Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Camus' Philosophy of Rebellion Against the Absurd

Uploaded by

Dhei TomajinOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Camus' Philosophy of Rebellion Against the Absurd

Uploaded by

Dhei TomajinCopyright:

Available Formats

Albert Camus: Rebelling Against the Absurd

If human life is absurd, empty, meaningless, leading only to death, can anything of value be rescued from it? If we are thrown into a completely desolate and forlorn existence, why do anything? Why not kill ourselves now instead of waiting for the final absurdity of death to take us? Albert Camus (1913-1960) maintained in his own life a tension between this awareness of the futility of human existence and his own defiant, rebellious self-affirmation. His writings (philosophy and fiction) reflect and illustrate this paradox: Altho ultimate and lasting meaning is impossible, we can still create our own dignity as persons by challenging the absurd. A strange love of life emerges from a devastating encounter with despair, as John Cruickshank explains in his book on Camus: His inquiry, which set out to discover how the absurd paradox might either be solved or destroyed ends by making this paradox itself the basis for positive action.... Camus derives meaning for his existence from an original denial of the possibility of meaning.... Camus takes as his key to existence the very fact of not having a key. Cruickshank distinguishes four ways in which we notice the absurd: 1. We might feel the absurd when something interrupts our daily routine, when our comfortable, automatic, habitual ways of life suddenly fall apart and we are forced to ask the deepest possible why? 2. The absurd might intrude into our smooth-flowing consciousness when we become acutely aware of the passage of time: Life becomes transparent to its end, and we see that it adds up to zero. 3. Sometimes familiar objects become radically alien and strange. We discover ourselves exiled in an accidental world that makes no sense. 4. Our separation from other people, our estrangement from ordinary life, might open us to the deep clash and disharmony of existence. We see normal human behavior as shallow, empty, mechanical, senseless.

Albert Camus: Philosopher of the Absurd Albert Camus (1913-1960), novelist, dramatist, philosopher, essayist, was born in Algeria on 7 November, 1913. His mother was Spanish and his Breton father was killed in World War I in 1914. Camus was raised and studied under difficult but reasonably happy circumstances: though I was born poor, I was born under a happy sky in a natural setting with which one feels in union, unalienated. Initially a journalist in Algiers, and later in Paris, he was Editor of Combat, the underground resistance newspaper from 1942 to 1946. Camus, like his friends Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, was then an active member of the resistance. He was but 46 when he was killed instantly in a road accident in January 1960, having been offered a lift back to Paris by a close friend (Roger Gallimard, the publisher, who later died of injuries sustained in the crash). The Nobel prize for literature was awarded to Camus in 1957. Whilst his major interest was mainly in literature, he studied philosophy at Algiers University, and wrote didactic texts which are certainly philosophical. In philosophical histories or dictionaries he is usually listed under French existentialism and accorded higher status, as philosopher, than Simone de Beauvoir. Camus rejected the category existentialist. For many years a friend of Jean-Paul Sartre and Beauvoir they were to experience a massive falling out. But this had earlier roots, to do with jealousy, with Camus fierce individualism, combined with a post political ethics, and a refusal to commit himself politically to causes at a time after WW II when Sartre, under the influence of Beauvoir, was moving away from his earlier violent and alienated notion of the individual. The final straws were probably Sartre siding with the Communists (Camus would have no truck with them), an intemperate review of LHomme Rvolt in Les Temps Modernes, and an equally intemperate reply by Camus. Sartre responded equally as badly to Camus in Les Temps Moderne (August, 1952): you may be my brother brotherhood is cheap you certainly arent my comrade (Sartre, 1952). (But they had been comrades in the resistance). Camus had enormous consideration for others and was extremely generous, perhaps to a fault. In his early days Beauvoir said that she liked the hungry ardour of their companion, yet that he could become concerned that his generosity was received with ingratitude. He could become formal in discussion if not righteous and, pen in hand, he became a rigid moralist (Beauvoir, 1968: p.61). Perhaps the acclaim and his good luck went to his head. Nor as moralist did he have time for the deliberations and the risks involved in translating his moralism into political thought

and action. In his later life he was probably closer to Gaullism than socialism, refusing to denounce colonialism in Algeria in Stockholm were he was to be awarded his Nobel prize. But in an ever increasing modernism and performativity Camus traces the disappearance of old Europe and the spaces where morals and justice are being replaced by the spaces of new technologies. The essential philosophical thought of Camus is to be found in Le Myth de Sisyphe(1943) (The Myth of Sisyphus [1943]) and LHomme Rvolt (1951) (Transl. into English as The Rebel [1969]) although there are differen ces and developments between the two. These ideas are of course explored in his novels. A major thesis of Camus, in both tracts, is the problematisation of death. In the earlier tract it is suicide and in the latter it is the death of others, especially murder. They do not involve studies of death but, instead, attitudes towards death. If we can have experience of other things we cannot experience death, Camus argues for, at best, any experience is second hand and parasitic. Camus ongoing point is that we can have no experience of death, in the sense that we experience sense data, emotions, etc., but that death is, as human beings, our only certainty. He has been titled as the writer of the absurd which, in his thought, can be described as the confrontation between our human demands for justice and rationality with a contingent and indifferent universe. Hence life is meaningless. Yet, we must accept the absurdity of life and we must go on living Sisyphus accepts his futile fate. But: Finally I come to death. In Le Myth de Sisyphe absurdity is a sensation or feeling, which seizes us suddenly. It is at the base of thought and action, even though it is indeterminate and confused and, if present, it is distant in time. Time is our worst enemy, causing us to place ourselves in time, and live with the future in mind we are ardent for tomorrow even though much of life is mechanical repetition. Faced by the absurdity of life consciousness becomes crucial to Camus thought it is the only good and the real good. It permits one to discern meaning and, as the world has no meaning, it is ultimately absurd (though it is the relationship between consciousness and the world which is said to be absurd). Our reaction to this experience of absurdity is pursued in L'Homme Rvolt. Metaphysical rebellion is the answer to absurdity. It is the means by which a man protests against his condition and against the whole of creation it disputes the ends of man and creation (it) protests against the human condition ( The Rebel, p.29). Rebellion indefatigably confronts evil. But it also sets limits, beyond which one cannot go, for rebellion without limits ends in slavery: he who dedicates himself to the duration of his life, to the house he builds, to the dignity of mankind, dedicates himself to the earth and sustains the world again and again (ibid., p. 267). There is then a message of hope in rebellion because consciousness can make the walls or limits that could not formerly be penetrated, transparent. Consciousness is promoted by the absurd. There is a promise of a real awakening and no chance of returning to repose. But here Camus stops. There are no principles which define an appropriate rebellion. He is not so much theoretical here but practical. Each situation is new and the appropriate action determined by analysis of that situation. Camus was against violence but under certain conditions the rebel would choose limited and brief violence. On the eve of the liberation of Paris in WW II, he wrote in Combat: the barricades of freedom have once more been thrown up. Once more justice must be bought with the blood of men their reasons must then have been overwhelming for them suddenly to seize the guns and shoot steadily, in the night, at those soldiers who for two years thought that war was easy (Camus, 1944). There are limits then between opposites and moderation is the key. There are dualisms such as life and death; love and hatred; tenderness and justice; and justice for man against the contingenci es of history. Somewhat paradoxically the rebel must at one and the same time reject and accept history, and simultaneously deny and affirm. Camus always sought a middle path, an equilibrium, and moderation. But without principles for such moderate forms of rebelling Camus seems almost anarchistic. This concept of absurdity of the human condition is to be found in the Theatre of the Absurd which uses a variety of dramatic techniques which defy rational analysis in their presentation of the absurdity of the human condition. The term was coined by Martin Esslin in 1961 but he developed the notion of the absurd from Camus Le Myth de Sisyphe. Dramatists to whom this title might be applied include Eugene Ionesco, Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter. Talking of the death of her former friend Simone de Beauvoir was to say: it wasnt the fifty-year old man whod just died I was mourning; not that just man without justice, so arrogant and touchy behind his stern mask it was the companion of our hopeful years, whose open face laughed and smiled so easily, the young ambitious writer, wild to enjoy life, its pleasures, its triumphs and comradeship, friendship, love and happiness. Death had brought him back to life; for him time no longer existed (Beauvoir, 1968, p.497). Sartre in a eulogy for him in France-Observateur on 7 January 1960 said: He was, in this century and against history, the current heir to that long line of moralists whose works perhaps constitute that which is most original in French letters. His stubborn humanism, narrow and pure, austere and sensual, battled uncertainly against the massive and misshapen events of this our time. But, inversely, through his obstinate refusal, he reaffirmed, in the heart of our era, against the Machiavellians, against the golden calf of realism, the existence of morality

You might also like

- The Myth of Sisyphus by Albert Camus (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideFrom EverandThe Myth of Sisyphus by Albert Camus (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- Camus' The Myth of Sisyphus Book ReviewDocument17 pagesCamus' The Myth of Sisyphus Book ReviewEthyl Mae Alagos-VillamorNo ratings yet

- Cam UsDocument6 pagesCam UsJacqueCheNo ratings yet

- The Myth of Sisyphus SummaryDocument9 pagesThe Myth of Sisyphus SummarySean Patrick RazoNo ratings yet

- Albert Camus' Philosophy of Absurdism and the Existentialist Themes in His WorksDocument5 pagesAlbert Camus' Philosophy of Absurdism and the Existentialist Themes in His WorksAi MllrNo ratings yet

- Camus and the AbsurdDocument1 pageCamus and the AbsurdtruciousNo ratings yet

- Myth of SisyphusDocument3 pagesMyth of SisyphusPaliwalharsh8No ratings yet

- Trabajo 490 BorradorDocument6 pagesTrabajo 490 BorradorMariaNo ratings yet

- Albert Camus A Literary GeniusDocument39 pagesAlbert Camus A Literary GeniusAmjad AliNo ratings yet

- The Myth of Sisyphus ExplainedDocument2 pagesThe Myth of Sisyphus ExplainedsweetyjoNo ratings yet

- Albert Camus: The Absurd Hero: Bob LaneDocument5 pagesAlbert Camus: The Absurd Hero: Bob LanesanamachasNo ratings yet

- Albert CamusDocument13 pagesAlbert Camusiqra khalidNo ratings yet

- Albert Camus:: Illuminating The Problem of The Human Conscience in Our TimeDocument13 pagesAlbert Camus:: Illuminating The Problem of The Human Conscience in Our Timerazor_razor100% (1)

- Myth of SisyphusDocument4 pagesMyth of SisyphusAravind SethumadhavanNo ratings yet

- Camus's La Peste Explores Individuality Within CommunityDocument5 pagesCamus's La Peste Explores Individuality Within CommunityTim EarlyNo ratings yet

- Is Life Meaningless. and Other Absurd QuestionsDocument2 pagesIs Life Meaningless. and Other Absurd Questionszara21No ratings yet

- Is Life Meaningless - Ted EdDocument2 pagesIs Life Meaningless - Ted EdNguyễn Hà Phương Vy - NTMKNo ratings yet

- The Philosophy of Absurdism (Essay)Document3 pagesThe Philosophy of Absurdism (Essay)Marinelle AtienzaNo ratings yet

- Movement Origin - :: Absurdism Is A Type of Philosophy Which Means The Internal Conflict Between Human Tendency To FindDocument4 pagesMovement Origin - :: Absurdism Is A Type of Philosophy Which Means The Internal Conflict Between Human Tendency To FindHusnain AteeqNo ratings yet

- Albert Camus ReportDocument21 pagesAlbert Camus ReportWinston QuilatonNo ratings yet

- Albert Camus EssayDocument5 pagesAlbert Camus Essayafefihsqd100% (1)

- AbsurdityDocument30 pagesAbsurdityMonjur ArifNo ratings yet

- Freedom Passion and Resistance On The Intention ofDocument5 pagesFreedom Passion and Resistance On The Intention ofNegru CorneliuNo ratings yet

- Document For Review RevisedDocument19 pagesDocument For Review RevisedFrancis Robles SalcedoNo ratings yet

- Absurdism: Dramatists Writing and Producing Plays in TheDocument4 pagesAbsurdism: Dramatists Writing and Producing Plays in TheNaveed AkhterNo ratings yet

- Hemingway's Existential Ending: Tung Chung-HsuanDocument15 pagesHemingway's Existential Ending: Tung Chung-HsuanpetrichorNo ratings yet

- Complete AssignmentDocument6 pagesComplete AssignmentZojaan AheerNo ratings yet

- Camus in 60 Minutes: Great Thinkers in 60 MinutesFrom EverandCamus in 60 Minutes: Great Thinkers in 60 MinutesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- Does Essence Precede Existence? A Look at Camus's Metaphysical RebellionDocument7 pagesDoes Essence Precede Existence? A Look at Camus's Metaphysical RebellionYami CámeraNo ratings yet

- Albert Camus (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)Document14 pagesAlbert Camus (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)Shreyas JoshiNo ratings yet

- Absurdism in "The Outsider": Ruoqi HanDocument5 pagesAbsurdism in "The Outsider": Ruoqi HanDebdeep RoyNo ratings yet

- Albert Camus and the Philosophy of AbsurdismDocument4 pagesAlbert Camus and the Philosophy of AbsurdismJamie HurstNo ratings yet

- Albert Camus Was A FrenchDocument2 pagesAlbert Camus Was A Frenchdoan anhNo ratings yet

- Asdsdasdijvgrj 3123Document1 pageAsdsdasdijvgrj 3123stoneoaklogsNo ratings yet

- Law and Literature: The Absurd in Law in The Stranger by Albert CamusDocument18 pagesLaw and Literature: The Absurd in Law in The Stranger by Albert CamusShivam ShreshthaNo ratings yet

- The Theater of the Absurd and ExistentialismDocument13 pagesThe Theater of the Absurd and ExistentialismChristopher HintonNo ratings yet

- Albert Camus and The Ethics of Moderation: Lana StarkeyDocument17 pagesAlbert Camus and The Ethics of Moderation: Lana StarkeyDanielle John V. MalonzoNo ratings yet

- Journal of Camus Studies 2019From EverandJournal of Camus Studies 2019Peter FrancevNo ratings yet

- The Myth of SisyphusDocument33 pagesThe Myth of SisyphusGio SanchezNo ratings yet

- KRITY'S FINAL PROJ '24Document29 pagesKRITY'S FINAL PROJ '24sharma.harshita2019No ratings yet

- ExstitentialismDocument2 pagesExstitentialismAdnanSmajićNo ratings yet

- Fromm and Camus Psycho-Social Illness PDFDocument9 pagesFromm and Camus Psycho-Social Illness PDFskanzeniNo ratings yet

- Camus' Search for MeaningDocument15 pagesCamus' Search for MeaningSasha VDCNo ratings yet

- Sin without God': Existentialism and The TrialDocument17 pagesSin without God': Existentialism and The TrialAmrutha100% (1)

- L'Esprit Créateur, Volume 50, Number 2, Summer 2010, Pp. 158-160 (Review)Document4 pagesL'Esprit Créateur, Volume 50, Number 2, Summer 2010, Pp. 158-160 (Review)Vivien MadsonNo ratings yet

- Albert Camus and The Phenomenon of SolidarityDocument83 pagesAlbert Camus and The Phenomenon of SolidarityJeremy MolinaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Existentialism: Literature and PhilosophyDocument40 pagesIntroduction To Existentialism: Literature and PhilosophyFitz BaniquedNo ratings yet

- Albert Camus PresentationDocument7 pagesAlbert Camus Presentationamedlin810No ratings yet

- The Philosophy of Absurdity in The StrangerDocument8 pagesThe Philosophy of Absurdity in The StrangerMahrukh MalikNo ratings yet

- Albert Camus and Existentialism A Comprehensive Exploration of Absurdism and BeyondDocument3 pagesAlbert Camus and Existentialism A Comprehensive Exploration of Absurdism and BeyondNigel GaleaNo ratings yet

- 08 Chapter3 BDocument47 pages08 Chapter3 BMarina MikshaNo ratings yet

- PHILOSOPiyygwdceaDocument66 pagesPHILOSOPiyygwdceaJonarry RazonNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument6 pagesAnnotated Bibliographysmei91No ratings yet

- The Absurd Hero in AmericanDocument15 pagesThe Absurd Hero in AmericanjauretNo ratings yet

- Albert Camus' PhilosophyDocument3 pagesAlbert Camus' PhilosophyPatricia Jane PereyNo ratings yet

- LAS Addition of FractionsDocument7 pagesLAS Addition of FractionsDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Go To Grade 5 Everyday Mathematics Sample LessonDocument22 pagesGo To Grade 5 Everyday Mathematics Sample Lessonshaira de leonNo ratings yet

- Module 16 Terminating and Non Terminating DecimalsDocument4 pagesModule 16 Terminating and Non Terminating DecimalsDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Module 13-Division of FractionsDocument8 pagesModule 13-Division of FractionsDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Dividing Decimals by 0.1, 0.01, and 0.001Document2 pagesDividing Decimals by 0.1, 0.01, and 0.001Dhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Module 3 SERIES OF OPERATIONSDocument7 pagesModule 3 SERIES OF OPERATIONSDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Module 15 Division of Fractions Word ProblemsDocument2 pagesModule 15 Division of Fractions Word ProblemsDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Module 16 Terminating and Non Terminating DecimalsDocument4 pagesModule 16 Terminating and Non Terminating DecimalsDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Module 13-Division of FractionsDocument8 pagesModule 13-Division of FractionsDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Go To Grade 5 Everyday Mathematics Sample LessonDocument22 pagesGo To Grade 5 Everyday Mathematics Sample Lessonshaira de leonNo ratings yet

- Module 15 Division of Fractions Word ProblemsDocument2 pagesModule 15 Division of Fractions Word ProblemsDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Module 14-Division of Decimals 2Document2 pagesModule 14-Division of Decimals 2Dhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Module 4-DIVISION OF FRACTIONSDocument8 pagesModule 4-DIVISION OF FRACTIONSDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Module 6 - ADDITION OF DECIMALSDocument3 pagesModule 6 - ADDITION OF DECIMALSDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Divisibility Rules 4, 8, 12, 11Document7 pagesDivisibility Rules 4, 8, 12, 11Dhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Module 2-Multiplication of FractionsDocument9 pagesModule 2-Multiplication of FractionsDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Guidance and Counselling Service Individual Inventory RecordDocument3 pagesGuidance and Counselling Service Individual Inventory RecordDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Module 5-GCF LCMDocument7 pagesModule 5-GCF LCMDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Favorite Sporting Activities Circle GraphDocument1 pageFavorite Sporting Activities Circle GraphDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Block Model-LacDocument22 pagesBlock Model-LacDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- 1STQ MathDocument5 pages1STQ MathDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

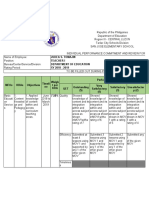

- Automated IPCRFDocument71 pagesAutomated IPCRFDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Leadership Styles and Employee Commitment in Private Higher Education Institutions at Addis Ababa City PDFDocument76 pagesThe Relationship Between Leadership Styles and Employee Commitment in Private Higher Education Institutions at Addis Ababa City PDFDhei Tomajin100% (2)

- Module 1-Divisibility RulesDocument7 pagesModule 1-Divisibility RulesDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- The Number 4 Is The Only Number That Has The Same Number of Letters in ItDocument6 pagesThe Number 4 Is The Only Number That Has The Same Number of Letters in ItDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Responsibility ChartDocument1 pageResponsibility ChartDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Faces KidsDocument6 pagesFaces KidsDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Labels For The RoomDocument7 pagesLabels For The RoomDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Computer Assisted InstructionDocument2 pagesComputer Assisted InstructionDhei TomajinNo ratings yet

- Code of Ethics For Teachers PDFDocument10 pagesCode of Ethics For Teachers PDFMevelle Laranjo AsuncionNo ratings yet

- Reflection 2: WHAT DOES It Mean To Be A Pacific Islander Today and in The Future To Me?Document5 pagesReflection 2: WHAT DOES It Mean To Be A Pacific Islander Today and in The Future To Me?Trishika NamrataNo ratings yet

- Drugs Pharmacy BooksList2011 UBPStDocument10 pagesDrugs Pharmacy BooksList2011 UBPStdepardieu1973No ratings yet

- CANAL (T) Canal Soth FloridaDocument115 pagesCANAL (T) Canal Soth FloridaMIKHA2014No ratings yet

- Chapter 16 - Energy Transfers: I) Answer The FollowingDocument3 pagesChapter 16 - Energy Transfers: I) Answer The FollowingPauline Kezia P Gr 6 B1No ratings yet

- Steam Turbines: ASME PTC 6-2004Document6 pagesSteam Turbines: ASME PTC 6-2004Dena Adi KurniaNo ratings yet

- 5125 w04 Er PDFDocument14 pages5125 w04 Er PDFHany ElGezawyNo ratings yet

- A Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards Honda Bikes in CoimbatoreDocument43 pagesA Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards Honda Bikes in Coimbatorenkputhoor62% (13)

- The Templist Scroll by :dr. Lawiy-Zodok (C) (R) TMDocument144 pagesThe Templist Scroll by :dr. Lawiy-Zodok (C) (R) TM:Lawiy-Zodok:Shamu:-El100% (5)

- Plate-Load TestDocument20 pagesPlate-Load TestSalman LakhoNo ratings yet

- Garlic Benefits - Can Garlic Lower Your Cholesterol?Document4 pagesGarlic Benefits - Can Garlic Lower Your Cholesterol?Jipson VargheseNo ratings yet

- Reiki BrochureDocument2 pagesReiki BrochureShikha AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Troubleshooting Hydraulic Circuits: Fluid PowerDocument32 pagesTroubleshooting Hydraulic Circuits: Fluid PowerMi LuanaNo ratings yet

- Interactive Architecture Adaptive WorldDocument177 pagesInteractive Architecture Adaptive Worldhoma massihaNo ratings yet

- Philippines' Legal Basis for Claims in South China SeaDocument38 pagesPhilippines' Legal Basis for Claims in South China SeaGeeNo ratings yet

- Pharmacokinetics and Drug EffectsDocument11 pagesPharmacokinetics and Drug Effectsmanilyn dacoNo ratings yet

- Hypophosphatemic Rickets: Etiology, Clinical Features and TreatmentDocument6 pagesHypophosphatemic Rickets: Etiology, Clinical Features and TreatmentDeysi Blanco CohuoNo ratings yet

- Theoretical and Actual CombustionDocument14 pagesTheoretical and Actual CombustionErma Sulistyo R100% (1)

- JK Paper Q4FY11 Earnings Call TranscriptDocument10 pagesJK Paper Q4FY11 Earnings Call TranscriptkallllllooooNo ratings yet

- Sap ThufingteDocument10 pagesSap ThufingtehangsinfNo ratings yet

- Virchow TriadDocument6 pagesVirchow Triadarif 2006No ratings yet

- An Online ECG QRS Detection TechniqueDocument6 pagesAn Online ECG QRS Detection TechniqueIDESNo ratings yet

- Xii Neet Chemistry Mcqs PDFDocument30 pagesXii Neet Chemistry Mcqs PDFMarcus Rashford100% (3)

- Accomplishment Report Yes-O NDCMC 2013Document9 pagesAccomplishment Report Yes-O NDCMC 2013Jerro Dumaya CatipayNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 AP GP PDFDocument3 pagesChapter 10 AP GP PDFGeorge ChooNo ratings yet

- Aircraft Design Project 2Document80 pagesAircraft Design Project 2Technology Informer90% (21)

- Background of The Study Statement of ObjectivesDocument4 pagesBackground of The Study Statement of ObjectivesEudelyn MelchorNo ratings yet

- ADDRESSABLE 51.HI 60854 G Contoller GuideDocument76 pagesADDRESSABLE 51.HI 60854 G Contoller Guidemohinfo88No ratings yet

- Ro-Buh-Qpl: Express WorldwideDocument3 pagesRo-Buh-Qpl: Express WorldwideverschelderNo ratings yet

- Update On The Management of Acute Pancreatitis.52Document7 pagesUpdate On The Management of Acute Pancreatitis.52Sebastian DeMarinoNo ratings yet

- 7890 Parts-Guide APDocument4 pages7890 Parts-Guide APZia HaqNo ratings yet