Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Aburumuhffh

Uploaded by

Sameer_Khan_60Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Aburumuhffh

Uploaded by

Sameer_Khan_60Copyright:

Available Formats

Running Head: EDUCATORS AWARENESS AND PERCEPTIONS OF ARAB-AMERICANS

EDUCATORS CULTURAL AWARENESS AND PERCEPTIONS OF ARAB-AMERICAN STUDENTS: BREAKING THE CYCLE OF IGNORANCE

Hamsa A. Aburumuh, M.A. Howard L. Smith, Ph.D. Lindsay G. Ratcliffe, M.A.

The University of Texas at San Antonio

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

Abstract This study used mixed methods to examine educators cultural awareness and perceptions of ArabAmerican students. An analysis revealed that most educators lacked basic knowledge about the Arab and Islamic cultures. This lack of cultural knowledge may thwart the attempts of educators to develop caring relationships with Arab-American students and their families. The authors conclude that Arab-American students will be at a greater risk of symbolic violence unless educators focus their efforts in four broad dimensions: (1) understanding the Arab and Islamic cultures; (2) eliminating negative stereotypes and erroneous beliefs about these cultures; (3) providing culturally responsive teaching; and (4) maintaining caring relationships with Arab-American students and their families.

Key Words: Arab-American students, Care Theory, cultural awareness, teacher preparation, culturally responsive teaching, stereotyping

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

Introduction While public schools in the United States have made great strides toward developing nurturing academic environments for all students, much remains to be done. One critical issue which has received little attention is that educators lack basic understanding of Arab-American students and their cultures. John R. Weeks (as quoted in Shaikh, 2002), director of the International Population Center at San Diego State University, asserted that there can be no question that the Muslim population in this country is large and is growing at a fairly rapid paceIt is projected that by the turn of the century, Islam will be the second largest religion in the United States (p. 4). Al-Hazza and Lucking (2005) have noted that fiftyfour percent of Arab-Americans, or 400,000 citizens, are of public-school age. The diversity of the Arab and Islamic cultures and the ignorance about them may challenge educators perceptions of students of these backgrounds. Although Arab-Americans represent a relatively small minority in U.S. public schools, school districts are obligated to provide them with culturally responsive caring and instruction. This article, based on a larger study conducted by the first author in 2007, focuses on two questions: 1. Do educators identify the differences among the terms Arabic, Arab, Islam, and Muslim? 2. Do educators possess basic knowledge about Arab-Americans and their cultures? This paper explains some of the challenges facing both Arab-American students and their teachers, explain some myths and misunderstandings in the teaching force about Arab-Americans, introduce Care Theory as a framework for approaching this issue, present the results of the research study, and finally, discuss the studys implications for educational practice in U.S. public schools.

Background of the Study Challenges Facing Arab-American Students The Arabic-speaking student population in U.S. public schools has increased dramatically in recent years. The number of Americans claiming Arabic-speaking ancestry grew by more than forty-five

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

percent between 1990 and 2000 (AAI, 2008). Providing linguistically appropriate instruction (e.g., bilingual and foreign language programs) is essential to meet the needs of these students. Federal law mandates that school districts establish a bilingual education program when 20 or more English Language Learners (ELL) speak the same foreign language at the same grade level ("Adaptations," 2007). School districts, however, are not establishing these programs quickly enough to meet the ELL students needs. For example, in 2005-2006, district records at the Southwest Public Independent School District (SWPISDa pseudonym), revealed that 117 of the districts 5100 ELL students spoke Arabic. At 2.3% of the ELL population, they represented the districts second largest group of foreign-language speakers. Although these students legally qualified for bilingual education, the district did not have a program in place to serve them (Aburumuh, 2007). In 2005, SWPISD requested a waiver from the Texas Education Agency (TEA), allowing the district one year to set up an Arabic-English bilingual education program to meet the needs of its Arabicspeaking population. At the time Texas had no Arabic bilingual certification, few teachers possessed sufficient fluency in standard Arabic to teach the curriculum, and few Arabic-speaking individuals were certified teachers. According to Al-Batal (2006), few U.S. educational institutions provide qualified and certified Arabic language teachers. He wrote: At present, the field does not have enough experienced and trained teachers to meet the student demand, nor is it producing these teachers. Many teachers of Arabic today are native speakers who hold degrees in disciplines ranging from political science to journalism to engineering but have little or no language pedagogy training. (p.42)

Based on the first authors involvement in the development of SWPISDS Arabic-English bilingual program, she determined that completion of this program will be complex and fraught with logistical challenges (e.g., translation of standards, timely communication to parents, and transportation to

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

schools with Arabic-English bilingual programs). Even when U.S. school districts overcome these basic challenges, however, they have more complex barriers to surmount (Aburumuh, 2007). First, districts must determine the cultural accuracy of the educational materials they consider for purchase. The Arab and Islamic worlds are dynamic and, as such, experience constant changes. Available materials may be culturally biased, outdated or simply inaccurate (Al-Hazza & Lucking, 2005). Second, since few research studies have been done on Arab-American students, districts have scant literature to draw upon as they build curricula (Al-Hazza & Lucking, 2005; Nieto, 2004; Suleiman, 1996). Third, and perhaps most critical, all U.S. citizens are subjected to a relentless stream of negative images of Arabs and Muslims in mainstream media, leading to the formation of inaccurate and pernicious stereotypes (Al-Hazza & Lucking, 2005; Rainey, Morelli, & Hakki, 1999). Another significant challenge to educators is the strong tendency to confound the culturallinguistic term Arab with the religious term Islam. A common misperception is that all Arabs are Muslims, that all Muslims are Arabs, and that the two terms are interchangeable (Al-Hazza & Lucking, 2005). Another misperception is that all Arabic-speaking students are Muslims or vice versa; for instance, teachers may have Arabic-speaking Christian or Jewish children in their classrooms. Additionally, one must consider Arabic language diglossia: while classical or standard Arabic exists, more than 20 different dialect languages are used in everyday spoken communication, which differ substantially from the standard. For this reason the U.S. Department of State categorizes Arabic as a superhard language, one that is exceptionally difficult for native English speakers to learn (Ryding, 2006, p. 15). Challenges notwithstanding, school districts are accountable for the academic achievement of Arab and Muslim students. Even though research encourages the development of Arabic-English bilingual programs to address the linguistic and cultural needs of the students (e.g., Aburumuh, 2007), there remains a crucial prerequisite for such programs. Specifically, educators must be willing to develop culturally responsive caring, [because] even the most well-designed bilingual education programs may not be meaningful and effective without the right disposition or attitude of the teacher (Aburumuh, 2007,

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

p.7). This article assesses the knowledge a group of educators have about Arab and Muslim American cultures and examine the ways in which their understandings may influence their teaching practices. We also propose a framework to increase the likelihood of teacher effectiveness and student achievement.

Review of Literature The Invisibility of Arab-Americans in the United States Arab-American students do not comprise a homogeneous group but in fact represent diverse backgrounds (Nabor, 2000). This diversity stems from geographic, ethnic, religious, political, and socioeconomic factors and the students educational expectations and attitudes reflect these differences (Suleiman, 1996). Unfortunately, little research exists on Arab-American students and their performance in public schools (Al-Hazza & Lucking, 2005; Nieto, 2004; Suleiman, 1996). In fact, until September 11, 2001, Arab-Americans had been considered an invisible minority (Nabor, 2000; Nieto, 2004; Suleiman, 1996). This invisibility may have multiple causes. First, Arab-American immigration to the United States was voluntary (Ogbu & Simons, 1998), so they largely avoided problems associated with involuntary immigrants and subjugated groups (Hovey & Magana, 2000; Pumariega, Rothe, & Pumariega, 2005). Second, although many tend to avoid complete assimilation, most Arab-Americans have made relatively smooth transitions to U.S. society by developing biculturalism (Benet-Martinez, Leu, Lee, & Morris, 2002; Sapna, 2004; Soto, 2002) or the ability to code-switch between cultures (Heinrich, 1991; Molinsky, 1999; 2007). Third, because they experience limited problems of assimilation Arab-Americans have received little media attention (prior to September 11, 2001) and negligible attention in educational and social science research (Al-Hazza & Lucking, 2005). Fourth, unlike some minority groups, Arabs are not easily categorized by physical characteristics (Naber, 2000; Nieto, 2006; Suleiman, 1996). Finally, Arab-Americans historically have not faced educational failure, the customary prompt for educational research (Nieto, 2006; Suleiman, 1996). In fact, the U.S. Census (2000) indicates that Arab

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

Americans as a group are more educated than Americans on the whole: 36.3% of Arab Americans hold bachelors degrees, and 15.2% hold graduate degrees; the American averages are 20.3% and 7.2%, respectively. More than 40% of Arab-Americans have at least a bachelors degree, compared to 24% of Americans overall (Al-Hazza & Lucking, 2005; AAI, 2008). The majority of Arabs immigrate for the purposes of university study, a fact which may account for their academic success (Nieto, 2004). Moreover, well-educated Arab-American parents tend to encourage education for its own sake, not solely for purposes of employment (Nieto, 2004; Suleiman, 1996). Arab-American students also tend to conform to the expectations of their teachers, embracing behaviors that contribute to school success (Dwairy, 2004; Suleiman, 1996). Although their invisibility has helped Arab-Americans assimilate into mainstream culture, it has also caused them to be overlooked as a group in schools. As one educator in Fairfax County, Virginia noted, The kids from the Middle East are the lost sheep in the school system. They fall through the cracks in our categories (Wingfield & Karaman, 1995, p. 8). Because they demonstrate few academic handicaps, districts seldom review the general curriculum for instances in which Arab cultures can be acknowledged or explored in positive ways.

Overcoming Stereotypes of Arab-Americans Perhaps the most significant challenge facing educators working with Arab-American students is moving beyond the damaging stereotypes deeply ingrained in American consciousness (Said, 1997). These stereotypes are not new; in 1982, James J. Zogby, founder and president of the Arab-American Institute (AAI) and senior analyst with the polling firm Zogby International (AAI, 2006), recalled a painful experience he endured as an Arab-American father. In When Stereotypes Threaten Pride, Zogby (1982, p. 12) wrote: Each Halloween, at my childrens school, the students stage a parade, proudly displaying their costumes to friends and teachers. Two years ago on this festive occasion eight of the students

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

dressed as Arabs. Their accessories included big noses, guns, knives, oil cans, and moneybags. When a short time later, the school held an ethnic festival, my son Joey and daughter Liz hesitated to wear their ethnic garb. Confusion and perhaps fear made them resist any display of pride. What for other students was the joy of ethnicity had become for my Arab-American children the pain of ethnicity. Adjustment to the tensions of pluralism is a difficult process-particularly for children. The mockery that Arab-American children undergo is no longer in jest, and its source is no longer primarily their peer groups.

Twenty-five years after Zogbys article was published, these damaging stereotypes persist. Rainey, et al. (1999) noted that when writers or Hollywood producers want to portray a threatening individual or terrorist, they put him in Middle Eastern attire, give him an accent, and make him look Arab. This attitude also carries over to Islam and Muslims. Of all world religions, Islam may be, as Ariza (2006) wrote, one of most maligned and least understood (p. 60). In a similar study of images and stereotyping cultural groups, Wingfield and Karaman (2001) found that the most damaging images are those of Arabs and Muslims as terrorists (p.132). It is myopic to reduce the Arab and Islamic cultures to a few negative images while ignoring their thousands of years of historical and civic accomplishments. The sad irony of these pervasive stereotypes and their pernicious outcomes is that they negate the quintessential principal of Islamone shared by all religionsthe principal of peace. Data from the present study reveal that most educators (73.2%) acknowledged that Arabs and Muslims have made significant contributions to U.S. culture. Yet a recent national survey indicated that of all religious groups, Muslims had the lowest favorable rating and highest unfavorable rating (Wormser, 2002).

This study examined educators knowledge and perceptions of Arabic and Islamic cultures. One important element of this knowledge is basic terminology, which, as the data suggest, is commonly misused or misapplied.

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

Arabic, Arab, Islam, and Muslim: Important Distinctions The terms Arabic, Arab, Islam and Muslim are frequently conflated, leading to one of the major barriers to maintaining caring relationships with Arab-American students in U.S. public schools. For this reason, we wanted to assess educators knowledge of these terms using the corresponding section of the E-CAP survey. Arabic, the native language of 300 million people, is the official language of more than twenty countries and is one of the oldest of the Semitic groups of languages (Nydell, 2006). The term Arab refers to an individual who speaks the Arabic language and who has Semitic roots leading back to the Arabian Peninsula (Suleiman, 1996). Contrary to popular belief, Iranians, Turks, Armenians, Kurds, Afghans, and Pakistanis are not Arabs (i.e. Arabic speakers), although the majority are Muslim and reside in the same part of the world. Islam refers to a monotheistic religion revealed to prophet Muhammad Ibn (son of) Abdu Allah between the years 610 and 632 of the Common Era. (According to Islamic practice, whenever a prophet is mentioned in writing, his name is followed by the blessing , meaning may the blessings

and peace of Allah be upon him). Due primarily to immigration, Islam has become the second largest religion in both the United States and Europe (Nydell, 2006). The term Muslim, like Islam, comes from the three-letter Arabic root s-l-m and literally means one who willfully submits (to God) (Shaikh, 2002, p. 2). Muslim refers to one who (1) believes in the Shahada, the declaration of faith containing the basic creed of Islam, (2) embraces a lifestyle in accordance with Islamic principles and values, and (3) calls for complete acceptance of the teachings and guidance of God as manifested in the holy Quran and the life example of the Prophet Muhammad (Shaikh, 2002). Teachers may have students who fit a wide variety of categories: Muslim students who are not Arabs (e.g., Pakistani, Afghani, Turkish), Arab students who are not Muslims (e.g., Christians or Jews) and even Muslim students who are fifth- and sixth-generation Americans (i.e., Islamic converts). A

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

10

caring educator will avoid making assumptions and hasten to ask questions to learn about the cultural, linguistic, and religious backgrounds of the students they wish to teach. The first author recalls a confusing moment when meeting a young Arabic-speaking child in a US public school. After marveling at their exchange in Arabic, the students teacher asked her if she would make a presentation on Ramadanthe most sacred period of the year for Muslim. The young girl looked embarrassed and bewildered. The teacher was perplexed. As the first author knew immediately from just a few words (nobody in my family fasts for Ramadan), the young Arabic speaker was Christiannot Muslimand had scant knowledge of the month-long period of fasting observed by people of a different faith. As this example demonstrates, good intentions are insufficient for effective, caring teaching. Teachers can develop an inclusive, motivating curriculum and design effective instruction to ensure that all students perform at a high level, that their needs are met, and that their identities are validated in the classroom. To accomplish these goals, they must move beyond their current level of understanding and outside their comfort zone. It is at this point that we encounter Care Theory.

Theoretical Framework: Care Theory In todays technological age we can access countless sources of information about cultures other than our own. Basic cultural knowledge alone, however, is insufficient to create learning environments that support the academic achievement of linguistically and culturally diverse populations. The ultimate goal is to demonstrate acceptance of the whole child, including familiarity and respect for the childs culture, language, and worldview. Noddings has maintained that education is based on moral and ethical purposes (Grant & LadsonBillings, 1997). When teachers work from an ethic of care, they make a conscious moral commitment to care for students and to develop reciprocal relationships with them and their families (Grant & LadsonBillings, 1997). Caring is a way of being in relation, not a set of specific behaviors (Noddings, 2005, p.

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

11

17). It is one of the cornerstones of the caring-centered multicultural education framework; it directs teachers to understand that relationships are central to teaching (Pang, 2005, p. 12). From this perspective, teaching is a reciprocal, relational process which demonstrates proper regard for human affections, weaknesses, and anxieties (Valenzuela, 1999, p. 23). Research shows that students need personal connections with teachers and that such connections are made when teachers acknowledge [students] presence, honor [students] intellect, respect [students] as human beings, and make them feel that they are important (Gay, 2000, p. 49). Caring educators move beyond superficial or technical concerns and attempt to engage students in meaningful activities that validate their culture, language, and perspectives while supporting their academic and emotional needs. In order to clarify the nature of Care Theory and its applications to the classroom, theorists have suggested dichotomies of instructional delivery such as technical academic discourse vs. expressive academic discourse (Prillaman & Eaker, quoted in Valenzuela, 1999, p. 22) or aesthetic caring vs. authentic caring (Valenzuela, 1999). Instruction based merely on an aesthetic approach gives primacy to form and non personal content and only secondarily, if at all, [to] students subjective reality (Valenzuela, 1999, p. 22). An educator whose approach is based on expressive academic discourse and authentic caring brings trust, respect, and compassion into the classroom (Pang, 2005, p. 12). To appreciate the importance of Care Theory, one can imagine a child in a classroom where her home culture is ignored or degraded. That child is on guard to ward off the effects of the symbolic violence of the curriculum (Bourdieu, Calhoun, LiPuma, & Postone, 1993) or the impersonal, emotionally distant manner of the teacher. She may acquire new knowledge, but the learning process becomes more difficult because of the emotional energy she needs to survive her situation. Classrooms based on Care Theory allow students to take academic risks because they feel safe. Having familiarity with the culture and customs of the children, a caring teacher can decide whether to unobtrusively accommodate a student or to make her individual experience part of the whole-class curriculum.

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

12

When caring teachers treat students with dignity and respect, students are free to spend less time on emotional self-defense and more time on learning. It guides teachers toward humanistic approaches to instruction that nurture academic and affective growth. It clarifies the need to adapt the curriculum, to scrutinize texts for inaccuracies, and to modify daily activities. It also lays the groundwork for establishing respectful relationships with students and their families. Caring teachers recognize Arab and Muslim students as their children. Osterling and Fox (2004) offered the example of a powerful teaching moment one educator had with an Arabic-speaking ELL student in her predominantly Hispanic classroom: I have a student who is from a country that uses the Arabic alphabet who is minority in my class of mostly Central Americans her [Arabic] language is considered a low status minority language among [ELL] peers. She had come to the blackboard this morning to write her answer to a work problem and the rest of the class started to laugh at her as they watched her write in her labored child-like ways. I asked the class to be quiet and then asked her to please write the answer again but this time in Arabic. They watched quietly as she effortlessly wrote her beautiful script across the board. I then explained that learning English meant for this student that she also had to learn a completely new alphabet and style of writing as well as learn the pronunciation, grammar and vocabulary. I actually saw the light go on in the eyes of several of my students eyes as they realized the special challenges faced by their classmates. (p. 502)

Methodological Framework Selection of Participants Approximately 550 surveys were distributed to a convenience sampling pool from two educational institutions: Southwest Public Independent School District (SWPISD), a large school district in a metropolitan area; and Southwest University (SWU), a medium-sized university in the same metropolitan area. The district was selected because it contained the highest concentration of Arabic-

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

13

speaking students in the county: 117 out of 5100 total English Language Learners (ELL). The SWPISD group included staff and faculty from 5 elementary schools, 2 middle schools, and the central office, including the Bilingual/ESL department (n=131). The university group, entirely from the college of education, was composed of teaching faculty (n =87) from five departments and student teaching administrators. The number of surveys returned (n= 218) reflected the national trend in the teaching force: 79.8% female, 62.3 White. Procedure Instrumentation and Data Collection The present study had a mixed-methods design: the descriptive statistics (i.e., quantitive data presented by percentages) were complimented by qualitative data (i.e., written comments from participants). The studys mixed-methods design builds upon the complimentary strengths of qualitative and quantitative traditions (Gay, Mill, & Airasian, 2006, p. 11). A review of the extant literature revealed no studies focused on Arab-American students and their academic achievement in U.S. public schools (Al-Hazza & Lucking, 2005; Nieto, 2004; Suleiman, 1996) nor any instruments designed to ascertain data related to these students. For that reason, the first author designed an instrument called the Educators Cultural Awareness and Perceptions (E-CAP) surveyquestionnaire; the results of a pilot study in Spring 2006 determined this instruments content. The E-CAP survey-questionnaire included four sets of questions; the first two are the focus of this paper (see appendix A). Section A was designed to examine the participants knowledge of the terms Arab, Arabic, Islam and Muslim. Participants were asked to match each term with a definition in a fill-inthe-blank format. Section B, comprised of true-and-false questions, was designed to assess participants basic cultural knowledge about Arab-Americans. The E-CAP survey-questionnaire included one openended question (for qualitative data) that asked participants to write additional comments. Some participants wrote extensive marginal comments as well, and these proved to be a rich source of qualitative data.

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

14

Data Findings While the key terms Arabic, Islam, and Muslim each have a single definition, the term Arab can have multiple definitions. The following table presents the data that identifies the frequency of correct responses defining key terms (Arabic, Islam, and Muslim). Table 1. Frequency Table of Identifying the Terms Arabic, Islam, and Muslim. Percent of correct response (n=218) Correct Statements Arabic is a language. Islam is a religion. Muslim is a reference to people who follow the religion. Valid Percent 80.7% 74.8% 72.0%

According to Suleiman Arabs are individuals who speak Arabic and belong to the Semitic race with roots leading back to the Arabian Peninsula (quoted in Al-Hazza & Lucking, 2005, p. 4). From this definition Arab can be understood as a geographic or linguistic descriptor or both. Participants responded to questions to ascertain their understanding of the term (see Table 2). Table 2. Frequency Table of Identifying the Term Arab. Percent of correct response (n=218) Correct Statements Arab is: A reference to people who speak the language. Arab is: A reference to people with geographic roots in the Arabian Peninsula. Arab is: A reference to people who speak the language and 75.9% Valid Percent 17.2%

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

15

a reference to people with geographic roots in the Arabian Peninsula.

2.5%

The following table presents the frequency of true and false statements assessing participants basic knowledge of Arab-Americans and their cultures: Table 3. Frequency Table of True And False Questions. Percent of correct response (n=218) Statements True Eid al Fitr is a holiday. Ramadan is a holiday. All Arabs are Muslims. All Muslims are Arabs. Arab women have always had a secondary role in society. All Arabs living in America share the same culture and beliefs. Arabs/Muslims have made significant contributions to the 73.2% * U.S. culture. Note. Correct answers indicted by asterisks (*). 6.1% 20.7% 15.4% * 82.2% 1.4% 3.3% 36.2% .9 % Valid Percent False 8.4% 10.3% * 89.7% * 88.4% * 39.4% * 94.4% * Unsure 76.2% 7.5% 8.9% 8.4% 24.4% 4.7%

Discussion of Data For this study, participants were asked to respond to a series of questions to ascertain their understanding of basic ideas about Arab-American and Muslim-American students. The limited participants responses to them raise doubts about the extent to which educators are equipped to create

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

16

and maintain caring learning environments (Katz, Noddings, & Strike, 1999; Noddings, 2005) for their Arab-American students.

Terminology and Definitions Despite the respondents overall knowledge of the terms Arabic, Islam, and Muslim, the majority of educators (97.5%) did not recognize that the term Arab may have both a geographic and a linguistic meaning. Of the two hundred eighteen educators, only 2.5% identified the term Arab with both. Most educators (82.4%) identified the correct definition of the terms Arabic, Islam and Muslim, a result which reflects good cultural knowledge regarding these terms. This result may be due to the high educational level of the sample pool of educators, 95.0 % of whom held at least an undergraduate degree, and most of whom (71.5%) were teachers and college professors. The E-CAP survey results revealed that educators had varying levels of cultural knowledge about Arabs and Muslims, including knowledge of Muslim holidays. Approximately 83% of educators agree that they need to educate themselves about the classroom implications of some Islamic cultural practices, such as fasting during the month of Ramadan. The majority of respondents (89.7%) did not recognize that Ramadan is a lunar month in the Islamic calendar. In fact, approximately 82.0% of educators believed erroneously that Ramadan is a holiday, and 8.0% were unsure. Similarly, most educators (84.6%) did not recognize that Eid al Fitr is a holiday. Only 15.4% of educators found this statement to be true, and 76.2% were unsure. If educators know about fasting during the month of Ramadan, for example, they can create caring, culturally responsive environments for Muslim students and help these students observe fasting safely during school hours. Their familiarity with such customs would enable teachers to make appropriate accommodations, thus promoting student success. For example, Muslim students may want to abstain from rigorous physical exercises in their P.E. classes during Ramadan, completing alternative tasks instead (Shaikh, 2002). Also, Muslim students should not be forced to go to the cafeteria when fasting

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

17

(Ariza, 2006, p. 65). Educators can show sensitivity to fasting Muslim students by providing an alternative lunch-time location (Shaikh, 2002) such a library or computer lab (Ariza, 2006, p. 65). Teachers can also avoid scheduling tests on major Muslim holidays such as Eid al Fitr and Eid al Adha (Manning, 2005). These contradictory findings are evocative of the difference between technical discourse and humanistic discourse in education. Teachers report that empathy is essential but not enough on its own for working with culturally diverse students (McAllister and Irvine, 2002). Similarly, technical competence and subject matter knowledge are important (Kennedy, 1991) but insufficient alone. In practice, Care Theory unites knowledge, empathy, and willingness to create favorable learning environments for all students. To promote students academic and emotional development, teachers must move beyond a memorized list of multicultural ideas (technical discourse) and create learning experiences that incorporate and validate cultural accomplishments (humanistic discourse). As it concerns Arab or Muslim students, teachers must also have the willingness and courage to do the right thing despite its inconvenience or unpopularity.

Beliefs about the Role of Women and Gender When queried about the role of Arab women, only 39.4% of respondents indicated that Arab women have always had a secondary role in society was false (see table 3). Nearly as many (36.2%) believed the statement was true, while another 24.4% was unsure. Similarly, one of the surveyed educators wrote in a marginal note on the E-CAP survey-questionnaire: Arab boys need to show more respect for female teachers . (Aburumuh, 2007). Such beliefs reflect stereotypes of Middle Eastern males and overgeneralizations of conditions throughout the Muslim and Arab world. Sfeir (1985, p. 283) observed that the situation varies from country to country, from rural to urban areas, and depends on impact of Islamic resurgence, secularism, nationalism, Westernization and socialism. The original

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

18

teachings of Islam, actually favoring physical and spiritual development of both sexes, were overshadowed by other restrictive cultural influences. In some countries where misogynistic traditions are strong and modernization is limited, women may hold secondary roles (Baden, 1992). However, Islamic scholars argue that the Quran prescribes the spiritual equality of men and women (Baden, 1992, p. 4). According to Shah (2006) the Quran stresses justice between men and women: [the Quran] strongly guarantees fundamental rights without reserving them to men alone. The [Quran] does not make any distinction on the basis of sex and believes in human equality (Shah, 2006, p. 884). In general, the role of women in Islam has been misunderstood in the West because of general ignorance of the Islamic system and way of life as a whole, and because of the distortions of the media (Office of the Secretary General of Pakistan, 2008). In some Middle Eastern countries women drive their own vehicles, travel, complete university and professional studies, own their own business, are guaranteed suffrage, hold high government office, and live as mens spiritual and intellectual equals. According to Islamic principles, womenmarried or single, doctors or teachersare to be given respect. Caring educators will know that social constructs like gender roles will differ among cultures and will refrain from making value judgments based on limited knowledge or observations: Culturally competent practice requires knowledge, and nonjudgmental acceptance of the [students] cultural beliefs (Samantrai, 2004, p. 79). As they work to construct a safe, welcoming learning environment caring educators will blend the differing value systems of school and home (McDermott, 2008, p. 132).

Arab and Muslim Boys and Classroom Disruption The teacher cited above also wrote that Arab boys need to turn in written assignments, and follow rules regarding not talking out in class (E-CAP 75, 2006). A review of extant literature on Arab and Muslim students failed to produce any research on differentiated teacher beliefs about gender. However, extensive research provides evidence of teacher bias against males of color (Delpit, 1995;

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

19

Downey & Pribesh, 2004; Mickelson, 1990; Tyson, 2003). European-Americans and females are sanctioned differently or less frequently than males of color for committing the same wrong. Gay (2000) stated that classroom discipline is often expected to correlate strongly with student ethnicity, gender, and intellectuality (p. 59). Given the extensive research documenting anti-male and anti-minority sentiments in schools, it is logical to assume that the negative comment about Arab and Muslim boys is not limited to this teacher alone. According to Gay (2000), Gender interactionsare other crucial sites where academic achievement is either facilitated or obfuscated (p. 56). Some teachers expect males and students of color to create more classroom management problems and are vigilant for their infractions (Gay, 2000). Al-Khatab (1999) reported that students selfperception is influenced by their teachers expectations and perceptions. Mansouri and Kamp (2007) in their discussion of young Muslim Australians argue that if schools continue to penalize students because of their cultural or ethnic identities there is a danger that their educational outcomes will suffer, in turn impacting their ability to access the labour market and participate fully in civic life... (p. 88). Care Theory would argue that children taught under an ideology which expects them to be irresponsible with assignments, prone to being disrespectful to teachers, and sons of terrorists, would hardly feel nurtured or safe. Such children are subjects of symbolic violence, not members of a caring classroom.

Care Theory in the classroom: Practical applications Based on current research with multicultural classrooms we make the following suggestions for creating a caring environment for all childrenArab, Muslim, minority and majority. In a caring classroom, a mathematics teacher could create academic, humanistic discourse through discussions of the cultural origins and development of Arabic numerals system, the decimal system, and geometry. Students could write biographies on important Arabs or Muslims like al-Khwarazmi, the mathematician who created al-jaber (algebra) (Wingfield & Karaman, 2001; Wormser, 2002). Science students could learn

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

20

about Dr. Michael DeBakey, inventor of the heart pump, or Mohamed ElBaradei, Nobel Prize winner for atomic energy research. Students and teachers alike might be surprised to learn that Steve Jobs, co-founder and CEO of Apple computers, is Arab-American. In literature classes, (older) students could be assigned the novels of Naguib Mahfouz (Nobel Peace Prize winner for literature) or Khaled Hosseini, author of the Kite Runner and A Thousand Splendid Suns. A study of the achievements of popular entertainers like Shakira and Tony Shalhoub, or of athletes like Mohamed Ali, Doug Flutie, and Hakeem Olajuwon, would help students understand the many ways in which Arab Americans and Muslims contribute to American culture. We caution against add-ons or meaningless lists of famous people, festivities or foods (Banks, 2007; Banks & Banks, 2004; Lee, Menkart, & Okazawa-Rey, 2006). Caring teachers will purposefully weave or integrate the study of the positive contributions of Arab and Muslim cultures for their learners to foster a sense of familiarity with their cultures. In so doing, they will provide an antidote to the toxic stereotypes that assault the minds of mainstream students and victimize Arabs and Muslims of all ages and ethnicities (Said, 1997). Teachers are reminded to preview materials destined to the classroom for biases and inaccuracies. The following titles have been reviewed for appropriateness, accuracy and perspective. Shaikhs (2002) handbook Teaching about Islam & Muslims in the public school classroom is a valuable resource for exploring Islam and learning about the challenges facing Muslim students in U.S. public schools. Childrens literature is another invaluable resource to help teachers and students navigate beyond myths, misunderstanding, and stereotypes. Teachers who wish to introduce their students to Muslims may choose (for children) Chalfontes (1997) I am Muslim or (for adolescents), Wormsers (2002) American Islam: Growing up Muslim in America, or Islam: Eyewitness books (Wilkinson, 2005) and Celebrations (Kindersley, Kindersley, & Copsey, 1995). Selections of childrens fiction include

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

21

Naomi Shihab Nyes picture book Sittis Secrets (1997), or Rukhsana Khans (2002) Muslim Child: Understanding Islam through stories and poems.

Implications The results of this research indicate an urgent need for educators to examine their own perceptions and expectations of their students. Data reveal that educators have limited understanding of Arab and Muslim children, which leads to erroneous assumptions, pernicious beliefs, negative stereotypes and, ultimately, barriers to students education. Starting from a position of Care Theory as the guiding principle for education, we argue that far too much instructional delivery is reduced to superficial, aesthetic or technical education. According to Lee, Menkart and Okazawa-Rey (2006), multicultural education should help students, parents, teachers and administrators understand and relate the histories, cultures and languages of people different from themselves. But multicultural education must be much more than that. It must be transformative; that is, encourage academic excellence that embraces critical skills for progressive social change. (p.ix) Trumbull, Rothstein-Fisch, & Greenfield (2000) stated that educators must realize the necessity of social understanding of culture that goes beyond the relatively superficial aspects often addressed in multicultural education, such as major holidays, religious customs, clothing, and foods (Trumbull, et al., 2000). Educators need to develop cultural awareness and a deeper kind of understanding of social values and behavioral standards that shape approaches to child-rearing and family structure (Trumbull et al., 2000). Without a teachers professional and moral commitment to care for the whole child academically, emotionally, and culturallystudents cannot enjoy the full benefits and opportunities of American education. Teachers, as humans, may have unscientific nuisances as feelings, habits, conventions, associations, and values (Said, 1997, p. 164). However, if committed to become moral, caring professionals, teachers must seek in a disciplined way to employ reason and the information he or she

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

22

has gained through formal education.so that understanding may be achieved (Said, 1997, p. 164). Caring educators reflect on their feelings, attitudes and personal values to ensure that they do not inhibit the potentialities of the students. Although Arab and Muslim culture may be unknown or misunderstood, caring teachers will seek opportunities to learn about and experience these cultures. Caring teachers willingly problematize the beliefs they have about other cultures and ask for help from cultural insiders. In that way they demonstrate real respect for others and the professionalism necessary to create a caring classroom. In addition, caring educators are better able to modify pedagogy and curricula to fit their students needs, cultural backgrounds and learning styles and to consider cultural differences as assets. Although we advocated against the superfluous study of holidays, foods, and famous people, Arab and Muslim students require unique considerations for establishing caring relationships. Many Muslim practices extend beyond the place of worship and form an integral part of the daily lives of children and their parents. Prayers and fasting are two practices which educators should note. They usually occur during school hours and may conflict with school activities or scheduling. Coed sports, mandatory school uniforms that violate Islamic principles (e.g., gym shorts or swimsuits), and food-filled celebrations during times of fasting (e.g., Ramadan) may force children into avoidable emotional conflict. Again, caring educators invest their time to discover ways to create the most caring, welcoming and inclusive learning environment for all students. Whenever possible, teachers and schools must rely on the communication and involvement of Arab and Muslim parents and community members to create such an environment.

Conclusion Public schools are for all studentsArab and non-Arab; Muslim and non-Muslim. Care Theory tells us that it is possible to create learning environments in which students are given the necessary respect and support to do their best. Understanding and teaching Arab-American and Muslim students in U.S. public schools will require focusing attention in four broad dimensions: (1) understanding Arab and Islamic cultures; (2) eliminating negative stereotypes related to these cultures; (3) providing culturally

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

23

responsive teaching; and (4) maintaining caring relationships with Arab-American students and their families. Educators need to understand that the Arab-American population is diverse and heterogeneous; not all Arabs living in America share the same cultural practices, traditions and beliefs. And just as important, not all Muslims are Arabs and not all Arabs are Muslims. In order for educators to engage in authentic, caring relationships with Arab-American and Muslim students, we argue that it is imperative for them to move beyond the technical aspects of education toward more humanistic forms of academic engagement. Such experiences would recognize, validate and incorporate the multiple cultural, geographic, religious and linguistic identities in the Arab world. We also believe that in order to create these nurturing relationships, educators must be willing to expand their knowledge of all cultures. Care Theory is also an act of courage. Educators must problematize commonly held beliefs, assumptions, perspectives and privileges in order to create a welcoming, affirming, safe space for all students. As Shapiro (2005, p. 473) asserted: School exists not simply to prepare young people to fit in with what presently is but to encourage them to be passionate and active agents of change in our world. In this sense, education needs to be understood as more simply a mirror that reflects the exciting culture; it may also represent a light that directs our way to a more hopeful future.

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

24

Appendix A E-CAP Survey-Questionnaire: Section A & B LEARNING ABOUT CULTURES OTHER THAN YOUR OWN Arab-American Students in Public Schools: Assessing Educators' Cultural Awareness and Perceptions

Survey Questions A: Please choose the appropriate response(s) then fill in the blank. (The same response may be used more than one time.) 1- A reference to people who speak the language, 2- A religion, 3- A reference to people who follow the religion, 4- A language, 5- A reference to people with geographic roots in the Arabian Peninsula. 6- Unsure Arabic is : . Arab is : . Islam is : . Muslim is: .

B: Please choose True, False, or Unsure for the following statements. # 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Statements Eid al Fitr is a holiday. Ramadan is a holiday. All Arabs are Muslims. All Muslims are Arabs. Arab women have always had a secondary role in society. All Arabs living in America share the same culture and beliefs. Arabs/Muslims have made significant contributions to the U.S. culture. True Fals e Unsure

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

25

References AAI (2006). The Arab American Institute. Retrieved November, 2006, from http://www.aaiusa.org/ Aburumuh, H. (2007). Learning about cultures other than your own. Arab-American students in U.S. public schools: assessing educators cultural awareness and perceptions. The University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio. Adaptations for Special Populations, TEA State. (2007). Chapter 89. Retrieved Oct.10, 2007, from http://www.tea.state.tx.us/rules/tac/chapter089/ch089bb.html Al-Batal, M. (2006). Facing the crisis: teaching and learning Arabic in the United States in the postSeptember 11 Era. ADFL Bulletin, 37(2-3), 39-46. Al-Hazza, T., & Lucking, B. (2005). The minority of suspicion: Arab American. Multicultural Review, 14(3), 32-38. Al - Khatab, A. (1999). In search of equity for Arab-American students in public schools of the United States. Education 120(2), 254-266. Ariza, E. (2006). Not for ESOL teachers. Boston: Pearson Education, Inc. Baden, S. (1992). The position of women in Islamic countires: Possibilities, constraints and strategies for change (No. 4). Brighton: Institute of Development Studies. Banks, J. A. (2007). Educating citizens in a multicultural society (2nd ed.). New York: Teachers College Press. Banks, J. A., & Banks, C. A. M. (2004). Handbook of research on multicultural education (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Benet-Martinez, V., Leu, J., Lee, F., & Morris, M. (2002). Negotiating biculturalism: Cultural frame switching in biculturals with oppositional versus compatible cultural identities. Journal of CrossCultural Psychology, 33(5), 492-516. Bourdieu, P., Calhoun, C. J., LiPuma, E., & Postone, M. (1993). Bourdieu: Critical perspectives. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

26

Chalfonte, J. (1997). I am Muslim. New York: Rosen. Delpit, L. D. (1995). Other people's children : cultural conflict in the classroom. New York: New Press: Distributed by W.W. Norton. Downey, D., & Pribesh, S. (2004). When race matters: Teachers' evaluations of students' classroom behavior. Sociology of Education, 77(4), 267. Dwairy, M. (2004). Parenting Styles and Mental Health of Arab Gifted Adolescents. Gifted Child Quarterly 48(4), 275. Gay, G. (2000). Culturally responsive teaching New York: Teachers college press. Gay, L., Mills, G., & Airasian, P. (2006). Educational Research: Competencies for Analysis and Applications. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. Grant, C., & Ladson-Billings, G. (Eds.). (1997). Dictionary of multicultural education. Phoenix: Oryx. Heinrich, S. A. (1991). Code switching and contextual culture: The Indian model of stability maintenance. Unpublished Ph.D., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, United States -Illinois. Hovey, J. D., & Magana, C. G. (2000). Acculturative stress, anxiety, and depression among Mexican immigrant farmworkers in the Midwest United States. Journal of Immigrant Health, 2(3), 119. Katz, M. S., Noddings, N., & Strike, K. A. (1999). Justice and caring: the search for common ground in education. New York: Teachers College Press. Khan, R. (2002). Muslim child: Understanding Islam through stories and poems New York: Albert Whitman. Kennedy, M. (1991). Some Surprising Findings on How Teachers Learn to Teach. Educational Leadership, 49(3), 14-18. Kindersley, A., Kindersley, B., & Copsey, S. E. (1995). Children just like me. DK Publishing: New York.

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

27

Lee, E., Menkart, D., & Okazawa-Rey, M. (2006). Beyond heroes and holidays: A practical guide to K12 anti-racist, multicultural education and staff development. Washington, DC: Teaching for change. Manning, M. (2005). Understanding Arab American students. Journal, XVI(2), 14-18. Retrieved from http://www.nelms.org/pdfs/2005/journal/journal_winter_2005.pdf Mansouri, F., & Kamp, A. (2007). Structural deficiency or cultural racism: The educational and social experiences of Arab-Australian youth. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 42(1), 87. Mcallister, G., & Irvine, J. (2002). The Role of Empathy in Teaching Culturally Diverse Students: A Qualitative Study of Teachers Beliefs. Journal Of Teacher Education, 53 (5), 433-443. McDermott, D. (2008). Developing caring relationships among parents, children, schools, and communities. Los Angeles: Sage. Mickelson, R. (1990). The attitude-achievement paradox among black adolescents. Sociology of Education, 63(1), 44-61. Molinsky, A. L. (1999). Cross-cultural code switching. Unpublished Ph.D., Harvard University, United States -- Massachusetts. Molinsky, A. L. (2007). Cross-cultural code-switching: The psychological challenges of adapting behavior in foreign cultural interactions. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 622640. Naber, N. (2000). Ambiguous insiders: An investigation of Arab American invisibility. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 23(1), 37. Nieto, S. (2004). Affirming Diversity: The sociopolitical context of multicultural education. Boston: Pearson Education, Inc. Nieto, S. (2006). Multicultural education and school reform. In E. Provenzo (Ed.), Critical issues in education: An anthology of readings (pp. 228-244). Thousand Oaks, CA:: Sage. Noddings, N. (2005). The challenge to care in schools: an alternative approach to education (2nd ed.). New York: Teachers College Press.

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

28

Nydell, M. (2006). Understanding Arabs. Boston: Instructional Press. Nye, N. S. (1997). Sitti's secrets. New York: Aladdin, Simon & Schuster. Office of the Secretary General of Pakistan. (2008). Woman in Islam. Retrieved May 11, 2008, from http://www.jamaat.org/islam/WomanIslam.html. Ogbu, J. U., & Simons, H. D. (1998). Voluntary and Involuntary Minorities: A Cultural-Ecological Theory of School Performance with Some Implications for Education. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 29(2), 155-188. Osterling, J., & Fox, R. (2004). The Power of Perspectives: Building a Cross-cultural Community of Learners. International journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 7(6), 489505. Pang, V. (2005). Multicultural education - a caring-centered reflective approach. New York: McGrawHill. Pumariega, A., Rothe, E., & Pumariega, J. (2005). Mental health of immigrants and refugees. Community Mental Health Journal, 41(5), 581-597. Rainey, D., Morelli, J., & Hakki, M. (1999). Media and Image-building. Retrieved November, 2006, from http://www.alhewar.com/rainey.html Ryding, K. C. (2006). Teaching Arabic in the United States. In Z. A. T. Kassem M. Whaba, Liz England (Ed.), Handbook for Arabic language teaching professionals in the 21st century (pp. 13-20). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Said, E. W. (1997). Covering Islam : how the media and the experts determine how we see the rest of the world (Rev. ed.). New York: Vintage Books. Samantrai, K. (2004). Culturally competent public child welfare practice. Toronto, Canada: Thomson. Sapna, V. (2004). Exploring bicultural identities of Asian high school students through the analytic window of a literature club. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 48(1), 12. Sfeir, L. (1985). The status of Muslim women in sport: Conflict between cultural tradition and modernization. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 20(4), 283-306.

Educators Awareness and Perceptions of Arab-Americans

29

Shah, N. A. (2006). Women's human rights in the Koran: An interpretive approach. Human Rights Quarterly, 28(4), 868. Shaikh, M. (2002). Teaching About Islam and Muslims in the Public School Classroom: a Handbook for Educators, 3rd edition. California: Council on Islamic Education. Shapiro, S. (2005). Lessons of Septemper11: What should schools teach? In H. Shapiro & D. Purpel (Eds.), Critical social issues in American education (pp. 465-473). Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Soto, L. D. (2002). Making a difference in the lives of bilingual/bicultural children. New York: P. Lang Pub. Suleiman, M. (1996). Empowering Arab American students: Implications for multicultural teachers. Paper presented at the National Association for Multicultural Education, San Francisco. Trumbull, E., Rothstein-Fisch, C., & Greenfield, P. (2000). Bridging cultures in our schools: New approaches that work. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Tyson, K. (2003). Notes from the back of the room: Problems and paradoxes in the schooling of young black students. Sociology of Education, 76(4), 326. Valenzuela, A. (1999). Subtractive schooling : U.S.-Mexican youth and the politics of caring. Albany: State University of New York Press. Wilkinson, P. (2005). Islam (Eyewitness Books Series.) New York: DK Publishing, Inc. Wingfield, M., & Karaman, B. (1995). Arab Stereotypes and American Educators. Social Studies and the Young Learner, 7(4), 7-10. Wingfield, M., & Karaman, B. (2001). Arab stereotypes and American educators. In Beyond Heroes and Holidays: A Practical Guide to K-12 Anti-Racist, Multicultural Education and Staff Development, pp. 132-136. Washington, D.C.: Network of Educators on the Americas. Wormser, R. (2002). American Islam: Growing up Muslim in America. New York: Walker & Company. Zogby, J. (1982). When Stereotypes Threaten Pride. NEA Today, 12.

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Strategic Management Journal Oct 2003 24, 10 ABI/INFORM GlobalDocument5 pagesStrategic Management Journal Oct 2003 24, 10 ABI/INFORM GlobalSameer_Khan_60No ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Form I PSQADocument3 pagesForm I PSQASameer_Khan_60No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Peppers Rogers Customer Experience in Retail Banking ArticleDocument30 pagesPeppers Rogers Customer Experience in Retail Banking ArticleSameer_Khan_60No ratings yet

- Ramos-Rodriguez y Ruiz-Navarro (SMJ) Changes in The Intellectual Structure of Strategic Management Research A Bibliometric Study of The Strategic Management Journal (Original) - ScissoredDocument24 pagesRamos-Rodriguez y Ruiz-Navarro (SMJ) Changes in The Intellectual Structure of Strategic Management Research A Bibliometric Study of The Strategic Management Journal (Original) - Scissoredhomer_tokyoNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Total Quality Management (TQM) ToolsDocument84 pagesTotal Quality Management (TQM) ToolsSameer_Khan_60No ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- 00 NamesDocument107 pages00 Names朱奥晗No ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Journey Toward OnenessDocument2 pagesJourney Toward Onenesswiziqsairam100% (2)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Farhat Ziadeh - Winds Blow Where Ships Do Not Wish To GoDocument32 pagesFarhat Ziadeh - Winds Blow Where Ships Do Not Wish To GoabshlimonNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Breterg RSGR: Prohibition Against CarnalityDocument5 pagesBreterg RSGR: Prohibition Against CarnalityemasokNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- People Vs MaganaDocument3 pagesPeople Vs MaganacheNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Slavfile: in This IssueDocument34 pagesSlavfile: in This IssueNora FavorovNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- HRM in NestleDocument21 pagesHRM in NestleKrishna Jakhetiya100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Ati - Atihan Term PlanDocument9 pagesAti - Atihan Term PlanKay VirreyNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Vayutel Case StudyDocument10 pagesVayutel Case StudyRenault RoorkeeNo ratings yet

- Councils of Catholic ChurchDocument210 pagesCouncils of Catholic ChurchJoao Marcos Viana CostaNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Memorandum of Inderstanding Ups and GoldcoastDocument3 pagesMemorandum of Inderstanding Ups and Goldcoastred_21No ratings yet

- Impacts of Cultural Differences On Project SuccessDocument10 pagesImpacts of Cultural Differences On Project SuccessMichael OlaleyeNo ratings yet

- Direktori Rekanan Rumah Sakit Internasional 2015Document1,018 pagesDirektori Rekanan Rumah Sakit Internasional 2015Agro Jaya KamparNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Specific Relief Act, 1963Document23 pagesSpecific Relief Act, 1963Saahiel Sharrma0% (1)

- Spiritual Fitness Assessment: Your Name: - Date: - InstructionsDocument2 pagesSpiritual Fitness Assessment: Your Name: - Date: - InstructionsLeann Kate MartinezNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Mysteel IO Daily - 2Document6 pagesMysteel IO Daily - 2ArvandMadan CoNo ratings yet

- S0260210512000459a - CamilieriDocument22 pagesS0260210512000459a - CamilieriDanielNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - How To Calculate Present ValuesDocument21 pagesChapter 2 - How To Calculate Present ValuesTrọng PhạmNo ratings yet

- Ethical Dilemma Notes KiitDocument4 pagesEthical Dilemma Notes KiitAritra MahatoNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

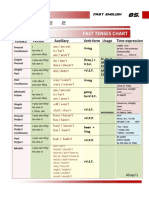

- Table 2: Fast Tenses ChartDocument5 pagesTable 2: Fast Tenses ChartAngel Julian HernandezNo ratings yet

- Impact of Money Supply On Economic Growth of BangladeshDocument9 pagesImpact of Money Supply On Economic Growth of BangladeshSarabul Islam Sajbir100% (2)

- PDF Issue 1 PDFDocument128 pagesPDF Issue 1 PDFfabrignani@yahoo.comNo ratings yet

- Chap 2 Human Resource Strategy and PerformanceDocument35 pagesChap 2 Human Resource Strategy and PerformanceĐinh HiệpNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Fundamentals of Product and Service CostingDocument28 pagesFundamentals of Product and Service CostingPetronella AyuNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship: The Entrepreneur, The Individual That SteersDocument11 pagesEntrepreneurship: The Entrepreneur, The Individual That SteersJohn Paulo Sayo0% (1)

- Engels SEM1 SECONDDocument2 pagesEngels SEM1 SECONDJolien DeceuninckNo ratings yet

- Mock 10 Econ PPR 2Document4 pagesMock 10 Econ PPR 2binoNo ratings yet

- Horizon Trial: Witness Statement in Support of Recusal ApplicationDocument12 pagesHorizon Trial: Witness Statement in Support of Recusal ApplicationNick Wallis100% (1)

- Assignment LA 2 M6Document9 pagesAssignment LA 2 M6Desi ReskiNo ratings yet

- Excursion Parent Consent Form - 2021 VSSECDocument8 pagesExcursion Parent Consent Form - 2021 VSSECFelix LeNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)