Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ending Deindustriasdf Dfasdflisation

Uploaded by

Shahimulk KhattakOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ending Deindustriasdf Dfasdflisation

Uploaded by

Shahimulk KhattakCopyright:

Available Formats

Ending deindustrialisation

By Mubarak Zeb Khan | 6/10/2013 12:00:00 AM THOUGH he comes from an industrial background, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif will face one of his toughest challenges in reviving the country`s industrial growth. This may not be an easy job, as deindustrialisation is deep-rooted. For the past few decades, the manufacturing sector has been beset with a host of problems, including an absence of an industrial policy, a crippling energy crisis, and a narrow industrial base. Policies pursued by previous finance ministers Shaukat Aziz, Shaukat Tareen, and Dr Hafeez Shaikh only encouraged and facilitated the services industry, particularly the consumption sector. Nothing substantial has been done for the manufacturing sector, and the role of the industries ministry was confined to monitoring prices, and it remained focused on a few industries, like sugar, fertiliser, automobiles etc. Industries ministers were found to be running the affairs of utility stores to `stabilise prices` in the past few years. Meanwhile, the size of the industrial sector in the overall economy has remained stagnant. For industrial development, the PML-N will have to finalise the industrial policy, coupled with fiscal incentives to resolve energy problem, and also encourage the use of alternate sources of energy through incentives like tax breaks. It should club together all ministries created for looking after the affairs of various industries, like the ministries of industry, production, textile and commerce, into one single ministry `ministry of commerce and industry,` as is the case in countries like India. A single ministry deals with production as well as exports in these countries. And while a draft National Industrial Policy was evolved in May 2011, it was not implemented. The policy document is apparently agood piece of research, and comes up with some ambitious targets, like eight per cent industrial growth per annum (with interrupted power and gas supply), creation of more than four million new jobs, and 100 per cent value addition in the manufacturing sector. It further claims that the policy will turn P a k i s t a n into a `world factory` in the next 10 years. The document also seeks to double the manufacturing output in the next 10 years, and expand the stagnant industrial employment from the current 13 per cent of the country`s total labour force to 20 per cent.While this looks good on paper, it raises the question as to how will the targets be achieved. However, these targets can be revisited to be fine tuned. Manufacturing has suffered mainly because of energy shortages, a sharp drop in foreign direct

investment into the sector, and a slump in demand in the international market. The existing manufacturing sector is unable to utilise the maximum possible capacity of the installed capacity due to the energy crisis. Statistics compiled by the ministry of industries show that capacity utilisation at 37 large-scale industries ranges between 30-60 per cent. There is a great potential for production of alternate energy sources, given that fiscal and monetary incentives are extended to serious investors from the industrial sector. Coalbased captive power generation is one of the ways to produce cheap electricity and gas for industries. While other sources for alternate energy must also be tapped, captivepower generation is comparatively more cost-effective and efficient. In the shorter term, the government can halve the sales tax on petrol, high speed diesel oil/furnace oil in the budget from 16 per cent to eight per cent. As fuel consumption is price elastic, this might lessen the reliance on gas as a source of fuel, thus making freeing it up for industrial purposes. Coal-based captive power generation, like power generation through `coal gasification,` can be encouraged by giving a five-year tax break to industrial units to make up the cost of gasifiers particularly to textile and steel re-rolling mills. The tax holiday may be linked with a six-month deadline for switching to captive power generation. This will not only provide cheap, round-theclock energy to textile industries, but also spare energy for other sectors. On average, one kilogramme of coal produces 2.2 m3 of coal gas and one kilowatt hour of electricity. If the price of coal is Rs6,000 per tonne, oneunit of electricity produced from it will cost approximately Rs7.5. Contrary to this, industries are buying electricity from the grid station at around Rs14 to Rs16 per unit. So, the off-grid electricity is much cheaper, while long transmission line costs are also saved. Similarly, industries that use boilers for processing textile, leather, food processing, sugar and chemicals need to be encouraged to pursue solar power generation to cut their costs. However, this switchover is only viable through various incentives that the government should consider in the budget. The clubbing together of multiple ministries into one industries ministry will also help to resolve governance issues like overlapping policies and pressure by interest groups to a large extent,. However, if no corrective measures are taken, exports of the manufacturing sector will continue to decline, and sufficient job creation will remain a distant goal.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Honda S2000 (00-03) Service ManualDocument0 pagesHonda S2000 (00-03) Service Manualmcustom1No ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Manage Risks and Seize OpportunitiesDocument5 pagesManage Risks and Seize Opportunitiesamyn_s100% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Islamiat Solved MCQS 2005 To 2011Document8 pagesIslamiat Solved MCQS 2005 To 2011alibutt000192% (12)

- Maintenance Handbook On Bonding Earthing For 25 KV AC Traction SystemsDocument46 pagesMaintenance Handbook On Bonding Earthing For 25 KV AC Traction SystemsPavan100% (1)

- QKNA For Mining GeologistDocument10 pagesQKNA For Mining GeologistAchanNo ratings yet

- ACFM Inspection Procedure PDFDocument40 pagesACFM Inspection Procedure PDFNam DoNo ratings yet

- Meetings Bloody MeetingsDocument4 pagesMeetings Bloody MeetingsMostafa MekawyNo ratings yet

- GM Construction Leads Rs 8140 Crore PCII C2C3 Recovery ProjectDocument24 pagesGM Construction Leads Rs 8140 Crore PCII C2C3 Recovery ProjectAnuj GuptaNo ratings yet

- Astm Peel TestDocument2 pagesAstm Peel TestIvander GultomNo ratings yet

- EssaysddddddDocument3 pagesEssaysddddddShahimulk KhattakNo ratings yet

- Application For Allowing Montly Stipend ShahimulkDocument1 pageApplication For Allowing Montly Stipend ShahimulkShahimulk KhattakNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Affairs PrintjDocument11 pagesPakistan Affairs PrintjShahimulk KhattakNo ratings yet

- HungryDocument2 pagesHungryShahimulk KhattakNo ratings yet

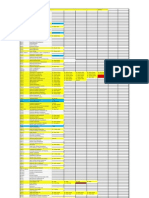

- Monthly Fee - XLSXHJGGJHGJGJGJGJHJHJHGJHGJGJGJGJHGJGGJHJHGJGJGH JHGJHGHJGJHJGHJGJGJGJDocument3 pagesMonthly Fee - XLSXHJGGJHGJGJGJGJHJHJHGJHGJGJGJGJHGJGGJHJHGJGJGH JHGJHGHJGJHJGHJGJGJGJShahimulk KhattakNo ratings yet

- Six-Year Study of Colorectal Carcinoma at a Tertiary Hospital in SindhDocument3 pagesSix-Year Study of Colorectal Carcinoma at a Tertiary Hospital in SindhShahimulk KhattakNo ratings yet

- Computer Communications and Networks (Ccnet) : Assignment No 1Document2 pagesComputer Communications and Networks (Ccnet) : Assignment No 1Shahimulk KhattakNo ratings yet

- Atomisation of SojkljljlkjkljlkcietyDocument3 pagesAtomisation of SojkljljlkjkljlkcietyShahimulk KhattakNo ratings yet

- Alliance Politics in PakistanDocument27 pagesAlliance Politics in PakistanShahimulk KhattakNo ratings yet

- VocadadsadfasDocument32 pagesVocadadsadfasShahimulk KhattakNo ratings yet

- Mohammad Ali Jinnah University, Islamabad. Control Systems LabDocument40 pagesMohammad Ali Jinnah University, Islamabad. Control Systems LabShahimulk KhattakNo ratings yet

- MUSLIM SCIENTISTSDocument34 pagesMUSLIM SCIENTISTSinfiniti786No ratings yet

- Everbchf Yday Scienfasdfasdfasdfasd Fasdf Asdfasdf Asdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasdface 2002Document5 pagesEverbchf Yday Scienfasdfasdfasdfasd Fasdf Asdfasdf Asdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasdface 2002Shahimulk KhattakNo ratings yet

- Lec Week3asfasdfasdfDocument3 pagesLec Week3asfasdfasdfShahimulk KhattakNo ratings yet

- CSS Suggested BooksDocument4 pagesCSS Suggested Booksshakeel_pak75% (4)

- Assignment PrecDocument1 pageAssignment PrecShahimulk KhattakNo ratings yet

- Fasdfasdfscience 2000sdDocument4 pagesFasdfasdfscience 2000sdShahimulk KhattakNo ratings yet

- The Ga SLJDF Alsjdf Lsaj Ldfja LSDF Jalsdjflka Jdfljskdlfja Llobal Power Shift To Asia KojloihihklhkjhkhkhkhjkhkhkhkjhkhkjhkhkjDocument6 pagesThe Ga SLJDF Alsjdf Lsaj Ldfja LSDF Jalsdjflka Jdfljskdlfja Llobal Power Shift To Asia KojloihihklhkjhkhkhkhjkhkhkhkjhkhkjhkhkjShahimulk KhattakNo ratings yet

- Css Guidanc DfadsfsadfsdfeDocument1 pageCss Guidanc DfadsfsadfsdfeShahimulk KhattakNo ratings yet

- Observations of Examiners On Performance of Candidates in Writtedfasdfan Part of CSS Examination 2006Document10 pagesObservations of Examiners On Performance of Candidates in Writtedfasdfan Part of CSS Examination 2006Shahimulk KhattakNo ratings yet

- EEDocument9 pagesEEShahimulk KhattakNo ratings yet

- MY Current Affairs NotesDocument127 pagesMY Current Affairs NotesShahimulk Khattak100% (2)

- QuotaasdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasfsadftionsDocument2 pagesQuotaasdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasdfasfsadftionsShahimulk KhattakNo ratings yet

- Circular No. 27 - Olympiad ScheduleDocument2 pagesCircular No. 27 - Olympiad Schedulerishu ashiNo ratings yet

- Training Nathpa Jhakri SJVNLDocument53 pagesTraining Nathpa Jhakri SJVNLParas Thakur100% (3)

- Caterpillar 307 CSB Technical SpecificationsDocument3 pagesCaterpillar 307 CSB Technical Specificationsdale100% (22)

- Vivek Pal-2Document36 pagesVivek Pal-2Vivek palNo ratings yet

- Baremos Espanoles CBCL6-18 PDFDocument24 pagesBaremos Espanoles CBCL6-18 PDFArmando CasillasNo ratings yet

- ASHIDA Product CatalogueDocument4 pagesASHIDA Product Cataloguerahulyadav2121545No ratings yet

- Factory Overhead Variances: Flexible Budget ApproachDocument4 pagesFactory Overhead Variances: Flexible Budget ApproachMeghan Kaye LiwenNo ratings yet

- Gate Study MaterialDocument89 pagesGate Study MaterialMansoor CompanywalaNo ratings yet

- FS7M0680, FS7M0880: Fairchild Power Switch (FPS)Document19 pagesFS7M0680, FS7M0880: Fairchild Power Switch (FPS)Arokiaraj RajNo ratings yet

- Extractor de Pasadores de OrugaDocument2 pagesExtractor de Pasadores de OrugaErik MoralesNo ratings yet

- Second Year Hall Ticket DownloadDocument1 pageSecond Year Hall Ticket DownloadpanditphotohouseNo ratings yet

- VingDocument8 pagesVingNguyễnĐắcĐạt100% (1)

- BDS Maschinen MABasicDocument4 pagesBDS Maschinen MABasicJOAQUINNo ratings yet

- Iwss 31 Win en AgDocument237 pagesIwss 31 Win en AgmarimiteNo ratings yet

- Ryu RingkasanDocument20 pagesRyu RingkasanBest10No ratings yet

- Coupled Scheme CFDDocument3 pagesCoupled Scheme CFDJorge Cruz CidNo ratings yet

- Generator Protection Unit, GPU-3 Data Sheet Generator Protection Unit, GPU-3 Data SheetDocument11 pagesGenerator Protection Unit, GPU-3 Data Sheet Generator Protection Unit, GPU-3 Data SheetJhoan ariasNo ratings yet

- Mobil Nuto H Series TdsDocument2 pagesMobil Nuto H Series TdswindiNo ratings yet

- RapidAnalytics ManualDocument23 pagesRapidAnalytics ManualansanaNo ratings yet

- Po Ex en 170413 WebDocument1 pagePo Ex en 170413 Webswordleee swordNo ratings yet

- Wall-Mounting Speakers EN 54Document5 pagesWall-Mounting Speakers EN 54Mauricio Yañez PolloniNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Pre Bid MeetingDocument23 pagesPresentation On Pre Bid MeetinghiveNo ratings yet