Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Abstracts of Boeing

Uploaded by

Bhanu DwivedyOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Abstracts of Boeing

Uploaded by

Bhanu DwivedyCopyright:

Available Formats

University Presentations for William Swan: William Swan was the lead economist for Boeing Commercial Airplanes

1996-2005. He forecast air travel among all regions of the world for 20 years forward. This is the basis for Boeings long-range plans, and for the annual Current Market Outlook document, which is an industry standard forecast. As a aviation economist, Dr. Swan was responsible for understanding both the fundamentals of forecasts for country GDPs and also the mechanisms by which economic and industry developments cause air travel growth. Before joining Boeing, Dr. Swan worked at both United Airlines, American Airlines, and Hull Trading, a stock index options market maker. He was involved in operations research and strategic planning. Dr. Swans educational background includes a Ph.D. in Transportation Systems from M.I.T and time spent on the research staff of M.I.T.s Flight Transportation Lab. His undergraduate work was in Aeronautical Engineering at Princeton University. He also holds an appointment as a Visiting Professor at Cranfield University. Currently Dr. Swan is associated with Seabury Airline Planning Group, a small consulting and investment firm.

Three Mistakes We Made In Forecasting For over 40 years Boeing has published an annual forecast for the growth of air travel world wide. Current Market Outlook has become a standard reference for planners in government and industry. Major methodological changes in the forecast occurred in mid-1990s. These were a result of rethinking the data, methods, and models. It turns out standard approaches over-emphasized the effect of GDP. On the other hand, statistics found a convincing and cogent link between trade and travel, even though the data appeared entirely random. Finally, a startlingly simple approach established the hitherto elusive link between travel and service quality. This talk is a light-hearted review of the things we did wrong and fixed, and the things we are still worried about. It provides a bittersweet contrast between the ways of industry and academia. As a bonus we introduce Occams Toothbrushan entirely new, hopelessly backwards, and entirely unpublishable way industry does hypothesis testing, but doesnt realize it. (PPT only) Misunderstandings about Airline Growth Consolidation is a myth. Data suggest that the airline industry is not consolidating. Competition is either increasing or almost constant, depending on the type of measurement. Hubs are here to stay. A hub is an airport where many of the passengers are connecting to ongoing flights. The reason hubs are here to stay is that half the O-D travel in the world is in markets too small to be served nonstop. Fortunately, small markets are willing to pay. Hubbed carriers economic strength is observable in the US ticket price data. Growth has not lead to bigger airplanes. The trend in airplane size has been flat to declining, since 1985. The evidence is the same in all regions of the world and has been strong and persistent. Smaller is good: Big airplanes spend more time on the gate and turn slower, increasing system costs. For small airplanes, value is created by frequency. Noise is lower, per seat, in small planes than big. Finally, congestion as a driver towards large airplanes affects only

Page 1

the smallest designs. The share of the largest size shows significant decline. Fares are declining very little. Industry real yields have been declining at 2-3% a year, but cost savings do not need to match this pace. Longer trips and leisure markets both have lower yields, so yield can change as the mix changes, even while fares are stable. Data show flat business fares and leisure fares declining by 1% per year. Cost savings continue to match the decline in fares. Jets, high-bypass engines, revenue management, travel agency fees, and competitive wages have each had their turn in reducing costs. Todays focus is on industrial engineering airport processes. Tomorrow may see more direct flight paths with fewer ATC delays. Plan the future. A trend is a projection of past developments. A forecast is a trend where you know the reasons why. A good forecast does not change the trend, unless it has a reason why the underlying causes are changing. The future is different again from a forecast. The future is what we try to make happen, after we understand how things work. (PPT and paper) Airline Evolution A review of routes, fares, competition, regulation, bankruptcy, startups, and generally how the airline industry evolved, based on personal involvement in each of these aspects from a academic, airline, and aircraft manufacturer viewpoints. (PPT but no paper) Airline Route Developments: The Unexpected. Airline route networks can carry growing traffic volumes by using larger airplanes, by adding frequencies on existing routes, and by adding new routes. The natural expectation has been that growth will come in all three dimensions in the listed order of importance. The last 15 years of route growth suggests otherwise. Growth has been accompanied by little change in airplane sizes, and new routes have been nearly as strong a development as added frequencies on existing routes. It seems that network growth patterns cannot be anticipated based on simple intuition alone. Such unexpected results require substantial evidence in support plus some explanation of the reasons why. This paper offers some data and some explanations that begin the discussion. (many PPT versions, but no paper) Consolidation in the Airline Industry People commonly perceive that the airline industry is consolidating. By this they mean there are fewer and fewer airlines. It is true that numbers of major airlines have disappeared from the competitive marketplace. It is also true that numbers of other airlines have grown newly significant. A common and useful measure of the degree of competition is the Herfindahl. The intuitive version of this measure represents the number of competitors of equal size that would produce the same degree of competition as is measured in the market. Herfindahls for the number of airlines operating in major markets have been flat or rising, not falling. Numerical evidence does not support the idea that competition is diminishing to any significant degree. Consolidation in the form of mergers or takeovers of failing carriers may be part of the birth-and-death process expected in a competitive market place (PPT and paper) Prices, Fares, and Yields The most common measure of airline fares is average yield, which is the ratio of revenues to passenger-kilometers. This paper demonstrates that changes in yield overstate changes in fares. This is done first with a small numerical example, and second by comparison between US yield and ticket sample data. Average yield declines in part because long-haul travel is growing faster than short-haul, and leisure travel is growing faster than

Page 2

business. Both effects depress yields even when prices are not changed. Data suggests that business fares have been flat, while discount fares have been declining. (PPT but no paper) New Perspective on Fleet Planning Recent insights from world-wide data show weak correlation of airplane size with market size, past airplane size used, or new market entry. This presentation presents the evidence and attempts to put past fleet planning models in perspective. A tentative model is presented that could explain the otherwise demoralizing lack of pattern in fleet trends. (PPT but no paper) How Airlines Compete. Airlines compete in city-pair markets. Each airline in the market plans a schedule of departure times and offers a series of fares. The fundamentals of airlines competing are this: customers choose based on price and time, and those customers who find both airlines equal choose based on secondary characteristics we call quality. This simple model of the demand side leads to some compelling consequences on the supply side. The discussion below starts with the simplest possible model, and then adds several levels of realism to that foundation. Along the way, discussions trace the effect of the market reality on competing airlines. (PPT and paper) Pricing and Yield Management (PPT but no text paper): HISTORY development over the last 20 years PRICING why several prices for tickets YIELD MANAGEMENT making pricing work TYPE OF FARES 4 basic kinds BUSINESS FARES high value travel COACH FARE the posted fare DISCOUNT FARES tourists and vacations PROMOTIONAL FARES low fares to stimulate travel PRICE ELASTICITY traffic changes when fares change DILUTION the problem of everyone getting the lowest fare VOCABULARY "bucket," "authorization," and "nesting" USING THE RESERVATIONS SYSTEM an example of yield management FORECASTING DEMAND combining data and knowledge OVERBOOKING adjusting for No Shows SUMMARY OF YIELD MANAGEMENT

Spill Modeling for Airlines (Slides in Word, not PPT) Spill models estimate average passenger loads when demand occasionally exceeds capacity. Such models have been in use for over 20 years. The shape of the distribution of demand is discussed from both theory and observation. Sources of variance are identified and calibrated. Measurement problems and techniques are discussed. Two alternate spill formulas are presented. A model revision responds to changes in process caused by computer reservations systems and revenue management. The concept that spill losses should be valued at discount fares is discussed. The recapture of spilled demand is presented as well as when such a phenomenon is relevant. Comparison of various sources of error is included. Finally, the use of spill models in reverse to imply demand from load is shown to have poor accuracy. The paper is meant to offer to the literature a reference for basic use. It is the result of 20 years involvement in spill model derivations, calibrations, and applications. (Word slides and papers)

Page 3

Fewer Departures Mean More Noise at Airports The combination of certified noise limits and departure caps at airports moves airlines to use larger airplanes and lower frequencies to serve travel demand. However, the best available measures of noise annoyance suggest that large airplanes contribute more annoyance per passenger carried than more flights with smaller airplanes. These observations hold true based on allowable certificated noise levels. They are even more true based on trends in actual noise outputs. The conclusion is that moving to smaller airplanes and more frequencies, particularly within the larger long-haul fleets will reduce noise far more than departure limits. If these results prove true, market mechanisms based on contribution to noise annoyance is an effective way to reduce ground impacts. The current pattern of certification limits on airplanes and departure caps at airports may actually increase noise. (PPT and paper; fairly short) Consolidation in the Airline Industry. People commonly perceive that the airline industry is consolidating. By this they mean there are fewer and fewer airlines. It is true that numbers of major airlines have disappeared from the competitive marketplace. It is also true that numbers of airlines have grown newly significant. A common and useful measure of the degree of competition is the Herfindahl. The intuitive version of this measure represents the number of competitors of equal size that would produce the same degree of competition as is measured in the market. Herfindahls for the number of airlines operating in major markets have been flat or rising, not falling. Numerical evidence does not support the idea that competition diminishing. Consolidation in the form of mergers or takeovers of failing carriers may be part of the birth-anddeath process expected in a competitive market place. (PPT and paper) Aircraft trip cost parameters: A function of stage length and seat capacity This paper disaggregates aircraft operating costs into various cost categories and provides background for an engineering approach used to compute a generalized aircraft trip cost function. Engineering cost values for specific airplane designs were generated for a broad number of operating distances, enabling a direct analysis of the operating cost function and avoiding the problems associated with financial reporting practices. The resulting data points were used to calibrate a cost function for aircraft trip expenses, varying in seating capacity and distance. This formula and the parameter values are then compared to econometric results, based on historical data. Results are intended to be used to adjust reported costs such that conclusions about industry structure, based on cost regressions, correctly account for differences in stage lengths and capacities. A CobbDouglas cost function is also computed, providing elasticity parameters for both economies of density, through seat capacity, and distance. The usefulness of the results for route network design draw from the simple planar connection between frequency, capacity and costs. Although the Cobb-Douglas function is no less accurate, it is generally much less convenient for subsequent analysis. (PPT and paper)

Presentations not yet prepared as slides, but paper exists

Airline Demand Distributions for Revenue Management and Spill Both revenue management and airline schedule optimization need to characterize the distribution of likely

Page 4

demand outcomes. Sources have proposed both Gamma and Normal shapes for these distributions. Data suggests that a model combining both distributions is appropriate. The model explains when the Gamma shape will dominate and when the Normal will determine the shape. One consequence of this understanding is that Gamma shapes are probably better for revenue management and Normal for spill modeling. However, it takes a compound process combining the two to generate all the observed characteristics of various cases.

Airline Jet Fuel Hedging: theory and practice Most international airlines hedge fuel costs, but the theoretical justification is weak. This paper explores the nature and extent of airline fuel hedging and asks why airlines hedge. The availability of hedging instruments is first discussed, with the most liquid markets in crude and exchange traded contracts. Aviation fuel contracts are possible, but with counter-party risk. Most major passenger airlines with sufficient cash and credit now hedge at least part of their future needs. Hedging does protect profits against a sudden upturn in crude prices caused by political and consumer uncertainty leading to slower economic growth. However, if higher oil prices are induced by strong economic growth and oil supply constraints, hedging increases volatility with hedging gains reinforcing improved profits from higher traffic and improved yields. If hedging does not reduce volatility, it may still have an accounting role in moving profits from one time period to another, insure against bankruptcy and signal the competence of management to investors and stakeholders. Copies of most of these can be downloaded from: http://www.sauder.ubc.ca/Faculty/Research_Centres/Centre_for_Transportation_Studies/ William_Swan_Publications

Page 5

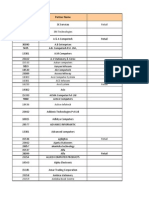

You might also like

- Assignment 2 - Innovation ManagementDocument15 pagesAssignment 2 - Innovation ManagementClive Mdklm40% (5)

- Air Traffic Management: Economics, Regulation and GovernanceFrom EverandAir Traffic Management: Economics, Regulation and GovernanceNo ratings yet

- Economic Instructor ManualDocument51 pagesEconomic Instructor Manualclbrack100% (10)

- Consumer Choices Tutorial Review 2Document7 pagesConsumer Choices Tutorial Review 2Lê Trần Hoàng TrọngNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Airline IndustryDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Airline Industryafmzhfbyasyofd100% (1)

- Airline Industry StructuresDocument3 pagesAirline Industry StructuresTalent MuparuriNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Topics On Low Cost AirlinesDocument8 pagesDissertation Topics On Low Cost AirlinesWriterPaperOmaha100% (1)

- Bilotkach 2015 Are Airports Engines of Economic Development A Dynamic Panel Data ApproachDocument17 pagesBilotkach 2015 Are Airports Engines of Economic Development A Dynamic Panel Data ApproachGabriel BordeauxNo ratings yet

- Airport Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesAirport Literature Reviewafmzydxcnojakg100% (1)

- Airline Industry Master ThesisDocument7 pagesAirline Industry Master ThesisCustomNotePaperUK100% (2)

- Airlines ThesisDocument5 pagesAirlines Thesismelissalongmanchester100% (1)

- Bachelor Thesis Low Cost CarrierDocument8 pagesBachelor Thesis Low Cost Carrierbsr6hbaf100% (1)

- Dissertation Topics AirlinesDocument5 pagesDissertation Topics AirlinesWriteMyPaperForMeUK100% (1)

- Low Cost Airline Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesLow Cost Airline Literature Reviewchrvzyukg100% (1)

- Literature Review of AirportDocument8 pagesLiterature Review of Airporttus0zaz1b1g3100% (1)

- An Analysis of The Causes of Flight DelaysDocument9 pagesAn Analysis of The Causes of Flight DelaysRaouf NacefNo ratings yet

- KPI in Airline IndustryDocument22 pagesKPI in Airline Industrygharab100% (1)

- Airline and Airport Dissertation IdeasDocument8 pagesAirline and Airport Dissertation IdeasWritingPaperServicesCanada100% (1)

- Non Aviation Revenue in Airport BusinessDocument20 pagesNon Aviation Revenue in Airport BusinessciciaimNo ratings yet

- Tracing The Woes: An Empirical Analysis of The Airline IndustryDocument44 pagesTracing The Woes: An Empirical Analysis of The Airline IndustrySagar HindoriyaNo ratings yet

- A Case Asdsaddsf - SADSADWWSACXZCDocument18 pagesA Case Asdsaddsf - SADSADWWSACXZCSyed SyafiqNo ratings yet

- GayleBrownPaperJanuary 2015Document40 pagesGayleBrownPaperJanuary 2015lenaw7393No ratings yet

- Master Thesis Airline IndustryDocument4 pagesMaster Thesis Airline Industryerinperezphoenix100% (2)

- Low Cost Carrier DissertationDocument7 pagesLow Cost Carrier DissertationCustomWrittenPapersCanada100% (1)

- 2013 - Evolving Trends of US Domestic AirfaresDocument34 pages2013 - Evolving Trends of US Domestic AirfaresZorance75No ratings yet

- Airline Industry Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesAirline Industry Literature Reviewea7sfn0f100% (1)

- Paper F2nbEZhhDocument42 pagesPaper F2nbEZhhdiamond WritersNo ratings yet

- Punctuality: How Airlines Can Improve On-Time Performance: ViewpointDocument20 pagesPunctuality: How Airlines Can Improve On-Time Performance: ViewpointDeepak LotiaNo ratings yet

- Cruising to Profits, Volume 1: Transformational Strategies for Sustained Airline ProfitabilityFrom EverandCruising to Profits, Volume 1: Transformational Strategies for Sustained Airline ProfitabilityNo ratings yet

- Airline Cost PerformanceDocument48 pagesAirline Cost PerformanceDidi Suprayogi Danuri100% (1)

- Chapter 1 PID - Youssef AliDocument15 pagesChapter 1 PID - Youssef Alianime brandNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Low Cost CarriersDocument8 pagesLiterature Review Low Cost Carriersmwjhkmrif100% (1)

- Dana Orlov08Document28 pagesDana Orlov08lenaw7393No ratings yet

- Research Paper Airline DeregulationDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Airline Deregulationaflefvsva100% (1)

- LC Airline Distribution ManagementDocument34 pagesLC Airline Distribution ManagementHuifeng LeeNo ratings yet

- ServiceCompetitionInTheAirlineIndus PreviewDocument45 pagesServiceCompetitionInTheAirlineIndus PreviewMaryrose A. DivinagraciaNo ratings yet

- Dissertation On AirlinesDocument7 pagesDissertation On AirlinesWhereToBuyWritingPaperGilbert100% (1)

- WestJet Charles ProjectDocument27 pagesWestJet Charles Projectinderdhindsa100% (2)

- Benchmarking Selected European Airports by Their Profitability Frontier - Branko Bubalo - PUBLIC - 2012Document16 pagesBenchmarking Selected European Airports by Their Profitability Frontier - Branko Bubalo - PUBLIC - 2012bbubaloNo ratings yet

- Articulo Kwoka SSRN-id1275841 1Document49 pagesArticulo Kwoka SSRN-id1275841 1Fred SaundersNo ratings yet

- Zhang 2020Document24 pagesZhang 2020Ebrahim KasaeyanNo ratings yet

- 54 Rafael Bernardo Carmona Benitez-Design of Large Scale Airline NetworkDocument3 pages54 Rafael Bernardo Carmona Benitez-Design of Large Scale Airline NetworkW.J. ZondagNo ratings yet

- Southwest 5 FORCESDocument11 pagesSouthwest 5 FORCESBvvss RamanjaneyuluNo ratings yet

- The Key Success FactorsDocument16 pagesThe Key Success Factorslavender_soul0% (1)

- 2005 MROBusiness PaperDocument17 pages2005 MROBusiness PaperRoxy Suwei DotkNo ratings yet

- Delta StrategicDocument43 pagesDelta StrategicUmair Ibrar100% (3)

- Energies: The Peculiarities of Low-Cost Carrier Development in EuropeDocument19 pagesEnergies: The Peculiarities of Low-Cost Carrier Development in EuropeElsa SilvaNo ratings yet

- Threat of New Entrants (Barriers To Entry)Document4 pagesThreat of New Entrants (Barriers To Entry)Sena KuhuNo ratings yet

- Low-Cost Strategy in The Air Air ArabiaDocument15 pagesLow-Cost Strategy in The Air Air ArabiaEsther CostaNo ratings yet

- Financial Performance and Customer Service An Examination Using Activity Based Costing of 38 International Airlines 2012 Journal of Air Transport ManaDocument3 pagesFinancial Performance and Customer Service An Examination Using Activity Based Costing of 38 International Airlines 2012 Journal of Air Transport ManaLilian BrodescoNo ratings yet

- Thesis Airline IndustryDocument8 pagesThesis Airline Industryannashawpittsburgh100% (2)

- Southwest Airlines Business EvaluationDocument38 pagesSouthwest Airlines Business EvaluationHansen SantosoNo ratings yet

- Low Cost Carrier Research PaperDocument7 pagesLow Cost Carrier Research Paperd1fytyt1man3100% (1)

- B J Atc U F:: Usiness Ets and Ser EesDocument40 pagesB J Atc U F:: Usiness Ets and Ser EesreasonorgNo ratings yet

- Analyze The Industry Environment of JetBlueDocument8 pagesAnalyze The Industry Environment of JetBlueshivshanker biradarNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Airline Mergers On On-Time Performance: A Case Study of The Delta-Northwest MergerDocument21 pagesThe Effect of Airline Mergers On On-Time Performance: A Case Study of The Delta-Northwest Mergeranaconda060% (1)

- Research Paper On Airline IndustryDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Airline Industryhyxjmyhkf100% (1)

- The Industry Handbook: The Airline Industry: Printer Friendly Version (PDF Format)Document21 pagesThe Industry Handbook: The Airline Industry: Printer Friendly Version (PDF Format)Gaurav JainNo ratings yet

- Airport BenchmarkingDocument16 pagesAirport Benchmarkingeeit_nizamNo ratings yet

- Airline IndustryDocument8 pagesAirline IndustryKrishnaPranayNo ratings yet

- Innovation in Aviation - A Case Study of United AirlinesFrom EverandInnovation in Aviation - A Case Study of United AirlinesNo ratings yet

- Session Plan Product ManagementDocument1 pageSession Plan Product ManagementBhanu DwivedyNo ratings yet

- Project 3610Document192 pagesProject 3610Bhanu DwivedyNo ratings yet

- Chap 6Document33 pagesChap 6Md. Ashraf Hossain SarkerNo ratings yet

- 395 PromotionsDocument42 pages395 Promotionssakash314_800874032No ratings yet

- Ambition Has No Rest - BhanuDocument1 pageAmbition Has No Rest - BhanuBhanu DwivedyNo ratings yet

- Snapdeal Returns Form PartialDocument1 pageSnapdeal Returns Form PartialsailaabNo ratings yet

- Snapdeal Returns Form PartialDocument1 pageSnapdeal Returns Form PartialsailaabNo ratings yet

- Management LessonsDocument6 pagesManagement LessonsBhanu DwivedyNo ratings yet

- N Some Software Development Projects The Requirements Supporting The Business Objectives Are Easily DefinedDocument17 pagesN Some Software Development Projects The Requirements Supporting The Business Objectives Are Easily DefinedBhanu DwivedyNo ratings yet

- TridentDocument2 pagesTridentBhanu DwivedyNo ratings yet

- Criteria For Evaluation Usage of Items (10marks) Clarity of Poster/Idea (10 Marks) Presentation (10 Marks) Total (50 Marks)Document2 pagesCriteria For Evaluation Usage of Items (10marks) Clarity of Poster/Idea (10 Marks) Presentation (10 Marks) Total (50 Marks)Bhanu DwivedyNo ratings yet

- Moving AveragesDocument29 pagesMoving AveragesBhanu DwivedyNo ratings yet

- Corporate News: 1) Google To Float Helium Balloons Over Rural India For Internet ConnectivityDocument2 pagesCorporate News: 1) Google To Float Helium Balloons Over Rural India For Internet ConnectivityBhanu Dwivedy0% (1)

- ORDocument52 pagesORBhanu Dwivedy100% (1)

- ReportDocument1 pageReportBhanu DwivedyNo ratings yet

- Solutions: ECO 100Y Introduction To Economics Midterm Test # 2Document15 pagesSolutions: ECO 100Y Introduction To Economics Midterm Test # 2examkillerNo ratings yet

- Durand - Indicators of International Competitiveness - Conceptual Aspects and EvaluationDocument51 pagesDurand - Indicators of International Competitiveness - Conceptual Aspects and EvaluationelvinsetanNo ratings yet

- HandicraftDocument19 pagesHandicraftFaizul Haque Shimul0% (1)

- OligoDocument13 pagesOligoSona VermaNo ratings yet

- Chap 21Document14 pagesChap 21Razman BijanNo ratings yet

- Business Plan ProposalDocument23 pagesBusiness Plan ProposalPudge Pudge'sNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document2 pagesChapter 4Dai Huu0% (1)

- Chapter 5C: The Functions of The Price MechanismDocument3 pagesChapter 5C: The Functions of The Price MechanismAmmaar KIMTI100% (1)

- Conceptual Framework of The Study Input Process OutputDocument3 pagesConceptual Framework of The Study Input Process OutputAlaida CatacutanNo ratings yet

- Powerpoint Lectures For Principles of Economics, 9E by Karl E. Case, Ray C. Fair & Sharon M. OsterDocument28 pagesPowerpoint Lectures For Principles of Economics, 9E by Karl E. Case, Ray C. Fair & Sharon M. Osterdant elNo ratings yet

- Holidays Assignment (2012-13) Class Xii Sub: PhysicsDocument11 pagesHolidays Assignment (2012-13) Class Xii Sub: PhysicsSankarNo ratings yet

- Vorlesung 05 PDFDocument16 pagesVorlesung 05 PDFSakshi AroraNo ratings yet

- The Potential Change of Food Delivery Market Among The Covid-19 PandamicDocument5 pagesThe Potential Change of Food Delivery Market Among The Covid-19 PandamicChi NguyenNo ratings yet

- 9708 Economics: MARK SCHEME For The October/November 2006 Question PaperDocument4 pages9708 Economics: MARK SCHEME For The October/November 2006 Question PaperKarmen ThumNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11 Monopolistic Competition OligopolyDocument40 pagesChapter 11 Monopolistic Competition OligopolyprachiprachiNo ratings yet

- Pricing Decision Support SystemsDocument19 pagesPricing Decision Support SystemsYasemin OzcanNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/21Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/21Sraboni ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- The Demand Function For Product X Is Given byDocument8 pagesThe Demand Function For Product X Is Given byAnderson AliNo ratings yet

- ECO 415 CH 3 eLASTICITYDocument10 pagesECO 415 CH 3 eLASTICITYMohd ZaidNo ratings yet

- Behavioral Economics ReedDocument21 pagesBehavioral Economics ReedLandoGuillénChávezNo ratings yet

- Presentation Real Estate Asset and Space MarketingDocument30 pagesPresentation Real Estate Asset and Space Marketinggaret matsileleNo ratings yet

- PEST Analysis: The Case of E-ShopDocument6 pagesPEST Analysis: The Case of E-ShopTI Journals PublishingNo ratings yet

- Distribution Channel ReportDocument23 pagesDistribution Channel ReportTalha RiazNo ratings yet

- BBA 312 Managerial Economics Assignment 2 SibongileDocument9 pagesBBA 312 Managerial Economics Assignment 2 SibongileLukiyo OwuorNo ratings yet

- ECO Group AssignmentDocument8 pagesECO Group AssignmentNhat HuyyNo ratings yet

- Deccan Industries: Summary of Rated InstrumentsDocument6 pagesDeccan Industries: Summary of Rated Instrumentsmohamed shufiyanNo ratings yet

- Solution Practice TestDocument12 pagesSolution Practice TestNgọc KhanhNo ratings yet

- Market: Imba Nccu Managerial Economics Jack WuDocument30 pagesMarket: Imba Nccu Managerial Economics Jack WuMelina KurniawanNo ratings yet