Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Deficit Financing Theory and Practice in Bangladesh

Uploaded by

shuvrodeyCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Deficit Financing Theory and Practice in Bangladesh

Uploaded by

shuvrodeyCopyright:

Available Formats

Deficit Financing Theory and Practice in Bangladesh

Assignment DEFICIT FINANCING: TEORY AND PRACTICE IN BANGLADESH Submitted By Zahirul Islam [pic] DEFICIT FINANCING: TEORY AND PRACTICE IN BANGLADESH INTRODUCTION In the past as today, the deficit budget policy is famous instrument of fiscal policy used to increase the rate of economic growth of the country. That way of financing was establish after the two world wars, oil crises and current financial and economic crises. The objective in seeking deficit financing is to finance the shortfall between government expenditures and tax receipts. Tax increases are not politically palatable. Governments often resort to deficit financing when other components of GDP such as private consumption decline during recessionary periods. Such deficits, if undertaken for a short period with an action plan to create equivalent surplus in near future, could reverse decline in real GDP and stimulate growth in real GDP for the benefit of citizens of the nation. Structural deficits are indicative of inability to reduce entrenched government expenses. The sustainable level of accumulated deficits can also be determined with reference to both the deficit servicing requirements and deficit servicing sources. This analysis will entail identification of cause and effect relationships that determine the factors influencing each of these two areas. As shown by other researchers, the explanatory variables leading to deficits include domestic budgetary receipts; tax structure; budgetary endowments; budgetary discretionary expenses; trade deficit; growth in real GDP; private consumption; domestic capital formation; and foreign direct investment flows. Deficit servicing requirements analysis takes into account accumulated deficit; expected additions to deficit; deficit held by Government Accounts, by Federal Reserve System, by publicdomestic entities, by overseas public & governments, maturity term; and cost of debt. CAUSES OF DEFICIT From a theoretical point of view the causes of sovereign deficits are equally diverse. Primary cause of deficit is that some components of government spending have a built-in growth multiplier that is much higher than the rate of growth of tax receipts. Government expenses can be broken down into discretionary and non-discretionary. Over time, non-discretionary component grows as a percentage of total budgetary expenses, thereby reducing governments ability to reduce expenses without disenfranchising the electorate. Deficits incurred to meet

national emergencies present a special case where the expenditure is incurred without any considerations for fiscal sacrifices. Secondary causes of deficits include shifts in government spending, changes in the competitive environment, globalization, presence of shadow economies, fraud in government programs, role of multinationals, and income distribution that affects private consumption expenditures. During periods of economic downturn, governments often tend to stimulate demand through either direct expenditure on specific projects or through reduction in direct taxes. Stimulation through direct expense is intended to increase employment or save jobs, while stimulation through reduction in direct taxes is aimed at increasing disposable income and, therefore, consumption as well as investments. Reduction in taxes does not necessarily lead to increased consumption and its impact on increasing employment has a longer lag than that of direct expenses. Reduction in taxes on higher income groups and corporations has not always increased investment since higher savings could be hoarded in bank accounts or in retained earnings by corporations. It should be noted that once taxes are reduced, it is difficult to raise them for reducing the budget gap at a later date. The role of competitive forces in allocation of resources and setting prices, especially in free market economies, has been diminishing. Competition has been replaced in reality by oligopoly where a few firms dominate a business sector. Although the number of buyers is large, product is not necessarily homogeneous; information is asymmetric; and the seller has considerable control in setting prices and output level. Oligopolistic firms influence elections and issues to their own benefit by funding elections and lobbying on issues. This often leads to either unintended direct government expenses or increased tax expenditures contributing to deficits. Similarly, increased globalization tends to reduce the effect of domestic multipliers for income and employment due to leakages beyond the borders of a country. Thus growth of a business in a country does not necessarily mean increase in employment in the country as anticipated by historical income and employment multipliers. Presence of shadow economy also accounts for some problems as this unaccounted portion of GDP outside the reach of fiscal measures increases deficit by reducing potential tax revenue. Another factor that might influence deficits is fraud in government run programs that often leads to unintended excess government expenditure. Government bureaucracies can also be included in the list of factors that affect deficits. Bureaucracy often leads to redundant government agencies that essentially perform the same tasks resulting in an increase in government expenses without providing any additional benefits or services. WAYS OF FINANCE DEFICIT AND ITS IMPACT ON ECONOMY There are three ways to finance the deficit taxes, borrowing and monetization (inflation tax). The most popular model of deficit finance is borrowing, which is usually done by issue of government bonds. When the government is over indebted tends through national bank to buy government bonds which increases the money flow and reduces the interest rate pressure. However, it diminishes the real value of money and makes the future unpredictable for the economic actors. Its known that nowadays the current public debt growth is larger then the

growth rate of the economy for most of the industrial countries. Its expected that the growing public debt will cause problems in perspective related to its service. The channels for public debt effect on the economy are the following: 1. Direct effect on the interest rates accompanied with the necessity to sell larger supply of bonds. As the supply of bonds intended for sale increases, their prices tend to fall, and the market interest rates go up; except if credit offer is timelessly elastic and the private borrowing is reduced. The interest rate increase can be temporary limited from the capital inflows; 2. Interest rate component of the public expenditure will tend to rise, and consequently raise future fiscal deficits; 3. Correlated with the previous two effects, the effect on the investment and expenditure and thus on the perspective economic performance; 4. Exchange rate effect and therefore trade flows and capital movement; Academic interest in deficit financing is not new. Researchers have studied this phenomenon for many years. It appears that data is available for loans to sovereign governments from private foreign creditors dating back to the 1820s. A country's tolerance for debt is often the result of many factors including the size of the debt, history of previous defaults, balance of payments weaknesses, its inflation history and weak political institutions. Research studies have focused on sovereign debt from various angles including causes of defaults, the effects of defaults, prescriptions to solve defaults, and early warning systems to predict pending defaults. Although this paper outlines an early warning system, the main emphasis is on understanding the causes of unsustainable national debt that could lead to sovereign defaults. Political risks in the form of instability and/or more polarized experience have known to cause higher defaults. Other researchers have determined that sovereign liquidity crises are mainly driven by economic fundamentals or by sudden shifts in private creditors default expectations. Another area that has drawn some attention is the link between debt crisis and currency destabilization, especially among countries that have severe debt problems at the same time. The currency crisis models have looked at the effects of fixed exchange rates on sovereign debts. Because, fixed exchange rates might lead to an expansionary fiscal policy resulting in an incompatible monetary policy which in turn might give rise to a successful speculative attack against the exchange rate peg (Krugman, 1979; Flood and Garber, 1996). The collapse of the Mexican peso in December 1994; is a good example of such interventions gone wrong. The economic crises faced by a few Latin American countries in the 1990s and the falling bond prices of these countries was influenced by global, regional and country specific factors. In a study conducted by Diaz and Gemmill, the authors estimated that each countrys distance-todefault on a monthly basis for 19942001 could explain up to 80% of the variance of the estimated distance-to-default for each Latin American country (Diaz and Gemmill, 2006). A

countrys banking system is another factor that might contribute to sovereign debt problems. For example, Kaminsky and Reinhart showed that debt crisis is often initiated by both a weakness in the banking sector combined with currency crises (Kaminsky and Reinhart, 1999). Based on review of the literature, it is apparent that the causes of sovereign default are varied and not one factor alone can explain the reasons for defaults. This might be one of the reasons that researchers have had difficulty in developing early warning systems to predict sovereign defaults. One way to avoid sovereign defaults is by developing a system that is able to warn the serial defaulting countries of an impending crisis. Many systems have been proposed and they appear to focus on single variables or specific situations. For example, one possible approach is to identify benchmarks that evaluate the level of optimal foreign debt and a maximal foreign debt (debt-max), when risk is explicitly considered. Using an application of the stochastic optimal controls models Stein and Paladino were able to explain how a country could anticipate default risk. In their research, the authors tried to measure vulnerability to shocks, when there is uncertainty concerning the productivity of capital. Another warning system proposed by Stein uses the dynamic programming/stochastic optimal control (DP/SOC). In his research, Stein used variables such as the optimal foreign debt, consumption, capital and the growth rate of GDP. By comparing the actual debt to the optimal debt he was able to derive a measure of the sustainability of the debt and vulnerability to default problems (Stein, 2005). Research has also shown that focusing on foreign currency borrowings could be a useful early warning system, especially for developing countries. Most developing countries borrow in world capital markets. Typically this borrowing is denominated in one of the major currencies that require periodic servicing. The foreign exchange required to meet the service obligation is often dependent on the export of one or a small number of commodities. This demand usually competes with a number of other claims on export earnings, including both consumption and import of capital goods. Therefore, if a developing country uses commodity-linked borrowing and the interest and/or principal payments on external debt are linked to the price of a country's principal exports, the risk of default is multiplied (Chamberlin, 2006). Although there are many early warning systems proposed, the fact that countries continue to default on sovereign debt assumes that these systems are not employed to forestall defaults. The current debt crisis has produced some conflicting arguments in identifying and dealing with this global issue. Some economists feel that when aggregate demand is far shorter than required for reaching full GDP potential, deficits are justified (Krugman, 2010). As economy resumes growth, demand for goods and services as well as tax receipts will increase to generate offsetting budgetary surpluses. If a country does incur deficits, one way to address the issue is by introducing radical fiscal reform to reduce budgetary expenses and deficits while increasing taxes. This would result in increasing the confidence of both consumers and business leaders - a necessary precondition to improve the overall economy. The assumption is businesses fear deflation and uncertainty more than cyclical deficits (Ferguson, 2009). In contrast, some economists feel that spending cuts, specifically by reducing social transfers and government payroll, is a preferred solution (Hassett, et al., 2009). These economists observe that cold shower treatments, i.e., immediate reduction, in expenditure produces better results as compared to cumulative cuts in government spending over the consolidation years.

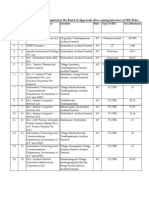

In a study of the OECD countries on fiscal adjustments, Alesina and Perotti concluded that successful adjustments are mainly expenditure based, with a focus on primary current expenditure. On the other hand, Larch and Turrini in their research of the European Union countries found that fiscal consolidation did not reduce debt due to resurgence of expenses Interestingly, based on a study of forty countries, Reinhart and Rogoff suggest that as long as the gross debt to GDP ratio is between 30% and 90%, the negative impact of higher public debt is likely to be modest. Ratio above 90% reduces GDP growth. (Reinhart and Rogoff, 2010). |National Government Budgets for 2010 (in billions of US$) | |Nation |GDP |Revenue |Expenditure |Budget Balance[ |Exp/GDP |Balance/Revenue | Balance/GDP | |US (federal) |14,526 |2,162 |3,456 |-1,293 |23.79% |-59.8% |-8.90% | |US (state) |14,526 |900 |850 |+32 |7.6% |+5.6% |+0.4% | |Japan |4,600 |1,400 |1,748 |+195 |38.00% |-24.9% |+3.56% | |Germany |2,700 |1,200 |1,300 |+199 | 48.15% |-8.3% |+6.08% | |United Kingdom |2,100 |835 |897 |-75 |42.71% |-7.4% |-3.31% | |France |2,000 |1,005 |1,080 |-44 |54.00% |-7.5% |-1.74% | |Italy |1,600 |768 |820 |-72 |51.25% |-6.8% |-3.52% | |China |1,600 |318 |349 |+305 | 21.81% |-9.7% |+5.14% | |Spain |1,000 |384 |386 |-64 |38.60% |-0.5% |-4.60% | |Canada |900 |150 |144 |-49 |16.00% |+4.0% |-3.13% | |South Korea |600 |150 |155 |+29 |25.83% |-3.3% |+2 | On the practical side, evolution of Euro as a common currency in 17 EU countries has brought forth a new set of issues. The financial policy of the Eurozone countries is common but the fiscal policy of each country is different. Thus these countries cannot employ full spectrum of remedies (i.e., devaluation of currency) needed to resolve problems consequential to unsustainable national debt. The bailout of countries on the brink of insolvency by EU and IMF comes with imposition of a few common fiscal policy restrictions that may not take into account country specific economic situation. [pic]

This risk tends to rise when the total need for government borrowing caught substantial part of the total financial transactions. In that case the psychological element will have immense impact on the financial market and further on the financial stability. Figure : General Government Fiscal Balances and Public Debt (Percent of GDP unless noted otherwise) [pic] DEBATE OVER DEFICIT FINANCING Government deficit spending is a central point of controversy in economics, with prominent economists holding differing views. The mainstream economics position is that deficit spending is desirable and necessary as part of countercyclical fiscal policy, but that there should not be a structural deficit: in an economic slump, government should run deficits, to compensate for the shortfall in aggregate demand, but should run corresponding surpluses in boom times so that there is no net deficit over an economic cycle a cyclical deficit only. This is derived from Keynesian economics, and has been the mainstream economics view (in the Anglo-Saxon world especially) since Keynesian economics was developed and largely accepted in the Great Depression in the 1930s. The mainstream position is attacked from both sides advocates of sound finance argue that deficit spending is always bad policy, while some Post-Keynesian economists, particularly Chartalists, argue that deficit spending is necessary, and not only for fiscal stimulus. Advocates of sound finance (in the US known as fiscal conservatism) reject Keynesianism and, in the strongest form, argue that government should always run a balanced budget (and a surplus to pay down any outstanding debt), and that deficit spending is always bad policy. Sound finance has academic support, predominantly associated with the neoclassical-inclined Chicago school of economics, and has significant political and institutional support, with all but one state of the United States (Vermont is the exception) having a balanced budget amendment to its state constitution, and the Stability and Growth Pact of the European Monetary Union punishing government deficits of 3% of GDP or greater. Proponents of sound finance date back to Adam Smith, founder of modern economics. Sound finance was the dominant position until the Great Depression, associated with the gold standard and expressed in the Treasury View that government fiscal policy was ineffective. The usual argument against deficit spending, dating to Adam Smith, is that households should not run deficits one should have money before one spends it, from prudence and that what is correct for a household is correct for a nation and its government. A further argument is that debts must be repaid, and thus it is burdening future generations to run deficits today, for little or no gain.

A similar argument is that deficit spending today will require increased taxation in the future, thus burdening future generations see generational accounting for discussion. Others argue that because debt is both owed by and owed to private individuals, there is no net debt burden of government debt, just wealth transfer (redistribution) from those who owe debt (government, backed by tax payers) to those who hold debt (holders of government bonds).[3] A related line of argument, associated with the Austrian school of economics, is that government deficits are inflationary. Anything other than mild or moderate inflation is generally accepted in economics to be a bad thing. In practice this is argued to be because governments pay off debts by printing fiat money, increasing the money supply and creating inflation, and is taken further by some as an argument against fiat money and in favor of hard money, especially the gold standard. Post-Keynesian economics Conversely, some Post-Keynesian economists argue that deficit spending is necessary, either to create the money supply (Chartalism) or to satisfy demand for savings in excess of what can be satisfied by private investment. Chartalists argue that deficit spending is logically necessary because, in their view, fiat money is created by deficit spending: one cannot collect fiat money in taxes before one has issued it and spent it, and the amount of fiat money in circulation is exactly the government debt money spent but not collected in taxes. In a quip, "fiat money governments are 'spend and tax', not 'tax and spend'," deficit spending comes first. Chartalists argue that nations are fundamentally different from households. Governments in a fiat money system which only have debt in their own currency can issue other liabilities, their fiat money, to pay off their interesting bearing bond debt. They cannot go bankrupt involuntarily because this fiat money is what is used in their economy to settle debts, while household liabilities are not so used. This view is summarized as: But it is hard to understand how the concept of "budget busting" applies to a government which, as a sovereign issuer of its own currency, can always create dollars to spend. There is, in other words, no budget to "bust". A national "budget" is merely an account of national spending priorities, and does not represent an external constraint in the manner of a household budget.[4] Continuing in this vein, Chartalists argue that a structural deficit is necessary for monetary expansion in an expanding economy: if the economy grows, the money supply should as well, which should be accomplished by government deficit spending. Private sector savings are equal to government sector deficits, to the penny. In the absence of sufficient deficit spending, money supply can increase by increasing financial leverage in the economy the amount of bank money grows, while the base money supply remains unchanged or grows at a slower rate, and thus the ratio (leverage = credit/base) increases, which can lead to a credit bubble and a financial crisis. Chartalism is a small minority view in economics; while it has had advocates over the years, and influenced Keynes, who specifically credited it,[5] it is categorically rejected or ignored by virtually all contemporary mainstream economists. A notable proponent was Ukrainian American economist Abba P. Lerner, who founded the school of Neo-Chartalism, and advocated

deficit spending in his theory of functional finance. A contemporary center of Neo-Chartalism is the Kansas City School of economics. Chartalists, like other Keynesians accept the paradox of thrift, which argues that identifying behavior of individual households and the nation as a whole commits the fallacy of composition; while the paradox of thrift (and thus deficit spending for fiscal stimulus) is widely accepted in economics, the Chartalist form is not. An alternative argument for the necessity of deficits was given by celebrated American economist William Vickrey, who argued that deficits were necessary to satisfy demand for savings in excess of what can be satisfied by private investment. Larger deficits, sufficient to recycle savings out of a growing gross domestic product (GDP) in excess of what can be recycled by profit-seeking private investment, are not an economic sin but an economic necessity. Deficit Financing Bangladesh Scenario Debt burden is increasing sharply over time due to increase in the budget deficit. The deficit of budget mainly occurs for the payment of interest, principal of debt burden and the subsidy which are mainly given to non-productive sectors. During the FY 2011-12, the total revenue collection of the government is estimated at Tk. 1,18,385 crore against Tk. 95,187 crore in revised budget of FY 2010-11. The tax collection from NBR is estimated for FY 2011-12 is Tk. 91,870 crore which was Tk. 75,600 crore in FY 2010-11 that is about 21.52 percent higher than that of the previous fiscal year. The revenue expenditure in FY 2011-12 is estimated at Tk. 1,63,589 crore. In FY 2011-12, the total expenditure for development sectors is estimated at Tk. 46,000 crore and Tk. 1,02,903 crore for non-development sectors. [pic] Budget Deficit as percentage of GDP Ratio [pic] Accordingly, in FY 2011-12, the overall budget deficit is estimated at Tk. 45,204 crore which is 5 percent of GDP and is 0.6 percent higher than that of the previous year. In FY 2007-08, it has reached at the peak but after that deficit has turned around to five percent. One of the prime tasks of the fiscal policy of the government is to continue endeavouring for narrowing the gap between expenditure and income in order to offset the budget deficit or to maintain it at a tolerable level. Over the past few years, the overall budget deficit registers an increasing trend that puts serious pressures on the total debt of the country. [pic]

Government Revenue and GDP Ratio If the current trend continues, the government revenue and GDP ratio might be around 12.60 in the upcoming years and in FY 2014-15, it might reach to 12.58.The government revenue and GDP ratio (percentage) is increasing to some extent over the time and stays between 10 to 12 percent. In FY 2000-01, the government revenue and GDP ratio was 10.7 which increased to 12.08 in FY 2005-06. It indicates that the government revenue earning in terms of GDP will slightly be increasing in future vis-a-vis the increasing deficits and debts. Government Revenue and GDP Ratio Debt sustainability is an essential condition for macroeconomic stability and sustainable economic growth. However, debt condition of Bangladesh is not sustainable because this country has more urgent needs than to make external debt service payments. [pic] The debt-GDP ratio in FY 2010-11 has remained at 41 percent. Total debt-GDP ratio in Bangladesh, on average, rose sharply from 33.65 percent during the 1970s to 56.95 percent during the 1980s. Over the last ten years, the debt-GDP ratio has stayed above 40 percent that reflects the high debt burden for Bangladesh. [pic] Budget deficit and its financing in Bangladesh, like in many other developing countries, is very important parameters for analyzing monetary and the fiscal effects on the countrys overall economic development. The government is indebted for debt servicing and deficit financing and the rate is rising swiftly. Taking debt from domestic sources is hindering private investments. Again, for external debt, foreign reserve is declining due to principal and interest payment. The dual effect is mainly responsible for devaluation of currency which in turn increases import bills and further induces debt to meet rising deficit. The national budget for FY 2011-12 has targeted a growth rate of 7 percent which requires about 30 to 35 percent investment share in GDP while in FY 2010-11 the rate has remained at 24.7 percent. The difference between savings and investment may rise in the upcoming years due to increasing debt scenario. If the current trend continues, total national savings and investment share as percentage of GDP might be 30.58 and 25.45 percent respectively in FY 2014-15. Gap between national savings and investment might increase to 5.13 percent which has remained at 3.7 percent in FY 2010-11. In addition, the ratio of external debt and investment in the same fiscal year has been 81.86 percent which clearly depicts the demand for excessive debt than investment. Deficit financing, money supply and inflation are interlinked. The government has to ensure adequate money supply which in turn increases further inflation. On the other hand, government debt from banking sector is hindering private investment. The outcome is lesser actual production than potential production and more inflation. Consequently, the rate of inflation (12

month average) has increased from 7.31 percent in FY 2009-10 to 8.8 percent in FY 2010-11. In addition, money supply (M1 and M2) has increased to 17.18 and 21.34 percent respectively in June 2011 than that of June 2010. Government Expenditure and GDP ratio In FY 2012-13, the government expenditure and GDP ratio might be 15.38 and it might reach to15.46 in FY 2014-15, if the current trend prevails. However, in FY 2000-01, the government expenditure and GDP ratio was 15.5 while in FY 2007-08 it has risen to 16.5. [pic] Government expenditure and GDP ratio stays between 14 to 17 percent of its GDP earnings over the years. Government expenditure and GDP ratio (in percent) is much higher than that of the government revenue and GDP ratio that keeps on increasing the deficit in successive years. Combining the government revenue and GDP ratio and government expenditure and GDP ratio, it is seen that over the time the trend of deficits might increase and it might stay around four to five percent of GDP earnings. SOURCES OF DEFICIT FINANCING Economic theory tells that if debt financing is inflationary when met by borrowing from central bank whereas there is a possibility of crowding out of private sector investment if the borrowing conducted from the commercial ones. Again, if it is met by issuing bonds, the cost of debt financing will be higher. Hence debt financing and the method of its management are important issues. In general, deficit financing is met by expanding monetary base. Debt financing by issuing bond is less popular than the money creation. There are two sources of deficit financing: internal and external debt. The government has become more dependent on banking sectors other than non-banking ones for domestic financing over the time. In FY 2010-11, government has borrowed 4.43 times higher from banking sectors in comparison to that of FY 2001-02 indicating a sharp crowding out effect which has dampened private investments. The government borrowing from banking sector in FY 2010-11 was 1.43 percent of GDP while it was 0.45 percent from non-banking sectors. Each year a major portion of its budget expenditure gets expanded on interest payment. It is seen that in FY 2006-07, 11 percent of the total development and non-development expenditure. [pic] 1. Internal Debt The government mainly borrows both from the Bangladesh Bank and the commercial ones. In FY 2010-11, the government has borrowed 4.43 times higher from banking sectors (BDT 11,240.5 crore) in comparison to that of FY 2001-02 indicating a sharp crowding out effect which has dampen private investments. In FY 2001-02, government has borrowed an amount of

Tk. 2,534.9 crore from banking sector whereas Tk. 4,711.47 crore has been borrowed from nonbanking sectors. The government has become more dependent on banking sectors other than non-banking ones for domestic financing over the time. [pic] The borrowing from banks as percentage of GDP has been increasing over the time. In FY 201011, the government borrowing from banking sector is 1.43 percent of GDP while it is 0.45 percent from non-banking sectors. However, in FY 2001-02, the government borrowing from banking sector amounts 0.93 percent of GDP while from non-banking sector it totals 1.72 percent. In FY 2001-02, total domestic debt as percentage of GDP was 2.65 percent while in FY2010-11, it became 1.88 percent. Total domestic borrowing as percentage of GDP remains 1.5 to 3.0 percent of GDP over the last ten years. Continuation of current trend will result into an increasing movement in domestic debt. In FY 2013-14, the government may have to borrow Tk. 16,254.42 crore from domestic sources while it might increase to Tk. 17,755.76 crore in FY 2014-15. External Debt Total external debt in FY 2010-11 amounts to USD 21,347.44 million while in FY 1972-73 it was only USD 65 million. Over the time the amount of external debt has been increasing at a Bangladesh Economic Update, August 2011. In FY 2014-15, the amount of external debt might amount USD 23,475.68 million. The principal and interest payment in FY 2010-11 are 724.9 million and USD 186.42 million respectively, a total payment of USD 911.32 million. higher rate and therefore in FY 1989-90, the amount has reached to USD 1,069 million, incurring a growth of additional USD 55 million each year. [pic] If the current trend continues, there might be an increasing trend of external debt in forthcoming years. In FY 2012-13 and FY 2014-15, the amount of external debt might amount USD 22,411.56 million and USD 23,475.68 million respectively. Conclusion Since the past, the governments used the fiscal policy in order to achieve the planned projects in their political programs. In that process, they are keen to implement deficit fiscal policy to increase the economic growth rate. These fiscal measures are most justifiable in terms of economic crisis as the current one and wars. Although, most governments intend to use deficit policy for unreasonable objectives like unproductive government expenditures. What is inevitable in this kind of budget finance is the future tax burden that will fall upon the next generations. Thats not argumentable but should be taken into consideration when the government loses orientation in the budget policy. But if the fiscal policy is prudent and

coordinated with the monetary policy, this move will produce economic growth and improve the economic condition of the country. In deficit finance the multiplier effect is bigger then the initial change in government expenditure but obviously its partly declined cause the crowding out effect which reduces the private demand for loanable funds because the private investments are considered as more efficient then the government. Also at the end is reviewed the potential correlation between the budget and trade deficit in spite all other factors that can have an impact of capital movement. The conclusion from the previous description is that the fiscal stimulations play important role in the economic growth of the country, especially if the monetary policy of that country is restrictive and doesnt help with creating better economic conditions for the firms in order to improve their productivity. Thats why the intervention from the fiscal policy can be crucial for the economy, normally if it is used in productive way. REFERENCE ATANASOVSKI, ZIVKO (2004). Public Finance. Economic faculty. Skopje DE LAROSIERE J. (1986). The growth of public debt and the need for fiscal discipline. Public finance and public debt. Wayne State University Press. FRIEDMAN, B. (1978). Crowding Out or Crowding In? Economic Conseqences of Financing Government Debt. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity No. 3, pp. 593-641 GABER S. (2009). Fiscal Stimulations for Improving the Business Environment in Republic of Macedonia. PIEB No.3. KRUGMAN, P. (2009). Crowding In. New York Times. LANGDANA, F. (2009). Macroeconomic Policy: Demystifying Monetary and Fiscal Policy. Springer. MANKIW, G. (2009). Brief Principle of Macroeconomics, 5 ed. South-Western Cengage Learning. SANTOW, L. (1988). The Budget Deficit: The Causes, the Costs, the Outlook. New York Institut of Finance. SARGENT AND WALLACE (1985). Some Unpleasent Arithmetic. Federal Reserve Bank of Mineapolis. SPILIMBERGO, A., SYMANSKI S., BLANCHARD O. AND COTTARELLI C.(2008). Fiscal Policy for the Crisis. IMF Staff position Note.

You might also like

- Exchange Control RegulationDocument5 pagesExchange Control RegulationArjun lal KumawatNo ratings yet

- Parkinmacro15 1300Document17 pagesParkinmacro15 1300Avijit Pratap RoyNo ratings yet

- Botswana Power SectorDocument19 pagesBotswana Power SectorJeremiah MatongotiNo ratings yet

- The Great DepressionDocument2 pagesThe Great DepressionRohan Srivastava0% (1)

- Eco Dev - OrendayDocument17 pagesEco Dev - OrendayZhaira OrendayNo ratings yet

- Import Substitution And/or Export Led Growth Necessary For The Economic Development of BangladeshDocument11 pagesImport Substitution And/or Export Led Growth Necessary For The Economic Development of Bangladesholiur rahman100% (2)

- Public Finance (MA in Economics)Document139 pagesPublic Finance (MA in Economics)Karim Virani91% (11)

- Relationship Between Inflation and Unemployment in IndiaDocument5 pagesRelationship Between Inflation and Unemployment in Indiaroopeshk6479No ratings yet

- The Fiscal Deficit: Themes Economic BriefsDocument2 pagesThe Fiscal Deficit: Themes Economic BriefsVirendra PratapNo ratings yet

- Trade Barriers FinalDocument30 pagesTrade Barriers FinalMahesh DesaiNo ratings yet

- 3.indicators and Measurement of Economic DevelopmentDocument17 pages3.indicators and Measurement of Economic Developmentramkumar100% (1)

- Harrod Model of GrowthDocument6 pagesHarrod Model of Growthvikram inamdarNo ratings yet

- An Evaluation of The Trade Relations of Bangladesh With ASEANDocument11 pagesAn Evaluation of The Trade Relations of Bangladesh With ASEANAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Exchange Control in IndiaDocument3 pagesExchange Control in Indianeemz1990100% (5)

- The Impact of Debt On Economic Growth A Case Study of IndonesiaDocument23 pagesThe Impact of Debt On Economic Growth A Case Study of IndonesiaKe Yan OnNo ratings yet

- Balance of PaymentsDocument16 pagesBalance of PaymentsShipra SinghNo ratings yet

- Money Market Concept, MeaningDocument4 pagesMoney Market Concept, MeaningAbhishek ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Economics Project 2Document13 pagesEconomics Project 2Ashish Singh RajputNo ratings yet

- Definition of StagflationDocument5 pagesDefinition of StagflationraghuNo ratings yet

- Global Economic Crisis and Indian EconomyDocument11 pagesGlobal Economic Crisis and Indian EconomyabhaybittuNo ratings yet

- SWOT Analysis of Bangladesh EconomyDocument14 pagesSWOT Analysis of Bangladesh EconomyIqbal HasanNo ratings yet

- Meaning of Exchange ControlDocument2 pagesMeaning of Exchange ControlDinesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Parkinmacro4 1300Document16 pagesParkinmacro4 1300Mr. JahirNo ratings yet

- Lec3 Harrod-Domar GrowthDocument17 pagesLec3 Harrod-Domar GrowthMehul GargNo ratings yet

- Burden of Public DebtDocument4 pagesBurden of Public DebtAmrit KaurNo ratings yet

- Big Push Theory of Economic DevDocument2 pagesBig Push Theory of Economic DevsukandeNo ratings yet

- Sickness in Small EnterprisesDocument15 pagesSickness in Small EnterprisesRajesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Economic Development/growth of Zambia Since IndeendenceDocument10 pagesEconomic Development/growth of Zambia Since IndeendenceSing'ombe SakalaNo ratings yet

- Indian Fiscal PolicyDocument2 pagesIndian Fiscal PolicyBhavya Choudhary100% (1)

- MacroEconomic NotesDocument34 pagesMacroEconomic NotesNaziyaa PirzadaNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Activities of NGO in BangladeshDocument8 pagesAssignment On Activities of NGO in Bangladeshঅচেনা একজন0% (1)

- Taxation JunaDocument551 pagesTaxation JunaJuna DafaNo ratings yet

- Keynesian TheoryDocument22 pagesKeynesian TheorykavitaNo ratings yet

- Budget & EconomyDocument13 pagesBudget & Economysonu_dpsNo ratings yet

- Capital Structure TheoriesDocument31 pagesCapital Structure Theoriestannu2114No ratings yet

- Effects of Financial Inclusion On The Economic Growth of Nigeria 1982 2012Document18 pagesEffects of Financial Inclusion On The Economic Growth of Nigeria 1982 2012Devika100% (1)

- Instruments of Trade Promotion in IndiaDocument12 pagesInstruments of Trade Promotion in Indiaphysics.gauravsir gauravsir100% (1)

- UnemploymentDocument20 pagesUnemploymentRajalaxmi pNo ratings yet

- Goods and Money Market InteractionsDocument25 pagesGoods and Money Market Interactionsparivesh_kmr0% (1)

- Internship Report On General Banking of SEBLDocument64 pagesInternship Report On General Banking of SEBLSohanul Haque Shanto100% (1)

- What Is Social AccountingDocument13 pagesWhat Is Social AccountingAhmed Al MasudNo ratings yet

- Limitations of National Income AccountingDocument1 pageLimitations of National Income AccountingAshutosh SatapathyNo ratings yet

- GlobalisationDocument6 pagesGlobalisationjimmy0537100% (3)

- Impact of LPG PDFDocument12 pagesImpact of LPG PDFRavi Kiran JanaNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Balance of Trade (BOT) & Balance of Payment (BOP)Document2 pagesDifference Between Balance of Trade (BOT) & Balance of Payment (BOP)Bhaskar KabadwalNo ratings yet

- Commercial Policy: Tariff and Non-Tariff BarriersDocument35 pagesCommercial Policy: Tariff and Non-Tariff BarriersKeshav100% (3)

- EconomicsDocument32 pagesEconomicsSahil BansalNo ratings yet

- Fiscal and Monetary Policy of IndiaDocument62 pagesFiscal and Monetary Policy of IndiaNIKHIL GIRME100% (1)

- Money and Banking PDFDocument19 pagesMoney and Banking PDFMOTIVATION ARENANo ratings yet

- Role of Green Economy in The Context of Indian EconomyDocument5 pagesRole of Green Economy in The Context of Indian EconomyEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- An Empirical Study in Bangladesh Forensic AccountingDocument9 pagesAn Empirical Study in Bangladesh Forensic AccountingTanvir HossainNo ratings yet

- Balance of Trade and Balance of Payment NewDocument27 pagesBalance of Trade and Balance of Payment NewApril OcampoNo ratings yet

- Fiscal Policy of IndiaDocument20 pagesFiscal Policy of Indiasaurav82% (11)

- Group Assignment On Bangladesh BankDocument20 pagesGroup Assignment On Bangladesh BankAlphahin 17No ratings yet

- Crowding OutDocument3 pagesCrowding OutsattysattuNo ratings yet

- National IncomeDocument13 pagesNational IncomeEashwar ReddyNo ratings yet

- BOPDocument36 pagesBOPAhmed MagdyNo ratings yet

- Limitations of Harrod DomarDocument3 pagesLimitations of Harrod DomarprabindraNo ratings yet

- Chap 13Document5 pagesChap 13Jade Marie FerrolinoNo ratings yet

- ECO 22 Midterms Supplemental Reading MaterialDocument2 pagesECO 22 Midterms Supplemental Reading MaterialjonallyelardeNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Int'l MacroeconomyDocument4 pagesUnderstanding The Int'l MacroeconomyNicolas ChengNo ratings yet

- FashionDocument34 pagesFashionshuvrodeyNo ratings yet

- 1.heat and FlameDocument16 pages1.heat and FlameshuvrodeyNo ratings yet

- Table of Fibre DensitiesDocument1 pageTable of Fibre DensitiesamishcarNo ratings yet

- Neval and Armed Force ClothingDocument7 pagesNeval and Armed Force ClothingshuvrodeyNo ratings yet

- 2.fire FightersDocument17 pages2.fire FightersshuvrodeyNo ratings yet

- Financial Ratio Analysis of Bank Performance PDFDocument24 pagesFinancial Ratio Analysis of Bank Performance PDFRatnesh Singh100% (1)

- Rock Music Is A Genre of Popular Music That Originated AsDocument10 pagesRock Music Is A Genre of Popular Music That Originated AsshuvrodeyNo ratings yet

- Credit RiskDocument12 pagesCredit RiskshuvrodeyNo ratings yet

- Budget Deficits, National Saving, and Interest RatesDocument83 pagesBudget Deficits, National Saving, and Interest RatesshuvrodeyNo ratings yet

- Pawan KalyanDocument11 pagesPawan KalyanshuvrodeyNo ratings yet

- Sick IndustriesDocument19 pagesSick IndustriesshuvrodeyNo ratings yet

- Economic Implications From Deficit FinanceDocument19 pagesEconomic Implications From Deficit FinanceAna-Maria JincaNo ratings yet

- LawDocument7 pagesLawshuvrodeyNo ratings yet

- LawDocument7 pagesLawshuvrodeyNo ratings yet

- Greenhouse EffectDocument1 pageGreenhouse EffectshuvrodeyNo ratings yet

- Student Attitude ReportDocument188 pagesStudent Attitude ReportCarmii CastorNo ratings yet

- MarketingDocument6 pagesMarketingshuvrodeyNo ratings yet

- 28 B F I, 2012, EyaeviDocument3 pages28 B F I, 2012, EyaevishuvrodeyNo ratings yet

- MPRA Paper 21022Document9 pagesMPRA Paper 21022shuvrodeyNo ratings yet

- Ashraf UlDocument2 pagesAshraf UlshuvrodeyNo ratings yet

- Diversity & InclusionDocument1 pageDiversity & InclusionshuvrodeyNo ratings yet

- Application ID FormDocument1 pageApplication ID FormshuvrodeyNo ratings yet

- Futures and Options On Foreign Exchange: International Financial ManagementDocument50 pagesFutures and Options On Foreign Exchange: International Financial ManagementvijiNo ratings yet

- Rekening Koran Bank Mandiri Bulan Mei 20022Document11 pagesRekening Koran Bank Mandiri Bulan Mei 20022gedearNo ratings yet

- Ibt Midterms OutlineDocument11 pagesIbt Midterms Outlinetimothee chalametNo ratings yet

- February 2022 Master Plumber Licensure ExaminationDocument9 pagesFebruary 2022 Master Plumber Licensure ExaminationRapplerNo ratings yet

- Economics Optional Paper 1Document24 pagesEconomics Optional Paper 1Ravi DubeyNo ratings yet

- LIC Premium Receipt StatementDocument2 pagesLIC Premium Receipt StatementRMNo ratings yet

- Steve Romick SpeechDocument28 pagesSteve Romick SpeechCanadianValueNo ratings yet

- List of Formal Approval SEZDocument34 pagesList of Formal Approval SEZsampuran.das@gmail.comNo ratings yet

- Vedanta HW Price List 02.09.23Document2 pagesVedanta HW Price List 02.09.23NikhilNo ratings yet

- L4M6 - Chapter 1.1 - 1.4Document32 pagesL4M6 - Chapter 1.1 - 1.4Alvin Reddy100% (1)

- Prepare Financial Report IbexDocument13 pagesPrepare Financial Report Ibexfentahun enyewNo ratings yet

- Economics Project 3rd SemesterDocument17 pagesEconomics Project 3rd SemestersahilNo ratings yet

- Incoming International Wire Instructions-TDA 0320Document2 pagesIncoming International Wire Instructions-TDA 0320Juan Miguel OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Industrialisation Collectivisation in UssrDocument11 pagesUnderstanding Industrialisation Collectivisation in UssrMR. EXPLORERNo ratings yet

- RIT IndividualDocument77 pagesRIT IndividualAngelica Pagaduan100% (1)

- Final Assessment - Introduction To Economics - 05082021Document1 pageFinal Assessment - Introduction To Economics - 05082021TabishNo ratings yet

- Calculate The Price Elasticity of Demand of Kinz HotelDocument3 pagesCalculate The Price Elasticity of Demand of Kinz HotelAllana NeupaneNo ratings yet

- A Project Report ON Derivatives: Submitted ToDocument34 pagesA Project Report ON Derivatives: Submitted ToAnu PillaiNo ratings yet

- Burton (2015) Organizational Design BDocument22 pagesBurton (2015) Organizational Design BCarol Viviana Zanetti DuranNo ratings yet

- Ola UberDocument4 pagesOla UberAnil SinghNo ratings yet

- List of Filipino Architects and Their Works Architect Works: SebreroDocument12 pagesList of Filipino Architects and Their Works Architect Works: SebreroEllebanna OritNo ratings yet

- Buy Back AssingmentDocument5 pagesBuy Back AssingmentDARK KING GamersNo ratings yet

- Indian Villages – Our Strength or WeaknessDocument2 pagesIndian Villages – Our Strength or WeaknessJAY SolankiNo ratings yet

- Exercises 2 - SolutionsDocument3 pagesExercises 2 - SolutionsbatuhanNo ratings yet

- International Finance BBA - 403: Lectures 2 September 30, 2020Document23 pagesInternational Finance BBA - 403: Lectures 2 September 30, 2020ifrah ahmadNo ratings yet

- Meterbill 6909Document3 pagesMeterbill 6909vsinghrajput1983No ratings yet

- SS2 Contemporary World - The Globalization of World Economics - NotesDocument3 pagesSS2 Contemporary World - The Globalization of World Economics - NotesJulie Ann MontalbanNo ratings yet

- II. Compilation of GDP by Income ApproachDocument15 pagesII. Compilation of GDP by Income ApproachPreetiNo ratings yet

- MercantilismDocument2 pagesMercantilismBapu FinuNo ratings yet