Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Towards Post-Consumerism:nature, Culture and The Politics of Consumption by Kate Soper

Uploaded by

5705robinOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Towards Post-Consumerism:nature, Culture and The Politics of Consumption by Kate Soper

Uploaded by

5705robinCopyright:

Available Formats

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.

07) Towards post-consumerism: Nature, Culture and the Politics of Consumption 1 Perennial Questions, Particular Anxieties First a few thoughts about contemporary ideas about nature their ecological reference The concept of nature has obviously been central to all discourse on the environment. It is nature, after all, that we are told is being damaged, polluted and eroded; and it is nature that we are enjoined to respect, protect and conserve. But

there is also much talk today about the end or disappearance of nature, where what is meant is that there is little or nothing of the environment that remains unaffected by human activity; and little studied in the biological and medical sciences that is not subject to human manipulation. Nature, we are being told, has now itself become the construct of human culture: an argument which sometimes carries the suggestion that, as we have constructed it, so we have brought about the destruction of its authentic or pristine form.1 In this it reflects our ecological anxieties about pollution and resource depletion. But it also registers our doubts about what still counts as natural in a world so technically controlled and made over by human beings. Such claims, by presenting humanity and its work as antithetical to those of nature, invite us to think that human culture is external to us, or set apart from, the natural order. Yet clearly we are also in some sense natural animals who have biological features and ecological dependencies akin to those of other living creatures. So we have to ask in what the separation consists and in pondering this, we are in turn led on to further questions about the lines of division between the cultural and the natural. What are the difference between what human beings are, do, and make and the being and doing of other creatures ? Why, for example, are animal constructions such as the ant heap or beehive seen to belong to the natural environment, whereas even the most primitive human of human dwellings are looked upon as an artificial excrescence ? What is it exactly that makes us think that some parts of the

Though this is also presented in some discourse as something to be theoretically registered rather than deplored. In a recent influential text, for example, we read that there is no singular nature as such, only natures, and that these are historically, geographically and socially constituted. (MacNaghten and Urry, 1998: 15; cf. Giddens, 1994). This position is also represented in the arguments of those theorists who, under the influence of Michel Foucault, have insisted that there is no natural body or sexuality, and that even needs, instinct and basic pleasures must be viewed as the worked up effects of discourse and that everything which is presented as natural must be theorized as an imposed and inherently always revisable norm of culture. (cf. Butler, 1990; 1993; Bordo, 1988; Bailey, 1993). I return to some of these issues later.

1

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07) environment are more natural than others ? Is the city of Budapest, for example, less a part of the natural order than a Nature Park, or the latter less so than field system in

the countryside - and if so, why ? What is the difference between the beauty or value of a work of art and that of a beautiful aspect of nature (a landscape, a flower, a bird ?) Why do we tend to think of the real tree or flower as both more natural and thus as more beautiful than the artificial, even though the real plant may be just as much the product of human design (through breeding or training) as the fabricated flower ? In short, what boundaries do we want to observe and why between the organic and inorganic, between the human and the animal, between art, artifice and nature and how do the answers we give to these questions bear on our current ecological concerns about what we are doing to nature, and it to us ? [Here are some artworks that are themselves playing around with how their art differs from nature: [PIX.] And here are some insects and birds who seem to be imitating art: the male of the dance fly species wraps up little gifts of seeds or edible materials to attract the female, or if nothing edible is available, simply fakes a gift, leaving the wrapping without anything inside. The bower birds provide elaborately decorated arbours or love nests to attract their mates..[PIX]] II Culture and Nature 2000 It is true, of course, that alongside the use of nature as a term to discriminate between us and are doings and those of other animals, there is also its use to refer to the plenitude or totality in which humanity is included along with all other beings. This was an idea reflected in early Christian teaching on the Great Chain of Being and finds some green parallels today in the so-called Gaia conception of an holistic ecosystem, and in the emphases on the importance of preserving bio-diversity (PIX). Yet even if we allow that all living beings exist in the largest sense in some kind of integral whole, we must still recognise that without humanity there would be no concept of nature in the first place, no distinction between the natural and the cultural, and none of the differences we have noted between nature and artifice or art. Human beings, moreover, are able consciously to monitor and, at least in principle, adjust their impact on the environment in ways denied to other creatures. So even though we see ourselves as broadly part of the natural order, there are also grounds to emphasise our distinction within and even, in key respects, our separation from it.

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07) Indeed, environmentalists often present themselves as seeking to preserve nature from human intrusion and contamination. The eco-warriors protesting against road and airport expansion, for example, see themselves, or at any rate are depicted by the media, as locked in a battle for the protection of nature against the further encroachments of the human. (PIX) From this perspective, nature has intrinsic value: it is an independent good worth cherishing in itself, and not simply as a source of raw materials available for human use. It is the perspective of those one might call the nature endorsers. The nature endorsers want us to abandon

anthropocentric conceptions of humanitys privileged place within the eco-system and to overcome what they see as our alienation from nature by recognising our kinship and continuity with other living creatures. They thus summon us to a form of metaphysical re-enchantment of the natural world (although one that is often said to reconnect with some past tradition of environmental care or stewardship). With the exception of some eco-feminist forms of argument and New Age spiritualism, one is speaking here of what is essentially a symbolic re-enchantment: a call to appreciate the true worth, vital qualities or (inverted commas) meaningfulness of the natural world rather than a profound challenge to its scientific understanding. But it represents a powerful critique of Enlightenment humanism and scientific positivism and is widely influential within green politics. (Ross 1994a: 222236; Soper 1996). Yet compelling as this position is in many ways, the demand to respect nature in this way does tend to imply that there is a clear cut idea of what counts as a natural environment, and this can be a problem. If, for example, we think of nature as that which is wholly independent of, and unaffected by, humanity, then very little of what we loosely think of as the natural environment woodlands, wetlands and their flora and fauna, the English Downs or the Magyar Plain can qualify for the term. Even the parts thought to be wildest are for the most part a culturally modified landscape bearing the imprint of centuries of human habitation and management. Marx wryly pointed out over a century ago that the nature which preceded human history no longer exists anywhere (except perhaps on a few Australian coral-islands of recent origin.) (Marx, [1845] 1968: 59). We should also note that our preference for wild nature is itself a cultural effect. Tastes in landscape have changed considerably and themselves reflect responses to industrial activity. The mountainous regions and rugged landscapes that began to come into fashion for their sublimity in the C18th and remain much 3

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07) admired today were in an earlier period regarded as distressing legacies of the Flood or thought of as ugly and inhospitable. Nature, in fact, only began to figure as a

positive power and to be valued in its sublime and untamed aspects at the point where human mastery over its forces became extensive enough for aesthetic exaltation in wilderness to replace blind animal terror. (PIX) The romantic view of sublime nature is in this sense a manifestation of the same human powers over nature whose destructive effects it laments (Boulton, 1958: xliv-lxxii; Burke 1756, Kant, 1790; Monk, 1935; Nicolson, 1958; Tuveson, 1960, Chap 3). What counts as being beautiful or having intrinsic value in nature is thus conditioned by economic and social factors that are in turn mediated through their representation in art, literature, and other forms of imagery. And in our own time, the value now placed on species protection and wilderness preservation is itself caught up in the processes of globalization and generating social iniquities of its own. (Cf.Wilson,1992). Eco-tourism, for example, which is now the fastest growing sector of the worlds largest industry is providing new nature-sensitive playgrounds for the more affluent but at the cost quite often of dispossession and violence against indigenous peoples as has taken place in Bangladesh, Brazil, Masai, Botswana and elsewhere. Much of this eco-tourist incursion comes as part of a development package funded by international banks and is defended as part of an integrated programme of poverty alleviation and environmental conservation. The reality, however, according to the campaigning charities involved, is that this is a nature-endorsing exercise that is often no less exploitative and destructive of local communities than other globalized industries. And the impact, of course, of flying to ones favoured wilderness is itself caught up in their destruction. The airflights that take eco-tourists see the threatened polar-bears are themselves destroying their habitat. (PIX) In general, then, we should recognize that what we define and value as the difference or otherness of nature is itself culturally formed, both in a physical sense and in the sense that perceptions of its attractions are culturally shaped. To complicate matters further technological developments in recent times have blurred the line between the natural and the cultural. Some have argued that the computer with its mechanical extensions of mind and memory and its creation of virtual realities, is making redundant any distinction between the organic and the inorganic, and that we should think of ourselves increasingly as cyborg entities, part 4

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07) machine-like, part organic. Innovations in medicine and genetic engineering have been cited to similar effect. Organ replacements, gene therapy, cloning, genetically modified seeds and foods, the creation of transgenic entities such as Dolly the Sheep or OncoMouse (PIX): all this, it is said, serves to render ever more fuzzy the divisions between the human, the animal and the machine. These advances also indicate the extent to which what is natural in the sense of being alive and organic has itself been transformed by, even become the construct of, human technologies.

In the argument of some theorists, moreover, - those one might term nature sceptics2 but who also called themselves post-humanists this fuzziness or conceptual instability is regarded as a kind of emancipatory advance that allows us to realize and celebrate forms of being and sexual expression that were previously denounced as perverse or counter-nature (Haraway 1991 Ch. 8, 1997; Gray 1995; Peperell 1995; poster, 1996; Plant, 1996, Broadhurst Dixon and Cassidy, 1998).3 Amidst this plethora of accounts of nature and of the human role both in its destruction and in its construction, it can be difficult to find ones bearings. One thing, however, does seem clear: that it is only because we do (and arguably cannot but) observe distinctions between the human, the animal, the biotic and the inorganic, that we experience the ethical concerns we do about the future of nature. If we were literally no longer to notice these differences then neither Dolly the Sheep, nor OncoMouse, nor the prospect of human cloning, nor artificial brain implants, nor any of the current sources of alarm about Frankenstein science would cause us any grief. So those who recommend we overcome our humanist commitments to those

2

Where, then, the nature-endorser refers us to an independently real and pre-discursive nature that is being lost, wasted and polluted, the nature-sceptic directs us to the ways in which relations to the nonhuman world are always historically mediated, and indeed constructed, through specific conceptions of human identity and difference; and where the one calls on us to respect nature and the limits it imposes on cultural activity, the other draws attention to the erosion of the distinction between the organic and the artefactual, targets the cultural policing functions of the appeal to nature and invites us to view the nature-culture opposition as itself a politically instituted and mutable construct.

Instead of seeking salvation through a return to nature, this type of position claims that progress can only come about via the estrangements of a post-humanist transcendence of the natureculture polarity. In their recent and influential work on the condition of global empire Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri tell us, for example, that human nature is in no way separate from nature as a whole, that there are no fixed and necessary boundaries between the human and the animal, the human and the machine, the male and the female, and so forth () nature itself is an artificial terrain open to ever new mutations, mixtures and hybridizations (Hardt and Negri, 2000: 215216; cf. Soper, 1999; 2003). And they present political resistance to the oppressions of capitalist globalisation as dependent on the emergence of new and alien forms of subjectivity centred on gender and sexual transgression, mutant modes and cyborgism.

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07) outdated divides may be undermining the bases of fundamental moral concerns whether for human rights or for the preservation of nature. What also seems clear is that none of the arguments about the end or the construction of nature can dispense with a distinction between the nature which human beings do not and cannot create and the nature which is the consequence of

their interventions. Even the most sophisticated experiments in genetic modification work with, and are dependent for their success upon, pre-given biological laws and processes. In this sense there is always a nature that is not the construct of human culture and technology but is the primary condition and context of any cultural intervention and manipulation in the first place. This applies equally to the largerscale forms of human interaction with the environment, where there is always a distinction to be drawn between the powers and processes which are the essential precondition of all agricultural practice, on the one hand, and the humanly modified landscape and its plant and animal life, on the other. To spell it out briefly, there is always a distinction between (A) the use of the term nature to refer to the structures, processes and causal powers that are constantly operative within the physical world. (It is these that provide the objects of study of the natural sciences, and condition all the possible forms of human intervention in biology or interaction with the environment. This is the nature to whose laws we are always subject, even as we harness them to human purposes, and whose processes we can neither escape nor destroy); and (B) the use of the term nature (as it is employed in much everyday, literary and theoretical discourse), to refer to ordinarily observable features if the world: the natural as opposed to the urban or industrial environment (landscape; wilderness; countryside; animals, domestic and wild, the physical body in space and raw materials.) This is the nature of immediate experience, representation and aesthetic appreciation; the nature we are said to have destroyed and polluted and are asked to conserve or preserve. For the most part (and one is presuming here that even wilderness bears some traces, however minimal, of their human modification) it is nature in this second sense which is the more directly experienced, and the object of our emotional and aesthetic responses. It is this nature, whether in the form of panoramic landscape or the detail of flora and fauna, which we love as a source of beauty and solace, and whose loss 6

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07) or destruction is lamented. It is also, of course, nature under this aspect for which human beings must assume responsibility and exercise ecological choice.

III Nature, Politics, Consumption From the perspective of this distinction, one has to criticize the posthumanists or nature-sceptics for being too ready to deny or disregard the difference between nature conceived as permanent causal powers and its surface effects too ready, that is, to deny or abstract from the nature that is in play in all our human activities and responses, and whose laws we have to understand and observe in all our scientific applications, medical transformations, and projects in genetic engineering whether of the physical environment or of our own and other life-forms. In this sense they are wrong to claim that nature is entirely invented or constructed by us. On the other hand, - if we turn now more directly to the implications for green politics - I think we also have to take issue with the argument of those environmental philosophers who invite us to believe that ecological harmony can be restored provide we respect to the so-called intrinsic values and needs of nature and revert to a supposedly more natural way of living. It is precisely because a regard for the immediate interests of nature (where this is conceived in terms of protection of nonhuman species, wilderness, etc.) may be consistent with the least democratic political methods, and the implementation of totalitarian methods of controlling human consumption, population and migration that anyone with concerns for global equity, gender parity and the collective well-being of future generations must reject a simplistic theory of natural value. (cf. Soper 1995: 160179, 1997). The attempt to accommodate ecological scarcities can be made in a variety of ways (capitalist, socialist, authoritarian, fascistic) all of them disputing what it means for human beings to flourish and whether some groups should be allowed to do so more than others. In fact, what is important about the emergence of the green movement is not that it supplies us with a definite political agenda but that, as Bruno Latour (1998), has put it, it suspends our certainties with regard to the sovereign good of human and non-human beings, of ends and means. It makes us think again about what living in harmony with nature or in an ecologically viable global order might entail, about how it bears on current conceptions of the good life, about what we are ready or not so ready to do as a means to its acheivement.

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07) In line with this, I would argue that the current ecological situation is to be illuminated primarily not by reference to the intrinsic qualities of non-human nature nor by recalling human beings to their fundamental kinship with other living creatures, but by consideration of the fraught nature of their own distinctively human condition as beings who are like other animals in their reliance on environmental resources for the supply of all their material needs, but unlike them in the urge they have to engage in a more than reproductive existence- to fulfil themselves through dynamic and innovative forms of cultural transcendence and individualising self-expression. Considered very abstractly, we may view the ecological crisis faced by humanity as a crisis concerning these contrary dimensions of human existence and their respective needs and modes of satisfaction. Capitalism, industrialisation, Western civilisation: all this can be viewed in the broadest sense as generated in

response to the urge to transcendent forms of fulfilment and the escape from a more animal and cyclical mode of existence. Yet many of the sources of satisfaction offered through this dynamic of capitalist globalisation are reliant on social exploitation and are ecologically unsustainable. This indicates a need to re-think the nature and conditions of human flourishing in such a way as to shift the dynamic of human pleasures and modes of self-fulfilment away from its current consumerist model of satisfaction and allow gratification through other, less polluting and resource intensive modes of consumption. The need here, in other words, is to find ways of reconciling the ecological and egalitarian need for a more cyclical and sustainable use of resources with the more distinctively human and individualist need for continuous cultural innovation, enhanced gratification and self-expression. Can we find ways of living rich, complex, creative, non-repetitive lives without social injustice and without too much environmental damage? The problem here is not how how to go beyond humanism (if by that is meant blurring or collapsing what is distinctive to our capacities and moral sensibilities); but nor is it how better to respect or get back to nature (in the sense of reverting to tradition, simplicity and a more animal way of being), but how to advance to a form of future that is both assertively human and ecologically benign. The focus, in short, should fall less on the adoption of the right attitudes or ways of valuing nature, and more on the essential conditions of human fulfilment and whether and how the good life can be collectively secured in an ecologically sustainable mode. 8

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07) When looked at from this perspective, global environmental problems are recast as problems of human consumption, and in a two-fold and interconnected way. First, there is the problem of the huge disparity between rich and poor in their access to resources, and hence to the minimum of material conditions essential to any further flourishing. Redressing this imbalance, I would argue, is both a moral and pragmatic imperative: a demand not only of social justice, but a prerequisite of any long-term, global, ecological well-being. It is true that a concern for pollution and resource attrition does not in itself imply a commitment to furthering global equality and justice, and that in the shorter term even quite severe ecological damage and depletion can be accommodated within the present, very unfair structure of distribution. But the longer we continue along that path, the more acute the competition for resources is likely to become, and the more uncivil the methods to which the societies of relative affluence could have recourse to in defending their advantage.

These methods might well over time come to include measures that most members of those societies would currently regard as deeply repugnant (the quite blatant and cynical manipulation of poverty, disease and famine to control global population; the coercion of Third World economies into an almost exclusive servicing of First World needs for bio-fuels and other energy substitutes; ever more fascistic policies on immigration to check the flow of eco-refugees from the more devastated areas of the globe). These are measures which are likely to encourage increasingly desperate forms of terrorist activity and could very well end in genocidal and even terminal forms of global warfare. In this sense, a more equitable distribution of both resources and the burden of pollution will be essential to any more permanently secured accommodation of existing and future ecological constraints. IV Consumerism and its Discontents The other major problem, as indicated, and to which I now want to come on, is that of consumerism, the problem that human flourishing is currently so widely perceived both by those in a position to enjoy it (for the most part affluent Westerners), and by those who lack the means to do so, as dependent on an everenhanced consumption of material goods and luxury services. The two problems connect in the sense that pressures for a more egalitarian distribution of resources between rich and poor are unlikely to be applied unless and until the good life is 9

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07) reconceived along less consumerist lines. Any such re-conception will involve a rethinking of the nature of pleasure and personal fulfilment (an alternative hedonism); and a deeper and more informed concern with the impact of ones own consumption on that of others elsewhere. It will also mean breaking with the assumption that democratisation and enlightened policies on race, gender, freedom and human rights can only be carried on the back of conventional economic growth and its shoppingmall culture. If this were to happen, then an alternative and ecologically sustainable conception of the good life might eventually not only win

10

the support of consumers within the richer nations, but also come to figure as an ideal through which the less developed global communities can reconsider the conventions and goals of development itself and thereby arrive at a better understanding of the more negative aspects of NorthWest over-development and how to circumvent them. It goes without saying, however, that at the present time the responsibility for any shifts of thinking must fall primarily on the more affluent global communities. We need in this situation to challenge the presumption that the consumerist model of the good life is the one we want to hold on to as far as we can and that any curb on that will necessarily prove unwelcome and distressing. This has been the presumption of two of the more commonly encountered responses to global warming: there are the fatalists who are resigned to the prospect of ecological devastation. These see little point in Westerners mending their profligate ways since the impact globally will be so minimal. Every percentage reduction of carbon emissions in the UK, they point out, will be more than cancelled out by their increase in China or India. And then there are the technical fix optimists. These believe or hope - that new technologies will solve the problem, thus ensuring continued economic growth with very little alteration in our life-style. Provided we make the investment now, the pain, as these optimists put it, can be kept to a minimum. We might as well go on as we are say the fatalists. Do everything economically and technically possible to keep the damage to a minimum, say the optimists. But neither dwell on the negative consequences of Euro-American style affluence for consumers themselves (the stress, ill-health, congestion, pollution, noise, excessive waste); and neither suggest it might be more fun to escape the confines of the growth-driven, shopping-mall culture than to continue to keep it on track. We hear all too little, in short, of what might be gained by moving away from our current

10

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07) obsession with consumerist gratifications and pursuing a less work driven and acquisitive way of life.

11

In a sense, of course, it is hardly surprising that we hear so little of that given how much at present goes into persuading us that happiness lies in buying more things. The advertising budget for promoting consumerist spending is an estimated 435 billion dollars per annum, and according to a recent Human Development Report, the growth in advertisement spending now outpaces the growth of the world economy by a third. Such astonishing expenditure is indicative of the need to repress all inclinations towards freer forms of enjoyment and to reinforce a demand otherwise at risk of becoming sated or inured through continuous reiteration of the consumerist message. Businesses are ever fearful of what they term need saturation, and bent on the development of new purchasing whims. According to a director of the General Motors Research Laboratory, the aim of business must be the organised creation of dissatisfaction; or as another senior executive, cited in Naomi Kleins No Logo, has put it with even greater candour, consumers are like roaches you spray them and spray them and they get immune after a while. Hence the need for ever more powerful stimuli to buy. Advertisers are also now targeting children at an ever younger age and employing increasingly bizarre and manipulative strategies in order to groom them for a life of consuming. The other pleasure to consumerist pleasure, is, then, currently so marginalized, occluded and denied its own advertisement and representation that any choice and decision in the matter has been more or less eradicated. Yet despite this virtual repression of alternatives, there are signs of a growing disaffection with the quality of life within affluent society itself. Shopping, it is true, is still the favourite way of spending time for many people, and there has been precious little reform in the use of the car and air flight, yet there is also disenchantment with the negative by-products of the affluent lifestyle, and a growing sense that it may stand in the way of other equally, if not more valued, goals. Several forms of convenience consumption - including car and air travel - have now been compromised by alarms about their safety, their ecological side-effects, their impact on health and their anti-hedonist repercussions for the good life itself. Such disaffection may find expression in nostalgia for certain kinds of material, or objects or practices that no longer figure in everyday life as they once did; it may lament the loss of certain kinds of landscape, or spaces (to play or talk or loiter or meditate or 11

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07) commune with nature); it may deplore the fact that were it not for the dominance of

12

the car, there would be an altogether different system of provision for other modes of transport, and both rural and city areas would look and feel and smell and sound entirely different. Or it may just take the form of a vague and rather general malaise that descends in the shopping mall or supermarket: a sense of a world too cluttered and encumbered by material objects and sunk in waste, of priorities skewed through the focus on ever more extensive provision and accumulation of things. Anxieties of this kind are, of course, by no means universal, and tend at present, for obvious reasons, to be largely confined in the UK to those in the middleand upper-income brackets. They will also very often be experienced in conflict with other, more immediately pressing concerns over employment security. Those who are dependent for their livelihood on the less eco-friendly forms of production and consumption will not find it so easy to be enthused about any ecologically prompted fall-off in demand for these commodities. Yet we can still point in recent times to higher and relatively diversified levels of consumer interest in ethical spending and investment, and public support for anti-pollution legislation, more organic methods of agriculture, and curbs on road and airport extension. We are witnessing, we might argue, the emergence of a new, more contradictory structure of consumer needs whereby some consumers are looking to less ecologically and socially exploitative lifestyles in order to escape the undesirable by-products of their own formerly less questioned sources of gratification. And we might note in this connection the recent evidence of economic studies suggesting that the increase in wealth and material possessions is no guarantee of an increase in happiness; and also the findings of the Happy Planet index recently compiled by the UK based New Economics Foundation. (PIX). Given all this, there is a place for being more assertively utopian in promoting sustainable consumption, both in the sense of being willing to offer blueprints or projections of other possible futures, and in the sense of promoting cultural works that encourage a different feeling and aesthetic response to the material culture of our times. Advocates of postconsumerism will not only reject the back to the Stone Age conception of its agenda as failing to recognise its innovative quality, but also highlight the more backward, puritan and ugly aspects of a work-driven and materially encumbered existence. Today, for example, despite the immense gains in the productivity of labour we are still subject to a time-economy that is proving ever 12

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07)

13

more environmentally damaging and is now seriously distraining on human and wellbeing. Those of a more optimistic cast who anticipated a future age of leisure have been confounded, and very few of the benefits we might have reaped in the form of free time from the unprecedented productivity of the last century have been realised. Dramatic illustration of the opportunities missed in this respect is provided in Juliet Schors book on The Overworked American (1991): Since 1948, productivity has failed to rise in only five years. The level of productivity of the US worker has more than doubled. In other words, we could now produce our 1948 standard of living (measured in terms of marketed goods and services) in less than half the time it took in that year. We actually could have chosen the four hour day. Or a working year of six months. Or, every worker in the United States could now be taking every other year off from work with pay. Incredible as it may sound, this is just the simple arithmetic of productivity growth in operation. (p.2) In fact, what happened in the US, where, as elsewhere, any political choice in the matter was ruled out by the dictates of the economy, was that free time fell by nearly 40 % since 1973 so although the average American by 1990 owned and consumed more than twice as much as he or she did in 1948, they also had considerably less leisure. Similar trends are signalled in the UK, where a steady decline in work hours since the mid-nineteenth century was halted in the 1990s, and where two-fifths of the workforce are now working harder than in the 1980s. It may be true that today those who put in most hours on the job are driven less by the need for more money than by their ambition or sheer addiction to the workaholic routine Yet the blurring of the work-life distinction that is the almost inevitable accompaniment of the 60-70 hour week and constant availability comes at enormous personal cost, and in an important sense erodes the possibility of any other form of fulfilment. There are now Wife Selecting and speed dating agencies pandering to the pathology of those whose job addiction has cost them all sense of the art of living. There is a whole service industry supplying round the clock childcare to those who can no longer spare the time for it themselves. There are increasingly bizarre work practices and divisions of labour (couples, for example, doing back to back shifts) in those cases where childcare is simply proving too expensive. A recent UK study covering 1,074 working and co-habiting adults over the age of 18, found

13

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07)

14

that more than a fifth of couples were so busy they could go for a week without seeing each other, often with serious impact on their relationship. Sceptics will always question whether there really is a need for more free time, or whether people are genuinely capable of benefiting from it. But in a culture where being in work is associated so closely with personal success, and those without work are almost always deprived of the funds, amenities and forms of education needed either for the carefree enjoyment of idleness or for the more concentrated and passionate pursuit of private hobbies or cultural or sporting activities, it is hardly surprising if free time is seen as a problem rather than a source of fulfilment. We cannot predict for certain how people would react to less work were it no longer so closely associated with the stigmata of idleness, unemployment and reduced citizenship. We should also not overlook the existing evidence that long hours and workaholic culture effect the capacity of people to relax and cope with leisure time. There is, in any other words, a reinforcing work ethic dialectic which needs to be reversed and replaced along alternative hedonist lines, so that by working less we also come to find it easier to relax. I suggest, then, that we need to challenge the presumption that progress and development are synonymous with speeding up, saving time and producing more. And we need to develop a counter-aesthetic to that of consumerist advertisement: an aesthetic revisioning whereby the commodities that are currently perceived as enticingly glamorous come gradually instead to be seen as cumbersome and ugly in virtue of their association with unsustainable resource use, noise, toxicity or their legacy of unrecyclable waste. The revisioning in question here is closely aligned with a general re-thinking of pleasure and the good life that would be achieved through a green renaissance. Comparably to the way in which there is a necessary regulation between ethical concern for an object and true beliefs about it (cf. ONeill:1994: 27) there is a regulation between beliefs about and aesthetics responses to material culture. If, for example, you come to know that x does you harm, you tend to perceive it differently. Advertisers have long been aware of this and revised their appeal in the light of these shifting regimes of truth and belief. No one could today market an antigreenfly spray, as was the case in the 1950s, with an image of mother, father and child all wreathing themselves in clouds of pesticide as they assault the rosebush (cf. Wilson, 1991: 99). (PIX) Cigarette advertisement had, until it was finally banned in the UK, to be emptied of any imagery of actual smoking. (PIX) Car advertisement 14

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07) has becomes increasingly reliant on an implausible depiction of the vehicle as a solitary in nature. The green renaissance would harness this interdependency of

15

belief and aesthetic experience for its own counter-consumerist purposes, and seek to extend it to the environment at large, such that goods that were unsustainable, even though not responsible for any immediate personal damage, ceased to exercise their one time aesthetic compulsion and were no longer perceived as seductive. Images of waste may have an important part to play in these aesthetic shifts, since the junk excreta of consumerist society is so plainly and repellently undesirable. Bonominis RSA Weee Man (a 300 ton, 24 foot high android constructed out of the average weight of the Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment, or Weee, that a single person disposes of in a lifetime) that loomed menacingly over the Thames in the spring of 2005, provided an instance of the kind of intervention that could contribute to the anti-consumerist aesthetic shift (Akbar, 2005: 3).(PIX) Lest it appear, however, as if all the emphasis in this account is falling on the greening of the individual consumer, it should be emphasised that collective strategies for changing consumption must also play a crucial role. The two pressures for change are intimately related, at least in democratic societies, where more collective and institutionally based measures for environmental protection and conservation are always ultimately reliant on the support of the electorate. If I have here stressed the emergence of greater individual consumer equivocation, it is precisely because of its potential political role in forcing governments into promoting more effective collective policies on the environment both at the national and international level. Collective and individual responses are not, in this sense, to be viewed as opposing or alternative forces for consumer change, but rather as interconnected and mutually reinforcing , since the greening of the individual consumers is a precondition of the kind of consensus and electoral mandate that would permit the imposition of forms of collective control over the environment and public self-policing of the more ecologically destructive types of consumption. Equally, and conversely, collective strategies which focus, for example, on the provision of public transport or the greening of urban space, are likely themselves to issue in benefits (healthier environments, reduction in congestion, greater safety) that encourage more extensive individual consumer support. In arguing for these moves towards post-consumerism, I am not underestimating the difficulties of building support for an alternative politics of 15

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07) consumption. But they can, I think, further the desire for changes in social and

16

environmental policy by pointing to the other possible structures of pleasure intimated in the dissatisfactions with the present. Visions of sustainable societies can help to catalyse the political will for change, and it is in this sense that utopian projection should be understood as a realist or pragmatic contribution to the securing of a fairer and more ecologically sensitive world order. For it seems quite implausible to suppose that we can, either socially or environmentally, continue with current rates of expansion of production, work and consumption over the coming millennium let alone into the more distant future.

16

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07)

17

Appendix: A Realist and Humanist Critique I here provide a little more theoretical backing for some of these arguments and indicate what I see as their main ethical and political implications. In What is Nature ? I draw on the distinction I have sketched here between deep and surface ideas of nature to argue that both nature-endorsing and nature-sceptical perspectives need to be more conscious of what their respective discourses on nature may be ignoring or politically evading. Just as a simplistic endorsement of the independent reality and intrinsic value of nature can seem insensitive to the concerns motivating the nature-sceptics, so an exclusive attention to the cultural construction of nature can very readily appear evasive of ecological realities and irrelevant to the task of addressing them. In developing this critique, I argue for an understanding of humanity-nature relations that I describe as both realist and humanist.

My realism consists in recognizing the difference between, and respective validity, of nature in both these understandings: there is both the nature that precedes all human activity and always enables and limits our operations; and a nature that only has the form or cultural presence it has in virtue of our activities, interventions and representations. My position is humanist, on the other hand, in the sense that it is opposed to the form of naturalism that wants to emphasise how similarly (rather than differentially) placed we are to other animals in respect of our essential needs and ecological dependencies and seeks to ground ecological policy in that recognition and I shall have more to say on this shortly. . From this perspective, I criticize the nature-sceptics for being too ready to deny or disregard the difference between nature conceived as permanent causal powers and its surface effects too ready, that is, to deny or abstract from the nature that is in play in all our human activities and responses, and whose laws we have to understand and observe in all our scientific applications, medical transformations, and projects in genetic engineering whether of the physical environment or of our own and other life-forms. In this sense they are wrong to claim that nature is invented or constructed. Nor can they make any claim to the effect that the nature-culture polarity is itself conventional which does not tacitly rely for its force on precisely that objectively grounded distinction between what is humanly instituted and what is 17

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07) naturally ordained, which is being rhetorically denied. When nature-sceptics insist upon the relative and arbitrary character of the nature-culture antithesis they are implicitly assuming what they purport to deny: that both terms have reference to distinguishable order of reality. Moreover, if there are, indeed, no natural needs, desires, instincts, dispositions, and so on, then it is difficult to see how these can be subject to the repressions or distortions of existing cultural norms, or be more fully

18

realized within some more emancipated social order. The skeptics are loathe to allow any reference to nature for fear of opening the floodgates to biological determinism. But to take all the conditioning away from nature and hand it to culture is to risk retrapping ourselves in a new form of determinism in which we are denied any objective ground for challenging the edict of culture on what is or is not natural. Such a position would mean in the end that it was only on the basis of personal, subjective preference (or prejudice) that we could contest the necessity of a practice such as female circumcision, denounce the oppression of sexual minorities or justify the condemnation of any form of sexual abuse. I suggest, then, that the ethical force of this form of nature scepticism is systematically undermined by the insistence on the arbitrary and purely politically determined character of the divide between the supposed givens of nature and the impositions of culture. Equally such antinaturalism is at odds with any ecological argument recalling us to our biological dependencies upon the eco-system. On the other hand, as I have already indicated there are several reasons to be cautious about opting for an unqualified nature-endorsement and its redemptive form of evaluation. As we have seen, it obscures the fact that much of the nature that we are called upon to preserve takes the form it does only in virtue of centuries of human activity (often abstracting in the process from the exploitative social relations which have gone into the making of the environment and are inscribed in its physical territory: in Britain, for example, in its grouse moors and enclosures, it feudal hamlets and country estates). But there are also serious ethical and political objections to conceptualizing nature as an autonomous locus of intrinsic value which we should always seek to preserve from human defilement and instrumental appropriation. To depict all human beings as equal enemies of nature is to abstract from the huge differences between the richer and the poorer nations in their consumption of global resources, and their levels of responsibility for ecological abuse. It can also condone policies of nature conservation whose effect is further to 18

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07)

19

reduce the livelihood of those more impoverished and exploited sectors of humanity who are least to blame for ecological depletion and also further remove them from the protection of living their lives in a more traditional, and, if you like, natural way. For it is one of the paradoxes of capitalist globalization that the more impoverished are ever further removed from the security and comforts of doing things in natures way, while the latter has often enough become the luxury of the richer and more privileged. As a result of the complex chain reactions set up by market relations, it is almost invariably the least economically advantaged who also become the most disadvantaged in respect to their access to nature construed in the sense of relatively unspoilt environment, purity of air, water and resources, and relatively unmediated biological process. 4 At the same time, - and here I am expanding on the humanist dimension of my argument - we need to be wary of the stress placed in this model of evaluation on the continuity or affinity between humans and other animals. Humanists like me who argue against basing ecological policy on the kinship between humans and other creatures are often accused of an anthropocentric prejudice against recognizing the extent of the coincidence between human and animal qualities, needs and ecological dependencies. But there is also something a touch anthropocentric in the readiness to assume that our human desires and capacities offer direct access to knowledge of their analogues in the worlds and lifestyles of other species. We do an injustice, moreover, to humankind in pretending to a unity or communality with other creatures that could be had only by denying or overlooking our more specifically human needs, concerns and qualities. As Andrew Ross has noted (Ross 1994b: 337), there is a slippery slope that runs from bio-centric ethics, wherein all life forms are equal, to the diminution of our hard-won social rights and freedoms, no sooner achieved than transferred elsewhere, to agents seen as more worthy because they are closer to nature. Ideally, maybe, the stewardship concept should be extended to include non-human life forms. But if recommendations

A striking instance is provided by Nancy Scleper-Hughes study (1992) of the modernization of infant mortality in the favelas, or slums, of the Brazilian sugar-planatation region. Deaths from diarrhoe due to unhygienic bottle-feeding would be largely preventable were the women to return to breast-feeding, but this is now made almost impossible for a number of complex, market-related reasons: loss of faith in the purity of breast-milk as a consequence of aggressive and medically inflected advertisement for manufactures formulas; the newly emergent practice for fathers to make a gift of tinned milk to the mother as a token of accepting paternal responsibility, and thus legitimising the child; the total lack of on the job breast-feeding capacities in the factories in which the women are employed. (Cf. Haraway, 1997: 202-212).

4

19

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07)

20

of this kind are not to remain purely abstract and regulative, it is important to consider how they might translate into more concrete policy-making and it is at that point that all the really difficult considerations about the ranking of different species and forms of concern, and the relative prioritisation of human and non-human needs and interests, must come to the fore as requiring attention.

20

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07) Bibliography Bailey, M. E. Foucauldian Feminism: contesting bodied, sexuality and identity in Ramazanoglo, C. (ed.) Up Against Foucault, London: Routledge, pp. 99-122. Bordo, S. (1990) Feminism, Postmodernism, and Gender-Skepticism, in L. Nicholson, (ed.), Feminism/Postmodernism, London: Routledge. Boulton, J. (ed.) (1958) Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Broadhurst Dixon, J. and Cassidy, E.J. (eds.) (1998) Virtual Futures: Cyberotics, Technology and Post-Human Pragmatism, London: Routledge.

21

Burke, E. (1756) A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. Reprinted in J. Boulton (ed.) (1958) Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Butler, J. (1990) Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, London: Routledge. ____ (1993) Bodies that Matter: on the Discursive Limits of Sex, London:

Routledge. Giddens, A. (1994) Beyond Left and Right: the Future of Radical Politics, Polity Press, Oxford Gray, C. H. (ed.) (1995) The Cyborg Handbook, London: Routledge. Haraway, D. (1991) Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, London: Free Association, Routledge. (1997) ModestWitness@Second Millennium: FemaleMan Meets OncoMouse, London and New York: Routledge. Hardt, M. and Negri, A. (2000) Empire, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Kant, I. ([1790] 1987) Critique of Judgement, trans., with an intro., by W. S. Pluhar, Indianapolis: Hackett. Latour, B. (1998) To Modernize or Ecologize ? in Castree, N. and Williams-Braun, B. (eds.) Remaking Reality: Nature at the Millenium, London: Routledge. MacDowell, J. (1996) Mind and World, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. MacNaghten, P. and Urry, J. (1998) Contested Natures, Sage, London. Marx, K. (1968) The German Ideology, Progress Publishers: Moscow. Monk, S. H. (1935) The Sublime: A Study of Critical Theories in the 18th Century, Ann Arbor: Michigan University Press. 21

Kate Soper Lecture I for the British Council in Hungary ( 25.01.07) Nicolson, M. (1958) Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory, New York: Ithaca University Press. Peperell, R. (1995) The Post-Human Condition, Exeter: Intellect Books. Ross, A. (1994a) The Chicago Gangster Theory of Life, Natures Debt to Society, London: Verso.

22

(1994b) The New Smartness, in G. Bender and T. Druckrey (eds), Culture on the Brink: Ideologies of Technology, Seattle: Bay Press. Poster, M.(1996) Postmodern Virtualities in Lisa Tickner et alii (eds.) Future/Natural, London: Routledge, pp. 183-202. Plant, S. (1996) The Virtual Complexity of Culture in Lis Tickner et alii (eds.) Future/Natural, London: Routledge, pp. 203-217. Scleper-Hughes, N. Death without Weeping: the Violence of Everyday Life in Brazil, Los Angeles: University of California Press. Soper, K. (1995) What is Nature? Culture, Politics and the Non-Human, Oxford: Blackwell. (1996) A Green Mythology, Capitalism, Nature, Socialism, 7(3): 119125. (1997) Human Needs and Natural Relations: the Dilemmas of Ecology I, Capitalism, Nature, Socialism, 8(4): 5965. (1999) Of OncoMice and FemaleMen: Donna Haraway on Cyborg Ontology, Women, a Cultural Review, 10(2): 167172. (2003) Humans, Animals, Machines, New Formations, 49: 99109. Tuveson, E. L. (1960) The Imagination as a Means of Grace, Berkeley: Berkeley University Press. Wilson, A. (1992) The Culture of Nature: North American Landscazpe from Disney to the Exxon Valdez, Oxford: Blackwell.

22

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Reading Arabic For BeginnersDocument48 pagesReading Arabic For BeginnersARRM87MURUGANNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- (Richard Levins) Theory of Fitness in A Heterogene PDFDocument67 pages(Richard Levins) Theory of Fitness in A Heterogene PDF5705robinNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Clues by Carlo GinzburgDocument16 pagesClues by Carlo Ginzburg5705robinNo ratings yet

- Heidegger - Being and TimeDocument540 pagesHeidegger - Being and Timeparlate100% (3)

- Ethics G1 - Divine Command Theory and Natural Law TheoryDocument4 pagesEthics G1 - Divine Command Theory and Natural Law TheoryJim Paul ManaoNo ratings yet

- TEACHER APPLICANT DARWIN BAJAR SEEKS TEACHING POSITIONDocument4 pagesTEACHER APPLICANT DARWIN BAJAR SEEKS TEACHING POSITIONDarwin BajarNo ratings yet

- Career Development Program ProposalDocument9 pagesCareer Development Program Proposalapi-223126140100% (1)

- Compound Interest CalculatorDocument4 pagesCompound Interest CalculatorYvonne Alonzo De BelenNo ratings yet

- Thesis With BoarderDocument26 pagesThesis With BoarderFernando CruzNo ratings yet

- Prashob Print NumberDocument54 pagesPrashob Print Number5705robinNo ratings yet

- Toward An Ecological Definition of An Island: A Northwest European Perspective Haila, YrjoDocument9 pagesToward An Ecological Definition of An Island: A Northwest European Perspective Haila, Yrjo5705robinNo ratings yet

- Hockney To Hogarth Resource1Document26 pagesHockney To Hogarth Resource15705robinNo ratings yet

- Zizek On Law by Jodi DeanDocument24 pagesZizek On Law by Jodi Dean5705robinNo ratings yet

- Just An Image: Godard, Cinema, and Philosophy Marcia LandyDocument23 pagesJust An Image: Godard, Cinema, and Philosophy Marcia Landy5705robinNo ratings yet

- Zizek On Law by Jodi DeanDocument24 pagesZizek On Law by Jodi Dean5705robinNo ratings yet

- (Zizek Slavoj) From History and Class ConsciousnesDocument18 pages(Zizek Slavoj) From History and Class Consciousnes5705robinNo ratings yet

- Witkin, Robert W. (2000) - Why Did Adorno Hate Jazz, in Sociological Theory, Vol. 18, Nº 1, 145-170Document27 pagesWitkin, Robert W. (2000) - Why Did Adorno Hate Jazz, in Sociological Theory, Vol. 18, Nº 1, 145-170jcosta67No ratings yet

- Ankersmit's Postmodernist Historiography: The Hyperbole of "Opacity" John H. ZammitoDocument17 pagesAnkersmit's Postmodernist Historiography: The Hyperbole of "Opacity" John H. Zammito5705robinNo ratings yet

- Synthesizing Gauguin: A Comparative Look at Cultural Contexts and Gauguin's Tahitian Paintings PDFDocument61 pagesSynthesizing Gauguin: A Comparative Look at Cultural Contexts and Gauguin's Tahitian Paintings PDF5705robinNo ratings yet

- Bf01298417) Ananta Kumar Giri - The Dialectic Between Globalization and Localization - Economic Restructuring, Women and Strategies of Cultural ReproductionDocument24 pagesBf01298417) Ananta Kumar Giri - The Dialectic Between Globalization and Localization - Economic Restructuring, Women and Strategies of Cultural Reproduction5705robinNo ratings yet

- Eco ModernizationDocument7 pagesEco ModernizationAbhilash ChandranNo ratings yet

- A-1011615201664) Tom Brass - Nymphs, Shepherds, and Vampires - The Agrarian Myth On FilmDocument34 pagesA-1011615201664) Tom Brass - Nymphs, Shepherds, and Vampires - The Agrarian Myth On Film5705robinNo ratings yet

- 1360-1385 (96) 89239-9) Roy Ellen - Plants and PeopleDocument1 page1360-1385 (96) 89239-9) Roy Ellen - Plants and People5705robinNo ratings yet

- Aa.1996.98.2.02a00150) Rena Lederman - Anti Anti "Anti-Science"Document3 pagesAa.1996.98.2.02a00150) Rena Lederman - Anti Anti "Anti-Science"5705robinNo ratings yet

- 453154a) Smil, Vaclav - Long-Range Energy Forecasts Are No More Than Fairy TalesDocument1 page453154a) Smil, Vaclav - Long-Range Energy Forecasts Are No More Than Fairy Tales5705robinNo ratings yet

- The Bond Phenomenon:theorizing A Popular Hero by Tony BennettDocument31 pagesThe Bond Phenomenon:theorizing A Popular Hero by Tony Bennett5705robinNo ratings yet

- 3 Sources N 3 Component Parts of Marxism by LeninDocument42 pages3 Sources N 3 Component Parts of Marxism by Lenin5705robinNo ratings yet

- 0037-7856 (75) 90182-1) Lawrence G. Miller - Negative TherapeuticsDocument5 pages0037-7856 (75) 90182-1) Lawrence G. Miller - Negative Therapeutics5705robinNo ratings yet

- 3178065) Longino, Helen E. Keller, Evelyn Fox Fausto-Sterling, Anne Ha - Science, Objectivity, and Feminist ValuesDocument15 pages3178065) Longino, Helen E. Keller, Evelyn Fox Fausto-Sterling, Anne Ha - Science, Objectivity, and Feminist Values5705robinNo ratings yet

- 0169-5347 (96) 20079-5) Paul R. Ehrlich - Environmental Anti-ScienceDocument1 page0169-5347 (96) 20079-5) Paul R. Ehrlich - Environmental Anti-Science5705robinNo ratings yet

- 0169-5347 (96) 20079-5) Paul R. Ehrlich - Environmental Anti-ScienceDocument1 page0169-5347 (96) 20079-5) Paul R. Ehrlich - Environmental Anti-Science5705robinNo ratings yet

- j.1741-5446.1980.Tb00934.x) Timothy Reagan - The Foundations of Ivan Illich ' S Social ThoughtDocument14 pagesj.1741-5446.1980.Tb00934.x) Timothy Reagan - The Foundations of Ivan Illich ' S Social Thought5705robinNo ratings yet

- Bf00156400) Rod Aya - Theories of Revolution ReconsideredDocument61 pagesBf00156400) Rod Aya - Theories of Revolution Reconsidered5705robinNo ratings yet

- j.1460-2466.1974.Tb00404.x) Stuart Hall - Media Power - The Double BindDocument8 pagesj.1460-2466.1974.Tb00404.x) Stuart Hall - Media Power - The Double Bind5705robinNo ratings yet

- 0305-750x (76) 90082-6) Vaclav Smil - Intermediate Energy Technology in ChinaDocument9 pages0305-750x (76) 90082-6) Vaclav Smil - Intermediate Energy Technology in China5705robinNo ratings yet

- Comparing Trotskyism and Maoism in France and the USDocument20 pagesComparing Trotskyism and Maoism in France and the US5705robin100% (1)

- 148411a0) NEEDHAM, JOSEPH - The Relations Between Science and EthicsDocument1 page148411a0) NEEDHAM, JOSEPH - The Relations Between Science and Ethics5705robinNo ratings yet

- Philo 1 Week 1Document12 pagesPhilo 1 Week 1Cherie ApolinarioNo ratings yet

- Combine Group WorkDocument32 pagesCombine Group WorkTAFADZWA K CHIDUMANo ratings yet

- Rickford The Creole Origins of African American Vernacular EnglishDocument47 pagesRickford The Creole Origins of African American Vernacular EnglishAb. Santiago Chuchuca ZambranoNo ratings yet

- Cot Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesCot Lesson PlanBlessel Jane D. BaronNo ratings yet

- English Language Skills Course StructureDocument3 pagesEnglish Language Skills Course StructureyourhunkieNo ratings yet

- GSM MBA admission requirementsDocument2 pagesGSM MBA admission requirementsyoulbrynerNo ratings yet

- Governing The Female Body - Gender - Health - and Networks of Power PDFDocument323 pagesGoverning The Female Body - Gender - Health - and Networks of Power PDFMarian Siciliano0% (1)

- reviewer ノಠ益ಠノ彡Document25 pagesreviewer ノಠ益ಠノ彡t4 we5 werg 5No ratings yet

- House of Wisdom BaghdadDocument16 pagesHouse of Wisdom BaghdadMashaal Khan100% (1)

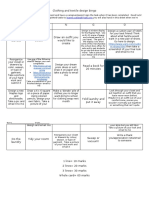

- Clothing and Textile Design BingoDocument2 pagesClothing and Textile Design Bingoapi-269296190No ratings yet

- Genres of LiteratureDocument9 pagesGenres of LiteratureRochelle MarieNo ratings yet

- Information and Communications Technology HandoutsDocument7 pagesInformation and Communications Technology HandoutsMyrna MontaNo ratings yet

- Class Struggle and Womens Liberation PDFDocument305 pagesClass Struggle and Womens Liberation PDFAsklepios AesculapiusNo ratings yet

- REFORMS Zulfiqar AliDocument3 pagesREFORMS Zulfiqar AliHealth ClubNo ratings yet

- SOC220 Sched Fa 11Document1 pageSOC220 Sched Fa 11Jessica WicksNo ratings yet

- Can reason and perception be separated as ways of knowingDocument2 pagesCan reason and perception be separated as ways of knowingZilvinasGri50% (2)

- CMR Institute soft skills syllabusDocument2 pagesCMR Institute soft skills syllabusSachin GNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature GenresDocument10 pagesPhilippine Literature GenresWynceer Jay MarbellaNo ratings yet

- BSHF 101 emDocument7 pagesBSHF 101 emFirdosh Khan91% (11)

- CAPE 2003 Caribbean StudiesDocument11 pagesCAPE 2003 Caribbean Studiesmjamie12345No ratings yet

- M.A. Mass Communication AssignmentsDocument10 pagesM.A. Mass Communication AssignmentsSargam PantNo ratings yet

- Related Reading 1 Literature During Spanish Era (Vinuya 2011)Document1 pageRelated Reading 1 Literature During Spanish Era (Vinuya 2011)Dwight AlipioNo ratings yet

- The Role of Transformational Leadership and Organizational Culture in Service Delivery Within A Public Service OrganizationDocument8 pagesThe Role of Transformational Leadership and Organizational Culture in Service Delivery Within A Public Service OrganizationonisimlehaciNo ratings yet