Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Wills 2

Uploaded by

Luke Concepcion-ButayOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Wills 2

Uploaded by

Luke Concepcion-ButayCopyright:

Available Formats

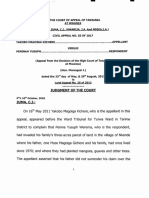

Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila EN BANC G.R. No.

1439 March 19, 1904

ANTONIO CASTAEDA, plaintiff-appellee, vs. JOSE E. ALEMANY, defendant-appellant. Ledesma, Sumulong and Quintos for appellant. The court erred in holding that all legal formalities had been complied with in the execution of the will of Doa Juana Moreno, as the proof shows that the said will was not written in the presence of under the express direction of the testratrix as required by section 618 of the Code of Civil Procedure. Antonio V. Herrero for appellee. The grounds upon which a will may be disallowed are limited to those mentioned in section 634 of the Code of Civil Procedure. WILLARD, J.: (1) The evidence in this case shows to our satisfaction that the will of Doa Juana Moreno was duly signed by herself in the presence of three witnesses, who signed it as witnesses in the presence of the testratrix and of each other. It was therefore executed in conformity with law. There is nothing in the language of section 618 of the Code of Civil Procedure which supports the claim of the appellants that the will must be written by the testator himself or by someone else in his presence and under his express direction. That section requires (1) that the will be in writing and (2) either that the testator sign it himself or, if he does sign it, that it be signed by some one in his presence and by his express direction. Who does the mechanical work of writing the will is a matter of indifference. The fact, therefore, that in this case the will was typewritten in the office of the lawyer for the testratrix is of no consequence. The English text of section 618 is very plain. The mistakes in translation found in the first Spanish edition of the code have been corrected in the second. (2) To establish conclusively as against everyone, and once for all, the facts that a will was executed with the formalities required by law and that the testator was in a condition to make a will, is the only purpose of the proceedings under the new code for the probate of a will. (Sec. 625.) The judgment in such proceedings determines and can determine nothing more. In them the court has no power to pass upon the validity of any provisions made in the will. It can not decide, for example, that a certain legacy is void and another one valid. It could not in this case make any decision upon the question whether the testratrix had the power to appoint by will a guardian for the property of her children by her first husband, or whether the person so appointed was or was not a suitable person to discharge such trust. All such questions must be decided in some other proceeding. The grounds on which a will may be disallowed are stated the section 634. Unless one of those grounds appears the will must be allowed. They all have to do with the personal condition of the testator at the time of its execution and the formalities connected therewith. It follows that neither this court nor the court below has any jurisdiction in his proceedings to pass upon the questions raised by the appellants by the assignment of error relating to the appointment of a guardian for the children of the deceased.

It is claimed by the appellants that there was no testimony in the court below to show that the will executed by the deceased was the same will presented to the court and concerning which this hearing was had. It is true that the evidence does not show that the document in court was presented to the witnesses and identified by them, as should have been done. But we think that we are justified in saying that it was assumed by all the parties during the trial in the court below that the will about which the witnesses were testifying was the document then in court. No suggestion of any kind was then made by the counsel for the appellants that it was not the same instrument. In the last question put to the witness Gonzales the phrase "this will" is used by the counsel for the appellants. In their argument in that court, found on page 15 of the record, they treat the testimony of the witnesses as referring to the will probate they were then opposing. The judgment of the court below is affirmed, eliminating therefrom, however, the clause "el cual debera ejecutarse fiel y exactamente en todas sus partes." The costs of this instance will be charged against the appellants. Arellano, C. J., Torres, Cooper, Mapa, McDonough and Johnson, JJ., concur.

Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila EN BANC G.R. No. 45629 September 22, 1938

ANTILANO G. MERCADO, petitioner, vs. ALFONSO SANTOS, Judge of First Instance of Pampanga, respondents. ROSARIO BASA DE LEON, ET AL., intervenors. Claro M. Recto and Benigno S. Aquino for petitioner. Esperanza de la Cruz and Heracio Abistao for respondents. Sotto and Sotto for intervenors. LAUREL, J.: On May 28, 1931, the petitioner herein filed in the Court of First Instance of Pampanga a petition for the probate of the will of his deceased wife, Ines Basa. Without any opposition, and upon the testimony of Benigno F. Gabino, one of the attesting witnesses, the probate court, on June 27,1931, admitted the will to probate. Almost three years later, on April 11, 1934, the five intervenors herein moved ex parte to reopen the proceedings, alleging lack of jurisdiction of the court to probate the will and to close the proceedings. Because filed ex parte, the motion was denied. The same motion was filed a second time, but with notice to the adverse party. The motion was nevertheless denied by the probate court on May 24, 1934. On appeal to this court, the order of denial was affirmed on July 26, 1935. (Basa vs. Mercado, 33 Off. Gaz., 2521.) It appears that on October 27, 1932, i. e., sixteen months after the probate of the will of Ines Basa, intervenor Rosario Basa de Leon filed with the justice of the peace court of San Fernando, Pampanga, a complaint against the petitioner herein, for falsification or forgery of the will probated as above indicated. The petitioner was arrested. He put up a bond in the sum of P4,000 and engaged the services of an attorney to undertake his defense. Preliminary investigation of the case was continued twice upon petition of the complainant. The complaint was finally dismissed, at the instance of the complainant herself, in an order dated December 8, 1932. Three months later, or on March 2, 1933, the

same intervenor charged the petitioner for the second time with the same offense, presenting the complaint this time in the justice of the peace court of Mexico, Pampanga. The petitioner was again arrested, again put up a bond in the sum of P4,000, and engaged the services of counsel to defend him. This second complaint, after investigation, was also dismissed, again at the instance of the complainant herself who alleged that the petitioner was in poor health. That was on April 27, 1933. Some nine months later, on February 2, 1934, to be exact, the same intervenor accused the same petitioner for the third time of the same offense. The information was filed by the provincial fiscal of Pampanga in the justice of the peace court of Mexico. The petitioner was again arrested, again put up a bond of P4,000, and engaged the services of defense counsel. The case was dismissed on April 24, 1934, after due investigation, on the ground that the will alleged to have been falsified had already been probated and there was no evidence that the petitioner had forged the signature of the testatrix appearing thereon, but that, on the contrary, the evidence satisfactorily established the authenticity of the signature aforesaid. Dissatisfied with the result, the provincial fiscal, on May 9, 1934, moved in the Court of First Instance of Pampanga for reinvestigation of the case. The motion was granted on May 23, 1934, and, for the fourth time, the petitioner was arrested, filed a bond and engaged the services of counsel to handle his defense. The reinvestigation dragged on for almost a year until February 18, 1934, when the Court of First Instance ordered that the case be tried on the merits. The petitioner interposed a demurrer on November 25, 1935, on the ground that the will alleged to have been forged had already been probated. This demurrer was overruled on December 24, 1935, whereupon an exception was taken and a motion for reconsideration and notice of appeal were filed. The motion for reconsideration and the proposed appeal were denied on January 14, 1936. The case proceeded to trial, and forthwith petitioner moved to dismiss the case claiming again that the will alleged to have been forged had already been probated and, further, that the order probating the will is conclusive as to the authenticity and due execution thereof. The motion was overruled and the petitioner filed with the Court of Appeals a petition for certiorari with preliminary injunction to enjoin the trial court from further proceedings in the matter. The injunction was issued and thereafter, on June 19, 1937, the Court of Appeals denied the petition for certiorari, and dissolved the writ of preliminary injunction. Three justices dissented in a separate opinion. The case is now before this court for review on certiorari. Petitioner contends (1) that the probate of the will of his deceased wife is a bar to his criminal prosecution for the alleged forgery of the said will; and, (2) that he has been denied the constitutional right to a speedy trial. 1. Section 306 of our Code of Civil Procedure provides as to the effect of judgments. SEC. 306. Effect of judgment. The effect of a judgment or final order in an action or special proceeding before a court or judge of the Philippine Islands or of the United States, or of any State or Territory of the United States, having jurisdiction to pronounce the judgment or order, may be as follows. 1. In case of a judgment or order against a specific thing, or in respect to the probate of a will, or the administration of the estate of a deceased person, or in respect to the personal, political, or legal condition or relation of a particular person, the judgment or order is conclusive upon the title of the thing, the will or administration, or the condition or relation of the person Provided, That the probate of a will or granting of letters of administration shall only be prima facie evidence of the death of the testator or intestate. xxx xxx xxx

SEC. 625. Allowance Necessary, and Conclusive as to Execution. No will shall pass either the real or personal estate, unless it is proved and allowed in the Court of First Instance, or by appeal to the Supreme Court; and the allowance by the court of a will of real and personal estate shall be conclusive as to its due execution. (Emphasis ours.) (In Manahan vs. Manahan 58 Phil., 448, 451), we held: . . . The decree of probate is conclusive with respect to the due execution thereof and it cannot be impugned on any of the grounds authorized by law, except that of fraud, in any separate or independent action or proceeding. Sec. 625, Code of Civil Procedure; Castaeda vs. Alemany, 3 Phil., 426; Pimentel vs.Palanca, 5 Phil., 436; Sahagun vs. De Gorostiza, 7 Phil., 347; Limjuco vs. Ganara, 11 Phil., 393; Montaanovs. Suesa, 14 Phil., 676; in re Estate of Johnson, 39 Phil, 156; Riera vs. Palmaroli, 40 Phil., 105; Austria vs.Ventenilla, 21 Phil., 180; Ramirez vs. Gmur, 42 Phil., 855; and Chiong Jocsoy vs. Vano, 8 Phil., 119. In 28 R. C. L., p. 377, section 378, it is said. The probate of a will by the probate court having jurisdiction thereof is usually considered as conclusive as to its due execution and validity, and is also conclusive that the testator was of sound and disposing mind at the time when he executed the will, and was not acting under duress, menace, fraud, or undue influence,and that the will is genuine and not a forgery. (Emphasis ours.) As our law on wills, particularly section 625 of our Code of Civil Procedure aforequoted, was taken almost bodily from the Statutes of Vermont, the decisions of the Supreme Court of the State relative to the effect of the probate of a will are of persuasive authority in this jurisdiction. The Vermont statute as to the conclusiveness of the due execution of a probated will reads as follows. SEC. 2356. No will shall pass either real or personal estate, unless it is proved and allowed in the probate court, or by appeal in the county or supreme court; and the probate of a will of real or personal estate shall be conclusive as to its due execution. (Vermont Statutes, p. 451.) Said the Supreme Court of Vermont in the case of Missionary Society vs. Eells (68 Vt., 497, 504): "The probate of a will by the probate court having jurisdiction thereof, upon the due notice, is conclusive as to its due execution against the whole world. (Vt. St., sec. 2336; Fosters Exrs. vs. Dickerson, 64 Vt., 233.)" The probate of a will in this jurisdiction is a proceeding in rem. The provision of notice by Publication as a prerequisite to the allowance of a will is constructive notice to the whole world, and when probate is granted, the judgment of the court is binding upon everybody, even against the State. This court held in the case of Manalo vs. Paredes and Philippine Food Co. (47 Phil., 938): The proceeding for the probate of a will is one in rem (40 Cyc., 1265), and the court acquires jurisdiction over all the persons interested, through the publication of the notice prescribed by section 630 of the Code of Civil Procedure, and any order that may be entered therein is binding against all of them. Through the publication of the petition for the probate of the will, the court acquires jurisdiction over all such persons as are interested in said will; and any judgment that may be rendered after said proceeding is binding against the whole world.

(Emphasis ours.) Section 625 of the same Code is more explicit as to the conclusiveness of the due execution of a probate will. It says.

In Everrett vs. Wing (103 Vt., 488, 492), the Supreme Court of Vermont held. In this State the probate of a will is a proceeding in rem being in form and substance upon the will itself to determine its validity. The judgment determines the status of the instrument, whether it is or is not the will of the testator. When the proper steps required by law have been taken the judgment is binding upon everybody, and makes the instrument as to all the world just what the judgment declares it to be. (Woodruff vs. Taylor, 20 Vt., 65, 73; Burbeck vs. Little, 50 Vt., 713, 715; Missionary Society vs. Eells, 68 Vt., 497, 504; 35 Atl., 463.) The proceedings before the probate court are statutory and are not governed by common law rules as to parties or causes of action. (Holdrige vs. Holdriges Estate, 53 Vt., 546, 550; Purdy vs. Estate of Purdy, 67 Vt. 50, 55; 30 Atl., 695.) No process is issued against anyone in such proceedings, but all persons interested in determining the state or conditions of the instrument are constructively notified by the publication of notice as required by G. L. 3219. (Woodruff vs. Taylor, supra; In re Warners Estate 98 Vt., 254; 271; 127 Atl., 362.) Section 333, paragraph 4, of the Code of Civil Procedure establishes an incontrovertible presumption in favor of judgments declared by it to be conclusive. SEC. 333. Conclusive Presumptions. The following presumptions or deductions, which the law expressly directs to be made from particular facts, are deemed conclusive. xxx xxx xxx

It was the case of Rex vs. Buttery, supra, which induced the Supreme Court of Massachussetts in the case of Waters vs. Stickney (12 Allen 1; 90 Am. Dec., 122) also cited by the majority opinion, to hold that "according to later and sounder decisions, the probate, though conclusive until set aside of the disposition of the property, does not protect the forger from punishment." This was reproduced in 28 R.C.L., p. 376, and quoted in Barry vs. Walker (103 Fla., 533; 137 So., 711, 715), and Thompson vs. Freeman (149 So., 740, 742), also cited in support of the majority opinion of the Court of Appeals. The dissenting opinion of the Court of Appeals in the instant case under review makes a cursory study of the statutes obtaining in England, Massachussetts and Florida, and comes to the conclusion that the decisions cited in the majority opinion do not appear to "have been promulgated in the face of statutes similar to ours." The dissenting opinion cites Whartons Criminal Evidence (11th ed., sec. 831), to show that the probate of a will in England is only prima facie proof of the validity of the will (Op. Cit. quoting Marriot vs.Marriot, 93 English Reprint, 770); and 21 L.R.A. (pp. 686689 and note), to show that in Massachussetts there is no statute making the probate of a will conclusive, and that in Florida the statute(sec. 1810, Revised Statutes) makes the probate conclusive evidence as to the validity of the will with regard to personal, and prima facie as to real estate. The cases decided by the Supreme Court of Florida cited by the majority opinion, supra, refer to wills of both personal and real estate. The petitioner cites the case of State vs. McGlynn (20 Cal., 233, decided in 1862), in which Justice Norton of the Supreme Court of California, makes the following review of the nature of probate proceedings in England with respect to wills personal and real property. In England, the probate of wills of personal estate belongs to the Ecclesiastical Courts. No probate of a will relating to real estate is there necessary. The real estate, upon the death of the party seized, passes immediately to the devisee under the will if there be one; or if there be no will, to the heir at law. The person who thus becomes entitled takes possession. If one person claims to be the owner under a will, and another denies the validity of the will and claims to be the owner as heir at law, an action of ejectment is brought against the party who may be in possession by the adverse claimant; and on the trial of such an action, the validity of the will is contested, and evidence may be given by the respective parties as to the capacity of the testator to make a will, or as to any fraud practiced upon him, or as to the actual execution of it, or as to any other circumstance affecting its character as a valid devise of the real estate in dispute. The decision upon the validity of the will in such action becomes res adjudicata, and is binding and conclusive upon the parties to that action and upon any person who may subsequently acquire the title from either of those parties; but the decision has no effect upon other parties, and does not settle what may be called the status or character of the will, leaving it subject to be enforced as a valid will, or defeated as invalid, whenever other parties may have a contest depending upon it. A probate of a will of personal property, on the contrary, is a judicial determination of the character of the will itself. It does not necessarily or ordinarily arise from any controversy between adverse claimants, but is necessary in order to authorize a disposition of the personal estate in pursuance of its provisions. In case of any controversy between adverse claimants of the personal estate, the probate is given in evidence and is binding upon the parties, who are not at liberty to introduce any other evidence as to the validity of the will. The intervenors, on the other hand, attempt to show that the English law on wills is different from that stated in the case of State vs. McGlynn, supra, citing the following statutes. 1. The Wills Act, 1837 (7 Will. 4 E 1 Vict. c. 26). 2. The Court of Probate Act, 1857 (20 and 21 Vict. c. 77).

4. The judgment or order of a court, when declared by this code to be conclusive. Conclusive presumptions are inferences which the law makes so peremptory that it will not allow them to be overturned by any contrary proof however strong. (Brant vs. Morning Journal Assn., 80 N.Y.S., 1002, 1004; 81 App. Div., 183; see, also, Joslyn vs. Puloer, 59 Hun., 129, 140, 13 N.Y.S., 311.) The will in question having been probated by a competent court, the law will not admit any proof to overthrow the legal presumption that it is genuine and not a forgery. The majority decision of the Court of Appeals cites English decisions to bolster up its conclusion that "the judgment admitting the will to probate is binding upon the whole world as to the due execution and genuineness of the will insofar as civil rights and liabilities are concerned, but not for the purpose of punishment of a crime." The cases of Dominus Rex vs. Vincent, 93 English Reports, Full Reprint, 795, the first case being decided in 1721, were cited to illustrate the earlier English decisions to the effect that upon indictment for forging a will, the probating of the same is conclusive evidence in the defendants favor of its genuine character. Reference is made, however, to the cases of Rex vs. Gibson, 168 English Reports, Full Reprint, 836, footnote (a), decided in 1802, and Rex vs. Buttery and Macnamarra, 168 English Reports, Full Reprint, 836, decided in 1818, which establish a contrary rule. Citing these later cases, we find the following quotation from Black on Judgments, Vol. II, page 764. A judgment admitting a will to probate cannot be attacked collaterally although the will was forged; and a payment to the executor named therein of a debt due the decedent will discharge the same, notwithstanding the spurious character of the instrument probated. It has also been held that, upon an indictment for forging a will, the probate of the paper in question is conclusive evidence in the defendants favor of its genuine character. But this particular point has lately been ruled otherwise.

3. The Judicature Act, 1873 (36 and 37 Vict. c. 66). The Wills Act of 1837 provides that probate may be granted of "every instrumental purporting to be testamentary and executed in accordance with the statutory requirements . . . if it disposes of property, whether personal or real." The Ecclesiastical Courts which took charge of testamentary causes (Ewells Blackstone [1910], p. 460), were determined by the Court of Probate Act of 1857, and the Court of Probate in turn was, together with other courts, incorporated into the Supreme Court of Judicature, and transformed into the Probate Division thereof, by the Judicature Act of 1873. (Lord Halsbury, The Laws of England[1910], pp. 151156.) The intervenors overlook the fact, however, that the case of Rex vs. Buttery and Macnamarra, supra, upon which they rely in support of their theory that the probate of a forged will does not protect the forger from punishment, was decided long before the foregoing amendatory statutes to the English law on wills were enacted. The case of State vs. McGlynn may be considered, therefore, as more or less authoritative on the law of England at the time of the promulgation of the decision in the case of Rex vs. Buttery and Macnamarra. In the case of State vs. McGlynn, the Attorney General of California filed an information to set aside the probate of the will of one Broderick, after the lapse of one year provided by the law of California for the review of an order probating a will, in order that the estate may be escheated to the State of California for the review of an probated will was forged and that Broderick therefore died intestate, leaving no heirs, representatives or devisees capable of inheriting his estate. Upon these facts, the Supreme Court of California held. The fact that a will purporting to be genuine will of Broderick, devising his estate to a devisee capable of inheriting and holding it, has been admitted to probate and established as a genuine will by the decree of a Probate Court having jurisdiction of the case, renders it necessary to decide whether that decree, and the will established by it, or either of them, can be set aside and vacated by the judgment of any other court. If it shall be found that the decree of the Probate Court, not reversed by the appellate court, is final and conclusive, and not liable to be vacated or questioned by any other court, either incidentally or by any direct proceeding, for the purpose of impeaching it, and that so long as the probate stands the will must be recognized and admitted in all courts to be valid, then it will be immaterial and useless to inquire whether the will in question was in fact genuine or forged. (State vs. McGlynn, 20 Cal., 233; 81 Am. Dec., 118, 121.). Although in the foregoing case the information filed by the State was to set aside the decree of probate on the ground that the will was forged, we see no difference in principle between that case and the case at bar. A subtle distinction could perhaps be drawn between setting aside a decree of probate, and declaring a probated will to be a forgery. It is clear, however, that a duly probated will cannot be declared to be a forgery without disturbing in a way the decree allowing said will to probate. It is at least anomalous that a will should be regarded as genuine for one purpose and spurious for another. The American and English cases show a conflict of authorities on the question as to whether or not the probate of a will bars criminal prosecution of the alleged forger of the probate will. We have examined some important cases and have come to the conclusion that no fixed standard maybe adopted or drawn therefrom, in view of the conflict no less than of diversity of statutory provisions obtaining in different jurisdictions. It behooves us, therefore, as the court of last resort, to choose that rule most consistent with our statutory law, having in view the needed stability of property rights and the public interest in general. To be sure, we have seriously reflected upon the dangers of evasion from punishment of culprits deserving of the severity of the law in cases where, as here, forgery is discovered after the probate of the will and the prosecution is had before the prescription of the offense. By and large, however, the balance seems inclined in favor of the view that we have taken. Not only does the law surround the execution of the will with the

necessary formalities and require probate to be made after an elaborate judicial proceeding, but section 113, not to speak of section 513, of our Code of Civil Procedure provides for an adequate remedy to any party who might have been adversely affected by the probate of a forged will, much in the same way as other parties against whom a judgment is rendered under the same or similar circumstances. (Pecson vs.Coronel, 43 Phil., 358.)The aggrieved party may file an application for relief with the proper court within a reasonable time, but in no case exceeding six months after said court has rendered the judgment of probate, on the ground of mistake, inadvertence, surprise or excusable neglect. An appeal lies to review the action of a court of first instance when that court refuses to grant relief. (Banco Espaol Filipino vs. Palanca, 37 Phil., 921; Philippine Manufacturing Co. vs. Imperial, 47 Phil., 810; Samia vs. Medina, 56 Phil., 613.) After a judgment allowing a will to be probated has become final and unappealable, and after the period fixed by section 113 of the Code of Civil Procedure has expired, the law as an expression of the legislative wisdom goes no further and the case ends there. . . . The court of chancery has no capacity, as the authorities have settled, to judge or decide whether a will is or is not a forgery; and hence there would be an incongruity in its assuming to set aside a probate decree establishing a will, on the ground that the decree was procured by fraud, when it can only arrive at the fact of such fraud by first deciding that the will was a forgery. There seems, therefore, to be a substantial reason, so long as a court of chancery is not allowed to judge of the validity of a will, except as shown by the probate, for the exception of probate decrees from the jurisdiction which courts of chancery exercise in setting aside other judgments obtained by fraud. But whether the exception be founded in good reason or otherwise, it has become too firmly established to be disregarded. At the present day, it would not be a greater assumption to deny the general rule that courts of chancery may set aside judgments procured by fraud, than to deny the exception to that rule in the case of probate decrees. We must acquiesce in the principle established by the authorities, if we are unable to approve of the reason. Judge Story was a staunch advocate for the most enlarged jurisdiction of courts of chancery, and was compelled to yield to the weight of authority. He says "No other excepted case is known to exist; and it is not easy to discover the grounds upon which this exception stands, in point of reason or principle, although it is clearly settled by authority. (1 Storys Eq. Jur. sec. 440.)" (State vs. McGlynn, 20 Cal., 233; 81 Am. Dec., 118, 129. See, also, Tracy vs. Muir, 121 American State Reports, 118, 125.) We hold, therefore, that in view of the provisions of sections 306, 333 and 625 of our Code of Civil Procedure, criminal action will not lie in this jurisdiction against the forger of a will which had been duly admitted to probate by a court of competent jurisdiction. The resolution of the foregoing legal question is sufficient to dispose of the case. However, the other legal question with reference to the denial to the accused of his right to a speedy trial having been squarely raised and submitted, we shall proceed to consider the same in the light of cases already adjudicated by this court. 2. The Constitution of the Philippines provides that "In all criminal prosecutions the accused . . . shall enjoy the right . . . to have a speedy . . . trial. . . . (Art. III, sec. 1, par. 17. See, also, G.O. No. 58, sec. 15, No. 7.) Similar provisions are to be found in the Presidents Instructions to the Second Philippine Commission (par. 11), the Philippine Bill of July 1, 1902 (sec. 5, par. 2) and the Jones Act of August 29, 1916 (sec. 3, par. 2). The provisions in the foregoing organic acts appear to have been taken from similar provisions in the Constitution of the United States (6th Amendment) and those of the various states of the American Union. A similar injunction is contained in the Malolos Constitution (art. 8, Title IV), not to speak of other constitutions. More than once this court had occasion to set aside the proceedings in criminal cases to give effect to the constitutional injunction of speedy trial. (Conde vs. Judge of First

Instance and Fiscal of Tayabas [1923], 45 Phil., 173; Conde vs. Rivera and Unson[1924], 45 Phil., 650; People vs. Castaeda and Fernandez[1936]), 35 Off. Gaz., 1269; Kalaw vs. Apostol, Oct. 15, 1937, G.R. No. 45591; Esguerra vs. De la Costa, Aug. 30,1938, G.R. No. 46039.). In Conde vs. Rivera and Unson, supra, decided before the adoption of our Constitution, we said. Philippine organic and statutory law expressly guarantee that in all criminal prosecutions the accused shall enjoy the right to have a speedy trial. Aurelia Conde, like all other accused persons, has a right to a speedy trial in order that if innocent she may go free, and she has been deprived of that right in defiance of law. Dismissed from her humble position, and compelled to dance attendance on courts while investigations and trials are arbitrarily postponed without her consent, is palpably and openly unjust to her and a detriment to the public. By the use of reasonable diligence, the prosecution could have settled upon the appropriate information, could have attended to the formal preliminary examination, and could have prepared the case for a trial free from vexatious, capricious, and oppressive delays. In People vs. Castaeda and Fernandez, supra , this court found that the accused had not been given a fair and impartial trial. The case was to have been remanded to the court a quo for a new trial before an impartial judge. This step, however, was found unnecessary. A review of the evidence convinced this court that a judgment of conviction for theft, as charged, could not be sustained and, having in view the right to a speedy trial guaranteed by the Constitution to every person accused of crime, entered a judgment acquitting the accused, with costs de oficio. We said. . . . The Constitution, Article III, section 1, paragraph 17, guarantees to every accused person the right to a speedy trial. This criminal proceeding has been dragging on for almost five years now. The accused have twice appealed to this court for redress from the wrong that they have suffered at the hands of the trial court. At least one of them, namely Pedro Fernandez alias Piro, had been con-fined in prison from July 20, 1932 to November 27, 1934, for inability to post the required bond of P3,000 which was finally reduced to P300. The Government should be the last to set an example of delay and oppression in the administration of justice and it is the moral and legal obligation of this court to see that the criminal proceedings against the accused come to an end and that they be immediately dis-charged from the custody of the law. (Conde vs.Rivera and Unson, 45 Phil., 651.) In Kalaw vs. Apostol, supra, the petitioner invoked and this court applied and gave effect to the doctrines stated in the second Conde case, supra. In granting the writs prayed for, this court, after referring to the constitutional and statutory provisions guaranteeing to persons accused of crime the right to a speedy trial, said: Se infiere de los preceptos legales transcritos que todo acusado en causa criminal tiene derecho a ser juzgado pronta y publicamente. Juicio rapido significa un juicioque se celebra de acuerdo con la ley de procedimiento criminal y los reglamentos, libre de dilaciones vejatorias, caprichosas y opersivas (Burnett vs.State, 76 Ark., 295; 88S. W., 956; 113 AMSR, 94; Stewart vs. State, 13 Ark., 720; Peo. vs. Shufelt, 61 Mich., 237; 28 N. W., 79; Nixon vs. State, 10 Miss., 497; 41 AMD., 601; State vs. Cole, 4 Okl. Cr., 25; 109 P., 736; State vs. Caruthers, 1 Okl. Cr., 428; 98 P., 474; State vs. Keefe, 17 Wyo., 227, 98 p., 122;22 IRANS, 896; 17 Ann. Cas., 161). Segun los hechos admitidos resulta que al recurrente se le concedio vista parcial del asunto, en el Juzgado de Primera Instancia de Samar, solo despues de haber transcurrido ya mas de un ao y medio desde la presentacion de la primera querella y desde la recepcion de la causa en dicho Juzgado, y despues

de haberse transferido dos veces la vista delasunto sin su consentimiento. A esto debe aadirse que laprimera transferencia de vista era claramente injustificadaporque el motivo que se alego consistio unicamente en laconveniencia personal del ofendido y su abogado, no habiendose probado suficientemente la alegacion del primero de quese hallaba enfermo. Es cierto que el recurrente habia pedido que, en vez de sealarse a vista el asunto para el mayo de 1936, lo fuera para el noviembre del mismo ao; pero,aparte de que la razon que alego era bastante fuerte porquesu abogado se oponia a comparecer por compromisos urgentes contraidos con anterioridad y en tal circunstancia hubiera quedado indefenso si hubiese sido obligado a entraren juicio, aparece que la vista se pospuso por el Juzgado amotu proprio, por haber cancelado todo el calendario judicial preparado por el Escribano para el mes de junio. Declaramos, con visto de estos hechos, que al recurrents se leprivo de su derecho fundamental de ser juzgado prontamente. Esguerra vs. De la Costa, supra, was a petition for mandamus to compel the respondent judge of the Court of First Instance of Rizal to dismiss the complaint filed in a criminal case against the petitioner, to cancel the bond put up by the said petitioner and to declare the costs de oficio. In accepting the contention that the petitioner had been denied speedy trial, this court said: Consta que en menos de un ao el recurrente fue procesado criminalmente por el alegado delito de abusos deshonestos, en el Juzgado de Paz del Municipio de Cainta, Rizal. Como consecuencia de las denuncias que contra el se presentaron fue arrestado tres veces y para gozar de libertad provisional, en espera de los juicios, se vio obligado a prestartres fianzas por la suma de P1,000 cada una. Si no se da fin al proceso que ultimamente se ha incoado contra el recurrente la incertidumbre continuara cerniendose sobre el y las consiguientes molestias y preocupaciones continuaran igualmente abrumandole. El Titulo III, articulo 1, No. 17,de la Constitucion preceptua que en todo proceso criminalel acusado tiene derecho de ser juzgado pronta y publicamente. El Articulo 15, No. 7, de la Orden General No. 58 dispone asimismo que en las causas criminales el acusado tendra derecho a ser juzgado pronta y publicamente. Si el recurrente era realmente culpable del delito que se le imputo, tenia de todos modos derechos a que fuera juzgado pronta y publicamente y sin dilaciones arbitrarias y vejatorias. Hemos declarado reiteradamente que existe un remedio positivo para los casos en que se viola el derecho constitucional del acusado de ser juzgado prontamente. El acusado que esprivado de su derecho fundomental de ser enjuiciado rapidamente tiene derecho a pedir que se le ponga en libertad, si estuviese detenido, o a que la causa que pende contra el sea sobreseida definitivamente. (Conde contra Rivera y Unson, 45 Jur. Fil., 682; In the matter of Ford [1911], 160 Cal., 334; U. S. vs. Fox [1880], 3 Mont., 512; Kalaw contra Apostol, R. G. No. 45591, Oct. 15, 1937; Pueblo contra Castaeda y Fernandez, 35 Gac. Of., 1357.) We are again called upon to vindicate the fundamental right to a speedy trial. The facts of the present case may be at variance with those of the cases hereinabove referred to. Nevertheless, we are of the opinion that, under the circumstances, we should consider the substance of the right instead of indulging in more or less academic or undue factual differentiations. The petitioner herein has been arrested four times, has put up a bond in the sum of P4,000 and has engaged the services of counsel to undertake his defense an equal number of times. The first arrest was made upon a complaint filed by one of the intervenors herein for alleged falsification of a will which, sixteen months before, had been probated in court. This complaint, after investigation, was dismissed at the complainant's own request. The second arrest was made upon a complaint charging the same offense and this complaint, too, was dismissed at the behest of the complainant herself who alleged the quite startling ground that the petitioner was in poor health. The third arrest

was made following the filing of an information by the provincial fiscal of Pampanga, which information was dismissed, after due investigation, because of insufficiency of the evidence. The fourth arrest was made when the provincial fiscal secured a reinvestigation of the case against the petitioner on the pretext that he had additional evidence to present, although such evidence does not appear to have ever been presented. It is true that the provincial fiscal did not intervene in the case until February 2, 1934, when he presented an information charging the petitioner, for the third time, of the offense of falsification. This, however, does not matter. The prosecution of offenses is a matter of public interest and it is the duty of the government or those acting in its behalf to prosecute all cases to their termination without oppressive, capricious and vexatious delay. The Constitution does not say that the right to a speedy trial may be availed of only where the prosecution for crime is commenced and undertaken by the fiscal. It does not exclude from its operation cases commenced by private individuals. Where once a person is prosecuted criminally, he is entitled to a speedy trial, irrespective of the nature of the offense or the manner in which it is authorized to be commenced. In any event, even the actuations of the fiscal himself in this case is not entirely free from criticism. From October 27, 1932, when the first complaint was filed in the justice of the peace court of San Fernando, to February 2, 1934, when the provincial fiscal filed his information with the justice of the peace of Mexico, one year, three months and six days transpired; and from April 27, 1933, when the second criminal complaint was dismissed by the justice of the peace of Mexico, to February 2, 1934, nine months and six days elapsed. The investigation following the fourth arrest, made after the fiscal had secured a reinvestigation of the case, appears also to have dragged on for about a year. There obviously has been a delay, and considering the antecedent facts and circumstances within the knowledge of the fiscal, the delay may not at all be regarded as permissible. In Kalaw vs. Apostol, supra, we observed that the prosecuting officer all prosecutions for public offenses (secs. 1681 and 2465 of the Rev. Adm. Code), and that it is his duty to see that criminal cases are heard without vexatious, capricious and oppressive delays so that the courts of justice may dispose of them on the merits and determine whether the accused is guilty or not. This is as clear an admonition as could be made. An accused person is entitled to a trial at the earliest opportunity. (Sutherland on the Constitution, p. 664; United States vs. Fox, 3 Mont., 512.) He cannot be oppressed by delaying he commencement of trial for an unreasonable length of time. If the proceedings pending trial are deferred, the trial itself is necessarily delayed. It is not to be supposed, of course, that the Constitution intends to remove from the prosecution every reasonable opportunity to prepare for trial. Impossibilities cannot be expected or extraordinary efforts required on the part of the prosecutor or the court. As stated by the Supreme Court of the United States, "The right of a speedy trial is necessarily relative. It is consistent with delays and depends upon circumstances. It secures rights to a defendant. It does not preclude the rights of public justice." (Beavers vs. Haubert [1905], 198 U. S., 86; 25 S. Ct., 573; 49 Law. ed., 950, 954.). It may be true, as seems admitted by counsel for the intervenors, in paragraph 8, page 3 of his brief, that the delay was due to "the efforts towards reaching an amicable extrajudicial compromise," but this fact, we think, casts doubt instead upon the motive which led the intervenors to bring criminal action against the petitioner. The petitioner claims that the intention of the intervenors was to press upon settlement, with the continuous threat of criminal prosecution, notwithstanding the probate of the will alleged to have been falsified. Argument of counsel for the petitioner in this regard is not without justification. Thus after the filing of the second complaint with the justice of the peace court of Mexico, complainant herself, as we have seen, asked for dismissal of the complaint, on the ground that "el acusado tenia la salud bastante delicada," and, apparently because of failure to arrive at any settlement, she decided to renew her complaint. Counsel for the intervenors contend and the contention is sustained by the Court of Appeals that the petitioner did not complain heretofore of the denial of his constitutional right to a speedy trial. This is a mistake. When the petitioner, for the fourth time, was ordered arrested by the Court of First Instance of Pampanga, he moved for reconsideration of the

order of arrest, alleging, among other things, "Que por estas continuas acusaciones e investigaciones, el acusado compareciente no obstante su mal estado de salud desde el ao 1932 en que tuvo que ser operado por padecer de tuberculosis ha tenido que sostener litigios y ha sufrido la mar de humiliaciones y zozobras y ha incudo en enormes gastos y molestias y ha desatendido su quebrantada salud." The foregoing allegation was inserted on page 6 of the amended petition for certiorari presented to the Court of Appeals. The constitutional issue also appears to have been actually raised and considered in the Court of Appeals. In the majority opinion of that court, it is stated: Upon the foregoing facts, counsel for the petitioner submits for the consideration of this court the following questions of law: First, that the respondent court acted arbitrarily and with abuse of its authority, with serious damage and prejudice to the rights and interests of the petitioner, in allowing that the latter be prosecuted and arrested for the fourth time, and that he be subjected, also for the fourth time, to a preliminary investigation for the same offense, hereby converting the court into an instrument of oppression and vengeance on the part of the alleged offended parties, Rosario Basa et al.; . . . . And in the dissenting opinion, we find the following opening paragraph: We cannot join in a decision declining to stop a prosecution that has dragged for about five years and caused the arrest on four different occasions of a law abiding citizen for the alleged offense of falsifying a will that years be competent jurisdiction. From the view we take of the instant case, the petitioner is entitled to have the criminal proceedings against him quashed. The judgment of the Court of Appeals is hereby reversed, without pronouncement regarding costs. So ordered. Avancea, C.J., Villa-Real, Imperial, Diaz and Concepcion, JJ., concur.

Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila EN BANC G.R. No. L-6620 January 11, 1912

ALEJANDRA AUSTRIA, petitioner-appellee, vs. RAMON VENTENILLA, ET AL., opponents-appellants. Addison B. Ritchey, for appellants. Pedro Ma. Sison, for appellee. JOHNSON, J.: It appears from the record that one Antonio Ventenilla, died on the 13th of March, 1909, in the municipality of Mangatarem, Province of Pangasinan, leaving a will which, after due notice in accordance with the provisions of the law, was duly admitted to probate on the 14th of April, 1909, and the said Doa Alejandra Austria was appointed administratrix of his estate, by order of the Honorable James C. Jenkins, judge of the Court of First Instance of the Province of Pangasinan. On the 30th day of July, 1909, the said administratrix (Doa Alejandra Austria) with will annexed, presented a report of her administration of said estate, petitioned the court, after due notification to all of the parties interested, to distribute the estate in accordance with the will and the law.

So far as the record show no action was taken upon said petition until the 5th day of October, 1910. On the 6th day of August, 1910, the said opponents, through their attorney, A. B. Ritchey, presented the following petition, asking that the will of the said Antonio Ventenilla be annulled: PETITION FOR ANNULMENT OF A WILL. Now come Don Ramon Ventenilla, Eulalio Soriano V., Domingo Soriano, Carmen Rosario, Maria Ventenilla, and Oliva Dizon to impugn the instrument to this court, said to be the last will and testament of the said deceased, on the following grounds: That before his death the deceased always intended to distribute his property in equal shares among his wife and his brothers and their representatives, and often expressed such intention before executing the instrument herein submitted, and after executing it often declared that he had distributed the same in the manner and aforesaid; That the deceased could not read or write Spanish and that therefore on the date of executing said instrument he did not know what the same contained except through translation; That the said instrument was not translated to the testator, or if so, it was not correctly translated, and that said deceased never intended to execute it as his last will and testament in the manner and form of the instrument herein submitted, and that at the time of his death he thought that the instrument executed clearly ordered the distribution in the manner aforesaid; That by reason of the fraud and deceit practiced upon the testator and a lack of a good translation, the herein submitted is null and void; That the tenth paragraph of said instrument is null because of its obscurity and ambiguity and is in plain contradiction to the proceeding paragraphs, and that the other paragraph have more force and weight; Therefore, the petitioners pray the court: (1) That the testamentary provisions of the will of the deceased Antonio Ventenilla be declared null and void; that the inheritance of the said deceased be declared intestate; that his window and Don Hemorgenes Mendoza be appointed administrators under sufficient bond to protect the interest of the heirs and the other interest parties; (2) That the will be amended, in case the court does not see fit to annul it, by declaring the tenthparagraph null; (3) That they be further granted any other relief which appear just and equitable to the court. Lingayen, P. I., August 6, 1910. (Sgd.) A. B. Attorney for petitioners. Ritchey,

the law, until more than fifteen months had expired from the date on which the lower court duly admitted said will to probate. Section 625 of the Code of Procedure in Civil Actions provides that: No will shall either the real or personal estate unless it is proved and allowed in the Court of First Instance or by appeal to the Supreme Court; and the allowance by the court of a will of real and personal estate shall be conclusive as to its due execution. This court has held, under the provision of this section, that "the probate of a will is conclusive as to its due execution, and as to the testamentary capacity of the testator." (Castaeda vs. Alemany, 3 Phil. Rep., 426; Pimentel vs. Palanca, 5 Phil. Rep., 436; Sahagun vs. Gorostiza, 7 Phil. Rep., 347; Chiong Joc-Soy vs. Vao, 8 Phil. Rep., 119; Sanches vs. Pascual, 11 Phil. Rep., 395; Montaano vs. Suesa, 14 Phil. Rep., 676.) When no appeal is taken from an order probating a will, the heirs can not, in subsequent litigation in the same proceedings, raise question relating to its due execution. (Chong Joc-Soy vs. Vao et al., 8 Phil. Rep., 119.) The opponents not having appealed from the order admitting the will to probate, as they had a right to do, that order is final and conclusive, (Pimentel vs. Palanca, supra) unless some fraud sufficient to vitiate the proceedings is discovered. In the present case, however, the alleged fraud, in view of all the facts contained in the record, in our opinion, is not sufficiently proved to justify a reopening of the probate of the will in question, especially in view of the long delay of the parties interested. The said section 625 was evidently taken from section 2356 of the Statutes of Vermont. In most of the states of the United States certain number of months is given to the interested parties to appeal from an order of the court admitting to probate a will. (In the matter of the estate of Giovanni Sbarboro, 63 Cal., 5; Thompson vs. Samson, 64 Cal., 330; In the matter of the estate of Richard T. Maxell, 74 Cal., 387; Wetherbee et al. vs. Chase, 57 Vt., 347.) Under said section 625 and the decisions of the court, it seems that the only time given the parties who are displeased with the order admitting a will to probate, is the time given for appeals in ordinary actions. Without deciding whether or not the order admitting a will to probate can be open for fraud, after the time allowed for an appeal has expired, we hold in the present case simply that the showing as to fraud is not sufficient to justify a reopening of the proceedings. The judgment of the lower court is, therefore, hereby affirmed with costs. Torres, Mapa, Moreland and Trent, JJ., concur.

Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila EN BANC G.R. No. 38050 September 22, 1933 In the matter of the will of Donata Manahan. TIBURCIA MANAHAN, petitioner-appellee, vs. ENGRACIA MANAHAN, opponent-appellant. J. Fernando Rodrigo for appellant. Heraclio H. del Pilar for appellee. IMPERIAL, J.: This is an appeal taken by the appellant herein, Engracia Manahan, from the order of the Court of the First Instance of Bulacan dated July 1, 1932, in the matter of the will of the deceased Donata Manahan, special

It will be noted that the opponents made no effort to question the legality of he will, even though legal notice had been given in accordance with

proceedings No. 4162, denying her motion for reconsideration and new trial filed on May 11, 1932. The fact in the case are as follows: On August 29, 1930, Tiburcia Manahan instituted special proceedings No. 4162, for the probate of the will of the deceased Donata Manahan, who died in Bulacan, Province of Bulacan, on August 3, 1930. The petitioner herein, niece of the testatrix, was named the executrix in said will. The court set the date for the hearing and the necessary notice required by law was accordingly published. On the day of the hearing of the petition, no opposition thereto was filed and, after the evidence was presented, the court entered the decree admitting the will to probate as prayed for. The will was probated on September 22, 1930. The trial court appointed the herein petitioner executrix with a bond of P1,000, and likewise appointed the committed on claims and appraisal, whereupon the testamentary proceedings followed the usual course. One year and seven months later, that is, on My 11, 1932, to be exact, the appellant herein filed a motion for reconsideration and a new trial, praying that the order admitting the will to probate be vacated and the authenticated will declared null and void ab initio. The appellee herein, naturally filed her opposition to the petition and, after the corresponding hearing thereof, the trial court erred its over of denial on July 1, 1932. Engracia Manahan, under the pretext of appealing from this last order, likewise appealed from the judgment admitting the will to probate. In this instance, the appellant assigns seven (7) alleged errors as committed by the trial court. Instead of discussing them one by one, we believe that, essentially, her claim narrows down to the following: (1) That she was an interested party in the testamentary proceedings and, as such, was entitled to and should have been notified of the probate of the will; (2) that the court, in its order of September 22, 1930, did not really probate the will but limited itself to decreeing its authentication; and (3) that the will is null and void ab initio on the ground that the external formalities prescribed by the Code of Civil Procedure have not been complied with in the execution thereof. The appellant's first contention is obviously unfounded and untenable. She was not entitled to notification of the probate of the will and neither had she the right to expect it, inasmuch as she was not an interested party, not having filed an opposition to the petition for the probate thereof. Her allegation that she had the status of an heir, being the deceased's sister, did not confer on her the right to be notified on the ground that the testatrix died leaving a will in which the appellant has not been instituted heir. Furthermore, not being a forced heir, she did not acquire any successional right. The second contention is puerile. The court really decreed the authentication and probate of the will in question, which is the only pronouncement required of the trial court by the law in order that the will may be considered valid and duly executed in accordance with the law. In the phraseology of the procedural law, there is no essential difference between the authentication of a will and the probate thereof. The words authentication and probate are synonymous in this case. All the law requires is that the competent court declared that in the execution of the will the essential external formalities have been complied with and that, in view thereof, the document, as a will, is valid and effective in the eyes of the law. The last contention of the appellant may be refuted merely by stating that, once a will has been authenticated and admitted to probate, questions relative to the validity thereof can no more be raised on appeal. The decree of probate is conclusive with respect to the due execution thereof and it cannot impugned on any of the grounds authorized by law, except that of fraud, in any separate or independent action or proceedings (sec. 625, Code of Civil Procedure; Castaeda vs. Alemany, 3 Phil., 426; Pimentel vs. Palanca, 5 Phil., 436; Sahagun vs. De Gorostiza, 7 Phil., 347; Limjuco vs. Ganara, 11 Phil., 393; Montaano vs. Suesa, 14 Phil., 676; In re Estate of Johnson, 39 Phil., 156; Riera vs. Palmaroli, 40 Phil., 105; Austria vs. Ventenilla, 21 Phil., 180; Ramirez vs. Gmur, 42 Phil., 855; and Chiong Joc-Soy vs. Vao, 8 Phil., 119). But there is another reason which prevents the appellant herein from successfully maintaining the present action and it is that inasmuch as the proceedings followed in a testamentary case are in rem, the trial court's decree admitting the will to probate was effective and conclusive against her, in accordance with the provisions of section 306 of the said Code of Civil Procedure which reads as follows: SEC. 306. EFFECT OF JUDGMENT. . . . .

1. In case of a judgment or order against a specific thing, or in respect to the probate of a will, or the administration of the estate of a deceased person, or in respect to the personal, political, or legal condition or relation of a particular person the judgment or order is conclusive upon the title of the thing, the will or administration, or the condition or relation of the person: Provided, That the probate of a will or granting of letters of administration shall only be prima facie evidence of the death of the testator or intestate; . . . . On the other hand, we are at a loss to understand how it was possible for the herein appellant to appeal from the order of the trial court denying her motion for reconsideration and a new trial, which is interlocutory in character. In view of this erroneous interpretation, she succeeded in appealing indirectly from the order admitting the will to probate which was entered one year and seven months ago. Before closing, we wish to state that it is not timely to discuss herein the validity and sufficiency of the execution of the will in question. As we have already said, this question can no more be raised in this case on appeal. After due hearing, the court found that the will in question was valid and effective and the order admitting it to probate, thus promulgated, should be accepted and respected by all. The probate of the will in question now constitutes res judicata. Wherefore, the appeal taken herein is hereby dismissed, with costs against the appellant. So ordered. Avancea, C.J., Malcolm, Villa-Real, and Hull, JJ., concur.

Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila EN BANC G.R. No. L-48840 December 29, 1943 ERNESTO M. GUEVARA, petitioner-appellant, vs. ROSARIO GUEVARA and her husband PEDRO BUISON, respondent-appellees. Primacias, Abad, Mencias & Castillo for appellant. Pedro C. Quinto for appellees. OZAETA, J.: Ernesto M. Guevarra and Rosario Guevara, ligitimate son and natural daughter, respectively, of the deceased Victorino L. Guevara, are litigating here over their inheritance from the latter. The action was commenced on November 12, 1937, by Rosario Guevara to recover from Ernesto Guevara what she claims to be her strict ligitime as an acknowledged natural daughter of the deceased to wit, a portion of 423,492 square meters of a large parcel of land described in original certificate of title No. 51691 of the province of Pangasinan, issued in the name of Ernesto M. Guervara and to order the latter to pay her P6,000 plus P2,000 a year as damages for withholding such legitime from her. The defendant answered the complaint contending that whatever right or rights the plaintiff might have had, had been barred by the operation of law. It appears that on August 26, 1931, Victorino L. Guevara executed a will (exhibit A), apparently with all the formalities of the law, wherein he made the following bequests: To his stepdaughter Candida Guevara, a pair of earrings worth P150 and a gold chain worth P40; to his son Ernesto M. Guevara, a gold ring worth P180 and all the furniture, pictures, statues, and other religious objects found in the residence of the testator in Poblacion Sur, Bayambang, Pangasinan; "a mi hija Rosario Guevara," a pair of earrings worth P120; to his stepson Piuo Guevara, a ring worth P120; and to his wife by second marriage, Angustia Posadas, various pieces of jewelry worth P1,020. He also made the following devises: "A mis hijos Rosario Guevara y Ernesto M. Guevara y a mis hijastros, Vivencio, Eduviges, Dionisia, Candida y Pio, apellidados Guevara," a residential lot with its improvements situate in the town of Bayambang, Pangasinan, having an area of 960 square meters and assessed at P540; to his wife Angustia Posadas he confirmed the donation propter nuptias theretofore made by him to her of a portion of 25 hectares of the large parcel of land of 259-

odd hectares described in plan Psu-66618. He also devised to her a portion of 5 hectares of the same parcel of land by way of complete settlement of her usufructurary right.1awphil.net He set aside 100 hectares of the same parcel of land to be disposed of either by him during his lifetime or by his attorney-in-fact Ernesto M. Guevara in order to pay all his pending debts and to degray his expenses and those of his family us to the time of his death. The remainder of said parcel of land his disposed of in the following manner: (d). Toda la porcion restante de mi terreno arriba descrito, de la extension superficial aproximada de ciento veintinueve (129) hectareas setenta (70) areas, y veiticinco (25) centiares, con todas sus mejoras existentes en la misma, dejo y distribuyo, pro-indiviso, a mis siguientes herederos como sigue: A mi hijo legitimo, Ernesto M. Guevara, ciento ocho (108) hectareas, ocho (8) areas y cincuenta y cuatro (54) centiareas, hacia la parte que colinda al Oeste de las cien (100) hectareas referidas en el inciso ( a) de este parrafo del testamento, como su propiedad absoluta y exclusiva, en la cual extension superficial estan incluidas cuarenta y tres (43) hectareas, veintitres (23) areas y cuarenta y dos (42) centiareas que le doy en concepto de mejora. A mi hija natural reconocida, Rosario Guevara, veintiun (21) hectareas, sesenta y un (61) areas y setenta y un (71) centiareas, que es la parte restante. Duodecimo. Nombro por la presente como Albacea Testamentario a mi hijo Ernesto M. Guevara, con relevacion de fianza. Y una vez legalizado este testamento, y en cuanto sea posible, es mi deseo, que los herederos y legatarios aqui nombrados se repartan extrajudicialmente mis bienes de conformidad con mis disposiciones arriba consignadas. Subsequently, and on July 12, 1933, Victorino L. Guevarra executed whereby he conveyed to him the southern half of the large parcel of land of which he had theretofore disposed by the will above mentioned, inconsideration of the sum of P1 and other valuable considerations, among which were the payment of all his debts and obligations amounting to not less than P16,500, his maintenance up to his death, and the expenses of his last illness and funeral expenses. As to the northern half of the same parcel of land, he declared: "Hago constar tambien que reconozco a mi referido hijo Ernesto M. guevara como dueo de la mitad norte de la totalidad y conjunto de los referidos terrenos por haberlos comprado de su propio peculio del Sr. Rafael T. Puzon a quien habia vendido con anterioridad." On September 27, 1933, final decree of registration was issued in land registration case No. 15174 of the Court of First Instance of Pangasinan, and pursuant thereto original certificate of title No. 51691 of the same province was issued on October 12 of the same year in favor of Ernesto M. Guevara over the whole parcel of land described in the deed of sale above referred to. The registration proceeding had been commenced on November 1, 1932, by Victorino L. Guevara and Ernesto M. Guevara as applicants, with Rosario, among others, as oppositor; but before the trial of the case Victorino L. Guevara withdrew as applicant and Rosario Guevara and her co-oppositors also withdrew their opposition, thereby facilitating the issuance of the title in the name of Ernesto M. Guevara alone. On September 27, 1933, Victorino L. Guevarra died. His last will and testament, however, was never presented to the court for probate, nor has any administration proceeding ever been instituted for the settlement of his estate. Whether the various legatees mentioned in the will have received their respective legacies or have even been given due notice of the execution of said will and of the dispositions therein made in their favor, does not affirmatively appear from the record of this case. Ever since the death of Victorino L. Guevara, his only legitimate son Ernesto M. Guevara appears to have possessed the land adjudicated to him in the registration proceeding and to have disposed of various portions thereof for the purpose of paying the debts left by his father. In the meantime Rosario Guevara, who appears to have had her father's last will and testament in her custody, did nothing judicially to invoke the testamentary dispositions made therein in her favor, whereby the testator acknowledged her as his natural daughter and, aside from certain legacies and bequests, devised to her a portion of 21.6171 hectares of the large

parcel of land described in the will. But a little over four years after the testor's demise, she (assisted by her husband) commenced the present action against Ernesto M. Guevara alone for the purpose hereinbefore indicated; and it was only during the trial of this case that she presented the will to the court, not for the purpose of having it probated but only to prove that the deceased Victirino L. Guevara had acknowledged her as his natural daughter. Upon that proof of acknowledgment she claimed her share of the inheritance from him, but on the theory or assumption that he died intestate, because the will had not been probated, for which reason, she asserted, the betterment therein made by the testator in favor of his legitimate son Ernesto M. Guevara should be disregarded. Both the trial court and the Court of appeals sustained that theory. Two principal questions are before us for determination: (1) the legality of the procedure adopted by the plaintiff (respondent herein) Rosario Guevara; and (2) the efficacy of the deed of sale exhibit 2 and the effect of the certificate of title issued to the defendant (petitioner herein) Ernesto M. Guevara. I We cannot sanction the procedure adopted by the respondent Rosario Guevara, it being in our opinion in violation of procedural law and an attempt to circumvent and disregard the last will and testament of the decedent. The Code of Civil Procedure, which was in force up to the time this case was decided by the trial court, contains the following pertinent provisions: Sec. 625. Allowance Necessary, and Conclusive as to Execution. No will shall pass either the real or personal estate, unless it is proved and allowed in the Court of First Instance, or by appeal to the Supreme Court; and the allowance by the court of a will of real and personal estate shall be conclusive as to its due execution. Sec. 626. Custodian of Will to Deliver. The person who has the custody of a will shall, within thirty days after he knows of the death of the testator, deliver the will into the court which has jurisdiction, or to the executor named in the will. Sec. 627. Executor to Present Will and Accept or Refuse Trust. A person named as executor in a will, shall within thirty days after he knows of the death of the testor, or within thirty days after he knows that he is named executor, if he obtained such knowledge after knowing of the death of the testor, present such will to the court which has jurisdiction, unless the will has been otherwise returned to said court, and shall, within such period, signify to the court his acceptance of the trust, or make known in writing his refusal to accept it. Sec. 628. Penalty. A person who neglects any of the duties required in the two proceeding sections, unless he gives a satisfactory excuse to the court, shall be subject to a fine not exceeding one thousand dollars. Sec. 629. Person Retaining Will may be Committed. If a person having custody of a will after the death of the testator neglects without reasonable cause to deliver the same to the court having jurisdiction, after notice by the court so to do, he may be committed to the prison of the province by a warrant issued by the court, and there kept in close confinement until he delivers the will. The foregoing provisions are now embodied in Rule 76 of the new Rules of Court, which took effect on July 1, 1940. The proceeding for the probate of a will is one in rem, with notice by publication to the whole world and with personal notice to each of the known heirs, legatees, and devisees of the testator (section 630, C. c. P., and sections 3 and 4, Rule 77). Altho not contested (section 5, Rule 77), the due execution of the will and the fact that the testator at the time of its execution was of sound and disposing mind and not acting under duress, menace, and undue influence or fraud, must be proved to the satisfaction of the court, and only then may the will be legalized and given effect by means of a certificate of its allowance, signed by the judge and attested by the seal of the court; and when the will devises real property, attested copies thereof and of the certificate of allowance must be recorded in the register of deeds of the province in which the land lies. (Section 12, Rule 77, and section 624, C. C. P.) It will readily be seen from the above provisions of the law that the presentation of a will to the court for probate is mandatory and its allowance by the court is essential and indispensable to its efficacy. To assure and compel the probate of will, the law punishes a person who

neglects his duty to present it to the court with a fine not exceeding P2,000, and if he should persist in not presenting it, he may be committed to prision and kept there until he delivers the will. The Court of Appeals took express notice of these requirements of the law and held that a will, unless probated, is ineffective. Nevertheless it sanctioned the procedure adopted by the respondent for the following reasons: The majority of the Court is of the opinion that if this case is dismissed ordering the filing of testate proceedings, it would cause injustice, incovenience, delay, and much expense to the parties, and that therefore, it is preferable to leave them in the very status which they themselves have chosen, and to decide their controversy once and for all, since, in a similar case, the Supreme Court applied that same criterion (Leao vs. Leao, supra), which is now sanctioned by section 1 of Rule 74 of the Rules of Court. Besides, section 6 of Rule 124 provides that, if the procedure which the court ought to follow in the exercise of its jurisdiction is not specifically pointed out by the Rules of Court, any suitable process or mode of procedure may be adopted which appears most consistent to the spirit of the said Rules. Hence, we declare the action instituted by the plaintiff to be in accordance with law. Let us look into the validity of these considerations. Section 1 of Rule 74 provides as follows: Section 1. Extrajudicial settlement by agreement between heirs. If the decedent left no debts and the heirs and legatees are all of age, or the minors are represented by their judicial guardians, the parties may, without securing letters of administration, divide the estate among themselves as they see fit by means of a public instrument filed in the office of the register of deeds, and should they disagree, they may do so in an ordinary action of partition. If there is only one heir or one legatee, he may adjudicate to himself the entire estate by means of an affidavit filed in the office of the register of deeds. It shall be presumed that the decedent left no debts if no creditor files a petition for letters of administration within two years after the death of the decedent. That is a modification of section 596 of the Code of Civil Procedure, which reads as follows: Sec. 596. Settlement of Certain Intestates Without Legal Proceedings. Whenever all the heirs of a person who died intestate are of lawful age and legal capacity and there are no debts due from the estate, or all the debts have been paid the heirs may, by agreement duly executed in writing by all of them, and not otherwise, apportion and divide the estate among themselves, as they may see fit, without proceedings in court. The implication is that by the omission of the word "intestate" and the use of the word "legatees" in section 1 of Rule 74, a summary extrajudicial settlement of a deceased person's estate, whether he died testate or intestate, may be made under the conditions specified. Even if we give retroactive effect to section 1 of Rule 74 and apply it here, as the Court of Appeals did, we do not believe it sanctions the nonpresentation of a will for probate and much less the nullification of such will thru the failure of its custodian to present it to the court for probate; for such a result is precisely what Rule 76 sedulously provides against. Section 1 of Rule 74 merely authorizes the extrajudicial or judicial partition of the estate of a decedent "without securing letter of administration." It does not say that in case the decedent left a will the heirs and legatees may divide the estate among themselves without the necessity of presenting the will to the court for probate. The petition to probate a will and the petition to issue letters of administration are two different things, altho both may be made in the same case. the allowance of a will precedes the issuance of letters testamentary or of administration (section 4, Rule 78). One can have a will probated without necessarily securing letters testamentary or of administration. We hold that under section 1 of Rule 74, in relation to Rule 76, if the decedent left a will and no debts and the heirs and legatees desire to make an extrajudicial partition of the estate, they must first present that will to the court for probate and divide the estate in accordance with the will. They may not disregard the provisions of the will unless those provisions are contrary to law. Neither may they so away with the presentation of the will to the court for probate, because such suppression of the will is contrary to law and public policy. The law enjoins the probate of the will and public policy requires it, because unless the will is probated and notice thereof given to the whole world, the right of a person to dispose of his property by will may be rendered