Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Legal Experts Letter To Gov. Brown

Uploaded by

Bjustb LoeweOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Legal Experts Letter To Gov. Brown

Uploaded by

Bjustb LoeweCopyright:

Available Formats

Governor Jerry Brown c/o State Capitol, Suite 1173 Sacramento, CA 95814 Re: Cautions Against Including Additional

Grounds for Enforcement of Detainer Requests in AB 4, the TRUST Act

Dear Governor Brown: We understand that your office may be considering amendments to the TRUST Act to authorize enforcement of immigration detainer requests for persons with prior removal orders and/or convictions for federal criminal immigration offenses of illegal entry (a misdemeanor) or reentry (a felony). We write to provide background on the defects in due process and substantive immigration law that can lead to unjust imposition of removal orders and illegal entry/reentry convictions, to explain that removal orders and illegal entry/reentry convictions have no relation to public safety, and to urge you not to include such factors as grounds to authorize immigration detainer enforcement in Californias TRUST Act. Prior removal orders and entry/reentry convictions all stem from an immigration system that is deeply flawed. Removal orders are routinely issued in abstentia, to noncitizens who did not receive notice of their removal hearings through no fault of their own. Even where a noncitizen receives notice of his or her hearing, many are unrepresented by counsel in proceedings lacking important procedural safeguards and there is inadequate relief from deportation in current U.S. immigration law, even for long-time residents of this country who have U.S. citizen children and spouses who depend on them. Similarly, as explained in detail below, illegal entry and reentry convictions are often obtained in circumstances that defy common American notions of due process and based on conduct that presents no threat or harm to public safety. Prior removal orders and entry/reentry convictions are all aspects of a persons record that canand often doexist without any violation of law other than unlawful presence or unlawful entry. Because each of these is the product of an unjust and unwise immigration system and none suggests a public safety basis for identifying or detaining an individual for law enforcement purposes, they should not form the basis for detainer enforcement in California.

Governor Jerry Brown August 12, 2013 Page 2

I.

Removal Orders Often Result from Serious Procedural Defects in the Immigration Court System. A. Individuals Are Frequently Ordered Removed In Abstentia.

The current immigration court system is backlogged and difficult to navigate. One of the consequences of this is the issuance of removal orders without hearings. In 2012, about 11% of removal orders were issued in absentia after people failed to appear to their immigration court hearings, and in previous years up to two-thirds of removal orders were issued without the participation of the person ordered deported.1 Some of the common reasons that people do not appear and therefore receive in absentia orders include not receiving a Notice to Appear (NTA) in immigration court at their correct address, receiving the NTA in a language they do not read, or not understanding the court proceedings.2 In addition, sometimes people are afraid of attending their hearing because, without an attorney to advise them of their options, they are fearful of what might happen. If noncitizens miss even one hearingeven if they are not even aware of the hearing or that they are in removal proceedingsthey are automatically ordered removed. For these reasons, prior removal orderswhich may have been issued with inadequate notice to the subject of the order and despite valid defenses to the chargesare unreliable. Moreover, they are indicative of civil immigration violations only, the enforcement of which should not be within the province of state and local law enforcement officers. B. Individuals Frequently Receive Stipulated Removal Orders. Stipulated removal occurs when someone signs their own order of removal before an ICE agent. A recent National Immigration Law Center (NILC) report found that individuals are often coerced into signing these orders of removal.3 Many do so without knowing that they may be eligible for some sort of relief from removal. The

U.S. Dep't of Justice, Executive Office for Immigration Review, FY 2012 Statistical Year Book, p. H1 (March 2013), available at http://www.justice.gov/eoir/statspub/fy12syb.pdf. Nina Bernstein, Old Deportation Orders Leading to Many Injustices, Critics Say, New York Times, February 19, 2004, http://www.nytimes.com/2004/02/19/nyregion/old-deportation-orders-leading-to-many-injusticescritics-say.html?src=pm (In 2004, the federal government estimated two-thirds of removal orders were issued in abstentia). 2 The Notice to Appear is the charging document in immigration court. 8 U.S.C. 1229(a). See e.g., Smykiene v. Holder, 707 F.3d 785 (7th Cir. 2013) (describing situation in which an individual was ordered removed in absentia after not receiving an NTA). 3 See Jennifer Lee Koh, et. al, Deportation without Due Process (Sept. 2011), National Immigration Law Center, available at http://www.nilc.org/2011sept8dwn.html. See also Jennifer Lee Koh,

1

Waiving Due Process (goodbye): Stipulated Orders of Removal and the Crisis in Immigration Adjudication, 91 N.C.L. Rev. 475 (2013).

Governor Jerry Brown August 12, 2013 Page 3

majority of the time, stipulated removal occurs before seeing an immigration judge and without the individual realizing that they have a right to see an immigration judge or receive immigration bond. C. The Immigration Court System Is Rife with Procedural Defects. Despite the severity of life-long deportation as a consequence, immigration courts provide many fewer procedural safeguards than are afforded defendants with even minor misdemeanor charges in Americas criminal courts. Some problems in immigration proceedings that lead to unfair results include: Appointed counsel is not available in removal proceedings and manyif not mostimmigrants face their charges without legal representation. The proliferation of immigration laws and regulations has aptly been called a labyrinth that only a lawyer could navigate, but the law does not require that the government provide legal representation (like the public defender system in criminal court) for immigrants facing deportation proceedings. Biwot v. Gonzalez, 403 F.3d 1094, 1098 (9th Cir. 2005). One study found that having representation is one of the two most important variables affecting the ability to secure a successful outcome in a case.4 Unfortunately, there is a crisis of both quantity and quality of immigration attorneys available to individuals facing deportation charges in recent years. Nearly half of all people who appeared in immigration court between 2008 and 2012 did not have legal representation.5 Because counsel is often a determinative factor in an immigrants ability to defend against charges in deportation proceedings, the current systemin which many, if not most, immigrants facing such charges lack legal representationleads to unfair results that should not be reproduced in Californias jails though detainer enforcement. With or without counsel, immigrants lack access to the records of their own cases and struggle to obtain copies of their files from the government. Although the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals has held that noncitizens facing charges in

New York Immigration Representation Study Report: Part 1, Accessing Justice: The Availability and Adequacy of Counsel in Removal Proceedings, 33 Cardozo L. Rev. 357, 363 (2011). Using a

4

sample from New York Immigration Court cases from October 2005 to December 24, 2010, this study found that 74% of individuals who are represented and released or never detained have successful outcomes whereas only 13% of individuals who are unrepresented and released or never detained have successful outcomes. 5 126,259 of the 289,934 people whose immigration court proceedings were completed in 2012 were unrepresented. U.S. Dept of Justice, Executive Office for Immigration Review, FY 2012 Statistical Year Book, G1 (Mar. 2013), http://www.justice.gov/eoir/statspub/fy12syb.pdf (stating that 45% were represented in FY 08, increasing to 56% in FY 12).

Governor Jerry Brown August 12, 2013 Page 4

immigration court must be given their immigration files as a matter of due process, in practice noncitizens are forced to obtain their records through Freedom of Information Act Requests, a process that can take months and effectively deny the litigants access to crucial information while their proceedings are pending.6 Immigration Courts Lack Resources Necessary to Provide Just and Consistent Outcomes. Immigration Courts lack many of the resources available to state and federal civil and criminal courts, including court reporters, bailiffs, and adequate translation services. Perhaps most striking is the crushing workload and lack of support endured by immigration judges, the consistency and quality of whose rulings are understandably affected. According to an American Bar Association report: The immigration courts have too few immigration judges and support staff, including law clerks, for the workload for which they are responsible. In 2008, immigration judges completed an average of 1,243 proceedings per judge and issued an average of 1,014 decisions per judge. To keep pace with these numbers, each judge would need to issue at least 19 decisions each week, or approximately four decisions per weekday. The shortage of immigration judges and law clerks has led to very heavy caseloads per judge and a lack of sufficient time for judges to properly consider the evidence and formulate well-reasoned opinions in each case.7

6 See Dent v. Holder, 627 F.3d 365 (9th Cir. 2010) (governments failure to provide noncitizen a copy of his alien file violated due process) and Hajro v. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, 832 F.

7

Reforming the Immigration System: Proposals to Promote Independence, Fairness, Efficiency, and Professionalism in the Adjudication of Removal Cases, American Bar Association Commission on

Supp. 2d 1095, 1108 (N.D. Cal. 2011) (finding that plaintiffs demonstrated a pattern and practice of failing to provide A-files to persons in a timely manner under the Freedom of Information Act).

Immigration, 2010 at ES-28. http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/migrated/media/nosearch/immigration_reform_executi ve_summary_012510.authcheckdam.pdf The same report noted troubling disparities in outcomes between immigration judges, whereby more than a quarter of immigration judges granted asylum or other relief to noncitizens that varied from the mean grant rate of judges in their home court by more than 50%. Id at ES-27.

Governor Jerry Brown August 12, 2013 Page 5

Immigration judges interviewed for a study on stress and burnout confirmed that the crushing workload they handle adversely impacts the quality of their decisions: We are denied transcripts and must decide complex cases, yet we are expected to render oral decisions on the spot. There is insufficient time in our schedules to provide for self-education and development in this complex area of the law. In those cases where I would like more time to consider all the facts and weigh what I have heard I rarely have much time to do so simply because of the pressure to complete cases. What is required to meet the case completions is quantity over quality.8

In this letter, we have only scratched the surface of the due process deficiencies in immigration court.9

8 Stuart L. Lustig, et al., Inside the Judges Chambers: narrative Responses from the National Association of Immigration Judges Stress and Burnout Study, 23 Geo. Immigr. L.J. 57 at 64-66, 72,

9

75 (2008) Additional areas of concern for the fairness of hearings are inadequate translation services, group hearings, and the growing use of videoconferencing for evidentiary hearings. Regarding subpar interpretation services, see, e.g., Lustig et al., supra note 8, at 67-68; Laura Abel, Language Access in Immigration Courts, Brennan Center for Justice, 1 (2011), http://www.brennancenter.org/sites/ default/files/legacy/Justice/LangAccess/Language_Access_in_Immigration_Courts.pdf ([T]here have been many incidents in which interpreters made mistakes and acted unprofessionally. This may be due in part to the Immigration Courts decision not to require their interpreters to obtain the rigorous certifications administered by either the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts or the state courts Consortium for Language Access in the Courts.); Appleseed, Assembly Line Injustice: Blueprint to Reform Americas Immigration Courts, 25 (May 2009), http://appleseednetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Assembly-Line-Injustice-Blueprint-toReform-Americas-Immigration-Courts1.pdf at 20 (As one interviewee told us, the perception is that if you cannot pass the federal court interpreter certification test, you become an Immigration Court interpreter.); Tony Rosado, Interpreting at the Immigration Court: Is It Really Headed for Disaster? The Professional Interpreter (Feb. 4, 2013), http://rpstranslations.wordpress.com/2013/02/ 04/interpreting-at-the-immigration-court-is-it-really-headed-for-disaster/ ([T]he reality is that when many interpreters think of immigration court the first thing that comes to mind is that it is in the hands of an agency that pays very little, demands minimum quality from its interpreters, takes a long time to pay, cancels assignments, and hires many of those interpreters who were not able to work anywhere else. I have worked in immigration court in different parts of the country and unfortunately, in some ways, this idea is not far from the truth.). While the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals has recognized due process concerns with group hearings, they are nevertheless permitted in the immigration context. See United States v. Nicholas-Armenta, 763 F.2d 1089, 1091 (9th Cir. 1985); United States v. Lopez-Vasquez, 1 F.3d 751, 754 (9th Cir. 1993) (per curiam) (Although we have held that the government may conduct group deportation hearings if the proceedings comport with due process, we have never held that due

Governor Jerry Brown August 12, 2013 Page 6

II.

There Is Inadequate Relief from Deportation in Current U.S. Immigration Law and Policy.

Even if every noncitizen had adequate notice of his hearing, were represented by adequate counsel, and appeared before an immigration judge with all necessary resources, current immigration law restricts the discretion that immigration judges have to provide relief from deportation to immigrants including long-term residents who pose no risk to public safety and who have significant ties to the community. In 1996, Congress added several grounds for deportation based on relatively minor criminal history. These grounds have been applied retroactively and mandatorily, making long-term lawful permanent residents subject to removal for offenses that were not grounds for removal at the time they were committed. Also in 1996, Congress eliminated forms of relief from deportation based on rehabilitation, ties to the community, and family relationships in the United States.10 Under current law,

process is satisfied by a mass silent waiver of the right to appeal . . . . Mass silent waiver creates a risk that individual detainees will feel coerced by the silence of their fellows. The immigration judges directive that to preserve the right to appeal a detainee must stand up so that I can talk to you about that did nothing to lessen this risk. Indeed, it tended to stigmatize detainees who wished to appeal and to convey a message that appeal was disfavored and contingent upon further discussion with the immigration judge. (internal citation omitted)); but see Animashaun v. INS, 990 F.2d 234, 238 (5th Cir. 1993) (concluding that there is no fundamental unfairness in the en mass nature of a deportation hearing). Videoconferencing, available in criminal trials for only limited purposes with a defendants consent, is widely used as a wholesale replacement for in-person proceedings within the immigration context without the immigrants consent. Note, Access to Courts and Videoconferencing in Immigration Court Proceedings, 122 Harv. L. Rev. 1181, 1182 (2009). See also Frank M. Walsh & Edward M. Walsh, Effective Processing or Assembly-Line Justice? The Use of Teleconferencing in Asylum Removal Proceedings, 22 Geo. Immigr. L.J. 259, 263 (2008). In addition to undermining an immigrants ability to communicate meaningfully with the immigration judge and convey his or her credibility in the proceedings, this practice forces an immigration attorney to choose between being able to consult confidentially with her client and maintaining a strong presence in the courtroom with an immigration judge and opposing counsel.

Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA) broadened the list of criminal convictions that would designate a non-citizen as an aggravated felon . . . . [C]ertain misdemeanor offenses under state law have been construed as aggravated felonies under the federal statute . . . . AEDPA specifically prevents immigration judges from allowing 212(c) waivers for any aggravated felons, not just those with at least five-year imprisonments, as was practiced previously. Without the ability to file a 212(c) waiver, a staggering amount of LPRs are facing mandatory removal proceedings for an increasingly wide array of relatively minor offenses. Immigration judges simply do not have the ability to provide any discretionary relief in such cases. Senator Edward Kennedy (D-MA) predicted the repercussions of these broad laws: An immigrant with an American citizen wife and children sentenced to one

See Human Rights Watch, Forced Apart: Families Separate and Immigrants Harmed by United States Deportation Policy, 5 (2007), http://www.hrw.org/reports/2007/us0707/us0707web.pdf; see also Note, Affording Discretion to Immigration Judges: A Comparison of Removal Proceedings in the United States and Canada, 32 B.C. Intl & Comp. L. Rev. 115, 121-22 (2009) (The Antiterrorism and

10

Governor Jerry Brown August 12, 2013 Page 7

a long-time undocumented family member of U.S. citizens cannot avoid deportation unless she is able to show exceptional and extremely unusual hardship to a U.S. citizen parent, child or spouse.11 Unfortunately, under this standard, a U.S. citizen childs hardship of growing up without a parent or outside of ones home country is not unusual enough to justify relief from deportation for any of the approximately 400,000 people deported every year under the current administration. As a result, enforcement of immigration detainers based on a prior order of removal alone may well lead to a life-long separation of family and devastation to family members left behind in the United States based solely on the unauthorized status of a parent who has no criminal record, who contributes meaningfully to our community, and who poses no threat of danger to persons or property. III. Illegal Entry and Reentry Convictions Are Obtained Through Procedures that Lack Due Process.

In recent years, prosecutions for unauthorized entry and reentry under 8 U.S.C. 1325 and 1326 have skyrocketed. In 2005, DHS and DOJ launched Operation Streamline, a fast-track prosecution effort for entry offenses in which federal magistrate judges (as opposed to district court judges) hold mass guilty plea hearings, where forty, fifty, or even a hundred defendants appear at one time. Prosecutions for illegal entry increased from 3,192 in 1992 to 48,032 in 2012, and as of March 2013, 22,526 people were incarcerated for immigration offenses in the federal prison system.12 Under Operation Streamline, a single federal public defender may represent dozens of defendants in one hearing. Many defendants meet with their defense attorney for only a few minutes, and multitudes of criminal cases are resolved in a single day.13 The short time frame does not allow defense attorneys to develop possible defenses such as derivative citizenship, asylum, or due process defects in a defendants underlying removal order, and 99% of Operation Streamline defendants

year of probation for minor tax evasion and fraud would be subject to this procedure. And under this provision, he would be treated the same as ax murderers and drug lords). 11 8 U.S.C. 1229b(b). 12 Human Rights Watch, Turning Migrants Into Criminals: The Harmful Impact of U.S. Border Prosecutions (May 2013), fig. 1 at 13 (based on data from the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), Syracuse Universtiy, TradFed Express Tool, http://tracfed.syr.edu/index/index.php?layer=cri; 73 (citing US Dept. of Justice, Federal Bureau of Prisons, Quick Facts About the Bureau of Prisons, last updated March 30, 2013. 13 Doug Keller, Rethinking Illegal Entry and Re-entry, 44 Loyola Univ. Chicago L.Rev 65 at 127 (2012).

Governor Jerry Brown August 12, 2013 Page 8

plead guilty.14 In its report on Operation Streamline, Human Rights Watch quotes Magistrate Judge Bernardo Velasco that the defense attorneys function merely as ushers on the conveyer belt to prison.15 Another magistrate judge, who estimates he has presided over 17,000 cases, described his role as a factory putting out a mold and commented that the U.S. government has created a felony class of noncitizens; he emphasized that where theres no criminal history, no immigration history, the criminalization of these defendants is something thats very difficult [for me].16 The Ninth Circuit has held that procedures used in these mass hearings violated important protections under the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure.17 Given the serious due process defects inherent in prosecution of entry-related immigration offenses, California should not use the conviction for such an offense as a basis to assist in immigration enforcement though an immigration detainer request. IV. Illegal Entry and Reentry Convictions Are the Result of Inhumane Immigration Policy.

The felony of illegal reentrymeaning unauthorized entry following a deportationmust be understood in the context of the deep procedural and substantive flaws in our immigration enforcement system set forth above. Human Rights Watch recently released a report based on data analysis and interviews with noncitizens, family members, judges, and federal defense attorneys regarding the circumstances leading to illegal entry and reentry convictions, including analysis of 73 individual cases.18 The report highlights two areas of human rights that are severely impacted by prosecution and sentencing of entry offenses: the right to asylum from persecution and the right to family unity. The draconian nature of current immigration lawa scheme that does not permit a judge to waive deportation based on family ties, rehabilitation and

14 Rethinking Illegal Entry and Re-entry at 115-16 (describing time-consuming research required for

derivative citizenship defense and collateral attacks on prior removal orders); Grassroots Leadership, Operation Streamline: Costs and Consequences at 14 (99% of defendants plead guilty). See also, Turning Migrants Into Criminals at 35 (Operation Streamlines name and exact prosecution policy varies from district to district, but all Streamline proceedings are fast and have predictable outcomes: a guilty pleas from virtually every defendant for misdemeanor illegal entry). 15 Turning Migrants into Criminals at 38. 16 Turning Migrants into Criminals at 35-36. 17 United States v. Roblero-Solis, 588 F.3d 692 (9th Cir. 2009) (judges failure to determine voluntariness of pleas individually for each defendant violated Rule 11, but objection was waived by defense counsel). 18 Turning Migrants into Criminals, supra n. 12.

Governor Jerry Brown August 12, 2013 Page 9

contributions to the communityis the direct cause for many, if not most, illegal reentry attempts. Human Rights Watch reported that defense attorneys in Los Angeles and San Diego estimated that 80 to 90 percent of their clients charged with illegal reentry have U.S. citizen family members. Similarly, Judge Robert Brack in Las Cruces, New Mexico estimated 30 to 40 percent of his cases involved people with US citizen family members: Its an everyday occurrence.19 Many of those prosecuted for reentry are undocumented, but were raised in this country; some are lawful permanent residents who are permanently barred from returning legally to this country after minor or old convictions. According to Magistrate Judge Philip Mesa, it is not unusual for reentry defendants to participate in their hearings without an interpreter, speaking English fluently.20 Many of those convicted of illegal entry or reentry have no other criminal history and represent no danger to public safety. Since illegal entry and illegal reentry are offenses stemming from an immigration system that is tearing apart the families of California by its failure to provide legal means for family members to stay together and are often based solely on unauthorized presence or entry, they do not serve any useful public safety interest of the state. Instead, including convictions for entry offenses as a justification for enforcement of immigration detainer requests by local sheriffs will undermine the TRUST Acts purpose and goal of limiting local participation in immigration enforcement and preserving community trust in police and sheriffs. We urge you not to suggest any amendments to the TRUST Act that would use federal entry offenses or prior removal orders as a basis for local police or sheriff action with respect to arrestees in their custody. Sincerely, Erwin Chemerinsky Dean University of California, Irvine, School of Law* Christopher Edley, Jr. Dean University of California, Berkeley, School of Law

19 Turning Migrants Into Criminals at 50. 20 Turning Migrants Into Criminals at 50.

*Affiliations listed for identification purposes only.

Governor Jerry Brown August 12, 2013 Page 10

Kevin Johnson Dean University of California, Davis, School of Law John Trasvina Dean University of San Francisco Frank H. Wu Chancellor & Dean University of California Hastings College of the Law Raquel E Aldana Professor of Law Director, Inter-American Program University of the Pacific McGeorge School of Law Farrin R. Anello Visiting Assistant Clinical Professor Seton Hall University School of Law Fran Ansley Distinguished Professor of Law Emeritus University of Tennessee College of Law Sameer M. Ashar Clinical Professor of Law University of California, Irvine, School of Law Gary Blasi Professor of Law Emeritus University of California, Los Angeles, School of Law Richard Boswell Professor of Law Associate Academic Dean for Global Programs University of California Hastings College of the Law Timothy Casey Visiting Professor California Western School of Law

Governor Jerry Brown August 12, 2013 Page 11

Christine N. Cimini Professor of Law Vermont Law School Marjorie Cohn Professor of Law Thomas Jefferson School of Law Holly S. Cooper Associate Director Immigration Law Clinic University of California, Davis, School of Law Allison Davenport Lecturer and Clinical Instructor International Human Rights Law Clinic University of California, Berkeley, School of Law Ingrid V. Eagly Assistant Professor of Law University of California, Los Angeles, School of Law Maria Echaveste Policy and Program Development Director The Chief Justice Earl Warren Institute on Law & Social Policy University of California, Berkeley, School of Law Richard H. Frankel Associate Professor of Law Director, Appellate Litigation Clinic Earle Mack School of Law, Drexel University Bill Ong Hing Professor of Law University of San Francisco Raha Jorjani Supervising Attorney and Lecturer Immigration Law Clinic University of California, Davis, School of Law

Governor Jerry Brown August 12, 2013 Page 12

Anil Kalhan Associate Professor of Law Earle Mack School of Law, Drexel University Liz Keyes Assistant Professor and Director Immigrant Rights Clinic University of Baltimore School of Law Kathleen Kim Professor of Law Loyola Law School Los Angeles Jennifer Lee Koh Associate Professor of Law Director, Immigration Clinic Western State College of Law Aarti Kohli Director of Immigration Policy The Chief Justice Earl Warren Institute on Law & Social Policy University of California, Berkeley, School of Law Alex Kreit Associate Professor Thomas Jefferson School of Law Annie Lai Assistant Clinical Professor University of California, Irvine, School of Law Brian K. Landsberg Distinguished Professor of Law Pacific McGeorge School of Law Kevin Lapp Associate Professor of Law Loyola Law School, Los Angeles Christopher N. Lasch Assistant Professor University of Denver Sturm College of Law

Governor Jerry Brown August 12, 2013 Page 13

Stephen Lee Assistant Professor of Law University of California, Irvine, School of Law Peter L. Markowitz Clinical Associate Professor of Law Director, Kathryn O. Greenberg Immigration Justice Clinic Cardozo School of Law Hiroshi Motomura Susan Westerberg Prager Professor of Law University of California, Los Angeles, School of Law Karen Musalo Professor of Law Director, Center for Gender and Refugee Studies University of California Hastings College of the Law Millard Murphy Lecturer Prison Law Clinic University of California, Davis, School of Law Maria Linda Ontiveros Professor of Law University of San Francisco Amagda Prez Executive Director, California Legal Rural Assistance Foundation, Inc. Lecturer University of California, Davis, School of Law Victor C. Romero Professor of Law Maureen B. Cavanaugh Distinguished Faculty Scholar The Pennsylvania State University, Dickinson School of Law Mark Rosenbaum Harvey J. Gunderson Professor from Practice Public Interest/Public Service Faculty Fellow Lecturer The University of Michigan Law School

Governor Jerry Brown August 12, 2013 Page 14

Leticia M. Saucedo Professor of Law Director of Clinic Legal Education University of California, Davis, School of Law James Frank Smith Professor of Law Emeritus University of California, Davis, School of Law

Dan R. Smulian Associate Professor of Clinical Law Safe Harbor Project BLS Legal Services Corporation Brooklyn Law School Jayashri Srikantiah Professor of Law Director, Immigrants' Rights Clinic Stanford Law School Juliet P. Stumpf Professor of Law Lewis & Clark Law School Linda Tam Director, Immigration Clinic East Bay Community Law Center Lecturer University of California, Berkeley, School of Law Enid Trucios-Haynes Professor of Law Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville Diane K. Uchimiya Professor of Law Justice and Immigration Clinic University of La Verne College of Law Tania N. Valdez Staff Attorney, Immigration Clinic

Governor Jerry Brown August 12, 2013 Page 15

East Bay Community Law Center Clinic Instructor University of California, Berekely, School of Law Leti Volpp Robert D. and Leslie-Kay Raven Professor of Law University of California, Berkeley, School of Law Bryan H. Wildenthal Professor Thomas Jefferson School of Law Michael J. Wishnie William O. Douglas Clinical Professor of Law Deputy Dean for Experiential Education Yale Law School

You might also like

- Arpaio - Attorney General Holder 01-16-2014Document6 pagesArpaio - Attorney General Holder 01-16-2014taraholiverNo ratings yet

- Gang of Eight Immigration ProposalDocument844 pagesGang of Eight Immigration ProposalThe Washington PostNo ratings yet

- Cuban Religious Leaders Call For Stop To DeportationsDocument4 pagesCuban Religious Leaders Call For Stop To DeportationsBjustb LoeweNo ratings yet

- #Not1More Blue Ribbon Commission SummaryDocument7 pages#Not1More Blue Ribbon Commission SummaryBjustb LoeweNo ratings yet

- Chicago For The People 2014 Freedom BallotDocument4 pagesChicago For The People 2014 Freedom BallotBjustb LoeweNo ratings yet

- Nayelly Letter To ObamaDocument10 pagesNayelly Letter To ObamaBjustb LoeweNo ratings yet

- Insecure Communities: Latino Perception of Police Involvement in Immigration EnforcementDocument28 pagesInsecure Communities: Latino Perception of Police Involvement in Immigration EnforcementBjustb LoeweNo ratings yet

- Municipal Resolution For CIR and Holds ExplorationDocument3 pagesMunicipal Resolution For CIR and Holds ExplorationBjustb LoeweNo ratings yet

- Deportation LetterDocument4 pagesDeportation LetterLas Vegas Review-JournalNo ratings yet

- White House Draft Proposal For Worksite EnforcementDocument95 pagesWhite House Draft Proposal For Worksite EnforcementBjustb LoeweNo ratings yet

- White House Draft Proposal For Border SecurityDocument75 pagesWhite House Draft Proposal For Border SecurityBjustb LoeweNo ratings yet

- 2012 08 Trust2Document11 pages2012 08 Trust2Bjustb LoeweNo ratings yet

- Leaked White House Comprehensive Immigration Reform BillDocument45 pagesLeaked White House Comprehensive Immigration Reform BillDreamACTivistNo ratings yet

- Memo On Alternatives To Comprehensive Immigration ReformDocument11 pagesMemo On Alternatives To Comprehensive Immigration Reformmatthew_libassi100% (1)

- Suit Against LA Sheriff's Dept For Unconstitutional ICE HoldsDocument48 pagesSuit Against LA Sheriff's Dept For Unconstitutional ICE HoldsBjustb LoeweNo ratings yet

- Municipal Resolution For CIRDocument2 pagesMunicipal Resolution For CIRBjustb LoeweNo ratings yet

- Briefing Guide Re: ICE QuotaDocument3 pagesBriefing Guide Re: ICE QuotaBjustb LoeweNo ratings yet

- John Morton's Sympathy Letter To Hate GroupDocument3 pagesJohn Morton's Sympathy Letter To Hate GroupBjustb LoeweNo ratings yet

- Rev. Jesse Jackson: The Moral Obligation To Sign The TRUST ActDocument1 pageRev. Jesse Jackson: The Moral Obligation To Sign The TRUST ActBjustb LoeweNo ratings yet

- All in One Guide To Defeating ICE HoldsDocument47 pagesAll in One Guide To Defeating ICE HoldsBjustb Loewe100% (1)

- Washington, DC Bright Line OrdinanceDocument3 pagesWashington, DC Bright Line OrdinanceBjustb LoeweNo ratings yet

- The Cost of Responding To Immigration Detainers in CaliforniaDocument4 pagesThe Cost of Responding To Immigration Detainers in CaliforniaSouthern California Public RadioNo ratings yet

- DHS Inspector General: Communications Regarding Secure CommunitiesDocument36 pagesDHS Inspector General: Communications Regarding Secure CommunitiesBjustb LoeweNo ratings yet

- DHS Inspector General Report: Operations of Secure CommunitiesDocument25 pagesDHS Inspector General Report: Operations of Secure CommunitiesBjustb LoeweNo ratings yet

- Order Granting Plaintiffs' Renewed Motion For Preliminary InjunctionDocument13 pagesOrder Granting Plaintiffs' Renewed Motion For Preliminary InjunctionRespect RespetoNo ratings yet

- In Hostile Terrain: A Human Rights Report On US Immigration Enforcement by Amnesty InternationalDocument88 pagesIn Hostile Terrain: A Human Rights Report On US Immigration Enforcement by Amnesty InternationalBjustb Loewe0% (1)

- Unregulated Work in Chicago: Breakdown of Workplace ProtectionsDocument72 pagesUnregulated Work in Chicago: Breakdown of Workplace ProtectionsBjustb LoeweNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Ruling On Comité de Jornaleros V Redondo BeachDocument47 pagesSupreme Court Ruling On Comité de Jornaleros V Redondo BeachBjustb LoeweNo ratings yet

- Programa Por La 6to Asamblea Nacional de NDLONDocument44 pagesPrograma Por La 6to Asamblea Nacional de NDLONBjustb LoeweNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Class Moot 1Document6 pagesClass Moot 1jodhani.ashok50No ratings yet

- Assignment Insurance LawDocument5 pagesAssignment Insurance LawJetheo100% (1)

- Important Notes: EconomyDocument2 pagesImportant Notes: Economydodi_auliaNo ratings yet

- Data Tugas Kelas 71 Mapel PrakaryaDocument8 pagesData Tugas Kelas 71 Mapel PrakaryaAndriana ManullangNo ratings yet

- Sex SlaveDocument5 pagesSex SlaveSolpeter_4No ratings yet

- Boardingpass Vistara MR S Das & MR S K OjhaDocument2 pagesBoardingpass Vistara MR S Das & MR S K OjhasuvadipNo ratings yet

- Suffrage (Art. V)Document10 pagesSuffrage (Art. V)alfieNo ratings yet

- Pictorial Travelogue West GermanyDocument67 pagesPictorial Travelogue West GermanyMaqsood A. KhanNo ratings yet

- Labour Law ProjectDocument16 pagesLabour Law Projectprithvi yadavNo ratings yet

- Refund p20Document12 pagesRefund p20srikant sawreNo ratings yet

- Contract Agreement Between HRL and SJ - SMEC - EGC 15 March 2021Document31 pagesContract Agreement Between HRL and SJ - SMEC - EGC 15 March 2021Arshad MahmoodNo ratings yet

- Restitution of Conjugal Rights Section 9Document10 pagesRestitution of Conjugal Rights Section 9Vishal Chaurasia (Vish)No ratings yet

- 47 BPI Vs CarreonDocument11 pages47 BPI Vs CarreondavidNo ratings yet

- MR Yang Ms ZhouDocument4 pagesMR Yang Ms ZhouOsama YaghiNo ratings yet

- Kalevi Holsti The State War and The State of War Select PagesDocument24 pagesKalevi Holsti The State War and The State of War Select PagesLuis JimenezNo ratings yet

- Interlocking DirectorsDocument3 pagesInterlocking DirectorsJan Aldrin AfosNo ratings yet

- Speech by Singapore PM, MR. LEE KUAN YEW, 27 May 1965Document20 pagesSpeech by Singapore PM, MR. LEE KUAN YEW, 27 May 1965SweetCharity77No ratings yet

- How To Plant ChurchesDocument9 pagesHow To Plant ChurchesJack BrownNo ratings yet

- Train TimingDocument44 pagesTrain TimingAli AdilNo ratings yet

- Naval Postgraduate School: Mba Professional ReportDocument91 pagesNaval Postgraduate School: Mba Professional Reporthe linNo ratings yet

- 3Document5 pages3Raaima AliNo ratings yet

- Personnel Security Management Office For IndustryPreviously Denied Clearance PG 1 PDF Embed 1Document1 pagePersonnel Security Management Office For IndustryPreviously Denied Clearance PG 1 PDF Embed 1Michael RothNo ratings yet

- Critique PaperDocument3 pagesCritique Paperara100% (4)

- Aim-120 Amraam: Advanced Medium Range Air-to-Air MissileDocument10 pagesAim-120 Amraam: Advanced Medium Range Air-to-Air MissileA RozzNo ratings yet

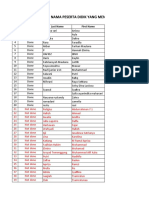

- Daftar Nilai Pat Pengetahuan Siswa Sekolah Dasar Islam Terpadu (Sdit) Nurul Ilmi TAHUN PELAJARAN 2018/2019Document36 pagesDaftar Nilai Pat Pengetahuan Siswa Sekolah Dasar Islam Terpadu (Sdit) Nurul Ilmi TAHUN PELAJARAN 2018/2019NurlailahNo ratings yet

- Vojni CinoviDocument1 pageVojni CinoviSanda MilićNo ratings yet

- Gcta Law 2019Document3 pagesGcta Law 2019DeniseNo ratings yet

- Order Form - H - E - 12th January - 2021Document11 pagesOrder Form - H - E - 12th January - 2021SanjeevNo ratings yet

- Apsa StyleDocument4 pagesApsa StyleLincoln DerNo ratings yet

- Final Adime Note AnemiacasestudyDocument2 pagesFinal Adime Note Anemiacasestudyapi-253526841No ratings yet