHysics v4.0 GUIDE PDFFelipe A Maldonado GNo ratings yet

- Research Scholar Progress Report Review FormDocument3 pagesResearch Scholar Progress Report Review FormYepuru ChaithanyaNo ratings yet

- 316 ch1Document36 pages316 ch1katherineNo ratings yet