Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Roman Law

Uploaded by

nicoromanosOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Roman Law

Uploaded by

nicoromanosCopyright:

Available Formats

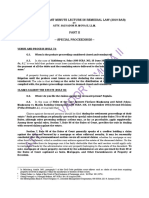

Book VI. Title XXIX. Concerning appointing posthumous children as heirs or disinheriting them or passing them over.

1 (De postumis heredibus instituendis vel exheredandis vel praeteritis.) Bas. 35.8.33. Headnote. The rule mentioned in the present title, too, is a stranger to the law in the United States. The Roman law required a testator to bear his children in mind when he made a testament. He was either required to appoint them as heirs or disinherit them. He could not pass them over in silence. That was just as true in the case of posthumous children, in which term all children born after the making of the will were included, as it was in the case of other descendants. If a son or other self-successor, male or female, born after the making of the will, was passed over in silence, the will, though originally valid, was invalidated by the subsequent birth of the child, and became completely void, even though the child died before the death of the testator. Male children were required to be disinherited expressly; females might be disinherited expressly or by a general clause; but if the latter mode was adopted, a legacy was required to be left them. Inst. 2.13.1. By C. 6.28.4.8, as we have seen, both males and females were required to be disinherited expressly, if disinherited at all, and the provision for a legacy above mentioned, was, therefore, repealed. 6.29.1. Emperor Antoninus to Brittianus. If after the making of a testament in which the testator has made no mention of posthumous children, a daughter was born to him, he died intestate, since a testament is broken by the birth of a posthumous child of which no mention is made, and the law is clear that no debt or claim can arise out of a testament which is broken. Given and Promulgated June 28 (213). 6.29.2. Emperors Diocletian and Maximian and the Caesars to Saterichus. It is clear law that the testament of a husband is not broken through a miscarriage of his wife; but when a posthumous child (that lives) although it immediately dies, is passed over, the broken testament is not reinstated. Subscribed at Sirmium February 20 (294). 6.29.3. Emperor Justinian to Julianus, Praetorian Prefect. We have decided a point in dispute among the ancients. When a descendant, carried in the womb of its mother, was passed over, and the could would, if it saw the

[Blume] A posthumous child included one born after the making of a testament. 9 Hugo Don. 323.

light of day, be heir to its father, and no one else would have precedence over it2, and it, by birth, would (ordinarily) have caused a testament to be broken, it was doubted whether if such posthumous child was indeed brought into the world, but died without emitting a sound, it could cause the testament to be broken. 1. The ancients were divided in their opinion as to what was to be said of the parents' will. The Sabinians thought that if the child was born alive, the testament was broken, though it uttered no sound, which too, would be true if it had been dumb. We commend their opinion and ordain that if it was born completely alive, tho it died immediately after coming to this earth, or in the hands of the midwife, the testament will, nevertheless, be void, provided only that it arrived in this world as a human being and not as a monster or prodigy. Given at Constantinople. 6.29.4. The same Emperor to Julianus, Praetorian Prefect. Someone, in making his testament, used these words: "If a son or daughter of mine shall be born within ten months after my death, let them be heirs," or stated as follows: "A son or daughter of mine, who is born within ten months next after my death, shall be my heirs." A dispute arose among the ancient interpreters of the law, whether (children born during the lifetime of the testator) would seem not to have been contemplated in the testament, and that this would be broken (by their birth).3 Since we have made many laws aiding the wishes of testators, we, in deciding this dispute, direct that the testament shall be effective, not withstanding the use of either of these phrases, and the testator's intention shall be upheld whether a son or daughter are born during the testator's lifetime or within ten months from the time of the testator's death, so that no testator who did not in fact overlook his children, suffer the penalty of doing so. Given at Constantinople November 20 (530).

[Blume] If a father is a living heir, a grandchild need not be disinherited. 9 Hugo Donellus 324. 3 This reflects changes penciled in by Blume. The typewritten original reads (after the first set of parentheses): ...were contemplated in the testament, or they would (by their birth) nullify it.

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Trajano V Uniwide SalesDocument2 pagesTrajano V Uniwide SalesGillian CalpitoNo ratings yet

- Sebastian vs. Atty. Bajar, A.C. No. 3731, September 07, 2007Document1 pageSebastian vs. Atty. Bajar, A.C. No. 3731, September 07, 2007You EdgapNo ratings yet

- 001 Sagrada Orden v. National Coconut Corporation (1952)Document2 pages001 Sagrada Orden v. National Coconut Corporation (1952)ALYNo ratings yet

- W11-Module 012 Ethics Through Thick and Thin - Aristotle On VirtueDocument3 pagesW11-Module 012 Ethics Through Thick and Thin - Aristotle On VirtueIvan BelarminoNo ratings yet

- SJS Officers v. Mayor Lim - Case DigestsDocument4 pagesSJS Officers v. Mayor Lim - Case DigestsJJMO100% (1)

- EYIS Vs SHENDAR - EfsarmientoDocument2 pagesEYIS Vs SHENDAR - EfsarmientoLizzette Dela PenaNo ratings yet

- REM Part II SPECPRO 2019 Last Minute PDFDocument12 pagesREM Part II SPECPRO 2019 Last Minute PDFtornsNo ratings yet

- MA Family Institute Amicus Brief - Mass DOMA CasesDocument33 pagesMA Family Institute Amicus Brief - Mass DOMA CasesKathleen PerrinNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law 1: University of San Jose Recoletus Cebu City Atty. Gonzalo D. Malig-On, JRDocument51 pagesConstitutional Law 1: University of San Jose Recoletus Cebu City Atty. Gonzalo D. Malig-On, JRCates TorresNo ratings yet

- 14 Neri Vs YusopDocument3 pages14 Neri Vs YusopJessa LoNo ratings yet

- Rti PPTDocument28 pagesRti PPTadv_animeshkumar100% (1)

- VI - Bill of Rights (ART. 3)Document50 pagesVI - Bill of Rights (ART. 3)Munchie MichieNo ratings yet

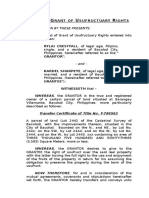

- Sample Deed of Usufruct Over A Real Property PDFDocument5 pagesSample Deed of Usufruct Over A Real Property PDFNur Azlin IsmailNo ratings yet

- Prepared For: Lecturer's Name: Ms. Najwatun Najah BT Ahmad SupianDocument3 pagesPrepared For: Lecturer's Name: Ms. Najwatun Najah BT Ahmad SupianBrute1989No ratings yet

- Skeleton Argument of The Plaintiff/Appellant: 1 (2011) EWCA Civ 133Document6 pagesSkeleton Argument of The Plaintiff/Appellant: 1 (2011) EWCA Civ 133k_961356625No ratings yet

- 245 Legal Office Procedures R 2014Document6 pages245 Legal Office Procedures R 2014api-250674550No ratings yet

- 2c Salaan (Case Digest Plunder)Document2 pages2c Salaan (Case Digest Plunder)Neil SalaanNo ratings yet

- Judicial Appointment in India - CivilDocument28 pagesJudicial Appointment in India - CivilRazor RockNo ratings yet

- People v. BalisacanDocument2 pagesPeople v. BalisacanBeltran KathNo ratings yet

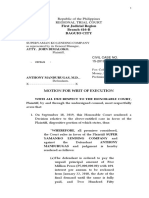

- Motion For Writ of ExecutionDocument5 pagesMotion For Writ of ExecutionDeborah Micah PerezNo ratings yet

- Public Land Act CaseDocument2 pagesPublic Land Act Casediamajolu gaygons100% (1)

- House of Lords - Reynolds v. Times Newspapers Limited and Others PDFDocument2 pagesHouse of Lords - Reynolds v. Times Newspapers Limited and Others PDFshanikaNo ratings yet

- Ocampo V EnriquezDocument59 pagesOcampo V EnriquezFebe TeleronNo ratings yet

- National Housing Authority v. CADocument3 pagesNational Housing Authority v. CAClaire SilvestreNo ratings yet

- R.I Act Under Sec.4 (Copy)Document25 pagesR.I Act Under Sec.4 (Copy)a sreenu100% (1)

- Child Sex Abuse WebinarDocument2 pagesChild Sex Abuse WebinarLinming HoNo ratings yet

- CHED On The Supreme Court Decision On The Removal of Filipino From The New General Education CurriculumDocument1 pageCHED On The Supreme Court Decision On The Removal of Filipino From The New General Education CurriculumJayne Ann GarciaNo ratings yet

- MC 2016 002Document44 pagesMC 2016 002Apollo C. Batausa100% (1)

- Ajay Kumar Mittal and Sneh Prashar, JJDocument8 pagesAjay Kumar Mittal and Sneh Prashar, JJvishesh singhNo ratings yet

- BJJJ JJJDocument11 pagesBJJJ JJJCasey Collera MedianaNo ratings yet