Professional Documents

Culture Documents

To Read or Not To Read: National Endowment Arts

Uploaded by

shush100 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

38 views20 pagesThis document summarizes the key findings of the report "To Read or Not To Read" published by the National Endowment for the Arts. The report finds that Americans, especially teenagers and young adults, are reading less and have weaker reading comprehension skills. These declines are correlated with lower academic achievement, less success in the job market, and less civic participation. While the data does not prove causation, it suggests reading plays an important role in positive individual and social outcomes. The report calls for increased efforts to address this problem, as continued declines in reading could have serious economic and social consequences for the nation.

Original Description:

Research on reading

Original Title

ToRead ExecSum

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document summarizes the key findings of the report "To Read or Not To Read" published by the National Endowment for the Arts. The report finds that Americans, especially teenagers and young adults, are reading less and have weaker reading comprehension skills. These declines are correlated with lower academic achievement, less success in the job market, and less civic participation. While the data does not prove causation, it suggests reading plays an important role in positive individual and social outcomes. The report calls for increased efforts to address this problem, as continued declines in reading could have serious economic and social consequences for the nation.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

38 views20 pagesTo Read or Not To Read: National Endowment Arts

Uploaded by

shush10This document summarizes the key findings of the report "To Read or Not To Read" published by the National Endowment for the Arts. The report finds that Americans, especially teenagers and young adults, are reading less and have weaker reading comprehension skills. These declines are correlated with lower academic achievement, less success in the job market, and less civic participation. While the data does not prove causation, it suggests reading plays an important role in positive individual and social outcomes. The report calls for increased efforts to address this problem, as continued declines in reading could have serious economic and social consequences for the nation.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 20

National Endowment for the Arts

To Read or Not To Read

A Question of National Consequence

Executive Summary

Reseaich Repoit #47

Executive Summaiy

Novembei 2007

National Endowment for the Arts

1100 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW

Washington, DC 20506-0001

Telephone: 202-682-5400

Pioduced by the Oce of Reseaich & Analysis

Sunil Iyengai, Diiectoi

Sta contiibutois: Saiah Sullivan, Bonnie Nichols, Tom Biadshaw,

and Kelli Rogowski

Special contiibutoi: Maik Baueilein

Editoiial and publication assistance by Don Ball

Designed by Beth Schleno Design

Fiont Covei Photo: Getty Images

Piinted in the United States of Ameiica

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

To iead oi not to iead : a question of national consequence.

p. cm. (Reseaich iepoit , #47)

Pioduced by the Oce of Reseaich & Analysis, National

Endowment foi the Aits, Sunil Iyengai, diiectoi, editoiial and

publication assistance by Don Ball.

1. Books and ieadingUnited States. 2.

LiteiatuieAppieciationUnited States. I. Iyengai, Sunil, 1973

II. Ball, Don, 1964 III. National Endowment foi the Aits.

Z1003.2.T6 2007

028.9dc22

2007042469

202-682-5496 Voice/TTY

(a device foi individuals who aie deaf oi heaiing-impaiied)

Individuals who do not use conventional piint mateiials

may contact the Aits Endowments Oce foi AccessAbility at

202-682-5532 to obtain this publication in an alteinate foimat.

is publication is available free of charge at www.arts.gov,

the Web site of the National Endowment for the Arts.

Pvrrcr

T

o Read or Not To Read gatheis and collates the best national data available to

piovide a ieliable and compiehensive oveiview of Ameiican ieading today.

While it incoipoiates some statistics fiom the National Endowment foi the

Aits 2004 iepoit, Reading at Risk, this new study contains vastly moie data fiom

numeious souices. Although most of this infoimation is publicly available, it has

nevei been assembled and analyzed as a whole. To oui knowledge, To Read or Not

To Read is the most complete and up-to-date iepoit of the nations ieading tiends

andpeihaps most impoitanttheii consideiable consequences.

To Read or Not To Read ielies on the most accuiate data available, which consists

of laige, national studies conducted on a iegulai basis by U.S. fedeial agencies, sup-

plemented by academic, foundation, and business suiveys. Reliable national statisti-

cal ieseaich is expensive and time-consuming to conduct, especially when it iequiies

accuiate measuiements of vaiious subgioups (age oi education level, foi example)

within the oveiall population. Likewise, such ieseaich demands foimidable iesouices

and a commitment fiom an oiganization to collect the data consistently ovei many

yeais, which is the only valid way to measuie both shoit and long-teim tiends. Few

oiganizations outside the fedeial goveinment can manage such a painstaking task.

By compaiison, most piivate-sectoi oi media suiveys involve quick and isolated polls

conducted with a minimal sample size.

When one assembles data fiom dispaiate souices, the iesults often piesent con-

tiadictions. Tis is not the case with To Read or Not To Read. Heie the iesults aie

staitling in theii consistency. All of the data combine to tell the same stoiy about

Ameiican ieading.

Te stoiy the data tell is simple, consistent, and alaiming. Although theie has been

measuiable piogiess in iecent yeais in ieading ability at the elementaiy school level,

all piogiess appeais to halt as childien entei theii teenage yeais. Teie is a geneial

decline in ieading among teenage and adult Ameiicans. Most alaiming, both ieading

ability and the habit of iegulai ieading have gieatly declined among college giaduates.

Tese negative tiends have moie than liteiaiy impoitance. As this iepoit makes cleai,

the declines have demonstiable social, economic, cultuial, and civic implications.

Howdoes one summaiize this distuibing stoiy? As Ameiicans, especially youngei

Ameiicans, iead less, they iead less well. Because they iead less well, they have lowei

levels of academic achievement. (Te shameful fact that neaily one-thiid of Ameii-

can teenageis diop out of school is deeply connected to declining liteiacy and ieading

compiehension.) With lowei levels of ieading and wiiting ability, people do less well

in the job maiket. Pooi ieading skills coiielate heavily with lack of employment,

lowei wages, and fewei oppoitunities foi advancement. Signicantly woise ieading

skills aie found among piisoneis than in the geneial adult population. And decient

ieadeis aie less likely to become active in civic and cultuial life, most notably in vol-

unteeiism and voting.

Stiictly undeistood, the data in this iepoit do not necessaiily show cause and

eect. Te statistics meiely indicate coiielations. Te habit of daily ieading, foi

instance, oveiwhelmingly coiielates with bettei ieading skills and highei academic

To Read or Not To Read 3

Photo by Vance Jacobs

achievement. On the othei hand, pooi ieading skills coiielate with lowei levels of

nancial and job success. At the iisk of being ciiticized by social scientists, I suggest

that since all the data demonstiate consistent and mostly lineai ielationships between

ieading and these positive iesultsand between pooi ieading and negative iesults

ieading has played a decisive factoi. Whethei oi not people iead, and indeed how

much and how often they iead, aects theii lives in ciucial ways.

All of the data suggest how poweifully ieading tiansfoims the lives of individu-

alswhatevei theii social ciicumstances. Regulai ieading not only boosts the likeli-

hood of an individuals academic and economic successfacts that aie not especially

suipiisingbut it also seems to awaken a peisons social and civic sense. Reading

coiielates with almost eveiy measuiement of positive peisonal and social behavioi

suiveyed. It is ieassuiing, though haidly amazing, that ieadeis attend moie conceits

and theatei than non-ieadeis, but it is suipiising that they exeicise moie and play

moie spoitsno mattei what theii educational level. Te cold statistics conim

something that most ieadeis knowbut have mostly been ieluctant to declaie as fact

books change lives foi the bettei.

Some people will inevitably ciiticize To Read or Not To Read as a negative iepoit

undeistating the good woiks of schools, colleges, libiaiies, and publisheis. Ceitainly,

the tiends iepoited heie aie negative. Teie is, alas, no factual case to suppoit geneial

giowth in ieading oi ieading compiehension in Ameiica. But theie is anothei way

of viewing this data that is haidly negative about ieading.

To Read or Not To Read conimswithout any seiious qualicationthe cential

impoitance of ieading foi a piospeious, fiee society. Te data heie demonstiate that

ieading is an iiieplaceable activity in developing pioductive and active adults as well

as healthy communities. Whatevei the benets of newei electionic media, they pio-

vide no measuiable substitute foi the intellectual and peisonal development initiated

and sustained by fiequent ieading.

To Read or Not To Read is not an elegy foi the bygone days of piint cultuie, but

instead is a call to actionnot only foi paients, teacheis, libiaiians, wiiteis, and pub-

lisheis, but also foi politicians, business leadeis, economists, and social activists. Te

geneial decline in ieading is not meiely a cultuial issue, though it has enoimous con-

sequences foi liteiatuie and the othei aits. It is a seiious national pioblem. If, at the

cuiient pace, Ameiica continues to lose the habit of iegulai ieading, the nation will

suei substantial economic, social, and civic setbacks.

As with Reading at Risk, we issue this iepoit not to dictate any specic iemedial

policies, but to initiate a seiious discussion. It is no longei ieasonable to debate

whethei the pioblem exists. It is now time to become moie committed to solving it

oi face the consequences. Te nation needs to focus moie attention and iesouices

on an activity both fundamental and iiieplaceable foi demociacy.

Dana Gioia

Chairman, National Endowment for the Arts

4 To Read or Not To Read

Exrcu:ivr Surrvv

I

n 2004, the National Endowment foi the Aits published Reading at Risk: ASurvey

of Literary Reading in America. Tis detailed study showed that Ameiicans in

almost eveiy demogiaphic gioup weie ieading ction, poetiy, and diamaand

books in geneialat signicantly lowei iates than 10 oi 20 yeais eailiei. Te declines

weie steepest among young adults.

Moie iecent ndings attest to the diminished iole of voluntaiy ieading in Ameii-

can life. Tese newstatistics come fioma vaiiety of ieliable souices, including laige,

nationally iepiesentative studies conducted by othei fedeial agencies. Biought

togethei heie foi the ist time, the data piompt thiee unsettling conclusions:

Americans are spending less time reading.

Reading comprehension skills are eroding.

These declines have serious civic, social, cultural, andeconomic implications.

A. Arrvics Avr Rroio Lrss

Teens and young adults iead less often and foi shoitei amounts of time when com-

paied with othei age gioups and with Ameiicans of the past.

1. Young adults are reading fewer books in general.

Neaily half of all Ameiicans ages 18 to 24 iead no books foi pleasuie.

Te peicentage of 18- to 44-yeai-olds who iead a book fell 7 points fiom 1992

to 2002.

2. Reading is declining as an activity among teenagers.

Less than one-thiid of 13-yeai-olds aie daily ieadeis.

Te peicentage of 17-yeai-olds who iead nothing at all foi pleasuie has

doubled ovei a 20-yeai peiiod. Yet the amount they iead foi school oi home-

woik (15 oi fewei pages daily foi 62 of students) has stayed the same.

To Read or Not To Read 5

Percentage of Young Americans Who Read a Book Not Required for Work or School

Age group 1992 2002 Change Rate of decline

1824 59% 52% -7 pp -12%

2534 64% 59% -5 pp -8%

3544 66% 59% -7 pp -11%

All adults (18 and over) 61% 57% -4 pp -7%

pp = percentage points

Source: National Endowment for the Arts

Voluntaiy ieading iates diminish fiom childhood to late adolescence.

3. College attendance no longer guarantees active reading habits.

Although ieading tiacks closely with education level, the peicentage of college

giaduates who iead liteiatuie has declined.

65 of college fieshmen iead foi pleasuie foi less than an houi pei week oi not

at all.

Te peicentage of non-ieadeis among these students has neaily doubled

climbing 18 points since they giaduated fiom high school.

6 To Read or Not To Read

Percentage of Students Reading for Fun

Age 13 Age 17

Reading frequency 1984 2004 Change 1984 2004 Change

Never or hardly ever read 8% 13% +5 pp 9% 19% +10 pp

Read almost every day 35% 30% -5 pp 31% 22% -9 pp

pp = percentage points

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics

Percentage Who Read Almost Every Day for Fun

1984 1999 2004

9-year-olds 53% 54% 54%

13-year-olds 35% 28% 30%

17-year-olds 31% 25% 22%

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics

Percentage Who Read a Book the Previous Day (Outside School or Work)

In 2004

For at least 5 minutes For at least 30 minutes

8- to 10-year-olds 63% 40%

11- to 14-year-olds 44% 27%

15- to 18-year-olds 34% 26%

Source: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Generation M: Media in the Lives of 8-18 Year-Olds (#7251), 2005

Percentage of Literary Readers Among College Graduates

Change Rate of decline

1982 1992 2002 19822002 19822002

82% 75% 67% -15 pp -18%

pp = percentage points

Source: National Endowment for the Arts

By the time they become college seniois, one in thiee students iead nothing at

all foi pleasuie in a given week.

4. Teens andyoung adults spendless time reading thanpeople of other age groups.

Ameiicans between 15 and 34 yeais of age devote less leisuie time than oldei

age gioups to ieading anything at all.

15- to 24-yeai-olds spend only 710 minutes pei day on voluntaiy ieading

about 60 less time than the aveiage Ameiican.

To Read or Not To Read 7

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

21%

39%

26% 26%

T

o

t

a

l

None

Less than 1 hour

As high school seniors

in 2004

As college freshmen

in 2005

Reading per week:

Percentage of U.S. College Freshmen Who Read Little or Nothing for Pleasure

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

21%

35%

28% 28%

T

o

t

a

l

None

Less than 1 hour

As high school seniors

(mainly pre-2002)

As college seniors

in 2005

Reading per week:

Percentage of U.S. College Seniors Who Read Little or Nothing for Pleasure

Source: University of California, Los Angeles, Higher Education Research Institute

Source: University of California, Los Angeles, Higher Education Research Institute

i

U.S. Census Buieau, Computer

and Internet Use in the United

States, 1997 and 2003, and

PewiInteinet & Ameiican Life

Pioject, Home Broadband

Adoption 2007.

By contiast, 15- to 24-yeai-olds spend 2 to 2 houis pei day watching TV. Tis

activity consumes the most leisuie time foi men and women of all ages.

Liteiaiy ieading declined signicantly in a peiiod of iising Inteinet use. Fiom

19972003, home Inteinet use soaied 53 peicentage points among 18- to 24-

yeai-olds. By anothei estimate, the peicentage of 18- to 29-yeai-olds with a

home bioadband connection climbed 25 points fiom 2005 to 2007.

i

5. Even when reading does occur, it competes with other media. is multi-

tasking suggests less focused engagement with a text.

58 of middle and high school students use othei media while ieading.

Students iepoit using media duiing 35 of theii weekly ieading time.

20 of theii ieading time is shaied by TV-watching, videoicomputei game-

playing, instant messaging, e-mailing oi Web suing.

8 To Read or Not To Read

Percentage Using Other Media While Reading

7th-12th Graders in 20032004

% who use other media while reading

Most of the time 28%

Some of the time 30%

Most/some 58%

Little of the time 26%

Never 16%

Little/never 42%

Source: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Media Multitasking Among Youth: Prevalence, Predictors

and Pairings (# 7592), 2006

Average Time Spent Reading in 2006

Hours/minutes spent reading

Weekdays Weekends

and holidays

Total, 15 years and over :20 :26

15 to 24 years :07 :10

25 to 34 years :09 :11

35 to 44 years :12 :16

45 to 54 years :17 :24

55 to 64 years :30 :39

65 years and over :50 1:07

Source: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics

Percentage of 18- to 24-Year-Olds Reading Literature

1982 1992 2002

Percentage reading literature 60% 53% 43%

Change from 1982 # -7 pp -17 pp

Rate of decline from 1982 # -12% -28%

pp = percentage points

Source: National Endowment for the Arts

ii

Foi the puipose of this analysis,

family oi household is used

instead of the Buieau of Laboi

Statistics technical teim con-

sumei unit. In addition to families

and households, a consumei unit

may desciibe a peison living

alone oi shaiing a household with

otheis oi living as a ioomei in a

piivate home oi lodging house oi

in peimanent living quaiteis in a

hotel oi motel, but who is nan-

cially independent.

iii

Albeit N. Gieco and Robeit M.

Whaiton, Book Industry TRENDS

2007 (New Yoik, N.Y.: Book

Industiy Study Gioup, 2007),

vaiious pages.

6. American families are spending less on books than at almost any other time

in the past two decades.

Although nominal spending on books giew fiom 1985 to 2005, aveiage annual

household spending on books diopped 14 when adjusted foi ination.

ii

Ovei the same peiiod, spending on ieading mateiials dipped 7 peicentage

points as a shaie of aveiage household enteitainment spending.

Amid yeai-to-yeai uctuations, consumei book sales peaked at 1.6 billion

units sold in 2000. Fiom 2000 to 2006, howevei, they declined by 6, oi

100 million units.

iii

Te numbei of books in a home is a signicant piedictoi of academic

achievement.

To Read or Not To Read 9

$26

$28

$30

$32

$34

$36

1985 1989 1993 1997 2001 2005

Average Annual Spending on Books, by Consumer Unit

Adjusted for Inflation

The Consumer Price Index, 19821984 (less food and energy), was used to adjust for inflation.

Source: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics

Percentage of Time Spent Reading While Using Other Media

7th- to 12th-Graders in 20032004

Percentage of reading time

Reading while:

Watching TV 11%

Listening to music 10%

Doing homework on the computer 3%

Playing videogames 3%

Playing computer games 2%

Using the computer (other) 2%

Instant messaging 2%

E-mailing 1%

Surfing websites 1%

Using any of the above media 35%

Source: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Media Multitasking Among Youth: Prevalence, Predictors

and Pairings (# 7592), 2006

B. Arrvics Avr Rroio Lrss Wrii

As Ameiicans iead less, theii ieading skills woisen, especially among teenageis and

young males. By contiast, the aveiage ieading scoie of 9-yeai-olds has impioved.

1. Reading scores for 17-year-olds are down.

17-yeai-old aveiage ieading scoies began a slow downwaid tiend in 1992.

Foi moie than 30 yeais, this age gioup has failed to sustain impiovements in

ieading scoies.

Reading test scoies foi 9-yeai-oldswho show no declines in voluntaiy

ieadingaie at an all-time high.

Te dispaiity in ieading skills impiovement between 9-yeai-olds and 17-yeai-

olds may ieect bioadei dieiences in the academic and social climate of

those age gioups.

10 To Read or Not To Read

Average Test Scores by Number of Household Books, Grade 12 (20052006)

Average Average Average

science score civics score history score*

Reported number of

books at home

More than 100 161 167 305

26100 147 150 289

1125 132 134 275

010 122 123 265

* Science and civics scores range from 0 to 300. History scores range from 0 to 500.

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics

10

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

8

1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1999 2004

Reported as differences from 1984 reading scores.

Age 17

Age 9

Trend in Average Reading Scores for Students Ages 17 and 9

Test years occurred at irregular intervals.

Trend analysis based on data from the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

iv

Foi 12th-giadeis, Piocient

coiiesponds with a ieading scoie

of 302 oi gieatei (out of 500).

2. Among high school seniors, the average score has declined for virtually all

levels of reading.

Little moie than one-thiid of high school seniois now iead piociently.

iv

Fiom 1992 to 2005, the aveiage scoie declined foi the bottom 90 of ieadeis.

Only foi the veiy best ieadeis of 2005, the scoie held steady.

Te ieading gap is widening between males and females.

To Read or Not To Read 11

Average 12th-Grade Reading Scores by Gender

1992 2005

Female 297 292

Male 287 279

Male-female gap -10 -13

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics

Change in 12th-Grade Reading Scores, by Percentile: 1992 and 2005

Percentile 1992 2005 Change

90th 333 333 0

75th 315 313 -2

50th 294 288 -6

25th 271 262 -9

10th 249 235 -14

All score changes from 1992 are statistically significant.

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics

Percentage of 12th-Graders Reading at or Above the Proficient Level

1992 2005 Change Rate of decline

40% 35% -5 pp -13%

pp = percentage points

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics

v

Foi adults, Piocient coiie-

sponds with a piose liteiacy scoie

of 340 oi gieatei (out of 500).

vi

Exceptions aie adults still in

high school and those with a GED

oi high school equivalency. In

both cases, scoie changes fiom

1992 to 2003 weie not statistically

signicant.

3. Reading prociency rates are stagnant or declining in adults of both genders

and all education levels.

Te peicentage of men who iead at a Piocient level has declined. Foi women,

the shaie of Piocient ieadeis has stayed the same.

v

Aveiage ieading scoies have declined in adults of viitually all education levels.

vi

Even among college giaduates, ieading piociency has declined at a 2023

iate.

4. Reading for pleasure correlates strongly with academic achievement.

Voluntaiy ieadeis aie bettei ieadeis and wiiteis than non-ieadeis.

Childien and teenageis who iead foi pleasuie on a daily oi weekly basis scoie

bettei on ieading tests than infiequent ieadeis.

Fiequent ieadeis also scoie bettei on wiiting tests than non-ieadeis oi

infiequent ieadeis.

12 To Read or Not To Read

Percentage of Adults Proficient in Reading Prose, by Gender

1992 2003 Change Rate of decline

Female 14% 14% 0 pp 0%

Male 16% 13% -3 pp -19%

Both genders 15% 13% -2 pp -13%

pp = percentage points

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics

Average Prose Literacy Scores of Adults, by Highest Level of Educational

Attainment: 1992 and 2003

Education level: 1992 2003 Change

Less than/some high school 216 207 -9

High school graduate 268 262 -6

Vocational/trade/business school 278 268 -10

Some college 292 287 -5

Associates/2-year degree 306 298 -8

Bachelors degree 325 314 -11

Graduate study/degree 340 327 -13

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics

Percentage of College Graduates Proficient in Reading Prose

1992 2003 Change Rate of decline

Bachelors degree 40% 31% -9 pp -23%

Graduate study/degree 51% 41% -10 pp -20%

pp = percentage points

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics

To Read or Not To Read 13

Almost every day

Once or twice a week

Once or twice a month

Never or hardly ever

302

292

285

274

Almost every day

Once or twice a week

Once or twice a month

Never or hardly ever

165

154

149

136

Average Reading Scores by Frequency of Reading for Fun

Grade 12 in 2005

Average Writing Scores by Frequency of Reading for Fun

Grade 12 in 2002

Reading scores range from 0 to 500.

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics

Writing scores range from 0 to 300.

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics

vii

Statistics Canada and OECD,

Learning a Living: First Results of

the Adult Literacy and Life Skills

Survey, 2005, 145.

viii

Te National Commission on

Wiiting, Writing: A Ticket to

Workor a Ticket Out: A Survey of

Business Leaders, 2004, 29, and

Writing: A Powerful Message from

State Government, 2005, 32.

C. Tnr Drciirs i Rroio Hvr Civic, Socii, o Ecooric

Irviic:ios

Advanced ieadeis acciue peisonal, piofessional, and social advantages. Decient

ieadeis iun highei iisks of failuie in all thiee aieas.

1. Employers nowrank reading and writing as top deciencies in newhires.

38 of employeis nd high school giaduates decient in ieading compiehen-

sion, while 63 iate this basic skill veiy impoitant.

Wiitten communications tops the list of applied skills found lacking in high

school and college giaduates alike.

One in ve U.S. woikeis iead at a lowei skill level than theii job iequiies.

vii

Remedial wiiting couises aie estimated to cost moie than $3.1 billion foi laige

coipoiate employeis and $221 million foi state employeis.

viii

14 To Read or Not To Read

Percentage of Employers Who Rate High School Graduates as Deficient

in Basic Skills

Writing in English 72%

Foreign languages 62%

Mathematics 54%

History/geography 46%

Government/economics 46%

Science 45%

Reading comprehension 38%

Humanities/arts 31%

English language 21%

Source: The Conference Board, Are They Really Ready to Work?, 2006

Percentage of Employers Who Rate Job Entrants as Deficient in Applied Skills

High school graduates deficient in: College graduates deficient in:

Written communication 81% Written communication 28%

Leadership 73% Leadership 24%

Professionalism/work ethic 70% Professionalism/work ethic 19%

Critical thinking/problem solving 70% Creativity/innovation 17%

Lifelong learning/self direction 58% Lifelong learning/self-direction 14%

Source: The Conference Board, Are They Really Ready to Work?, 2006

Rated Very Important by Employers

Percentage of employers who rate the following basic skills as very important for high school graduates:

Reading comprehension 63%

English language 62%

Writing in English 49%

Mathematics 30%

Foreign languages 11%

Source: The Conference Board, Are They Really Ready to Work?, 2006

2. Good readers generally have more nancially rewarding jobs.

Moie than 60 of employed Piocient ieadeis have jobs in management, oi in

the business, nancial, piofessional, and ielated sectois.

Only 18 of Basic ieadeis aie employed in those elds.

Piocient ieadeis aie 2.5 times as likely as Basic ieadeis to be eaining $850 oi

moie a week.

3. Less advanced readers report fewer opportunities for career growth.

38 of Basic ieadeis said theii ieading level limited theii job piospects.

Te peicentage of Below-Basic ieadeis who iepoited this expeiience was 1.8

times gieatei.

Only 4 of Piocient ieadeis iepoited this expeiience.

To Read or Not To Read 15

Percentage of Full-Time Workers by Weekly Earnings and Reading Level in 2003

$850$1,149 $1,150$1,449 $1,450$1,949 $1,950 or more Total earning $850

or more

Proficient 20% 13% 13% 12% 58%

Basic 12% 5% 2% 4% 23%

Below Basic 7% 3% 1% 2% 13%

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics

Percentage Employed in Management and Professional Occupations, by Reading

Level in 2003

Management, business Professional Total in either job

and financial and related category

Proficient 19% 42% 61%

Basic 8% 10% 18%

Below Basic 3% 4% 7%

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics

Percentage of Adults Who Said Their Reading Skills Limited Their Job

Opportunities, by Reading Level in 2003

A little Some A lot Total

Proficient 2% 1% 1% 4%

Basic 14% 15% 9% 38%

Below Basic 13% 22% 35% 70%

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics

ix

National Endowment foi the

Aits, e Arts and Civic Engage-

ment: Involved in Arts, Involved in

Life, 2006.

x

Ibid.

4. Good readers play a crucial role in enriching our cultural and civic life.

Liteiaiy ieadeis aie moie than 3 times as likely as non-ieadeis to visit

museums, attend plays oi conceits, and cieate aitwoiks of theii own.

Tey aie also moie likely to play spoits, attend spoiting events, oi do outdooi

activities.

18- to 34-yeai-olds, whose ieading iates aie the lowest foi any adult age gioup

undei 65, show declines in cultuial and civic paiticipation.

ix

5. Good readers make good citizens.

Liteiaiy ieadeis aie moie than twice as likely as non-ieadeis to volunteei oi do

chaiity woik.

x

Adults who iead well aie moie likely to volunteei than Basic and Below-Basic

ieadeis.

16 To Read or Not To Read

Percentage of Adults Who Volunteered, by Reading Level in 2003

Less than Once a week Total who

once a week or more volunteered

Proficient 32% 25% 57%

Basic 16% 15% 31%

Below Basic 8% 10% 18%

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics

Percentage of Literary Readers Who Volunteered in 2002

Literary readers Non-readers Gap between groups

43% 16% -27 pp

pp = percentage points

Source: National Endowment for the Arts

Participation Rates for Literary Readers in 2002

Literary readers Non-readers Gap between groups

Visit art museums 43% 12% -31 pp

Attend plays or musicals 36% 10% -26 pp

Attend jazz or classical concerts 29% 9% -20 pp

Create photographs, paintings, or writings 32% 10% -22 pp

Attend sporting events 44% 27% -17 pp

Play sports 38% 24% -14 pp

Exercise 72% 40% -32 pp

Do outdoor activities 41% 22% -19 pp

pp = percentage points

Source: National Endowment for the Arts

xi

Editoiial Piojects in Education,

Diplomas Count 2007: Ready for

What? Preparing Students for

College, Careers, and Life after

High School, Executive Summaiy.

84 of Piocient ieadeis voted in the 2000 piesidential election, compaied

with 53 of Below-Basic ieadeis.

6. Decient readers are far more likely than skilled readers to be high school

dropouts.

Half of Ameiicas Below-Basic ieadeis failed to complete high schoola

peicentage gain of 5 points since 1992.

One-thiid of ieadeis at the Basic level diopped out of high school.

Foi high school diopouts, the aveiage ieading scoie is 55 points lowei than foi

high school giaduatesand the gap has giown since 1992.

Tis fact is especially tioubling in light of iecent estimates that only 70 of

high school students eain a diploma on time.

xi

To Read or Not To Read 17

Percentage of Adults Who Voted in the 2000 Presidential Election, by 2003

Reading Level

Proficient 84%

Basic 62%

Below Basic 53%

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics

Percentage of Adults at or Below Basic Prose Reading Level Who Did Not

Complete High School: 1992, 2003

Prose reading level

Below Basic Basic

1992 2003 Change 1992 2003 Change

45% 50% +5 pp 38% 33% -5 pp

pp = percentage points

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics

Average Prose Reading Scores for Adult High School Graduates and Those Who

Did Not Complete High School: 1992, 2003

Prose reading score

Highest level of education 1992 2003 Change

Less than/some high school 216 207 -9

High school graduate 268 262 -6

Gap between groups -52 -55

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics

xii

U.S. Depaitment of Education,

National Centei foi Education

Statistics, Literacy Behind Bars:

Results from the 2003 National

Assessment of Adult Literacy

Prison Survey, 2007, 77.

7. Decient readers are more likely thanskilledreaders tobe out of the workforce.

Moie than half of Below-Basic ieadeis aie not in the woikfoice.

44 of Basic ieadeis lack a full-time oi pait-time jobtwice the peicentage of

Piocient ieadeis in that categoiy.

8. Poor reading skills are endemic in the prison population.

56 of adult piisoneis iead at oi below the Basic level.

Adult piisoneis have an aveiage piose ieading scoie of 25718 points lowei

than non-piisoneis.

Only 3 of adult piisoneis iead at a Piocient level.

Low ieading scoies peisist in piisoneis neaiing the end of theii teim, when

they aie expected to ietuin to family, society, and a moie pioductive life.

xii

18 To Read or Not To Read

Percentage of Adult Prisoners and Household Populations by 2003 Reading Level

Prose reading level Household Prison Gap

Below Basic 14% 16% *+2 pp

Basic 29% 40% +11 pp

Intermediate 44% 41% *-3 pp

Proficient 13% 3% -10 pp

* = not statistically significant

pp = percentage points

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics

Percentage of Adults Employed Full-Time or Part-Time, by 2003 Reading Level

Proficient 78%

Basic 56%

Below Basic 45%

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics

Conclusion

Self-iepoited data on individual behavioial patteins, combined with national test

scoies fiom the Depaitment of Education and othei souices, suggest thiee distinct

tiends: a histoiical decline in voluntaiy ieading iates among teenageis and young

adults, a giadual woisening of ieading skills among oldei teens, and declining pio-

ciency in adult ieadeis.

Te Depaitment of Educations extensive data on voluntaiy ieading patteins and

piose ieading scoies yield a fouith obseivation: fiequency of ieading foi pleasuie

coiielates stiongly with bettei test scoies in ieading and wiiting. Fiequent ieadeis

aie thus moie likely than infiequent oi non-ieadeis to demonstiate academic

achievement in those subjects.

Fiom the diveisity of data souices in this iepoit, othei themes emeige. Analyses

of voluntaiy ieading and ieading ability, and the social chaiacteiistics of advanced

and decient ieadeis, identify seveial disciepancies at a national level:

Less ieading foi pleasuie in late adolescence than in youngei age gioups

Declines in ieading test scoies among 17-yeai-olds and high school seniois in

contiast to youngei age gioups and lowei giade levels

Among high school seniois, a widei iift in the ieading scoies of advanced and

decient ieadeis

A male-female gap in ieading pioclivity and achievement levels

A shaip divide in the ieading skills of incaiceiated adults veisus non-piisoneis

Gieatei academic, piofessional, and civic benets associated with high levels of

leisuie ieading and ieading compiehension

Longitudinal studies aie needed to conimand monitoi the eects of these diei-

ences ovei time. Futuie ieseaich also could exploie factois such as income, ethnicity,

iegion, and iace, and howthey might altei the ielationship between voluntaiy iead-

ing, ieading test scoies, and othei outcomes. Ciitically, fuithei studies should weigh

the ielative eectiveness and costs and benets of piogiams to fostei lifelong ieading

and skills development. Foi instance, such ieseaich could tiace the eects of elec-

tionic media and scieen ieading on the development of ieadeis in eaily childhood.

Recent studies of Ameiican time-use and consumei expendituie patteins high-

light a seiies of choices luiking in the question To iead oi not to iead? Te futuie

of ieading iests on the daily decisions Ameiicans will continue to make when con-

fionted with an expanding menu of leisuie goods and activities. Te impoit of these

national ndings, howevei, is that ieading fiequently is a behavioi to be cultivated

with the same zeal as academic achievement, nancial oi job peifoimance, and global

competitiveness.

Technical Note

Tis iepoit piesents some of the most ieliable and cuiiently available statistics on

Ameiican ieading iates, liteiacy, and ieadei chaiacteiistics. No attempt has been

made to exploie methods foi ieading instiuction, oi to delve into iacial, ethnic, oi

income tiaits of voluntaiy ieadeis, though age, gendei, and education aie discussed

at vaiious points in the analyses. Te majoiity of the data stemfiomlaige, nationally

iepiesentative studies completed aftei the 2004 publication of the NEAs Reading at

Risk iepoit. Unless a footnote is piovided, souices foi all data in this Executive Sum-

To Read or Not To Read 19

maiy aie given with each accompanying chait oi table. All adult ieading scoies and

piociency iates iefei to the Depaitment of Educations piose liteiacy categoiy.

Caution should be used in compaiing iesults fiomthe seveial studies cited in this

publication, as the studies use dieient methodologies, suivey populations, iesponse

iates, and standaid eiiois associated with the estimates, and the studies often weie

designed to seive dieient ieseaich aims. No denite causal ielationship can be made

between voluntaiy ieading and ieading piociency, oi between voluntaiy ieading,

ieading piociency, and the ieadei chaiacteiistics noted in the iepoit. Finally, except

wheie book ieading oi liteiaiy ieading iates aie specically mentioned, all iefeiences

to voluntaiy ieading aie intended to covei all types of ieading mateiials.

Oce of Reseaich & Analysis

National Endowment foi the Aits

20 To Read or Not To Read

You might also like

- Unit 2 Progress Test B: GrammarDocument4 pagesUnit 2 Progress Test B: GrammarАртем Степанец100% (4)

- Citizenship Test Questio SDocument65 pagesCitizenship Test Questio SAmit Mehta100% (1)

- More Than Money: How Economic Inequality Affects . . . EverythingFrom EverandMore Than Money: How Economic Inequality Affects . . . EverythingNo ratings yet

- Hive Mind: How Your Nation’s IQ Matters So Much More Than Your OwnFrom EverandHive Mind: How Your Nation’s IQ Matters So Much More Than Your OwnRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Hollowed Out: A Warning about America's Next GenerationFrom EverandHollowed Out: A Warning about America's Next GenerationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- MR Darcy's Diary: Maya SlaterDocument14 pagesMR Darcy's Diary: Maya Slatershush10100% (1)

- Byrne RefugeDocument31 pagesByrne RefugeRyan ByrneNo ratings yet

- Teaching DemocracyDocument20 pagesTeaching DemocracyDani ZsigovicsNo ratings yet

- No Child Left Behind3Document9 pagesNo Child Left Behind3carolinecovellNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Social ProblemsDocument5 pagesResearch Paper Social Problemsh02ngq6c100% (1)

- Mayor's Summit of The Child: Stojanna HollisDocument8 pagesMayor's Summit of The Child: Stojanna HollisstojannaNo ratings yet

- Academic Achievement Core - Wake 2017Document57 pagesAcademic Achievement Core - Wake 2017Brandon RogersNo ratings yet

- High Quality Civic Education:: What Is It and Who Gets It?Document6 pagesHigh Quality Civic Education:: What Is It and Who Gets It?gpnasdemsulselNo ratings yet

- Chartering Through Barriers Final ReportDocument8 pagesChartering Through Barriers Final ReportveasnahoyNo ratings yet

- Connell Youth Dev BookDocument326 pagesConnell Youth Dev BookAdam Leon CooperNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement For Homeless YouthDocument4 pagesThesis Statement For Homeless Youthheatheredwardsmobile100% (2)

- Research Paper Topics About PovertyDocument6 pagesResearch Paper Topics About Povertyafeaoebid100% (1)

- Poverty Thesis PaperDocument8 pagesPoverty Thesis Paperjenwilsongrandrapids100% (2)

- Social Problems Research Paper IdeasDocument7 pagesSocial Problems Research Paper Ideasnadevufatuz2100% (1)

- Thesis Statement On Poverty in AmericaDocument6 pagesThesis Statement On Poverty in Americadawnnelsonmanchester100% (1)

- The Schooled Society: The Educational Transformation of Global CultureFrom EverandThe Schooled Society: The Educational Transformation of Global CultureRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Research Paper in PovertyDocument7 pagesResearch Paper in Povertyc9kb0eszNo ratings yet

- Westheimer Teaching DemocracyDocument17 pagesWestheimer Teaching DemocracyElize FontesNo ratings yet

- Social Issue Research Paper ExampleDocument7 pagesSocial Issue Research Paper Examplevvgnzdbkf100% (1)

- Teaching Democracy:: What Schools Need To DoDocument19 pagesTeaching Democracy:: What Schools Need To DoLTTuangNo ratings yet

- Ydd2000 PDFDocument326 pagesYdd2000 PDFharoldNo ratings yet

- Day 4Document10 pagesDay 4wkurlinkus7386No ratings yet

- Failing Liberty 101: How We Are Leaving Young Americans Unprepared for Citizenship in a Free SocietyFrom EverandFailing Liberty 101: How We Are Leaving Young Americans Unprepared for Citizenship in a Free SocietyNo ratings yet

- Our Schools and Education: the War Zone in America: Truth Versus IdeologyFrom EverandOur Schools and Education: the War Zone in America: Truth Versus IdeologyNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Causes of PovertyDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Causes of Povertyxactrjwgf100% (1)

- 2017 Lee Annual ReportDocument20 pages2017 Lee Annual ReportSenator Mike LeeNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement For Poverty Research PaperDocument5 pagesThesis Statement For Poverty Research Papergz3ezhjc100% (1)

- Sociology Viva NotesDocument4 pagesSociology Viva NotesTaniaNo ratings yet

- Issue Platform 15Document19 pagesIssue Platform 15asdf789456123No ratings yet

- Vietnamese Youth LifestyleDocument9 pagesVietnamese Youth Lifestylenamphong_vnvnNo ratings yet

- Parenting Practices, Teenage Lifestyles, and Academic Achievement Among African American ChildrenDocument9 pagesParenting Practices, Teenage Lifestyles, and Academic Achievement Among African American ChildrenAin KhadirNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Social Issue TopicsDocument8 pagesResearch Paper Social Issue Topicsafnhlmluuaaymj100% (1)

- The Future of Democracy: Developing the Next Generation of American CitizensFrom EverandThe Future of Democracy: Developing the Next Generation of American CitizensRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Social Issues of SocietyDocument85 pagesSocial Issues of SocietyArcely GundranNo ratings yet

- Greater Expectations: Nuturing Children's Natural Moral GrowthFrom EverandGreater Expectations: Nuturing Children's Natural Moral GrowthRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Literasi MathematisDocument248 pagesLiterasi MathematisRyna WidyaNo ratings yet

- Childhood, Youth, and Social Work in Transformation: Implications for Policy and PracticeFrom EverandChildhood, Youth, and Social Work in Transformation: Implications for Policy and PracticeNo ratings yet

- Get Out Now: Why You Should Pull Your Child from Public School Before It's Too LateFrom EverandGet Out Now: Why You Should Pull Your Child from Public School Before It's Too LateNo ratings yet

- Kids R UsDocument281 pagesKids R UsWellington PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Defense PaperDocument4 pagesDefense PaperBrittany StallworthNo ratings yet

- Young Minds Wasted: Reducing Poverty By Enchancing Intelligence, In Known Ways.From EverandYoung Minds Wasted: Reducing Poverty By Enchancing Intelligence, In Known Ways.No ratings yet

- Poverty Research Paper ConclusionDocument6 pagesPoverty Research Paper Conclusionjuzel0zupis3100% (1)

- Social IsssueDocument15 pagesSocial IsssueRonak GoswamiNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Youth CultureDocument4 pagesResearch Paper Youth Culturegwfdurbnd100% (3)

- DEPRESSION and YOUTH Ge PresentationDocument23 pagesDEPRESSION and YOUTH Ge PresentationFadilNo ratings yet

- Timeline of The Destruction of America Through EducationDocument48 pagesTimeline of The Destruction of America Through EducationVincit Omnia VeritasNo ratings yet

- New Frontiers for Youth Development in the Twenty-First Century: Revitalizing and Broadening Youth DevelopmentFrom EverandNew Frontiers for Youth Development in the Twenty-First Century: Revitalizing and Broadening Youth DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- Poverty Research Paper PDFDocument5 pagesPoverty Research Paper PDFgsrkoxplg100% (1)

- The Deaf: Their Position in Society and the Provision for Their Education in the United StatesFrom EverandThe Deaf: Their Position in Society and the Provision for Their Education in the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Thesis About Out of School Youth in The PhilippinesDocument5 pagesThesis About Out of School Youth in The PhilippinesWriteMyPaperForMeIn3HoursSingapore100% (2)

- Overschooled BUT Undereducated: John AbbottDocument12 pagesOverschooled BUT Undereducated: John AbbottNige CookNo ratings yet

- Poverty Research PaperDocument7 pagesPoverty Research Paperiangetplg100% (1)

- Defense PaperDocument5 pagesDefense PaperBrittany StallworthNo ratings yet

- Social Skills: The Modern Skill for Success, Fun, and Happiness Out of LifeFrom EverandSocial Skills: The Modern Skill for Success, Fun, and Happiness Out of LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Causes of Poverty Thesis StatementDocument5 pagesCauses of Poverty Thesis Statementoabfziiig100% (2)

- Research Papers On Homelessness and Mental IllnessDocument4 pagesResearch Papers On Homelessness and Mental Illnessc9snjtdxNo ratings yet

- Agents of Child SocializationDocument21 pagesAgents of Child SocializationCamille MoralesNo ratings yet

- Topik Kamu: - Cognitive Dissonance - Expectancy Violation TheoryDocument16 pagesTopik Kamu: - Cognitive Dissonance - Expectancy Violation Theoryshush10No ratings yet

- What Is ForestDocument3 pagesWhat Is Forestshush10No ratings yet

- Habermas Critical Theory - July 17th2008Document28 pagesHabermas Critical Theory - July 17th2008shush10No ratings yet

- Expectancy Violation TheoryPP 2Document12 pagesExpectancy Violation TheoryPP 2shush10100% (1)

- Map - Comm.broadcasting - Fa11.lckDocument1 pageMap - Comm.broadcasting - Fa11.lckshush10No ratings yet

- Committee Member Should Careful The Importance of DetailsDocument2 pagesCommittee Member Should Careful The Importance of Detailsshush10No ratings yet

- Syllabus - Global CommunicationDocument3 pagesSyllabus - Global Communicationshush10No ratings yet

- Photography Contest Rules and RegulationsDocument3 pagesPhotography Contest Rules and Regulationsshush10No ratings yet

- Terms and Conditions of Drawing CompetitionDocument1 pageTerms and Conditions of Drawing Competitionshush10No ratings yet

- Communication, Media, Film and Cultural Studies 2008Document25 pagesCommunication, Media, Film and Cultural Studies 2008shush10No ratings yet

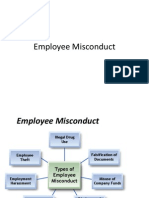

- Employee MisconductDocument14 pagesEmployee Misconductshush10No ratings yet

- Evaluating Source SearchDocument6 pagesEvaluating Source Searchshush10No ratings yet

- BA (Hons) Television1Document15 pagesBA (Hons) Television1shush10No ratings yet

- DSSB ClerkDocument4 pagesDSSB Clerkjfeb40563No ratings yet

- REVIEWER Gen001Document2 pagesREVIEWER Gen001Jessie James Alberca AmbalNo ratings yet

- Class-Based ModelingDocument1 pageClass-Based Modelingiedil_dinNo ratings yet

- From Discrete-Point Test To Integrative AssessmentDocument3 pagesFrom Discrete-Point Test To Integrative AssessmentRelec RonquilloNo ratings yet

- Direct and Indirect Object PronounsDocument11 pagesDirect and Indirect Object PronounsHamish HaldaneNo ratings yet

- Report Writing For Data Science in R - Roger D. PengDocument120 pagesReport Writing For Data Science in R - Roger D. PengAlvaro Enrique CastañedaNo ratings yet

- Modal VerbsDocument5 pagesModal Verbsaborruza65No ratings yet

- 4SP0 02 Rms 20110824aDocument9 pages4SP0 02 Rms 20110824aEinsteinNo ratings yet

- Oracle® Database: Concepts 11g Release 2 (11.2)Document454 pagesOracle® Database: Concepts 11g Release 2 (11.2)kterkalNo ratings yet

- рт past perfectDocument4 pagesрт past perfectЮлия МунNo ratings yet

- Active and Passive VoiceDocument30 pagesActive and Passive VoiceNyemeck JamesNo ratings yet

- Business Communication - EnG301 Power Point Slides Lecture 13Document23 pagesBusiness Communication - EnG301 Power Point Slides Lecture 13Friti FritiNo ratings yet

- Because I Could Not Stop For Death Emily DickinsonDocument21 pagesBecause I Could Not Stop For Death Emily DickinsonNur Azizah RahmanNo ratings yet

- English Tenses Manual: Turi4BDocument10 pagesEnglish Tenses Manual: Turi4BRichy HernándezNo ratings yet

- HW5e Upper Int International WordlistDocument15 pagesHW5e Upper Int International WordlistBossan MmmNo ratings yet

- Analysing The Poem - I WonderDocument1 pageAnalysing The Poem - I WonderYinXin LowNo ratings yet

- Final Art Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesFinal Art Lesson Planapi-665401288No ratings yet

- Adjective Clauses: That, Which, Whom, Whose, Where, and WhenDocument3 pagesAdjective Clauses: That, Which, Whom, Whose, Where, and WhenKristin SitanggangNo ratings yet

- Latin List of Logic FallaciesDocument34 pagesLatin List of Logic FallaciesMark DicksonNo ratings yet

- Reiki: The JO SymbolDocument5 pagesReiki: The JO SymbolJames Deacon100% (1)

- Community Resources Presentation AssignmentDocument5 pagesCommunity Resources Presentation AssignmentMonserrath DominguezNo ratings yet

- Rubrics-LabReport BMS 531 FEB JUNE 2020Document1 pageRubrics-LabReport BMS 531 FEB JUNE 2020ShahNo ratings yet

- Application LetterDocument3 pagesApplication LetterUtkarsh AnandNo ratings yet

- LidijaDocument1 pageLidijamilance93100% (2)

- Production of SpeechDocument12 pagesProduction of Speechaika.kadyralievaNo ratings yet

- Cross Culture Language Learning BookDocument84 pagesCross Culture Language Learning BookkumarsathishsNo ratings yet

- Commonly Confused WordsDocument59 pagesCommonly Confused WordsHeidi DizonNo ratings yet