Professional Documents

Culture Documents

JS19 - BackTsujimura, Natsuko: An Introduction To Japanese Linguisticshaus2

Uploaded by

yrualOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

JS19 - BackTsujimura, Natsuko: An Introduction To Japanese Linguisticshaus2

Uploaded by

yrualCopyright:

Available Formats

Rezensionen

Tsujimura, Natsuko: An Introduction to Japanese Linguistics (Second Edition). Malden et al.: Blackwell Publishing, 2006, 510 pp., $ 49.95

Reviewed by Peter Backhaus*

To start with a clarifying note, An Introduction to Japanese Linguistics is not an introduction to the discipline of linguistics in Japan, but a linguistic introduction to the Japanese language. It is intended to serve as a descriptive source and a theoretical foundation for an audience that includes students and scholars in linguistics as well as those who are interested in the Japanese language more generally (xiii). The book was first published in 1996. The second edition, which is under review here, has been considerably revised and contains several new features. It is over 100 pages longer than the 1996 edition. It consists of an introductory chapter and seven main chapters on phonetics, phonology, morphology*, syntax, semantics*, linguistic variation*, and language acquisition** (* = considerably revised; ** = newly added). Each of the chapters ends with a list of suggested readings and an exercise section. Chapter 2 provides a brief account of the phonetic inventory of Japanese and the basic phonetic terminology used to describe it. Consonants and vowels are discussed in separate sections, each starting with an account of the sounds of the English language. Chapter 3 is about phonology. It discusses the most fundamental phonemic rules in Japanese such as the devoicing of high vowels, assimilation of syllabic /n/, different phonetic realizations of /s/ and /t/, and verbal conjugation rules. It also deals with the problem of sequential voicing (rendaku) and discusses at length the differences between mora and syllable, a topic that will recur on various occasions throughout the book. Other characteristics of the Japanese sound system discussed are accentuation, phonemic rules in forming mimetics, patterns of loan word integration, some properties of casual and fast speech, and constraints on word length. Chapter 4 is an introduction to Japanese morphology. It starts with an account of the basic morphological categories. After a general introduction to morpheme types, Tsujimura discusses issues of word formation.

* This review appeared originally in the LINGUIST List at http:/ /linguistlist. org/issues/18/181030.html.

269

Rezensionen

These include affixation, compounding, reduplication, clipping, and borrowing. In this context, she also introduces the role of the head in word formation patterns (Righthand Head Rule). The second edition comprises additional sections on transitive and intransitive verb pairs, another topic to be taken up several times in the course of the book; nominalization of verbs, adjectives, and whole phrases; and formation rules for noun-verb and verb-verb compounds. Particularly this latter issue is discussed at some length with regard to morphosyntactic problems such as transitivity and argument structure. Despite some unavoidable redundancies, the new sections fit in well with the other parts of the chapter. The subject matter of chapter 5 is syntax. Though in this chapter no noteworthy additions have been made, it remains the core chapter of the book, covering more than 120 pages in total. It starts with introducing some of the key notions in syntactic theory and exemplifies how they map Japanese syntactic structures. The second section briefly discusses transformational rules, mainly focusing on English. Word order and scrambling are examined in the next section, which revolves around differing theories concerning the hierarchical deepness of Japanese syntactic structure. Subsequent sections discuss null anaphora and zero pronouns; characteristics of the Japanese reflexives zibun and zibun-zisin; properties of the Japanese subject and two diagnostic tests to identify it; passives, causatives, and causative passives; relative clauses; unaccusative and unergative verbs; and light verb constructions (verbal noun + -suru). The closing section is intended as a brief update on more recent developments in phrase structure rules, mainly X Theory and its application to Japanese. This section must be understood against the backdrop that, as Tsujimura acknowledges in her introduction to the chapter (206), the analyses provided do not always reflect the most current developments in syntactic theory. However, as a general introduction to the properties of Japanese syntax and its linguistic analysis, the chapter can be considered more than sufficient. Chapter 6 deals with semantics. It has been completely revised and as a result is much more clearly structured than in the 1996 edition. The first section on word and sentence meaning is intended to introduce the reader to some semantic basics including meaning relationships between words (homonymy, polysemy, antonymy), truth conditions, metaphors and idioms, deictic expressions, and mimetics. The next section examines tense and, particularly, aspect. As a matter of fact, it focuses on verbs and verbal morphology, including forms such as -te iru, -te aru and -te simau, and compounds such as -hazimaru/hazimeru and -owaru/oeru, among others. The analysis also casts light on some interesting interfaces with syntax (argument structure) and morphology (verb inflections). The third section ex270

Rezensionen

amines some more syntax-semantics relations of the Japanese verb and in cross-linguistic perspective. Most welcome in this chapter is a newly added section on pragmatics. It starts with Grices cooperative principle and points out how intentional deviation from his four maxims can be construed as meaning beyond the sentence level. Pragmatic characteristics of Japanese that are discussed are the organization of information structure by means of the particles -wa (topic) and -ga (subject), among others, and the predicate morphology desu (formal) vs. da (informal). No direct reference to politeness phenomena is made at this point, probably because the issue is taken up in a separate section in the next chapter. The section ends with presenting some fascinating examples of relative clauses that demonstrate the relevance of contextual information with regard to both meaning construal and grammaticality of an utterance. Chapter 7 is on language variation. It has been reorganized to some extent as well. It starts with a section on regional variation that reminds the reader that Japanese comprises much more than the so-called standard language spoken in the greater Tokyo area. The residuary two sections deal with sociolinguistic problems: Styles and Levels of Speech is an extended version of the section called Honorifics in the first edition. Particularly important are some new paragraphs commenting on the considerable gap between ideological norms about honorifics and their real usage. The concluding section on gender differences makes a similar point. After discussing the most frequently quoted gender markers (personal pronouns, sentence-final particles, beautification, etc.) Tsujimura refers to some recent empirical research suggesting that many of the classical gender differences in Japanese do not hold water when the linguistic practices of real people are considered. The newly added Chapter 8 deals with language acquisition phenomena, i.e., how children learn to speak Japanese. The first section works out various regularities in Japanese childrens language with regard to moraic structure, the lexicalization of mimetics, and the marking of tense and aspect. This theme is followed up in the next section, which is on speech errors resulting from overgeneralizations. Issues discussed include inflectional morphology in negation, case particles (indiscriminate use of -ga to mark the first NP in a sentence), and prenominal modification (over- and undergeneralization of -no). Theoretical approaches to verb acquisition are dealt with in the next section, which juxtaposes the syntactic and the semantic bootstrapping hypotheses and discusses problems of each of the two when applied to Japanese. The closing section is on acquisition phenomena in the realm of pragmatics that attest to childrens amazingly high awareness of issues such as honorifics and gender distinctions from an early age on. Since this new chapter deals with issues from each of the 271

Rezensionen

linguistic levels discussed in the previous chapters, its attachment at the end of the book has been a wise decision. An Introduction to Japanese Linguistics is an extensive and well-organized linguistic account of the Japanese language that will serve as an extremely helpful source of reference to everyone interested in Japanese and its linguistic analysis. Among the many creditable points of the book is that the discussion frequently centers around some linguistic problem (e.g., mora vs. syllable, rendaku patterns, transitive vs. intransitive verbs) that re-occurs in the later parts of the book. This way of organization is very stimulating in that it invites the reader to look beyond one single linguistic level of analysis in order to understand a linguistic phenomenon. Another strength of the book is its well-balanced use of English examples and its general focus on common points rather than differences between the two languages. With special regard to the second edition, I have already mentioned that the revisions, particularly in the chapters on semantics and on linguistic variation, clearly enhance the quality of the book as a whole. The same holds true for the new chapter on language acquisition. Further noteworthy in this respect is that the exercise sections and the lists of suggested readings have been updated and adapted to the new contents. The new edition thus is clearly more than a mere reprint of the 1996 version. On a general note, some readers may be surprised by the striking differences in coverage of the linguistic subfields. Thus, syntactic problems are discussed on over 120 pages, whereas the language variation chapter covers only 20 pages, ten less even than in the first edition. However, since Tsujimura explicitly mentions this discrepancy in her new Preface (xiii), we may be looking forward to the books third edition. In this context, it should also be mentioned that a brief introduction to the Japanese writing system would be highly welcome. Though the primary goal of the book is to examine spoken Japanese (xiii), many readers would certainly profit from some background information on its graphic representation as well. Moreover, this would considerably add to the general understanding of phenomena such as the moraic structure of Japanese, rendaku rules, or the integration of English loan words. The discussion of these issues at times appears unnecessarily complicated owing to missing references to the Japanese writing system. In the same vein, it would be desirable to include a brief paragraph stating more explicitly that the Kunrei rather than the Hepburn transliteration system is used (mentioned only once on p. 5 in brackets), but that Japanese loan words in English are usually based on Hepburn rules. This would prevent confusing readers not too experienced with Japanese, who may be puzzled by the co-occurrence of terms like susi and sushi throughout the 272

Rezensionen

book. One last suggestion for future editions of the book is a brief bilingual glossary of technical terms, which would no doubt be highly appreciated by both Japanese and English readers. All in all, the second edition of An Introduction to Japanese Linguistics is not only a stimulating and well-structured textbook, but an essential source of reference to everyone interested in the linguistic analysis of Japanese.

273

You might also like

- 50 Japanese Short Stories for Beginners: Read Entertaining Japanese Stories to Improve your Vocabulary and Learn Japanese While Having FunFrom Everand50 Japanese Short Stories for Beginners: Read Entertaining Japanese Stories to Improve your Vocabulary and Learn Japanese While Having FunRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (4)

- Who Are We? (Japanese-English): Language Lizard Bilingual Living in Harmony SeriesFrom EverandWho Are We? (Japanese-English): Language Lizard Bilingual Living in Harmony SeriesNo ratings yet

- The Study of Politeness and Womens Langu PDFDocument16 pagesThe Study of Politeness and Womens Langu PDFSelena RajovicNo ratings yet

- Japanese Spoken Language Faculty GuideDocument112 pagesJapanese Spoken Language Faculty Guidenomuse100% (1)

- PDFDocument268 pagesPDFZeina100% (1)

- Japanese Language TeachingDocument225 pagesJapanese Language TeachingjorgemarcellosNo ratings yet

- The Passive in JapaneseDocument268 pagesThe Passive in JapaneseIkarotNo ratings yet

- Effects of Native-Language and Sex On Back-Channel Behavior - FekeDocument12 pagesEffects of Native-Language and Sex On Back-Channel Behavior - Fekeandré_kunzNo ratings yet

- Mouton Japanese Dialects Proposal FinalDocument16 pagesMouton Japanese Dialects Proposal FinalalexandreqNo ratings yet

- Japanese Culture As Reflected Through The Japanese LanguageDocument9 pagesJapanese Culture As Reflected Through The Japanese LanguagescaredzoneNo ratings yet

- Japanese Grammar PatternsDocument50 pagesJapanese Grammar PatternsVeronica Hampton0% (1)

- Handbook of Japanese Phonetics and PhonologyDocument1,219 pagesHandbook of Japanese Phonetics and Phonology최담종No ratings yet

- Japanese SociolinguisticsDocument19 pagesJapanese SociolinguisticsZeinaNo ratings yet

- Kitamura With Cover Page v2Document9 pagesKitamura With Cover Page v2Titus ArdityoNo ratings yet

- Butler & Iino (2005) Current Japanese Reforms in English Language Education-The 2003 Action PlanDocument21 pagesButler & Iino (2005) Current Japanese Reforms in English Language Education-The 2003 Action PlanJoel Rian100% (1)

- A OF Advanced Grammar: Dictionary JabvneseDocument845 pagesA OF Advanced Grammar: Dictionary JabvneseLunar EclipseNo ratings yet

- JapaneseAccent PDFDocument4 pagesJapaneseAccent PDFMuhammadDwiNo ratings yet

- JLPT Practice - Particles 助詞Document2 pagesJLPT Practice - Particles 助詞ryuuki09No ratings yet

- Basic Nihongo 1 Lesson 1Document35 pagesBasic Nihongo 1 Lesson 1Irish Nicole RouraNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Rituals For Thanking in Japanese: Balancing ObligationsDocument25 pagesLinguistic Rituals For Thanking in Japanese: Balancing ObligationsNur AiniNo ratings yet

- Old JapaneseDocument13 pagesOld Japanese田中将大0% (1)

- Course Instructions Poster PDFDocument2 pagesCourse Instructions Poster PDFAnonymous ThNeatVlNo ratings yet

- 9027259216japanese PDFDocument320 pages9027259216japanese PDFDaly Balty100% (2)

- The Concept of Subjectivity in LanguageDocument24 pagesThe Concept of Subjectivity in LanguageSheila EtxeberriaNo ratings yet

- ashita wa 明 日 はDocument5 pagesashita wa 明 日 はbakaeliteNo ratings yet

- Japanese Teachers GuideDocument224 pagesJapanese Teachers GuideSakuraPhạm100% (3)

- Japanese Women's Speech - Changing Language, Changing RolesDocument18 pagesJapanese Women's Speech - Changing Language, Changing RolesJournal of Undergraduate Research67% (3)

- An Introduction To JapaneseDocument181 pagesAn Introduction To JapanesecoltNo ratings yet

- Japanese Verb Conjugation Presentation For Learning Another LanguageDocument22 pagesJapanese Verb Conjugation Presentation For Learning Another LanguagejennaiiiNo ratings yet

- Ku Japanese and Japan Studies 2011Document64 pagesKu Japanese and Japan Studies 2011Sanjyot KolekarNo ratings yet

- Dokumen - Tips - Shin Bunka Shoukyuu Nihongo I Renshuu Mondaishuu PDFDocument106 pagesDokumen - Tips - Shin Bunka Shoukyuu Nihongo I Renshuu Mondaishuu PDFVegha PangestuNo ratings yet

- History of Japanese Literature Based On BooksDocument1 pageHistory of Japanese Literature Based On BooksMody BickNo ratings yet

- How To Use Our Text Books. Minna No NihongoDocument4 pagesHow To Use Our Text Books. Minna No NihongoCezar Negru100% (1)

- Japanese Respect Language 4805309768Document92 pagesJapanese Respect Language 4805309768dywrulez100% (2)

- A Differentiated/Integrated Approach To: Shadowing and RepeatingDocument12 pagesA Differentiated/Integrated Approach To: Shadowing and RepeatingAhmadNo ratings yet

- Minna No Nihongo I ContieneDocument1 pageMinna No Nihongo I Contieneadrianjiraiya100% (1)

- Tanki Master JLPT N4 With CDDocument1 pageTanki Master JLPT N4 With CDKato MotatoNo ratings yet

- Basic Japanese ExpressioonsDocument15 pagesBasic Japanese ExpressioonsRicardo RibeiroNo ratings yet

- JLPT Guide - JLPT N4 Grammar - Wikibooks, Open Books For An Open WorldDocument45 pagesJLPT Guide - JLPT N4 Grammar - Wikibooks, Open Books For An Open WorldShi No GekaiNo ratings yet

- Japanese Basic GrammarDocument36 pagesJapanese Basic GrammaritsumoAoi100% (7)

- Obento Senior Grammar BookletDocument105 pagesObento Senior Grammar Bookletthali13No ratings yet

- In Flight JapaneseDocument20 pagesIn Flight Japanesecaroline_life100% (3)

- Instant Japanese - How To Express 1,000 Different IdeasDocument49 pagesInstant Japanese - How To Express 1,000 Different Ideaskim100% (1)

- Japanese Culture and TraditionDocument13 pagesJapanese Culture and TraditionGaming Boy 12No ratings yet

- AIJ1 4th Edition Textbook SampleDocument55 pagesAIJ1 4th Edition Textbook Sampleaddalma100% (1)

- けいようし Keiyoshi: AdjectivesDocument12 pagesけいようし Keiyoshi: AdjectivesWayneNo ratings yet

- Writing Technology in Meiji Japan: Harvard East Asian Monographs 387Document320 pagesWriting Technology in Meiji Japan: Harvard East Asian Monographs 387Marco VinhasNo ratings yet

- Learn Japanese Cheat SheetDocument6 pagesLearn Japanese Cheat SheetnioraiNo ratings yet

- Anime PhrasesDocument2 pagesAnime Phraseswillian01No ratings yet

- Features of This Book: Intercultural UnderstandingDocument3 pagesFeatures of This Book: Intercultural Understandingdvdantunes0% (1)

- The 214 Traditional Kanji Radicals and Their VariantsDocument18 pagesThe 214 Traditional Kanji Radicals and Their VariantsAdryanz Dias100% (1)

- The Linguistics System and Sounds of JapaneseDocument258 pagesThe Linguistics System and Sounds of Japanesemaqsood hasni100% (1)

- A1 RikaiDocument2 pagesA1 RikaiChaitra Patil100% (1)

- The Wheels The Friendship Race タイヤ友情のレース: English Japanese Bilingual CollectionFrom EverandThe Wheels The Friendship Race タイヤ友情のレース: English Japanese Bilingual CollectionNo ratings yet

- My Mom is Awesome (Japanese Bilingual book): English Japanese Bilingual CollectionFrom EverandMy Mom is Awesome (Japanese Bilingual book): English Japanese Bilingual CollectionNo ratings yet

- English Loanwords in Japanese: A Selection: Learn Japanese Vocabulary the Easy Way with this Useful Japanese Phrasebook, Dictionary & Grammar GuideFrom EverandEnglish Loanwords in Japanese: A Selection: Learn Japanese Vocabulary the Easy Way with this Useful Japanese Phrasebook, Dictionary & Grammar GuideRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- ぼくは、あきがだいすきだ I Love Autumn: Japanese English Bilingual CollectionFrom Everandぼくは、あきがだいすきだ I Love Autumn: Japanese English Bilingual CollectionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Second Language Acquisition and Learning - KrashenDocument154 pagesSecond Language Acquisition and Learning - KrashenlordybyronNo ratings yet

- Language LearningDocument13 pagesLanguage LearningyrualNo ratings yet

- Language LearningDocument13 pagesLanguage LearningyrualNo ratings yet

- SCP EngDocument2 pagesSCP EngyrualNo ratings yet

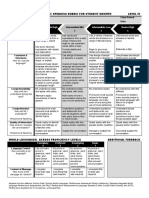

- Speaking Rubric Level IVDocument1 pageSpeaking Rubric Level IVapi-238564123No ratings yet

- Starter A Starter B Starter C Starter: ReadingDocument1 pageStarter A Starter B Starter C Starter: ReadingloliNo ratings yet

- iTOLC Felkészítő Könyv - Angol B2 I. Rész (Letölthető Könyv)Document67 pagesiTOLC Felkészítő Könyv - Angol B2 I. Rész (Letölthető Könyv)Juszuf100% (4)

- Sentence FragmentDocument30 pagesSentence FragmentJoshua Robert Catabay BaldovinoNo ratings yet

- Classroom Activities: Contributor Materials Brief Description of ActivityDocument9 pagesClassroom Activities: Contributor Materials Brief Description of ActivityJefferson VilelaNo ratings yet

- BK Acx0 152509Document184 pagesBK Acx0 152509AngelNo ratings yet

- (Linguistic Inquiry Monographs) Alec Marantz-On The Nature of Grammatical Relations (Linguistic Inquiry Monographs, 10) - The MIT Press (1984)Document355 pages(Linguistic Inquiry Monographs) Alec Marantz-On The Nature of Grammatical Relations (Linguistic Inquiry Monographs, 10) - The MIT Press (1984)Janayna CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Grade 9 English CompleteDocument22 pagesGrade 9 English CompleteRomeo Acero-AbuhanNo ratings yet

- Great Sentences Teacher's NotesDocument55 pagesGreat Sentences Teacher's Notescommweng0% (1)

- A Continuous Journey 1Document3 pagesA Continuous Journey 1Juan RamirezNo ratings yet

- Phases - Level 3 - 2nd Edition - Teacher S Book - Unit 2Document12 pagesPhases - Level 3 - 2nd Edition - Teacher S Book - Unit 2Rodolfo MoyanoNo ratings yet

- Adjective Clauses in Complex SentencesDocument5 pagesAdjective Clauses in Complex Sentencesbondan iskandarNo ratings yet

- PoemsDocument14 pagesPoemsTom WildNo ratings yet

- Verbal Ability Work Book-2 PDFDocument28 pagesVerbal Ability Work Book-2 PDFMughal AsifNo ratings yet

- Idioms and Phrases Marathon 1 Nov PDF 1636913210115Document200 pagesIdioms and Phrases Marathon 1 Nov PDF 1636913210115md.muzzammil shaikhNo ratings yet

- Definition SyntaxDocument7 pagesDefinition SyntaxRudi IrawanNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH 7 - Q1 - Mod5Document27 pagesENGLISH 7 - Q1 - Mod5Ariane del Rosario100% (1)

- University Goce Delcev Stip Faculty of Philology: Department of English Language and LiteratureDocument41 pagesUniversity Goce Delcev Stip Faculty of Philology: Department of English Language and LiteratureDanica DragoljevikNo ratings yet

- Materi Ajar Bahasa Inggris 1 & 2Document74 pagesMateri Ajar Bahasa Inggris 1 & 2Linda AsmaraNo ratings yet

- Syntax Page 21,22,32Document2 pagesSyntax Page 21,22,32Nada Aulia88% (8)

- Deno and Conno NotesDocument6 pagesDeno and Conno NotesANGELA MAMARILNo ratings yet

- Positioning P He in Four Discourse QuadrantsDocument21 pagesPositioning P He in Four Discourse QuadrantsFrances Ian Clima100% (1)

- Inversion and FrontingDocument7 pagesInversion and FrontingCielo LafuenteNo ratings yet

- CAT Grammar and Word Usage by Bodhee Prep-150 PagesDocument150 pagesCAT Grammar and Word Usage by Bodhee Prep-150 PagesskharoonNo ratings yet

- Commo Mistakes and Speaking Success SystemDocument11 pagesCommo Mistakes and Speaking Success SystemDuyên LêNo ratings yet

- Functions of Phrases FinalDocument27 pagesFunctions of Phrases Finalhasna hasnaNo ratings yet

- Zentella - The Grammar of SpanglishDocument22 pagesZentella - The Grammar of SpanglishLuis RomanoNo ratings yet

- Sylvester and The Magic Pebble S2Document25 pagesSylvester and The Magic Pebble S2S TANCRED100% (1)

- Lan 105 First QuarterDocument8 pagesLan 105 First QuarterDea SantellaNo ratings yet

- The Feminine StyleDocument6 pagesThe Feminine Styleamiller1987No ratings yet