Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Prelim

Uploaded by

Melanie Joy Camarillo YsulatCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Prelim

Uploaded by

Melanie Joy Camarillo YsulatCopyright:

Available Formats

United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG)

Introduction: The considerable increase in international commerce in recent decades has spurred efforts to unite international commercial law . The United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG) represents a major outcome of these hard works . The CISG reflects challenging interests in present-day international commercial relations. Trade often crosses legal and ideological boundaries common and civil law systems, capitalist and socialist governments and industrialised and developing nations; the effort to create international legal regimes must deal with these differences. The unification effort must accordingly make not only technical, but also fundamentally political choices .

Objectives of CISG and its achievements: The objectives of CISG are articulated in its preamble. CISG is predicated upon recognition that the development of international trade on the basis of equality and mutual benefit is an important element in promoting friendly relations among states and more particularly the recognition that the adoption uniform rules which govern contracts for the international sale of goods and take into account different social ,economic and legal systems would contribute to the removal of legal barriers in international trade and promote the development of international trade . The perfect and reasonable outcome of the process that led to the adoption of CISG would be the worldwide ratification of the convention by all states, with the result that, in the normal course, a common legal code of rules dealing with international sales contracts

would be applicable to international sales contracts. Buyers and sellers on the global market therefore would have a comparatively simple and common uniform system governing their contracts and their performance. The alternative would be a potentially very complex latticework of individual State sales law regimes, resort to which was dictated by the rules of private international law applying in each jurisdiction .There would be ambiguity at two levels :which forums law applies, and the requirements of this law. Typically, in such case, one party would benefit from having his or her own jurisdictions law applied, and the other party would be in a less favourable position by the application of a foreign and possibly poorly understood law. The convention has not been universally adopted of course(e.g.: United Kingdom, India, Japan and Brazil etc), but to the extent that it is, the benefits of a uniform sales law regime in International Sales become more widespread .

Provisions of CISG, promoting its objectives: CISG, Uniformity, Internationality, other objectives and its application: Its very beginning, on the basis of Uniform Law of Sales and Uniform Law of Formation, makes it a natural device of uniform law. This is true with regard to the aim of the CISG, uniform law for international sales contracts to eliminate the trade barriers in international trade. Then its Preamble describes: The adoption of uniform rules, which govern contracts for the international sale of goods and take into account the different social, economic and legal systems, would contribute to the removal of legal barriers in international trade and promote the development of international trade. Then interpretation of Article 7(1) clearly explains, regard is to be had to its international character and the need to promote uniformity in its application . CISG ensured, systematic advancement of economic activities on a fair and equal basis because of lively participation of developing as well as industrialised nations. The predecessors of CISG were alleged to be in favour of the sellers of the developed nations, but CISG has additional buyer oriented provisions . In private commercial law field, the speciality of CISG is that, it is not dealing with procedure and conflicts ,but with substantive contract law .Once the sale is within the scope of CISG ,those who shop for forum cannot shop for law and if contracting parties are residents in a CISG states, the National Courts and International Arbitrators are no longer need to choose between different National Laws of sale . CISG deals with two aspects of the sales transaction, (I) the formation of contracts for international sale of goods, and (II) the rights and obligations of parties to these sales contracts . The CISG will apply, if the parties to the contract have their places of business in different Contracting States (Article 1(1) (a)).

If a party has more than one place of business, the relevant place of business is the one most closely connected to the sales transaction (Article 10 (a)). The CISG will also apply, when the parties' places of business are in different States and conflict of laws rules point to the application of the law of a Contracting State (Article 1(1) (b)). Under article 1(1) (b), the CISG could apply where only one party has its place of business in a Contracting State and, possibly, where neither party has its place of business in a Contracting State. However, any Contracting State at its will can make a reservation under article 95, that it will not bind by article 1(1) (b) . The main theme of the CISG is the role of the contract made by the parties, i.e. CISG recognises the principle of freedom of contract, according to Article 6, and CISG parties are free to exclude the application of the Convention or derogate from or vary the effect of its provisions. In other words, the application of the CISG is increased by the recognition of the principle of freedom of contract. Within the scope of Article 7 (Interpretation of CISG), which is consistent with its nature and function. Since the CISG has an important function, i.e. to replace diverse domestic laws with uniform international law, with the observance of good faith in international trade. Then with regard to Article 9 (Trade usages and practices within the scope of CISG), which is considered as one the most significant characteristics of the CISG, because it gives legal effect to trade usages and practices through their application to the contracts of International Trade .

Instances of certainty in CISG : a) Receipt Theory and Dispatch Theory: Different legal systems have different rules regarding an offerees acceptance and its binding on the offeror. According to Anglo-American mailbox rule, a binding contract is established at the moment of dispatch and some other legal systems fix receipt as the operative moment. CISG also follows receipt rule (Article 15 and Article 18) .Through this CISG encourages certainty in this issue. b) Communication and Parties: Almost all the legal systems have common principles and policies regarding disclosure of information between contracting parties. The CISG provisions also impose a duty on

contracting parties to disclose material information . c) Transfer of Risk: CISG adopted a straightforward rule, risk passes to the buyer when the goods are handed over to the carrier . This rule works against classic principle of documentary transactions. Even then, CISG promotes simple rule in international trade.

Critique of CISG Provisions: The convention seeks to maintain a delicate balance between the contrasting attitudes and concepts of the civil law and of the common law, and very often rules have to be blurred or omitted altogether in order to produce an acceptable compromise. It is certainly the case that the very restricted view of fundamental breach in Article 25, coupled with the vagueness of the provisions, is widely considered to make the convention unsuitable for use in documentary sales , where the doctrine of strict compliance, particularly in relation to letters to credit holds away, or in sale of commodities, which typically involve rapidly fluctuating markets, long chains of parties and potential exposure to huge amounts of damages, all of which necessitate a high degree of legal predictability . The convention governs only the formation of the contract and the rights and obligations of the seller arising from it. According to Article 4, CISG is not concerned with the validity of the contract or any of its provisions or of any usage, nor with the effect the contract may have on the property in the goods sold .

The Koblenz Oberlandesgericht has held that the convention does not apply to the validity of a retention of title clause. (Case No 5 U 534/91, [1992] Unilex D 92-4)

The convention is not concerned with the proprietary effects of the contract, nor with title conflicts between seller or buyer and a third party. Add to this the fact that CISG has nothing to say about CIF, FOB and combined transport transactions, and it will be apparent that the scope of the convention remains limited .

The weakness of CISG provisions are : 1. The contradictory provisions in Article 14 and 55 with regard to the determination of the price as a vital term of the contract.

2. The inconsistency between right to care and the right to avoid a contract for fundamental breach in Articles 48 and 49. 3. The doubtful status of good faith as a performance standard in CISG. 4. The implication of validity in Article 4 and impediment in Article 79. 5. Other concerns rose in opposition to CISG are validity of penalty clause, prescription period for determination of claims. Choice of forum for dispute resolution, the existence of a company, agency relationship, right of a party to counterbalance claims, currency in which payment should be made. 6. The right to interest without providing a rate formula leaves a gap in the CISG structure that creates uncertainty about how to compensate a creditor, when parties did not pick either a rate or a national law to cover gaps in the contract (Article.78) .

The compromises, during the legislative process of the CISG appeared in several forms : 1. A principle rule with exceptions. 2. A rule accommodating many types of doctrines or a rule consisting of conflicting or at least unresolved subparts.

The following examples reveal the significance of these issues : 1) Trade Usages : The Developing countries feared that the traditional concept of trade usages would favour industrialized western nations. The disputes were general versus local usages and traditional versus contemporary usages. On the issue of general versus local usages, CISG approved a standard of objective observance. However, it did not specified whose observance shall be the measure of objectivity or what prescriptive standard might guide that determination. Then on the issue of traditional versus contemporary usages , the drafters adopted a standard or regular observance. This standard did not specified, when a usage becomes regular.

Dixon, Irmaos & Cia, Ltd v. Chase National Bank, 144 F.2d 759 (2d Cir. 1944)

The lack of guidance concerning whose usage matters is fatal, when a seller observes general usages and a buyer observes local usages. 2) Good faith : Different legal systems attach different meanings to common doctrinal terms. The good faith provision of the CISG represents an agreement to impose some requirement of good faith in international commercial dealings, but it reflects no deeper consensus on the meaning of the application of the term. Therefore, National Courts are free to draw on domestic lines and have diverse conceptions of good faith .This will lead to conflicting interpretations of the term from different National courts. 3) International and Domestic Law; The Problem of Gap Filling : The ability of CISG to provide general principles that could fill the gaps in the explicit provisions was always under suspicion. So to resolve these issues two-step procedure were adopted. Explicit provisions should be interpreted in the light of the CISGs international character, if it does not resolve the question; the adjudicator should seek an answer in the CISGs general principles. If no general principle apply to the case, the adjudicator should seek to fill the gap in the CISG on the basis of the law applicable by virtue of the rules of private international law. This again increased the uncertainty in CISG. 4) Excuses for Non-performance : The CISG provision on excuse is a compromise between the common law impossibility doctrine and the civil law force majeure doctrine (Article 79). The former doctrine views impossibility as an exception to absolute liability and a justification for automatic termination of the contract. The latter doctrine regards impossibility as an excuse for non-performance based on the lack of fault and therefore bars any claim for damages. This provision creates only an illusion of certainty, it gives parties an incentive not to fix a particular governing doctrine by private agreement, and hence it may ultimately undermine contractual relations. 5) Reduction of Price Remedy : Despite theories that the civil law and the common law are converging, the attempt to incorporate essentially civil law or common law doctrine into the CISG met with considerable difficulty in several cases. CISG adopts the civil law doctrine that if goods delivered do not conform to the contract, the buyers remedy is an appropriate reduction in the contract price. So considerable opposition from common law supporters, then it was made consistent with the CISGs other breach of contract provisions. This again brought uncertainty.

CISG can be further developed through Judicial Interpretation: The uniform application of a supposedly uniform text will correct the texts latent defects. The courts of different countries are the ultimate interpreters of international law. This is true in the case of CISG as well. By its character, CISG is a complex document to change or amended. Moreover, it is an international treaty. Amendments needs approval by each signatory state before it can become effectual. CISG cannot easily change, so it is identified as a weakness of CISG. However, these problems can be solved through greater dependence on courts . Uniform law requires a new common law in which foreign precedents would not be precedents of a foreign law but of uniform law. Governmental legislation sets in place uniform law, but in reality, uniform law is not the work of governmental legislation. It is a creation of jurists, a kind of jurisconsultorium. Courts have to develop their jurisprudence in company with the courts of other countries from case to case . Air France v. Saks (United States) Interpretation of an international convention by the courts of signatory states should be given considerable weight. They should be taken into account in a comparative and critical manner . Case law is one of several aids to interpretation and Uniform Law doctrine (scholarly writings) and legislative history should be considered. These observations are true in the case of CISG as an international treaty . Pratt & Whitney v. Malev Hungarian Airlines It involved many issues in CISG, contract interpretation (Articles 7 and 8), the sufficiently definite offer (Article 14), and the supply of an open price term (Article 55) . Therefore, once again the objectives of CISG are established.

Conclusion: The convention was drafted in light of common law and civil law concepts and principles, but it is intended to be a self - contained body of law to be interpreted without resort to common law or civil law precepts . The CISG is considered to be a considerable success, because it has been ratified by most of the major trading nations of the world, tested in thousands of cases and arbitral hearings in many world jurisdictions and became subject of exhaustive academic commentary. These exposures to practice and critical commentary

exposed gaps and weaknesses of the convention, but the same can be found in any legal mechanism. Generally, CISG has proved to be a workable instrument in practice and produced reasonable results in majority of cases .

Bibliography: 1. Merryman , On the Convergence (and Divergence) of the Civil Law and the Common Law (1981) , Standard International Law Journal. 2. Hannold, A Uniform Law of International Sale. 3. Farnsworth, Developing International Trade Law (1979) 4. Graveson R, One Law On Jurisprudence and The Unification of Law (1979) 5. United Nations Convention on International Sale of Goods [1980] 6. Moens.G and Gillier , P , International Trade and Business Law ,Policy and Ethics, Routledge- Cavendish (2006) 7. Anderson, C.B , The Uniform International sale Law and the Global Jurisconsultorium 8. Dr. Ruangvichathoms Thesis 9. Joseph , M, Loose Ends of Contorts in International Sales : Problems in the Harmonization of Private Law Rules ,American Journal of Comparative Law. 10. Unification and Certainty: The United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, Harvard Law Review (1984). 11. Bridge, M , Uniformity and Diversity in the Law of International Sale. 12. Goode ,R , Commercial Law ,Penguin Books (2004) 13. Jacob S.Ziegal, The UNIDROIT Contract Principles, CISG and National Law 14. Karin L.Kizer , Minding The Gap: Determining Interest Rates Under the UN Convention for the International Sale of Goods, University of Chicago Law Review. 15. Paul Amato , UN Convention on International Sale of Goods The open Price Term and Uniform Application: An Early Interpretation By the Hungarian Courts.

16. www. cisg. pace.edu/cisg/text/caseschedule.html 17. www. cisg.pace.edu/cisg/text/harvard-note.html 18. Goode ,R, et al Transnational Commercial Law , Oxford University Press (2007) 19. Indira Carr , International Trade Law, Cavendish Publishing Company. 20. John Felemegas, An International approach to Interpretation of the United Nations Convention on contracts for the International Sale of Goods as Uniform Sales Law, Cambridge University Press. 21. Albert H.Kritzer, Guide to Practical Applications of the UN convention on contracts, Kluwer Law & Taxation Publishers (1990) 22. Nina M. Glaston, International sales: The United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (1984).

Although the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods ("CISG) was enacted in 1980 when e-commerce was still a distant prospect, its precepts are applicable international law for e-commerce nowadays. E-commerce involves contracts for the international sale of goods, among others. Thus, CISG is a significant international legislative tool for cross-border e-commerce contracts. This article explores the CISG precepts and its relevancy for e-commerce contracts.

Join the Internet Law Forum (ILF) to... discuss, share information and knowledge, questions and doubts... regarding the legal aspects of the Internet. The ILF is ALL about the INTERNET... business, laws and regulations, social media... Sign up to enjoy the benefits of the Free Global membership in the IBLS international community!

contracts. This article explores

Although the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods ("CISG") was enacted in 1980 when ecommerce was still a distant prospect, its precepts are applicable international law for e-commerce nowadays. E-commerce involves contracts for the international sale of goods, among others. Thus, CISG is a significant international legislative tool for cross-border e-commerce the CISG precepts and its relevancy for e-commerce contracts.

The United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods ("CISG") applies to contracts for the sale of goods between parties whose businesses are located in different states, when the States are acting as Contracting States; or when private companies, applying private international law, choose the law of the Contracting State. CISG, art. 1. Therefore, e-commerce businesses transacting in goods on a large international scale may seek uniformity, if advantageous for them, on their international contracts by applying CISG contract formation rules to their e-commerce contracts. Moreover, e-government procurement contracts between nations may also be subject to CISG if the

Contracting States so agree. CISG rules are limited to the formation of contracts of sale and the sellers' and buyers" obligations and rights arising out of those international trade contracts. It is important to note that CISG rules may be more effectively applied to the formation of B2B (business to business) e-commerce contracts or B2G (business to government), or G2G (government to government) contracts rather than B2C (business to consumers) e-commerce contracts. The reason for this is that CISG is not applicable to the sale of goods bought for personal, family, or household use. Commonly, in B2C e-commerce contracts individuals buy goods online for their personal or family use. Also, CISG does not apply to good bought through auctions (like online auctions), stocks, shares, investment securities, ships, vessels, hovercraft, aircrafts (CISG, art. 2.), which are also mostly bought online by individual customers rather than businesses. CISG may be applied to e-commerce contracts involving both the manufacture or production and sale of goods (CISG, art. 3(1)). Yet, CISG does not apply to contracts whose main part is the supply of labour or other services (CISG, art. 3(2)). Thus, it could be noted that CISG cannot apply to e-commerce contracts involving the supply of online services or, subject to special analysis in a case by case basis, the transfer of digital products or services. As e-commerce allows businesses to have presence in multiple jurisdictions or just a 'web' presence, a basic question is: what would be the place of business for purposes of CISG rules? CISG, art. 10 says that when one a party has more than one place of business, the place of business, for purposes of CISG application, would be the place of business with the closest relationship to the contract and its performance' before the conclusion of the contract. Then, if the party does not have a place of business (e.i. Web presence'), the place of business is the habitual residency. CISG, art. 10(b). CISG does not say whose' habitual residency. Obviously, at the time this convention was drafted, they preconceived individual or corporate parties.' CISG, as most current legislations on e-commerce contracts, does not require any specific form for the contract to be valid; no writing is required. CISG, art. 11. This characteristic facilitates e-contracts accomplished through simple purchase orders or any other online form.

Some introductory remarks on the CISG [*]

Prof. Dr. Peter Huber, LL.M. (London), Mainz [...]

VII. Usages and trade practices 1. Practices and usages by consent 2. Relevant international trade usages 3. Specific issues

[...]

VII. USAGES AND TRADE PRACTICES

It is self-evident that trade usages and trade practices may play an important role in international sales contracts. Art. 9 CISG recognises this fact. In its two paragraphs

the provision distinguishes between two different methods of making usages or practices binding on the parties. 1. Practices and usages by consent Art. 9(1) CISG states that the parties are bound by any usage to which they have agreed and by any practices which they have established between themselves. In short, the provision states that the parties are bound by usages and practices to which they have agreed (explicitly, implicitly or by conduct).[80] The provision therefore specifically formulates what would result from the application of Art. 6 CISG and Art. 8 CISG anyway.[81] As the "incorporation" of the usages under Art. 9(1) CISG is in the last resort based on the consensus of the parties and -- unlike under Art. 9(1) CISG -- not on their "international recognition", it does not matter whether the usages are local, regional, national or international.[82] It is submitted that the formation of the consensus required by Art. 9(1) CISG should be assessed according to the rules of Art. 8, 14 ff. CISG or according to the general principles deriving from these provisions.[83] 2. Relevant international trade usages Art. 9(2) CISG goes somewhat farther. It essentially states that, unless otherwise agreed, relevant international trade usages (which are defined more closely as being widely known to and regularly observed by parties to contracts of the type involved in the particular trade concerned) will be binding on the parties [84] if they knew or ought to have known of these usages. The provision may give rise to difficult problems: In fact, if the usage is widely known in the relevant trade, most parties doing business in that area ought to have known of that usage. It is, however, conceivable that this may not be so in exceptional cases so that the requirement of "know or ought to have known" is not redundant.[85] A further question arises with regard to regionally limited usages. The predominant opinion seems to be that as a rule only those parties can be bound by [page 237] those usages which either are located in that geographical area or which are continuously doing business there.[86] It is submitted that this rule will in most cases be correct, but that one should not "invent" a specific requirement in that respect. In fact, this rule will usually simply flow from the requirement that the usage must be recognised in the "particular trade" and from the requirement that the parties "knew or ought to have known" it. 3. Specific issues Whether a usage exists in the relevant trade and whether it is widely accepted will usually be a question of fact, not of law.[87] The burden of proof for the existence of the usage should be placed on the party that relies on it.[88]

The "validity" of any usages that may be relevant is not governed by the CISG. This is clearly stated by Art. 4 lit. (a) CISG. The validity will therefore be a matter for the applicable domestic law (as determined by the private international law of the forum).[89] It is submitted, however, that validity problems will rarely arise with regard to trade usages; an example for such an issue is the case where the usage infringes mandatory rules of the applicable domestic law.[90] It should further be noted that as mentioned above -- the formation of the consensus that is required under Art. 9(1) CISG is not covered by the validity exception. If there is a binding usage or practice in the sense of Art. 9 CISG, it will usually take precedence over the provisions of the Convention.[91] It is further submitted that a usage or practice binding under Art. 9(1) CISG will usually take precedence over a usage binding under Art. 9(2) CISG as that provision explicitly states that it is subject to the parties' agreeing "otherwise".[92] For the same reason one should normally assume that usages or practices should give way to conflicting terms in the contract.[93] Several legal systems know a rule or a trade usage that silence as a response to commercial letters of confirmation (purporting to confirm the content of oral agreements) amounts to an acceptance of the content of those letters. The CISG does not contain such a rule. It is further submitted that one cannot find a general principle (Art. 7(2) CISG) to that effect as the basic rule under the CISG is that silence in itself does not amount to an acceptance (Art. 18(1) CISG). In the author's opinion therefore, any usage that may exist in certain countries, regions or branches can only become relevant under the CISG by virtue of Art. 9 CISG.[94] In the case of Art. 9(2) CISG, this will usually require that the relevant usage is known both where the seller and where the buyer have their place of business (or continuously do business),[95] as mentioned above (b). Another issue arises where the parties used a trade term from the INCOTERMS without however explicitly referring to the INCOTERMS (e.g.: "CIF Rotterdam" instead of "CIF Rotterdam (INCOTERMS 2000)". It has been held in case law that as a rule such a clause should be construed as referring to the INCOTERMS.[96] This view has been criticised for not taking into account that national legal systems may ascribe different meanings to those terms than the INCOTERMS do.[97] It is submitted that the solution to this problem should be found by adhering to the rules of Art. 9 CISG. The applicability of the INCOTERMS in such cases would therefore depend either on the kind of "consensus" meant in Art. 9(1) CISG or on the requirements of Art. 9(2) CISG. The same principles should apply when considering whether the UNIDROIT Principles of International Commercial Contracts can be regarded as usages in the

sense of Art. 9 CISG. The answer will therefore have to be found on a case-by-case basis.[98] [page 238] Go to full text of commentary by Huber FOOTNOTES * The present article is based on the introductory chapter of Peter Huber / Alastair Mullis, The CISG -- A new textbook for students and practitioners, which will be published by Sellier, European Law Publishers in spring 2007. [...] 80. See Ferrari, in: Ferrari / Fletchner / Brand, The Draft Digest and Beyond, p. 192. 81. Schmidt-Kessel, in: Schlechtriem / Schwenzer, Commentary, Art. 9 Nr. l. 82. Ferrari, in: Ferrari / Fletchner / Brand, The Draft Digest and Beyond, p.194; Schmidt-Kessel, in: Schlechtriem / Schwenzer, Commentary, Art. 9 Nr. 6; see also (Austrian) Oberster Gerichtshof, 15 October 1998 and 9 March 2000, <http://www.cisg-online.ch> Nr. 380 and Nr. 573. 83. Schmidt-Kessel, in: Schlechtriem / Schwenzer, Commentary, Art. 9 Nr. 7. 84. The provision uses a fiction: The parties are considered to have these usages impliedly made applicable to their contract or its formation. 85. Ferrari, in: Ferrari / Fletchner / Brand, The Draft Digest and Beyond, p, 201. 86. See (Austrian) Oberster Gerichtshof, 21 March 2000, <http://www.cisg-online.ch> Nr. 641; Ferrari, in: Ferrari / Fletchner / Brand, The Draft Digest and Beyond, p. 201 with further references. 87. See (Austrian) Oberster Gerichtshof, 21 March 2000, <http://www.cisg-online.ch> Nr. 641; (German) Oberlandesgericht Dresden, 9 July 1998, <http://www.cisgonline.ch> Nr. 559. 88. (German) Oberlandesgericht Dresden, 9 July 1998, <http://www.cisg-online.ch> Nr. 559; Schmidt-Kessel, in: Schlechtriem / Schwenzer, Commentary, Art. 9 Nr. 20; Ferrari, in: Ferrari / Fletchner / Brand, The Draft Digest and Beyond, p. 204 f.

89. For more detail see Ferrari, in: Ferrari / Fletchner / Brand, The Draft Digest and Beyond, p. 194 f., pointing out that this may also be the law applicable to a trade center which has such usages (e.g. a seaport or an exchange). 90. Schlechtriem, in: Schlechtriem / Schwenzer, Commentary, Art. 4 Nr. 16. 91. (Austrian) Oberster Gerichtshof, 21 March 2000, <http://www.cisg-online.ch> Nr. 641; Ferrari, in: Ferrari / Fletchner / Brand, The Draft Digest and Beyond, p. 197, 199. 92. Ferrari, in: Ferrari / Fletchner / Brand, The Draft Digest and Beyond, p. 199, where he furthermore discusses the interesting case that two usages which are binding under Art. 9(2) CISG lead to conflicting results and submits that the usage which is more closely connected to the contractual relationship should take precedence; but see for a different opinion in that respect (the usages cancelling each other out): Bonell in: Bianca / Bonell, Commentary on the International Sales Law, The 1980 Vienna Sales Convention (1987), Art. 9 Nr. 2.2. 93. (German) Oberlandesgericht Saarbrcken, 13 January 1993, <http://www.cisgonline.ch> Nr. 83; Ferrari, in: Ferrari / Fletchner / Brand, The Draft Digest and Beyond, p. 199. 94. (German) Oberlandesgericht Frankfurt, 5 July 1995, <http://www.cisg-online.ch> Nr. 258; see also (Swiss) Zivilgericht Basel-Stadt, 21 December 1992, <http://www.cisg-online.ch> Nr. 55 which regarded the requirements of Art. 9 CISG as fulfilled in the case at hand. 95. See (German) Oberlandesgericht Frankfurt, 5 July 1995, <http://www.cisgonline.ch> Nr. 258. 96. U.S. District Court, Southern District of New York, 26 March 2002, <http://www.cisg-online.ch> Nr. 615 ("St. Paul Guardian Insurance Company and Travelers Insurance Company, as subrogees of Shared Imaging, Inc. VS. Neuromed Medical Systems & Support, GmbH, et al."); (Italian) Corte di Appello di Genova, 24 March 1995, <http://www.cisg-online.ch> Nr. 315; Arbitral Award, Tribunal of International Commercial Arbitration at the Russian Federation Chamber of Commerce and Industry, 6 June 2000, <http://www.cisg-online.ch> Nr. 1249. 97. Ferrari, in: Ferrari / Fletchner / Brand, The Draft Digest and Beyond, p. 203. 98. Ferrari, in: Ferrari / Fletchner / Brand, The Draft Digest and Beyond, p. 204.

The United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG) has been recognized as the most successful attempt to unify a broad area of commercial law at the international level. The self-executing treaty aims to reduce obstacles to international trade, particularly those associated with choice of law issues, by creating even-handed and modern substantive rules governing the rights and obligations of parties to international sales contracts. At the time this is written (February 2009), the CISG has attracted more than 70 Contracting States that account for well over two thirds of international trade in goods, and that represent extraordinary economic, geographic and cultural diversity. The CISG is a project of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL), which in the early 1970s undertook to create a successor to two substantive international sales treaties Convention relating to a Uniform Law on the Formation of Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (ULF) and the Convention relating to a Uniform Law for the International Sale of Goods (ULIS) both of which were sponsored by the International Institute for the Unification of Private Law (UNIDROIT). The goal of UNCITRAL was to create a Convention that would attract increased participation in uniform international sales rules. The text of the CISG was finalized and approved in the six official languages of the United Nations at the United Nations Conference on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, held in 1980, in Vienna. The CISG entered into force in eleven initial Contracting States on 1 January 1988, and since that time has steadily and continuously attracted a diverse group of adherents. The CISG governs international sales contracts if (1) both parties are located in Contracting States, or (2) private international law leads to the application of the law of a Contracting State (although, as permitted by the CISG (article 95), several Contracting States have declared that they are not bound by the latter ground). The autonomy of the parties to international sales contracts is a fundamental theme of the Convention: the parties can, by agreement, derogate from virtually any CISG rule, or can exclude the applicability of the CISG entirely in favor of other law. When the Convention applies, it does not govern every issue that can arise from an international sales contract: for example, issues concerning the validity of the contract or the effect of the contract on the property in (ownership of) the goods sold are, as expressly provided in the CISG, beyond the scope of the Convention, and are left to the law applicable by virtue of the rules of private international law (article 4). Questions concerning matters governed by the Convention but that are not expressly addressed therein are to be settled in conformity with the general principles of the CISG or, in the absence of such principles, by reference to the law applicable under the rules of private international law. Among the many significant provisions of the CISG are those addressing the following matters: Interpretation of the parties agreement; The role of practices established between the parties, and of international usages; The features, duration and revocability of offers; The manner, timing and effectiveness of acceptances of offers; The effect of attempts to add or change terms in an acceptance; Modifications to international sales contracts; The sellers obligations with respect to the quality of the goods as well as the time and place for delivery; The place and date for payment;

The buyers obligations to take delivery, to examine delivered goods, and to give notice of any claimed lack of conformity; The buyers remedies for breach of contract by the seller, including rights to demand delivery, to require repair or replacement of non-conforming goods, to avoid the contract, to recover damages, and to reduce the price for nonconforming goods; The sellers remedies for breach of contract by the buyer, including rights to require the buyer to take delivery and/or pay the price, to avoid the contract, and to recover damages; Passing of risk in the goods sold; Anticipatory breach of contract; Recovery of interest on sums in arrears; Exemption from liability for failure to perform, including force majeure; Obligations to preserve goods that are to be sent or returned to the other party. The CISG also includes a provision eliminating written-form requirements for international sales contracts within its scope although the Convention authorizes Contracting States to reserve out of this provision, and a number have done so. The CISG also includes Final Provisions addressing such matters as ratification, acceptance, approval and accession; the interplay between the CISG and other overlapping international agreements; declarations and reservations; entry-into-force dates; and denunciation of the Convention. Several other UNCITRAL projects are designed to work in tandem with the CISG. For example, the United Nations Convention on the Limitation Period in the International Sale of Goods contains rules governing the limitation period for claims arising under international sales contracts. The Limitations Convention was originally promulgated in 1974, but was amended in 1980 by a Protocol adopted by the Diplomatic Conference that approved the CISG in order to harmonize the two Conventions. At the time this is written, the amended Limitations Convention is in force in 20 Contracting States. In 2005, the General Assembly adopted the United Nations Convention on the Use of Electronic Communications in International Contracts to address various issues arising when electronic communications methods are employed in connection with international contracts, including international sales contracts. Issues addressed in the Electronic Communications Convention include contract formation by automated communications, the time and place that electronic communications are deemed dispatched and received, determination of the location of parties employing electronic communications, and criteria for establishing functional equivalence between electronic and hard copy communication and authentication. At the time this is written, 18 States have signed the Electronic Communications Convention, although it has not yet been ratified or acceded to by any State and it has not yet entered into force. No special tribunals were created for the CISG; it is applied and interpreted by the national courts and arbitration panels that have jurisdiction in disputes over transactions governed by the Convention. To achieve its fundamental purpose of providing uniform rules for international sales, the Convention itself requires that it be interpreted with a view to maintaining its international character and uniformity. To that end, special research resources, often consisting of databases available free of charge through the Internet, provide access to materials designed to foster uniform international understanding of the rules of the CISG. These resources, including several developed and maintained by UNCITRAL in the six official languages of the United Nations, allow access to court and arbitral decisions applying the CISG from around the world, the travaux prparatoires of the CISG, and commentary on the Convention by a global community of scholars. Related A. Legal Materials Instruments

Convention relating to a Uniform Law on the International Sale of Goods, The Hague, 1 July 1964, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 834, p. 107. Convention relating to a Uniform Law on the Formation of Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, The Hague,

July

1964,

United

Nations, Treaty

Series,

vol.

834,

p.

169.

Convention on the Limitation Period in the International Sale of Goods, New York, 14 June 1974, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1511, p. 3. Protocol amending the Convention on the Limitation Period in the International Sale of Goods, Vienna, 11 April 1980, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1511, p. 77. Convention on the Limitation Period in the International Sale of Goods, as amended by the Protocol of 11 April 1980, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1511, p. 99. United Nations Convention on the Use of Electronic Communications in International Contracts, New York, 23 November 2005 (General Assembly resolution 60/21 of 23 November 2005). B. Documents

Final Act of the United Nations Conference on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, 10 March 11 April l980 (A/CONF.97/18). Commentary on the Draft Convention on Contracts for the International Sales of Goods, prepared by the Secretariat (A/CONF.97/5). UNCITRAL, Digest of Case Law on the United Nations Convention on the International Sales of Goods 2008 revision. [For other documents relating to the travaux prparatoire of the CISG, see the UNICTRAL website.] C. Doctrine

Commentary on the UN Convention on the International Sale of Goods (CISG) (Peter Schlechtriem & Ingeborg Schwenzer, eds.) 2nd (English) ed., Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005 (English-version of the 4th edition of Kommentar zum Einheitlichen UN-Kaufrecht). J. O. Honnold, Uniform Law for International Sales under the 1980 United Nations Convention, 3rd ed., The Hague: Kluwer Law International, 1999 (4th ed. forthcoming in 2009). [For other recommended sources, see the Related Material accompanying the lectures on the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods in the Lecture Series portion of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law.]

[top]

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- 08 Evidence - Burden of Proof and Presumptions - UM CLEDocument25 pages08 Evidence - Burden of Proof and Presumptions - UM CLEMelanie Joy Camarillo YsulatNo ratings yet

- 08 Evidence - Burden of Proof and Presumptions - UM CLEDocument25 pages08 Evidence - Burden of Proof and Presumptions - UM CLEMelanie Joy Camarillo YsulatNo ratings yet

- Evidence Rules and PrinciplesDocument37 pagesEvidence Rules and Principlesdaboy15No ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Labor Relation NotesDocument7 pagesLabor Relation NotesMelanie Joy Camarillo YsulatNo ratings yet

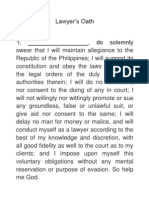

- Lawyer's OathDocument1 pageLawyer's OathKukoy PaktoyNo ratings yet

- PropertyCases Art427Document93 pagesPropertyCases Art427Melanie Joy Camarillo YsulatNo ratings yet

- Overview of Uncitral Conciliation and Arbitration RulesDocument2 pagesOverview of Uncitral Conciliation and Arbitration RulesMelanie Joy Camarillo YsulatNo ratings yet

- A. Scope of ApplicationDocument6 pagesA. Scope of ApplicationMelanie Joy Camarillo YsulatNo ratings yet

- A M No 07-11-08-SC (Special Rules On ADR)Document50 pagesA M No 07-11-08-SC (Special Rules On ADR)Neal BaintoNo ratings yet

- EcccDocument35 pagesEcccMelanie Joy Camarillo YsulatNo ratings yet

- PrelimDocument17 pagesPrelimMelanie Joy Camarillo YsulatNo ratings yet

- PropertyCases Art427Document93 pagesPropertyCases Art427Melanie Joy Camarillo YsulatNo ratings yet

- Gsis Case1Document24 pagesGsis Case1Twinkle YsulatNo ratings yet

- Case Digest On Property LawDocument8 pagesCase Digest On Property LawMelanie Joy Camarillo YsulatNo ratings yet

- IbtprefiDocument15 pagesIbtprefiMelanie Joy Camarillo YsulatNo ratings yet

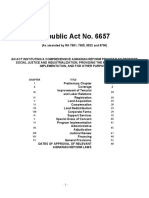

- Ra 6657Document60 pagesRa 6657Sam AjocNo ratings yet

- The People of The Philippines,, Napoleon M, PacabesDocument2 pagesThe People of The Philippines,, Napoleon M, PacabesMelanie Joy Camarillo YsulatNo ratings yet

- IbtprefiDocument15 pagesIbtprefiMelanie Joy Camarillo YsulatNo ratings yet

- Be It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledDocument46 pagesBe It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledMelanie Joy Camarillo YsulatNo ratings yet

- RA 8187 Paternity Leave ActDocument1 pageRA 8187 Paternity Leave ActBreth1979No ratings yet

- REPUBLIC ACT 8972 (Solo Parents' Welfare Act of 2000)Document5 pagesREPUBLIC ACT 8972 (Solo Parents' Welfare Act of 2000)Wilchie Dane OlayresNo ratings yet

- CasesDocument27 pagesCasesMelanie Joy Camarillo YsulatNo ratings yet

- RP Vs CA Et AlDocument2 pagesRP Vs CA Et AlMelanie Joy Camarillo YsulatNo ratings yet

- Sexual Harassment SoclegDocument8 pagesSexual Harassment SoclegMelanie Joy Camarillo YsulatNo ratings yet

- Gsis Case1Document24 pagesGsis Case1Twinkle YsulatNo ratings yet

- Be It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledDocument46 pagesBe It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledMelanie Joy Camarillo YsulatNo ratings yet

- Republic of the Philippines passes anti-sexual harassment lawDocument3 pagesRepublic of the Philippines passes anti-sexual harassment lawErika Jane Madriago PurificacionNo ratings yet

- The People of The Philippines,, Napoleon M, PacabesDocument2 pagesThe People of The Philippines,, Napoleon M, PacabesMelanie Joy Camarillo YsulatNo ratings yet

- EvidenceDocument9 pagesEvidenceMelanie Joy Camarillo YsulatNo ratings yet