Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Historia Diseño Grafico MIT

Uploaded by

Alex RosadoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Historia Diseño Grafico MIT

Uploaded by

Alex RosadoCopyright:

Available Formats

Graphic Design History: Past, Present, and Future Teal Triggs

Graphic design, it seems, is still searching for its past. Other design disciplines, such as fashion and industrial design, have an established tradition of archiving, documenting, critically writing, and publishing history, as well as engaging with social, cultural, and political contexts. Such histories have, for example, focused on the study of designed objects as well as design movements; celebrated named designers and the professions history; and explored design in relationship to other areas, such as material culture. This is not to say that graphic design has not had its share of commentators who have been defining approaches to studying its own history. 1 However, there remains a sense that graphic design history is less established as a discipline, and perhaps less exploratory in terms of defining new ways of writing about this history. The intent of this collection is to look again at the issues surrounding how we might define graphic design history, as well as to propose new ways forward. The first conference to bring together academics, educators, and design practitioners on a formal platform was The First Symposium on the History of Graphic Design: Coming of Age, held at the Rochester Institute of Technology in 1983. Organizers Barbara Hodik and Roger Remington wrote that up to this point, the history of graphic design has been scattered among the pasts of art, printing, typography, photography, and advertising.2 The remit of the symposium was to share information, but also to recognize the need for pausing and taking stock of the events, forces, and individuals that contributed to what we now know as graphic design.3 Part of this reflection was to acknowledge the need to move away from art history and recognize a design history that took into account other disciplines, such as sociology, anthropology, aesthetics, politics, economics.4 This move also extended into highlighting the need for a distinct graphic design criticism to express applied ideas.5 Other conferences followed, specifically focusing on graphic design history, including Steven Heller and Richard Wildes successful ten-year series, Modernism and Eclecticism: A History of American Graphic Design (1990s) under the School of Visual Arts. Heller also organized How We Learn What We Learn (1997), the proceedings from which formed the foundation of his edited book, The Education of a Graphic Designer, and subsequent publications in the specialist areas of illustration, typography, and e-design.

2010 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Design Issues: Volume 27, Number 1 Winter 2011 3

3 4

The past few years have seen an invigorating plethora of textbooks designed primarily for an undergraduate readership, which take as their starting point the idea that history can be told as a narrative. Phrases from some of the books titles provide a clue as to their authorial viewpoint: The Story of (Cramsie, 2010); A Critical Guide (Drucker and McVarish, 2009); A New History (Eskilson, 2007); From Antiquity to the Present (Jubert, 2006). These tomes join the bookshelf with the wellworn pages of graphic design historys earlier benchmarks: A Concise History (Hollis, 1994) and A History of (Meggs, 1983). Such accounts inevitably raise questions about whose history? and written by whom?. Barbara Hodik and Roger Remington, The First Symposium on the History of Graphic Design: The Coming of Age (Rochester Institute of Technology, 1983), 5. Ibid. Victor Margolin, The Scope and Methodology of Design History, in Barbara Hodik and Roger Remington, The First Symposium on the History of Graphic Design: The Coming of Age (Rochester Institute of Technology, 1983), 26. Summary and Future Projections, in Barbara Hodik and Roger Remington, The First Symposium on the History of Graphic Design: The Coming of Age (Rochester Institute of Technology, 1983), 57.

Teal Triggs and Kerry Purcell, Introduction, New Views: Repositioning Graphic Design History, London College of Communication, (2005), 3. Alice Tremlow,End of history? Graphic design hasnt started, Eye 59 (Spring 2006): 80. Ralph Caplan, Why Graphic Design History, paper abstract in Modernism and Ecclecticism: A History of American Graphic Design (New York: School of Visual Arts, n.d.), n.p. Steven Heller, Epilogue: Interview with Louis Danziger in Steven Heller and Georgette Balance (eds) Graphic Design History (New York: Allworth Press, 2001), 329. 4

Graphic design was once again discussed in terms of distinct parts rather than as a coherent whole. In 2005, New Views: Repositioning Graphic Design History, was held at the London College of Communication. This event proposed to look beyond the familiar assortment of critical biographies, historical narratives, and anthologised readers in order to review and question conventional histories and design practices.6 One reviewer remarked that it is impossible to reposition graphic design history without knowing the original position in the first place.7 This statement may have been true in part, but the conference was successful in exploring whose history is it? with papers about the richness of graphic design history in countries such as Germany, Greece, India, Iran, and Mexico. Identifying a need for a graphic design history has a history itself and has been clearly articulated in texts by noted writers and designers, including Steven Heller, Andrew Blauvelt, and Victor Margolin. Others, including Ralph Caplan, have proposed we should be writing about the history of graphic design as a history of ideas as a way of broadening out the subject to include a wider context.8 Despite attempts to raise the level of debate, graphic design history seems strangely elusive in forging a place for itself among the stalwarts of academy and within publishing houses. A point of view that design critic Rick Poynor supported in his keynote during the New Views symposium. The phenomenon of the practitioner-historian is part of this discussion. In an interview with Steven Heller, Louis Danziger is credited as one of the first designers to teach a course in Graphic Design History at CalArts in c.1972 - although Danziger is quick to acknowledge that another designer Keith Goddard established the course a year earlier.9 More recently, practitioner-historians including Lorraine Wild, Michael Rock, Ellen Lupton, Joanna Drucker, Denise Gonzales Crisp and Kenneth Fitzgerald have played a significant role in helping to establish what a graphic design history might be through their own writings and teachings on the subject. Steven McCarthy elaborates on the point about an inherent tension that exists between the academic-historian and the practitionerhistorian and the ways in which such positions might affect any writing about graphic design history. In his essay, Designer-Authored Histories: Graphic Design at the Goldstein Museum of Design, McCarthy presents a selection of case studies from the museums publishing collection, including early twentieth- century design classics, Production Manager (PM, 19341942), Portfolio (19501951), and Dot Zero (19661968). He also features later publications, such as Octavo (19861992), Zed (19942000), and News of the Whirled (1997), in which designers also took on the role of editor. This interconnectedness between author, designer, and editor makes these and other similar publications significant in how they might lead a critique about the very world in which their commercial practice resides.

Design Issues: Volume 27, Number 1 Winter 2011

10 Kate Wells, Edgard Sienaert, and Joan Conolly, The Siyazama Project: A Traditional Beadwork and AIDS Intervention Program, Design Issues 20:2 (Spring 2004): 7389.

Designer-authored histories also play a role in forming a canon of graphic design history. Hilary Kenna, a PhD student at the University of the Arts London, takes as her starting point Emil Ruders book, Typographie: A Manual for Design (1967), which has long been an established part of the key literature on basic design principles. In her essay, Emil Ruder: A Future for Design Principles in Screen Typography, Kenna asks: how might history affect graphic design practice and our understanding of critical design principles as designers move from print to screen-based activities. Emil Ruders approach becomes central to her own practice-led research process, offering both a means to learning the rules and to breaking them as she strives for innovation in typographic screen-based experiments. At the same time, Robert Harland argues that, as a practitioner-turned-educator, the diagrammatic representation of graphic design will help us better understand the subjects plural domains. In his essay, The Dimensions of Graphic Design and Its Sphere of Influence, Harland assesses the positioning of graphic design history and theory in relationship to new ways of thinking about graphic design more generally. Graphic design must now be equally thought of as a tool for social as well as economic development and its history understood not necessarily as solely the domain of studying objects of graphic design. This brings us back to the question of the canon and whose history. The last two case studies included in this collection, which can be differentiated from the more polemical content, begin to address the challenges faced by historians today. Identifying a starting point for any graphic design history is problematic, and especially in cultures where oral-based traditions have been the basis of a system of communication. Piers Carey, in From the Outside In: A Place for Indigenous Graphic Traditions in Contemporary South African Graphic Design, argues for the inclusion of indigenous African graphic systems in any graphic design history of South Africa. At the same time, Carey recognizes the value of applying a historical understanding to the way graphic systems may be applied to contemporary communication challenges. This case study revisits the Siyazama Project, which raises awareness of HIV/ AIDS through traditional use of Zulu graphic symbols in beadwork (first examined in the Spring 2004 issue of Design Issues).10 Carey argues that designers and historians face a challenge as globalization increases and the inequality of cultural power is perpetuated. He calls for a graphic design history of South Africa to take note, not only of a history of Westernized graphic design, but equally of pre-colonial indigenous societies. On the other hand, Leong K. Chan takes as his starting point graphic design as a tool for national ideology and policy in Singapore and explores the notion of nation building through the governments policy of multi-racialism. In his case study,

Design Issues: Volume 27, Number 1 Winter 2011 5

11 Don Beer, Book Review: Past Futures. The Impossible Necessity of History (based on the Joanne Goodman Lectures), (review no.484) Reviews in History (accessed 3 October 2010) http:// www.history.ac.uk/reviews/review/484.

Visualising Multi-Racialism in Singapore: Graphic Design as a Tool for Ideology and Policy in Nation Building, one of several historical examples includes looking at late 1970s government campaigns, such as Speak Mandarin (1979), which attempted to secure, through the adoption of an appropriate visual language and narrative, an emphasis on unification, as well as on cultural identity. How might an understanding of history give us insights into the future building of nations and nationhood? But, what is the role of the graphic design historian? The prevalent view of the historian is of somebody who is meant to locate events in time and to provide an explanation as to why events happened when they did.11 They establish links between the present and the past and contribute to an understanding of design as it is currently practiced. I would argue that graphic design is in a unique position. While we need more trained design historians to provide a context to the understanding of graphic objects, movements, and people, we should also celebrate the practitionerhistorians who also have the capacity to locate, explain, and contribute to the development of graphic design practice. Graphic design history in the present is looking for its past; in doing so, it paves the way for the future of graphic design. Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincere thanks to the contributors for their insights into the history of graphic design, as well as to the editors of Design Issues who willingly provided a platform for us. Graphic design history is seen through the eyes not only of the historian, but also of the designer. I would like to thank Barnbrook design for contributing their perspective on the subject in this issues cover design.

Design Issues: Volume 27, Number 1 Winter 2011

You might also like

- TRIGS, Teal - Graphic Design HistoryDocument4 pagesTRIGS, Teal - Graphic Design HistoryRafael EfremNo ratings yet

- GJ VN Redundancy 1996Document7 pagesGJ VN Redundancy 1996tcircularNo ratings yet

- Research in Graphic Design2Document11 pagesResearch in Graphic Design2Kitti RókaNo ratings yet

- The Dimensions of Graphic Design and Its Spheres of InfluenceDocument14 pagesThe Dimensions of Graphic Design and Its Spheres of InfluencekenkothecatNo ratings yet

- Design Literacy: Understanding Graphic DesignFrom EverandDesign Literacy: Understanding Graphic DesignRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- CLARK BRODY JDH Current State Design HistoryDocument6 pagesCLARK BRODY JDH Current State Design HistorySuelen CaviquioloNo ratings yet

- WHITEHOUSE - The State of Design History As A DisciplineDocument18 pagesWHITEHOUSE - The State of Design History As A DisciplinelluettaNo ratings yet

- ACADEME AND DESIGN WRITING Changes in Design CriticismDocument7 pagesACADEME AND DESIGN WRITING Changes in Design CriticismmutableSNo ratings yet

- Bayazit (1999) Investigating Design A Review of Forty Years of Design ResearchDocument15 pagesBayazit (1999) Investigating Design A Review of Forty Years of Design ResearchMelissa PozattiNo ratings yet

- Investigating DesignedDocument14 pagesInvestigating DesignedJair RuedaNo ratings yet

- Oscar Person and Dirk Snelders: Brand Styles in Commercial DesignDocument13 pagesOscar Person and Dirk Snelders: Brand Styles in Commercial DesignVanesa Juarez100% (1)

- 40 Years DesignDocument4 pages40 Years DesignrobertoNo ratings yet

- Graphicdesignnewhistory JDHDocument4 pagesGraphicdesignnewhistory JDHmichel angeloNo ratings yet

- Reviews: Im 19. Jahihundert, Cari Hauer Veriag, Munich and ViennaDocument3 pagesReviews: Im 19. Jahihundert, Cari Hauer Veriag, Munich and ViennaWan Feisal Wan AliNo ratings yet

- Review of "100 Ideas That Changed Graphic Design": Cartography and Geographic Information Science January 2014Document5 pagesReview of "100 Ideas That Changed Graphic Design": Cartography and Geographic Information Science January 2014Bebhit KhanalNo ratings yet

- Looking Closer 4: Critical Writings on Graphic DesignFrom EverandLooking Closer 4: Critical Writings on Graphic DesignRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Visualizing Design History: An Analytical ApproachDocument19 pagesVisualizing Design History: An Analytical ApproachmonicaandinoNo ratings yet

- Graphic DesignDocument9 pagesGraphic DesignshuganeshNo ratings yet

- Designed To Improvethe Makings, Politics and Aesthetics ofDocument11 pagesDesigned To Improvethe Makings, Politics and Aesthetics ofสามชาย ศรีสันต์No ratings yet

- Frascara - Graphic Design - Fine Art or Social ScienceDocument13 pagesFrascara - Graphic Design - Fine Art or Social ScienceRicardo Cunha LimaNo ratings yet

- Dilnot 1 PDFDocument21 pagesDilnot 1 PDFMirela DuculescuNo ratings yet

- The State of Design History. Part IIDocument19 pagesThe State of Design History. Part IICamila PieschacónNo ratings yet

- Graphic Design: Fine Art or Social Science? Author(s) : Jorge Frascara Source: Design Issues, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Autumn, 1988), Pp. 18-29 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 26/06/2014 02:44Document13 pagesGraphic Design: Fine Art or Social Science? Author(s) : Jorge Frascara Source: Design Issues, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Autumn, 1988), Pp. 18-29 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 26/06/2014 02:44Khemmiga TeerapongNo ratings yet

- Urbandesign NOTES SubikDocument46 pagesUrbandesign NOTES SubikArbind MagarNo ratings yet

- Fiction in Design Research: Report On The 6th Swiss Design Network Conference in Basle, 2010Document5 pagesFiction in Design Research: Report On The 6th Swiss Design Network Conference in Basle, 2010eypmaNo ratings yet

- Civilian Design ThinkingDocument17 pagesCivilian Design ThinkingTazul IslamNo ratings yet

- Design Like You Give A Damn ArchitectureDocument4 pagesDesign Like You Give A Damn ArchitectureRodo GarciaNo ratings yet

- 4.130 ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN THEORY AND METHODS: THE AGENCY OF ARCHITECTURAL RESEARCH Researching The Export of American Architectural Research For The 2014 Venice BiennaleDocument5 pages4.130 ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN THEORY AND METHODS: THE AGENCY OF ARCHITECTURAL RESEARCH Researching The Export of American Architectural Research For The 2014 Venice BiennaleSudhanshu MandlikNo ratings yet

- Towards An Integrative Theory of Urban DesignDocument120 pagesTowards An Integrative Theory of Urban DesignMoureenNazirNo ratings yet

- 40 Years of Design Research Cross2007Document4 pages40 Years of Design Research Cross2007EquipoDeInvestigaciónChacabucoNo ratings yet

- Copying, Cutting and Pasting Social Spheres Computer Designers' Participation in Architectural ProjectsDocument17 pagesCopying, Cutting and Pasting Social Spheres Computer Designers' Participation in Architectural ProjectsnivindaoudNo ratings yet

- VIDLER, Anthony. Toward A Theory of The Architectural Program (2003)Document17 pagesVIDLER, Anthony. Toward A Theory of The Architectural Program (2003)Ninna FeijóNo ratings yet

- The Science of Urban DesignDocument11 pagesThe Science of Urban DesignTanya MNo ratings yet

- Draw Is MoreDocument7 pagesDraw Is Moreuntilted1212No ratings yet

- Design SpeakDocument5 pagesDesign SpeakwillacNo ratings yet

- Architectural Design ResearchDocument15 pagesArchitectural Design ResearchTri Joko DaryantoNo ratings yet

- Lectura Opcional Against Digital Art HistoryDocument10 pagesLectura Opcional Against Digital Art HistoryCarolina Del ValleNo ratings yet

- Modernism Thesis StatementDocument7 pagesModernism Thesis StatementHelpWithWritingPapersPittsburgh100% (2)

- Forms of Rockin': Graffiti Letters and Popular CultureFrom EverandForms of Rockin': Graffiti Letters and Popular CultureRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Material Thinking: The Aesthetic Philosophy of Jacques Rancière and The Design Art of Andrea ZittelDocument17 pagesMaterial Thinking: The Aesthetic Philosophy of Jacques Rancière and The Design Art of Andrea ZittelEduardo SouzaNo ratings yet

- Art History Dissertation Proposal ExampleDocument7 pagesArt History Dissertation Proposal Exampleprenadabtag1981100% (1)

- Graphic Design - TypographyDocument21 pagesGraphic Design - TypographyKapil SinghNo ratings yet

- Rule-Based Design, in Honour of Lionel MarchDocument4 pagesRule-Based Design, in Honour of Lionel MarchmocorohNo ratings yet

- Buchanan Design RhetoricDocument20 pagesBuchanan Design RhetoricxtinelusNo ratings yet

- Design Like You Give A Damn ReviewDocument4 pagesDesign Like You Give A Damn ReviewTânia Fernandes0% (1)

- Ahrentzen Space Between The Studs1Document29 pagesAhrentzen Space Between The Studs1Silvia ScoralichNo ratings yet

- ESCOBAR - Notes-on-the-Ontology-of-Design-Parts-I-II - III - Arturo Escobar PDFDocument85 pagesESCOBAR - Notes-on-the-Ontology-of-Design-Parts-I-II - III - Arturo Escobar PDFDany PereiraNo ratings yet

- Dimensions of ParticipationDocument18 pagesDimensions of Participationfabianoramos.educNo ratings yet

- Visualizing Temporal Patterns in Visual MediaDocument23 pagesVisualizing Temporal Patterns in Visual MediacholoNo ratings yet

- Cheryl Buckley: Made in Patriarchy II: Researching (Or Re-Searching) Women and DesignDocument12 pagesCheryl Buckley: Made in Patriarchy II: Researching (Or Re-Searching) Women and DesignPaloma VelázquezNo ratings yet

- Artigo - Digital Art HistoryDocument6 pagesArtigo - Digital Art HistoryRafael Iwamoto TosiNo ratings yet

- Generative Methods in Urban Design: A Progress Assessment: Journal of UrbanismDocument20 pagesGenerative Methods in Urban Design: A Progress Assessment: Journal of UrbanismMera ViNo ratings yet

- Histories of Design Pedagogy Virtual SpeDocument24 pagesHistories of Design Pedagogy Virtual SpeCarlos GuerraNo ratings yet

- Book Review: Explorations in Urban Design: An Urban Design Research PrimerDocument12 pagesBook Review: Explorations in Urban Design: An Urban Design Research PrimerBushra daruwalaNo ratings yet

- Investigating Design A Review of Forty Years of Design ResearchDocument24 pagesInvestigating Design A Review of Forty Years of Design ResearchNVPNo ratings yet

- Generative Methods in Urban Design: A Progress AssessmentDocument21 pagesGenerative Methods in Urban Design: A Progress AssessmentSadia AmmarNo ratings yet

- Designerly Ways of Knowing Nigel CrossDocument8 pagesDesignerly Ways of Knowing Nigel CrossbomberstudiosNo ratings yet

- Appendix A: CTS Exam Content Outline: Domains/Tasks % of Exam # of Items Domain A: Creating AV Solutions 61% 61Document9 pagesAppendix A: CTS Exam Content Outline: Domains/Tasks % of Exam # of Items Domain A: Creating AV Solutions 61% 61Alex RosadoNo ratings yet

- CTS Candidate Handbook: Certified Technology SpecialistDocument7 pagesCTS Candidate Handbook: Certified Technology SpecialistAlex RosadoNo ratings yet

- RGS 7.5.0 User GuideDocument103 pagesRGS 7.5.0 User GuideAlex RosadoNo ratings yet

- RGS 7.5.0 User GuideDocument103 pagesRGS 7.5.0 User GuideAlex RosadoNo ratings yet

- Altair 4 B ManualDocument5 pagesAltair 4 B ManualdunenuNo ratings yet

- Hap Encoding TipsDocument3 pagesHap Encoding TipsAlex RosadoNo ratings yet

- Orlan Stelarc and The Art of Virtual BodyDocument11 pagesOrlan Stelarc and The Art of Virtual BodyAlex RosadoNo ratings yet

- QuickInstallGuide UKDocument20 pagesQuickInstallGuide UKAlex RosadoNo ratings yet

- LedEdit Operating Manual PDFDocument21 pagesLedEdit Operating Manual PDFHoria GeorgescuNo ratings yet

- Orlan Stelarc and The Art of Virtual BodyDocument11 pagesOrlan Stelarc and The Art of Virtual BodyAlex RosadoNo ratings yet

- Helen - The Power of JudgementDocument4 pagesHelen - The Power of JudgementAlex RosadoNo ratings yet

- Fluidos Con ProcessingDocument17 pagesFluidos Con ProcessingAlex RosadoNo ratings yet

- DietrichDocument4 pagesDietrichAlex RosadoNo ratings yet

- What Is Postphenomenology ?Document0 pagesWhat Is Postphenomenology ?Alex RosadoNo ratings yet

- Fluxus: Scheme Livecoding: Dave GriffithsDocument38 pagesFluxus: Scheme Livecoding: Dave GriffithsAlex RosadoNo ratings yet

- Desi 2009 25 4 91Document13 pagesDesi 2009 25 4 91Alex RosadoNo ratings yet

- Design Problems Kees Dorst MitDocument15 pagesDesign Problems Kees Dorst MitAlex RosadoNo ratings yet

- Consistent Multi-Device Design Using Device CategoriesDocument4 pagesConsistent Multi-Device Design Using Device CategoriesAlex RosadoNo ratings yet

- K30 Configuration Options v3 2Document1 pageK30 Configuration Options v3 2Alex RosadoNo ratings yet

- Ableton EULADocument5 pagesAbleton EULAhanna_twinzNo ratings yet

- Graphics Packages - ICT - Software - RevisionDocument7 pagesGraphics Packages - ICT - Software - Revisionsana saleemNo ratings yet

- Joel Vilas Boas PDFDocument5 pagesJoel Vilas Boas PDFAna Carolina LemosNo ratings yet

- Alletun's Tome of Knowledge v1.3Document68 pagesAlletun's Tome of Knowledge v1.3wermezNo ratings yet

- Mapeh 5Document9 pagesMapeh 5Diana Rose AcupeadoNo ratings yet

- Graphic Design by CalArtsDocument32 pagesGraphic Design by CalArtsVansh Chavda100% (2)

- Lal Kitab Vol 2 1952 CompressedDocument228 pagesLal Kitab Vol 2 1952 CompressedsunitaranpiseNo ratings yet

- Lefleat RomDocument162 pagesLefleat RomAld' Sanada SanNo ratings yet

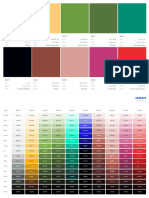

- Color 1 Color 2 Color 3 Color 4 Color 5: RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk NameDocument4 pagesColor 1 Color 2 Color 3 Color 4 Color 5: RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk NameValentina TorresNo ratings yet

- Eng 26Document26 pagesEng 26mbnikkiNo ratings yet

- Math4 LM U1Document89 pagesMath4 LM U1Ian UdaniNo ratings yet

- DLL - Mapeh-Arts 6 - Q3 - W3Document4 pagesDLL - Mapeh-Arts 6 - Q3 - W3Jesie EliasNo ratings yet

- Tutorial How To Write Bangla Using LaTeXDocument3 pagesTutorial How To Write Bangla Using LaTeXRubayyat HashmiNo ratings yet

- Brush Etching. Beguin.Document3 pagesBrush Etching. Beguin.Sandra CostabrasNo ratings yet

- Font Creator ManualDocument152 pagesFont Creator ManualkillnoNo ratings yet

- Colourising Using Photoshop: George ChilversDocument9 pagesColourising Using Photoshop: George ChilversphilipandrewhicksNo ratings yet

- Basic Designs: ©hitachi Construction Machinery Co., Ltd. 2009. All Rights ReservedDocument45 pagesBasic Designs: ©hitachi Construction Machinery Co., Ltd. 2009. All Rights ReservedPrudzNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Poster PreparationDocument2 pagesGuidelines For Poster PreparationHarjas SinghNo ratings yet

- C - PantoneDocument8 pagesC - PantoneMd Musfiqur RahmanNo ratings yet

- BS 4800Document16 pagesBS 4800Tarek helmyNo ratings yet

- Cajita CatrinaDocument3 pagesCajita Catrinapaolo umaña martinezNo ratings yet

- Bad Love Level 1 PDFDocument3 pagesBad Love Level 1 PDFFotos José RamónNo ratings yet

- Graphics Pipeline and GraphsDocument12 pagesGraphics Pipeline and GraphsRohit TiwariNo ratings yet

- 100 Cau Trac Nghiem Toan 7Document646 pages100 Cau Trac Nghiem Toan 7Dương TiễnNo ratings yet

- SBS Adding Trees in AllplanDocument8 pagesSBS Adding Trees in AllplanRusu LilianNo ratings yet

- The Other RGB Color ChartDocument5 pagesThe Other RGB Color Chartresolution8878No ratings yet

- Music I. Direction. Shade The Circle of Your Answer. A. Use The Musical Score To Answer Nos. 1-4Document7 pagesMusic I. Direction. Shade The Circle of Your Answer. A. Use The Musical Score To Answer Nos. 1-4ChristineNo ratings yet

- CG FileDocument37 pagesCG Filesimargrewal11No ratings yet

- Van Gogh Water Colour ENG PDFDocument1 pageVan Gogh Water Colour ENG PDFtesNo ratings yet

- Chapter 01 MCDocument5 pagesChapter 01 MCShahzad AshrafNo ratings yet