Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rhythm and Tempo

Uploaded by

niticdanOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rhythm and Tempo

Uploaded by

niticdanCopyright:

Available Formats

September Blog

Rhythm and tempo One of the most influential elements of music that affects interpretation is the treatment of rhythm and tempo. The slightest and subtlest changes of tempo can create an incredible change of the character of a piece. Rhythm can also be a difficult phenomenon to comprehend, as what we see on the page does not literally translate into sound. Guitarists, including myself, can tend to somewhat lack understanding in this area, as we often play so much solo repertoire. When one listens to an accomplished guitarist (say Julian Bream), there is always a sense of understanding regarding rhythm and tempo. This understanding plays a large role in the level of conviction of an interpretation. Here are some useful tips Ive picked up along the way of studying and hopefully some of them can be of some use to you!

Rubato Rubato is one of the easiest expressive rhythmic devices to become habitual. When we first learn a piece, particularly one were not familiar with, it may be very tempting to try and be expressive and tamper with the rhythmic structure of the piece in the process. So here are some strategies that Ive found helpful for avoid this kind of rubato. Playing with other musicians This is important, not just for developing a good sense of rhythm and tempo, but also for many other musical reasons. Try and play with other musicians as often as possible, even if its just a bit of fun sight-reading can be a great test of your rhythmic abilities! Contacting your local guitar society can be a good way of finding some peers to play with. (The Classical Guitar Society of Victoria is a good place to start if you live in Victoria) Practicing with a metronome This is something that can often be misunderstood. The metronome is often used for building up tempo, but that is definitely not the only thing they can be useful for. These days, with the development of electronic metronomes, you can apply many different settings that are easy to program into the metronome.

Light only Most electronic metronomes have the function of beating time with just a flashing light. If it doesnt then theres probably a way of turning down the volume while keeping the light on. Using the metronome in this way means that you dont rely on the beat being beaten aurally. You instead rely more on your visual sense, meaning that your bodily rhythmic awareness is being expanded to another sense. Its something more similar to following a conductor in a sense (a rather emotionless one!). There is something valuable in trying to land your beat with a visual cue rather than an aural one. At the very least it will provide a difference of approach that will be a good test of your rhythmic control.

Off beat Metronomes usually have a different type of click for the downbeat and offbeat and you can use this to your advantage. It can be useful to practice on the offbeat as we so often feel the downbeat as our principle pulse. The offbeat is also a feature in a lot of works composed for the guitar, particularly ones influenced by folk elements. There are often rests or no re-articulations on the offbeats, which can make it tempting to rush or lose sense of the pulse. Pulse is created by a sense of strong and weak beats and the offbeats can be thought of as weak beats. This doesnt mean that the weak beats are less important than the strong in fact they deserve equal attention, and a performers understanding of this can help establish a deeper level of rhythmic interpretation. Practicing in a way that emphasises the offbeats can help enhance this sense of rhythm. Here is one example where this can apply from the final section of a piece Ive been playing for a while, the Hungarian Fantasy by J.K. Mertz

Subdivisions Metronomes usually have a function to change the subdivision of the beat from crochet to semiquaver. My metronome (a Dr. Beat) has these subdivions and it can be useful to apply some different ones as they can give a certain rhythmic feel to what youre playing

On/off Ive mentioned this idea briefly before in other blogs and Ive found it to be a very good way of using the metronome. Play with the metronome once then play again without. Do this a few times to really make sure your rhythm doesnt fluctuate in ways you dont want it to. Mark in your score where you want to use rubato or broaden or ritardando etc.

Polyrhythms This can be very useful for practicing changes of subdivision, such as from semiquavers to quaver triplets. Put the metronome on semiquaver and play triplets and vice versa. This can be a great rhythmic study and I find it can get quite grooooovy after a while. Time words Metronomes often have time words (such as adagio, andante, allegro, etc.) attached to the numbers, so its worth putting some thought into this aspect. Sometimes it can be effective to practice a piece or passage at a different time word than what is marked in the score. Often it is the editor that has indicated the time word, so its not always the definitive option. Choose a tempo that suits your taste and needs and that you feel suits the character that you are trying to convey. This may change from time to time, but its always worth consciously experimenting with tempo. Sometimes it can be hard to put a number to a specific time word an adagio in one piece may be quite a lot faster or slower than an adagio in another! If there is no time word marked, then youll probably have to briefly analyse certain elements such as phrasing, harmonic rhythm and rhythmic subdivisions (i.e. if there are demisemiquavers then that will probably affect your tempo decision). Its also worth investigating what the different time words mean. For example, allegro doesnt just necessarily mean fast it also usually implies sprightliness or cheerfulness.

Slow/fast This is related to the on/off approach mentioned earlier. This one speaks for itself play a passage slow (maybe half tempo), and then play it at tempo immediately after. I find its good to do it slow again immediately after, so I finish with good habits - so thats, slow/fast/slow (fast meaning at tempo or close to). You can also do the reverse fast/slow and/or fast/slow/fast.

Rhythmic phrasing Rhythmic phrasing can be though of in similar terms to melodic phrasing. I like to think of phrasing as being the lingual equivalent of grouping letters into words, sentences and paragraphs. Once phrasing has been interpreted, then the individual pitches and rhythms should make sense and unite to create musical coherence - or in lingual equivalence, will form a kind of narrative or story. Another important aspect of phrasing for me is the idea of inflection. This also

ties in closely to language and narrative, particularly speech. Once a phrase has been defined, you can try playing it with different inflections. Sometimes adding words or lyrics to a phrase can help further define the kind of inflection you think best suits the character of the phrase or piece. The lyrics you choose can also help add to the character of the piece, for example a piece that could be interpreted to have a cheerful character (1st mvt. of Sonatina in A by Torroba could be an example) could have lyrics that could also portray a cheerful character. Lets take a further look at the rhythmic phrasing of the beginning of the 1st movement of Sonatina in A by Torroba.

Firstly I think its important to identify any recurring rhythmic patterns and the next example makes this a bit clearer -

In the example above Ive reduced the rhythm to one pitch (you can actually practice it like this too!). The different octaves represent the different rhythmic elements or voices of the example. Observe the different stemmings of the different voices in the original example. This is not just an important factor melodically, but rhythmically as well.

A fairly large proportion of the movement uses this opening rhythmic phrase, or variations of the different elements at least. Again, identifying these types of repeated patterns is very useful for interpreting the rhythmic elements of the structure it also makes learning the piece much faster too! In order to create rhythmic phrasing, I use some of the devices mentioned before. The first thing that I will usually consider is the indicated time word Allegretto. This word derives from Allegro, which can be literally translated to cheerful, merry and/or jolly. In terms of tempo allegretto is somewhere in-between allegro and andante (I think andante derives from the word andare, which can translate to something like to walk, or in terms of tempo, at a walking pace). So how does the allegretto get conveyed through rhythm? This passage is beautifully devised to convey the sense of allegretto and Ill show a clearer diagram to demonstrate the rhythmic elements of this

From the very beginning, Torroba establishes a sense of rhythmic vitality by placing a strong chord on the first beat. Many pieces often start with some kind of upbeat, which creates a sense of weak to strong. Here, Torroba does the reverse and starts with a strong pulse. Straight after this the main rhythmic subject is introduced. We can break this down even further

Notice that in the third group this grouping across the bar line is supported by the bass another rhythmic layer. This gives the rhythmic phrase a kind of comma, a signal of finishing that group. Following this is a kind of response that uses very similar kinds of groups in fact it is virtually an exact repetition rhythmically. To me, the rhythmic vitality is created by these repeating groups and is supported by melodic sequences and repetitions. By observing these patterns, a different kind of understanding of the musics structure and character will be found and this will often result in learning pieces much faster.

Solving rhythmic complexities Sometimes rhythms can be found that are just plain difficult to execute accurately and with control. As a result they can come across in an undesired way. Here is one that is not too complex, but caught me off guard when learning the piece. From the Homage pour le Tombeau Debussy by Manuel de Falla

For me there are several rhythmic challenges about these three bars. The first bar alone presents itself with two different challenges going from demisemiquavers to sextuplets and from septuplets to semiquavers. There are a few procedures I use to help keep my sense of tempo and rhythm clear. Most of these tactics involve simplifying the rhythm in some way. The first thing Id probably do is practice something like this

As you can see, all Ive done is left out the sextuplet figure, taking out the most complex element. Other similar procedures are things like outlining, whereby you just play the first beats of each complex group

While doing work like this, it is good to also visualize and/or hear whatever is left out. The transition from quavers to sextuplets (bars 2 3 of the example) can also be practiced in similar ways. This kind of work is also great for memorization - the topic of next months blog.

For further reading/study I recommend Ear Training by Jorgen Jersild Solfeggi parlati e cantati (spoken and singing solfege) by Pozzoli (any solfege book will probably do)

You might also like

- Modes and Ragas More Than Just A Scale 16Document10 pagesModes and Ragas More Than Just A Scale 16Ahmed Hawwash100% (1)

- The Sonata, Continued: The Other Movements: Theme and VariationsDocument9 pagesThe Sonata, Continued: The Other Movements: Theme and Variationsnyancat009No ratings yet

- Daily Pract RoutDocument1 pageDaily Pract RoutCol BoyceNo ratings yet

- Basic Music Theory For Beginners - The Complete GuideDocument21 pagesBasic Music Theory For Beginners - The Complete GuidepankdeshNo ratings yet

- Principles of Expressive Playing PDFDocument12 pagesPrinciples of Expressive Playing PDFFelipe AfonsoNo ratings yet

- BlushdaDocument1 pageBlushdadrumer93No ratings yet

- Berklee 1 and 2 Stroke RollsDocument4 pagesBerklee 1 and 2 Stroke RollsvitNo ratings yet

- Review of Renaissance PeriodDocument10 pagesReview of Renaissance PeriodTyrone ResullarNo ratings yet

- 11 Stretching Exercises For Musicians - Focus - The StradDocument8 pages11 Stretching Exercises For Musicians - Focus - The StradCacau Ricardo FerrariNo ratings yet

- Bartók-Dance in Bulgarian Rhythm No. 4Document5 pagesBartók-Dance in Bulgarian Rhythm No. 4Giorgio Planesio100% (1)

- Characteristics of The BaroqueDocument3 pagesCharacteristics of The BaroqueOrkun Zafer ÖzgelenNo ratings yet

- History of Motown Record Label & Entrepreneurship LessonDocument6 pagesHistory of Motown Record Label & Entrepreneurship LessonDouglas BrunnerNo ratings yet

- Essential Latin Music GenresDocument3 pagesEssential Latin Music GenresGuitoThomasNo ratings yet

- Graduate Jazz Recital Explores Standards & Modern WorksDocument16 pagesGraduate Jazz Recital Explores Standards & Modern WorksGeoffrey DeanNo ratings yet

- Handouts in MusicDocument4 pagesHandouts in MusicRowela DellavaNo ratings yet

- Ralph Vaughan WilliamsDocument3 pagesRalph Vaughan WilliamsDavid RubioNo ratings yet

- Detailed Course Outline: An Introduction and OverviewDocument6 pagesDetailed Course Outline: An Introduction and OvervieweugeniaNo ratings yet

- ScarlattiDocument22 pagesScarlattiSergio Rodríguez MolinaNo ratings yet

- Rocks Worldwide EPKDocument13 pagesRocks Worldwide EPKRock MediaNo ratings yet

- Classical Music Is Al DenteDocument7 pagesClassical Music Is Al DentealxberryNo ratings yet

- Sevish - Rhythm and Xen - Rhythm and Xen - Notes PDFDocument9 pagesSevish - Rhythm and Xen - Rhythm and Xen - Notes PDFCat ‡100% (1)

- Quality of RepertoireDocument16 pagesQuality of RepertoireMichael CottenNo ratings yet

- Quinn Drum and Bass DissertationDocument12 pagesQuinn Drum and Bass Dissertationደጀን ኣባባNo ratings yet

- The Structures of Music MelodyDocument14 pagesThe Structures of Music MelodyCaleb NihiraNo ratings yet

- Q1-Music 8-Thailand & LaosDocument22 pagesQ1-Music 8-Thailand & LaosYbur Hermoso-MercurioNo ratings yet

- Indian MusicDocument12 pagesIndian Musicapi-283003679No ratings yet

- The Repertoire Is The Curriculum: Getting BackDocument29 pagesThe Repertoire Is The Curriculum: Getting Backapi-25963806No ratings yet

- Mapeh 3RDDocument29 pagesMapeh 3RDmarkNo ratings yet

- History of Western Music Final Course Reduce Size PDFDocument282 pagesHistory of Western Music Final Course Reduce Size PDFRimaNo ratings yet

- Symmetry in John Adams's Music (Dragged) 3Document1 pageSymmetry in John Adams's Music (Dragged) 3weafawNo ratings yet

- Igor Stravinsky: Aeros Vincent Bautista Abilene ReglosDocument18 pagesIgor Stravinsky: Aeros Vincent Bautista Abilene ReglosTheSAmeNonsenseNo ratings yet

- Repertorio PDFDocument533 pagesRepertorio PDFCleiton XavierNo ratings yet

- The Rudiments of Highlife MusicDocument18 pagesThe Rudiments of Highlife MusicRobert RobinsonNo ratings yet

- Renaissance to Romantic MusicDocument58 pagesRenaissance to Romantic MusicemmaNo ratings yet

- School Logo The Ohio State University Logo Title A Bibliography of Chamber Music and Double Concerti Literature For Oboe and ClarinetDocument161 pagesSchool Logo The Ohio State University Logo Title A Bibliography of Chamber Music and Double Concerti Literature For Oboe and ClarinetceciliaNo ratings yet

- Music of IndiaDocument4 pagesMusic of IndiaPhilip WainNo ratings yet

- SATB Choral Sheet Music Documents About Coconut Nut SongDocument2 pagesSATB Choral Sheet Music Documents About Coconut Nut SongArthur Levasco0% (2)

- History of Western Music Grout OutlineDocument9 pagesHistory of Western Music Grout Outlinedielan wuNo ratings yet

- Music in The Baroque EraDocument16 pagesMusic in The Baroque EraSheena BalNo ratings yet

- Boulez Reflections JudyDocument10 pagesBoulez Reflections JudyJailton Bispo100% (1)

- Unit PlanDocument18 pagesUnit Planapi-510596636100% (1)

- Khachaturian Piano ConcertoDocument1 pageKhachaturian Piano Concertochris_isipNo ratings yet

- Modernism and ImprovisationDocument3 pagesModernism and ImprovisationGary Martin RolinsonNo ratings yet

- Classical Music - Contemporary PerspectivesDocument254 pagesClassical Music - Contemporary PerspectivesCesarPeredoNo ratings yet

- Describe How Mozart Uses Sonata Form in The 1st Movement of The 41st SymphonyDocument5 pagesDescribe How Mozart Uses Sonata Form in The 1st Movement of The 41st Symphonykmorrison13No ratings yet

- North African Music 2Document24 pagesNorth African Music 2NessaladyNo ratings yet

- FLP10003 Zimbabwe MbiraDocument6 pagesFLP10003 Zimbabwe MbiratazzorroNo ratings yet

- Medieval Music TimelineDocument4 pagesMedieval Music TimelineGeorge PetreNo ratings yet

- Gaber Melodic Timpani TechDocument4 pagesGaber Melodic Timpani TechmalekungNo ratings yet

- Robert Breithaupt PDFDocument2 pagesRobert Breithaupt PDFPalinuro TalassoNo ratings yet

- PA1903 Module Guide PDFDocument11 pagesPA1903 Module Guide PDFLuis Carlos RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Music course descriptions and detailsDocument11 pagesMusic course descriptions and detailsMarisa KwokNo ratings yet

- History of MusicDocument7 pagesHistory of MusicNina RicciNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of The Rock and Pop Music IDocument8 pagesThe Evolution of The Rock and Pop Music InucielNo ratings yet

- Unit Study - Appalachian MorningDocument4 pagesUnit Study - Appalachian Morningapi-437977073No ratings yet

- Psicology of Musical Memory PDFDocument3 pagesPsicology of Musical Memory PDFRachmat MaulanaNo ratings yet

- Music of the Medieval Period (700-1400Document33 pagesMusic of the Medieval Period (700-1400Eric Jordan ManuevoNo ratings yet

- The Baroque Period - Chap19Document36 pagesThe Baroque Period - Chap19Ju DyNo ratings yet

- Etude No 02 PDFDocument2 pagesEtude No 02 PDFniticdanNo ratings yet

- VisualizationDocument7 pagesVisualizationniticdanNo ratings yet

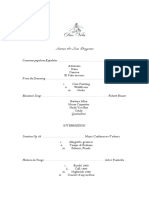

- Noche Espanola ProgramDocument2 pagesNoche Espanola ProgramniticdanNo ratings yet

- Regondi Etude 4 AnnotatedDocument2 pagesRegondi Etude 4 Annotatedniticdan100% (1)

- Classical Guitar ProgrammeDocument1 pageClassical Guitar ProgrammeniticdanNo ratings yet

- Adding Notes To Bach's Music On GuitarDocument1 pageAdding Notes To Bach's Music On GuitarniticdanNo ratings yet

- Enchanting World Music Duo VelaDocument1 pageEnchanting World Music Duo VelaniticdanNo ratings yet

- 18th & 19th Century GuitaristsDocument1 page18th & 19th Century GuitaristsniticdanNo ratings yet

- Article For Guitar On 19th C. Tone ColourDocument4 pagesArticle For Guitar On 19th C. Tone ColourniticdanNo ratings yet

- ProgramDocument1 pageProgramniticdanNo ratings yet

- Duo Vela Flute & Guitar Recital St Peter's Eastern HillDocument1 pageDuo Vela Flute & Guitar Recital St Peter's Eastern HillniticdanNo ratings yet

- Etude No 02 by Daniel NisticoDocument2 pagesEtude No 02 by Daniel Nisticoniticdan100% (1)

- Duo Vela Across The Seas ProgramDocument1 pageDuo Vela Across The Seas ProgramniticdanNo ratings yet

- CD SignDocument1 pageCD SignniticdanNo ratings yet

- Thoughts On The Left Hand On The Classical Guitar, Part 1, by Daniel NisticoDocument4 pagesThoughts On The Left Hand On The Classical Guitar, Part 1, by Daniel NisticoniticdanNo ratings yet

- Daniel Nistico CVDocument4 pagesDaniel Nistico CVniticdanNo ratings yet

- Duo Vela Online PresenceDocument6 pagesDuo Vela Online PresenceniticdanNo ratings yet

- Thoughts On The Left Hand On The Classical Guitar, Part 1, by Daniel NisticoDocument4 pagesThoughts On The Left Hand On The Classical Guitar, Part 1, by Daniel NisticoniticdanNo ratings yet

- Duo Vela Concert FlyerDocument1 pageDuo Vela Concert FlyerniticdanNo ratings yet

- Duo Vela Across The Seas ProgramDocument1 pageDuo Vela Across The Seas ProgramniticdanNo ratings yet

- Duo Vela Concert ProgramDocument9 pagesDuo Vela Concert Programniticdan100% (1)

- Tremolo Tips For The Classical GuitarDocument5 pagesTremolo Tips For The Classical Guitarniticdan75% (4)

- PHYS 105: Waves and OpticsDocument9 pagesPHYS 105: Waves and OpticsMaden betoNo ratings yet

- Carol of The Bells For String QuartetDocument2 pagesCarol of The Bells For String QuartetLucia Touriño100% (1)

- Moanin Art Blakey and The Jazz MessengersDocument16 pagesMoanin Art Blakey and The Jazz MessengersMaris MüllerNo ratings yet

- 2007.07 GrassDocument1 page2007.07 GrassWilliam T. PelletierNo ratings yet

- 3895111-I Can T Help Falling in Love With YouDocument2 pages3895111-I Can T Help Falling in Love With YouJackie Smith III100% (1)

- A Fair Judgement Tab With Lyrics by Opeth For Guitar at GuitaretabDocument4 pagesA Fair Judgement Tab With Lyrics by Opeth For Guitar at GuitaretabTodesengelNo ratings yet

- Peter Manuel - Popular Musics of The Non-Western World - An Introductory Survey-Oxford University Press (1988)Document328 pagesPeter Manuel - Popular Musics of The Non-Western World - An Introductory Survey-Oxford University Press (1988)Gunay KochanNo ratings yet

- Pernambuco and BowsDocument13 pagesPernambuco and Bowsnostromo1979100% (1)

- Noite Feliz-Pauta - e - PartesDocument12 pagesNoite Feliz-Pauta - e - PartesKarol GuimarãesNo ratings yet

- Your ManDocument5 pagesYour ManPaulino JoaquimNo ratings yet

- Finals Art App Quiz 15Document3 pagesFinals Art App Quiz 15Francesca Aurea MagumunNo ratings yet

- Bad RomanceDocument6 pagesBad RomanceKyeienNo ratings yet

- Ocean Eyes ChordsDocument3 pagesOcean Eyes ChordsSunny BautistaNo ratings yet

- Aamu Lakeuksilla - ScoreDocument1 pageAamu Lakeuksilla - ScoreAri TamminenNo ratings yet

- ShallowDocument3 pagesShallowdidrik sollihaugNo ratings yet

- Como é Grande o meu Amor por VocêDocument3 pagesComo é Grande o meu Amor por VocêFranciele SuskiNo ratings yet

- Mapeh 9Document5 pagesMapeh 9carmena b. oris100% (1)

- Sonic Spark: User ManualDocument4 pagesSonic Spark: User Manualprovocator74No ratings yet

- 2017-12 - The New YorkerDocument116 pages2017-12 - The New Yorkerafolleb100% (3)

- Reviewer 1ST GradingDocument23 pagesReviewer 1ST Gradingpretty raul100% (2)

- ITG Maurice AndreDocument13 pagesITG Maurice AndreNeburNo ratings yet

- NZrecommendedsolosDocument3 pagesNZrecommendedsolosAndres Garcia100% (1)

- Alex Dobrin: About The ArtistDocument2 pagesAlex Dobrin: About The ArtistTirdad SahlamalNo ratings yet

- Masa Sumide-SatoriDocument12 pagesMasa Sumide-SatoriJulienDebrouwerNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Insighter April 2023Document8 pagesIndigenous Insighter April 2023NBC MontanaNo ratings yet

- How KPOP Mirrors Gender RolesDocument26 pagesHow KPOP Mirrors Gender RolesButa UsagiNo ratings yet

- AISA's The Express: November 2010 (Vol. 1, No. 2)Document6 pagesAISA's The Express: November 2010 (Vol. 1, No. 2)StephenPBNo ratings yet

- AntlantisDocument7 pagesAntlantisirfanyNo ratings yet

- J74 Progressive Chord Editor GuideDocument23 pagesJ74 Progressive Chord Editor Guideen_motionNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument10 pagesUntitledmtNo ratings yet