Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Arabic Origins of "Body Part Terms" in English and European Languages: A Lexical Root Theory Approach

Uploaded by

lazyaliciaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Arabic Origins of "Body Part Terms" in English and European Languages: A Lexical Root Theory Approach

Uploaded by

lazyaliciaCopyright:

Available Formats

Available online at http://www.bretj.

com

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT APPLIED LINGUISTICS AND ENGLISH LITERATURE

RESEARCH ARTICLE

International Journal of Current Applied Linguistics and English Literature- Vol.1, Issue, 2, pp. 3-14, March, 2013

THE ARABIC ORIGINS OF "BODY PART TERMS" IN ENGLISH AND EUROPEAN LANGUAGES: A LEXICAL ROOT THEORY APPROACH Zaidan Ali Jassem

Department of English Language and Translation, Qassim University, P.O.Box 6611, Buraidah, KSA ART IC LE

Article History: Received 10th, February,2013 Received in revised form 26th, February,2013 Accepted 10th, March, 2013 Published online 28th, March,2013 Key words:

INF O

ABSTR ACT

This paper examines the Arabic cognates and/or origins of body part terms in English, German, French, Latin, and Greek from a lexical root theory perspective. The data consists of well over 200 terms such as face, nose, eye, hand, heart, stomach, gastric, leg, and so on. The results show that all such words are true cognates in Arabic and such languages, with the same or similar forms and meanings. The different forms amongst such words are shown to be due to natural and plausible causes of linguistic (phonetic, morphological and semantic) change. For example, English nose and German Nase come from Arabic anf, unoof (pl.) 'nose' where /f/ became /s/. Similarly, English gastro/gastric (Greek graster 'stomach') and Old English crse 'cress' derive from Arabic karsh(at) 'stomach' via different routes like reordering and turning /k & sh/ into /g & s/. This entails that Arabic, English and so on belong not only to the same family but also to the same language, contrary to traditional Comparative Method claims. Due to their phonetic complexity, huge lexical variety and multiplicity, Arabic words are the original source from which they emanated. This demonstrates the adequacy of the lexical root theory according to which Arabic, English, German, French, Latin, and Greek are dialects of the same language with the first being the origin. Copy Right, IJCALEL, 2013, Academic Journals. All rights reserved.

Body part terms, Arabic, English, German, French, Latin, Greek, historical linguistics, lexical root theory

INTRODUCTION

The lexical root theory has been proposed by Jassem (2012a-f, 2013a-g) to reject the claims of the comparative 'historical linguistics' method that Arabic, on the one hand, and English, German, French, and all (Indo-)European languages in general, on the other, belong to different language families (Bergs and Brinton 2012; Algeo 2010; Crystal 2010: 302; Campbell 2006: 190-191; Crowley 1997: 22-25, 110-111; Pyles and Algeo 1993: 61-94). Instead, it firmly established the very close genetic relationship between Arabic and such languages for three main reasons: namely, (a) geographical continuity and/or proximity between their homelands, (b) persistent cultural interaction and similarity between their peoples over the ages, and, above all, (c) linguistic similarity between Arabic and such languages (see Jassem 2013b for further detail). In his papers, Jassem (2012a-f, 2013a-g) covered the three main areas of language study: phonetics (phonology), morphology (grammar), and semantics (lexis). On the *Corresponding author: Tel; +966-6- 325 2332 Email: zajassems@gmail.com

lexical level, Jassem (2012a: 225-41) was his first study, which showed that numeral words from one to trillion in Arabic, English, German, French, Latin, Greek and Sanskrit share the same or similar forms and meanings in general, forming true cognates with Arabic as their end origin. For example, three (third, thirty, trio, tri, tertiary, trinity, Trinitarian) derives from a 'reduced' Arabic thalaath (talaat in Damascus Arabic (Jassem 1993, 1994ab)) 'three' through changing /th & l/ to /t & r/ each. There came strong support and decisive linguistic evidence from all subsequent studies. Jassem (2012b: 59-71) traced the Arabic origins of common contextualized biblical or religious terms such as Hallelujah, Christianity, Judaism, worship, bead, and so on. For instance, hallelujah resulted from a reversal and reduction of the Arabic phrase la ilaha illa Allah '(There's) no god but Allah (God)'. That is, Halle is Allah in reverse, lu and la 'not' (pronounced lo also) are the same, jah is a shortening of both ilaaha 'god' and illa 'except' which sound almost the same. Jassem (2013d: 126-51) described the Arabic cognates and origins of

International Journal of Current Applied Linguistics and English Literature- Vol.1, Issue, 2, pp. 3, 14, 2013

English, German, and French water and sea terms like water, hydro, aqua, sea, ocean, ship, navy, fish. Jassem (2013e: 631-51) traced back the Arabic origins of air and fire terms in English and such languages. Jassem (2013f) described the Arabic origins of celestial (e.g., sky, star, sun) and terrestrial (e.g., earth, mountain, hill) terms in English and such languages. Finally, Jassem (2013g) depicted the Arabic origins of animal terms (e.g., cow, sheep, horse, cat, lion) in English and such languages. On the morphological plane, three papers have appeared. Jassem (2012f) showed that inflectional 'plural and gender' markers as in oxen, girls, Paula, Charlotte formed true cognates in all such languages. Similarly, Jassem (2013a: 48-72) demonstrated the Arabic origins of English, German, and French derivational morphemes as in activity, activate, determine, whiten, whose identical Arabic cognates are ta (e.g., salaamat(i) 'safety', takallam 'talk') and an (e.g., wardan 'bloom'). Finally, Jassem (2013b: 234-48) dealt with the Arabic origins of negative particles and words like in-/no, -less, and -mal in English, French and so on. On the grammatical axis, three papers have been conducted so far. Jassem (2012c: 83-103) found that personal pronouns in Arabic, English, German, French, Latin and Greek form true cognates, which descend from Arabic directly. For example, you (ge in Old English; Sie in German) all come from Arabic iaka 'you' where /k/ changed to /g (& s)/ and then to /y/; Old English thine derives from Arabic anta 'you' via reversal and the change of /t/ to /th/ whereas thou and thee, French tu, and German du come from the affixed form of the same Arabic pronoun -ta 'you'. Jassem (2012d: 323-59) examined determiners such as the, this, a/an, both, some, all in English, German, French, and Latin which were all found to have identical Arabic cognates. For instance, the/this derive from Arabic tha/thih 'this' where /h/ became /s/. Finally, Jassem (2012e: 185-96) established the Arabic origins of verb to be forms in all such languages. For example, is/was (Old English wesan 'be'; German sein; French etre, es, suis) descend from Arabic kawana (kaana) 'be' where /k/ became /s/. At the phonological level, Jassem (2013c) outlined the English, German, French, Latin, and Greek cognates of Arabic back consonants: i.e., the glottals, pharyngeals, uvulars, and velars. For example, church (kirk, ecclesiastical) all come from Arabic kanees(at) where /k & n/ became /ch & r (l)/ each. In all the papers, the phonetic analysis is central, of course. In this paper, the lexical root theory will be used as a theoretical framework (2.2.1 below). It has five sections: an introduction, research methods, results, a discussion, and a conclusion.

the author's knowledge of their frequency and use and English thesauri. They have been arranged alphabetically for quick reference together with brief linguistic notes in (3.) below. All etymological references to English below are for Harper (2012) and to Arabic for Altha3aalibi (2011: Chs. 14-15), Ibn Seedah (1996: Chs. 1-2 & 8), Ibn Khaalawaih (2013), and Ibn Manzoor (2013). The data is transcribed by using normal spelling. For unique Arabic sounds, however, certain symbols were used- viz., /2 & 3/ for the voiceless and voiced pharyngeal fricatives respectively, /kh & gh/ for the voiceless and voiced velar fricatives each, capital letters for the emphatic counterparts of plain consonants /t, d, dh, & s/, and /'/ for the glottal stop (Jassem 2013c). Data Analysis Theoretical Framework: The Lexical Root Theory As in all the above studies, the lexical root theory will be used as the theoretical framework for the investigation of the Arabic genetic origins and descent of body part terms in English, German, French, Latin, and Greek. It is so called because of employing the lexical (consonantal) root in examining genetic relationships between words like the derivation of overwritten from write (or simply wrt). The main reason for that is because the consonantal root carries and determines the basic meaning of the word regardless of its affixation such as overwrite, writing. Historically speaking, classical Arabic dictionaries (e.g., Ibn Manzoor 1974, 2013) used consonantal roots in listing lexical entries, a practice first founded by Alkhaleel (Jassem 2012e). The structure of the lexical root theory is simple, which comprises a theoretical construct, hypothesis or principle and five practical procedures of analysis. The principle states that Arabic and English as well as the so-called Indo-European languages are not only genetically related to but also are directly descended from one language, which may be Arabic in the end. In fact, it claims in its strongest version that they are all dialects of the same language, whose differences are due to natural and plausible causes of linguistic change. The applied procedures of analysis are (i) methodological, (ii) lexicological, (iii) linguistic, (iv) relational, and (v) comparative/historical. As all have been reasonably described in the above studies (Jassem 2012a-f, 2013a-g), a brief summary will suffice here. To start with, the methodological procedure concerns data collection, selection, and statistical analysis. Apart from loan words, all language words, affixes, and phonemes are amenable to investigation, and not only the core vocabulary as is the common practice in the field (Crystal 2010; Pyles and Algeo 1993: 76-77; Crowley 1997: 88-90, 175-178). However, data selection is practically inevitable for which the most appropriate way would be to use semantic fields such as the present and the above topics. Cumulative evidence from such findings will aid in formulating rules and laws of language change at a later stage (cf. Jassem 2012f, 2013a-g). The statistical analysis employs the percentage formula (see 2.2 below).

RESEARCH METHODS

The Data The data consists of well over 200 body part words such as face, nose, mouth, eye, stomach, intestine, heart, hand, leg, hair, and so on. They have been selected on the basis of

4|P a ge

International Journal of Current Applied Linguistics and English Literature- Vol.1, Issue, 2, pp. 3, 14, 2013

Secondly, the lexicological procedure forms the initial step in the analysis. Words are analyzed by (i) removing affixes (e.g., overwritten write), (ii) using primarily consonantal roots (e.g., write wrt), and (iii) search for correspondence in meaning on the basis of word etymologies and origins as a guide (e.g., Harper 2012), to be used with discretion, though. Thirdly, the linguistic procedure tackles the analysis of the phonetic, morphological, grammatical and semantic structures and differences between words. The phonetic analysis examines sound changes within and across categories. In particular, consonants may change their place and manner of articulation as well as voicing. At the level of place, bilabial consonants labio-dental dental alveolar palatal velar uvular pharyngeal glottal (where signals change in both directions); at the level of manner, stops fricatives affricates nasals laterals approximants; and at the level of voice, voiced consonants voiceless. Similarly, vowels may change as well. The three basic long Arabic vowels /a: (aa), i: (ee), & u: (oo)/ (and their short versions besides the two diphthongs /ai (ay)/ and /au (aw)/ which are a kind of /i:/ and /u:/ respectively), may change according to (i) tongue part (e.g., front centre back), (ii) tongue height (e.g., high mid low), (iii) length (e.g., long short), and (iv) lip shape (e.g., round unround). These have additional allophones or variants which do not change meaning (see Jassem 2013h). Although English has a larger number of about 20 vowels, which vary from accent to accent (Roach 2009; CelceMurcia et al 2010), they can still be treated within this framework. Furthermore, vowels are marginal in significance which may be totally ignored because the limited nature of the changes do not affect the final semantic outcome at all. In fact, the functions of vowels are phonetic like linking consonants to each other in speech and grammatical such as indicating tense, word class, and number (e.g., sing, sang, sung, song; man/men). Sound changes result in processes like assimilation, dissimilation, deletion, merger, insertion, split, syllable loss, resyllabification, consonant cluster reduction or creation and so on. In addition, sound change may operate in a multi-directional, cyclic, and lexically-diffuse or irregular manner (see 4. below). The criterion in all the changes is naturalness and plausibility; for example, the change from /k/ (e.g., kirk, ecclesiastic), a voiceless velar stop, to /ch/ (e.g., church), a voiceless palatal affricate, is more natural than that to /s/, a voiceless alveolar fricative, as the first two are closer by place and manner (Jassem 2012b); the last is plausible, though (Jassem 2013c). As to the morphological and grammatical analyses, there exists some overlap. The former examines the inflectional and derivational aspects of words in general (Jassem 2012f, 2013a-b); the latter handles grammatical classes, categories, and functions like pronouns, nouns, verbs, and case (Jassem 2012c-d). Since their influence on the basic meaning of the lexical root is marginal, they may be ignored altogether.

Concerning the semantic analysis, meaning relationships between words are examined, including lexical stability, multiplicity, convergence, divergence, shift, split, change, and variability. Stability means that word meanings have remained constant. Multiplicity denotes that words might have two or more meanings. Convergence means two or more formally and semantically similar Arabic words might have yielded the same cognate in English. Divergence signals that words became opposites or antonyms of one another. Shift indicates that words switched their sense within the same field. Lexical split means a word led to two different cognates. Change means a new meaning developed. Variability signals the presence of two or more variants for the same word. Fourthly, the relational procedure accounts for the relationship between form and meaning from three perspectives: formal and semantic similarity (e.g., three, third, tertiary and Arabic thalath 'three' (Damascus Arabic talaat (see Jassem 2012a)), formal similarity and semantic difference (e.g., ship and sheep (see Jassem 2012b), and formal difference and semantic similarity (e.g., quarter, quadrant, cadre and Arabic qeeraaT '1/4' (Jassem 2012a)). Finally, the comparative historical analysis compares every word in English in particular and German, French, Greek, and Latin in general with its Arabic counterpart phonetically, morphologically, and semantically on the basis of its history and development in English (e.g., Harper 2012; Pyles and Algeo 1993) and Arabic (e.g., Ibn Manzour 2013; Altha3aalibi 2011; Ibn Seedah 1996) besides the author's knowledge of both Arabic as a first language and English as a second language. Statistical Analysis The statistical analysis employs the percentage formula, obtained by dividing the number of cognates over the total number of investigated words multiplied by a 100. For example, suppose the total number of investigated words is 10, of which 9 are true cognates. Calculating the percentage of cognates is obtained thus: 9/10 = 0.9 X 100 = 90%. Finally, the results are checked against Cowley's (1997: 173, 182) formula to determine whether such words belong to the same language or to languages of the same family (for a survey, see Jassem 2012a-b).

RESULTS

Abdomen from Arabic baTn, abTun/buToon (pl.) 'abdomen'; /T/ became /d/ and /m/ split from /n/. Alveolus (alveolar) from Arabic laththa(t) 'alveolus, tooth gums'; /th/ mutated into /v/. Anemia from Arabic damm 'blood'; /d/ turned into /n/. Ankle from Arabic kaa2il, ak2al 'ankle' via reordering, /2/-loss and /n/-insertion. Antenna (audition, auditory, auditorium, audience) from Arabic udhun, uhthain(at) (dim.) 'ear'; /dh/ changed to /t/ or /d/. Anus (anal) from Arabic 3aana(t) 'anus' via /3/-loss and /t/-mutation into /s/ or hann, haneen 'vagina' via lexical shift and /h/-loss (cf. annum, annual from Arabic 3aam 'year' via /3/-loss and turning /m/ into /n/).

5|P a ge

International Journal of Current Applied Linguistics and English Literature- Vol.1, Issue, 2, pp. 3, 14, 2013

Arm (arms, armistice, army, armada; omen) from Arabic yameen, aymaan (pl.) 'right hand' via reordering and turning /n/ into /r/ (cf. rum2 'arrow' via /2/-loss; raami, rumaat (pl.) 'thrower, soldier, army' via reordering). Arse from Arabic sharj 'arse' through reordering and /sh & j/-merger into /s/ (cf. Eros below). Artery from Arabic wareed 'blood vessel' in which /d/ became /t/ or wateen 'artery' via reordering and turning /n/ into /r/. Ass from Arabic 2ush, 2ushoosh (pl.) 'ass, back hole' where /2 & sh/ merged into /s/, 3uSS 'ass' where /3 & S/ merged into /s/, or ja2sh 'donkey' via merging /j, 2, & sh/ into /s/ (Jassem 2013g). Audience (audio, audition, auditory, auditorium, antenna) from Arabic udhun 'ear, hearing' where /dh/ changed to /d/. Audio (audition, auditory, auditorium, antenna, audience, audio-lingual) from Arabic udhun, uhthain(at) (dim.) 'ear' where /dh & n/ merged into /d/; for lingual, see below. Auricle (aura + -cle 'little ear') from a combination of Arabic 3air 'ear' via /3/-loss and qal(eel) 'little' where /q/ became /k/ (see ear below). Back (aback) from Arabic 3aqib 'back, after' via reversal and /3/-loss. Banana (pen) from Arabic loan banaan 'fingers'. Beard (barber) (Latin barba, German Bart, and Lithuanian barzda) from Arabic shaarib 'moustache' via reversal and turning /sh/ into /d/ or merger into /b/ in Latin. Belly (Old English b(e/y)lg 'leather bag, purse, bellows; to swell') from Arabic qirba(t), qirab (pl.) 'leather bag' via reversal and turning /q & r/ into /g (y) & l/ each (cf. kabeer 'big, swell' via reordering and turning /k & r/ into /g & l/). Bladder 'blister, pimple in Old English' from Arabic buthoor 'blisters' via lexical shift, turning /th/ into /d/, and /l/-insertion, baDhar 'clitoris' via lexical shift, turning /Dh/ into /d/, and /l/-insertion, or dubur 'anus, back' via lexical shift, reordering, and /l/-insertion or split from /r/ (see gall bladder below). Blade (shoulder blade) from Arabic balaaTa(at) 'flat surface' via lexical shift and turning /T/ into /d/. Blood (bleed) from Arabic baTTa 'of wounds and blisters, to burst' where /T/ became /d/ and /l/ was inserted; damm 'blood' via reversal, changing /m/ to /b/, and /l/-insertion; or Tilaa' 'victim's blood' through reversal, turning /T/ into /d/, and /b/-insertion. Body (Old English bodig 'chest, trunk'; Old High German botah) from Arabic bat3 'long-necked and strong-jointed (man)' or badgh 'fat, full-bodied' where /t & 3 (gh)/ turned into /d & g/; baD3(at), baaDi3 'piece (of meat); group of sheep; full-bodied (man)' where /D & 3/ became /d & g/; baajid, bajad (pl.) 'person/resident, group of people' via reordering and turning /j/ into /g/; or badan(at) 'body' in which /n/ merged into /b/ (cf. qaDeeb 'rod, something held' through lexical shift, reversal and changing /q & D/ to /g (y) & d/; qatab 'irritable, narrow-minded man' via reversal and turning /q & t/ into /g () & d/). Bone from Arabic naab 'tooth' via reversal and lexical shift or banaan 'finger, bone' via lexical shift (cf. combine from Arabic bana 'build').

Bottom from Arabic baTn, buToon (pl.) 'belly'; /T & n/ changed to /t & m/ each. Bowel from Arabic lubb 'inner part; heart' via reversal and lexical shift; mib3ar (ba3ar) 'intestine (foul)' via /m & b/merger and turning /3 & r/ into /w & l/; or 2abl, 2ibaal (pl.) 'cable' via /2/-loss and lexical shift. Brain (Old English brgen; Greek brekhmos 'top of the head') from Arabic jabeen 'forehead' via lexical shift, turning /j/ into /g/, and /r/-insertion; nabbaa3a(t) 'of babies, soft part of skull' via reordering and turning /3 & n/ into /g & r/; burj 'tower, top' via lexical shift and turning /j/ into /g/ (cf. qanbar 'top (bird's head feather)' and ghaarib 'top of all; shoulder' via lexical shift, reordering and turning /q & gh/ into /g/.) Breast from Arabic bark '(mid) breast' where /k/ split into /s & t/ (cf. buhrat 'mid body' via reordering and turning /h/ into /s/). Breath (breathe) from Arabic bard 'cold air' in which /d/ became /t/ (Jassem 2013f). Bronchitis (branch) via Greek bronkhos 'windpipe, throat' from Arabic khanaab 'nose edge; big nose' via lexical shift, reordering, turning /kh/ into /ch/, and /r/-insertion (cf. 3arbash 'to branch out, climb' via reordering and /3/mutation into /n/). Brow from Arabic wabar 'eye hair' through reversal and lexical shift (cf. barra, birrawi (n) 'look stealthily'). Cadavre from Arabic jeefat 'dead body' via reordering and turning /j & t/ into /k & d/ besides /r/-insertion or juththa(t) 'body' via reordering and turning /j, th, & t/ into /k, d, & v/. Cage from Arabic qafaS 'cage' in which /q/ became /k/ while /f & S/ merged into /j/ or jaush 'breast' where /j & sh/ became /k & j/. Calf from Arabic katf 'shoulder' via lexical shift and turning /t/ into /l/ or kaff 'hand palm' via lexical shift and /l/-insertion (cf. Jassem 2013g). Canine from Arabic sinn, sunoon/asnaan (pl.) 'tooth'; /s/ changed to /k/. Capita (capital) 'head' from Arabic jabhat 'forehead' via lexical shift and turning /j, h, & d/ into /k, , & t/. Cardiac (cardiology, cordial; heart) from Arabic Sadr, Sudoor (pl.) 'breast, heart' via reordering and turning /S/ into /k/ (cf. heart below). Cartilage from Arabic gharDoof, ghaDroof 'cartilage' where /gh & D/ became /k & t/ whereas /l/ split from /r/ or 3aDalat 'muscle' via lexical shift, turning /3/ into /k/, and /r/-insertion. Cavity (excavate, cave) from Arabic kahf 'cave' via /h & f/- merger into /v/ or jauf 'cavity, hollow inside' where /j/ turned into /k/. Cell via Latin cella 'small room for a monk/nun' from Arabic khalwa(t), khala 'small room for worship; void'; /kh/ became /s/. Cheek from Arabic shiq 'section, side' where /q/ became /k/ or khad 'cheek' in which /kh/ split into /ch & k/ into which /d/ merged (cf. Saf2a(t) 'side' via /S & f/-merger into /ch/ and /2/-mutation into /k/.

6|P a ge

International Journal of Current Applied Linguistics and English Literature- Vol.1, Issue, 2, pp. 3, 14, 2013

Chest from Arabic qaSS(at) 'chest'; /q & S/ turned into /ch & s/ (cf. jasad 'body' where /j & d/ turned into /s & t/ besides lexical shift). Chin from Arabic dhaqn, dhuqoon (pl.) 'chin'; /dh & q/ merged into /ch/. Clitoris (Greek kleitoris diminutive of kleis 'key; shutting') from Arabic qifl 'key' via reordering and turning /q & f/ into /k & s (t)/ or shafrat, shifaar 'vaginal edge' where /sh, f, & t/ became /k, t, & s/ besides /l/-insertion. Coccyx from Arabic 3uS3uS 'coccyx'; /3 & S/ became /k & s/ Collar from Arabic na2r 'neck (slaughter line)' via reordering and turning /2 & n/ into /k & l/ or nuqra(t) 'hole' via reordering and turning /n/ into /l/ besides lexical shift. Colon from Arabic khurraan 'large intestine, arse' where /kh & r/ changed to /k & l/. Cord (spinal cord) from Arabic shareeT 'cord, string'; /sh & T/ passed into /k & d/ each (cf. accord (according to) from Arabic sharT 'condition' via lexical shift). Cornea (corner) from Arabic qarnia(t) 'cornea, corner'; /q/ became /k/. Corpus (corpora, corporal, corporeal, corps, incorporate) 'body' from Arabic bashar 'human body' via lexical shift, reordering, and /sh/-mutation into /k/ or jiraab (qiraab) 'bag, purse' via lexical shift and /j & q/-mutation into /k/. Corps 'dead body' from Arabic qabr 'grave' via lexical shift, reordering, and /q/-mutation into /k/. Cranium (cranial) from Arabic qarn 'horn' via lexical shift (cf. horn, crown, coronation, crane in Jassem (2013c, 2013g)). Cubic (bone, cube) from Arabic ka3b 'cube' via /3/-loss. Cuff from Arabic kaff 'hand, palm' via lexical shift. Cunt from Arabic 3aanat 'anus, vagina' where /3/ became /k/ or khitaan 'vagina or penis; clit cutting' via reordering and turning /kh/ into /k/. Cyst (sack) (Greek kystis and Latin cysticus 'bag, bladder') from Arabic kees(at) 'bag' where /k/ changed to /s/. Cyto- 'cell, cover in Latin' via Greek kytos 'a receptacle, basket' from Arabic ghiTaa 'cover'; /gh & T/ turned into /s & t/. Dental (dentist) from Arabic thania(t) 'tooth'; /th/ became /d/ (cf. tooth below). Dermis (dermatology) from Arabic adeem, adamat 'skin' where /t/ changed to /s/ from which /r/ split or was inserted. Diaphragm 'partition' (Greek dia 'across' and phragma 'fence') from Arabic furqaan, tafreeq 'division' where /q & n/ became /g & m/. Dick from Arabic dhakar 'penis, male' where /dh & r/ became /k & / (cf. adaaf 'penis' where /f/ changed to /k/). Digit (digital, digitalization; decameter; decimal) via Latin digitus 'finger' from Arabic daja(t) '(food-carrying) fingers' (cf. Jassem (2012a)). Dorsum (dorsal, endorse, endorsement) from Arabic Dhahr 'dorsum, back' through reordering and turning /Dh & h/ into /d & s/.

Duodenum from a combination of two and ten, which have already been resolved in Jassem (2012a). Ear (hear; auricle) from Arabic 3air '(highest part of) ear' via /3/-loss. Egg from Arabic kaika(t) 'egg' where /k/ became /g/ or qai'at 'egg skin' where /q/ changed to /g/. Ejaculate from Arabic za'jal 'male ostrich's semen' via lexical shift and turning /z & j/ into /j & k/; shakhal 'drip from sieve or cloth' where /sh & kh/ became /j & k/ each; or shakhkha 'piss' where /sh & kh/ became /j & k/ each besides /l/-insertion). Elbow from Arabic alboo3 'elbow' via /3/-deletion and lexical shift. Embrace (brace) from Arabic raqaba(t) 'neck, roundness' via reversal, /q/-mutation into /s/, and lexical shift. Envy (envious) from Arabic 3ain 'eye' via reordering, /3/mutation into /n/ and lexical shift (see eye below) or nafs 'self, envy' where /f & s/ merged into /v/). Eros (erotic, Erasmus, eratus) 'love in Geek' from Arabic 3aroos, 3irsaan 'bride(groom)' or 3arS 'pimp' via /3/deletion (cf. air 'penis' and 2ir2 'vagina' via lexical shift, /2/-loss and mutation into /s/; rahaz 'sexual act movement' via /h/-loss; arse above). Esophagus 'what carries and eats in Greek' from Arabic shaal 'carry' where /sh/ became /s/ while /l/ merged into /o/ and shaba3 'eat-up' via reordering and turning /sh & 3/ into /s & g/ (cf. Sifaaq 'thin, flat side meat' where /S & q/ became /f & g/). Eye (German Auge) from Arabic 2ijaj 'eye cavity, bone' via lexical shift, /2/-loss, and turning /j/ into /y/ or 2adaqa(t) 'eye centre' where /2, d, & q/ merged into /g (y)/ (cf. envy (envious) above and ocular below). Face from Arabic wajh 'face' (wish in Syrian Aleppo Arabic) in which /w/ turned into /f/ while /j & h/ merged into /s/ or faah 'mouth' via lexical shift and turning /h/ into /s (see vis--vis below). Fat from Arabic zait 'oil' in which /z/ changed to /f/ or zubda(t) 'butter' where /z & b/ merged into /f/ and /d/ became /t/. Female (feminine) via French femme from Latin femina 'woman' and femella 'young girl (dim.)' from Arabic untha, mu'annath (adj.) 'female, woman' via reordering and turning /th/ into /f/. Finger from Arabic khinSar 'ring finger' or banSar 'little finger' where /kh (b) & S/ turned into /f & g/ each or barajim 'finger parts/knots' via reordering and changing /b & m/ to /f & n/. Flesh from Arabic jild 'skin' via reversal, lexical shift and turning /j & d/ into /sh & f/ respectively or la2m 'flesh' via reordering and turning /2 & m/ into /sh & f/ each (cf. sha2m 'fat' via reversal, lexical shift, /2 & sh/-merger, /m/mutation into /f/, and /l/-insertion/). Foot (pedal, pedestrian; German Fuss) from Arabic qadam 'foot' via reversal, merging /q & d/ into /t/, and turning /m/ into /f/. Fore(head) from Arabic ghurra(t) 'fore' in which /gh/ became /f/. Gall (bladder) from Arabic ghill 'hate, venom' where /gh/ became /g/ or Safra 'yellow' where /S & f/ merged into /g/ and /r/ became /l/; for bladder, see above.

7|P a ge

International Journal of Current Applied Linguistics and English Literature- Vol.1, Issue, 2, pp. 3, 14, 2013

Gastric (Greek g(r)aster 'stomach', Old English crce) from Arabic karshat 'stomach' via reordering and turning /k & sh/ into /g & s/. Gingivitis (gingival) 'Latin tooth gums' from a combination of Arabic sin, asnaan (pl.) 'tooth' via lexical shift and turning /s/ into /g/ and 2aaffa(t) 'edge' where /2/ became /g/. Gland from Arabic 3anqood 'bunch' via /3 & q/-merger into /g/ and /l/-insertion (cf. ghudda(t) 'gland' via turning /gh/ into /g/ and /l & n/-insertion). Glottis (Latin glotta and Greek glossa 'tongue') from Arabic asalat 'tongue edge' where /s/ became /g/, lahjat 'tongue edge' via reordering, merging /h & j/ into /g/, or turning them into /s & g/, or falaka(t) 'tongue-base flesh protrusion' via reordering and turning /k & f/ into /g & t/. Goitre (Latin guttur, guttural 'throat') from Arabic jawzat 'throat, larynx' where /j & z/ merged into /g/ besides /r/insertion, zawr 'throat' where /z/ split into /g & t/, reeq(at) 'throat' via reversal and /q/-mutation into /g/, or daraq(iat) 'thyroid' via reordering and lexical shift. Gorge (Latin gorges 'throat') from Arabic gharghar(at) 'top windpipe' where /gh/ became /g/ or sharq 'split' where /sh & q/ changed to /g & j/. Groin (Old English grynde 'ground depression') from Arabic nuqra(t) 'ground hole' via reordering and turning /q & t/ into /g & d/ each. Gull (gullet) (Latin gula 'throat') from Arabic 2alq 'throat' via reversal and /2 & q/-merger into /g/. Gyne (gynecology, queen) from Arabic nisaa 'women' via reversal and /s/-mutation into /g (q)/. Hair from Arabic sha3r 'hair' where /sh & 3/ merged into /h/. Hand (yard) from Arabic yad ('eed), yadain (pl.) 'hand' in which /'/ changed to /h/, zind, zunood (pl.) 'arm, hand; rod' in which /z/ became /h/, or dhiraa3, dhir3aan (pl.) 'arm' via reversal and turning /r & 3/ into /n & h/. Head (Old English heafod 'top of head' and German Haupt) from Arabic wajh 'face, head', wajeeh 'head, chief, lord' where /w & h/ merged into /h/ while /j/ turned into /d/. Hear (ear) from Arabic 3air, a3aar 'ear, hear'; /3/ became /h/ (cf. ear above). Heart (cardiac, cardiology; cordial) (Old English hearte 'heart, breast, soul, mind', German Herz, Russian serdce 'breast', Lithuanian irdis 'heart') from Arabic Sadr, Sudoor (pl.) 'heart, breast' in which /S & d/ turned into /h & d/ respectively. Hemoglobin from a combination of Arabic damm 'blood' where /d/ changed to /h/ and qalb, quloob (pl.) 'heart, ball' where /q/ turned into /g/ (cf. globe from Arabic qilaab 'land, earth'). Hepatitis from Arabic kabd 'liver' in which /k & d/ turned into /h & t/ respectively. Hide from Arabic jild 'skin' where /j & l/ became /h & /. Hip from Arabic 2ajaba(t) 'hip head' via lexical shift and merging /2 & j/ into /h/ or qabb 'hip bone' where /q/ became /h/. Horny from Arabic haram, mahroom, minharim 'horny, aroused' where /m/ became /n/ or haneen 'vagina' where /n/ changed to /r/ (cf. hornet from Arabic na2lat 'honey bee' via reordering and turning /2 & l/ into /h & r/ each (Jassem 2013g).

Hug from Arabic 3inaaq 'neck, hugging' via lexical shift, /3/-mutation into /h/, and /n/-loss. Ilium from Arabic ilia(t) 'ilium, bottom'. Image (imagination) from Arabic seema 'image, mark' via reversal and turning /s/ into /j/ or from wajh 'face' via lexical shift, turning /w/ into /m/, and merging /h/ into /j/. Inspiration (expiration, respiration, spirit) from Arabic zafeer, zafrat 'expiration, breath' in which /z & f/ turned into /s & p/ respectively. Intestine from Arabic miSraan 'intestine'; /m & r/ became /n/ while /S/ split into /s & t/. Iris 'messenger of God in Greek' from Arabic rasool 'messenger' via lexical shift and /l & r/-merger. Jaw (jaw-jaw) from Arabic fakk 'jaw' via reversal and turning /k & f/ into /j & w/, shadq, shudooq (pl.) 'jaw' where /sh, d, & q/ merged into /j/, or 2anak 'jaw' via /2 & k/-merger into /j/ and /n/-loss (cf. ja3ja3 'talk out loud' via /3/-loss; jumjuma(t) 'cranium' via lexical shift, syllable merger and turning /m/ into /w/; ju'ju' 'bird's breast' and ja'aaji' 'visible bones when too thin' via syllable loss and lexical shift). Kidney from Arabic kilia(t), kalaawi (pl.) 'kidney' via reordering and turning /l & t/ into /d & n/ respectively. Knee from Arabic rukba(t), rukab (pl.) 'knee' via reordering and merging /r & b/ into /n/. Lap from Arabic 'urbia(t), 'urab (pl.) 'thigh base' via /r/mutation into /l/, /'/-loss, and lexical shift, wabila(t) 'thigh head' via reversal and /w & l/-merger into /l/, or rabla(t) 'inner thigh flesh; thick meat' via /r & l/-merger into /l/. Larynx (laryngeal) from Arabic 2unjura(t), 2anaajir (pl.) 'larynx' via reordering, turning /2 & j/ into /k & s/, and /l/split from /r/. Lash (eyelashes) from Arabic rimsh '(eye) lash' in which /r & m/ merged into /l/ (cf. whiplash from Arabic jald 'whiplash' via reversal and turning /j/ into /sh/). Leg from Arabic rijl 'leg, foot' where /r & l/ merged and /j/ changed to /g/ or kiraa3 'leg' via reversal, merging /k & 3/ into /g/, and turning /r/ into /l/. Lid (eyelid) from Arabic Dhil 'shadow, shield' via reversal and turning /Dh/ into /d/. Lingua (lingual, linguist, linguistics, langue, language; tongue) from Arabic lisaan 'tongue' via reordering and changing /s/ to /g/ (see tongue below). Lip from Arabic balam 'lip swell; shut up' via lexical shift, reordering, and /m & b/ merger or subala(t) 'part of lip, moustache' via reversal and /s & l/-merger (cf. lub (lubaab) 'heart, inner' via lexical shift; lab(l)ab 'top breast; of animals, to lick and fondle baby with lips; to be kind and gentle' via lexical shift; labba(t), labab 'neck-slaughter area, necklace area' via lexical shift; liblib or bilbil 'talker, big mouth' via lexical shift). Liver 'seat of love and passion' from Arabic roo2 'soul, spirit' in which /2/ changed to /v/ and /l/-split from /r/ or lubb 'inner; heart' where /b/ became /v/ and /r/ was inserted). Lobe from Arabic waabil 'knee joint bone' via lexical shift and /l & w/-merger. Loin (sirloin, tenderloin) (Latin lumbus 'animal body side for food') from Arabic la2m 'meat' via /2/-loss and turning /m/ into /n/ or mail 'side' via reversal and turning /m/ into /n/.

8|P a ge

International Journal of Current Applied Linguistics and English Literature- Vol.1, Issue, 2, pp. 3, 14, 2013

Lumbar (lumbo) (via Latin lumbus 'animal body side for food' from Arabic la2m 'meat' via /2/-loss, turning /m/ into /n/, and /b/-insertion. Lung 'little, not heavy in Old English' from Arabic qaleel 'small' via reversal and turning /q & l/ into /g & n/ or mi3laaq, 3allaq (v) 'lungs, suspension, hang' via reordering, merging /3 & q/ into /g/, and changing /m/ to /n/) (cf. 3unuq 'neck, connection' via lexical shift, /3/-loss, and /l/-split from /n/). Male (masculine) via French masle and Latin masculus 'male, adult' from Arabic zalama(t), zulm (pl.) 'man, male' via reordering and /z/-split into /s & k/, which turned into zero later. Mammal 'with teats' from Arabic maama 'mother' via lexical shift. Man (human, humanity; woman) from Arabic nama, 'anaam (pl.) 'child, humans, men' via reversal and turning /'/ into /h/ in human or from 'insaan 'human' where /'/ became /h/ while /s & n/ merged into /m/ (cf. German Mensch from Arabic 'insaan 'human' via reordering and turning /n & s/ into /m & sh/; animal in Jassem (2012d, g)). Manu (manual) from Arabic anamil 'fingers' via reversal and /l/-merger into /n/. Marrow from Arabic mukhkh 'marrow' where /kh/ split into /r & w/ (cf. 2amar 'red' via lexical shift and /2/-loss). Maw 'stomach in Old English, German Majen' from Arabic ma3ee 'intestine' via lexical shift and /3/-change to /w/. Meat from Arabic damm 'blood' via lexical shift, reversal, and turning /d/ into /t/ or Ta3aam 'food' via lexical shift, reversal, and /3/-loss. Menopause from a combination of Arabic damm 'blood' via reversal and turning /d/ into /n/ and 2abs 'pause' via /2/loss or merger into /s/. Mind (mental) (Old English gemynd 'memory, thought, intention'; Latin mens 'thought') from Arabic dhihn 'mind' via reordering, turning /dh & h/ into /d & g ()/, and /m/split from /n/. Molar from Arabic 3umoor 'inter-teeth flesh' via /3/-loss, /l/-insertion, and lexical shift. Mouth from Arabic fam 'mouth' (tim, thum, uthum in Syrian Arabic (Jassem 1993, 1994a-b) via reversal and turning /f/ into /th/. Mucus (mucous) from Arabic mukhaaT 'mucus''; /kh & T/ passed into /k & s/. Muscle (mouse) 'little mouse' from a combination of Arabic sha2m 'fat' via reversal, lexical shift, and merging /sh & 2/ into /s/ and qal(eel) 'little' where /q/ became /k/. Nail from Arabic anmala(t) 'nail under-part' via lexical shift and /n & m/-merger or na3l, ni3aal (pl.) 'shoe, underfoot' via lexical shift and /3/-loss. Navel (French ombril, nombril; German Nabel) from Arabic 2abl 'cable' or 2aaliban 'naval veins' via lexical shift, reordering and turning /2 & b/ into /v & n/ each, ma'na(t), mu'oon (pl.) 'navel' via reordering and turning /m & t/ into /v & l/, mathaana(t) 'bladder' via lexical shift and turning /m, th, & n/ into /n, v, & l/, or thunna(t) 'navel and groin area' through reordering and changing /th & t/ into /v & l/.

Neck from Arabic 3unuq 'neck' through /3/-deletion and /q/-mutation into /k/ (cf. knock from naqaq, naqnaq 'knock'). Nerve (nervous, neuron, neurology) from Arabic 3aran '(cooked) meat' via reversal, turning /3/ into /v/, and lexical shift or na3ra(t) 'nasal soft bone' via lexical shift, reordering, and changing /3/ to /v/ (cf. vein below). Nipple from Arabic nibaal 'arrow' or laban 'milk' via reversal and lexical shift. Nose (nasal) from Arabic anf 'nose' in which /f/ changed to /s/ or khashm 'nose' via reversal, turning /m/ into /n/ and /kh & sh/-merger into /s/ (cf. nostril below). Nostril from Arabic nukhra(t), minkhar 'nose head or hole' via reordering and turning /kh/ into /s/. Ocular (oculist) (Latin oculus 'eye') from Arabic 3ain, 3uyoon, a3yun (pl.) 'eye'; /3 & n/ turned into /k & l/ each. Omen (ominous) from Arabic yameen 'right (hand)' via lexical shift and turning /y/ into /o/ (cf. ominous from Arabic man2oos 'ominous' via /2/-loss; arm above). Opaque (opacity) from Arabic ghabaasha(t) 'opacity' via reversal and /gh & sh/-merger into /k/. Ophthalmic (ophthalmology) 'eye in Latin and Greek' from Arabic baSar, ibSaar 'sight'; /b, S, & r/ turned into /f, th, & l/ in that order besides /m/-insertion. Optic (optics) 'sight and light (science)' (Latin opticus and Greek optimos) from Arabic baSar, baSeera(t) 'sight' where /S & r/ turned into /k & t/ or merged into /k/ or baSS(at) 'look, sight' in which /S/ became /t/ (cf. shabah, shubhat 'sight, likeness' via reordering and /sh & h/-merger into /k/). Oral (Latin os (genitive oris) 'mouth, opening, face, entrance') from Arabic fooh 'mouth, opening' via reversal and /f & h/-merger into /s/. Organ (organization) (Latin organum, Greek organon 'tool, musical instrument, organ of body/sense') from Arabic 3irq 'vein, off-shoot' via reordering and turning /q & 3/ into /g & n/. Orifice (Latin orificium 'opening') from Arabic furja(t) 'opening' via reordering and turning /j/ into /s/ or thaghr 'opening, mouth' via reordering and turning /th & gh/ into /f & s/. Osteopath (Greek osteon 'bone' and pathos 'suffering, disease, feeling') from Arabic 3aDhm 'bone' where /3, Dh, & m/ turned into /s, t, & n ()/ and ba's, bu's 'disease, suffering' via /'/-loss and turning /s/ into /th/. Ova (oval, ovulation) from Arabic baiDa(t) 'egg, ovum' in which /b & D/ merged into /v/ (cf. ovation from Arabic 2aia, ta2iat 'greet' where /2/ became /v/ (Jassem 2012b, 2013c). Palate (palatal) from Arabic balaaT 'flat stone, tile' via lexical shift and the change of /T/ to /t/ or Tabla(t) 'drum' via reordering. Palm from Arabic baahim, ibhaam 'thumb' via lexical shift, /h/-loss, and /l/-insertion. Pelvis from Arabic Sulb 'backbone' via lexical shift, reversal and splitting /b/ into /v & b/ or wabila(t) 'thigh head' via lexical shift, reordering, and turning /w & t/ into /v & s/. Penis 'tail in Latin' from Arabic dhanab 'tail' via reversal and changing /dh/ to /s/ (cf. zabr 'penis' via reordering and turning /z & r/ into /s & n/).

9|P a ge

International Journal of Current Applied Linguistics and English Literature- Vol.1, Issue, 2, pp. 3, 14, 2013

Person (personality) from Arabic bashar 'person' via reordering, turning /sh/ into /s/, and /n/-insertion (cf. parson from Arabic basheer 'bringer of good news' or Saboor 'persevering' via reordering, turning /sh & S/ into /s/, and /n/-insertion). Phallus (phallic) from Arabic faishala(t) 'penis tip' via reordering and turning /sh/ into /k (s)/ or silf 'penis skin' via reversal, turning /s/ into /k/, and lexical shift (cf. Phyllis (philo-) 'loving girl in Greek' from Arabic laabbat 'loving woman', labab, lablab 'of animals, to love and lick their babies; to be kind and gentle' via reversal and turning /b & t/ into /f & s/). Pharynx via Greek pharanx 'windpipe, cleft, chasm' from Arabic fa(l/r)aq, faraj, falakh 'division, cut'; /q/ split into /ks/ while /l/ into /r & n/. Phlegm from Arabic balgham 'phlegm'; /gh/ became /g/. Piss from Arabic bazz 'of liquids, to come out from within' where /z/ became /s/ or basbas 'flow, pass' via syllable loss. Pit (armpit) from Arabic ibT 'arm pit'. Pneumatic (pneumonia) from Arabic nasma(t) 'wind' where /s/ merged into /n/ besides /p/-insertion. Pneumonia (pneumatic) from Arabic maree' 'windpipe' via lexical shift, reordering, /r/-split into /n & n/, and /p/insertion. Pore (porous) from Arabic bu'ra(t) 'hole, pore'. Psyche (Greek psykhe 'soul, mind, spirit, breath, life' from Arabic nafkh(at) 'blow, breath' via reordering and turning /f & n/ into /p & s/. Pubic (puberty 'becoming adult') from Arabic isb, asaab/usoob (pl.) 'pubic' via reversal, /b/-duplication, and turning /s/ into /k/ (cf. shab(aab) 'young adult' via reversal and turning /sh/ into /k/; zubb, zibaab (pl.) 'penis' via reversal, /b/-duplication, and turning /z/ into /k/). Pulmonary from Arabic bal3oom 'windpipe' via lexical shift, /3/-loss, and /n/-split from /m/ (cf. Old Church Slavonic plusta, Lithuania plauciai 'lung' from Arabic fashsha(t) 'lung'; /f & sh/ became /p & s/ besides /l/insertion). Pupil from Arabic bu'bu' '(eye) pupil' via /l/-insertion and /'/-loss. Retina from Arabic naseej 'knit' via reversal, lexical shift, and turning /s & j/ into /r & t/ or naDhar 'sight' via reversal and turning /Dh/ into /t/. Rib from Arabic taraa'ib 'rib bones' via /t & r/-merger (cf. irb 'piece, part'; urbia(t) 'thigh base' via lexical shift). Saliva from Arabic tufaal 'saliva' via reordering and turning /t/ into /s/ or lu3aab 'saliva' via reordering and changing /3/ to /s/. Scalp from Arabic Sal3ooba(t) 'scalp, skull skin' via reordering and changing /3/ to /k/. Scrotum from Arabic Surrat 'bag' or surrat 'navel' via lexical shift and /S (s)/-split into /s & k/ (cf. khaaSirat 'waist' via lexical shift and turning /kh & S/ into /k & s/). Self from Arabic nafs 'self' via reordering and turning /n/ into /l/. Semen (insemination) from Arabic meni 'semen' where /s/ split from /n/ or madhee 'pre-semen' via reordering, turning /dh/ into /s/, and /n/-split from /m/ (cf. samn 'fat, butter' via lexical shift).

Sex 'person and sex in Greek' from Arabic shakhS 'person' where /sh, kh, & S/ became /s, k, & s/ in that order or kuss 'vagina' via reversal and lexical shift. Shit from Arabic shaT, zaT 'shit'; /z & T/ turned into /sh & t/. Shield from Arabic jild 'skin' in which /j/ turned into /sh/. Shoulder from Arabic Sadr, Sudoor (pl.) 'breast' via lexical shift, turning /S/ into /sh/, and /l/-insertion; asdaraan 'shoulders; neck veins; area between shoulder and neck' via reordering and changing /s & n/ to /sh & l/; saa3id 'forearm' where /s & 3/ merged into /sh/ besides /l & r/-insertion; or dhiraa3 'arm' via reordering and turning /dh & 3/ into /d & sh/ (cf. kardoos 'hand' via reordering and merging /k & s/ into /sh/; qurdooda(t) 'top back' via lexical shift and turning /q & r/ into /sh & l/; kanad 'shoulder area' where /k/ became /sh/). Shrimp from Arabic sha(waa)rib 'moustaches' via /m/insertion or shanab 'moustache' in which /n/ split into /r & m/. Sinusitis (nose, nostril) from Arabic khashm 'nose' via reordering, merging /kh & sh/ into /s/, and turning /m/ into /n/ or anf 'nose' via reversal and /f/-change to /s/. Sinew from Arabic naseej 'knitting' via reordering and merging /s & j/. Sirloin (loin) (French 'upper loin') from Arabic Dhahr 'upper, back' via /Dh & h/-merger into /s/; for loin, see above. Skeleton (skeletal) 'bones in Latin; dried-up body in Greek' from Arabic saaq, seeqaan (pl.) 'leg' via lexical shift and turning /q/ into /k/ and /l & t/-insertion, kalkal 'breast area' via lexical shift and turning /k/ into /s/, kaahil 'top back and neck' via reordering and turning /h/ into /s/, 3aSqool 'thin leg' via lexical shift and /3 & S/-merger into /s/, haikal(at) 'skeleton' where /h/ became /s/ and /n/ was inserted, or qaSalat 'dried-up long grass or stick' via reordering and lexical shift (cf. Greek sclero 'hard' from Arabic Sakhr 'rock, hard' (Jassem 2013f)). Skin from Arabic salkh 'skin' via reordering and turning /kh & l/ into /k & n/ (cf. su2nat 'skin colour' where /2/ became /k/ besides lexical shift). Skull from Arabic 3aql 'brain, mind' via lexical shift and turning /3 & q/ into /s & k/ respectively (cf. skill from Arabic 2eel(at) 'skill, deception, ability' where /2/ split into /s & k/). Sole from Arabic saafil 'low' via /s & f/-merger into /s/. Soul from Arabic roo2 'soul, spirit' via reversal and changing /r & 2/ into /l & s/ or zawaal (zol in Sudanese Arabic) 'soul, person, shadow' where /z/ became /s/. Spit (spat) from Arabic ba(S/z)aq 'spit' via reordering and turning /q/ into /s/. Spine (spinal) from Arabic Sulb 'spine' via reordering and turning /S & l/ into /s & n/ each or 3aSab 'nerve' via lexical shift, reordering, and turning /3 & S/ into /n & s/. Spleen 'seat of morose feelings' from Arabic Saaboon 'soap' via lexical shift and /l/-insertion or baSal 'onion; onion-shaped' via lexical shift, reordering, and /n/insertion. Stomach (Greek stoma 'mouth') from Arabic fam (tim, thum, uthum in Syrian Arabic (Jassem 1993, 1994a-b) 'mouth' where /f/ split into /s & t/ (cf. ma3id(at) 'stomach' via reordering and turning /3, d, & t/ into /k, t, & s/;

10 | P a g e

International Journal of Current Applied Linguistics and English Literature- Vol.1, Issue, 2, pp. 3, 14, 2013

Simaakh 'ear canal' via lexical shift, changing /S & kh/ to /s & ch/, and /t/-insertion). Stool from Arabic kalta(t) 'stool' via reordering and turning /k/ into /s/, sal2(at) 'animal loose foul' via /2/-loss or shall, shilaal 'baby's diarrhea' where /sh/ split into /s & t/. Sweat from Arabic Sahak 'sweat smell' where /S, h, & k/ became /s, w, & t/ in that order. Tear (eye tear) from Arabic qaTr(at) or dharaf 'drop, tear'; /q & T/ and/or /dh & f/ merged into /t/. Teats from Arabic thadi 'teats'; /th & d/ merged into /t/. Temple from Arabic Tabla(t) '(ear) drum' via /m/-split from /b/ or qibla(t) 'chapel, direction' in which /q/ turned into /t/. Testis (testicle) from Arabic khiSia(t) 'testes' where /kh/ became /t/ and qal(eel) 'small' where /q/ became /k/ (cf. Teez 'bottom, vagina' via lexical shift and /z/-split into /s & t/). Thigh from Arabic fakhdh 'thigh'; /f & dh/ merged into /th/ while /kh/ changed to /gh/. Thorax (thoracic) from Arabic zawr 'top-to-mid breast' where /z/ split into /th & k(s)/ or Sadr 'breast' via reordering and turning /S & d/ into /ks & th/ each. Throat from Arabic zawr 'throat' via reordering and /z/split into /th & t/ or turquat 'windpipe' where /t & q/ became /th & t/ each (cf. zaraT 'to swallow' where /z/ became /th/). Thumb from Arabic iSba3 'finger' where /S & 3/ changed to /th & m/ or baahim 'thumb' via reordering and turning /h/ into /th/. Tip (tongue tip) from Arabic dhab (or dhubaab) 'tip' where /dh/ changed to /t/. Toe from Arabic Difda3 'a bone in horse feet' where /D, f, & d/ merged into /t/ and /3/ was lost (cf. Dil3 'rib' via lexical shift, /l/-merger into /w/, and /3/-loss). Tongue (German Zunge, Latin lingua, French langue) from Arabic lisaan 'tongue' via reordering and turning /l & s/ into /t & g/ respectively. Tooth (dental, dentist) from Arabic thania(t) 'tooth' where /n/ merged into /t/ or Dirs 'tooth, molar' in which /D & s/ turned into /t & th/ besides /r/-loss. Trachea from Arabic loan taraaq 'windpipe'; /q/ became /k/. Trunk from Arabic kharToom 'trunk' via reordering and turning /kh, T, & m/ into /k, t, & n/ or Tarqa(t), miTraq 'straight, solid rod' where /q/ became /k/ and /n/ was inserted. Tube from Arabic qaSab 'reed' where /q & S/ merged into /t/ (cf. qaDeeb 'stick' where /q & D/ merged into /t/; tub from Arabic jaabia(t) 'trough' where /j/ became /t/ (Jassem 2013e). Tummy from Arabic baTn(i) 'belly'; /b & n/ merged into /m/. Urine (urology) from Arabic yaroon 'horse semen' via lexical shift, mar(mar) 'rain' via lexical shift, reversal, and turning /m/ into /n/, or baul 'urine' via reversal and turning /b & l/ into /n & r/ respectively. Uterus 'belly, womb' from Arabic baTn, buToon (pl.) 'belly' where /b & n/ turned into /v (u) & r/ (cf. Greek hystera 'womb' from Arabic khaaSirat 'waist' via lexical shift, reordering, and turning /kh/ into /h/; Latin vederas 'stomach' and Old Church Slavonic vedro 'bucket, barrel'

from Arabic baTn 'belly' where /b, T, & n/ became /v, d, & r/). Uvula from Arabic laha(t) 'uvula' via reordering and /h/mutation into /v/. Vagina from 3ijaan 'vagina' where /3/ became /v/ or farj 'vagina' via reordering and turning /r/ into /n/. Vein from Arabic na3ar, naa3ir 'bleeding vein' via reordering, /n & r/-merger, and turning /3/ into /v/ (cf. 'inaa', awani (pl.) 'container' where /' (w)/ became /v/ and 3ain 'eye' via lexical shift and changing /3/ into /v/; see nerve above). Velum (velar; veil; reveal, revelation) 'a sail, awning, curtain, covering in Latin' from Arabic li2aaf 'covering, quilt' or lifaa3 'veil, mantle' via reversal and merging /2 (3) & f/ into /v/. Ventricle (Latin venter 'abdomen' and French cle 'small') from a combination of Arabic baTn 'belly' via reordering and the change of /b & T/ to /v & t/ and qall, qaleel 'little, small' where /q/ became /k/ (Jassem 2013a). Vertebra (vertebrate) from Arabic furDat 'piece (of meat)' where /D/ became /t/ and /b/ split from /f/ besides /r/insertion or faqarat 'vertebra' via reordering and changing /q/ to /t/ besides /b/-split from /f/. Vessel from Arabic Saafen 'blood vessel' via reordering and turning /n/ into /l/ (cf. sufun 'ship' via reordering and turning /n/ into /l/; 2a(w)asel 'vessel, container, bird's stomach' where /2 & S/ became /v & s/). Visa-vis from Arabic wajh 'face' where /w/ became /v/ while /j & h/ merged into /s/. Voice (vocal) from Arabic 2iss 'voice, feeling'; /2/ became /v/. Vulva (Latin volva 'wrapper' and volvere 'turn, revolve') from Arabic laffa 'turn, wrap' via reordering or mahbal 'vulva' via reordering and turning or merging /m, h, & b/ into /v/ (cf. qubul 'vagina' where /q & b/ became /v/; 2ir2 'vagina' where /2 & r/ became /v & l/ each; fawha(t) 'opening' via /h/-mutation into /v/ and /l/-insertion). Waist from Arabic wasaT 'waist, middle' (cf. khaSir(at) 'waist' in which /kh/ changed to /w/ and /r/ merged into /s/). Windpipe from Arabic nada 'dew, wet wind' via reversal and beeb 'pipe' (see Jassem 2012d). Womb from Arabic umm 'mother' via /b/-insertion and lexical shift or ra2im 'womb' in which /2/ turned into /w/ while /r/ merged into /m/ besides /b/-insertion. Wrist from Arabic rusgh 'wrist'; /gh/ became /w/ while /t/ split from /s/. Yard from Arabic yad 'hand' via /r/-insertion or dhiraa3 'shoulder, arm' via reversal and turning /3/ into /y/. In summary, the above body part terms amount to a little over 200, all of which have Arabic cognates. That is, the percentage is 100%.

DISCUSSION

The results above show that body part terms in Arabic, English, German, French, Latin, and Greek are true cognates, whose differences are due to natural and plausible causes of phonetic, morphological and semantic change. Therefore, they support all former such studies: namely, the investigation of numeral words (Jassem 2012a), common religious terms (Jassem 2012b), pronouns (Jassem 2012c), determiners (Jassem 2012d), verb to be

11 | P a g e

International Journal of Current Applied Linguistics and English Literature- Vol.1, Issue, 2, pp. 3, 14, 2013

forms (Jassem 2012e), inflectional 'gender and plurality' markers (2012f), derivational morphemes (2013a), negative particles (2013b), back consonants (2013c), water and sea words (2013d), air and fire terms (Jassem 2012e), celestial and terrestrial terms (Jassem 2013f), and animal terms (Jassem 2013g) in English, German, French, Latin, Greek, and Arabic which were all found to be not only genetically related but also rather dialects of the same language. The percentage of shared vocabulary between Arabic and English, for instance, was 100% in all studies. According to Cowley's (1997: 172-173) classification, such ratio indicates that they belong to the same language (i.e., dialects). In light of such results, the lexical root theory has been found as adequate for the present analysis. The main principle which states that Arabic, English, and so on are not only genetically related but also are dialects of the same language is once again verifiably sound and empirically true, therefore. Relating English body part terms to true Arabic cognates proves that very clearly. The applied procedures of the lexical root theory operated neatly and smoothly. Lexicologically, the lexical root proved to be an adequate, analytic tool for relating body part words in Arabic and English to each other by focusing on root consonants and overlooking vowels as the former carry word meaning while the latter convey phonetic and morphological information as described in section (1.) above (Jassem 2012a-f, 2013a-g). For example, auricle and nasality are stripped down to their 'underlined' roots first. Etymology or the historical origin and meaning of lexical items plays a paramount importance. In fact, tracing the Latin, Greek, French, and German roots of English words facilitates locating their Arabic origins a lot. For example, English ear (auricle) and hear, German Ohr and hren, and Latin aura/auris all come from Arabic 3air 'ear' via different sound changes: (a) reordering, (b) turning /3/ into /h/ in German and /s/ in Latin, and (c) its deletion in English and Latin; in all, /3/ evolved into /h, s, or /; English and French audition/audio, Latin auditio/audire derive from Arabic udhun 'ear' by turning /dh/ into /d/ into which /n/ merged (see 3. above). The linguistic analysis showed how words can be genetically related to and derived from each other phonetically, morphologically, grammatically and semantically. The phonetic analysis was pivotal in this regard in view of the enormous changes which affected Arabic consonants especially in English and other European languages as well as mainstream Arabic varieties themselves (e.g., Jassem 1993, 1994a, 1994b). These changes included deletion, reversal, reordering, merger, split, insertion, mutation, shift, assimilation, dissimilation, palatalization, spirantization (velar softening), duplication, syllable loss, resyllabification, consonant cluster reduction or creation and so on. The commonest such changes were reversal, reordering, split, and merger, some of which may be the result of changing the direction of Arabic script from right to left at the hands of the Greeks, its first borrowers (Jassem 2013h). The above results are rife with examples, a brief outline of which can be found in Jassem (2013c), tackling the major

sound changes affecting back consonants: i.e., velars, uvulars, pharyngeals, and glottals. Besides, the results clearly demonstrate that sound change proceeds in three different paths (Jassem 2012a-f, 2013ag). First, it may be multi-directional where a particular sound may change in different directions in different languages at the same time. For example, Arabic 3air 'ear' led to ear and hear in English, auris (auriculis) in Latin, and auricle in French via different sound changes as has just been mentioned above. Audience, audio in English, Latin auditio (audire 'to hear'), and French audio are another example, which all come from Arabic udhun 'ear' through the merger of /dh & n/ into /d/. Secondly, it may be cyclic where more than one process may be involved in any given case. The changes from Arabic karsh(at) 'stomach' to English gastro, gastric, for example, included (i) reordering, (ii) turning /k & sh/ into /g & s/, and (iii) vowel shift. Finally, it may be lexical where words may be affected by the change in different ways- i.e., lexical diffusion (see Phillips 2012: 1546-1557; Jassem 1993, 1994a, 1994b for a survey). That is, a particular sound change may operate in some words, may vary in others, and may not operate at all in some others. The data is full of examples like the different forms of English ear, hear, auricle, German Ohr, hren 'hear', and Latin and French auricle, auris, which descend from Arabic 3air 'ear' (3. above). All such factors make Arabic, English, German, and French mutually unintelligible despite the use of the same word roots (Jassem 2012a-b). It is worth noting that all the sound changes above are natural and plausible; for example, the change of /dh/, a voiced interdental fricative, in Arabic udhun 'ear' to /d/, a voiced alveolar stop in audio, is natural as both have the same place and voice (cf. Jassem 2012b). Likewise, the change of /k/ in karshat 'stomach' to /g & s/ in gastric is natural. (For further detail, see Jassem (2012a-f, 2013a-b).) Regarding the morphological and grammatical aspects (inflectional and derivational affixes), all relate to number, gender, and verb- or adjective-making ones. Jassem (2012f, 2013a) has already described them in detail, to which the curious reader may be referred. In fact, since all such differences do not alter the meaning of the root itself, they can be ignored right away. Finally, semantically, all types of lexical relationships occurred as reported in Jassem (2012a-f, 2013a-g). Lexical stability was obvious in a great many words such as eye, nose, head, back, dorsal, canine, dental, gingival, gynecology, gastro/gastric, leg, arm, heart, cardiac, cranium, ass, arse, vagina, penis, dick, etc., whose cognates still retain the same or similar forms and meanings in Arabic, English, French, and so on. Lexical shift was very common where meanings shifted within the same broader category such as Arabic sinn 'tooth' and canine 'dog, tooth', its current meaning in English; shoulder might have come from Arabic Sadr, Sudoor (pl.) 'breast' or saa3id 'forearm'; arm (arms, army) derives from Arabic yameen 'right (hand)' where /n/ became /r/. Lexical change is often linked to lexical shift such as omen which comes from Arabic yameen 'right (hand)' and which indicates the good and positive in the future. Lexical split

12 | P a g e

International Journal of Current Applied Linguistics and English Literature- Vol.1, Issue, 2, pp. 3, 14, 2013

took place in words like yameen 'right (hand)' which yielded arm and omen through different phonetic processes: in one reordering and turning /n/ into /r/ happened while /y/ became /o/ in the other; Sadr 'breast' split into heart where /S & d/ became /h & t/ and shoulder where /S/ became /sh/ besides /r/-insertion; Arabic 3air 'ear' gave ear and hear; Arabic damm 'blood' produced blood, hemo, anemia, and meno- (3. above). The abundance of several formally and semantically similar words in Arabic led to lexical convergence. For example, tooth might derive from Arabic thaniat 'tooth' or Dirs 'molar' through turning /th & D/ into /t/ and /r & n/loss; jaw, lap are other examples. It also led to lexical multiplicity in words like dent 'tooth; damage; bend' which derive from Arabic thaniat 'tooth' and thana, thaniat 'bend' where /th/ became /d/; the data is full of examples like ass (see 3. above). Finally, lexical variability is manifested in the presence of alternative words for the same object or concept such as eye and ear in both Arabic and English, which are utilized in different ways. For example, English eye, ocular; ear, auricle, hear; cardiac, heart are a few such examples (see 3. above). All Arabic words have several variants (e.g., Ibn Seedah 1996), many of which underwent lexical or semantic shift in English within the same broader category, of course, as shown above. As to the relational procedure, many of the above lexical cognates are both formally and semantically similar as in ear, auri- and Arabic 3air 'ear' via /3/-loss; gastric and Arabic karsha(t) 'stomach' where /k & sh/ became /g & s/. Some, however, are formally different but semantically similar such as canine 'tooth; dog-related', which derive from Arabic sin 'tooth'. Others still are formally similar but semantically different such as ear and eros/erotic in English, which come from similar Arabic cognates: i.e., 3air 'ear' and 3aroos 'bride' or air 'penis' via different sound changes such as /3/-loss (see 3. above). Thus Arabic cognates can be clearly seen to account for the formal similarities and/or differences between English words themselves. In summary, the foregoing body part words in Arabic, English, German, French, Latin, and Greek are true cognates with similar forms and meanings. Arabic can be safely said to be their origin all for which Jassem (2012a-f, 2013a-g) gave some equally valid reasons such as phonetic complexity, lexical multiplicity and variety. Of course, English, German, French, and Latin do have lexical variety and multiplicity but not to the same extent as Arabic does. One can compare for himself the number of terms for eye, ear, stomach, nerve, bone, finger, hand in English dictionaries and thesauri and Arabic ones like Ibn Seedah (1996).

ii.

iii.

iv.

v.

across those languages are due to natural and plausible phonological, morphological and/or lexical factors (cf. Jassem 2012a-f, 2013a-g). The main phonetic changes included reversal, reordering, split, and merger whereas the recurrent lexical patterns were stability, convergence, multiplicity, shift, and variability; the abundance of convergence and multiplicity stem from the formal and semantic similarities between Arabic words from which English words emanated. The huge lexical variety and multiplicity of Arabic body part terms as well as their phonetic complexity compared to those in English and European tongues point to their Arabic origin in essence. The lexical root theory has been as adequate for the analysis of the close genetic relationships between Arabic, English, German, French, Latin, and Greek body part terms. Finally, the current work agrees with Jassem's (2012a-f, 2013a-g) calls for further research into all language levels, especially vocabulary. Furthermore, the application of such findings to language teaching, lexicology and lexicography, translation, cultural (including anthropological and historical) awareness, understanding, and heritage is urgently needed for promoting and disseminating linguistic and cultural understanding, enrichment, acculturation, equality, tolerance, and coexistence..

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank everyone who contributed to this research in any way worldwide. For my supportive and inspiring wife, Amandy M. Ibrahim, I remain indebted as ever.

References

1. Algeo, J. (2010). The origins and development of the English language. (6th edn.). Wadsworth Cengage Learning. Altha3aalibi, Abu ManSoor. (2011). Fiqhu allughat wa asraar al3arabiyyat. Ed. by Alayoobi, Dr. Yaseen. Beirut and Saida: AlMaktabat Al-3aSriyyat. Bergs, Alexander and Brinton, Laurel (eds). (2012). Handbook of English historical linguistics. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Campbell, L. (2006). Historical linguistics: An introduction. (2nd edn). Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press. Celce-Murcia, M., Brinton, D.M., Goodwin, J.M., & Griner, B. (2010). Teaching pronunciation: A course book and reference guide. (2nd edn). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Crowley, T. (1997). An Introduction to historical linguistics. (3rd edn). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Crystal, D. (2010). The Cambridge encyclopedia of language. (3rd ed). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

2.

3.

4. 5.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

To sum up, the main results of this paper are as follows: i. The 200 body part terms or so in English, German, French, Latin, Greek, and Arabic are true cognates with similar forms and meanings. However, the different forms amongst such words 6.

7.

13 | P a g e

International Journal of Current Applied Linguistics and English Literature- Vol.1, Issue, 2, pp. 3, 14, 2013

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

Harper, Douglas. (2012). Online etymology dictionary. Retrieved http://www.etymonline.com (January 10, 2013). Ibn Khalawaih, Ahmad. (2013). Kitaabu alibli. Retrieved http://www.fustat.com/adab/asmaalasad.pdf (March 4, 2013). Ibn Manzoor, Abi Alfadl Almisri. (2013). Lisan al3arab. Beirut: Dar Sadir. Retrieved http://www.lisan.com (January 10, 2013). Ibn Seedah, Ali bin Ismail. (1996). AlmukhaSSaS. Beirut: Daar I2ya Alturath Al3arabi and Muassasat Altareekh al3arabi. Jassem, Zaidan Ali. (1993). Dirasa fi 3ilmi allugha al-ijtima3i: Bahth lughawi Sauti ijtima3i fi allahajat al3arabia alshamia muqaranatan ma3a alingleeziyya wa ghairiha. Kuala Lumpur: Pustaka Antara. _______. (1994a). Impact of the Arab-Israeli wars on language and social change in the Arab world: The case of Syrian Arabic. Kuala Lumpur: Pustaka Antara. ________. (1994b). Lectures in English and Arabic sociolinguistics, 2 Vols. Kuala Lumpur: Pustaka Antara. ________. (2012a). The Arabic origins of numeral words in English and European languages. International Journal of Linguistics 4 (3), 225-41. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5296/ijl.v4i3.1276 ________. (2012b). The Arabic origins of common religious terms in English: A lexical root theory approach. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature 1 (6), 59-71. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/ijalel.v.1n.6p.59 ________. (2012c). The Arabic origins of English pronouns: A lexical root theory approach. International Journal of Linguistics 4 (4), 83-103. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5296/ijl.v4i4.227. ________. (2012d). The Arabic origins of determiners in English and European languages: A lexical root theory approach. Language in India 12 (11), 323-359. URL: http://www.languageinindia.com. ________. (2012e). The Arabic Origins of Verb ''To Be'' in English, German, and French: A Lexical Root Theory Approach. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature 1 (7), 185-196. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/ijalel.v.1n.7p.185.

20. ________. (2012f). The Arabic origins of number and gender markers in English, German, French, and Latin: a lexical root theory approach. Language in India 12 (12), 89-119. URL: http://www.languageinindia.com. 21. ________. (2013a). The Arabic origins of derivational morphemes in English, German, and French: A lexical root theory approach. Language in India 13 (1), 48-72. URL: http://www.languageinindia.com. 22. ________. (2013b). The Arabic origins of negative particles in English, German, and French: A lexical root theory approach. Language in India 13 (1), 234-48. URL: http://www.languageinindia.com. 23. ________. (2013c). The English, German, and French cognates of Arabic back consonants: A lexical root theory approach. International Journal of English and Education 2 (2): 108-128. URL: http://www.ijee.org. 24. ________. (2013d). The Arabic origins of "water and sea" terms in English, German, and French: A lexical root theory approach. Language in India 13 (2): 126-151. URL: http://www.languageinindia.com. 25. ________. (2013e). The Arabic origins of "air and fire" terms in English, German, and French: A lexical root theory approach. Language in India 13 (3): 631-651. URL: http://www.languageinindia.com. 26. ________. (2013f). The Arabic origins of "celestial and terrestrial" terms in English, German, and French: A lexical root theory approach. International Journal of English and Education 2 (2): 323-345. URL: http://www.ijee.org. 27. ________. (2013g). The Arabic origins of "animal" terms in English and European languages: A lexical root theory approach. Language in India 13 (4). URL: http://www.languageinindia.com. 28. ________. (2013h). Good English pronunciation. URL: http:// www.iktab.com (March 1, 2013). 29. Phillips, Betty S. (2012). Lexical diffusion. In Bergs, Alexander and Brinton, Laurel (eds), 1546-1557. 30. Pyles, T. and J. Algeo. (1993). The origins and development of the English language. (4th edn). San Diego: HBJ.

How to cite this article: Zaidan Ali Jassem: The arabic origins of body part terms" in english and european languages: a lexical root theory approach. International Journal of Current Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 2013; 1(1); 3-14.

14 | P a g e

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Beehive 3 Students Book (British)Document138 pagesBeehive 3 Students Book (British)Квіталіна Сергієнко100% (2)

- English Syllabus - Class 7 - Stage 8 - Cambridge Checkpoint 2019-2020Document9 pagesEnglish Syllabus - Class 7 - Stage 8 - Cambridge Checkpoint 2019-2020Pooja BhasinNo ratings yet

- Linguistic ImperialismDocument3 pagesLinguistic Imperialismapi-210339872100% (2)

- Ethiopic An African Writing System PDFDocument2 pagesEthiopic An African Writing System PDFCedricNo ratings yet

- Business Communication - EnG301 Power Point Slides Lecture 14Document14 pagesBusiness Communication - EnG301 Power Point Slides Lecture 14Friti FritiNo ratings yet

- Verb be (singular): he, she, it grammar activityDocument7 pagesVerb be (singular): he, she, it grammar activityGeorge ZarpateNo ratings yet

- Which vs. ThatDocument4 pagesWhich vs. ThatÁngel Valdebenito VerdugoNo ratings yet

- Personal Pronouns GermanDocument7 pagesPersonal Pronouns Germanvarungupta1988No ratings yet

- EPP Infodump VersionDocument16 pagesEPP Infodump Versionearthalla yaNo ratings yet

- Eyes OpenDocument1 pageEyes OpenCelia Cunha100% (1)

- Unit 2 Extra PracticeDocument5 pagesUnit 2 Extra PracticeVictoria VmyburghNo ratings yet

- Social Media For Improving Students' English Quality in Millennial EraDocument8 pagesSocial Media For Improving Students' English Quality in Millennial Erawolan hariyantoNo ratings yet

- 000 Sap English For Acop AccDocument27 pages000 Sap English For Acop AccresigjeflinNo ratings yet

- A. Answer These Following Questions. (5 PTS) : Morphology Test 2Document2 pagesA. Answer These Following Questions. (5 PTS) : Morphology Test 2Hưng NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Comprobante Cuenta Subcuenta Debito y CreditoDocument1,081 pagesComprobante Cuenta Subcuenta Debito y CreditoDaniel OrjuelaNo ratings yet

- FONTSDocument9 pagesFONTSSalveigh C. TacleonNo ratings yet

- An American and Vietnamese cross cultural study on refusing an inivtation.Nguyễn Thanh Loan.QHF1E2006Document72 pagesAn American and Vietnamese cross cultural study on refusing an inivtation.Nguyễn Thanh Loan.QHF1E2006Kavic88% (8)

- DA & Pragmatics Course OutlineDocument4 pagesDA & Pragmatics Course Outlineamenmes22No ratings yet

- Lec 7Document29 pagesLec 7ARCHANANo ratings yet

- Master The SAT by Brian R. McElroy - How To Study and Prepare For The SAT College Entrance ExamDocument12 pagesMaster The SAT by Brian R. McElroy - How To Study and Prepare For The SAT College Entrance ExamanonymousxyzNo ratings yet

- Lesson#2 Elements and Types of CommunicationDocument24 pagesLesson#2 Elements and Types of CommunicationAlie Lee GeolagaNo ratings yet

- Kurdish EFL Students' Attitudes Towards Teachers' Use of Code SwitchingDocument32 pagesKurdish EFL Students' Attitudes Towards Teachers' Use of Code SwitchingArazoo Atta HamasharifNo ratings yet

- TEFL Mixed ability class techniquesDocument12 pagesTEFL Mixed ability class techniquesAin SyafiqahNo ratings yet

- Plural TheoryDocument6 pagesPlural TheoryCristina StepanNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 Teaching Reading: ObjectivesDocument16 pagesLesson 3 Teaching Reading: Objectivesmaryrose condesNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of EnglishDocument12 pagesA Brief History of EnglishJN Ris100% (1)

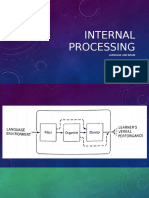

- Internal ProcessingDocument15 pagesInternal Processingmia septianiNo ratings yet

- Alesina Et Al. (2003) - FractionalizationDocument40 pagesAlesina Et Al. (2003) - FractionalizationSamuel Mc QuhaeNo ratings yet

- Activity Sheet in English 6: Quarter 1 Week 6-Day 4Document7 pagesActivity Sheet in English 6: Quarter 1 Week 6-Day 4NOEMI VALLARTANo ratings yet

- A Magical ButterflyDocument3 pagesA Magical ButterflyДаша СукачNo ratings yet