Professional Documents

Culture Documents

NCTC Debate

Uploaded by

Sreekanth ReddyCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

NCTC Debate

Uploaded by

Sreekanth ReddyCopyright:

Available Formats

IPCS

Issue Brief

No. 181, March 2012

National Counter Terrorism Centre for India

Understanding the Debate

PR Chari Visiting Professor, IPCS.

Like many other issues in these troubled times, the proposal for establishing a National Counter-Terrorism Centre (NCTC) to coordinate the anti-terrorism efforts of the Union and the States has also become a plebiscitary dispute. This proposal, dear to the heart of Home Minister P Chidambaram, comes from the US after he studied its workings during a visit to the country. The need to coordinate the antiterrorism measures of the Union and State Governments had become apparent after the Mumbai attacks in November 2008 when several intelligence and operational failures came to light; hence, the need for a joint assault on terrorism is unexceptional. But, Chidambarams enthusiasm for the NCTC is not shared by the States and some 13 Chiefs Ministers, at last count, have voiced their misgivings about this modality. It is nobodys case that the State Governments are unconcerned about the recurring bomb explosions that have excoriated Delhi, Mumbai, Hyderabad, Varanasi and Ahmedabad. Their post-mortem reports have linked these events to terrorists from abroad acting either alone or in conjunction with domestic malcontents. Neither can be alleged that the several States afflicted by Naxalite violence are indifferent to the continuing loss of lives. Why, then, are these 13 Chief Ministers opposing this salubrious measure? It would be egregious to argue that they are indifferent to their responsibilities under the Indian Constitution, which confers on them the

legislative powers to raise police forces and maintain public order in their jurisdiction. It appears that these Chief Ministers, mostly heading non-Congress governments, believe that the Congress-led UPA government in New Delhi will use the NCTC to harass them. Is this angst unrealistic? Or, paranoid? I THE JUSTIFICATION FOR A CENTRALIZED COUNTER-TERRORISM INSTITUTION, AND ITS CAVEATS The Home Ministry has countered that a NCTC is unavoidable because, at present, the Union Government cannot deploy its military and para-military forces suo motu to deal with internal security problems in the States; often the States are unwilling to accept these Central forces due to dubious political compulsions. This has occurred when large-scale communal riots occurred in 1993 (post Babri Masjid) and 1992 (post Godhra). Moreover, the need for a NCTC is justified because the States lack the political will to fight determinedly against terrorism. Often the States have not deployed their police and state armed forces to deal firmly with law and order situations in a timely manner. Neither have they taken credible steps to professionalize these forces. They have also used their State forces to serve political ends, like the partisan use of the Gujarat police during the post-Godhra riots in 2002. These facts cast serious doubts on the impartiality and integrity of the State law and order apparatus.

Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies

1

B7/3, Safdarjung Enclave, New Delhi, 110029 91114100 1900 www.ipcs.org

THE NCTC DEBATE IN INDIA

Unfortunately, the record of the Union Government is equally questionable. The cases launched against those involved in the antiSikh riots of 1984 are still lingering, despite some three decades intervening. Besides, the failure of the Union government to deploy the Army in Mumbai during the anti-Muslim riots in 2003, despite their being available, reflected adversely on the impartiality of the government. Ironically, several of those involved in these dubious actions were appointed to high administrative and political positions or continue in them, which was not fortuitous. These blatant instances of partisanship and lack of integrity in the Union government apart, the professional ability of the Central police organizations is also arguable. The loss of 76 CRPF personnel of its 62nd battalion in the Dantewada district of Chhattisgarh in a clinically executed Naxalite ambush some two years back might be recollected here. Several questions had arisen then about the adequacy of their training, their physical fitness to undertake arduous jungle operations, and their familiarity with the terrain, language and culture of the local population. All this was found wanting in the post-mortem inquiry. Whether remedial steps have been taken to professionalize these forces currently deployed for counter-terrorism and antiNaxalite operations can only be speculated upon in the absence of any independent evaluation. The limited point being made here is that the Union forces are not much better than the State forces in dealing with terrorists and insurgents; so nave conclusions regarding their natural superiority are quite misplaced. Indeed, a strong argument can be made for strengthening the police stations and the local

police/ armed forces in the States; this would be more relevant to meeting the threat since they have local knowledge of the terrain, language and culture that are of equal, if not greater, significance for counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency operations. What are the legal provisions enabling the Union Government to deploy its armed forces (military and para-military) to provide internal security in the States? The Criminal Procedure Code permits any magistrate to call upon any available military unit to come to its aid for maintaining law and order. Once deployed the obtaining thesis is that these forces would use only the minimum force necessary to control the situation and, that too, in the last resort. The regulations require that, before any major deployment of troops in aid to civil authority, the State concerned must seek the prior approval of the Union Government. In theory, the Union Government needs to satisfy itself that the State concerned has explored all other options like using its own forces and other para-military forces belonging to the State and Union governments before seeking the armed forces of the Union. Attention might also be drawn here to the provisions of Article 355 of the Indian Constitution, which casts a duty upon the Union to protect every State against external aggression and internal disturbance. Consequently, New Delhi is empowered to deploy its armed forces to quell internal disturbance. This legal authority has never been exercised by the Union Government or opined upon by the law courts. A reference to the Supreme Court under Article 143 (1) is possible to seek its opinion on this important question of law. Possessing the legal authority to deploy the Union forces, suo motu, in the States must, however, be tailored to political realities. The UPA Government has been marked by vacillation and has retreated in confusion from its earlier policy decisions to allow FDI in multi-brand retail trade, amend the law on land acquisitions or empower the Lokayuktas under the Lokpal Bill. In each case the common refrain of the States was that New Delhi had failed to consult and convince them about the need for these measures. This is again being alleged about the NCTC 2 proposal.

The NCTC would function under the Intelligence Bureau (IB); it would analyze the intelligence pertaining to terrorism and associated criminality; maintain relevant data bases; develop appropriate responses; and undertake threat assessments for dissemination to the Union and State governments

2

IPCS ISSUE BRIEF 181, MARCH 2012

II WHY IS THE PROPOSAL ON HOLD? Somewhat belatedly, the apprehensions of the objectors are to be discussed by the Home Ministry with the State DGPs and Chief Secretaries. But, this exercise seems pointless, since the assent of the Chief Ministers will still be required. Their suspicions have been aroused about the intent behind the NCTC and the manner in which its draconian powers will be utilized; hence it will be very difficult to obtain their assent at this stage. Further, the results of the mini-general elections held recently in 5 States reveals that the Congress is losing popular support casting serious doubts on the ability of the UPA government to pursue radical proposals. The Union armed forces cannot function in the State(s) concerned unless their willing cooperation is available; otherwise they would be denied access to tactical intelligence, logistics support and face the possible resistance of the local administration. It would be useful now to describe the NCTC proposal. It would function under the Intelligence Bureau (IB); it would analyze the intelligence pertaining to terrorism and associated criminality; maintain relevant data bases; develop appropriate responses; and undertake threat assessments for dissemination to the Union and State governments. All this is unexceptional. But, the problem arises with the organization also being empowered to arrest suspects and undertake searches under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 without reference to the State Governments. A NCTC Standing Council is envisaged with representation from the States to ensure against arbitrary action, but this has failed to reassure them. Their resentments have also been fuelled because they were not consulted before the NCTC modality was finalized. Moreover, the absence of legislative oversight over the activities of the intelligence agenciesthis proposal has been resolutely resisted by Union governments in the past strengthens fears that these powers could be exercised in an arbitrary fashion. III THE INDIAN AND AMERICAN MODELS: A COMPARISON

The Indian NCTC has the power to investigate and arrest; hence it differs radically from its American counterpart, which has become the problem. Moreover, placing the NCTC within the Intelligence Bureau (IB) would convert the Bureau into an operational body, which would be disastrous for the general polity.

The American NCTC is part of its Directorate of National Intelligence, which is manned by officials from the Pentagon, FBI, CIA and related agencies who can access their databases. The Centre analyzes and collates terrorism related information to plan and support counterterrorism operations. Its charter visualizes its providing this information to the intelligence agencies for responding to terrorist incidents within the US, and also brief policymakers. Intelligence organizations perform two functions. They collect, collate and assess the information obtained from open and clandestine sources. Further, they also conduct intelligence operations to gather information, and undertake counterintelligence operations to disrupt the activities of their counterparts abroad. The American NCTC is only charged with the first of these functions viz to collect, collate and assess terrorism-related information, but not to conduct intelligence operations. It has no powers to investigate or arrest. The Indian NCTC has the power to investigate and arrest; hence it differs radically from its American counterpart, which has become the problem. Moreover, placing the NCTC within the Intelligence Bureau (IB) would convert the Bureau into an operational body, which would be disastrous for the general polity. It is an open secret that the IB assiduously gathers political intelligence on behalf of the political party in power about rival factions within the party and the Opposition parties. Equipping the IB with powers of arrest and search in the States is, therefore, being resisted by the States. Moreover, the NCTC would also get embroiled in IBs running battle with the Research and Analysis Wing (R&AW), which is responsible for 3 both external intelligence. Terrorism has

3

IPCS ISSUE BRIEF 180, JANUARY 2012

international and national aspects; hence, the NCTC must be separated from the IB to maintain equidistance from the IB and the R&AW. The US established its Department of Homeland Security after 9/11. In India the establishment of a separate Ministry of Internal Security, conceived several years back, continues to languish. Ideally, the NCTC should be placed under this new Ministry, along with the National Intelligence Agency (NIA), and relevant sections of the various intelligence agencies, including the National Information Grid (NATGRID), National Threat Reduction Organization (NTRO). The intention would be to integrate the information at all levels relating to terrorist and insurgent organizations for undertaking counter-terrorism and counterinsurgency operations. IV RECOMMENDATIONS First, the need for harnessing the joint efforts of the Union and State Government to fight the demon of terrorism is too obvious to need iteration. A conjoint expression of their commitment to pooling their intelligence and operational resources should be made in the next meeting of the Inter-State Council as a prelude to establishing the working arrangements. Second, the State Governments must strengthen their own intelligence and operational capabilities to address the menace of terrorism, including Left Wing Extremism. Their need for financial assistance should be considered sympathetically by New Delhi, but the emphasis has to be on agreed solutions being properly implemented. For instance, the additional forces catered for must be raised, training institutions must be upgraded, police stations authorized must be physically established, arms and ammunition sanctioned must be centrally purchased and supplied and so on. In short, a physical, apart from a financial, audit of devolved funds is necessary. Third, adequate arrangements are required to

ensure a continuing validation of the professional abilities of the Union and State forces employed in the anti-terrorism and counter-insurgency role. An independent Inspectorate can be suggested for this purpose that would function like an Ombudsman to evaluate the capability of these forces to undertake the challenging tasks confronting them. The need for this outside evaluation is all the more necessary since the intelligence agencies and their activities are not subject to Parliamentary oversightan idea whose time has also come. Fourth, an overall operational strategy needs to be devised. The cluster of questions arising is: How could the States be better enabled to handle anti-terrorism activities more confidently with their own human and material resources? Should the Union para-military forces be deployed only for special operations or routinely in lieu of State Police forces? In what combat or support role can the Indian Army and Air Force be deployed? Fifth, the underlying governance issues must be tackled to strengthen the anti-terrorism strategy. Obvious candidate are the establishment of special courts to try terrorismrelated offences with celerity, credible programs to ensure witness protection and ensure the anonymity of whistle-blowers, the prosecution of politicians and bureaucrats linked to such activities, an effective rotational postings policy for executive officers in the government, implementation of social services and development programsespecially those relating to education and public health and so on. The imperative need to coordinate the antiterrorism intelligence gathering and joint operational efforts of the Union and State governments needs no emphasis. The mechanics have to be reworked by joint consultations after a decent interval, since the present NCTC proposal can only be described as dead on arrival.

Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies

B7/3, Safdarjung Enclave, New Delhi, 110029; 91114100 1900

You might also like

- Service Allocation of 2013 Batch Civil ServantsDocument89 pagesService Allocation of 2013 Batch Civil ServantsSreekanth Reddy100% (3)

- Y V Reddy: Indian Economy - Current Status and Select IssuesDocument3 pagesY V Reddy: Indian Economy - Current Status and Select IssuesSreekanth ReddyNo ratings yet

- Sino-Indian Relations Contours Across The PLA Intrusion CrisesDocument6 pagesSino-Indian Relations Contours Across The PLA Intrusion CrisesSreekanth ReddyNo ratings yet

- Service Allocation of 2013 Batch Civil ServantsDocument89 pagesService Allocation of 2013 Batch Civil ServantsSreekanth Reddy100% (3)

- India's Gold Economy and Policy ReviewDocument11 pagesIndia's Gold Economy and Policy ReviewSreekanth ReddyNo ratings yet

- Direct and Indirect Effects of Fdi On Current Account: Jože Mencinger EIPF and University of LjubljanaDocument19 pagesDirect and Indirect Effects of Fdi On Current Account: Jože Mencinger EIPF and University of LjubljanaSreekanth ReddyNo ratings yet

- Foreign Trade Policy 2009-2014Document112 pagesForeign Trade Policy 2009-2014shruti_siNo ratings yet

- Social Reform MovementsDocument8 pagesSocial Reform MovementsSreekanth ReddyNo ratings yet

- New Scheme IFSE2013Document1 pageNew Scheme IFSE2013Sreekanth ReddyNo ratings yet

- 11 13 EngDocument9 pages11 13 EngPushan Kumar DattaNo ratings yet

- Ultra Mega ProjectDocument8 pagesUltra Mega ProjectSiddharth ManiNo ratings yet

- Indian ReformDocument34 pagesIndian ReformSreekanth ReddyNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Climate Change and India OUPDocument1 pageHandbook of Climate Change and India OUPSreekanth ReddyNo ratings yet

- Gatt 1994Document2 pagesGatt 1994anirudhsingh0330No ratings yet

- 2668Document2 pages2668Imelda RozaNo ratings yet

- IB DefenceOffsetGuidelines 050813Document6 pagesIB DefenceOffsetGuidelines 050813Sreekanth ReddyNo ratings yet

- Media EthicsDocument11 pagesMedia EthicsSreekanth Reddy100% (2)

- Sample Paper of Upsc EthicsDocument2 pagesSample Paper of Upsc EthicsKarakorammKaraNo ratings yet

- CH 05 PDFDocument17 pagesCH 05 PDFDrRaanu SharmaNo ratings yet

- Importance and Challenges of Ethics PDFDocument10 pagesImportance and Challenges of Ethics PDFDinesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Importance and Challenges of Ethics PDFDocument10 pagesImportance and Challenges of Ethics PDFDinesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Ethics in The History of Indian PhilosophyDocument12 pagesEthics in The History of Indian PhilosophySreekanth ReddyNo ratings yet

- Nature and Scope of EthicsDocument10 pagesNature and Scope of EthicsSreekanth ReddyNo ratings yet

- Union Budget 2011-12: HighlightsDocument14 pagesUnion Budget 2011-12: HighlightsNDTVNo ratings yet

- Cyber Security PolicyDocument21 pagesCyber Security PolicyashokndceNo ratings yet

- Disaster Management VIII Together Towards A Safer India Part-I @sina @maxiDocument63 pagesDisaster Management VIII Together Towards A Safer India Part-I @sina @maxiblu_diamond2450% (8)

- Seabuckthorn @sandeepDocument3 pagesSeabuckthorn @sandeepSreekanth ReddyNo ratings yet

- WHO - Climate Change and Human Health - Risks and Responses - SummaryDocument28 pagesWHO - Climate Change and Human Health - Risks and Responses - SummarySreekanth ReddyNo ratings yet

- Bt Brinjal Consultations Primer Issues ProspectsDocument26 pagesBt Brinjal Consultations Primer Issues ProspectsVeerendra Singh NagoriaNo ratings yet

- Nonalignment 2Document70 pagesNonalignment 2Ravdeep SinghNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Army Headquarters Vietnam Lessons Learned 24 Feburary 1971Document119 pagesArmy Headquarters Vietnam Lessons Learned 24 Feburary 1971Robert ValeNo ratings yet

- Grayisms - Selected Quotations of CMC Gen GrayDocument90 pagesGrayisms - Selected Quotations of CMC Gen GrayAaron Athanasius ZeileNo ratings yet

- French Acquisition of Italy: From Napoleon to Cavour's Unification EffortsDocument5 pagesFrench Acquisition of Italy: From Napoleon to Cavour's Unification EffortsMike Okeowo100% (2)

- Muhammadu BuhariDocument23 pagesMuhammadu BuhariMihai Iulian Păunescu100% (1)

- Salah Ezzedine FrauDDocument4 pagesSalah Ezzedine FrauDkksamahaNo ratings yet

- DafdfDocument10 pagesDafdfIyam LloydNo ratings yet

- Manila Standard Today - July 29, 2012 IssueDocument12 pagesManila Standard Today - July 29, 2012 IssueManila Standard TodayNo ratings yet

- Triptico Colores Sovieticos - BAJA PDFDocument2 pagesTriptico Colores Sovieticos - BAJA PDFLuis Francisco Soto100% (1)

- Emerging Defense Technologies November 2009Document45 pagesEmerging Defense Technologies November 2009TrixyblueeyesNo ratings yet

- Vietnam The Ten Thousand Day WarDocument6 pagesVietnam The Ten Thousand Day Warapi-37157340% (1)

- Resrep 11645Document29 pagesResrep 11645hanzNo ratings yet

- 217-301 Bai Tap Tieng Anh Lop 5Document6 pages217-301 Bai Tap Tieng Anh Lop 5Hoàng ChungNo ratings yet

- GoblinsDocument1 pageGoblinsJean Luke CachiaNo ratings yet

- Civil DisobedienceDocument19 pagesCivil DisobedienceRea PapakonstNo ratings yet

- US Review Sheet WWIDocument8 pagesUS Review Sheet WWIWB3000100% (2)

- Hide PART 1 - Hunter Exam ArcDocument4 pagesHide PART 1 - Hunter Exam ArcAhmad AsykhiyaniNo ratings yet

- Despotic Bodies and Transgressive Bodies Spanish Culture From Francisco Franco To Jesus FrancoDocument168 pagesDespotic Bodies and Transgressive Bodies Spanish Culture From Francisco Franco To Jesus FrancoWellesor1985No ratings yet

- Test Bank For Technology in Action 10th Edition EvansDocument24 pagesTest Bank For Technology in Action 10th Edition Evanscynthiagraynpsiakmyoz100% (41)

- A Thousand Cuts.Document1 pageA Thousand Cuts.ketsu matapangNo ratings yet

- Antiochus IV's Death and Philip's Return from the EastDocument14 pagesAntiochus IV's Death and Philip's Return from the EastNițceValiNo ratings yet

- Carlo Ginzburg 'Your Country Needs You' A Case Study in Political Iconography History Workshop Journal, No. 52 (Autumn, 2001), Pp. Vi+1-22Document24 pagesCarlo Ginzburg 'Your Country Needs You' A Case Study in Political Iconography History Workshop Journal, No. 52 (Autumn, 2001), Pp. Vi+1-22Vincent Mespoulet100% (1)

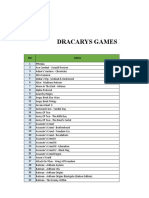

- Dracar Games PS3 CollectionDocument30 pagesDracar Games PS3 CollectionAntonius WibowoNo ratings yet

- German Armour Attacks Soviets in 1945 Hungary BattleDocument4 pagesGerman Armour Attacks Soviets in 1945 Hungary BattleJMMPdosNo ratings yet

- Weather Made To Order, Connecting The DotsDocument7 pagesWeather Made To Order, Connecting The Dots19simon85No ratings yet

- Premium Socket Keys and Set ScrewsDocument37 pagesPremium Socket Keys and Set ScrewsMiguel Angel MasNo ratings yet

- 290700H Jul 19Document22 pages290700H Jul 19nikaken88No ratings yet

- The Alexandrian System Cheat SheetDocument21 pagesThe Alexandrian System Cheat SheetOtavio Lhamas100% (2)

- After the War: Reconstructing Family, Nation and State in GreeceDocument159 pagesAfter the War: Reconstructing Family, Nation and State in GreeceMikeGNo ratings yet

- Kissinger, Henry A.-The Congress of Vienna. A Reappraisal PDFDocument18 pagesKissinger, Henry A.-The Congress of Vienna. A Reappraisal PDFTherionbeastNo ratings yet

- AFCAT GK Questions 2019Document19 pagesAFCAT GK Questions 2019Krishna PrasadNo ratings yet