Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Party Systems

Uploaded by

Mary KishimbaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Party Systems

Uploaded by

Mary KishimbaCopyright:

Available Formats

Party Systems Party systems dominate politics in Britain. In "Party and Party Systems", G.

Sartori describes a party system as:

"the system of interactions resulting from inter-party competition".

To develop this idea, within Britain the party system essentially means the way the political parties of the day interact with one another within the politically competitive nature of Westminster and beyond. A number of different types of party systems have been identified: One-party system: a one-party system cannot produce a political system as we would identify it in Britain. One party cannot produce any other system other than autocratic/dictatorial power. A state where one party rules would include the remaining communist states of the world (Cuba, North Korea and China), and Iraq (where the ruling party is the Baath Party). The old Soviet union was a one party state. One of the more common features of a one-party state is that the position of the ruling party is guaranteed in a constitution and all forms of political opposition are banned by law. The ruling party controls all aspects of life within that state. The belief that a ruling party is all important to a state came from Lenin who believed that only one party - the Communists - could take the workers to their ultimate destiny and that the involvement of other parties would hinder this progress. Two-party system: as the title indicates, this is a state in which just two parties dominate. Other parties might exist but they have no political importance. America has the most obvious two-party political system with the Republicans and Democrats dominating the political scene. For the system to work, one of the parties must obtain a sufficient working majority after an election and it must be in a position to be able to govern without the support from the other party. A rotation of power is expected in this system. The victory of George W Bush in the November 2000 election, fulfils this aspect of the definition. The two-party system presents the voter with a simple choice and it is believed that the system promotes political moderation as the incumbent party must be able to appeal to the floating voters within that country. Those who do not support the system claim that it leads to unnecessary policy reversals if a party loses a election as the newly elected government seeks to impose its mark on the country that has just elected it to power. Such sweeping reversals, it is claimed, cannot benefit the state in the short and long term. The multi-party system: as the title suggests, this is a system where more than two parties have some impact in a states political life. Though the Labour Party

has a very healthy majority in Westminster, its power in Scotland is reasonably well balanced by the power of the SNP (Scots Nationalist Party); in Wales within the devolutionary structure, it is balanced by Plaid Cymru; in Northern Ireland by the various Unionists groups and Sein Fein. Within Westminster, the Tories and the Liberal Democrats provide a healthy political rivalry. Sartori defines a multi-party system as one where no party can guarantee an absolute majority. In theory, the Labour Party, regardless of its current parliamentary majority, could lose the next general election in Britain in 2006. Even its current majority of 167 cannot guarantee electoral victory in the future. A multi-party system can lead to a coalition government as Germany and Italy have experienced. In Germany these have provided reasonably stable governments and a successful coalition can introduce an effective system of checks and balances on the government that can promote political moderation. Also many policy decisions take into account all views and interests. In Italy, coalition governments have not been a success; many have lasted less than one year. In Israel, recent governments have relied on the support of extreme minority groups to form a coalition government and this has created its own problems with such support being withdrawn on a whim or if those extreme parties feel that their own specific views are not being given enough support. Dominant-party system: this is different from a one-party system. A party is quite capable within the political structure of a state, to become dominant to such an extent that victory at elections is considered a formality. This was the case under the Conservative governments of Margaret Thatcher and John Major. For 18 years (1979 to 1997), one party dominated politics in Britain. In theory, the Conservatives could have lost any election during these 18 years. But such was the disarray of the opposition parties - especially Labour - that electoral victory was all but guaranteed. The elections of the 1980s and 1990s were fought with competition from other parties - hence there can be no comparison with a one-party state. During an extended stay in power, a dominant party can shape society through its policies. During the Thatcher era, health, education, the state ownership of industry etc. were all massively changed and re-shaped. Society changed as a result of these political changes and this can only be done by a party having an extended stay in office. Other features of a dominant system are: the party in power becomes complacent and sees that its position in power is guaranteed. Such political arrogance is seen as one of the reasons for the publics overwhelming rejection of the Conservatives in 1997. the difference between the party in power and the state loses its distinction. When both appear to merge, an unhealthy relationship develops whereby the

states machinery of carrying out government policy is seen as being done automatically and where senior state officials are rewarded by the party in power. This scenario overshadowed the Thatcher governments when the Civil Service was seen as a mere rubber stamp of government policy to do as it was told and senior Civil Servants were suitably rewarded in the Honours lists. An era of a dominant party is also an era when opposition parties are in total disarray. This was true during the Conservatives domination of Britain in the 1980s. Once the Labour Party started to strengthen in the 1990s and internal problems were resolved, the whole issue of a dominant party was threatened leading to the defeat of the Conservatives in 1997. It would be fair to conclude that Britain has a dominant-party system now. Within certain criteria, the Labour government with its near 180 majority in Westminster, has the freedom to do politically what it likes. The powers devolved to the regions were restrained by the simple fact that Westminster is still the major purse-holder of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, thereby not giving these three regions the freedom they believe they need to be truly devolved governments.

TYPES OF PARTY SYSTEM*

JEAN BLONDEL From Peter Mair (ed.) The West European Party System (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990), pp. 302-310.

If undertaken on a world basis, the analysis of party svstems would require a consideration of the number of parties, of their strength, of their place on the ideological spectrum, of the nature of their support, and of their organization and type of leadership. In the context of Western liberal democracies, it is possible to limit the analysis to the first three of these characteristics. With very few exceptions, Western parties can be deemed to be of the 'legitimate' mass type and to have a regularized system of leadership selection. Charismatic leadership is exceptional and, at the other extreme, Communist parties are becoming increasingly similar to other parties. Western parties appeal nationally to the electorate by trying to put across a general image; differences are more to be found in the type of image than in the structural characteristics of the organization. I. Number of Parties in the System Two-party systems are rarely defined operationally. Yet, among Western democracies, four groups are clearly discernible (see Table 22. 1). Five countries give on average more than go per cent of their votes to the two major parties. Second, five countries give between 75 and

8o per cent of their votes to the two major parties (though Belgium fell markedly below this level at the last election). In six countries, the two major parties obtain about two-thirds of the votes (though Holland is somewhat different, as we shall see). Finally, three countries give about half their votes to the two major parties, though, for the last two elections, France would have to be moved from the fourth to the third category: but as the French situation may well alter again after the end of the de Gaulle era, it is probably more realistic to draw conclusions from the average of the whole post-war period than merely from developments in the1960s.

TABLE 22. 1. Average Two-Party Vote, 1945-66 (percentage) United States New Zealand Australia United Kingdom Austria

99 95 93 92 89

West Germany Luxemburg Canada Belgium Eire

80 80 79 78 75

Denmark Sweden Norway Italy

66 66 64 64

Iceland Holland

62 62

Switzerland France Finland

50 50 49

Countries belonging to the first group can be defined as two-party systems, though there is some ambiguity in the cases of Australia and Austria; in both these countries some governments depended for their constitution or maintenance on the support of more than one party. The five countries of the second group constitute the three-party systems, Germany having arrived at this status as a result of the operation of the electoral system as well as of the Adenauer tactics. The nine countries of the last two groups are the genuine multiparty systems, in which four, five, or even six parties play a significant part in the political process.

2. Strength of Parties

Little has to be said about countries of the first group, in which go per cent or more of the electors vote for, and go per cent or more of the seats are distributed between, the two major parties. It is interesting to note that discrepancies in strength between the two major parties are remarkably small, at least if averaged over the post-war period. While it could in theory be the case that one party might be permanently much larger than the other, no two-party system (i.e., no system in which the two parties obtain 89 per cent of the votes) gives to the larger of the two parties a permanent premium of over i o per cerit of its own electorate. Despite differences in social structure, for instance, between the United States, the United Kingdom, and Austria, the electorate distributes its preferences fairly evenly between the two parties. Although it cannot be stated with assurance that such a situation cannot exist in any type of social system (there are indeed examples of uneven distribution of party support among two-party systems outside Western democracies), it seems possible to hypothesize, in the absence of contrary evidence, that, in Western democracies, two party systems show a tendency towards a relative equilibrium between the two parties. Countries in the three-party system group also share several characteristics. First, disparities in strength between the two larger parties are generally much greater than among countries in

the first group. They seem structural in that the swing of the pendulum does not, as among countries of the first group, diminish the gap, even if one considers a fairly long period: the average percentage point difference between the two major parties among the five countries of the first group is only 1.6 if all post-war elections are taken into account; it is 10.5 in countries of the second group (excluding Luxemburg where data for all elections were not available) [see Table 22.2]. The often stressed phenomenon of the German SPD, which has not been able to achieve equality of strength with the CDU, is thus a general phenomenon among countries of this group. It can therefore be stated that in countries in which about 8o per cent of the votes go to two parties the distribution of the support tends to be uneven. TABLE22.2. Average Strength of the Two Major Parties in Two- and Two-and-a-half Party Systems (percentage votes cast) Two-party systems Two-and-a-half party systems Difference Difference United States New Zealand 49-50= 48-47= 1 1 Germany Canada 45-35= 36-43= 10 7

Australia United 47-46= Kingdom Austria 45-47= 46-43=

1 2 3

Belgium Eire

43-35= 46-29=

8 17

Mean disparity between the two major parties=1.6

Mean disparity between the two major parties=10.5

Three-party systems also have another, and converse, characteristic. They all have two major parties and a much smaller third party. While it would seem theoretically possible for threeparty systems to exist in which all three significant parties were of about equal size, there are in fact no three-party systems of this kind among Western democracies: all the three-party systems are in the second group; all systems of the third group have more than three significant parties. It can thus be stated that, while theoretically possible, a genuine threeparty system is not a likely type of system among Western democracies: countries of the second group should therefore be more strictly labelled as 'two-and-a-half-party systems'. It may indeed be permissible to add, after considering the evolution of party systems, particularly in the early part of the twentieth century, that genuine three-party systems do not normally occur because they are essentially transitional, thus unstable, forms of party

systems. The situation arising out of the 1965 Belgian election was thus of particular interest, since the upsurge of the Liberal party and the decline of the two major parties was such that Belgium appeared to have moved into the exceptional and seemingly transitional position of a 'genuine' three party system. If the proposition advanced earlier is correct, it would seem that in the next few years Belgium will move to one of three types of further changes. The Liberals could return to their 'normal' position of small party; they could displace one of the two major parties (an unprecedented development in Western Europe since all the movements happened in the other direction); a split could occur among the supporters of one or both of the major parties and Belgium might move from the second group of countries (two-and-a-half party systems) to the third or fourth (multiparty systems). From the experience of other Western democracies the first and third of these three outcomes appears more probable than the maintenance of a genuine three-party system. We included Holland among the countries which constituted the third group, composed of those countries in which the two largest parties obtained about two-thirds of the votes of the electorate. But if we consider the relative strength of the two major parties, the five other countries of the group differ markedly from Holland, in that they have one very large party, which might be defined as dominant as it obtains about 40 per cent of the electorate and generally gains about twice as many votes as the second party. In fact, in both Norway and

Sweden, the mechanics of the electoral system have sometimes enabled this dominant party to obtain the absolute majority of seats in the Chamber. But these countries are at the same time multiparty systems as they all have four or five significant (and often well-structured) parties playing a crucial role in the operation of the political system. Four of the five Scandinavian countries are included in this group (the fifth being Italy), though in Iceland the dominant party is not the Socialist but the Conservative (Independence) party. The Fifth Republic, at least under de Gaulle, appears to be moving towards this pattern of party system, though the characteristics of the Gaullist party are such that it seems unreasonable to predict that the present party configuration is likely to survive de Gaulle. Thus, alongside two-party systems and two-and-half-party systems, the third group should be defined, not so much as a multiparty system in which two parties obtain about two-thirds of the votes of the electorate, but as a multiparty system with a dominant party which obtains about two-fifths and less than half of the votes. Finally, the last four countries (if Holland is included and France maintained in the group in the view of the past and possible future performance of that country) constitute the genuine multiparty systems: they have no dominant body and indeed seem to show a pattern of political behaviour in which three or four parties are equally well placed to combine or form coalitions. Recent electoral movements in Holland appear to bring that country gradually nearer towards this model: the slow decline of the Labour party and the patterns of governmental formation have tended to conform fairly closely to those which have been

customary of Finland.

3. Ideological Spectrum and Party Strength Western democracies can therefore be divided into four groups, if both numbers and strengths are taken into account: five are in the two-party system group, five in the two-anda-half-party system group, are in the group of multiparty systems with dominant party, and four in the group of multiparty systems without dominant party. But the party system can only wholly be defined if we take into account the position of parties on the ideological spectrum, particularly when the system does not have a 'symmetrical' character. Even in Western democracies, parties are difficult to categorize accurately. The United States and Eire always had parties which do not fit in any easily recognizable typology. The French Gaullists are not ordinary Conservatives, though they may have to be lumped with Conservatives for comparative purposes. The other multi-party system countries all have parties of a somewhat peculiar type, such as the two Conservative partles in Holland, the Swedish party in Finland, and the party of the Peasants, Artisans, and Bourgeois in Switzerland. In all these cases, certain rough approximations have had to be made. Table 22.3 shows the panorama of party strengths within the ideological spectrum. Group I, except for the United States, is fairly homogeneous: the four other countries in the group have a large Socialist party and a large Conservative or Christian party, together with a small other group, whose position in the centre is perhaps sometimes problematic. Countries of group 2 have two types of party systems: Belgium, Germany, and Luxemburg resemble countries of group I, except that the centre party is stronger and, as we noted earlier, this increased strength is mainly at the expense of one only of the two major parties (in fact the Socialist party). The other two countries of the group (Canada and Eire) are different: the small party is not the centre, but the left-wing, party and, probably not quite accidentally, the right-wing party Is not Christian but Conservative. In the early part of the twentieth century, it would probably have been argued that both these countries were still in a transitional stage: Canada has a party system not unlike that of Britain in igo6. But it must by now be recognized both that the two- and -a-h alf- party system is stable (Belgium and Germany have had for long periods the British party system of the 192os and do not appear to move further towards a two-party system) and that the two-and-a-half-party system is stable even if the left-wing party is the small party. Neither the Irish Labour party nor the Canadian NDP appear to be in a position to overtake the centre party in the near future: their position of small party seems stable. The reasons for the stability of the Canadian model of two-and-ahalf-party system are probably to be found along lines similar to those which account for the stability of the American parties, which have remained in existence despite earlier predictions to the contrary.

Two types, and not more than two types, of multiparty systems with a dominant party can be found. Three Scandinavian countries have a dominant Socialist party; Iceland and Italy have a dominant Conservative or Christian party. In the latter two cases, we encounter for the first time countries with a really large Communist party. In Iceland and Italy (as in Finland and even France) the Communist party remained fairly stable throughout the whole period; the Socialist party is therefore correspondingly weak and the left is divided; as is well known, the converse occurs in Norway, Denmark, and Sweden. In these three countries, though the agrarian party is not placed symmetrically in relation to the Communists on the political spectrum, it probably plays the same divisive part. The absence of religious divisions might have led one to expect the three Scandinavian countries which do not have a large Communist party to have two-and-a-half-party systems, but the apparent feelings of identity of the agricultural community have created permanent cleavages on the right which have produced a party system in many ways 'symmetrical' to that of Iceland and Italy. Countries of the fourth group have no dominant party: party strengths are therefore fairly

evenly spread across the ideological spectrum, though Holland and Switzerland, with weak Communist parties, display somewhat less spread than France and Finland. This latter country combines the splintering characteristics of left and right of the Scandinavian countries: the divisions of Iceland are superimposed on those of Sweden. There are thus six types of party systems in Western democracies. At one extreme are the broadly based parties of the two-party system countries: the United States is the most perfect case of this type, but four other countries closely approximate this model and they only diverge inasmuch as they have a small centre party and are divided ideologically between conservatives and socialists. At the other extreme, the votes of the electors are spread fairly evenly, in groups of not much more than 25 per cent and in many cases much less than 25 per cent over the whole ideological spectrum, as in Holland, Switzerland, France, and Finland. Between these two poles, one finds four types of party systems: five countries have two-and-a-half-party systems: among them, three have a smaller centre party, while the other two have a smaller left-wing party. The five remaining countries are multiparty systems with 1.Types of Party Systems2. Factors that influence pluraristic party systems3. Issues related to Romanian party systemTypes of Party Systems Joseph Lapalombara and Weiner classified accourding to 1.thenumber pf parties; 2.internal characteristics of parties(ideology etc); 3.theway political power is held by them. They identified 3 types of political systems according to these: By the nr of parties: 1. The non-party political systems

there are situations whereparties do not form, or are repressed once formed. Parties aredeliberately prevented to form or continue to exist.Ex: Authoritarian regimesdominate by military or civil-bearucratic rule that deny a legitimate place for parties in thepolitical stage.(it is difficult to function without parties) 2. Competitive Political Systems where theoretically and legallyparties are accepted, are desired and where parties once inpower may be then out of power and may then be in. Two-party system.Multiparty system. 3.Non-competitive Party Systems a. One party authoritarian system classicalauthoritarian system, based on ideology, oneparty, dominating from more than a hegemonicposition. Members of oposition are consideredtraitors. b. One party pluralistic authoritarian would like toabsorb opposition not destroy it: Mexico untilrecently c. One party totalitarian system the ideology isimportant but here the one party is destroying itsopposition, the other are out of the law. TOTALDOMINATION. The one party becomes the stateitself.ex: National Socialist Party under nazi regime,Hitler; Communist Party in Soviet Union; East-Euregimes until 70s; North Vietnam, Cuba.For SELF-JUSTIFICATION they need enemies-often outside. Criteria needed for a real democracy not a pseudo-one like popular democracies in post ww

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Vacancy UNA Tanzania1Document4 pagesVacancy UNA Tanzania1Mary KishimbaNo ratings yet

- ps335 Seminar PaperDocument6 pagesps335 Seminar PaperMary KishimbaNo ratings yet

- Crises and Consequences in Political DevelopmentDocument4 pagesCrises and Consequences in Political DevelopmentMary KishimbaNo ratings yet

- Modernization TheoryDocument11 pagesModernization TheoryMary KishimbaNo ratings yet

- Problem Analysis and LFADocument9 pagesProblem Analysis and LFAMary KishimbaNo ratings yet

- Kenya Law Making ProcessDocument4 pagesKenya Law Making ProcessMary Kishimba75% (4)

- Responsibility To ProtectDocument39 pagesResponsibility To ProtectMary KishimbaNo ratings yet

- Abdalla Amr (2009) Understanding C.R. SIPABIODocument10 pagesAbdalla Amr (2009) Understanding C.R. SIPABIOMary Kishimba100% (1)

- How Change Happens: Interdisciplinary Perspectives For Human DevelopmentDocument59 pagesHow Change Happens: Interdisciplinary Perspectives For Human DevelopmentOxfam100% (1)

- Modernization TheoryDocument11 pagesModernization TheoryMary KishimbaNo ratings yet

- Brock Utne 92IJPSDocument13 pagesBrock Utne 92IJPSMary KishimbaNo ratings yet

- Convencao de Viena de 1978 Sobre Sucessao de Estados em Materia de TratadosDocument24 pagesConvencao de Viena de 1978 Sobre Sucessao de Estados em Materia de Tratadosnunomm25No ratings yet

- Gacaca CourtsDocument16 pagesGacaca CourtsMary KishimbaNo ratings yet

- Mary Kishimba and Theresia Tongora R2PDocument9 pagesMary Kishimba and Theresia Tongora R2PMary KishimbaNo ratings yet

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- UntitledDocument3 pagesUntitledMary KishimbaNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument3 pagesUntitledMary KishimbaNo ratings yet

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Modernization TheoryDocument11 pagesModernization TheoryMary KishimbaNo ratings yet

- Sadc - Guidebook For Regional IntegrationDocument196 pagesSadc - Guidebook For Regional IntegrationMary Kishimba0% (1)

- Scarcity and SurfeitDocument37 pagesScarcity and SurfeitMary KishimbaNo ratings yet

- IR Theory As Politics, International Politics As Theory: A Nigerian Case Study Emily Meierding University of ChicagoDocument17 pagesIR Theory As Politics, International Politics As Theory: A Nigerian Case Study Emily Meierding University of ChicagoMary KishimbaNo ratings yet

- Coastal Ecology Lecture 19th OctDocument20 pagesCoastal Ecology Lecture 19th OctMary KishimbaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Vectors in Mat LabDocument6 pagesIntroduction To Vectors in Mat LabMary KishimbaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Clark SubpoenaDocument11 pagesClark SubpoenaDaily KosNo ratings yet

- Emilio Famy Aguinaldo (22 March 1869 - 6 February 1964) Is Officially Recognized As TheDocument18 pagesEmilio Famy Aguinaldo (22 March 1869 - 6 February 1964) Is Officially Recognized As TheDeanne BurcaNo ratings yet

- Are We Good or EvilDocument1 pageAre We Good or EvilJoshua VázquezNo ratings yet

- PPG Reportings 9Document36 pagesPPG Reportings 9Jhoncel Auza DegayoNo ratings yet

- S2 British Studies SummaryDocument2 pagesS2 British Studies SummaryRAYEN NOUARNo ratings yet

- Soal Sas Bahasa Inggris Kelas 4Document3 pagesSoal Sas Bahasa Inggris Kelas 4Sania JanahNo ratings yet

- The Dead Speak - Black Consciousness Play by Andile MafrikaDocument2 pagesThe Dead Speak - Black Consciousness Play by Andile MafrikaThandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

- SSG AccomplishmentReportDocument7 pagesSSG AccomplishmentReportMhyke Vincent PanisNo ratings yet

- Un Quiz Bee-2022Document2 pagesUn Quiz Bee-2022Jackie AlmerolNo ratings yet

- TrumbullOH2008 General AbstractDocument4,014 pagesTrumbullOH2008 General AbstractJacob Alperin-SheriffNo ratings yet

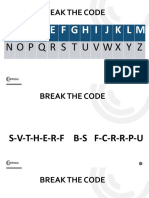

- Break The Code: Abcdefghij KLMDocument62 pagesBreak The Code: Abcdefghij KLMJoycelyn Villavicencio100% (1)

- My Presidential SpeechDocument2 pagesMy Presidential Speechjasmine lopezNo ratings yet

- Who Wants To Be A Great Power?: by Lawrence FreedmanDocument12 pagesWho Wants To Be A Great Power?: by Lawrence FreedmansdfghNo ratings yet

- Taller 1 InglesDocument4 pagesTaller 1 InglesDeisy Paola GarciaNo ratings yet

- 2020-09-24 Calvert County TimesDocument24 pages2020-09-24 Calvert County TimesSouthern Maryland OnlineNo ratings yet

- Sample Minutes of Post QuaDocument1 pageSample Minutes of Post QuaARMA G. TANGAPANo ratings yet

- STORRE-Television-national Identity-And-The-Public-Sphere-A-Comparative-StudDocument337 pagesSTORRE-Television-national Identity-And-The-Public-Sphere-A-Comparative-StudFernando Molinas NavarroNo ratings yet

- Arab League Summit 2022 in AlgeriaDocument3 pagesArab League Summit 2022 in AlgeriaNouhad SalimNo ratings yet

- Contribution PrintnsrDocument29 pagesContribution PrintnsrcontactajaysidharNo ratings yet

- Hiroaki Kuromiya - The Donbas-The Last Frontier of EuropeDocument25 pagesHiroaki Kuromiya - The Donbas-The Last Frontier of EuropearinaNo ratings yet

- Advisory Opinion To The Attorney General Re: Adult Personal Use of MarijuanaDocument30 pagesAdvisory Opinion To The Attorney General Re: Adult Personal Use of MarijuanaCato InstituteNo ratings yet

- The Din of Silence - Reconstructing The Keezhvenmani Dalit Massacre of 1968Document27 pagesThe Din of Silence - Reconstructing The Keezhvenmani Dalit Massacre of 1968ramachandranNo ratings yet

- 5 6309812698813038801 PDFDocument64 pages5 6309812698813038801 PDFHarsh BansalNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 1 South African Constitutional Law inDocument39 pagesCHAPTER 1 South African Constitutional Law inMalvin D GarabhaNo ratings yet

- The Hill We Climb Amanda GormanDocument3 pagesThe Hill We Climb Amanda GormanDS RoseNo ratings yet

- Ruth Wodak - The Politics of Fear - What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean-Sage Publications (2015)Document309 pagesRuth Wodak - The Politics of Fear - What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean-Sage Publications (2015)BEeNaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 Activity 2Document1 pageLesson 3 Activity 2Mae camila BattungNo ratings yet

- India: Who Are The Most Underrated Indians Ever?: 100+ AnswersDocument17 pagesIndia: Who Are The Most Underrated Indians Ever?: 100+ AnswersRaja SimmanNo ratings yet

- Q2 Module 2 The LegislativeDocument2 pagesQ2 Module 2 The LegislativeMarc NillasNo ratings yet

- An Economist's Guide To The World in 2050Document11 pagesAn Economist's Guide To The World in 2050James YoungNo ratings yet