Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Classroom Art Talk - How Discourse Shapes Teaching and Learning in

Uploaded by

Yuni IsaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Classroom Art Talk - How Discourse Shapes Teaching and Learning in

Uploaded by

Yuni IsaCopyright:

Available Formats

Marilyn Zurmuehlen Working Papers in Art Education

Volume 2000 | Issue 1 Article 1

1-1-2000

Classroom Art Talk: How Discourse Shapes Teaching and Learning in a High School Art Classroom

Teresa L. Cotner

Recommended Citation

Cotner, Teresa L. (2000) "Classroom Art Talk: How Discourse Shapes Teaching and Learning in a High School Art Classroom," Marilyn Zurmuehlen Working Papers in Art Education: Vol. 2000: Iss. 1, Article 1. Available at: http://ir.uiowa.edu/mzwp/vol2000/iss1/1

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Teaching and Learning at Iowa Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marilyn Zurmuehlen Working Papers in Art Education by an authorized administrator of Iowa Research Online. For more information, please contact lib-ir@uiowa.edu.

Cotner Classroom Art Talk Cotner: Classroom Art Talk: How Discourse Shapes Teaching and Learning in

Dissertation Abstract

In Working Papers in Art Education (NAEA-Thunder-McGuire)

and

In ERIC Database

Classroom Art Talk: How Discourse Shapes Teaching and Learning

in a High School Art Classroom

Teresa L. Cotner

Stanford University School of Education

May 2000

http://ir.uiowa.edu/mzwp/vol2000/iss1/1

Cotner Classroom Marilyn Zurmuehlen Working Papers in Art Education, Vol. 2000 [2000], Iss. 1, Art. 1 Art Talk

Summary of the Problem This study of classroom art talk, CAT, responds to curricular reform mandates for art education that have gained increasing acceptance over the last thirty years. These mandates recommend that art teachers include the language-based domains of art, namely, art criticism, art history, and aesthetics, in studio arts curriculum. Today, arts curricula at national, state, and local levels call for instruction in art criticism, art history, aesthetics, and studio practice.1 The language-based domains of art present new challenges to art teachers and their students, who have traditionally focused on studio practices. To date, high school art teachers, in comparison to junior high school and elementary teachers, have participated very little in professional development training in teaching the language-based domains of art (Wilson, 1997, pp. 166-67). Currently, little is known about the extent to which high school art teachers teach in the language-based domains of art, nor about the role talk plays in teaching and learning in the language-based and studio domains of art. This is an alarming deficit given that as of 1998 in the United States, 32 states recommend visual arts as a requirement for high school graduation (NAEA News, April, 1998). Aims of the Study The overarching aim of this study is to examine CAT in order to better understand what high school teachers and students have to say in matters related to art criticism, art history, aesthetics, and studio practice as a part of art classroom pedagogy; and by inference, to flesh out how CAT shapes teaching and learning in art. The three aims of this study are: 1. To describe and analyze the contexts in which CAT occurs. 2. To describe and analyze the patterns of speech and the terminology of CAT. 3. To describe and analyze how the social and curricular levels of CAT shape teaching and learning. The first aim invites description and analysis of the character, including frequency and duration, of talk under typical circumstances in a high school art classroom. I identify three contexts of CAT: 1. teacher-student whole class 2. teacher-student one-on-one (and impromptu small groups) 3. student-student one-on-one (and impromptu small groups). In each context of CAT, teacher and students attend to ideas that are relevant to the four domains. Therefore, CAT can be thought of as, Talking Art Criticism (C), Talking Art History (H), Talking Aesthetics (A), and Talking Studio Practice (S).2 Talking Art Criticism refers to talk that pertains

1

Eisner, E. (1988). The role of discipline-based art education in Americas schools . Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Trust; National Standards for Arts Education: What Every Young American Should Know and Be Able to Do in the Arts (1994) Reston, VA Music Educators National Conference; Visual and Performing Arts Framework for California Public Schools: Kindergarten Through Grade Twelve (1996) Sacramento, California Department of Education. 2 In this paper, I use the terms Criticism, History, Aesthetics, and Studio (CHAS) for purposes of brevity and clarity. The Visual and Performing Arts Frameworks for California Public Schools Kindergarten Through Grade Twelve, (1996) uses Artistic Perception, Historical and Cultural Context, Aesthetic Valuing, and Creative

http://ir.uiowa.edu/mzwp/vol2000/iss1/1

Cotner Classroom Art Talk Cotner: Classroom Art Talk: How Discourse Shapes Teaching and Learning in

to perception, the ability to synthesize and assess sensory information in art such as light, color, texture and composition. Talking Art History is to speak of the cultural and historical contexts of art including biographical information about artists and about the situatedness of the style of a particular work of art comparatively and chronologically with other art styles. Talking Aesthetics is a philosophical discourse about art that analyzes the very nature of art and the characteristics of aesthetic experience. Aesthetics is defined in the Random House College Dictionary (1982) as the study of the qualities perceived in works of art, with a view to the abstraction of principles; and the study of the mind and emotions in relation to the sense of beauty (p.22). Talking Studio Practices refers to talk about creative expression through various techniques and procedures using arts media. My second aim invites description and analysis of the unique qualities of the language used to talk about art in the art classroomCAT as dialectic or vernacular. Notably, Lemkes study of high school science discourse, Talking Science (1990) helped focus my attention on the patterns and specialized terminology of CAT. Lemke suggests that specialistsincluding teachers use language in ways that are particularly well suited to their discipline, be it music or physics. The assumption here is that to the extent to which people use the same patterns and specialized terminologyin a subject discipline and in culture or societythey are likely to understand each others intended meanings. A related and equally important assumption of mine is based on the Sapir/Whorf hypothesis of linguistic determinism, or linguistic conditioning. This theory holds that the language we speak shapes perception. According to the Sapir/Whorf hypothesis, language is likely to shape how students think about art. My third aim invites description and analysis of the social and curricular levels of CAT. Cazden identifies the functions of classroom discourse as the language of curriculum, the language of control, and the language of personal identity or the propositional, social, and expressive functions (Cazden, 1988, p.3). In teacher and student discourse about art, the propositional can be understood as curricular (talk about art) and the social and expressive can be understood as social, how teacher and student talk establishes and maintains their roles in the social arena of the classroom. Thus, in this study, teacher and student CAT is described and analyzed as communication at the curricular and social level. Given the paucity of research in this area of art education, this study seeks to illuminate a phenomenon, CAT, that is integral to teaching, and by inference, given the linguistic theoretical framework, to illuminate how talk might influence learning. Site and Participants Miramar High Schools students backgrounds range from working class to upper middle class families. Mr. R. is considered a good teacher. He teaches printmaking, design, and art history at Miramar. He makes and collects art. He has taught high school art for 35 years. He is well respected by his principal and other art teachers at his school and in his district. He is a popular teacher with students. Printmaking is a an introductory level class in which students work with linoleum block printing and silk screen.

Expression. The Role of Discipline-Based Art Education in American Schools (1988) uses Criticism, History and Culture, Aesthetics, and Production.

http://ir.uiowa.edu/mzwp/vol2000/iss1/1

Cotner Classroom Marilyn Zurmuehlen Working Papers in Art Education, Vol. 2000 [2000], Iss. 1, Art. 1 Art Talk

Mr. R.s printmaking students range from 9th to 12th graders. They vary in how much art theyve had before this class and in how interested they are in art. Printmaking 1 had one group of about 30 students in the fall semester and another group of the same size in the spring semester. Classes at Miramar meet on a rotating schedule, every class meets every other day for 100 minutes. Methodology Data Collection I spent approximately 6 hours a week as participant observer in the printmaking classroom, including classtime and about a half hour before and after class, twice a week. This totals approximately 216 hours in the two semesters of observation. I recorded a total of 45 hours of naturally occurring CAT. I interviewed Mr. R. and a total of 11 of his students throughout the year. I interviewed five groups of 3-4 students together, at different times throughout the year. I talked with students in class throughout the year. I photographed student artwork, finished and in progress. I videotaped one group interview and two class sessions. Data Analysis I selected an episode of CAT in Contexts 1 and 2, and several, which were shorted episodes, in Context 3 for analysis in the body chapters of my paper. Context 1 is analyzed in Chapter 3, Context 2 in Chapter 4, and Context 3 in Chapter 5. Episodes were selected for analysis based on their being representative of typical CAT in Mr. R.s Printmaking 1 class, and for their being particularly illustrative of how CAT shapes teaching and learning. In Chapters 3-5, episodes of talk are introduced with a description of the particular setting in which they happened. I then describe the social and the curricular levels of the discourse. I use a coding system that I developed for analyzing CAT to micro analyze just a few lines from each episode (see examples p.11), which enabled me to look at examples of talking art criticism, art history, aethetics, and studio practice as direct references and also as indirect, tangential, and ancillary. Finding 1. CAT occurs in three distinct and very different contexts. Context 1, teacher-student whole-class, focuses primarily on the how and why of printmaking that students will do or are in the process of doing. It can last from 30 seconds to 85 minutes. The curricular level of Context 1 CAT is rich and comprehensive. The social level is filled with implicit expressions of credibility and of power dynamics of speakers in their roles in the classroom. For example, in the episode of Context 1 CAT analyzed in Chapter 3, Mr. R. shares his extensive background and knowledge of art and in the same words, establishes credibility for himself as teacher. When questioning something Mr. R. had said, his student

http://ir.uiowa.edu/mzwp/vol2000/iss1/1

Cotner Classroom Art Talk Cotner: Classroom Art Talk: How Discourse Shapes Teaching and Learning in

Mike makes a point of using art vocabulary that Mr. R. had introduced, and in doing so, establishes credibility for himself as student and challenges Mr. R.s credibility. Context 2, teacher-student one-on-one (and impromptu small groups), focused primarily on critique of individual student artwork, usually artwork in progress. It can last 30 seconds to 10 minutes. As in Context 1, the curricular level is rich and comprehensive. The social level attends to teacher and student implicitly establishing credibility through their knowledge of art, and negotiating the extent of power each has in assessing and making final decisions concerning the students artwork. For example, in the episode of Context 2 CAT analyzed in Chapter 4, Mr. R.s critiques attend to a vast and varied collection of components and nuances particular to visual art within the context of his student Normans work. This is the curricular level of his talk. These same words, on the social level, are also peppered with could, may, probably, and you got two choices, which implicitly communicate the extent to which Mr. R.s comments can be understood as suggestions or directives. His student Normans critiques are comparatively less vast and less rich in art contentthe curricular levelbut are also peppered with well actually and its supposed to be in his attempts to establish his own credibility and establish the extent of his authority, or power, in final decisions concerning his own artwork, the social level. Context 3, student-student one-on-one (and impromptu small groups), focuses on both the how and why of the printmaking projects and on individual students artwork. It ranges from just 2 to 36 exchanges. In comparison to Contexts 1 and 2, the talk is brief, less rich, and less comprehensive on the curricular level. Students appear to avoid using art terminology, for example using the common term frame instead of mat board, which means more than just a frame. On the social level, this art talk communicates strong adherence to camaraderie. In the episodes examined in Chapter 5, this camaraderie falls under three headings, Liaisons Interpretations, Stick-Togetherness, and Compliments. My descriptions of these three contexts of CAT offer a structure and suggest the facility of talk about art that can help teachers to incorporate talk in their art pedagogy and curriculum more effectively. Finding 2. CAT is abundant. In each semester of Printmaking 1, Mr. R. gave three introductory lectures, which lasted from 50 to 85 minutes, approximately six procedural lectures, which lasted about 30 minutes, approximately 4 procedural mini-lectures, which lasted 10 to 15 minutes, and approximately 20 procedural micro-lectures, which lasted from 30 seconds to 5 minutes. This is about 1/10th of the total class time. When he was not addressing the whole class, Mr. R. spent the majority of the rest of class time talking to students one-on-one and students were free to talk among themselves. I cannot gage accurately from my data how much student-student talk was art talk (and this amount would vary greatly from student to student). Based on my observations and recordings, I estimate that 20% of student-student talk was about art. The Sapir/Whorf hypothesis claims that the words we use affect thought and perception. Due to the great amount of talk in art classrooms like Mr. R.s, it is likely that teaching and learning in art are significantly shaped by the content of CAT.

http://ir.uiowa.edu/mzwp/vol2000/iss1/1

Cotner Classroom Marilyn Zurmuehlen Working Papers in Art Education, Vol. 2000 [2000], Iss. 1, Art. 1 Art Talk

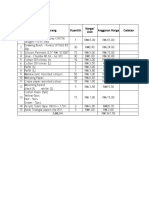

Finding 3. The four domains of art education, Art Criticism, Art History, Aesthetics, and Studio Practices (CHAS), do not get equal attention in CAT. As shown in Appendices A and B, Mr. R. and his students Talk Studio Practice most. Art Criticism is second. Art History is referred to much less than Art Criticism. And Aesthetics is barley touched upon at all. This trend is also noted in the episodes of student-student talk presented in Chapter 5. Of course, Printmaking 1 is a studio art class and it is no surprise that Studio Practice receives the most attention in the talk. However, it is notable that Art Criticism receives nearly as much attention as Studio Practices. Talking Art Criticism appears to be a natural companion to Talking Studio Practices. It is also notable that Art History and Aesthetics receive so little attention due to the fact that these are important domains of art education that are recommended components of art education in national, state, and local curricular mandates. In light of these mandates, CAT was inattentive to these two important domains in the classroom I studied. Finding 4. CAT includes direct, indirect, tangential, and ancillary references to the four domains of art education. These four types of references to art in talk can be considered on a continuum of strong to weak framing. For example, Historically, Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein may be the most famous Pop artists who did silkscreens is a strongly framed, or direct, art historical reference in comparison to Take a look at this old silk screen, which is on the other end of the continuum, a weakly framed, or ancillary art historical reference. What is most strongly framed (see Bernstein, 1971 in Eisner, 1991, p.76) indicates what is likely to be important to the speaker to communicate. This continuum of directness of references to the domains of art broadens what teachers can consider Art Criticism, Art History, Aesthetics, and Studio Practices (CHAS) in talk and highlights how framing in talk is likely to shape teaching and learning. Finding 5. CAT is primarily teacher-talk and thereby imbued with the curricular and social concerns of the teacher. As shown in Appendices A and B, teacher art talk far out weighs the amount of student art talk, ranging from about 3 times as much to 8 times as much. As mentioned above, studentstudent talk in class is only about 20% art talk. Considering that CAT carries both social and curricular messages, the great majority of art talk to which students are exposed in class is teacher-talk that is designed as communicationdeliberately and nondeliberately (Cazden, 1988)not only about art, but about the social dynamic between a teacher and his class. Students simply do not talk as much about art as they could. Lemke (1990) suggests that students must practice using the language of the disciplines they study in order to be understood by other practitioners of that discipline and to better understand the talk of other practitioners of that discipline. His point is about membership and communication within communities of speakers. My analysis extends Lemkes findings by adding that students must practice actually generating their own art talk because due to the social function of talk, simply mimicking the teachers talk may not sound, nor be, appropriate when spoken by a student. Also, based on Cazdens (1988) view of talk as propositional and social, students need to practice talking about art not only as a means of communication about art within the community of their art classroom,

http://ir.uiowa.edu/mzwp/vol2000/iss1/1

Cotner Classroom Art Talk Cotner: Classroom Art Talk: How Discourse Shapes Teaching and Learning in

but also as a necessary means of maintaining their social role in the classroom when engaged in discourse about art. Finding 6. CAT focuses on characteristics of art that simultaneously support social functions critical to speakers roles in the classroom. This study has shown examples in each context of CAT of how CAT is simultaneously curricular and social. Because teacher and students must continuously maintain their social roles in the classroom, those aspects of art that can also facilitate maintenance of social dynamics are stressed to most in talk. For example, in teacher CAT, making comparisons between (1) how novices and experts do artwork, (2) saying that art is hard work, and (3) telling students that they have autonomy (choice) concerning certain aspects of their work explicitly explains processes of art and implicitly prescribes how students will behave in class, i.e., they will (1) work like novices, (2) work hard, and (3) make their own choices. (Making their own choices appears to enhance motivation in light of the dubious tasks of working like novices and working hard.) In interviews with students, these three charcateristics of art were mentioned repeatedly as what students felt they were learning about art. Thus, such topics have both curricular and social outcomes that are conducive to the high school art classroom. Similarly, in student-student art talk, compliments, for example, attend to successful qualities of student artwork and maintain or build good feelings between peers. The teacher CAT mentioned above attends to general characteristics of art, but is inattentive to particulars, such as, what are the different qualities we can perceive in novice versus expert artwork, in what ways is art hard work, and what kinds of choices do artists make in their autonomous roles as creators of art. In student art talk, compliments attend to successful qualities of student artwork, and maintain or build good feelings between peers, but are inattentive to less successful qualities, that could enhance the artwork and extend the learning experience for both speakers. Recommendations for Teachers 1. Encourage students to participate more in CAT because they need to develop ways of talking about art that are compatible with their role as student in the classroom, rather than just mimicking the teachers talk. 2. Encourage students to use art-specific vocabulary (with each other and with the teacher) because although they can communicate with more common terminology, the richer art terminology can enhance the quality of their talk and consequently may enhance the quality of their learning. 3. Strongly frame (be direct) all four domains of art education in talk at different times so that students can distinguish between them and recognize each as important. 4. Recognize that even ancillary references to art in talk can shape teaching and learning. Less direct references can be used to generate lists of starting points for more direct, or strongly framed, discourse in the different disciplines. 5. Require students to read and write about art so as to extend their exposure to discourse about art beyond the plentiful, but limited scope of CAT.

http://ir.uiowa.edu/mzwp/vol2000/iss1/1

Cotner Classroom Marilyn Zurmuehlen Working Papers in Art Education, Vol. 2000 [2000], Iss. 1, Art. 1 Art Talk

Recommendations for Further Research Further studies could focus on: 1. The effects of age, gender, and socioeconomic status on CAT. 2. The effects of structured small group work on CAT. 3. The effects of strongly framed in comparison to weakly framed CAT on learning. 4. The effects of CAT on qualities of artmaking. 5. The effects on student-student art talk on learning.

http://ir.uiowa.edu/mzwp/vol2000/iss1/1

Cotner Classroom Art Talk Cotner: Classroom Art Talk: How Discourse Shapes Teaching and Learning in

References (from Abstract only)

Cazden, C.B. (1988) Classroom Discourse: The language of teaching and learning. Portsmouth:

Heinenmann.

Eisner. E. (1991). The enlightened eye: Qualitative inquiry and the enhancement of educational practice. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc. Eisner, E. (1988). The role of discipline-based art education in Americas schools. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Trust. Efland, A (1976). The school art style: A functional analysis. Studies In Art Education, 17 (2), 37-44. Lemke, J. L. (1990). Talking Science: Language, Learning, and Values. (Judith Green, Series Editor) Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation. National Standards for Arts Education: What Every Young American Should Know and Be Able to Do in the Arts (1994) Reston, VA Music Educators National Conference. Visual and Performing Arts Framework for California Public Schools: Kindergarten Through Grade Twelve (1996) Sacramento, California Department of Education. Wilson, B. (1997). The Quiet Evolution, Los Angeles: The Getty Education Institute for the Arts. Whorf, B. L. (1956) Language, Thought, and Reality. (John B. Carroll, ed.) Cambridge: The MIT Press.

http://ir.uiowa.edu/mzwp/vol2000/iss1/1

Cotner Classroom Marilyn Zurmuehlen Working Papers in Art Education, Vol. 2000 [2000], Iss. 1, Art. 1 Art Talk

CAT CODING SYSTEM

CURRICULAR LEVEL talking art criticism t/sC talking art history t/sH talking aesthetics t/sA talking studio practice t/sS SOCIAL LEVEL teacher credibility t/sTC student credibility t/sSC teacher power t/sTP student power t/sSP IMPLICATURE & INFERENCE dialogic flow t/sDF patterns and vocabulary t/sPV non-linguistic acts t/sNL

Cotner 2000 Figure 3 (From Chapter 1, page 24.)

Examples Context2

32. Mr. R.:

CURRICULAR LEVEL

Cause that would give us something.=

SOCIAL LEVEL IMPLICATURE & INFERENCE

tS

Refers to result of studio practice.

tSP

Teacher limits student power by extending his speech despite the fact that the student begins to say something, signified by, um.

tDF

Teacher cuts-off speech of student, interrupting synchrony of their discourse.

tC

Assesses projected result of suggested change.

tA

Attributes a human quality to artwork, namely, giving.

tTP

Teacher grants himself the power in this moment of discourse to finish his thought and establishes himself as member of decision-making team with student artist.

33. Norman (student): =I

CURRICULAR LEVEL

was doing this on purpose,

SOCIAL LEVEL IMPLICATURE & INFERENCE

sS

Student refers to the studio practice he employed this is, in effect, a reference.

sSP

The student now claims power in the conversation by interrupting the teacher.

sDF

Student repeats interruption of synchrony of text demonstrates use of standard.

sH

In effect, this is a reference to the history of the artwork.

sTP

The power the teacher exhibited in the previous line is countered by the students claim to power.

PV

Student uses standard vocabulary concerning artmaking, purposefulness. This is an example of use of standard terminology in order to contradict the teachers implied suggestion that the student was intimidated by a certain aspect of this process.

sSC

Student claims credibility via the purposefulness of his actions while making this piece of art.

http://ir.uiowa.edu/mzwp/vol2000/iss1/1

10

You might also like

- MAI8 - 1962-1974 Minimalism and ConceptualismDocument47 pagesMAI8 - 1962-1974 Minimalism and ConceptualismTrill_MoNo ratings yet

- IB Unit Express YourselfDocument7 pagesIB Unit Express YourselfKathyNo ratings yet

- Compliance Management CertificateDocument4 pagesCompliance Management CertificatetamanimoNo ratings yet

- Names: Jocelyne Ramirez Subject Area(s) : Music Lesson Topic: Grade Level(s) : 11-12Document4 pagesNames: Jocelyne Ramirez Subject Area(s) : Music Lesson Topic: Grade Level(s) : 11-12api-519832820No ratings yet

- 9542b-Minimalism Syllabus 2015Document6 pages9542b-Minimalism Syllabus 2015scottvoyles6082No ratings yet

- Transcendentalism UnitDocument14 pagesTranscendentalism Unitapi-402466117No ratings yet

- Dele Exam 2019Document3 pagesDele Exam 2019johnjabarajNo ratings yet

- Evidence 2 6Document8 pagesEvidence 2 6api-325658317No ratings yet

- My Unit Plan - Brodie West 2095567Document9 pagesMy Unit Plan - Brodie West 2095567api-267195310100% (1)

- Brief history of the educational math game DamathDocument3 pagesBrief history of the educational math game DamathLeigh Yah100% (1)

- M. Parsons Art and Integrated Curriculum-1Document22 pagesM. Parsons Art and Integrated Curriculum-1Tache RalucaNo ratings yet

- Teaching in Specialist Areas: Key Aims and Philosophical IssuesDocument12 pagesTeaching in Specialist Areas: Key Aims and Philosophical IssuesKan Son100% (2)

- DIS Okd Action Plan 2022 2023Document3 pagesDIS Okd Action Plan 2022 2023Winie -Ann Guiawan100% (1)

- DRR Teaching Guide WordDocument61 pagesDRR Teaching Guide WordCharline A. Radislao100% (3)

- Still Life Lesson PlanDocument8 pagesStill Life Lesson Planapi-528337063No ratings yet

- Assignments across the Curriculum: A National Study of College WritingFrom EverandAssignments across the Curriculum: A National Study of College WritingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Artistic and Creative Literacy G-3Document62 pagesArtistic and Creative Literacy G-3민수학100% (3)

- ABM - AOM11 Ie G 13Document7 pagesABM - AOM11 Ie G 13Jarven Saguin100% (1)

- Stylistic and Discourse Analysis Preliminary ModuleDocument15 pagesStylistic and Discourse Analysis Preliminary ModuleNicole Rose BinondoNo ratings yet

- Guidelines in Narrowing Down A Research TopicDocument2 pagesGuidelines in Narrowing Down A Research TopicKim Roi CiprianoNo ratings yet

- Name of The Project: Colors in Nature Project ObjectivesDocument6 pagesName of The Project: Colors in Nature Project Objectivessreetamabarik100% (3)

- The Case For Poetry Part IIDocument7 pagesThe Case For Poetry Part IIapi-262786958No ratings yet

- Blue Creek - Oxacan Wood Carvings - 5th GradeDocument21 pagesBlue Creek - Oxacan Wood Carvings - 5th Gradeapi-211775950No ratings yet

- UAP Global Issues Novel Study UnitDocument5 pagesUAP Global Issues Novel Study Unitapi-239090309No ratings yet

- Smagorinsky Personal NarrativesDocument37 pagesSmagorinsky Personal NarrativesBlanca Edith Lopez CabreraNo ratings yet

- Art History Syllabus For AntiochDocument5 pagesArt History Syllabus For Antiochapi-261190546No ratings yet

- Cultures in Crisis Course Explores Literary Works and Global IssuesDocument10 pagesCultures in Crisis Course Explores Literary Works and Global IssuesElizabeth CopeNo ratings yet

- Integrating The Arts To Facilitate Second Language Learning: Olga N. de Jesus, Ed.DDocument4 pagesIntegrating The Arts To Facilitate Second Language Learning: Olga N. de Jesus, Ed.DHamizon Che HarunNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan & Analysis: Urban Poetry in The Secondary Classroom Chris Mastoropoulos Mcgill UniversityDocument7 pagesLesson Plan & Analysis: Urban Poetry in The Secondary Classroom Chris Mastoropoulos Mcgill Universityapi-384656376No ratings yet

- "So What." "Who Cares?" "Whatever.": Changing Adolescents' Attitudes in The Art ClassroomDocument14 pages"So What." "Who Cares?" "Whatever.": Changing Adolescents' Attitudes in The Art ClassroomEkica PekicaNo ratings yet

- HUMN01GDocument6 pagesHUMN01GJebbie Enero BarriosNo ratings yet

- KLA - Creative Arts Topic - Aboriginal Dot Painting Early Stage 1 Stage 3Document10 pagesKLA - Creative Arts Topic - Aboriginal Dot Painting Early Stage 1 Stage 3api-270277678No ratings yet

- Module 1 Reading in The Content AreasDocument6 pagesModule 1 Reading in The Content AreasChery-Ann GorospeNo ratings yet

- 2015 CV WeeblyDocument8 pages2015 CV Weeblyapi-260961368No ratings yet

- K To 12 Basic Curriculum Education Senior High School Core Subject 20231128 005258 0000Document37 pagesK To 12 Basic Curriculum Education Senior High School Core Subject 20231128 005258 0000ricotribiana12No ratings yet

- Real World Unit PlanDocument31 pagesReal World Unit Planapi-345950714No ratings yet

- Year 9 Baroque To Bartok Unit PlanDocument4 pagesYear 9 Baroque To Bartok Unit PlanMary LinNo ratings yet

- The Ethnography Seminar, 2018-19 PDFDocument11 pagesThe Ethnography Seminar, 2018-19 PDFAndyNo ratings yet

- Art and SocietyDocument10 pagesArt and SocietyChandan BoseNo ratings yet

- Teaching LiteratureDocument5 pagesTeaching LiteratureMarie Melissa IsaureNo ratings yet

- Art Lesson Plan - ReconsiliationDocument11 pagesArt Lesson Plan - Reconsiliationapi-285384719No ratings yet

- Icp Lesson Plan MusicartsDocument4 pagesIcp Lesson Plan Musicartsapi-303221914No ratings yet

- CBR - ART and ETHICS - Alda HannisahDocument6 pagesCBR - ART and ETHICS - Alda HannisahZerimah afgani HasibuanNo ratings yet

- Art 383: Medieval Art and Architecture in Europe: Sstone@Csub - EduDocument5 pagesArt 383: Medieval Art and Architecture in Europe: Sstone@Csub - Edust_jovNo ratings yet

- INST 1503-04 Syllabus Spring 2021Document6 pagesINST 1503-04 Syllabus Spring 2021Emma RoseNo ratings yet

- Literary Canon - Janne AustenDocument30 pagesLiterary Canon - Janne AustenAnonymous Wfl201YbYoNo ratings yet

- Good Copy 320 ProjectDocument9 pagesGood Copy 320 ProjectGorgus BorgusNo ratings yet

- Aesthetic Education of StudentDocument8 pagesAesthetic Education of StudentALEXANDRA-MARIA PALCUNo ratings yet

- Blue Creek - Harmony Hammond - 4th GradeDocument20 pagesBlue Creek - Harmony Hammond - 4th Gradeapi-211775950No ratings yet

- Esslinger MCF Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesEsslinger MCF Lesson Planapi-690327413No ratings yet

- Ap Art History Syllabus 2016-2017 - StudentsDocument10 pagesAp Art History Syllabus 2016-2017 - Studentsapi-260998944No ratings yet

- My Learning Journey in Ge6Document23 pagesMy Learning Journey in Ge6Bumatay, Angel Mae C.No ratings yet

- Intercultural Communication CourseDocument31 pagesIntercultural Communication CoursepitapitulNo ratings yet

- Critical Ethnography ThesisDocument8 pagesCritical Ethnography ThesisCheapPaperWritingServicesMobile100% (2)

- Improvisation Seminar Explores Diverse Musical TraditionsDocument5 pagesImprovisation Seminar Explores Diverse Musical TraditionsAnonymous xbVy8NTdVNo ratings yet

- Lectures 1 3Document119 pagesLectures 1 35q6r2pwbtwNo ratings yet

- Grade: 6 Subject: English Language Arts Multicultural Goal:: Introduction To PoetryDocument4 pagesGrade: 6 Subject: English Language Arts Multicultural Goal:: Introduction To Poetryapi-542540778No ratings yet

- Professional Growth PortfolioDocument18 pagesProfessional Growth PortfolioCarla MyskoNo ratings yet

- 320 ProjectDocument8 pages320 ProjectGorgus BorgusNo ratings yet

- Nterwoven: Culture, Language, and Learning Strategiesrebecca L. OxfordDocument24 pagesNterwoven: Culture, Language, and Learning Strategiesrebecca L. OxfordBrenda MoysénNo ratings yet

- L1Document54 pagesL1Евгения ХвостенкоNo ratings yet

- Art Craft CalligraphyDocument6 pagesArt Craft Calligraphyapi-23151687950% (2)

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument22 pagesInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelNo ratings yet

- Efland School Art StyleDocument9 pagesEfland School Art StyleinglesaprNo ratings yet

- Derrig Lesson One DraftDocument8 pagesDerrig Lesson One Draftapi-528337063No ratings yet

- Practicum PlanDocument34 pagesPracticum Planapi-401560883No ratings yet

- Deweyan Multicultural Democracy RortianDocument17 pagesDeweyan Multicultural Democracy Rortianucup.sama.us94No ratings yet

- 1Document2 pages1Yuni IsaNo ratings yet

- Sekolah: Alamat:: Penilaian:: Bil. Nama Murid Jantina No. My Kid / No. Kad PengenalanDocument5 pagesSekolah: Alamat:: Penilaian:: Bil. Nama Murid Jantina No. My Kid / No. Kad PengenalanYuni IsaNo ratings yet

- Auld Lang SyneDocument1 pageAuld Lang SyneYuni IsaNo ratings yet

- BI Y1 LP TS25 - PhonicsDocument22 pagesBI Y1 LP TS25 - PhonicsYuni IsaNo ratings yet

- Mastery Learning Language Applying WorksheetsDocument3 pagesMastery Learning Language Applying WorksheetsYuni IsaNo ratings yet

- Transit Form Writing Skills Y1 2018Document5 pagesTransit Form Writing Skills Y1 2018nithiNo ratings yet

- English WorkDocument1 pageEnglish WorkYuni IsaNo ratings yet

- A Happy Journey Ahead: Siti Nurannis Nazira (13.12)Document8 pagesA Happy Journey Ahead: Siti Nurannis Nazira (13.12)Yuni IsaNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 at SchoolDocument16 pagesUnit 1 at SchoolYuni IsaNo ratings yet

- Food List AinulDocument4 pagesFood List AinulYuni IsaNo ratings yet

- English Lesson: Numbers: Name: Tuesday/24 NOV 2020Document3 pagesEnglish Lesson: Numbers: Name: Tuesday/24 NOV 2020Yuni IsaNo ratings yet

- What Pupils Need To Do Examples of Possible Question StructuresDocument3 pagesWhat Pupils Need To Do Examples of Possible Question Structuresynna9085100% (1)

- Language PlusDocument6 pagesLanguage PlusYuni IsaNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson PlansDocument5 pagesDaily Lesson PlansYuni IsaNo ratings yet

- English Work 8 July 2020 - 11 July 2020: TH THDocument1 pageEnglish Work 8 July 2020 - 11 July 2020: TH THYuni IsaNo ratings yet

- Nota Minta PksDocument2 pagesNota Minta PksYuni IsaNo ratings yet

- GestaltDocument16 pagesGestaltYuni IsaNo ratings yet

- What Pupils Need To Do Examples of Possible Question StructuresDocument3 pagesWhat Pupils Need To Do Examples of Possible Question Structuresynna9085100% (1)

- Tambah MudahDocument8 pagesTambah MudahYuni IsaNo ratings yet

- LizardDocument8 pagesLizardYuni IsaNo ratings yet

- Classroom Objects StoryDocument5 pagesClassroom Objects StoryYuni IsaNo ratings yet

- Perbandingan Ggi (Ar1) Dengan Oti 1: A B C DDocument2 pagesPerbandingan Ggi (Ar1) Dengan Oti 1: A B C DYuni IsaNo ratings yet

- How To Write A Research ProposalDocument4 pagesHow To Write A Research ProposalMudit KhetanNo ratings yet

- Year 1 Score Sheet (Spell It Right)Document3 pagesYear 1 Score Sheet (Spell It Right)Yuni IsaNo ratings yet

- English Phonics LessonsDocument5 pagesEnglish Phonics LessonsYuni IsaNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Cefr Language ArtDocument1 pageLesson Plan Cefr Language ArtYuni IsaNo ratings yet

- RPH Week 1 2018Document7 pagesRPH Week 1 2018Yuni Isa100% (1)

- Box PlotsDocument2 pagesBox PlotsYuni IsaNo ratings yet

- Math DrillDocument1 pageMath DrillYuni IsaNo ratings yet

- CV of MMH PAd PDFDocument7 pagesCV of MMH PAd PDFAnonymous gOdPBM2No ratings yet

- Good MoralDocument8 pagesGood MoralGiovanne P LapayNo ratings yet

- Syllabus - SCH-MGMT 644 RDocument7 pagesSyllabus - SCH-MGMT 644 RKhamosh HoNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument5 pagesUntitledJeffrey Jerome Abejero BeñolaNo ratings yet

- UDL Lesson Plan TemplateDocument3 pagesUDL Lesson Plan TemplateEric Allen FraryNo ratings yet

- Sifat Resume UpdatedDocument1 pageSifat Resume UpdatedSakibul Alam KhanNo ratings yet

- Educ 6145 Project PlanDocument15 pagesEduc 6145 Project Planapi-278391156No ratings yet

- Ivy-GMAT RC Concepts PDFDocument39 pagesIvy-GMAT RC Concepts PDFMayank SinghNo ratings yet

- Web Results: What Is Answers May Vary? - Brainly - PHDocument6 pagesWeb Results: What Is Answers May Vary? - Brainly - PHStacy LimNo ratings yet

- Class Program Shs Second SemesterDocument3 pagesClass Program Shs Second Semesterrobelyn veranoNo ratings yet

- MSC Smart Electrical Networks (Smart Grid)Document2 pagesMSC Smart Electrical Networks (Smart Grid)Sadam ShaikhNo ratings yet

- FS1 Episode-13Document49 pagesFS1 Episode-13Aiza CatiponNo ratings yet

- General Scince ManualDocument13 pagesGeneral Scince ManualiyagiNo ratings yet

- ICE Training GuidanceDocument35 pagesICE Training GuidanceNagabhushana HNo ratings yet

- Importance of Parental Involvement in EducationDocument20 pagesImportance of Parental Involvement in Educationjoy pamor100% (1)

- Cia Rubric For Portfolio Project Submission 2017Document2 pagesCia Rubric For Portfolio Project Submission 2017FRANKLIN.FRANCIS 1640408No ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesArsee HermidillaNo ratings yet

- Challenges of Students in Learning The Islamic Yellow Book at Dayah Raudhatul Qur'an Darussalam, Aceh Besar, IndonesiaDocument14 pagesChallenges of Students in Learning The Islamic Yellow Book at Dayah Raudhatul Qur'an Darussalam, Aceh Besar, IndonesiaUlil AzmiNo ratings yet

- Mohammad Hanzalla Armand - FV - 2A - ReV (1) - Copy - Copy - Copy - Copy (No Email Moses)Document19 pagesMohammad Hanzalla Armand - FV - 2A - ReV (1) - Copy - Copy - Copy - Copy (No Email Moses)Mohammad Hanzalla ArmandNo ratings yet

- Classroom Management Case Study LessonDocument6 pagesClassroom Management Case Study Lessonapi-339285106No ratings yet

- A Study of Stress Factor and Its Impact On Students Academic Performance at Secondary School LevelDocument5 pagesA Study of Stress Factor and Its Impact On Students Academic Performance at Secondary School Levelbebs donseNo ratings yet

- Week 7 Worksheet: Unity in DiversityDocument3 pagesWeek 7 Worksheet: Unity in DiversityTrisha Mae QuilizaNo ratings yet