Professional Documents

Culture Documents

An Interview With Christopher Alcantara

Uploaded by

NorthernPA100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

551 views5 pagesFrom Volume 1, Issue 3

Original Title

An interview with Christopher Alcantara

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentFrom Volume 1, Issue 3

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

551 views5 pagesAn Interview With Christopher Alcantara

Uploaded by

NorthernPAFrom Volume 1, Issue 3

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

14

Joshua Gladstone (JG): You spend considerable

time and energy writing and speaking about Indig-

enous-settler relations in Canada. Where does your

interest come from?

Chris Alcantara (CA): During my undergraduate

studies at McMaster University, my roommate, Ty

Hamilton, was completing a minor in Indigenous

studies and he would constantly talk about the com-

plex relationship between Indigenous and settler

peoples in Canada. It was a topic that I had really

no knowledge of despite doing a double major in

political science and history. But his insights really

got me interested in learning more about this topic.

When I got to Calgary to do my Masters degree,

I took a course on comparative Indigenous politics

with David E. Wilkins, who was at the University as

a visiting Fulbright scholar. That course, plus writ-

ing an M.A. thesis on property rights, Indigenous

poverty, and the Indian Act under the supervision

of Tom Flanagan, really got me interested in learn-

ing more about the Indigenous-settler relationship

in Canada.

JG: What motivateo you to write a book specincally

about comprehensive land claims agreements?

CA: As I learned more about the Indigenous-settler

relationship in Canada, I stumbled upon this grow-

ing literature on modern treaties and was fascinated

by the debate on whether modern treaties could be

used to effectively address the wretched conditions

found on some Indigenous communities. Some

commentators believed that modern treaties could

be used to achieve meaningful Aboriginal self-de-

termination and prosperity. Others thought that

modern treaties were simply another tool that the

Canadian state was using to co-opt Indigenous peo-

ples, lands, and priorities. I knew that I wanted to

contribute to this debate but I also knew I wasnt a

political theorist! So I thought my initial contribu-

tion to this debate could be to tackle the question of

why some Aboriginal groups were able to complete

modern treaties and why some have not. Lots of

people had ideas about the factors that generated

successful and unsuccessful negotiations, but none

had addressed this question systematically or com-

paratively.

JG: What problems are comprehensive land claims

agreements meant to solve for Indigenous groups?

Government?

CA: Originally, comprehensive land claims agree-

ments emerged in the early 1970s in response to

growing concerns about Indigenous mobilization

and some litigation that had established the legal

existence of Aboriginal title. In essence, the govern-

ment of Canada became concerned that Indigenous

peoples had legitimate ownership claims over cer-

tain Crown lands that had never been subject to his-

torical treaties with Indigenous peoples. To alleviate

this uncertainty, the federal government initiated

what it called comprehensive land claims negotia-

tions with those groups that had never signed treaties

with the Crown. So the original impetus for modern

treaties was the Crowns concerns about Indigenous

political mobilization and the lack of certainty and

nnality regaroing the ownership ol Canaoa`s lanos.

Over time, the negotiation process and the agree-

ments themselves have evolveo to renect a growing

desire to help Indigenous peoples achieve meaning-

ful political and economic self-determination and

prosperity. Defenders of modern treaties argue that

they provide Indigenous groups with a wide variety

of powers and jurisdiction over a range of lands.

Some also contain self-government provisions, em-

powering Indigenous groups to establish their own

self-governing regimes. Critics, on the other hand,

suggest that these supposeo benents are lar too limit-

ed in scope and that the costs of achieving them are

far too high for the Indigenous signatories.

IN CONVERSATION

Professor Chris Alcantara

Northern Public Affairs, Spring 2013

Professor Chris Alcantara spoke with our editor, Joshua Gladstone, in March

about his new book Negotiating the Deal: Comprehensive Land Claims

Agreements in Canada, published by University of Toronto Press.

Alcantaras book was published in March 2013 by University of Toronto Press.

JG: How effective do you think CLCs are in solving

these problems?

CA: Quite frankly, I dont know. The existing lit-

erature is divided on the utility of modern treaties

and so theres a real need for someone to do a seri-

ous, comparative and systematic study of modern

treaty implementation from a social science, Indig-

enous-centred, or hybrid perspective. As far as I

can tell, no one had yet to produce such a study but

hopefully someone will.

JG: In your forthcoming book, you ask why some

Indigenous groups have been able to complete com-

prehensive land claims agreements while others

have not. What have you found?

CA: The existing literature tends to argue that mod-

ern treaty negotiations are extremely slow because

the federal, provincial, and territorial governments

are too innexible ano oominating ouring negotia-

tions. Yet this explanation doesnt take into account

the fact that over 20 groups have completed modern

treaties. My book argues that the key to successful

and unsuccessful treaty negotiations lies with the

Aboriginal groups. It is true that the Crown is high-

ly innexible ano oominating ano that it holos much

of the power in the negotiation process. Indeed, the

federal, provincial, and territorial governments also

have considerable ownership rights and resources

at their disposal. But some Aboriginal groups have

completed modern treaties despite these facts and so

any explanation of treaty negotiations must take into

account the role of Aboriginal groups in the process.

So what does this mean in practice? Given that

the Crown dominates the treaty negotiation process,

Aboriginal groups that want to complete a compre-

hensive land claims agreements must convince the

Crown to oo so. Specincally, this means that Aborig-

inal groups must adopt negotiation goals that are

compatible with the goals of the federal, provincial,

and territorial governments. They must minimize

the use of confrontational tactics, which can be seen

as embarrassing lor government olncials. They must

forge internal cohesion as it relates to completing a

treaty and they must foster positive perceptions of

themselves among government olncials. Govern-

ments want to sign treaties with those groups that

they think are likely to be successful at treaty imple-

mentation because they do not want to deal with the

embarrassment ol Aboriginal nnancial mismanage-

ment or political corruptionin-nghting, post-treaty.

This explanation challenges much of the con-

ventional wisdom on treaty negotiations, which

tends to focus on the role of the Canadian govern-

ments and the need for a major economic develop-

ment opportunity to exist on Indigenous lands. My

research nnoings suggest these are important lac-

tors, but that you cant fully explain successful and

unsuccessful treaty negotiations without taking into

account the active role that Indigenous groups play

in the process. Of course, this active role is highly

constrained by a number of other factors, including

the actual negotiation environment, which was cre-

ated and is controlled by the Crown itself ! Another

potentially constraining lactor is the specinc histo-

ry of government interference in each Indigenous

community. Some groups, for instance, have strug-

gled to forge internal cohesion because the federal

or provincial governments imposed membership

rules on the community, or moved the community

from place to place without their consent, or under-

funded the community, among other things. And so

some groups have louno it oilncult to achieve the

necessary factors for treaty completion. But treaty

completion is not impossible. My research shows

that Indigenous groups can overcome these barriers

through the actions of their political leaders.

JG: This past September, the Government of Can-

aoa announceo a new approach to treaty nego-

tiations involving results-based negotiations and

the promotion of other tools to address Aboriginal

rights and promote economic development and

sell-sulnciency. Given the role you ascribe to Inoig-

enous groups in the treaty-making process, what do

you think the ellect ol this new approach might

be?

CA: When I saw the announcement in Fall 2012, I

was stunned! In my book, I dont make any policy

suggestions for reforming the negotiation process.

My primary goal was social scientinc in nature: to

simply identify the factors that led to completed and

incomplete treaty negotiations. Although the book

doesnt offer any suggestions for policy reform, it

does outline and analyze the various choices that

Inoigenous groups lace, given my nnoings ano the

lact that signincant policy relorm is unlikely to oc-

cur anytime soon. These choices incluoe: nno a way

to achieve the necessary strategies to complete a

modern treaty; choose one of several existing policy

alternatives to modern treaties (e.g. bilateral agree-

ments, incremental treaty agreements, self-govern-

ment, or legislative alternatives like the First Nations

Land Management Act); or stick with the status quo (e.g.

no treaty). The government of Canadas new ap-

proach seems to renect some ol the analysis in my

16 Northern Public Affairs, Spring 2013

17

book. As far as I can tell, the government of Can-

ada plans to focus its efforts on those groups that it

thinks can successfully complete negotiations while

encouraging other groups to pursue alternatives to

the treaty process, either as an end in of itself, or as a

means of building capacity towards eventual treaty

completion.

So what will happen as a result of these new

government reforms? I think negotiations will accel-

erate signincantly with those groups that are alreaoy

capable of completing negotiations (e.g. are close

to achieving the four necessary strategies). Other

groups will be encouraged to choose the status quo

(no treaty) or one of the alternative policy options

currently available. These alternatives will provide

opportunities for capacity building and for improv-

ing standards of living in Indigenous communities,

which in turn may help some groups convince the

government to complete treaty negotiations. But for

the majority of groups that are struggling to com-

plete negotiations, the reforms will probably not

help them complete modern treaties.

I remember several years ago sharing some of

my initial nnoings with several senior government

olncials. One ol them remarkeo that he thought

the nnoings woulo be uselul lor relorming the treaty

process. I never thought anything would come of it

but the announcement in the fall reminded me how

our research can sometimes have a signincant ellect

on public policy (assuming my work actually did

have any innuence,.

JG: When the Idle No More movement sprang up

across the country including in areas covered by

modern treaties it called attention to the deplor-

able conditions in many Indigenous communities

ano the acerbic nature ol Inoigenous-settler connict.

Are modern treaties part of the solution to these is-

sues, or part of the problem?

CA: I think modern treaties can be both. On the

one hand, modern treaties have the potential to

provioe Inoigenous communities with signincant

resources and jurisdictions to exercise meaningful

self-determination and economic prosperity. On

the other hand, even the best treaties can generate

negative outcomes! Much depends on whether the

government of Canada is willing to uphold its treaty

implementation obligations and whether Indigenous

leaders can connect and engage meaningfully with

their community members.

JG: Earlier on, you mention your relationship with

Tom Flanagan as your thesis supervisor. Profesor

Ilanagan is a controversial ngure, incluoing lor his

writing on Indigenous-settler relations. How has

Professor Flanagan shaped your thinking on Indige-

nous-settler relations, and what do you think his leg-

acy will be in the nelo?

CA: When I arrived at the University of Calgary in

2001 to do my Masters degree in political science, I

vowed not to work with Dr. Flanagan. I had read the

nrst chapter in First Nations? Second Thoughts during

the last year of my undergraduate degree and was

appalled! However, Rainer Knopff convinced me

to at least meet with Dr. Flanagan to discuss the

possibility of him supervising my M.A. thesis and

so I did. After presenting him with my ideas, all of

which were extremely broad and impossible to do,

he suggested three very doable projects and I chose

the one on Certincates ol Fossession. It turneo out

to be an excellent decision!

Tom has taught me several important things

over the years, all of which I learned indirectly from

interacting with him as a graduate student and lat-

er as a co-author. First, ask and investigate research

questions that are relevant to real-world problems

ano issues. My nrst real research project was on the

positive and negative effects of the various proper-

ty rights imposed on Indian reserves by the Indian

Act. That research has helped the government of

Canada and some Indigenous communities across

the country to engage in property rights reform and

improve housing and economic development condi-

tions on their lands.

Second, dont be afraid to defend unpopular or

controversial arguments in your research. First Na-

tions? Second Thoughts was controversial for a number

of reasons, mainly because it took a particular stand

that was critical of the dominant view about Indige-

nous-settler relations. As a result, many scholars and

commentators heavily criticized and dismissed his

work. Yet the book was important because it chal-

lenged these scholars and commentators to directly

address the types of concerns raised by Flanagan

and to think more carefully about the robustness of

their arguments. Indeed, its only through debate

and discussion can we properly sharpen our argu-

ments and determine whether they are in fact right!

Third, be willing to change your mind. People

paint Tom as a right wing or libertarian ideologue

who is incapable of changing his mind. Yet Tom

has always taught me, again indirectly, that being

a scholar means being willing to listen to rational

and reasonable arguments. Ultimately, we need to

be prepared to change our minds and to realize that

our arguments and research might be wrong! In

Northern Public Affairs, Spring 2013

First Nations? Second Thoughts, Flanagan states that he

doesnt believe in Aboriginal self-government. Ten

years later, in Beyond the Indian Act, he argues that Ab-

original self-government is necessary for improving

living conditions on Canadian Indian reserves. To

me, thats remarkable and admirable and as a result,

Ive always tried to be open to the possibility that my

research and views are wrong.

I hope his legacy will be to remind us all to be

open to discourse and dialogue, no matter how un-

popular it may be. Only through debate and discus-

sion can we discover how robust and true our ideas

and arguments really are.

Christopher Alcantara is the author of Negotiating the

Deal: Comprehensive Land Claims Agreements in

Canada, published by the University of Toronto Press. He is

Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at

Wilfrid Laurier University.

SUBSCRIBE TODAY!

Three issues for $28

(plus GST/HST where applicable)

First issue mails Summer 2013. Subscribe online at www.northernpublicaffairs.ca.

Mail to: Northern Public Affairs P.O. Box 517, Stn. B, Ottawa, ON CANADA K1P 5P6

Individual (Canada): $28.00

Individual (United States): $49.00

Individual (International): $58.00

Institutional (Canada): $150.00

Institutional (United States): $175.00

Institutional (International): $200.00

(check one)

___________________________________________

Name (please print)

___________________________________________

Address

___________________________________________

Community Territory/Province

___________________________________________

Country Postal Code

___________________________________________

Email address

(please include payment)

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Sample Nomination LetterDocument1 pageSample Nomination LetterEvi NidiaNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Supervision in NursingDocument24 pagesSupervision in NursingMakanjuola Osuolale John100% (1)

- The Philippine Professional Standards For School Heads (PPSSH) IndicatorsDocument11 pagesThe Philippine Professional Standards For School Heads (PPSSH) Indicatorsjahasiel capulongNo ratings yet

- Communication For Health EducationDocument58 pagesCommunication For Health EducationBhupendra Rohit100% (1)

- School Health ServicesDocument56 pagesSchool Health Servicessunielgowda80% (5)

- Psycho ArchitectureDocument33 pagesPsycho ArchitectureCodrutza IanaNo ratings yet

- LuckyrockDocument6 pagesLuckyrockNorthernPA100% (1)

- Special Issue 2014 - Revitalizing Education in Inuit NunangatDocument92 pagesSpecial Issue 2014 - Revitalizing Education in Inuit NunangatNorthernPANo ratings yet

- Mary Simon: A Time For Bold Action On Inuit EducationDocument4 pagesMary Simon: A Time For Bold Action On Inuit EducationNorthernPANo ratings yet

- Special Issue 2014 - Revitalizing Education in Inuit NunangatDocument92 pagesSpecial Issue 2014 - Revitalizing Education in Inuit NunangatNorthernPANo ratings yet

- Northern Public Affairs Special Issue 2013Document64 pagesNorthern Public Affairs Special Issue 2013NorthernPA100% (1)

- SPECADocument7 pagesSPECANorthernPANo ratings yet

- CCARG Letter To Arctic CouncilDocument2 pagesCCARG Letter To Arctic Councilgladstone_joshuaNo ratings yet

- Defining The North - Peter RussellDocument2 pagesDefining The North - Peter RussellNorthernPANo ratings yet

- From The Yukon ArchivesDocument4 pagesFrom The Yukon ArchivesNorthernPANo ratings yet

- Philosophy and Logic: Atty. Reyaine A. MendozaDocument19 pagesPhilosophy and Logic: Atty. Reyaine A. MendozayenNo ratings yet

- Beliefs, Practices, and Reflection: Exploring A Science Teacher's Classroom Assessment Through The Assessment Triangle ModelDocument19 pagesBeliefs, Practices, and Reflection: Exploring A Science Teacher's Classroom Assessment Through The Assessment Triangle ModelNguyễn Hoàng DiệpNo ratings yet

- Ipcrf Cover 2021Document51 pagesIpcrf Cover 2021elannie espanolaNo ratings yet

- Father ManualDocument5 pagesFather Manualapi-355318161No ratings yet

- CR 1993 Joyce ReynoldsDocument2 pagesCR 1993 Joyce ReynoldsFlosquisMongisNo ratings yet

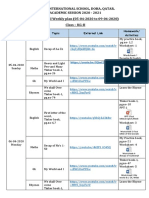

- Loyola International School, Doha, Qatar. Academic Session 2020 - 2021 Home-School Weekly Plan (05-04-2020 To 09-04-2020) Class - KG-IIDocument3 pagesLoyola International School, Doha, Qatar. Academic Session 2020 - 2021 Home-School Weekly Plan (05-04-2020 To 09-04-2020) Class - KG-IIAvik KunduNo ratings yet

- Course Syllabus: This Is Course Aims ToDocument3 pagesCourse Syllabus: This Is Course Aims ToYasser Abdel Galil AhmedNo ratings yet

- PLI March 2020Document19 pagesPLI March 2020Lex AmarieNo ratings yet

- Effects of Violent Online Games To Adolescent AggressivenessDocument20 pagesEffects of Violent Online Games To Adolescent AggressivenesssorceressvampireNo ratings yet

- Educational Scenario of Kupwara by Naseem NazirDocument8 pagesEducational Scenario of Kupwara by Naseem NazirLonenaseem NazirNo ratings yet

- TR HEO (On Highway Dump Truck Rigid)Document74 pagesTR HEO (On Highway Dump Truck Rigid)Angee PotNo ratings yet

- EDTECH 1 Ep.9-10Document17 pagesEDTECH 1 Ep.9-10ChristianNo ratings yet

- Uc Piqs FinalDocument4 pagesUc Piqs Finalapi-379427121No ratings yet

- Aparchit 1st August English Super Current Affairs MCQ With FactsDocument27 pagesAparchit 1st August English Super Current Affairs MCQ With FactsVeeranki DavidNo ratings yet

- EF3e Elem Filetest 12a Answer SheetDocument1 pageEF3e Elem Filetest 12a Answer SheetLígia LimaNo ratings yet

- PPUFrameworkDocument2 pagesPPUFrameworkAsmanono100% (2)

- The Constant Comparative Method of Qualitative AnalysisDocument11 pagesThe Constant Comparative Method of Qualitative AnalysisDani Ela100% (1)

- 156-Article Text-898-1-10-20230604Document17 pages156-Article Text-898-1-10-20230604Wildan FaisolNo ratings yet

- "Way Forward" Study Pack - English Grade Eight First Term-2021Document37 pages"Way Forward" Study Pack - English Grade Eight First Term-2021su87No ratings yet

- Republic of The Gambia: Ministry of Basic and Secondary Education (Mobse)Document43 pagesRepublic of The Gambia: Ministry of Basic and Secondary Education (Mobse)Mj pinedaNo ratings yet

- List of Schools For Special Children in PakistanDocument14 pagesList of Schools For Special Children in Pakistanabedinz100% (1)

- AssignmentB Step1 AdviceonAproachingThisAssignmentDocument4 pagesAssignmentB Step1 AdviceonAproachingThisAssignmentOckert DavisNo ratings yet

- Emcee ScriptDocument9 pagesEmcee ScriptChe Amin Che HassanNo ratings yet

- thdUdLs) 99eDocument1 pagethdUdLs) 99eHaji HayanoNo ratings yet