Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Indian Council Act

Uploaded by

paban2009Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Indian Council Act

Uploaded by

paban2009Copyright:

Available Formats

The Indian Council Act, 1892

The Indian council Act of 1892 introduced several reforms and significantly introduced the system of election.

The Indian constitution came into existence after the Act of 1861. The growth of the Indian constitution following Act of 1861 caused political disaffection and agitation alternating the Council reforms. The council reforms approved always found inadequate, hence stimulated disaffection and demand for the further reforms. The Legislative reforms created by the Acts of 1861, naturally though failed to meet the aspirations and the general demands of the people of the country. The element of non-officials, though small in number however did not represent the people. This group of non-officials belonged to the upper section or the aristocratic class of the Indian society. They consisted either of big zamindars, retired officials or Indian princess. These aristocrats were completely ignorant of the problems of the common people in India. During the later half of the 19th century the current of nationalist spirit began to emerge in India. The setting up of the universities in the presidencies led to the development of education. The use of English by the educated Indians brought then close to one another. The gulf betweens the Indians and the British in the field of the Civil Services incited the rage of the Indians. Moreover the repressive Acts made by Lord Rippon, the Vernacular Press Act and the Indian Arms Act in the year 1878, greatly exasperated the feelings of the Indians. The controversy between the Government of India and the Government of England over the abolition of 5% cotton duties made the Indians aware of the injustice of the British Government. As a whole the hollowness and the insincerity of the British government was revealed to the Indians. It was under these circumstances the Indian National Congress was formed in the year 1885. The sole motto of the congress was to organize the public opinions in India, thereby ventilate their grievances and demand reforms constitutionally. In the beginning though the attitudes of the British Governments to the Indian National Congress was friendly, yet by 1888, that attitudes changed when Lord Dufferin made a frontal attack on the Congress. Thus Lords Dufferin tried to belittle the importance of the representative characters of Congress. But he did not understand the significance of the movement launched by the congress. He secretly sent to England the proposals for liberalizing the Councils. He also appointed a committee of his council to prepare plans for the enlargement of the Provincial councils, for enhancement of their status, the multiplication of their functions, introduction of elective principles in the councils and the liberalization of their general character as political institutions. The report of the Committee was sent to the Home authorities in England proposing for the changes in the composition and functions of the Councils. The main aim of the reports was to give the Indian gentlemen wider share in the administration. The Conservative Ministry in England, introduced in the year 1890 a bill in the House of Lords on the basis of this proposals. But the measures adopted in the Bill were preceded very slowly and was passed two years later as the Indian Councils Act in the year 1892. The Indian council act of 1892, dealt exclusively with the powers, functions and the compositions of the Legislative councils in India. With regard to the Central Legislature, the Councils Act of 1892 provided that the number additional members must not be less than ten or more than sixteen. The increase of the members of the central Legislature was

described as a very paltry and miserable addition. But Curzon defended it on the ground that the efficiency of the deliberative body was not necessarily commensurate with the numerical strength. The council Act of 1892 upheld that two fifth of the total members council were to be non-officials. It had also been declared that non-officials were partly nominated and partly elected. The principle of election conceded to a limited extent. The Indian Council Act of 1892 increased the members of the Legislatures. These members were entitled to express their views upon the financial statements. The statement on the financial affairs henceforth was decided to be prepared on the Legislature. But these legislative members were not entitled to move resolutions or divide the houses in respect of any financial question. These legislative members were empowered to put questions with certain limits to the government on matters of interest after giving a six days notice. Regarding the provincial Legislature the Council Act enlarged the number of additional members to not less than eight or more than twenty in case of Bombay and Madras. The maximum for Bengal was also fixed at twenty. But for the northwestern province and Oudh, the number was fixed at fifteen. The members of the Provincial Legislature had to perform several functions. Their Chief function was to secure the interpellation of the executive in the matters of the general public interest. They could also discuss the policy of the government and ask questions, which required a thorough previous notice. Their questions could also be disallowed by the central government if necessary without assigning any reason. The Indian Councils Act of 1892 introduced several new rules and regulations. However the significant feature of this Indian council Act was the procedures of election it introduced, though the word election was very carefully avoided in it. The Act envisaged that apart from the elected official members there should be elected non-official members, whose number was to be five. The non-official members of the Council were one to be elected by each of the nonofficial member of the four Provincial legislatures of Bombay, Madras and Calcutta and the Northwestern province and one by the Calcutta Chamber of Commerce. The governor general nominated the other five non-officials himself. Ins cases of Provincial Legislatures, the bodies permitted to elects the members of Municipalities, District Boards, Universities ands the Chamber of commerce. The methods of election however were not mentioned in the clear terms. The "elected" members were officially declared as "nominated" although after taking into consideration the recommendation of each body. These Legislative bodies met in several sessions in order to prepare recommendations to the governor general or head of the Provincial Government. The person favored by the majority was not described as the "elected", rather they were directly recommended for nomination. The Indian Councils Act of 1892 was undoubtedly an advance on the Act of 1861. The Act of 1892 widened the functions of the legislature. The members could ask questions ands thus obtain information, which they desired, from the executive. The Councils Act of 1892 made it obligatory that the financial accounts of the currents year and the budget for the following year should be presented in the legislature. The members were permitted to make general observations and on the budget and make suggestions for increasing or decreasing revenue and expenditure. Apart from these the recognition of the principle of election introduced by the Acts of 1892, was a measure of constitutional significance. However there were several defects and shortcomings in the Acts of 1892 by the reason of which the Act failed to satisfy the Indians nationalists. The Act was criticized at successive sessions of the Indian national Congress. Critics haves opined that the procedure of election was a roundabout one. This was so because

though theoretically the process of election was followed, in actuality these local bodies were the nominated members. Moreover the function of the legislative councils was strictly circumscribed. In conclusion it can be said that despite the fact that the Indian councils Act of 1892 fell far short of the demands made by the Indian National Congress, yet it was undoubtedly a great advance on the existing state of things.

You might also like

- Human Rights and Intellectual Property - Conflict or CoexistenceDocument16 pagesHuman Rights and Intellectual Property - Conflict or Coexistencepaban2009No ratings yet

- BlueScreen Problem on Windows 6.1Document1 pageBlueScreen Problem on Windows 6.1paban2009No ratings yet

- Main UN Bodies Quick FactsDocument2 pagesMain UN Bodies Quick Factspaban2009No ratings yet

- Indian Councils Act, 1861 (24 & 25 Victoria, C. 67)Document13 pagesIndian Councils Act, 1861 (24 & 25 Victoria, C. 67)AJEEN KUMAR100% (1)

- Economic Development Economic Growth: Comparison ChartDocument1 pageEconomic Development Economic Growth: Comparison Chartpaban2009No ratings yet

- Development of Indian Constitution During British EraDocument21 pagesDevelopment of Indian Constitution During British Erapaban2009No ratings yet

- Factors Driving Economic DevelopmentDocument5 pagesFactors Driving Economic Developmentpaban2009100% (1)

- Absolute LiabilityDocument2 pagesAbsolute Liabilitypaban2009No ratings yet

- The Six Main UN OrgansDocument3 pagesThe Six Main UN Organspaban2009No ratings yet

- Indian Councils Act of 1909Document4 pagesIndian Councils Act of 1909paban2009No ratings yet

- Factors Driving Economic DevelopmentDocument5 pagesFactors Driving Economic Developmentpaban2009100% (1)

- EcoDocument3 pagesEcopaban2009No ratings yet

- Marriage Under MuslimDocument15 pagesMarriage Under Muslimpaban2009No ratings yet

- Free Trade Policy: Free Trade Occurs When There Are No Artificial Barriers Put in Place by Governments To RestrictDocument3 pagesFree Trade Policy: Free Trade Occurs When There Are No Artificial Barriers Put in Place by Governments To Restrictpaban2009No ratings yet

- Economic Development Economic Growth: Comparison ChartDocument1 pageEconomic Development Economic Growth: Comparison Chartpaban2009No ratings yet

- 299 and 300Document2 pages299 and 300paban2009No ratings yet

- David Samuel - All Is MindDocument41 pagesDavid Samuel - All Is MindahreanuluiNo ratings yet

- Indian Councils Act of 1892 (55 & 56 Vict. C. 14)Document3 pagesIndian Councils Act of 1892 (55 & 56 Vict. C. 14)AJEEN KUMARNo ratings yet

- Govt of India Act 1858Document7 pagesGovt of India Act 1858AJEEN KUMAR100% (1)

- Read MeDocument1 pageRead Mepaban2009No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument1 pageUntitledpaban2009No ratings yet

- The Criminal Law Amendment Ordinance, 1944Document11 pagesThe Criminal Law Amendment Ordinance, 1944Soumyadeep MitraNo ratings yet

- Pillar Iii As On 31ST December 2010Document4 pagesPillar Iii As On 31ST December 2010Hinal TejaniNo ratings yet

- Sun RiseDocument1 pageSun Risepaban2009No ratings yet

- Higher Algebra - Hall & KnightDocument593 pagesHigher Algebra - Hall & KnightRam Gollamudi100% (2)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- France's Semi-Presidential System ExplainedDocument6 pagesFrance's Semi-Presidential System ExplainedDaphnie CuasayNo ratings yet

- Constitutional and Political Development in Pakistan-1Document37 pagesConstitutional and Political Development in Pakistan-1Yawar ShahNo ratings yet

- Hobbes LockDocument2 pagesHobbes Lockhaya bisNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law II MCQ BSL IVDocument14 pagesConstitutional Law II MCQ BSL IVAnand100% (1)

- Sample Constitution and BylawsDocument7 pagesSample Constitution and BylawsSummerRain67% (3)

- Dudgeon v. The United KingdomDocument42 pagesDudgeon v. The United KingdomMariam KotolashviliNo ratings yet

- Role of Comptroller and Auditor General of IndiaDocument11 pagesRole of Comptroller and Auditor General of IndiaRaaj KumarNo ratings yet

- Admin Law AssignmentDocument16 pagesAdmin Law AssignmentNilotpal RaiNo ratings yet

- RPF SI 06-Jan-2019 - Shift - 1 QuestionDocument31 pagesRPF SI 06-Jan-2019 - Shift - 1 QuestionKiran KotteNo ratings yet

- The Principles of The French ConstitutionDocument7 pagesThe Principles of The French ConstitutionsharmanakulNo ratings yet

- The Anti-Suffragist PapersDocument5 pagesThe Anti-Suffragist Papersraunchy4929No ratings yet

- Sir Benjamin Stone's Pictures - Records of National Life and History - Vol. I - Festivals, Ceremonies, and CustomsDocument390 pagesSir Benjamin Stone's Pictures - Records of National Life and History - Vol. I - Festivals, Ceremonies, and CustomsSergio MotaNo ratings yet

- Sen. Pete Domenici Special SectionDocument12 pagesSen. Pete Domenici Special SectionAlbuquerque Journal100% (1)

- Risley Theatre Charter: I. EstablishmentDocument12 pagesRisley Theatre Charter: I. Establishmentjuskeepswimmin72No ratings yet

- CANADADocument21 pagesCANADARASHI SETHI-IBNo ratings yet

- 2050 PDFDocument98 pages2050 PDFOanaVoichiciNo ratings yet

- The Nature of The Constitution of UK Is Unwritten''-Do You Agree?Document8 pagesThe Nature of The Constitution of UK Is Unwritten''-Do You Agree?HossainmoajjemNo ratings yet

- Northern Research GroupDocument2 pagesNorthern Research GroupTeam GuidoNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law 2011Document5 pagesConstitutional Law 2011qanaqNo ratings yet

- Tanzania 2010-2011 BudgetDocument55 pagesTanzania 2010-2011 BudgetSubiNo ratings yet

- Peace Researcher Vol2 Issue11 Dec 1996Document20 pagesPeace Researcher Vol2 Issue11 Dec 1996Lynda BoydNo ratings yet

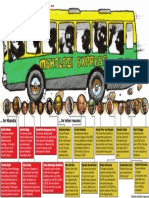

- Thrown Under The BusDocument1 pageThrown Under The BusCityPress100% (2)

- Right of Children To Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009Document21 pagesRight of Children To Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009nibha rani barmanNo ratings yet

- Test Bank Global Health 101 2nd Edition by Richard SkolnikDocument34 pagesTest Bank Global Health 101 2nd Edition by Richard Skolnikyautiabacchusf4xsiy100% (28)

- Arroyo vs. de VeneciaDocument2 pagesArroyo vs. de VeneciaJade ViguillaNo ratings yet

- (CONSTI) Astorga Vs Villegas DigestDocument2 pages(CONSTI) Astorga Vs Villegas DigestMarc VirtucioNo ratings yet

- PSPCL Lower Division Clerk Provisional Merit ListDocument4,265 pagesPSPCL Lower Division Clerk Provisional Merit ListRiya MahajanNo ratings yet

- Philippine legislative process and powersDocument2 pagesPhilippine legislative process and powersNorbea May Rodriguez100% (1)

- Administrative rulemaking and adjudication explainedDocument5 pagesAdministrative rulemaking and adjudication explainedShailvi RajNo ratings yet

- En Banc ruling on constitutionality of Fair Election Act provisionDocument7 pagesEn Banc ruling on constitutionality of Fair Election Act provisionJoyce Manuel100% (1)