Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Networked City and Society: Consciousness With A

Uploaded by

pellinniOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Networked City and Society: Consciousness With A

Uploaded by

pellinniCopyright:

Available Formats

Networked City and Society

Federico Casalegno and Pelin Arslan

Rethinking urbanism in a sustainable way promotes social and economic inclusion as well as environmental consciousness with an aim of creating resilient cities. At the core of the idea of sustainable cities is the notion of solving urban problems from a holistic approach analyzing overlapping issues, understanding co-relations and foreseeing long lasting solution strategies through collaboration with various actors in the urban system.

Sustainable cities are also connected cities, employing ubiquitous, networked intelligence to ensure not only the efficient and responsible use of the scarce resources particularly energy and water that are required for a citys operation, together with the effective management of waste products that a city produces, such as carbon emissions to the atmosphere, but also the democratization of individuals participative ideas through media locative tools. The principal evolutionary eras here are:

Skeletons and skins. The earliest cities consisted of little more than skeleton and skin. They provided walls, floors, and roofs for shelter and protection, in combination with simple structural skeletons to hold them up. The intelligence needed to operate these cities resided in the heads of their inhabitants.

Mechanical metabolisms. In the industrial era, urban networks multiplied, differentiated, and grew in scale. Furthermore, they added mechanical metabolic systems and massive infrastructures to the skeletons and skins that they had traditionally provided. These systems then became major consumers of energy and producers of waste and pollution.

Electronic nervous systems. At the dawn of the electronic era, buildings and cities began to develop primitive nervous systems. Telegraph, telephone, and radio communication systems provided the first artificial nerves. These allowed architectural and urban systems to develop simple reflexes and feedback loops.

Internet era. In this era, the primitive nervous systems rapidly evolved into something approximating the advanced nervous systems of higher organisms. Ubiquitous digital networks supplanted the older analog networks and formed a new kind of urban infrastructure. Distributed systems of networked computers and server farms became the brains of cities. Pervasive sensing connected vast, new streams of data about urban activities to these brains. In future, the flows of resources into cities, the processing and distribution of materials, energy, and products, the coordination of the actions of individuals and organizations, and the eventual removal or recycling of waste can be increasingly informed, coordinated, and controlled by the new, rapidly growing, digital nervous systems.

Informed, responsible choices In our digitally networked, information-saturated era, ignorance of the consequences can be no excuse for ill-considered actions. It is increasingly possible to keep close track of our energy, water, and carbon footprints so that we can evaluate the sustainability consequences of our daily choices and actions. We have, at our fingertips, the tools and computation power to enable participation in sophisticated new fields, such as media, learning and wellbeing. Connected sustainable cities will encourage new forms of personal and group responsibility, and will establish powerful incentives to meet those responsibilities.

Like individuals, government institutions and businesses be they small or medium enterprises, or large corporations also have responsible choices to make. The success of a connected sustainable city depends on coordinated policy and action in the development and introduction of information and communication technologies. Governments at every level (federal, regional, municipal) need to adopt policies and regulations that promote such choices. Worldwide organizations also play a crucial role, and are especially important in fostering the development of connected sustainable cities and social sustainability.

The next generation of ICT tools New tools and applications are becoming available that make it less expensive, easier, and more effective than ever to coordinate collective action among people that can promote sustainable development and behavior. Often referred to as Web 2.0, these

technologies allow easier knowledge and information sharing, both crucial to the development of connected sustainable cities. Boyd (2009) and Shirky (2008) argue that the ease with which we can now connect, communicate, produce, share, replicate, locate and distribute information has had, and continues to have, a profound impact on our social, cultural and technological practices. On these emerging collaborative platforms, people can share and capitalize on lessons learned from best practices around the world. These types of tools can advance the rise of new bottom-up cultures of decision-making and promote civic engagement on topics of great importance, encouraging people to get involved and take action locally and on a global level.

As mobile devices with high-quality recording abilities proliferate, production of media content that is then uploaded, shared, and disseminated on social networks is becoming increasingly common. The intellectual and creative process inherent in media creation lends itself well towards engaging people within their communities to discover, explore, contribute and discuss issues around sustainability. This motivates participants to explore related topics in their local environment and consequently creates trust among government, people and cities.

Locast: Location-based Open Platform Locast platform explores new ways to implement information and communication technologies to cities and urban areas. Locast technology developed by the MIT Mobile Experience Lab allows a realization of this aim through different ways of achieving

sustainable urbanism: creating new cultural and social expressions, collaborative problem solving abilities, and civic engagement. Locast is an open locative-media platform, http://locast.mit.edu/, that combines web and mobile applications to allow geo-located media production and interaction. The Locast platform consists of three main components. Locast Web: the web-based interface, Locast core: the backend and API, and Locast Mobile: an Android-based mobile application. Locast technology is an integrated platform that combines mobile and web tools to enable users creating individual and collective narratives, disseminating content and creating community related conversations. People produce their own media elements through Locast mobile and web application and share their activities on a location-based map in real time. The Locast framework allows people to produce user generated content with geo-locative information and share their point of view on a participatory media platform. This social platform helps people, communities, and entities to explore new opportunities through social interaction in the Locast community and enable to exchange ideas with decision makers. The outcomes of Locast tool aims to improve connections between people, their social, cultural and physical spaces. This framework enables people to share their knowledge practices and collaborate in content generation to generate more democratic and collaborative environments. Locast technology has been used to address various issues and provide insights into current practice approaches in sustainable urbanism: civic engagement, capturing memories, and participatory learning. As an example in civic engagement as citizen

journalism practice, Locast Civic Media aims to engage citizenship in the process of collecting, reporting and disseminating news and information related to the urban environment. The platform incentivizes citizens proactive role through Locast open publishing tools, community self-regulation, social circulation of content, collaborative authoring as well as other production tools to improve the dynamics of an individuals works, conversations and collaborations.

The emphasis is on bringing together urban conversations with civic knowledge sharing practices for building information-based communities. Nelimarkka (2008) and Rheingold (2002) stated that mobile communication is becoming an effective instrument to strengthen civic bonds through the empowerment of individuals, the creation of ad-hoc networks and the proliferation of information. Locast mobile application enables the user to create street reports (casts) through video and audio content and decide whether to produce them individually or to involve peers in large scale reports on a specific topic and/or urban area projects. Casts and projects are created, collected and shared in real time on Locast websites where the entire members community can join the conversation with comments and further casts. The Locast Civic Media project has been deployed in Porto Alegre, Brasil with 25 media and communication students and 11 reporters. The participants were encouraged to freely use Locast to explore as many urban scenarios as possible according to personal interests and relations with the city spaces. The list of topics contained although were not limited to social and cultural aspects regarding city neighborhoods, local communities, ongoing

grassroots activities, subcultures, and popular events. Various types of media forms were also created from life capture, reports, interviews, breaking news to coverage, point of view narrations, investigations and sequential narrations. The participants had the opportunity to report news in their local area in real time and share problems with policy makers, and citizens. Another practiced approach to citizen as street smart mapper is the Locast Youth Mapping project which explores mobile and web tools to help youth in Rio de Janeiro to build impactful, communicative digital maps reporting problems in their community. MIT Mobile Experience Lab collaborated with UNICEFs Social and Civic Media section the Public Laboratory for Open Technology and Science (PLOTS) to develop the mapping tools. The project uses traditional media combined with new technologies including social networking tools, SMS and digital mapping to empower the youth to play an active role in society. Through a mobile phone application, youth produce a real-time portrait of their community creating geo-located photos and videos, organized as thematic maps. As a result of deploying the project in Rio de Janeiro in a one week timeframe, the main issues to emerge were as following: 374 reports on walking hazards, accumulation of garbage, sewage problems, collapse risk, power line problems, faulty stairs. These outcomes are an example of participative actions resulting in requests for governmental action leading to community benefits.

The mapping exercise enabled young people to contribute to raising awareness about the vulnerabilities they face in their community and to preventative planning. . Participants played an active role in identifying and communicating risks to local officials, thereby taking ownership in the process. The project showed that youth-led digital mapping is a compelling tool to articulate adolescents concerns on social and environmental topics to local officials. The initiative generated positive outcomes that directly impact the lives of young people in favelas. It increased the advocacy capacity of community actors, drew visibility to existing challenges and created off-line community changes. In addition, it contributed to more inclusive, secure, and participatory actions aimed at reducing risks and disparities in the city.

Another approach to improve sustainability patterns in an urban environment is to enable learning and developing awareness on local issues. In collaboration with the Museum of Science in Trento- Italy, Locast H2flow illustrates how a locative participatory media platform has the potential to strengthen connections between people, places, and information on local and regional environmental issues. The project was designed around the circumstances and contexts of this region, which feature glaciers that are melting at an alarming rate. The area is rich in natural water resources as well as high-quality tap water; yet the consumption of bottled water is widespread in the area and the fabrication of the plastic bottles and their transport by road means that a great amount of fossil fuel is burned, a contributor to global warming.

Students used a mobile application to create geo-located video content. Investigating the prospect of using mobile devices for guided video production, this application moderates the learning process by providing tasks to complete and video templates that structure the individual video content. The tasks were designed to be experienced by a student sequentially, progressing through the content in a way that is meant to aid in their understanding of the overall topic of water use and sustainability in their community. In completing the task, a student is guided through video creation, and is given the opportunity to communicate their own interpretation and understanding of a topic, ultimately producing individual scenes of a larger narrative. The students cooperate in groups of four to five, and conduct interviews with the public. They additionally participate in role-playing scenarios, taking the role of reporters, environmental activists or private water company owners. Through this process, students study the topic from multiple perspectives using media generation templates: private versus public water, greenhouse gas emission, overall climate change, the melting glaciers, as well as the cultural value of water for their local community. The application could be extended into an educational curriculum in schools academic calendar.

Memories are yet another aspect of a resilient cities. A city without a memory is like a dry city without a soul. Expressing and discovering memories in the city reveals the spirit of the historical, cultural and social values as well as identity. Memories sprout throughout the city and reflect emotional attachments to places. The Memory Traces

Project in collaboration with the Italian Consulate of Boston allows storytellers to describe their experiences and memories in a narrative approach. The potential of storytelling through new interactive media combines the digital environment with the physical urban environment. The project is an interactive collection of stories of Italians immigrants who live in Boston. 150 episodes of experiences and memories have been captured in an open source platform where geo-located video stories overlaid on a map of the city can be filtered by person, time, period or theme on the projects website http://locast.mit.edu/memorytraces/.

Conclusion

Better cities will emerge through participation of people, facilitating sociotechnological change through the convergence of industry, government and community for more sustainable outcomes.

In this chapter, some examples have been given through application of user generated and practice- based applications directed towards developing more resilient and sustainable cities. Here, new information and communication technologies and their applications represent key ingredients for future change in major urban sectors as well as cities and their built environments. Innovation is achievable through collaborating, engaging, participating and creating synergies.

Cities have evolved in different forms throughout the years depending on social, cultural, economic and environmental factors. Culture, global economy, climate, social issues have changed the places we live from skeleton skins to physiological cities. It is true that cities now have a nerve system, so it is important to explore new strategies, approaches and tools to involve residents and encourage them to participate in the decision making process, developing awareness related to the environment in which they are living, acting, producing and consuming.

However, a more holistic approach, benefitting from innovative uses of ICT platforms, can embrace shared media production and consumption practices fostering social connections, sparking citizen participation and improving the sense of community belonging at a range of scales - from citywide to the local neighborhoods.

It should be possible in the 21st century for everyone to participate in the process of sustainability through learning, civic engagement, and participatory urbanism so that cities can be livable and environmentally sustainable, as well as competitive, productive, socially inclusive, and resilient.

References Boyd, D. (2009). Taken Out of Context: American Teen Sociality in Networked Publics(Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Berkeley). Retrieved from[insert any DOI] Mitchell, J.M., Caselegno, F. (2008). Connected Sustainable Cities, USA, Mobile Experience Lab Publishing. Cambridge. Nelimarkka, M. (2008). The use of ubiquitous media in politics: how ubiquitous life effects into political life today and what might happen in the future in MindTrek '08 Proceedings of the 12th international conference on Entertainment and media in the ubiquitous era. New York. ACM Press Rheingold, H. (2002). Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution. Perseus Publishing. Shirky, C. (2008). Here comes everybody. Penguin Press. Federconsumatori. (2008). Acqua in bottiglia:laffare dellacqua 2008, Retrieved March 2011, http://www.federconsumatoripisa.it/29-09- 2008/acqua-bottiglia-laffare-dellacqua. IPCC, (2007). Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. World Wide Fund for Nature. Retrieved March 2011 http://assets.panda.org/downloads/glacierspaper.pdf

End Notes

1

Rio environmental mapping is part of The Social and Civic Media Sections global Digital Empowerment and Advocacy initiative (DEA). The local implementing partner Centro Desenvolvimento Apoio Programa Sade (CEDAPS) is a civil society organization that aims to develop the autonomy and capacity of impoverished communities by promoting equity, a better health and quality of life.

You might also like

- MIT Center For Future Civic Media: Engineering The Fifth EstateDocument8 pagesMIT Center For Future Civic Media: Engineering The Fifth EstateaptureincNo ratings yet

- Ascher HipertextoDocument6 pagesAscher HipertextoDaniela SilvaNo ratings yet

- The Academic Research Community PublicationDocument13 pagesThe Academic Research Community PublicationIEREKPRESSNo ratings yet

- ProjectsDocument112 pagesProjectsVenkatachalamNo ratings yet

- Acarter - Review #3 PaperDocument23 pagesAcarter - Review #3 PaperAthena CarterNo ratings yet

- Writing & Research: Keywords: Concept Description, Domain-Specific Research, Methodology, PrecedentsDocument13 pagesWriting & Research: Keywords: Concept Description, Domain-Specific Research, Methodology, PrecedentsBasakHazNo ratings yet

- Semantics-Powered Virtual Communities and Open Innovation For A Structured Deliberation ProcessDocument13 pagesSemantics-Powered Virtual Communities and Open Innovation For A Structured Deliberation ProcessdjentryNo ratings yet

- HICSS56 - SmartCities - Introduction v2Document2 pagesHICSS56 - SmartCities - Introduction v2AnnaNo ratings yet

- Digital Citizenship BehavioursDocument15 pagesDigital Citizenship BehavioursAli Abdulhassan AbbasNo ratings yet

- DAHLGREN, Peter - Media and The Public Sphere, P. 2906-2911Document5 pagesDAHLGREN, Peter - Media and The Public Sphere, P. 2906-2911Raquel SimõesNo ratings yet

- Hicss-Intro-Smart City - FinalDocument3 pagesHicss-Intro-Smart City - FinalAnnaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation ReflectionDocument7 pagesEvaluation ReflectionBasakHazNo ratings yet

- Introduction To HICSS Minitrack 2023Document2 pagesIntroduction To HICSS Minitrack 2023AnnaNo ratings yet

- (Carrasco-Saez Et Al, 2017) The New Pyramid of Needs For The Digital Citizen. A Transition Towards Smart Human CitiesDocument15 pages(Carrasco-Saez Et Al, 2017) The New Pyramid of Needs For The Digital Citizen. A Transition Towards Smart Human CitiesOscar Leonardo Aaron Arizpe VicencioNo ratings yet

- 13 - Planning For Protest - (Un) Planning For Protests, Madrid - Trienal de Arquitectura de Lisboa - PortugalDocument11 pages13 - Planning For Protest - (Un) Planning For Protests, Madrid - Trienal de Arquitectura de Lisboa - PortugalEcosistema Urbano100% (1)

- Chasing The Frontiers of Digital TechnologyDocument20 pagesChasing The Frontiers of Digital TechnologyThamara De Oliveira RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Potential and Limitations of Social Media Analysis for Urban StudiesDocument15 pagesPotential and Limitations of Social Media Analysis for Urban StudiesLuca SimeoneNo ratings yet

- Smart Cities: Transforming The 21st Century City Via The Creative Use of Technology (ARUP)Document32 pagesSmart Cities: Transforming The 21st Century City Via The Creative Use of Technology (ARUP)NextGobNo ratings yet

- Humphreys, L. (2010) - Mobile Social Networks and Urban Public Space. New Media Society, 12 (5), 763-778.Document16 pagesHumphreys, L. (2010) - Mobile Social Networks and Urban Public Space. New Media Society, 12 (5), 763-778.Daniel MartinezNo ratings yet

- This Is Hybrid - Texts - ArchitectureDocument38 pagesThis Is Hybrid - Texts - ArchitectureivicanikolicNo ratings yet

- Corp2023 115 231005 114049Document11 pagesCorp2023 115 231005 114049altimNo ratings yet

- Digital Futures and the City of Today: New Technologies and Physical SpacesFrom EverandDigital Futures and the City of Today: New Technologies and Physical SpacesNo ratings yet

- MIT Project Media LabDocument92 pagesMIT Project Media LabDarul QuthniNo ratings yet

- EN - Essay - Tech-Mediation: A Means To An EndDocument6 pagesEN - Essay - Tech-Mediation: A Means To An EndPatricia ValdésNo ratings yet

- Fireball d21 Paper-V3Document9 pagesFireball d21 Paper-V3hschaffersNo ratings yet

- Smart City Research As An Interdisciplinary Crossroads: A Challenge For Management and Organization StudiesDocument9 pagesSmart City Research As An Interdisciplinary Crossroads: A Challenge For Management and Organization StudiesjhoniNo ratings yet

- Douglas Schuler, Peter Day-Shaping The Network Society - The New Role of Civil Society in Cyberspace-The MIT Press (2004)Document444 pagesDouglas Schuler, Peter Day-Shaping The Network Society - The New Role of Civil Society in Cyberspace-The MIT Press (2004)ecristaldiNo ratings yet

- PPS Placemaking and The Future of CitiesDocument35 pagesPPS Placemaking and The Future of CitiesAndrysNo ratings yet

- ML ProjectsDocument54 pagesML ProjectsPriyabrata GhoraiNo ratings yet

- Building Human-Centered Systems in The Network SocietyDocument10 pagesBuilding Human-Centered Systems in The Network SocietyjmoutinhoNo ratings yet

- Urban Studio - Q&ADocument44 pagesUrban Studio - Q&AVaishali VasanNo ratings yet

- How Ideas and Ideals Shape Urban Media DesignDocument16 pagesHow Ideas and Ideals Shape Urban Media DesignsamfrovigattiNo ratings yet

- 2011 Productive Public Spaces Placemaking and The Future of CitiesDocument35 pages2011 Productive Public Spaces Placemaking and The Future of CitiesAstrid PetzoldNo ratings yet

- Mobilising Youth Towards Building Smart Cities Through Social Entrepreneurship: Case of Amman, JordanDocument13 pagesMobilising Youth Towards Building Smart Cities Through Social Entrepreneurship: Case of Amman, JordanIEREKPRESSNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 Urban GeographyDocument7 pagesLesson 2 Urban GeographyAlex Sanchez100% (1)

- Dawn of The Smart City?Document24 pagesDawn of The Smart City?The Wilson CenterNo ratings yet

- Life in A Smart CityDocument56 pagesLife in A Smart CityTatiane Rodrigues MateusNo ratings yet

- UrbanPamphleteer 1Document7 pagesUrbanPamphleteer 1Muhammad Munir AriffinNo ratings yet

- Welcome To The Participatory Age!Document12 pagesWelcome To The Participatory Age!Csaba madarászNo ratings yet

- ML ProjectsDocument54 pagesML ProjectsNikhil_Mohan_9738No ratings yet

- Tiedosta 042010Document2 pagesTiedosta 042010giluganoNo ratings yet

- MITMediaLab Projects Spring2017Document115 pagesMITMediaLab Projects Spring2017Ramiro FerrandoNo ratings yet

- Smart CityDocument12 pagesSmart CityElisha JadormeoNo ratings yet

- Urban Ai 1Document174 pagesUrban Ai 1Yue ZhaoNo ratings yet

- Digital Citizenship Final RevDocument6 pagesDigital Citizenship Final Revapi-549663723No ratings yet

- Internet of Things and Big Data Analytics For Smart and Connected CommunitiesDocument8 pagesInternet of Things and Big Data Analytics For Smart and Connected CommunitiesnhatvpNo ratings yet

- Pocket Parks 2Document40 pagesPocket Parks 2Marcelino AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Cyber Social-Networks and Social Movements Case-StudyDocument12 pagesCyber Social-Networks and Social Movements Case-StudyIJSER ( ISSN 2229-5518 )No ratings yet

- Las TNCT CN Sa Q4W3-4Document9 pagesLas TNCT CN Sa Q4W3-4Tristan Paul Pagalanan67% (3)

- What Future Cities Mean: Origins and InterpretationsDocument100 pagesWhat Future Cities Mean: Origins and InterpretationsGunaseelan Bhaskaran100% (1)

- 268 / Sarai Reader 2002: The Cities of Everyday LifeDocument7 pages268 / Sarai Reader 2002: The Cities of Everyday LifeMolly HankwitzNo ratings yet

- Plan 65365 Opinion Letter RezafarDocument3 pagesPlan 65365 Opinion Letter RezafarNaira SaeedNo ratings yet

- Usability in Government Systems: User Experience Design for Citizens and Public ServantsFrom EverandUsability in Government Systems: User Experience Design for Citizens and Public ServantsElizabeth BuieNo ratings yet

- ProjectsDocument91 pagesProjectsFelipe TorresNo ratings yet

- P2P FoundationDocument16 pagesP2P FoundationFlavio EscribanoNo ratings yet

- Citizen 2.0Document23 pagesCitizen 2.0potterhadiNo ratings yet

- Untangling Smart Cities: From Utopian Dreams to Innovation Systems for a Technology-Enabled Urban SustainabilityFrom EverandUntangling Smart Cities: From Utopian Dreams to Innovation Systems for a Technology-Enabled Urban SustainabilityNo ratings yet

- IAAC Bits 10 – Learning Cities: Collective Intelligence in Urban DesignFrom EverandIAAC Bits 10 – Learning Cities: Collective Intelligence in Urban DesignAreti MarkopoulouNo ratings yet

- Skill Point: Health Care DesignDocument30 pagesSkill Point: Health Care DesignpellinniNo ratings yet

- Smart Sustainability Book 12232011 HQDocument92 pagesSmart Sustainability Book 12232011 HQpellinniNo ratings yet

- Final Presentation-MEL 3dec2012Document63 pagesFinal Presentation-MEL 3dec2012pellinniNo ratings yet

- MOHE: Mobile Health For Moms, Kids, Adults and ElderlyDocument7 pagesMOHE: Mobile Health For Moms, Kids, Adults and ElderlypellinniNo ratings yet

- Service Design For Social Interaction: Mobile Technologies For A Healthier LifestyleDocument10 pagesService Design For Social Interaction: Mobile Technologies For A Healthier LifestylepellinniNo ratings yet

- FLIPR: Collaborative Media Sharing and The Urban LandscapeDocument2 pagesFLIPR: Collaborative Media Sharing and The Urban LandscapepellinniNo ratings yet

- Design Children's Products With Industries and Users.Document5 pagesDesign Children's Products With Industries and Users.pellinniNo ratings yet

- Locast H2flow: Creative Learning Tool For Participatory UrbanismDocument4 pagesLocast H2flow: Creative Learning Tool For Participatory UrbanismpellinniNo ratings yet

- Smile With SimpatiaDocument6 pagesSmile With SimpatiapellinniNo ratings yet

- Locast H2FlowDocument4 pagesLocast H2FlowpellinniNo ratings yet

- H2Flow - MobileLearningDocument8 pagesH2Flow - MobileLearningpellinniNo ratings yet

- Adult FrameDocument12 pagesAdult FramepellinniNo ratings yet

- Mobile Health PreventionDocument3 pagesMobile Health PreventionpellinniNo ratings yet

- Datasheet para ICDocument9 pagesDatasheet para ICepalexNo ratings yet

- Universiti Malaysia Sarawak Pre-TranscriptDocument2 pagesUniversiti Malaysia Sarawak Pre-Transcriptsalhin bin bolkeriNo ratings yet

- Real Estate Market Data Scraping and Analysis For Financial InvestmentsDocument67 pagesReal Estate Market Data Scraping and Analysis For Financial InvestmentsAgnaldo BenvenhoNo ratings yet

- Fujitsu Desktop Esprimo Q956: Data SheetDocument9 pagesFujitsu Desktop Esprimo Q956: Data SheetFederico SanchezNo ratings yet

- KMP Algorithm - Find Patterns in Linear TimeDocument4 pagesKMP Algorithm - Find Patterns in Linear TimeGrama SilviuNo ratings yet

- Archanadhaygude - 2yoe - SoftwaredeveloperDocument2 pagesArchanadhaygude - 2yoe - SoftwaredeveloperPRESALES C2LBIZNo ratings yet

- RRB CWE Sample Paper Officer Scale II IIIDocument5 pagesRRB CWE Sample Paper Officer Scale II IIINDTVNo ratings yet

- ! Assembly ItemsDocument60 pages! Assembly ItemsCostin AngelescuNo ratings yet

- 419925main - ITS-HB - 0040Document94 pages419925main - ITS-HB - 0040Murottal QuranNo ratings yet

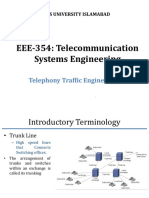

- EEE-354: Telecommunication Systems EngineeringDocument35 pagesEEE-354: Telecommunication Systems EngineeringBilal HabibNo ratings yet

- Avaya Interaction Center Release 7.3 Database Designer Application ReferenceDocument252 pagesAvaya Interaction Center Release 7.3 Database Designer Application ReferenceRodrigo MahonNo ratings yet

- ASTM STP1385 Durability 2000 Accelerated and Outdoor Weathering TestingDocument186 pagesASTM STP1385 Durability 2000 Accelerated and Outdoor Weathering TestingKYAW SOENo ratings yet

- Computational MethodsDocument2 pagesComputational MethodsEfag FikaduNo ratings yet

- 01 PTP Survey ProcedureDocument3 pages01 PTP Survey ProcedureAnonymous 1XnVQmNo ratings yet

- Activity Exemplar Product BacklogDocument4 pagesActivity Exemplar Product BacklogHello Kitty100% (2)

- 15A05606 Artifical Intelligence PDFDocument1 page15A05606 Artifical Intelligence PDFAnand Virat100% (1)

- History of The InternetDocument3 pagesHistory of The InternetAngelly V Velasco100% (1)

- List of AMD Accelerated Processing Units - WikipediaDocument12 pagesList of AMD Accelerated Processing Units - WikipediaMD Showeb Arif SiddiquieNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument214 pagesPDFKumari YehwaNo ratings yet

- CPPS LAB 15 SolutionsDocument11 pagesCPPS LAB 15 SolutionsJoyceNo ratings yet

- Python Fundamentals SheetDocument29 pagesPython Fundamentals Sheetwp1barabaNo ratings yet

- 7 Coursebook ScienceDocument196 pages7 Coursebook SciencegordonNo ratings yet

- Introduction To SageERPX31Document33 pagesIntroduction To SageERPX31Usman Khan100% (1)

- Pre-Calculus 11 WorkbookDocument44 pagesPre-Calculus 11 Workbooklogicalbase3498No ratings yet

- N4 Xtend Training v3Document3 pagesN4 Xtend Training v3Talha RiazNo ratings yet

- Miran Sapphire 205B ManualDocument216 pagesMiran Sapphire 205B ManualrobertsmithingNo ratings yet

- Signal Generator With Arduino Using DDS and Pico - Hackster - IoDocument9 pagesSignal Generator With Arduino Using DDS and Pico - Hackster - IoAhmed Abdel AzizNo ratings yet

- Accessing VDIs and logging into NetScaler GatewayDocument7 pagesAccessing VDIs and logging into NetScaler GatewayMohsin ModiNo ratings yet

- IT Risk Assessment QuestionnaireDocument7 pagesIT Risk Assessment QuestionnaireRodney LabayNo ratings yet

- Attendance Management System Using Barco PDFDocument7 pagesAttendance Management System Using Barco PDFJohnrich GarciaNo ratings yet